Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Renewable Energy Transition in Italy

1.2. Agrivoltaic as a Possible Solution to the Land-Energy Conflict

1.3. Agrivoltaic and Social Acceptance on Renewables

1.4. Land Eligibility as a Preliminary Analysis

1.5. The Urgent Need for Land Use Planning and Policy

1.6. Objectives of the Work

2. Materials and Methods

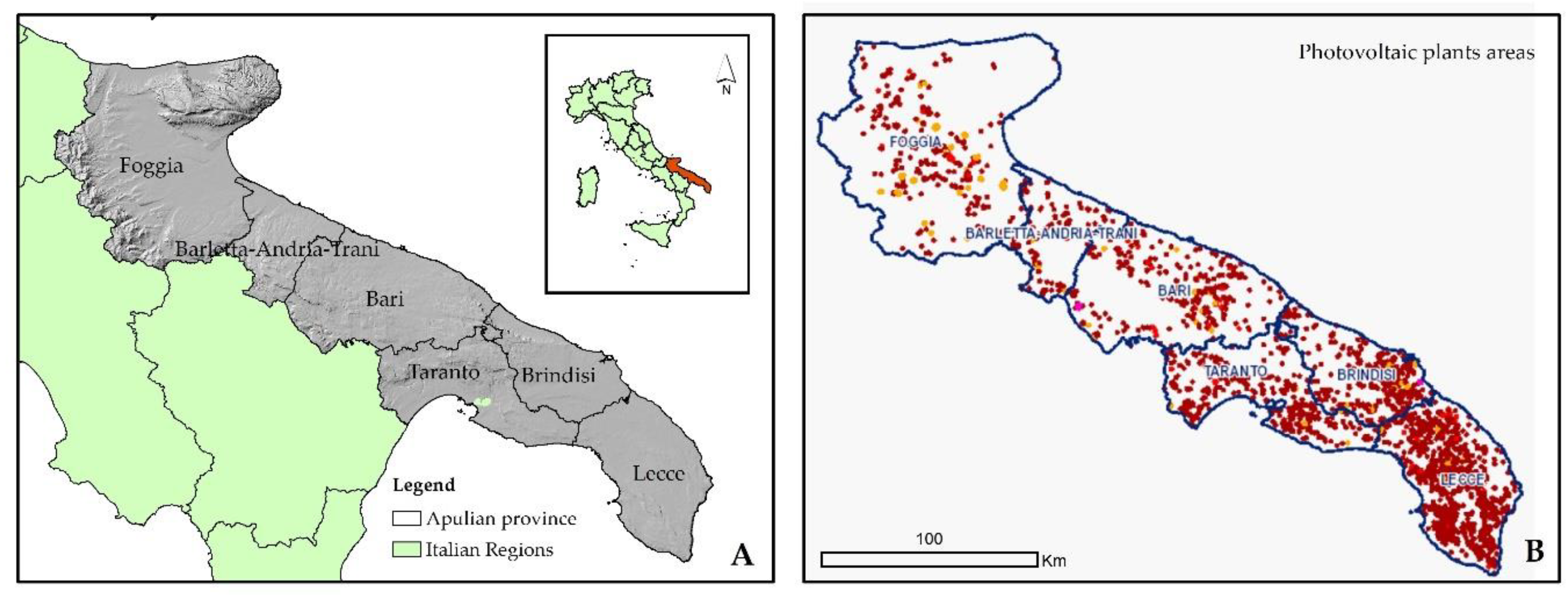

2.1. The Study Area

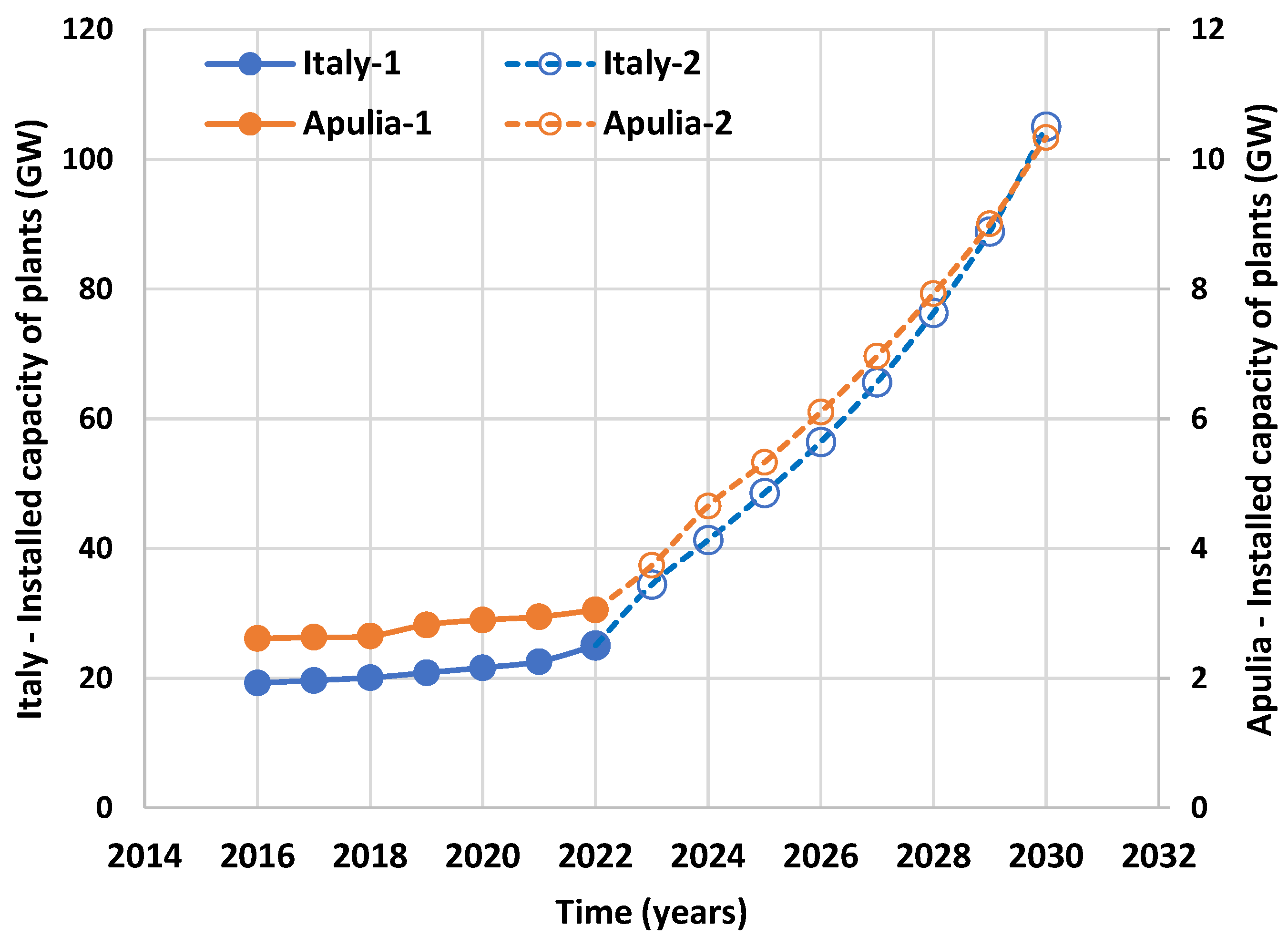

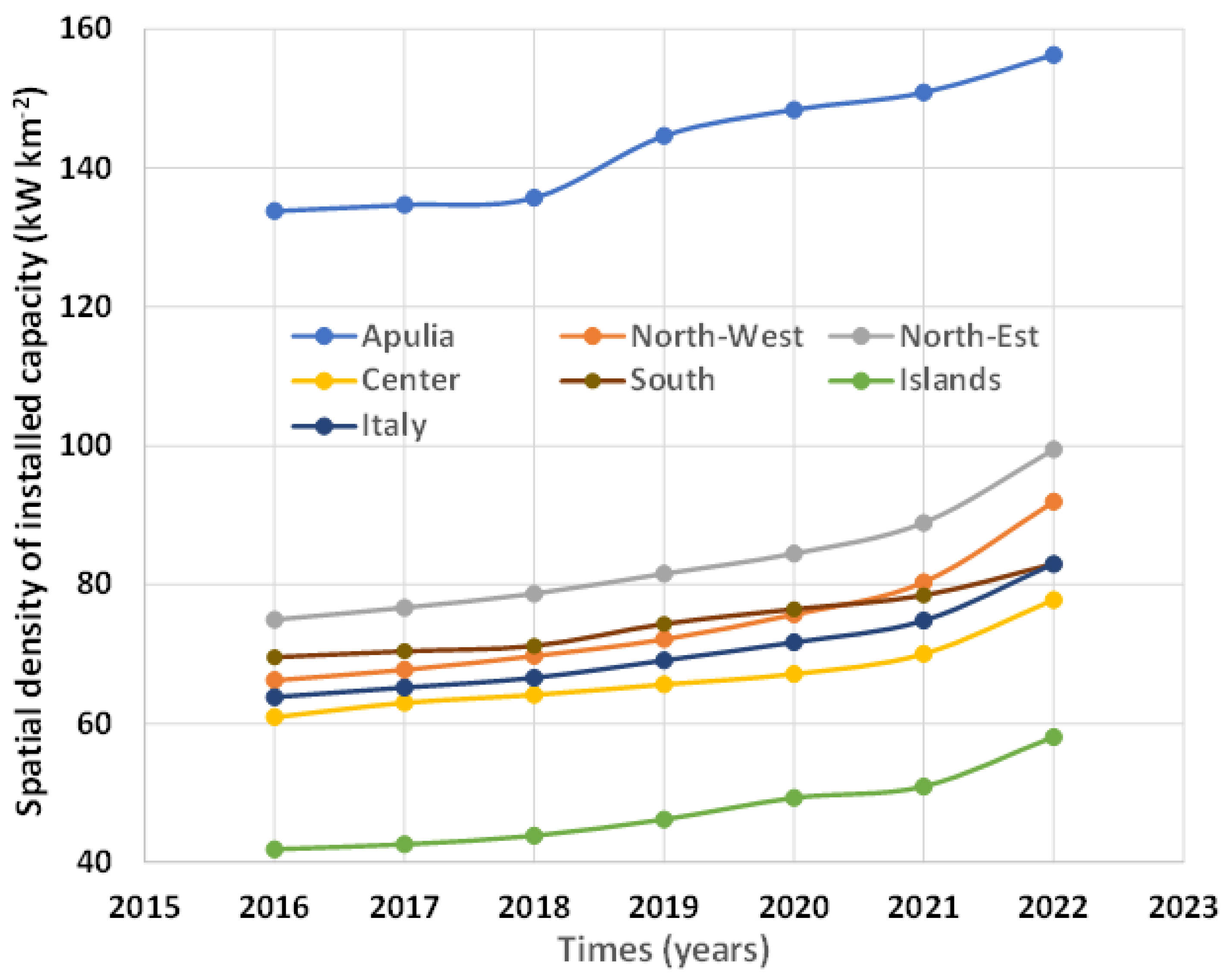

2.2. Past and Future of Solar Energy in the Apulia Region

2.3. The National and Regional Regulatory Framework on Renewable Energy Installations

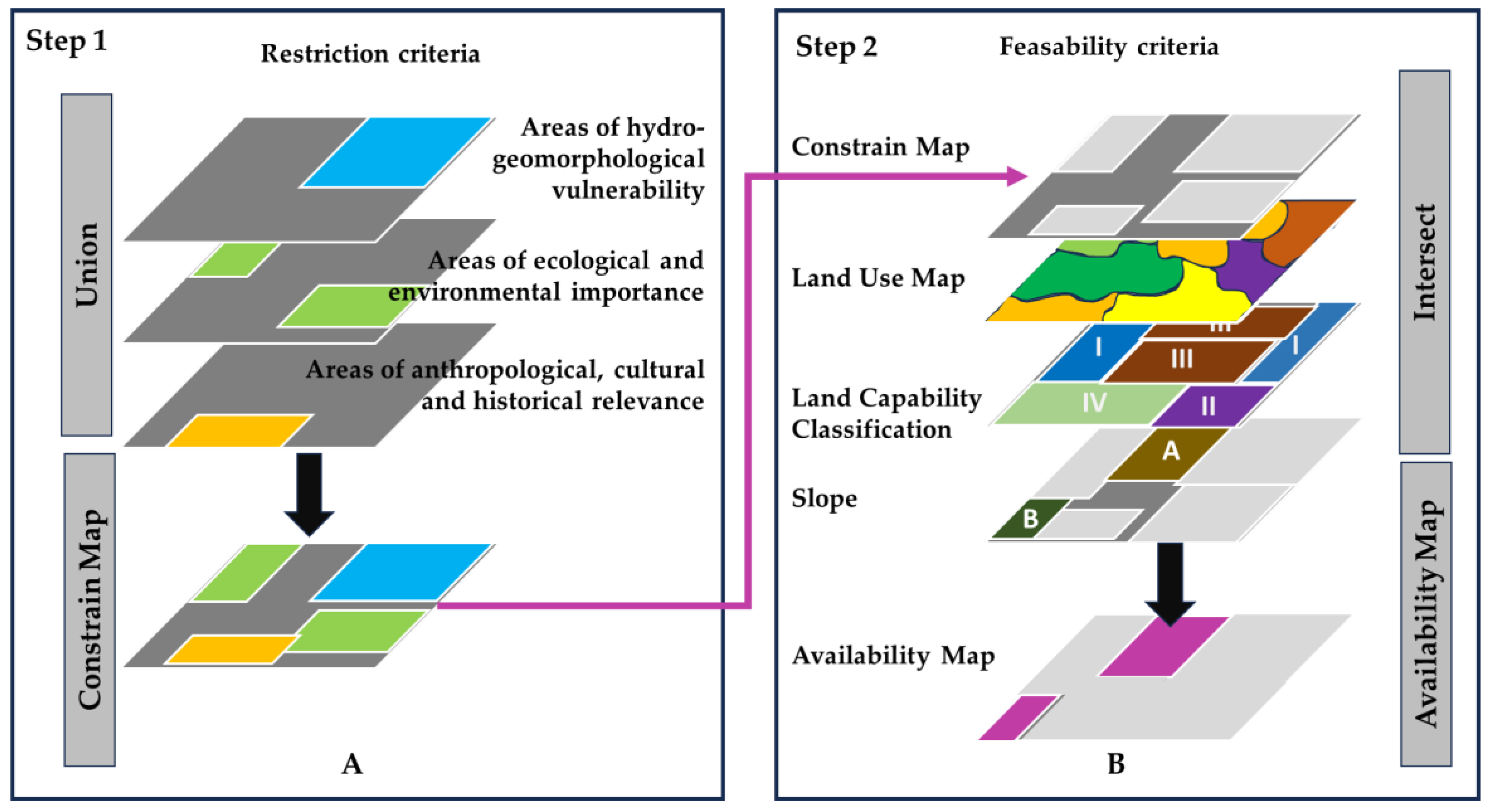

2.4. The Methodological Approach

2.4.1. Agricultural Land Use

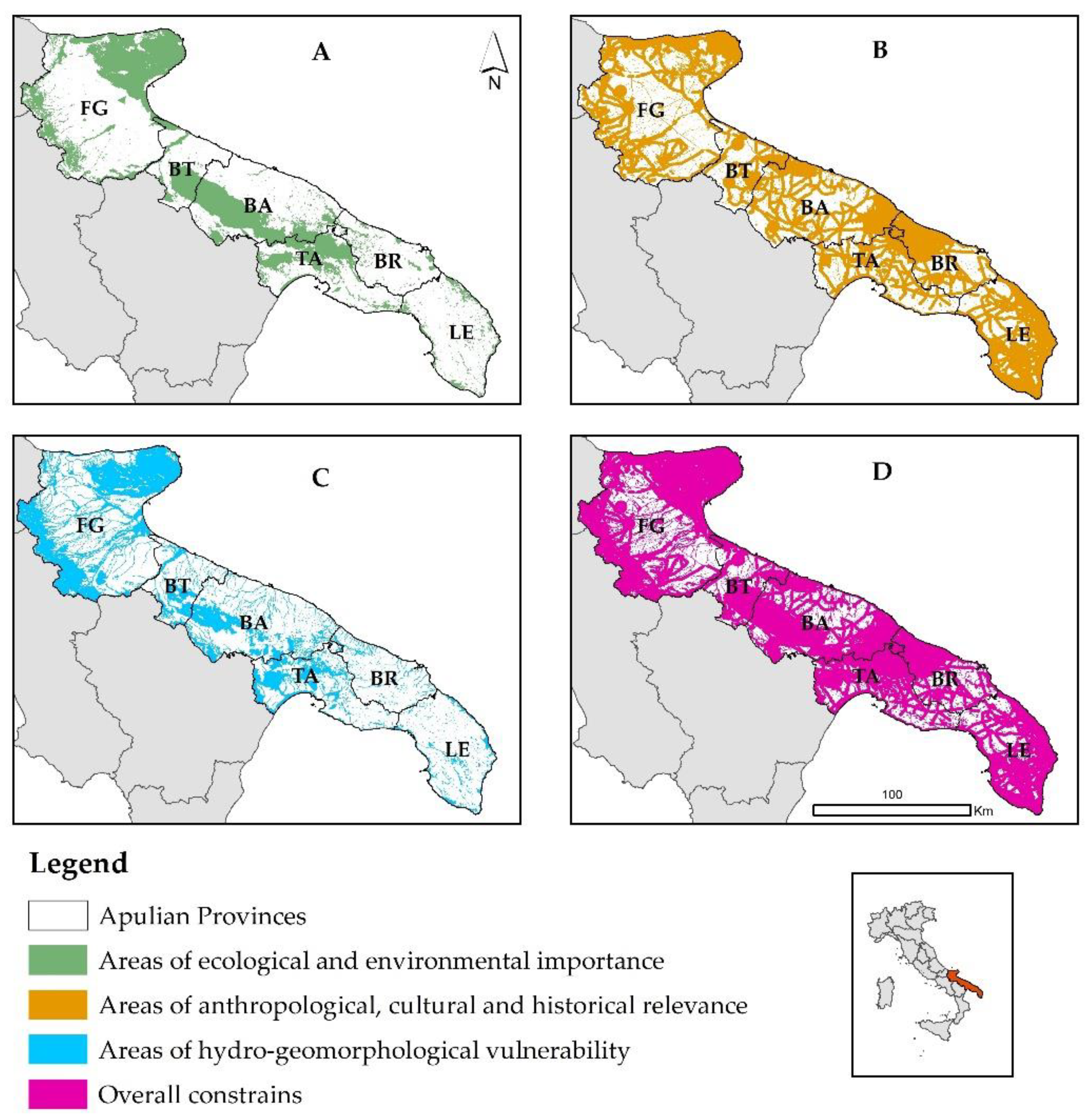

2.4.2. Restriction Criteria and Estimation of Available AV Agricultural Land

3. Results

3.1. Solar Energy Time Trend

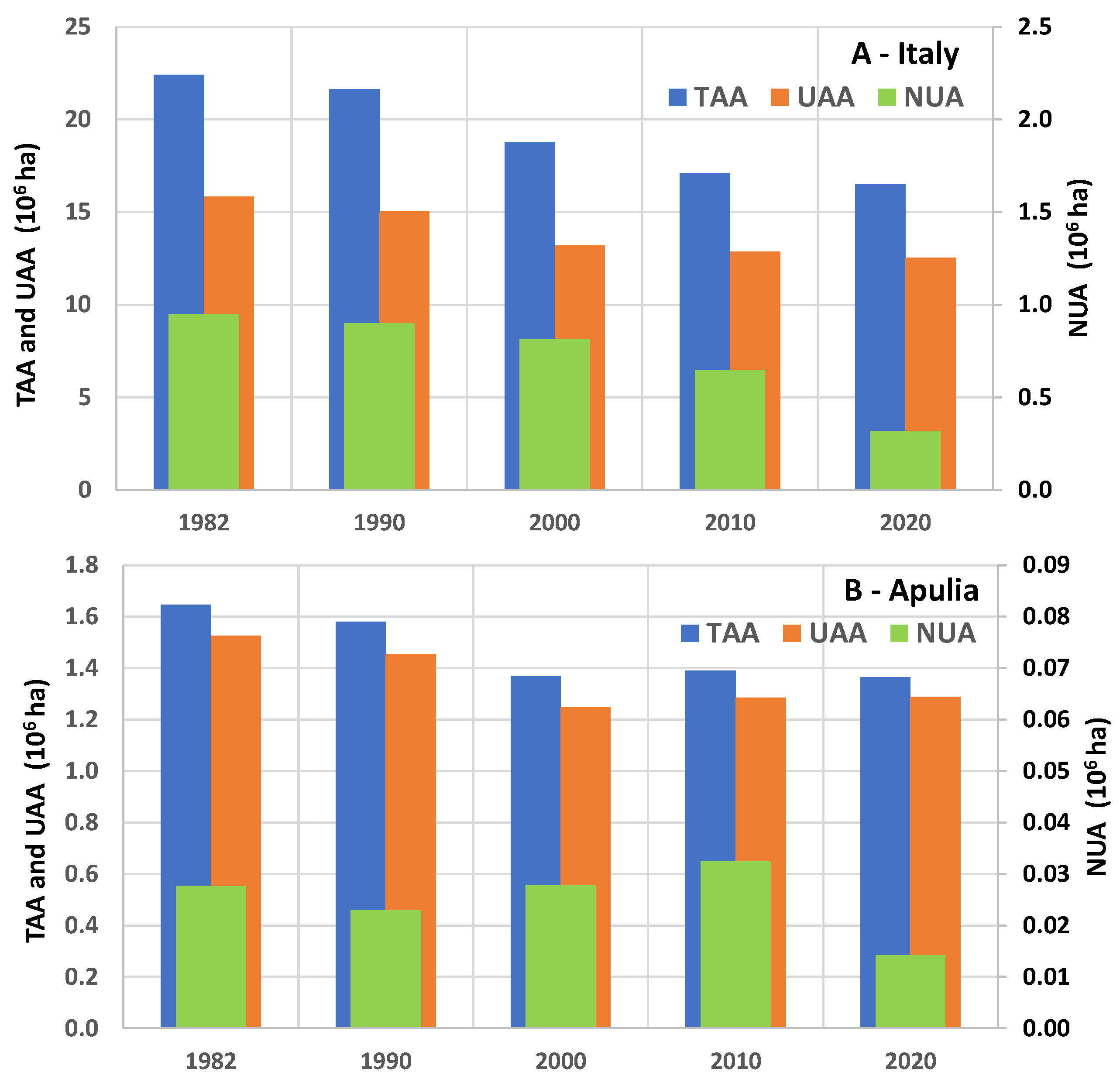

3.2. Agricultural Land Use

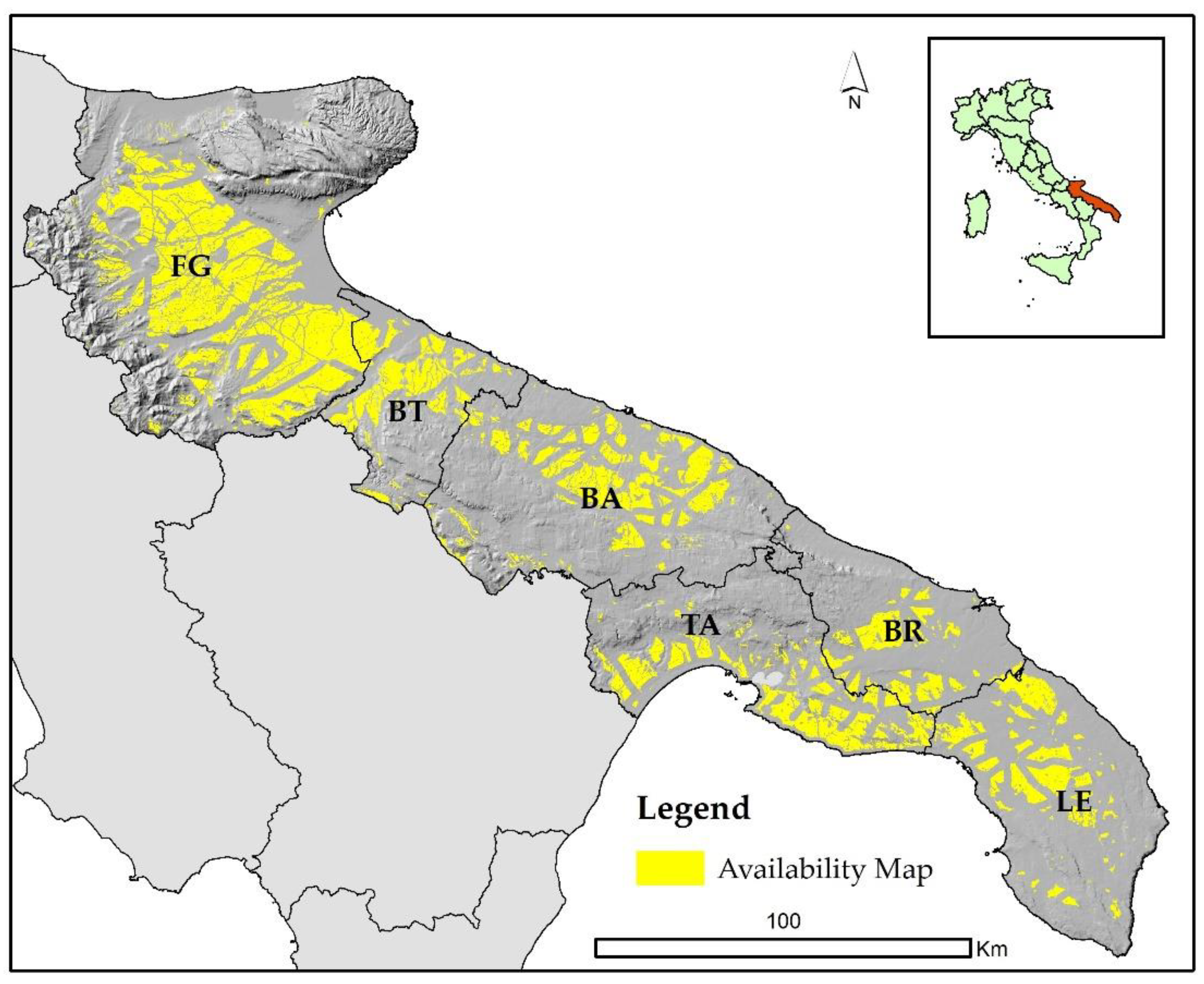

3.3. Estimation of Agricultural ‘Available Land’

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALP | Apulian Landscape Plan; |

| AV | Agrivoltaics; |

| GAEC | Good Agriculture and Ecological Condition |

| GIS | |

| Geographical Information System; | |

| HGP | Hydro-Geological Plan; |

| LCC | Land Capability Classification; |

| LUM | Land Use Map; |

| MASE | Italian Ministry for the Environment and Energy Security; |

| NECP | National Energy and Climate Plan; |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy; |

| PNRR | National Recovery and Resilience Plan; |

| PV | Photovoltaic; |

| RBA | River Basin Authority; |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources. |

References

- EU Council, 2023. Green Deal.

- Miller, C.A.; Iles, A.; Jones, C.F. The Social Dimensions of Energy Transitions. Science as Culture 2013, 22, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, M.J. Morality, Space, and the Power of Wind-Energy Landscapes. Geographical Review 2000, 90, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. What Are We Doing Here? Analyzing Fifteen Years of Energy Scholarship and Proposing a Social Science Research Agenda. Energy Research & Social Science 2014, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.S.; Lucas De Souza Silva, J.; Gomes Dos Reis, M.V.; De Bastos Mesquita, D.; Kikumoto De Paula, B.H.; Villalva, M.G. Experimental Comparative Study of Photovoltaic Models for Uniform and Partially Shading Conditions. Renewable Energy 2021, 164, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudes, D.; Van Den Brink, A.; Stremke, S. Towards a Typology of Solar Energy Landscapes: Mixed-Production, Nature Based and Landscape Inclusive Solar Power Transitions. Energy Research & Social Science 2022, 91, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketzer, D.; Schlyter, P.; Weinberger, N.; Rösch, C. Driving and Restraining Forces for the Implementation of the Agrophotovoltaics System Technology – A System Dynamics Analysis. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 270, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascaris, A.S.; Schelly, C.; Burnham, L.; Pearce, J.M. Integrating Solar Energy with Agriculture: Industry Perspectives on the Market, Community, and Socio-Political Dimensions of Agrivoltaics. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 75, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, R.; Fabrizio, E.; Garnero, G. The Territorial and Landscape Impacts of Photovoltaic Systems: Definition of Impacts and Assessment of the Glare Risk. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, A. ‘Photovoltaic Landscapes’: Design and Assessment. A Critical Review for a New Transdisciplinary Design Vision. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 55, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, V.; Bota, G.; Brotons, L.; Morán-Ordóñez, A. Addressing the Challenge of Photovoltaic Growth: Integrating Multiple Objectives towards Sustainable Green Energy Development. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission National Energy and Climate Plan 2023.

- SolarPower Europe (2023): Global Market Outlook for Solar Power 2023-2027.

- Chamber of Deputies - Italian Republic - Study Service, 2023. Public Policies on Renewa-Ble Energy Sources (in Italian).

- Industry – Chemistry, 2023. Alliance for Photovoltaics in Italy: “100 GW Needed for Energy Transition by 2030” (in Italian).

- IPCC, 2022. Factsheet Energy. Switzerland, Geneva.

- Macknick, J.; Hartmann, H.; Barron-Gafford, G.; Beatty, B.; Burton, R.; Seok-Choi, C.; Davis, M.; Davis, R.; Figueroa, J.; Garrett, A.; et al. The 5 Cs of Agrivoltaic Success Factors in the United States: Lessons from the InSPIRE Research Study; 2022; p. NREL/TP-6A20-83566, 1882930, MainId:84339.

- Goetzberger, A.; Zastrow, A. On the Coexistence of Solar-Energy Conversion and Plant Cultivation. International Journal of Solar Energy 1982, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, Y. Combining Solar Photovoltaic Panels and Food Crops for Optimising Land Use: Towards New Agrivoltaic Schemes. Renewable Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa’a, S.; Reher, T.; Rongé, J.; Diels, J.; Poortmans, J.; Radhakrishnan, H.S.; Van Der Heide, A.; Van De Poel, B.; Daenen, M. A Multidisciplinary View on Agrivoltaics: Future of Energy and Agriculture. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 200, 114515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaducci, S.; Yin, X.; Colauzzi, M. Agrivoltaic Systems to Optimise Land Use for Electric Energy Production. Applied Energy 2018, 220, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics Provide Mutual Benefits across the Food–Energy–Water Nexus in Drylands. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane Bhandari, S.; Schlüter, S.; Kuckshinrichs, W.; Schlör, H.; Adamou, R.; Bhandari, R. Economic Feasibility of Agrivoltaic Systems in Food-Energy Nexus Context: Modelling and a Case Study in Niger. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindele, S.; Trommsdorff, M.; Schlaak, A.; Obergfell, T.; Bopp, G.; Reise, C.; Braun, C.; Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Högy, P.; et al. Implementation of Agrophotovoltaics: Techno-Economic Analysis of the Price-Performance Ratio and Its Policy Implications. Applied Energy 2020, 265, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin; Shafiullah, G.M.; Ferdous, S.M.; Shoeb, M.; Reza, S.M.S.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Rahman, M.M. Agrivoltaics System for Sustainable Agriculture and Green Energy in Bangladesh. Applied Energy 2024, 371, 123709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; Bousi, E.; Özdemir, Ö.E.; Trommsdorff, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Anand, A.; Kant, K.; Chopra, S.S. Progress and Challenges of Crop Production and Electricity Generation in Agrivoltaic Systems Using Semi-Transparent Photovoltaic Technology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 158, 112126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walston, L.J.; Barley, T.; Bhandari, I.; Campbell, B.; McCall, J.; Hartmann, H.M.; Dolezal, A.G. Opportunities for Agrivoltaic Systems to Achieve Synergistic Food-Energy-Environmental Needs and Address Sustainability Goals. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 932018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enserink, M.; Van Etteger, R.; Van Den Brink, A.; Stremke, S. To Support or Oppose Renewable Energy Projects? A Systematic Literature Review on the Factors Influencing Landscape Design and Social Acceptance. Energy Research & Social Science 2022, 91, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddis, P.; Roelich, K.; Tran, K.; Carver, S.; Dallimer, M.; Ziv, G. What Shapes Community Acceptance of Large-Scale Solar Farms? A Case Study of the UK’s First ‘Nationally Significant’ Solar Farm. Solar Energy 2020, 209, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, C.; Scognamiglio, A. Agrivoltaic Systems Design and Assessment: A Critical Review, and a Descriptive Model towards a Sustainable Landscape Vision (Three-Dimensional Agrivoltaic Patterns). Sustainability 2021, 13, 6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Bühner, C.; Gölz, S.; Trommsdorff, M.; Jürkenbeck, K. Factors Influencing the Willingness to Use Agrivoltaics: A Quantitative Study among German Farmers. Applied Energy 2024, 361, 122934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Moon, H.-W.; Kim, Y.H.; Ku, K.-M. Agrivoltaic Systems Enhance Farmers’ Profits through Broccoli Visual Quality and Electricity Production without Dramatic Changes in Yield, Antioxidant Capacity, and Glucosinolates. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Hernández, A.S.; Ramos De Arruda, L.V. Technical–Economic Potential of Agrivoltaic for the Production of Clean Energy and Industrial Cassava in the Colombian Intertropical Zone. Environmental Quality Mgmt 2022, 31, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpanalaisatit, M.; Setthapun, W.; Sintuya, H.; Pattiya, A.; Jansri, S.N. Current Status of Agrivoltaic Systems and Their Benefits to Energy, Food, Environment, Economy, and Society. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 33, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, H.; Ogata, S. Integrating Agrivoltaic Systems into Local Industries: A Case Study and Economic Analysis of Rural Japan. Agronomy 2023, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Bonnington, A.; Pearce, J.M. The Agrivoltaic Potential of Canada. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkadeem, M.R.; Zainali, S.; Lu, S.M.; Younes, A.; Abido, M.A.; Amaducci, S.; Croci, M.; Zhang, J.; Landelius, T.; Stridh, B.; et al. Agrivoltaic Systems Potentials in Sweden: A Geospatial-Assisted Multi-Criteria Analysis. Applied Energy 2024, 356, 122108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri Nugroho, A.; Pramono Hadi, S.; Sutanta, H.; Adikara Ajrin, H. Optimising Agrivoltaic Systems: Identifying Suitable Solar Development Sites for Integrated Food and Energy Production. PEC 2024, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattoruso, G.; Toscano, D.; Venturo, A.; Scognamiglio, A.; Fabricino, M.; Di Francia, G. A Spatial Multicriteria Analysis for a Regional Assessment of Eligible Areas for Sustainable Agrivoltaic Systems in Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reher, T.; Lavaert, C.; Ottoy, S.; Martens, J.A.; Van Orshoven, J.; Cappelle, J.; Diels, J.; Van De Poel, B. Room for Renewables: A GIS-Based Agrivoltaics Site Suitability Analysis in Urbanized Landscapes. Agricultural Systems 2025, 224, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, S.; Elçin Günay, E.; Kula, U.; Kremer, G.E. Assessing Agrivoltaics Potential in Türkiye – A Geographical Information System (GIS)-Based Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024, 197, 110598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Overview of the Potential and Challenges for Agri-Photovoltaics in the European Union.; Publications Office: LU, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Federazione A. Sistemi Agro-Fotovoltaica. 2022.

- Renewable Energies and European Landscapes: Lessons from Southern European Cases; Frolova, M., Prados, M.-J., Nadaï, A., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2015; ISBN 978-94-017-9842-6. [Google Scholar]

- Impianti FER DGR 2122. Https://Webapps.Sit.Puglia.It/Freewebapps/ImpiantiFERDGR2122/.

- GSE Rapporto Statistico Solare-Fotovoltaico. Il Solare Fotovoltaico in Italia. Stato Di Sviluppo e Trend Del Settore 2022.

- https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2024/07/13/163/sg/pdf DL 12 Luglio 2024, n. 101 - Disposizioni Urgenti per Le Imprese Agricole, Della Pesca e Dell’acquacoltura, Nonché per Le Imprese Di Interesse Strategico Nazionale.

- https://www.istat.it/notizia/censimento-agricoltura-2020-online-i-principali-dati/ ISTAT, 2020. Censimento Agricoltura.

- Apulian Land Use Map 2011.

- Land Capability Classification, Apulia Region.

- Viviani, N.; Wijaksono, S.; Mariana, Y. Solar Radiation on Photovoltaics Panel Arranging Angles and Orientation. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 794, 012230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogno Mondino, E.; Fabrizio, E.; Chiabrando, R. Site Selection of Large Ground-Mounted Photovoltaic Plants: A GIS Decision Support System and an Application to Italy. International Journal of Green Energy 2015, 12, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Santa, R.; Crnac, Z.; Bošnjaković, T. Environmental Impact of PV Power Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA Efficiency and Decarbonization Indicators in Italy and in the Biggest European Countries 2024.

- Energy & Strategy Group, Politecnico di Milano. Renewable Energy Report. Gli Scenari Future Delle Rinnovabili in Italia (Future Scenarios for Renewables in Italy). 2019.

- Italian Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security. Guidelines in the Field of Agrivoltaic Systems. 2023.

- European Standards. DIN SPEC 91434. Agri-Photovoltaic Systems - Requirements for Primary Agricultural Use. 2023.

- L´egisfrance LAW N◦ 2023–175 of March 10, 2023 Relating to the Acceleration of the Production of Renewable Energies 2023.

- US Department of Energy Market Research Study. Agrivoltaics. 2022.

- Gonocruz, R.A.; Uchiyama, S.; Yoshida, Y. Modeling of Large-Scale Integration of Agrivoltaic Systems: Impact on the Japanese Power Grid. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 363, 132545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI/PdR 148:2023. Sistemi Agrivoltaici - Integrazione Di Attivit`a Agricole e Impianti Fotovoltaici. 2023.

- Torma, G.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Social Acceptance of Dual Land Use Approaches: Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Drivers and Barriers Confronting Agrivoltaics Diffusion. Journal of Rural Studies 2023, 97, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchelli, S.; Garegnani, G.; Geri, F.; Grilli, G.; Paletto, A.; Zambelli, P.; Ciolli, M.; Vettorato, D. Trade-off between Photovoltaic Systems Installation and Agricultural Practices on Arable Lands: An Environmental and Socio-Economic Impact Analysis for Italy. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Nguyen, J.; Pearce, J.M. Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Agrivoltaic Produce: The Mediating Role of Trust. SSRN Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketzer, D.; Weinberger, N.; Rösch, C.; Seitz, S.B. Land Use Conflicts between Biomass and Power Production – Citizens’ Participation in the Technology Development of Agrophotovoltaics. Journal of Responsible Innovation 2020, 7, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protection criteria and constraints | Description |

|---|---|

| a) Areas of ecological and environmental importance1 | (1) |

| Botanical and Vegetational components | Woods + 100 m buffer; Natural pastures, Shrublands, Wetlands. |

| Protected areas and naturalistic sites | Natural parks + 100 m buffer, Other sites of naturalistic interest. |

| b) Areas of anthropological, cultural and historical relevance 1 | (1) |

| Cultural and settlements components | Historical and cultural sites + buffer of 100 m; relevant rural landscapes; areas of archeological interest + 100 m buffer; sheep tracks network + 100 m buffer. |

| Landscape components | Scenic roads + 1 km buffer; view cones; scenic places + 1 km buffer. |

| c.1) Areas of hydro-geomorphological vulnerability 1 | (1) |

| Geomorphological components | Slopes greater than 20 %; blades and ravines; dolines; caves + 100 m buffer, geosites + 100 m buffer; sinkholes + 50 m buffer; dune belts. |

| Hydrogeological components | Coastal territories + 300 m buffer; territories contiguous to lakes + 300 m buffer; rivers, streams, watercourses + 100 m buffer; hydrographic network as a link to the ecological network + 100 m buffer; springs + 25 m buffer; areas of hydrogeological risk. |

| c.2) Areas of hydro-geomorphological vulnerability 2 | (2) |

| Hydrological hazard | - High hazard (HA): areas subject to flooding with a return period ≤ 30 years.- Medium Hazard (MH): areas subject to flooding with a return period between 30 and 200 years. |

| Geomorphological hazard | - High hazard (PG3): areas affected by active or quiescent landslide phenomena.- Medium hazard (PG2): areas characterized by the presence of two or more geomorphological factors predisposing the occurrence of slope instability and/or stabilized landslides. |

| Province | NUA | NUA/UAA | AV Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ha) | (%) | (GW) | |

| BA | 3,145 | 1.20 | 1.26 |

| BR | 1,593 | 1.32 | 0.64 |

| BT | 866 | 0.80 | 0.35 |

| FG | 4,154 | 0.82 | 1.66 |

| LE | 1,744 | 1.14 | 0.70 |

| TA | 2,678 | 1.79 | 1.07 |

| Total (Apulia) | 14,183 | 1.10 | 5.67 |

| Province | Terr. Area (ha) |

Area EE (ha) |

Area ACH (ha) |

Area HGM (ha) |

Constr. Area (ha) |

Constr. Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 382,478 | 134,040 | 223,251 | 107,839 | 292,025 | 76.35 |

| BR | 183,942 | 20,394 | 120,211 | 22,321 | 130,189 | 70.78 |

| BT | 153,003 | 51,258 | 77,431 | 46,624 | 108,001 | 70.59 |

| FG | 695,679 | 261,694 | 359,498 | 336,361 | 511,608 | 73.54 |

| LE | 276,230 | 34,937 | 210,048 | 37,193 | 217,430 | 78.71 |

| TA | 244,068 | 99,967 | 136,262 | 87,292 | 187,453 | 76.80 |

| Apulia | 1,935,400 | 602,290 | 1,126,701 | 637,630 | 1,446,706 | 74.75 |

| Province | A Terr. Area (ha) |

B LCC I-IV (ha) |

C LCC III-IV (ha) |

D B/A (%) |

E C/A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 382,478 | 290,095 | 213,153 | 75.85 | 55.73 |

| BR | 183,942 | 152,132 | 93,726 | 82.71 | 50.95 |

| BT | 153,003 | 117,374 | 94,470 | 76.71 | 61.74 |

| FG | 695,679 | 479,233 | 408,266 | 68.89 | 58.69 |

| LE | 276,230 | 204,449 | 152,844 | 74.01 | 55.33 |

| TA | 244,068 | 162,504 | 132,876 | 66.58 | 54.44 |

| Apulia | 1,935,400 | 1,405,788 | 1,095,334 | 72.64 | 56.59 |

| Province | FC.1 (ha) |

FC.2 within FC.1 (ha) |

FC.3 within FC.1 (ha) |

FC.2 or FC.3 within FC.1 (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 55,173 | 54,487 | 104 | 54,591 |

| BR | 24,725 | 24,725 | 0 | 24,725 |

| BT | 33,757 | 33,056 | 102 | 33,158 |

| FG | 162,741 | 159,342 | 736 | 160,078 |

| LE | 35,782 | 35,780 | 0 | 35,780 |

| TA | 42,087 | 41,982 | 33 | 42,015 |

| Apulia | 354,264 | 349,373 | 975 | 350,348 |

| Province | Terr. Area (ha) |

UAA (ha) |

Available area (ha) |

Avail/Terr. (%) |

Avail/UAA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 382,478 | 262,924 | 54,591 | 14.27 | 20.76 |

| BR | 183,942 | 121,098 | 24,725 | 13.44 | 20.42 |

| BT | 153,003 | 108,270 | 33,158 | 21.67 | 30.63 |

| FG | 695,679 | 505,337 | 160,078 | 23.01 | 31.68 |

| LE | 276,230 | 152,954 | 35,780 | 12.95 | 23.39 |

| TA | 244,068 | 149,542 | 42,015 | 17.21 | 28.10 |

| Apulia | 1,935,400 | 1,300,125 | 350,348 | 18.10 | 26.95 |

| Province | UAA (ha) |

Available area (ha) |

Lower Scenario Power Capacity (MW) |

Upper Scenario Power Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 262,924 | 54,591 | 526 | 1,052 |

| BR | 121,098 | 24,725 | 242 | 484 |

| BT | 108,270 | 33,158 | 217 | 433 |

| FG | 505,337 | 160,078 | 1,011 | 2,021 |

| LE | 152,954 | 35,780 | 306 | 612 |

| TA | 149,542 | 42,015 | 299 | 598 |

| Apulia | 1,300,125 | 350,348 | 2,600 | 5,201 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).