1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a severe symptomatic infection of the lower respiratory tract that occurs outside of a hospital [

1]. Antimicrobial therapy is the primary treatment option for CAP [

2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) report on antimicrobial resistance and surveillance and the antimicrobial resistance global action plan, , both attest to the growing attention that the issue of antibiotic resistance has received in recent years [

3,

4]. According to the WHO report, the issue poses a global health security concern and requires coordinated cross-sectional response from governments and society [

5]. Experts urge a rational approach to antibiotic therapy in light of increasing Anti-Microbial Resistance (AMR), which is a growing global concern [

6].

The rational use of antibiotics encompasses not only the activities of clinicians in ensuring patients receive adequate treatment for their disease, at the correct dose and duration, but also the actions of patients in following the treatment regimens provided and completing the entire course [

5]. In 2001, the WHO Global Strategy for antibiotic Resistance Containment stressed the significance of developing and implementing guidelines and treatment algorithms to promote effective antibiotic use, as well as clinical practice supervision and support (WHO, 2001). Additionally, it stressed that health care practitioners play a crucial role in educating patients about the significance of treatment adherence [

5].

Incomplete treatment regimens and the use of inferior antimicrobials are common consequences of fragmented health services and a lack of access to reasonably priced, high-quality medications [

8]. These circumstances also foster the development of resistant organisms [

9]. Irrational antimicrobial prescription practices are mostly caused by a complex interaction of circumstances, while inadequate knowledge on the part of providers and a lack of standard treatment recommendations are significant indicators [

8,

10]. Inappropriate prescription practices can be caused by inadequate health professional training and supervision, a lack of diagnostic facilities to support treatment decisions, incorrect pharmaceutical marketing, prescribing, and dispensing among other factors [

11]. On the other hand, the irrational use of antibiotics is encouraged by the lack of laws or guidelines governing the composition and use of these drugs as well as by the ineffective enforcement of existing laws and guidelines [

12].

Ndola Teaching Hospital (NTH) through the Anti-Microbial Stewardship (AMS) committee promotes the appropriate use of antibiotics through the development and application of treatment guidelines and educational efforts aimed at clinicians and patients. This should help curb inappropriate prescribing and misuse of antibiotics, decrease treatment costs, and increase patient satisfaction [

13].

1.2. Problem Statement and Justification

Information about the rational use of antibiotics in management of CAP is very scarce especially for major hospitals in Zambia. NTH has embarked on strengthening the AMS committee, which is tasked, among other responsibilities, to ensure rational use of anti-microbials.

Rational antibiotic prescribing, infection control procedures and laboratory confirmed diagnosis are all necessary for the prevention of AMR [

14]. On the other hand, irrational use of antibiotics can lead to the growth of drug-resistant bacteria and a decline in the quality of antimicrobials that are accessible for the treatment of infectious diseases [

11]. This approach may also lead to resource waste, particularly financial waste since more costly treatments must be used to treat the illnesses [

5].

Furthermore, the increased use of second and third-line medications like 3

rd generations cephalosporins and carbapenems, which are typically more costly and hazardous and raises the incidence of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) [

15].

Therefore, it was necessary to assess the rational use of antibiotics and inform on the best practices for appropriate antibiotic use in the hospital settings especially in the management of CAP. This study was also intended to help the NTH better understand the management of the disease and determine whether the guidelines were adhered to by evaluating the rational use of antibiotics in the management of CAP. Additionally, this research will also contribute to the rational prescription of antibiotics for the management of CAP in other hospitals and other similar settings, which have been experiencing similar challenges.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

CAP is a frequent infectious condition that causes a high risk of hospitalization [

12,

16]. It is defined as a sickness emerging from an acute infection, mainly bacterial, and is characterized by clinical and radiographic symptoms of consolidation of a section or parts of one or both lungs [

1].

2.2. Epidemiology

2.2.1. Burden

Pneumonia is the second most prevalent cause of life years lost, the most common infectious cause of death worldwide, and the fourth most common cause of death overall [

17]. In 2023, lower respiratory tract infections were responsible for 3 million deaths worldwide, highlighting their significant global impact. [

18]. Estimates indicate that 4 million cases of pneumonia and 200,000 deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa annually [

2]. In many of the region's countries, infections and respiratory illnesses are the most common causes of adult hospitalization [

19]. According to estimates, the yearly prevalence of LRTI in adults under 60 is 10 episodes per 1000, but it is much greater in the elderly and in people living with HIV [

17].

2.2.2. Risk Factors

The most common risk factors for CAP in high-income environments include advancing age, male sex, smoking, congestive heart failure, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes [

17]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the same physiological and comorbid risk factors are probably also connected with CAP, although the dangers associated with HIV or immunocompromised patients, infection are far greater [

20,

21]. Pneumonia in children has been traced back to exposure to household air pollution caused by domestic combustion of biomass fuels for cooking, lighting, and heating [

22]. The prevalence of pneumonia in the area may also be influenced by malnutrition and crowded households [

23]. Compared to settings with adequate resources, the majority of patients in CAP cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa are relatively young, working age individuals due to the combined influence of these risk factors [

2].

2.3. CAP Clinical Assessment

2.3.1. Diagnosis and Aetiology of CAP

Pneumonia can be mimicked by the clinical signs and symptoms of many diseases and syndromes. Careful assessment is necessary when there is a high likelihood of a differential diagnosis since incorrect diagnoses that are delayed can lead to worse results [

24]. The primary differential diagnosis for patients with mild community-acquired pneumonia is upper respiratory infection. Clinicians should rely on point-of-care diagnostics (such as C-reactive protein [CRP]) and clinical evaluations (such as focused chest sounds, exclusion of other potential diagnosis, and signs of LRTI) [

25].

Serious community-acquired pneumonia patients need to be closely watched for additional potentially fatal conditions. Antibiotic treatment should be started as soon as possible because it can be challenging to distinguish pneumonia from noninfectious conditions such as sudden heart failure [

26]. Antibiotic overuse can be prevented by using biomarkers, such as procalcitonin [PCT], which can aid in the early distinction from heart failure decompensation. Antibiotic therapy needs to be discontinued if pneumonia is ruled out [

27]. Underlying conditions such as lung cancer, metastases, Tuberculosis (TB), foreign bodies, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and unclear immunosuppressive status should be suspected in individuals with recurrent pneumonia [

28].

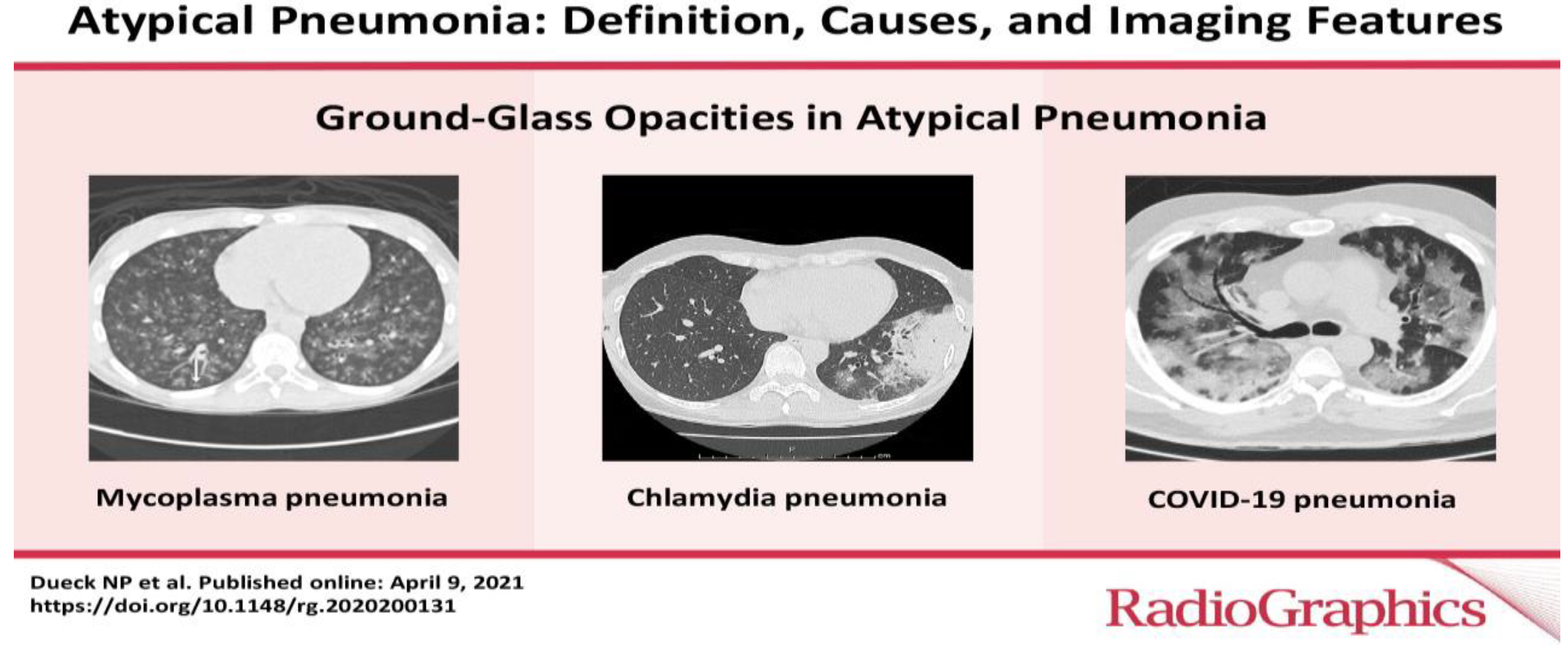

Clinically, CAP is frequently categorized as either atypical or typical. Bacterial infections such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus are responsible for typical pneumonia. Atypical CAP, on the other hand, is caused by a variety of pathogenic organisms, such as viruses, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophilia, Chlamydia psittaci, and Coxiella burnetli [

29]

–[

31]. In Western countries, nearly 60 - 80% of CAP are caused by bacteria, 10 - 20-% by atypical organisms and a similar proportion by viruses while in the sub-Saharan region 50 to 75% is typical while atypical accounts for less than 20% of the cases [

17,

32].

Figure 1.

Atypical Pneumonia: Definition, Causes and Imaging Features [

33].

Figure 1.

Atypical Pneumonia: Definition, Causes and Imaging Features [

33].

Figure 2.

Typical Pneumonia: Chest X-ray Imaging Features [

33].

Figure 2.

Typical Pneumonia: Chest X-ray Imaging Features [

33].

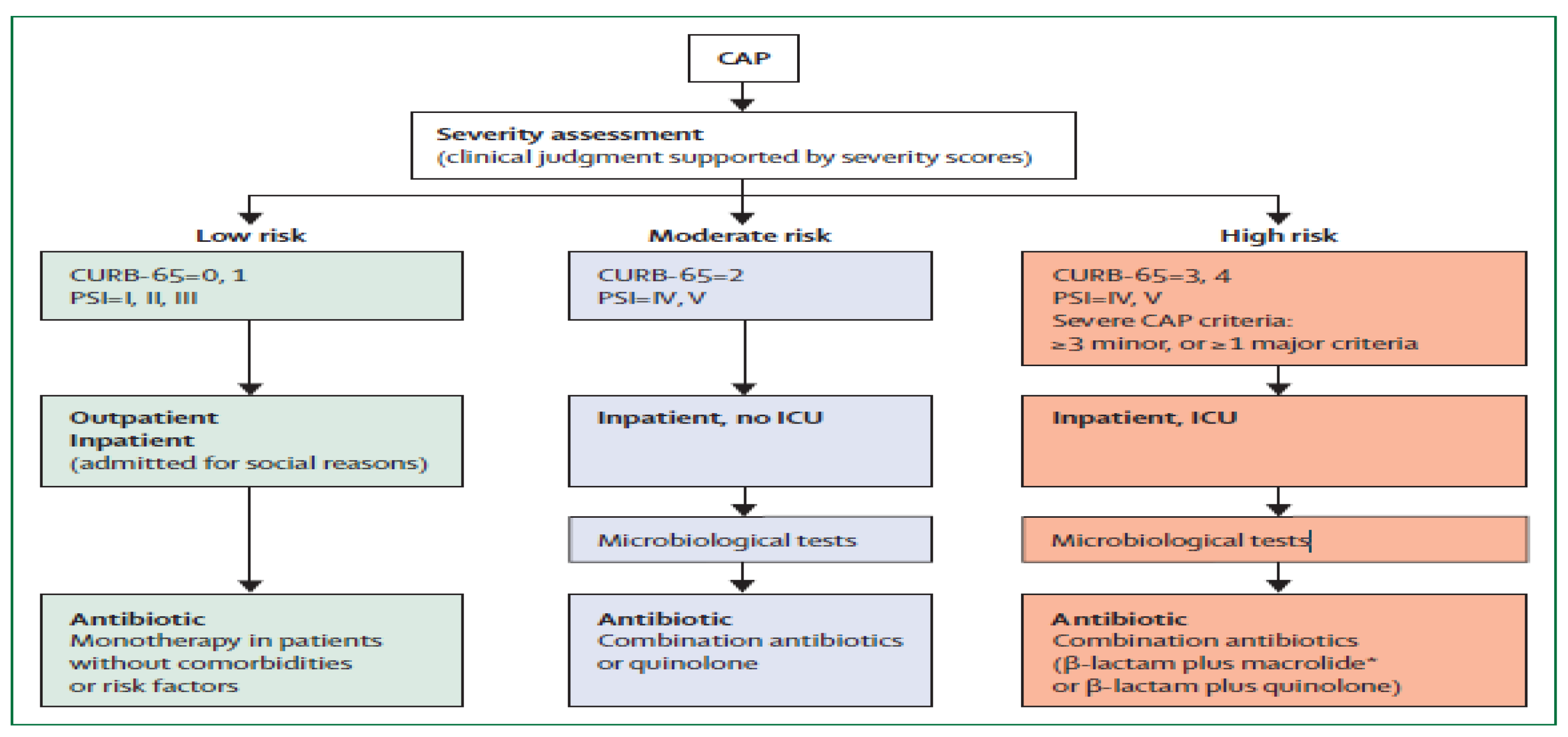

2.3.2. CAP Severity Assessment

In order to determine antibiotic therapy and care level, disease severity measures are used to predict mortality [

17]. A validated tool should be used to objectively assess the severity of the disease before making any early management decisions, such as selecting the antibiotic to use or the place of care [

2]. When determining the severity of a disease, the United States of America (USA) uses the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), but most European and African nations use algorithms based on Confusion, Urea, Blood Pressure, and Age ≥ 65 Years (CURB-65), or CRB-65, a condensed version of CURB-65 that doesn't require laboratory testing (like urea) [

17,

34].

To illustrate the utilization of severity tools; patients with low risk of mortality (CURB-65, 0-1) may be treated in outpatient setting, but if admitted to the hospital the Zambia Standard Treatment Guidelines recommends monotherapy [

35]. Patients with moderate risks (CURB-65, 2) may be potential candidates for hospitalization, the guidelines recommends combination of antibiotics while patients with high risk of mortality (CURB-65, 3-4) would require definite admission to high dependance units to be managed with a combination of antibiotics. [

34,

35].

Figure 3.

CAP Severity Assessment [

25].

Figure 3.

CAP Severity Assessment [

25].

2.4. Antimicrobial Therapy

2.4.1. General Considerations

Given the severity of the condition, the initial course of antibiotic therapy for CAP patients is nearly often empirical [

34]. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials are used in severe CAP to provide prompt protection against all likely infections [

36]. Some of them are Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Gram-negative intestinal bacteria [

11]. As a way to early rationalize treatment, extensive microbiological tests are encouraged [

15].

Although there is a great deal of diversity in the recommendations for the cover of typical and atypical organisms, mild disease is often treated in high-income nations with medicines with a limited scope [

17]. In the case of clinical failure, therapy is expanded using this method [

31]. There are challenges with implementing similar strategies in numerous sub-Saharan African contexts. The sub-Saharan region has a history of using antibiotics improperly to treat CAP, which can result in AMR [

24].

2.5. Literature Review Summary

Numerous studies have demonstrated a good correlation between adherence to guidelines and clinical outcomes, and irrational antibiotic prescribing in CAP has been linked to AMR (Kakkar et al., 2020; Masterton, 2011; WHO, 2017). Nevertheless, the majority of these studies are from other countries, and little is known regarding the appropriate use of antibiotics in managing CAP in Zambia.

3. Research Objective

3.1. Main Objective

To assess the rational use of antibiotics in the management of community acquired pneumonia at Ndola Teaching Hospital.

3.2. Specific Objectives

To determine if the severity of CAP is assessed using CURB-65 and documented in patient files

To evaluate the relationship between the length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality.

To assess the influence of age (above 65 years) on in-hospital mortality in the management of CAP.

To assess what proportion of prescribed antibiotics are supported by lab-confirmed results.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Design

This was a mixed-method study that assessed the rational use of antibiotics in the management of CAP using hospital patient charts at Ndola Teaching Hospital (NTH), as well as prescribers' knowledge of the availability of Standard Treatment Guidelines version 2020 and their practice in the management of CAP. This design was chosen because it minimizes the rate of change in behaviour for prescribers that is likely to happen in a prospective.

4.2. Study Site

This study was carried out from NTH which is one of Zambia's main referral hospitals, and is located in Ndola, the provincial capital of the Copperbelt province. It has a bed capacity of 851, and it predominantly serves referrals from Zambia's northern regions, including Copperbelt, Northwestern, Luapula, Muchinga, Northern, and parts of Central [

39].

4.3. Sampling Procedures

For the retrospective review, all adult patients admitted to hospital wards between November 2023 and August 2024 were included, provided they met the inclusion criteria. This period was selected due to the high incidence of pneumonia cases, making it a critical time frame for analysis.

4.4. Inclusion Criteria

Patients admitted from NTH from November 2023 to August 2024, discharged with the diagnosis of pneumonia or a pneumonia-related disease.

NTH being an adult hospital, only patients aged 15 and above will be considered.

4.5. Only Patients with Confirmed CAP Disease

To assess prescribers’ perception in management of CAP, this study will only consider prescribers who have managed CAP at NTH in the past 1 year (March 2023 to March 2024)

4.6. Exclusion Criteria

Patients who failed to show an infiltrate consistent with pneumonia when a chest x-Ray was performed within 24 hours of hospital admission.

4.7. Data Collection

Data was collected from the NTH hospital wards where the AMS committee has been conducting antibiotic audits. The following predetermined patient information was extracted for each included patient from admission files, medication charts, and laboratory data: age, gender, length of stay, allergy status, comorbidities, most prescribed antibiotics, laboratory and clinical data relevant to infections, ordered microbiological tests, and laboratory results turnaround time. Based on data on admission and severity according to CURB-65 will be calculated. The dependent variable for the quantitative research was the in-hospital patient mortality variable.

4.8. Data Analysis

Data was collated using excel® and numbers and percentages were used to represent categorical variables and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 [

40]. The Chi-square test will be used to compare the responses of the two groups (mortality and no mortality). A bivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess factors that determine the likelihood of in-hospital mortality or not and variables that demonstrated a possible association from bivariate analysis (p < 0.30) were entered into the multivariable model. The results were reported as odds ratios (OR). An OR >1 indicated an increased likelihood of accepting the vaccine, whereas an OR<1 indicated that the likelihood of accepting the vaccine dropped. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P < 0.05.

5. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was sought from the Tropical Disease Research Centre Ethics Committee (TDREC/09/099/24) issued on 11/06/2024. Permission was also obtained from the Ministry of Health (MoH) office of the Provincial Medical Officer, Copperbelt Province to carry out the study at the Ndola Teaching Hospital.

6. Results

6.1. Patient File Data

6.1.1. Demographic Data

Out of 142 patient files assessed, the majority were female (n = 87, 61.3%), with most patients under 65 years old (n = 98, 69.0%). The Internal Medicine Department contributed the majority of files (n = 141, 99.3%). Ceftriaxone was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Data.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Data.

| SN |

VARIABLE |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| 1 |

Gender |

Male |

55 |

38.7% |

| Female |

87 |

61.3% |

| 2 |

Age (Above 65) |

Yes |

44 |

31.0% |

| No |

98 |

69.0% |

| 3 |

Hospital Department |

Internal Medicine Department |

141 |

99.3% |

| Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department |

1 |

0.7% |

6.1.2. Factors that Influenced In-Hospital Patient Mortality

The distribution of factors influencing in-hospital mortality for patients with community-acquired pneumonia is summarized in

Table 3. A Chi-Square test revealed significant associations between in-hospital mortality and several variables. These include gender (p < 0.000), age (over 65) (p < 0.000), length of hospital stays (p < 0.000), and the CURB-65 score on admission (p < 0.000).

Other significant factors were patient allergies (p < 0.000), co-morbidities (p < 0.000), the presence of X-ray results (p < 0.000), antibiotics listed on the treatment file (p < 0.000), number of antibiotics prescribed (p < 0.000), pathogen culture testing (p < 0.000), and the turnaround time for lab culture results (p < 0.000). Additionally, patient management did not align with the 2020 national Standard Treatment Guidelines and it showed a strong association with in-hospital patient mortality (p < 0.000).

Interestingly, the CURB-65 score calculated or indicated on admission (p = 0.735) was found to be independent of in-hospital mortality. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive patient management, timely diagnostic testing, and adherence to national guidelines in influencing patient outcomes.

6.1.3. Variables Associated With In-Hospital Patient Mortality

In the multivariable logistic regression model, age above 65 years was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (aOR: 0.295, CI: 0.173-0.418, p < 0.000), indicating a higher mortality risk in older patients. Length of hospital stay also had a significant association (aOR: 0.118, CI: 0.058-0.178, p < 0.000), along with patient allergies (aOR: 0.576, CI: 0.247-0.904, p < 0.001). Management of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) aligned with the national Standard Treatment Guidelines (2020) (aOR: -0.275, CI: -0.405 to -0.146, p < 0.000), as detailed in

Table 4.

6.2. Prescribers Perception on Cap Management

In this study, 34 prescribers shared their perceptions on the management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) at Ndola Teaching Hospital (NTH). The majority of respondents were male (n = 18, 52.9%), with most falling within the age range of 20–30 years (n = 26, 76.5%). Notably, a significant proportion of prescribers (n = 30, 88.2%) believed that NTH is adequately equipped to diagnose and manage CAP. However, about half of the participants (n = 14, 41.2%) had not seen the Zambian Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) that are meant to guide their prescribing practices. These findings highlight the need for better dissemination of guidelines.

6.2.1. Challenges Encounted While Managing Cap at NTH

The majority of prescribers cited key challenges in managing Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP), including the unavailability of correct antibiotics and oxygen (n = 11, 32.4%), as well as delays in lab results and the lack of culture bottles (n = 10, 29.4%). These issues significantly impact their ability to practice the rational use of medicines for CAP management. Other challenges, as outlined in

Table 6, further highlight the need for improved resource availability and system efficiency to enhance patient care and adherence to treatment guidelines.

6.2.2. Suggested Solutions to Better Manage Cap at NTH

The study revealed that 29.4% of respondents recommended increasing pharmacy staff on wards, expanding antibiotic coverage, and enhancing community awareness to improve CAP management at Ndola Teaching Hospital (NTH). Another 29.4% suggested making culture bottles available, upgrading lab equipment, and reducing laboratory turnaround time. Updating the Zambian Standard Treatment Guidelines was noted by 11.8% as essential for better CAP treatment protocols, while 8.8% saw the need for a functional portable chest X-ray machine. However, 20.6% felt that no changes were necessary. These suggestions as outlined in

Table 7, highlight specific areas to address CAP management challenges and improve patient outcomes at NTH.

7. Discussion

In managing community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adults at NTH, the Zambia National Standard Treatment Guidelines recommend a stepwise approach. The first-line treatment includes Amoxicillin or Co-Amoxiclav, typically administered in divided doses. If there is no improvement, second-line treatment consists of Ceftriaxone or Cefotaxime, administered intravenously. For severe cases, particularly where staphylococcal pneumonia is suspected, third-line treatment involves adding Cloxacillin and possibly Macrolides, such as Erythromycin or Azithromycin, especially in adolescents. This rational use of antimicrobials ensures targeted therapy, reducing resistance while improving patient outcomes [

35].

This study examined the demographic data and factors influencing rational use of antibiotics in the management of CAP at Ndola Teaching Hospital (NTH). Among the 142 patient files assessed, majority were female (61.3%), with most patients under 65 years old (69.0%). This demographic pattern aligns with previous findings suggesting a greater incidence of CAP in younger adults, while older populations tend to face higher morbidity and mortality rates due to comorbid conditions [

5,

18].

Ceftriaxone was also found as most frequently prescribed antibiotic. This highlighted a typical approach to treating CAP, but it also raises questions about compliance with the national Standard Treatment Guidelines [

41]. Such adherence is crucial for optimizing rational antibiotic use and preventing resistance development, particularly given the study’s findings indicating that deviations from these guidelines were strongly associated with increased in-hospital mortality (p < 0.000). These results emphasize the need for standardized protocols in antibiotic selection to ensure the rational use of antibiotics [

16].

Several significant associations were identified in relation to in-hospital mortality among patients with CAP, including age, length of hospital stay, and the CURB-65 score. Interestingly, while age over 65 years showed a strong correlation with increased mortality (aOR: 0.295), the CURB-65 score did not significantly influence mortality rates (p = 0.735). This discrepancy suggests that, while the CURB-65 score is a useful tool for initial risk stratification, other factors such as comorbidities and timely treatment interventions may have a more profound impact on patient outcomes [

21,

23].

The study also highlighted the critical role of comprehensive patient management, including timely diagnostic testing and a multi-disciplinary approach to care [

2]. The presence of co-morbidities and the management of allergies were also significant factors impacting patient mortality, emphasizing the complexity of CAP cases and the necessity for tailored treatment plans that address individual patient needs [

18,

42].

Further, the perceptions of prescribers regarding CAP management at NTH revealed significant insights. Although a majority of prescribers believed the hospital was adequately equipped to manage CAP, nearly half had not seen the Zambian Standard Treatment Guidelines. This gap highlights the need for better dissemination of clinical guidelines to enhance prescriber knowledge and adherence to evidence-based practices [

43]. The challenges identified by prescribers, including the unavailability of correct antibiotics and delays in laboratory results, reflect systemic issues that hinder the rational use of antibiotics. Addressing these challenges like providing a wider spectrum of antibiotics, prescribing withing the guidelines and access to laboratory results are essential for improving patient care and outcomes [

44].

8. Study Limitation

Several limitations were expected in this study.

Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study and the findings could not be easily extended to other hospital settings.

Secondly, the setting was Ndola, at Ndola Teaching Hospital and a representation from an academic health system which limits the generalizability of the findings.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the critical need for improved adherence to national treatment guidelines and better resource allocation to ensure the rational use of antibiotics in managing community-acquired pneumonia. Interventions aimed at enhancing prescriber education, improving diagnostic and treatment resources, and fostering a collaborative approach among healthcare professionals could significantly reduce in-hospital mortality rates and improve overall patient management for CAP. Further research is warranted to explore the long-term impacts of these interventions and develop comprehensive strategies to optimize antibiotic use in diverse clinical settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hope Kalasa; Methodology, Hope Kalasa; Software, Hope Kalasa; Formal analysis, Hope Kalasa; Investigation, Hope Kalasa; Resources, Hope Kalasa; Data curation, Hope Kalasa; Writing – original draft, Hope Kalasa; Writing – review & editing, Hope Kalasa, Zara Tariq, Elimas Jere and Derrick Munkombwe; Supervision, Zara Tariq, Elimas Jere and Derrick Munkombwe; Project administration, Hope Kalasa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Ndola Teaching Hospital. Ethical approval was obtained from the Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC) Ethics Review Committee (Approval Number: TDREC/09/099/24) issued on 11/06/2024. prior to the commencement of data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and all participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, access to certain data may be restricted to protect patient confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The research was conducted independently, and no external financial or personal relationships influenced the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or publication.

Appendix A. Data Collection Tools

Appendix A.1. Demographic information from the patient file

1. Hospital Department

- a)

Internal Medicine Department

- b)

Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department

- c)

Surgery Department

- d)

High Dependance Department

2. Year of Birth for the patient: ______________________________

3. Gender for the patient

- a)

Male

- b)

Female

Appendix A.2. Patient Data

4. Date of Admission to the hospital: _____________________________

5. Date of Discharge from the hospital: __________________________________

6. CURB-65 score on admission calculated and indicated:

7. If calculated/indicted, what was the score?

- a.

0

- b.

1

- c.

2

- d.

3

- e.

4

8. CURB-65 score on admission based on the patient file

- a)

Confusion

- b)

BUN

- c)

Respiration ≥ 30/min

- d)

SBP < 90mmHg

- e)

Age ≥ 65

9. Allergy

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

10. If yes, which allergy?

11. In-hospital mortality

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

11. Is the X-ray result present?

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

12. If present, does it show a pneumonia infection?

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

Appendix A.3. Information on antibiotic treatment

Antibiotic

treatment

started

(Name of

Department) |

Start

date |

Antibiotic |

Dose |

Formulation |

Dose-

interval |

Stop date +

# doses

given |

Comments (including

information on length of

prescription and switch if any) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic

| |

|

Yes |

No |

Reason for Switch |

| 1 |

Other i.v. indications present |

☐ |

☐ |

|

| 2 |

Oral route compromised? |

☐ |

☐ |

|

Appendix A.4. Lab and microbiological data

13. Pathogen Culture testing indicated in the patient file?

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

14. What was the turnaround time for lab culture results?

- a)

Within 24hrs

- b)

Within 48hrs

- c)

Within 72hrs

- d)

After 72hrs

- e)

No results

Clinical data

15. Does the management of the patient align with the National StandardTreatment Guidelines? (Confirm with the STG v 2020)

Appendix A.6. Qualitative Data

1. Do you think STG v 2020 has adequate information to about the management of CAP in adults?

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

- c)

I have not seen the guidelines

2. If No, what do you think should be added or removed from the guidelines?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. Do you think NTH is adequately equipped to diagnose or manage CAP?

- a)

Yes

- b)

No

- c)

Not Sure

4. If No, what support would you need to better manage CAP at NTH

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. What are some of the challenges you faced while managing CAP at NTH?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix B. Research Workplan 2024

| Responsible Person |

Activity |

Feb 24 |

Mar 24 |

Apr 24 |

May – Jul 24 |

Aug – Sep 24 |

Oct 24 |

| Hope Kalasa |

Proposal development and submission |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hope Kalasa |

Ethics Clearance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hope Kalasa |

Data collection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hope Kalasa |

Sorting, tabulating, coding and analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hope Kalasa |

Data analysis and report writing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hope Kalasa |

Dissemination of Report findings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix C. Research Budget

| CATEGORY OF ITEMS |

UNIT |

UNIT PRICE COST |

QUANTITY |

TOTAL |

| Plain papers |

Ream |

ZMW 200.00 |

3 |

ZMW 600.00 |

| Printing |

Each |

ZMW 500.00 |

6 Copies |

ZMW 3000.00 |

| Binding the Booklet |

Each |

ZMW 500 |

3 |

ZMW 2,000.00 |

| Data Collection and Analysis |

1 |

ZMW 11,500 |

1 |

ZMW 11,500.00 |

| Ethical Approval |

1 |

ZMW 2500 |

1 |

ZMW 2,500.00 |

TOTAL

ZMW 19,600.00 |

References

- Shoar, S.; Musher, D. 1498. Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, S751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Report on Surveillance 2014. WHO 2014 AMR Rep. 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2015.

- Graham, K.; Sinyangwe, C.; Nicholas, S.; King, R.; Mukupa, S.; Källander, K.; Counihan, H.; Montague, M.; Tibenderana, J.; Hamade, P. Rational Use of Antibiotics by Community Health Workers and Caregivers for Children with Suspected Pneumonia in Zambia: A Cross-Sectional Mixed Methods Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, A.K.; Shafiq, N.; Singh, G.; Ray, P.; Gautam, V.; Agarwal, R.; Muralidharan, J.; Arora, P. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Resource Constrained Environments: Understanding and Addressing the Need of the Systems. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance, World Health Organisatin. WHO Glob. Strateg. Contain. Antimicrob. Resist. 2001, WHO/CDS/CS, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, E.; Weil, D.E.; Raviglione, M.; Nakatani, H. The WHO Policy Package to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlet, J.; Collignon, P.; Goldmann, D.; Goossens, H.; Gyssens, I.C.; Harbarth, S.; Jarlier, V.; Levy, S.B.; N’Doye, B.; Pittet, D.; et al. Society’s Failure to Protect a Precious Resource: Antibiotics. Lancet 2011, 378, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sema, F.D.; Asres, E.D.; Wubeshet, B.D. <p>Evaluation of Rational Use of Medicine Using WHO/INRUD Core Drug Use Indicators at Teda and Azezo Health Centers, Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia</P>. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2021, 10, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekaw, H.; Derebe, D.; Melese, W.M.; Yismaw, M.B. Antibiotic Prescription Pattern, Appropriateness, and Associated Factors in Patients Admitted to Pediatric Wards of Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital, Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.; Momattin, H.; Hinedi, K. Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in the Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in a General Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalungia, A.C.; Mwambula, H.; Munkombwe, D.; Marshall, S.; Schellack, N.; May, C.; Jones, A.S.C.; Godman, B. Antimicrobial Stewardship Knowledge and Perception among Physicians and Pharmacists at Leading Tertiary Teaching Hospitals in Zambia: Implications for Future Policy and Practice. J. Chemother. 2019, 31, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, J.; Zahra, F.; Cannady, P., Jr. Antimicrobial Stewardship. StatPearls 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ligogo, B.L. Rational Use Of Antibiotics Among Patients Admitted To Critical Care Units At Kenyatta National Hospital And Its Impact On Clinical Outcomes. 2020.

- Mi, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, L.; Huang, L.; Chen, L.; Song, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, M. The Drug Use to Treat Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Med. (United States) 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston, S.J. Community—Acquired Pneumonia in Sub—Saharan Africa. 2016, 1–32.

- Ferreira-Coimbra, J.; Sarda, C.; Rello, J. Burden of Community-Acquired Pneumonia and Unmet Clinical Needs. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanJoaquin, M.A.; Allain, T.J.; Molyneux, M.E.; Benjamin, L.; Everett, D.B.; Gadabu, O.; Rothe, C.; Nguipdop, P.; Chilombe, M.; Kazembe, L.; et al. Surveillance Programme of IN-Patients and Epidemiology (SPINE): Implementation of an Electronic Data Collection Tool within a Large Hospital in Malawi. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr Richard. Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 740–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L.; Nelson, J.C.; Jackson, L.A. Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Immunocompetent Seniors. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.T.K.; Hoang, T.T.; Van, P.H.; Tu, L.; Graham, S.M.; Marais, B.J. Encouraging Rational Antibiotic Use in Childhood Pneumonia: A Focus on Vietnam and the Western Pacific Region. Pneumonia 2017, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, J.; Bolíbar, I.; Serra-Prat, M.; Roig, J.; Hospital, I.; Carandell, E.; Agustí, M.; Ayuso, P.; Estela, A.; Torres, A.; et al. . New Evidence of Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Population-Based Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlay, J.P.; Fine, M.J. Testing Strategies in the Initial Management of Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prina, E.; Ranzani, O.T.; Torres, A.; Paulo, S.; Paulo, S. Since 20 Elsevier Has Created a COVID-19 Resource Centre with Free Information in English and Mandarin on the Novel Coronavirus COVID- Research That Is Available on the COVID-19 Resource Centre - Including This for Unrestricted Research Re-Use A. 2020, No. January. 20 January.

- Schuetz, P.; Kutz, A.; Grolimund, E.; Haubitz, S.; Demann, D.; Vögeli, A.; Hitz, F.; Christ-Crain, M.; Thomann, R.; Falconnier, C.; et al. Excluding Infection through Procalcitonin Testing Improves Outcomes of Congestive Heart Failure Patients Presenting with Acute Respiratory Symptoms: Results from the Randomized ProHOSP Trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 175, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranga, A.; Espana, P.P.; Bilbao, A.; Quintana, J.M.; Arriaga, I.; Intxausti, M.; Lobo, J.L.; Tomas, L.; Camino, J.; Nunez, J.; et al. Duration of Antibiotic Treatment in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Ang, J.Y. COVID-19 Infection in Children: Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 24, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.L.; Achonu, C.; Buchan, S.A.; Brown, K.A.; Lee, B.; Whelan, M.; Wu, J.H.; Garber, G. COVID-19 Infections among Healthcare Workers and Transmission within Households. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.S. Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. 2018, 25, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, R.S. Nominations Invited For Indian Chest Society Orations / Awards. Society 2006, 147001, 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, P.; Epstein, S.; Moore, C.C.; Bueno, J. Atypical Pneumonia : Definition, Causes, and Imaging Features. 2019, No. 6, 720–741.

- Høgli, J. Appropriate Antibiotic Prescribing in Community-Acquired Pneumonia in a Norwegian Hospital Setting. 2015, No. June.

- Ministry-of-Health-Zambia. Zambia Standard Treatment Guidelines. 2020.

- Lakbar, I.; De Waele, J.J.; Tabah, A.; Einav, S.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Leone, M. Antimicrobial De-Escalation in the ICU: From Recommendations to Level of Evidence. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterton, R.G. Antibiotic De-Escalation. Crit. Care Clin. 2011, 27, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Geneva. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. World Heal. Organ. 2017, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hachizovu, S.; Chaponda, M.; Manyando, C.; Mubikayi, D.; Mulenga, M.; Makupe, A. Characteristics of People Brought in Dead at the Ndola Teaching Hospital in Zambia between 2012 and 2016. Med. J. Zambia 2019, 46, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBMCorp. Downloading IBM SPSS Statistics 20. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-20 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Jambo, A.; Edessa, D.; Adem, F.; Gashaw, T. Appropriateness of Antimicrobial Selection for Treatment of Pneumonia in Selected Public Hospitals of Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, E.; Chaize, G.; Fievez, S.; Féger, C.; Herquelot, E.; Vainchtock, A.; Timsit, J.F.; Gaillat, J. The Impact of Comorbidities and Their Stacking on Short- and Long-Term Prognosis of Patients over 50 with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, W.; Mudenda, W.; Chikatula, E.; Chambula, E.; Mwanashimbala, B.; Chikuta, M.; Masaninga, F.; Songolo, P.; Vwalika, B.; Kachimba, J.S.; et al. Prescribing Patterns and Medicine Use at The. 2016, 43, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mudenda, S.; Chilimboyi, R.; Matafwali, S.K.; Daka, V.; Mfune, R.L.; Kemgne, L.A.M.; Bumbangi, F.N.; Hangoma, J.; Chabalenge, B.; Mweetwa, L.; et al. Hospital Prescribing Patterns of Antibiotics in Zambia Using the WHO Prescribing Indicators Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings and Implications. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2024, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilma, Z.; Mekonnen, T.; Siraj, E.A.; Agmassie, Z.; Yehualaw, A.; Debasu, Z.; Tafere, C.; Ararsie, M. Assessment of Prescription Completeness and Drug Use Pattern in Tibebe-Ghion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiye, A.A.; Woldamo, A.; Kedir, H.M.; Tadesse, T.A. International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review Completeness and Legibility of Handwritten Prescriptions at Ethiopian General Hospital: Facility-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int.J.Curr.Res.Aca.Rev 2019, 7, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Admassie, E.; Tesfaye, W.H.; Begashaw, B.; Hailu, W. Assessment of Drug Use Practices and Completeness of Prescriptions in Gondar University Teaching Referral Hospital Article In. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2012, 4, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Ababa, A.; Assefa, T.; Abera, B.; Bacha, T.; Beedemariam, G. Prescription Completeness and Drug Use Pattern in the University. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2018, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Anagaw, Y.K.; Limenh, L.W.; Geremew, D.T.; Worku, M.C.; Dessie, M.G.; Tessema, T.A.; Demelash, T.B.; Ayenew, W. Assessment of Prescription Completeness and Drug Use Pattern Using WHO Prescribing Indicators in Private Community Pharmacies in Addis Ababa: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2023, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO_DAP_93.1.Pdf. 1993, p. 92. WHO. WHO_DAP_93.1.Pdf. 1993, p. 92. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/60519/WHO_DAP_93.1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Mahomedradja, R.F.; Schinkel, M.; Sigaloff, K.C.E.; Reumerman, M.O.; Otten, R.H.J.; Tichelaar, J.; van Agtmael, M.A. Factors Influencing In-Hospital Prescribing Errors: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 1724–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzan, M.; Alwhaibi, M.; Almetwazi, M.; Alhawassi, T.M. Prescribing Errors and Associated Factors in Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, M.M.; Elewa, H.A.; El-Kholy, A.A.E.M.S. Perceptions and Attitudes of Hospital’ Prescribers towards Drug Information Sources and Prescribing Practices. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).