1. Introduction

The regulation of biological rhythms is a fundamental aspect of human physiology, linked to the concept of circadian rhythms, which govern a wide array of bodily functions over a roughly 24-hour cycle. These rhythms are driven by the circadian clock, a complex network of genes and proteins that modulate key processes such as sleep-wake cycles, hormonal secretion, metabolic functions, and cognitive performance. Disruptions to the circadian clock, whether due to environmental factors, lifestyle choices, or underlying health issues, can lead to a variety of adverse health outcomes, including sleep disorders, metabolic syndrome, and mood disturbances (Chen et al., 2018).

In recent years, a growing body of literature has focused on the role of pharmacological agents, referred to as chronobiotics, in the modulation of the circadian clock. Chronobiotics can be defined as drugs or natural compounds that promote the synchronization of biological rhythms, enhancing the alignment of physiological processes with environmental cues. These agents have shown promise not only in the treatment of circadian rhythm disorders, such as delayed sleep phase disorder, but also in addressing broader health challenges associated with circadian misalignment. The identification and characterization of chronobiotic compounds necessitate a systematic approach to cataloging existing research, elucidating their mechanisms of action, and assessing their clinical utility. This article aims to provide a comprehensive database of drugs and compounds with chronobiotic properties, detailing their pharmacological profiles, therapeutic applications, and potential side effects. By compiling this information, we seek to establish a valuable resource for researchers and clinicians alike, facilitating the translation of chronobiological principles into effective therapeutic strategies (Solovev and Golubev, 2024).

Moreover, understanding the symbiotic relationship between circadian rhythms and pharmacology has implications that extend beyond isolated medical conditions. As society grapples with the increasing prevalence of shift work, frequent travel across time zones, and lifestyle factors that contribute to circadian disruption, the need for effective chronobiotic therapies becomes ever more pressing (Cha et al., 2019).

This database not only serves as a reference point for existing knowledge but also aims to inspire future research that could further elucidate the role of circadian modulation in health and disease.The exploration of chronobiotics represents a promising frontier in the intersection of chronobiology and pharmacology. This article endeavors to contribute to the growing body of knowledge in this field, offering a structured overview of compounds capable of influencing the circadian clock and their implications for future clinical applications on different levels of life organisation (Robles-Piedras et al., 2024).

2. Materials and Methods

Data were obtained from a diverse array of scientific literature, including peer-reviewed journals, clinical trial databases, and existing biochemical repositories. Keywords such as “Compound name”, "chronobiotic," "circadian rhythm," and "biological clock", “circadian clock modulator”, “circadian rhythm modulator”, “сhronodisruptor” were utilized for comprehensive literature searches across databases like PubMed, Google scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science.

The curation process consisted (Odell et al., 2017) of several key stages:

Data Acquisition - Systematic retrieval of published studies focusing on the effects of compounds on circadian rhythms.

Established parameters for inclusion were:

Peer-reviewed articles published within the last five decades.

Studies demonstrating acute or chronic effects on circadian rhythms.

Compounds documented as in vitro and in vivo studies.

Data Extraction

Information on compound identity, structure, mechanism of action, effect, targets and observed outcomes was meticulously extracted.

Quality Assessment: Each study underwent a thorough quality assessment using established criteria to evaluate study design, sample size, and reproducibility of results.

Data Validation: Cross-validation of extracted data with multiple studies was performed to ensure accuracy and reliability.

All data curation activities adhered to ethical standards regarding the utilization of published research. The database ensures that intellectual property rights of original researchers are respected by appropriately citing sources and providing links to original publications.

The finalized dataset was implemented into a relational database management system, designed to support user-friendly queries and retrieval of information. The database is accessible via a web interface, enabling users to perform searches based on compound characteristics, effects, and study parameters.

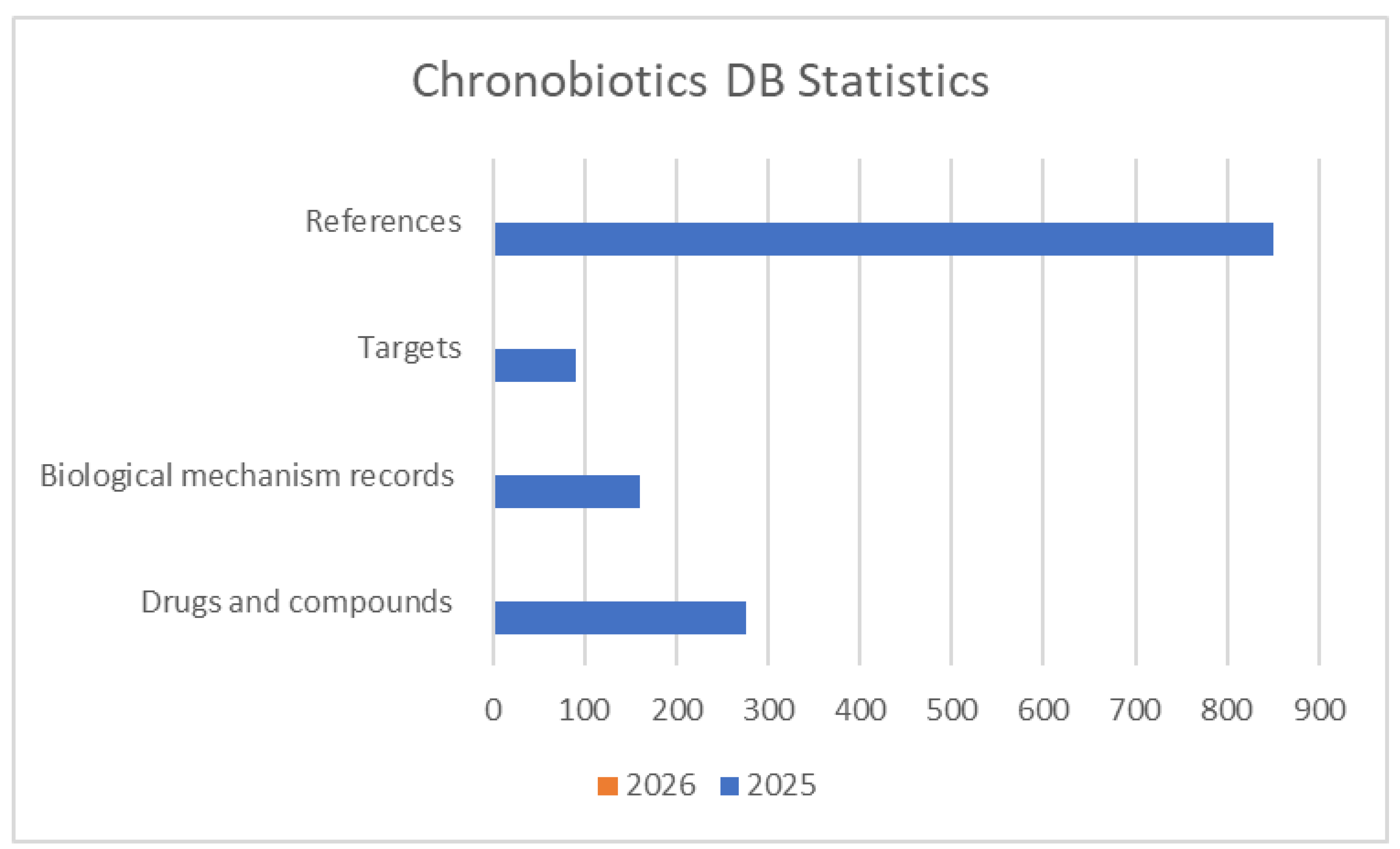

The Chronobiotics Database consolidates findings from numerous studies on the influence of chronobiotics on biological rhythms. The database currently comprises a comprehensive collection of more than 845 unique references, including peer-reviewed journal articles, preclinical trials, and experimental reports and datasets. These sources were curated through systematic searches in established scientific repositories such as PubMed and PubChem (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Google Scholar (

https://scholar.google.com/) and Web of Science using keywords related to circadian rhythms, aging, longevity, chronobiotics, biological age.

Data extracted from these sources include primary details, such as compound structures, mechanisms of action, and effects on circadian rhythms, as well as secondary data like experimental conditions and outcomes. This comprehensive and systematic dataset forms the backbone of the Chronobiotics Database, facilitating a deeper understanding of chronobiotic compounds and their potential for circadian rhythm modulation.

The data curation process involved several essential stages, each designed to ensure the accuracy, consistency, and ethical integrity of the collected information.

Data Acquisition: a systematic approach was employed to retrieve relevant studies focusing on the effects of various compounds on circadian rhythms. The inclusion criteria for studies were:a) Peer-reviewed articles published in the past two decades.b) Research demonstrating both acute and chronic effects on circadian rhythms.c) Compounds studied through both in vitro and in vivo methodologies.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Detailed information was extracted for each compound, including its identity, structure, mechanism of action, biological targets, effects, and observed outcomes. Each study underwent a rigorous quality assessment based on study design, sample size, and reproducibility of results to ensure reliability.

Cross-validation of extracted data was performed by comparing results across multiple studies to confirm accuracy and consistency if the study mentioned is not the only existing.

To facilitate seamless data integration, standardization protocols were employed:a) Compound names were normalized following the Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) nomenclature (if available).

b) Controlled vocabularies were established for biological terms relating to chronobiotic effects to ensure uniformity across entries.

Ethical Considerations: the curation process adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring respect for intellectual property rights. Proper citation of sources and links to original publications were provided to uphold academic integrity.

Database Implementation: the curated data was integrated into a relational database management system, designed to support easy queries and data retrieval. The database is accessible via a user-friendly web interface, allowing users to search by compound characteristics, effects, and study parameters.

2.1. Database Organization (Primary and Secondary Data)

The difference between primary and secondary data in the development of ChronobioticsDB is major for ensuring accuracy and comprehensiveness. Primary data consists of information created specifically for the database, often through manual curation by expert researchers. This includes molecular structures (e.g., SMILES strings), mechanisms of action, and biological target data, which are entered directly into the database through specialized interfaces. Primary data may also originate from in-house experimental studies, such as investigations into compound-target interactions, which undergo rigorous validation before integration. Additionally, external sources like PubChem or DrugBank (Knox et al., 2024). can be treated as primary data when manually curated and standardized to align with the database’s criteria. Importantly, primary data has no external references—it is created or adapted exclusively for ChronobioticsDB.

Secondary data, on the other hand, consists of pre-existing information sourced from external publications, databases, or regulatory reports that were originally compiled for purposes unrelated to ChronobioticsDB. Examples include peer-reviewed articles describing compound properties, FDA approval statuses, or datasets from repositories like PubChem and UniProt or RCSB PDB (Bittrich et al., 2024). Unlike primary data, secondary data is linked to external references. There is also strict scrutiny and adaptation to ensure alignment with the database’s standards, involving cross-referencing multiple sources and linking entries to their original references for transparency. Secondary data fulfill the database by providing broader context.

The synergy between these two types of data is critical: primary data offers specificity and originality tailored to ChronobioticsDB’s objectives, while secondary data expands its scope by integrating established knowledge. For instance, a compound’s mechanism of action (primary data) might be contextualized using pharmacological profiles from DrugBank (Knox et al., 2024) (secondary data), creating a multidimensional view of its therapeutic potential. While challenges persist in balancing the dynamic nature of scientific knowledge with the need for stability in the database, this combination ensures that ChronobioticsDB remains a reliable repository and a dynamic tool for researchers exploring circadian rhythm modulation.

2.2. Database Architecture

The database architecture of our project is constructed on a relational model and employs PostgreSQL as the database management system (DBMS). The database is organized around the central table, Chronobiotic, which stores information pertaining to chemical compounds. The remaining tables are linked to the central table through foreign keys and many-to-many relationships, ensuring both flexibility and data integrity. The database architecture has been designed in accordance with the project's requirements, including support for both primary and secondary data.

Core Components of the Architecture

Central Table: Chronobiotic

This table serves as the core component and contains primary information about chemical compounds. It includes fields for storing the compound's name, structure, description, FDA status, references to external resources, and other relevant data.

Key Features are Unique Fields: the fields gname, smiles, molecula, and iupacname ensure the uniqueness of each compound.

Relationships with Other Tables: The Chronobiotic table is linked to the synonyms, target, mechanism, and class tables through one-to-many and many-to-many relationships.

2.2.2. Auxiliary Tables

The auxiliary tables (synonyms, target, mechanism, class) are utilized to store supplementary information that extends and enriches the data on chemical compounds:

One-to-Many Relationships: The synonyms table is connected to Chronobiotic via the foreign key originalbiotic.

Many-to-Many Relationships: The target, mechanism, and class tables are linked to Chronobiotic through intermediary tables, which are automatically generated by Django.

Schema of Table Relationships

Chronobiotic → synonyms: A single compound may have multiple synonyms.

Chronobiotic → target: A single compound may interact with multiple targets, and a single target may be associated with multiple compounds.

Chronobiotic → mechanism: A single compound may exhibit multiple mechanisms of action, and a single mechanism may be associated with multiple compounds.

Chronobiotic → class: A single compound may belong to multiple classes, and a single class may encompass multiple compounds.

Technologies and Tools

DBMS: PostgreSQL, a robust and reliable relational database, provides high performance and supports complex queries (Simkovics, S. and Petersgasse, P., 1998).

ORM: Django ORM is employed for database interactions at the Python code level. This eliminates the need for manual SQL query writing and facilitates efficient data management. (Holovaty. and Willison, 2003.)

Indexes: Indexes have been created on frequently queried fields, such as gname, smiles, and targetsname, to optimize search performance.

Migrations: Django's built-in migration system allows for seamless modifications to the database structure without data loss.

3. Ensuring Data Integrity and Security

Foreign Keys: All inter-table relationships are implemented through foreign keys, ensuring data integrity.

Unique Constraints: Unique fields (gname, smiles, molecula, iupacname) prevent record duplication.

Role-Based Access Control: Database access is restricted at the user and role levels, ensuring data security.

Encryption: Confidential data is stored in an encrypted format.

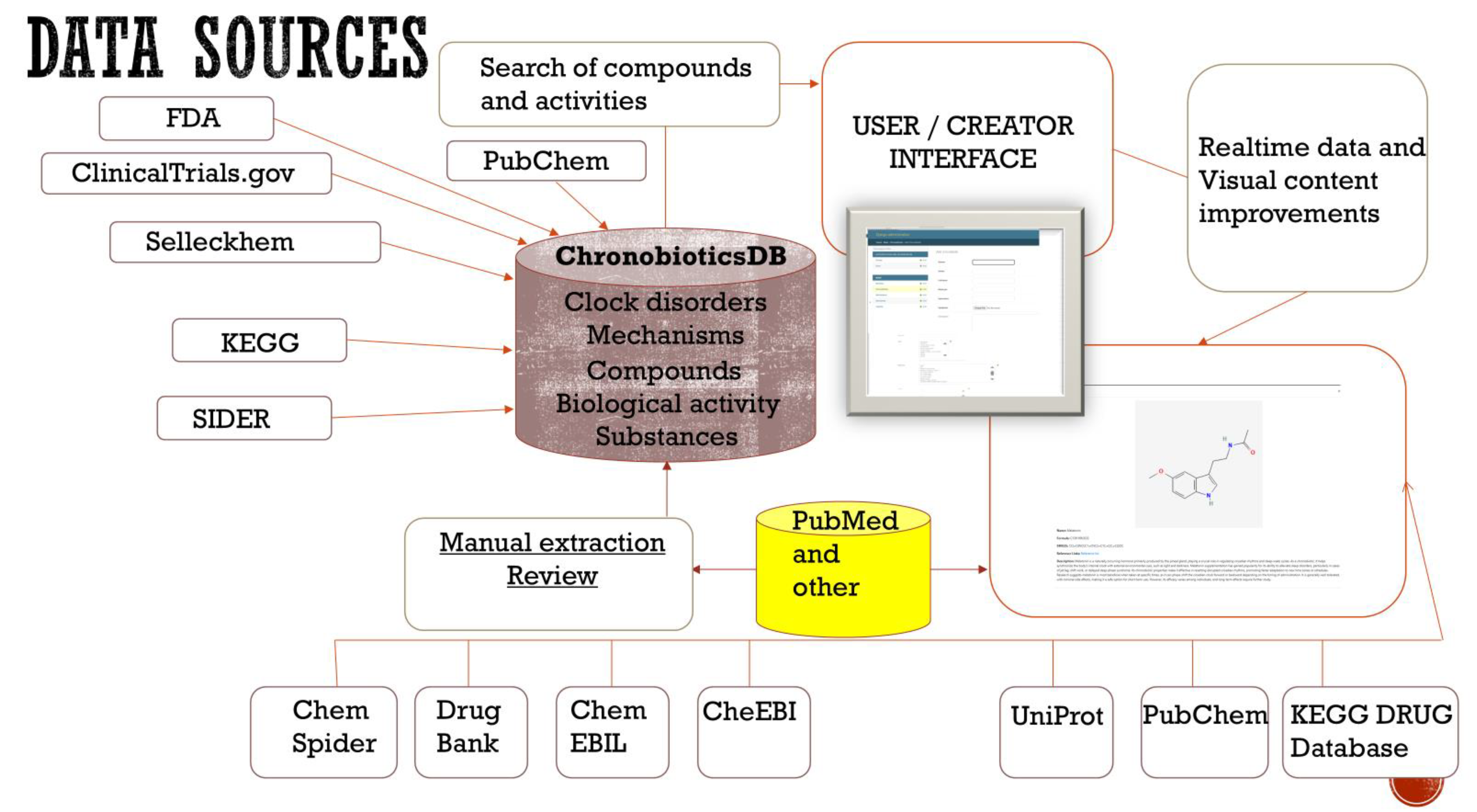

Figure 1.

The model of “ChronobioticsDB”.

Figure 1.

The model of “ChronobioticsDB”.

4. Results

ChronobioticDB (accessible at

https://chronobiotic.ru) is an online database designed to provide a centralized resource on chronobiotic compounds (drugs or molecules that modulate circadian rhythms), addressing the lack of a unified knowledge base in this domain

chronobiotic.ru. The web interface is organized into two complementary components that together support both broad data dissemination and expert curation. The publicly accessible front-end displays a catalog of known and candidate chronobiotics in a searchable, filterable table, enabling users to quickly find entries by compound name, molecular formula, or chemical structure (SMILES notation). Each entry is summarized with key fields such as the compound’s Name, Molecular Formula, and FDA Approval Status, and users can click an entry to view additional details (e.g., a descriptive synopsis and reference links) in an intuitive pop-up panel. This user-friendly interface allows researchers and general users to easily explore the database and retrieve information, thereby promoting accessibility and dissemination of chronobiotic-related data.

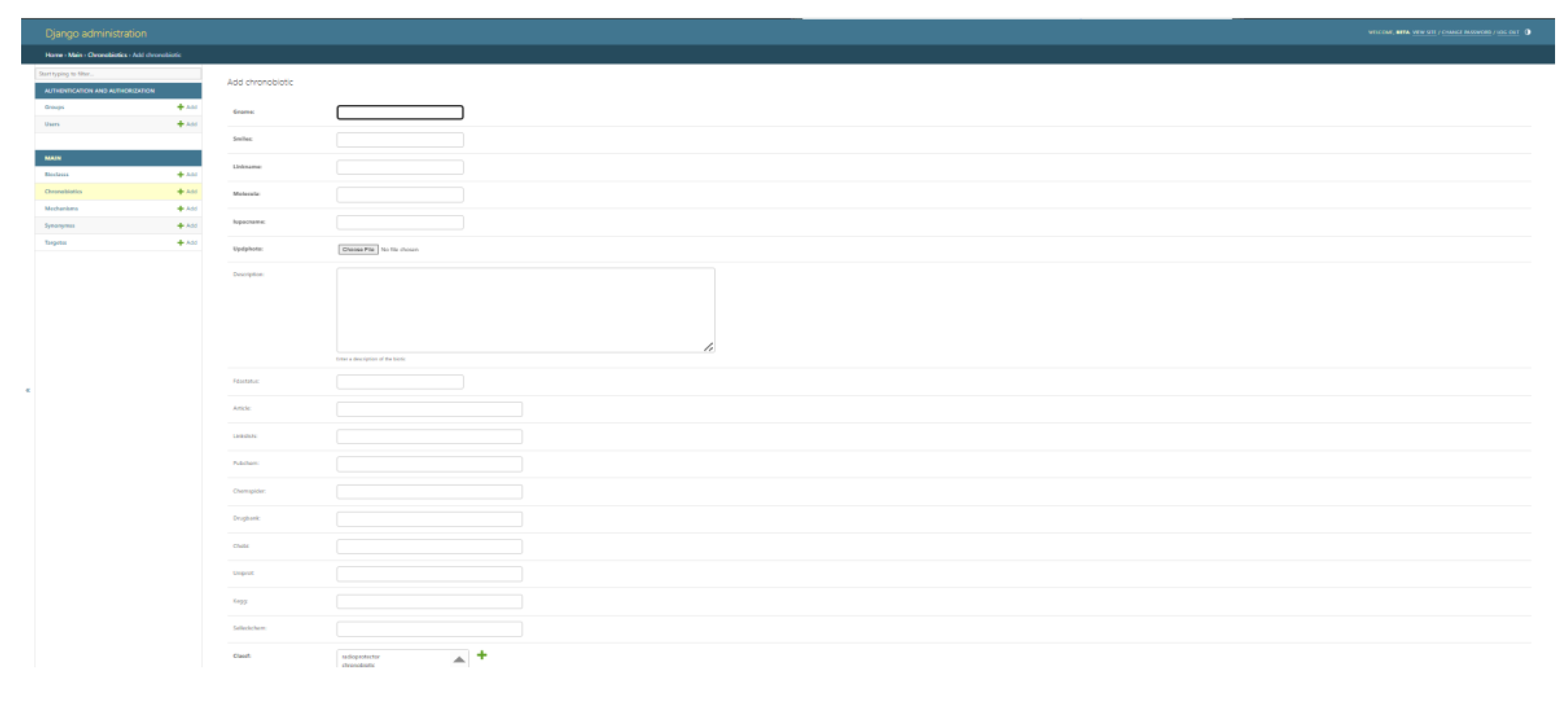

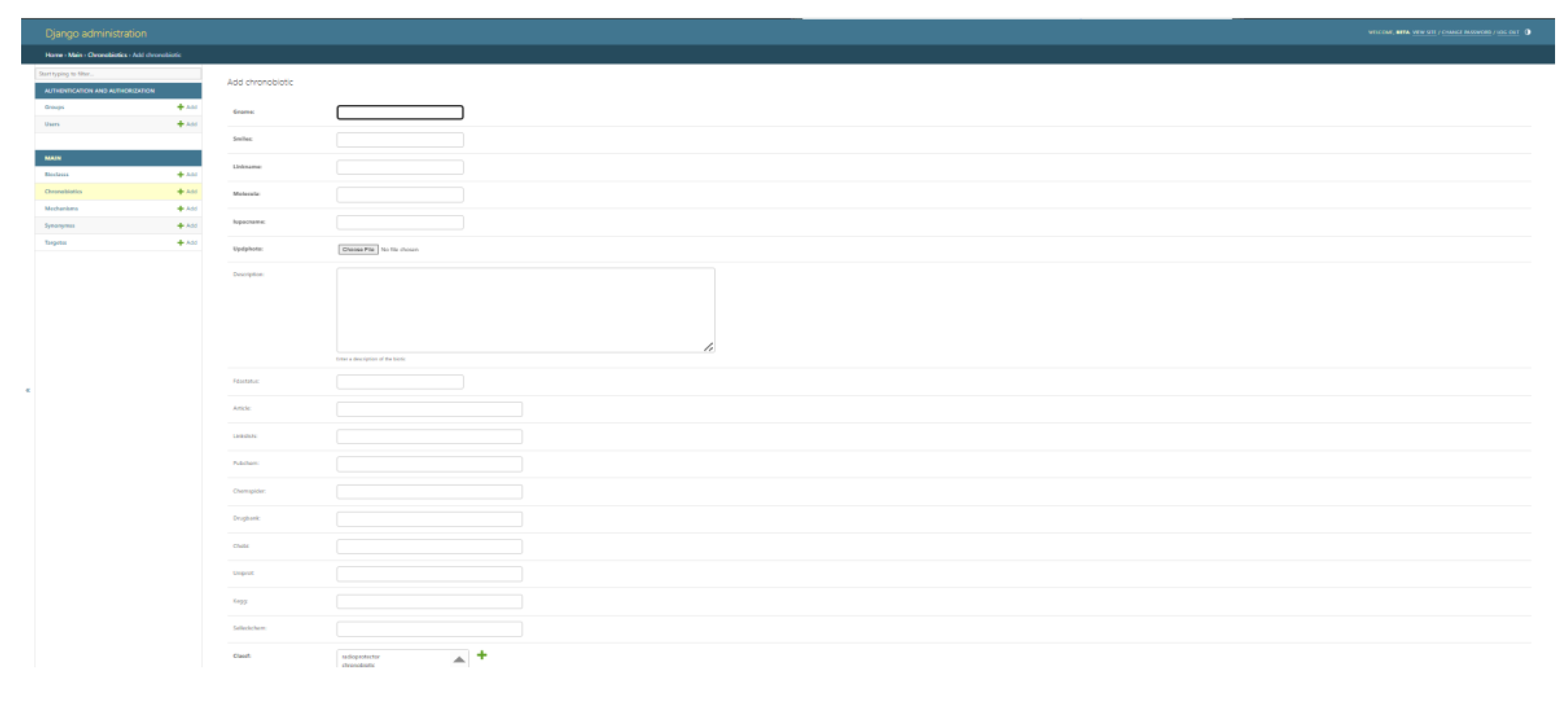

Figure 2.

The ChronobioticDB administrator back-end, illustrating the Django-powered interface for adding a new chronobiotic entry. The form (accessible only to authorized curators) provides structured fields for chemical identifiers (e.g., Name, SMILES, IUPAC name, molecular formula), descriptive information, regulatory status (FDA approval), external database IDs (PubChem, ChemSpider) (Kim and Bolton, 2024), and related references. The left sidebar lists modules for managing interconnected data tables — Bioclassifications, Chronobiotics, Mechanisms, Synonyms, and Targets — reflecting the organized relational structure of the database. The secure admin interface enables continuous curation of the database by allowing curators to manually input or update entries with high granularity. This design ensures data consistency and quality: each new chronobiotic record can be thoroughly annotated and linked to relevant mechanistic and classification data through the dedicated modules. By segregating the public and admin interfaces, ChronobioticDB streamlines the contribution process for experts while maintaining an up-to-date, reliable repository that is readily accessible to the broader community for research and reference, nevertheless theaccess windows have almost the same information with different rights.

Figure 2.

The ChronobioticDB administrator back-end, illustrating the Django-powered interface for adding a new chronobiotic entry. The form (accessible only to authorized curators) provides structured fields for chemical identifiers (e.g., Name, SMILES, IUPAC name, molecular formula), descriptive information, regulatory status (FDA approval), external database IDs (PubChem, ChemSpider) (Kim and Bolton, 2024), and related references. The left sidebar lists modules for managing interconnected data tables — Bioclassifications, Chronobiotics, Mechanisms, Synonyms, and Targets — reflecting the organized relational structure of the database. The secure admin interface enables continuous curation of the database by allowing curators to manually input or update entries with high granularity. This design ensures data consistency and quality: each new chronobiotic record can be thoroughly annotated and linked to relevant mechanistic and classification data through the dedicated modules. By segregating the public and admin interfaces, ChronobioticDB streamlines the contribution process for experts while maintaining an up-to-date, reliable repository that is readily accessible to the broader community for research and reference, nevertheless theaccess windows have almost the same information with different rights.

This section pertains to a specialized user-friendly form that any researcher engaged in the study of chronobiotics may complete accessing the directory with administration permission. This provision is applicable to both researchers who have published data on novel compounds and those who have repurposed existing registered substances for use as chronobiotics after translational research.

Co-authors contributing to the database will be afforded the opportunity to provide a comprehensive description of the compounds, including the option to present their chemical formula in SMILES format. Additionally, they will be able to supply references to other sources where the compound has been previously discussed or described. There exists the possibility of including a concise textual annotation regarding the properties of the compound within the context of chronobiology, thereby emphasizing its potential influence on biological rhythms.

It is important to note that all submissions containing information about the compounds will be subject to a moderation process. This procedure is designed to ensure the high quality and relevance of the information provided, which is of paramount importance for advancing research in this domain.

4.1. Database Statistics and Analysis

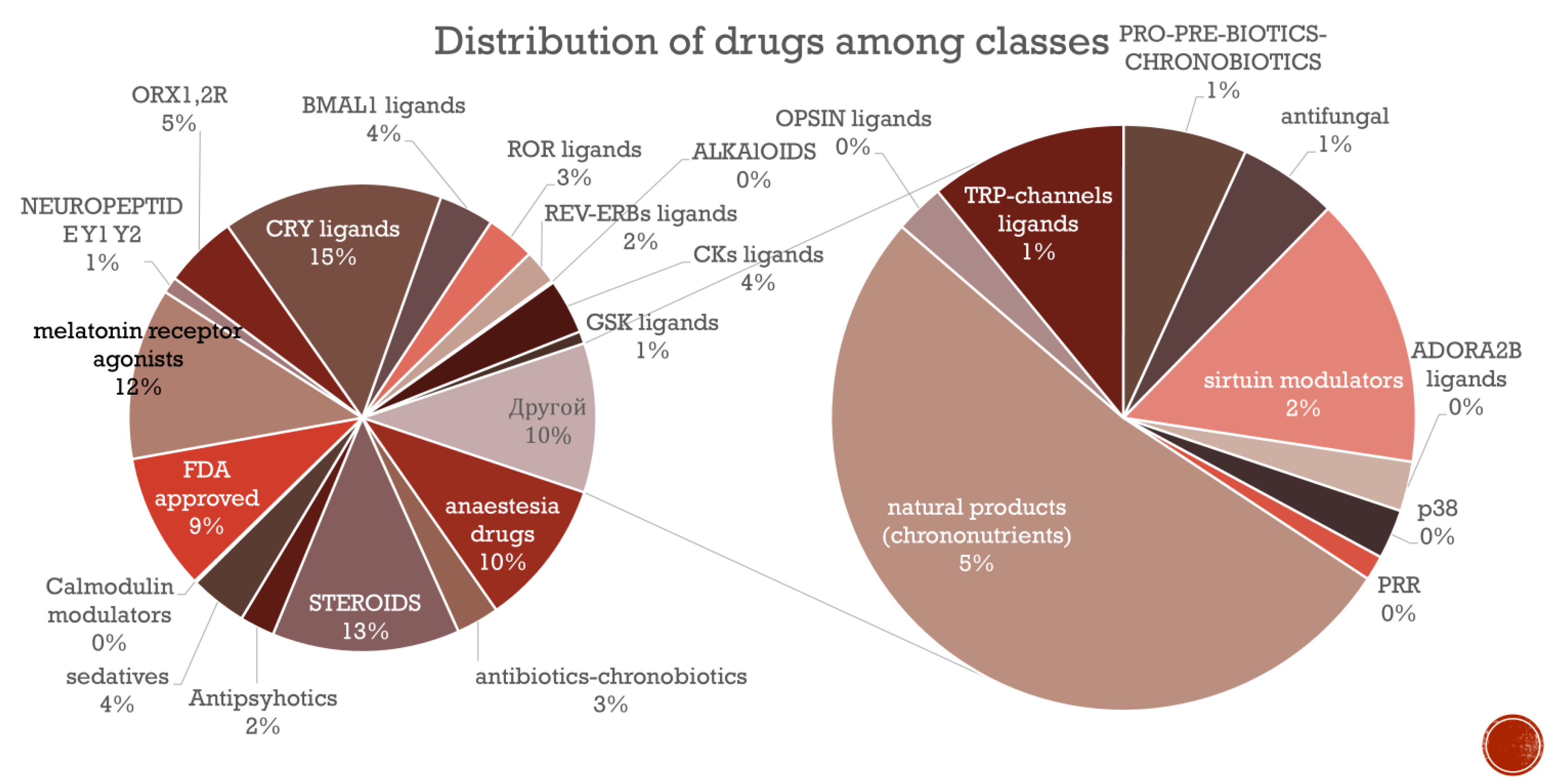

In this section we tried to analyse the percentage of different compounds in ChronobioticsDB (

Figure 3)

The pie chart illustrates the distribution of chronobiotic compounds categorized by their respective drug classes. The largest proportion of compounds (18%) are CRY ligands, followed by steroids (13%) and melatonin receptor agonists (12%). Anesthesia drugs account for 10% of the compounds, while FDA-approved drugs represent 9% (Tamai et al, 2018). Natural products, classified as chrononutrients, constitute 5%, the same proportion as ORX1,2R ligands. Antibiotics with chronobiotic properties and BMAIL1 ligands each make up 4% of the total. ROR ligands, GSK ligands, and antifungals each represent 3%. Antipsychotics, sirtuin modulators, and REV-ERBs ligands each account for 2%. Neuropeptides (EY1, Y2), PRO-PRE-BIOTICS-CHRONOBIOTICS, and other minor categories (e.g., ALKAIOIDS, OPSIN ligands, Calmodulin modulators, ADORA2B ligands, p38, PRR) each represent 1% or less, with several categories showing very small representation. This distribution highlights the diversity of chronobiotic compounds and their varying prevalence across different pharmacological classes. The structure of a relative database

The classification of molecules according to the major chemical groups

A well-structured chemical classification system is essential for organizing database, facilitating drug discovery, predicting pharmacological properties, and understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR). Compounds within the same chemical class often exhibit similar biological activity due to shared functional groups and scaffolds. Classification Enables efficient filtering as the information about class may be retrieved by AI-agents later from descriptions.

The SMILES representation of the database can be classified into various chemical classes based on their structural features and functional groups. Here's a systematic classification of ChronobioticsDB content (Imming, 2015).:

Terpenes/Steroids

Examples:

CCCCCC1=CC(=C(C(=C1)O)C2C=C(CCC2C(=C)C)C)O

CC12CCC3C(C1CCC2O)CCC4=CC(=C(C=C34)OC)O

CC(=O)C1CCC2C1(CCC3C2CC=C4C3(CCC(C4)O)C)C

Features: Multi-ring systems with hydroxyl groups and isoprene-like chains. Common in triterpenes, steroids, or sterols.

Alkaloids

Examples:

CN1CCC23C4C(=O)CCC2(C1CC5=C3C(=C(C=C5)OC)O4)O

CN1C2CCC1C(C(C2)OC(=O)C3=CC=CC=C3)C(=O)OC

Features: Nitrogen-containing heterocycles (e.g., indole, piperidine) and fused ring systems.

Sulfonamides/Sulfonates

Examples:

C1=CC=C(C=C1)S(=O)(=O)[O-]

C1=CC(=C(C=C1)Cl)Cl)CON=C(...)Cl.[N+](=O)(O)[O-]

Features: Sulfonyl groups (S(=O)₂) and aromatic rings. Common in antibiotics or diuretics.

Aromatic Compounds (Phenols, Flavonoids)

Examples:

CC1=CC(=C(C(=C1C=CC(=CC=CC(=CC(=O)O)C)C)C)OC

COC1=CC(=CC(=C1OC)OC)C2C3C(COC3=O)C(C4=CC5=C(C=C24)OCO5)O

Features: Multiple hydroxyl/methoxy groups on benzene rings, common in polyphenols or flavonoids.

Organofluorines/Organochlorines

Examples:

C(C(F)(F)F)(OC(F)F)F

C1=CC(=C(C=C1Cl)Cl)CON=C(...)Cl

Features: Trifluoromethyl (CF₃), chloro substituents. Found in pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidepressants).

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds

Examples:

C[N+](C)(C)CCOC(=O)CCC(=O)OCC[N+](C)(C)C

Features: Positively charged nitrogen with alkyl chains. Used as surfactants or disinfectants.

Amides/Peptides

Examples:

CCC(=O)N(C1CCN(CC1)CCC2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3

CC(=O)N(C1=CC=CC=C1)C2(CCN(CC2)CCC3=CC=CS3)COC

Features: NC=O groups, common in pharmaceuticals (e.g., β-lactams).

Esters/Lipids

Examples:

CCCCCCCCCC(=O)O

CCOC(=O)C1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)OCCCC

Features: Ester linkages (COO), long alkyl chains. Found in fatty acid esters.

Heterocycles (Pyridine, Thiophene)

Examples:

C1=CN(C(=O)N=C1N)CC(CO)OCP(=O)(O)O

C1=CC(=C2C(=C1NCCNCCO)C(=O)C3=C(C=CC(=C3C2=O)O)O)NCCNCCO

Features: Nitrogen/sulfur-containing rings (e.g., pyridine, thiophene).

Nitro Compounds

Examples:

C1=CC(=CC=C1C=CC2=CC(=CC(=C2)O)O)O

Features: NO₂ groups. Used in explosives or dyes.

Phosphates/Nucleotides

Examples:

C1=CN(C(=O)N=C1N)CC(CO)OCP(=O)(O)O

Features: Phosphate groups (PO₄³⁻). Found in nucleotides (e.g., ATP).

Organometallics/Salts

Examples:

[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[As+3].[As+3] (Arsenate salt)

C(=O)(C(F)(F)F)O (Trifluoroacetate salt)

Features: Metal ions or ionic groups (e.g., [Na+]).

Macrocyclic Compounds

Examples:

CC12CCC(=O)C=C1C3CC3C4C2CCC5(C4C6CC6C57CCC(=O)O7)C

Features: Large rings (12+ atoms). Seen in macrolide antibiotics.

Disulfides

Examples:

C(C(=O)NC(...)CSSCC(...)

Features: S-S bonds. Common in peptides (e.g., insulin).

Alkyne Derivatives

Examples:

CCC#CC(C)C1(C(=O)NC(=O)N(C1=O)C)CC=C

Features: Triple bonds (C#C). Used in click chemistry.

Barbiturates

Examples:

CCC(=O)NC(=O)NC1=O

Features: Pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione core. Sedative/hypnotic agents.

Key observations on the proposed classes in ChronobioticsDB

Terpenes/Steroids are highly lipophilic, often interacting with membrane-bound receptors (e.g., steroid hormones). Subclassification useful for pharcmacology (e.g., triterpenes vs. steroids, saponins vs. cardiac glycosides). Alkaloids have basic nitrogen atoms influencing pharmacokinetics (e.g., blood-brain barrier penetration). Subclasses (indoles, tropanes, isoquinolines) may correlate with specific bioactivities. Sulfonamides/Sulfonates are the key in antibacterials (sulfa drugs) and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, noteworthy these drugs may trigger hypersensitivity reactions in some patients. Organohalogens often have enhanced metabolic stability (e.g., fluoxetine, haloperidol). Chlorinated aromatics may raise toxicity concerns (e.g., bioaccumulation). Quaternary ammonium compounds have permanent positive charge limits absorption but enhances antimicrobial activity. Macrocyclic Compounds have constrained structures improving target binding (e.g., cyclosporine, macrolide antibiotics).

Some drugs in ChronobioticsDB belong to multiple categories (e.g., alkaloids with terpene moieties). Hybrid classifications may be needed. New synthetic chemotypes (e.g., PROTACs, covalent inhibitors) may require additional classes and it is the dominating problem of this approach to content classification, the vast group of circadian rhythms modulators have the same targets and totally different chemical classifications.

Practical Implementation in a Database may be based on Hierarchical Taxonomy: Broad classes (e.g., "Alkaloids") → subclasses (e.g., "Indole Alkaloids"), SMILES-Based Queries like automatic classification using structural fingerprints which will be incorporated in later versions. The classification will later help in broad activity annotations literally link chemical classes to typical therapeutic uses (e.g., Barbiturates → Sedatives).

A chemically informed classification system enhances drug database utility by enabling structure-based searches, SAR analysis, and predictive modeling. Future refinements could incorporate machine learning SAR/QSAR models for automated class assignment based on emerging chemotypes.

5. Discussion

The development of «ChronobioticsDB» represents a significant advancement for chronobiology, pharmacoinformatics, and bioinformatics, as at the present day only circadian gene expression databases exist (Pizarro, et al 2012; Zhu et al., 2024). Collecting together critical data on compounds that modulate circadian rhythms, this database addresses a longstanding gap in the scientific community’s ability to systematically study and apply chronobiotics. Through a balanced combination of primary data—manually curated and verified—and secondary data drawn from sources like PubChem, DrugBank (Knox et al., 2024), and ChemSpider (Pence and Williams, 2010)., «ChronobioticsDB» not only functions as a repository but also evolves into a dynamic tool for researchers and clinicians.

A core challenge in chronobiology has been the absence of a unified framework for classifying chronobiotic compounds; historically, researchers have had to rely on fragmented resources defined by chemical properties, mechanisms of action, or therapeutic applications. By establishing a relational database structure and organizing compounds according to their chemical, pharmacological, and biological characteristics, «ChronobioticsDB» enables researchers to detect patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed and to discover entirely new chronobiotics. The use of SMILES notation for chemical structures and the integration of data from multiple sources—ranging from FDA approval statuses to clinical trial results—further bridge the gap between basic research and clinical applications , facilitating the exploration of molecular mechanisms underlying circadian rhythms. This broad view is especially relevant to chronomedicine and therapeutics, as circadian disruption is increasingly linked to metabolic syndromes, neurodegenerative conditions, and mood disorders; by classifying compounds into groups such as CRY ligands, melatonin receptor agonists, and steroids, the database provides a crucial resource for focusing on targeted interventions.

Moreover, synchronizing compound profiles with clinical trial data reveals insights into the safety and efficacy of chronobiotic therapies, helping refine existing treatments or guide new ones. Despite these innovations, «ChronobioticsDB» faces important challenges, notably the need for perpetual updates as new findings emerge and the desirability of integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to achieve a richer, system-level view of how these compounds operate on circadian pathways. Adding visualization and analytics tools, such as network mapping or predictive modeling, could further illuminate interactions among compounds, targets, and biological processes, promoting deeper hypothesis generation and testing.

Finally, ethical and practical considerations mandate close attention to intellectual property rights and data security: providing precise citations helps ensure proper attribution, while role-based access and encryption maintain the confidentiality and integrity of the database’s contents. By harmonizing these elements, «ChronobioticsDB» stands poised to guide both foundational chronobiology and clinical innovation, offering a unifying, data-driven platform for the scientific community’s ongoing exploration of circadian rhythm modulation.

6. Conclusions

«ChronobioticsDB» represents a pioneering effort to consolidate and organize knowledge on compounds that modulate circadian rhythms. By addressing the fragmentation in chronobiotic research, bridging the gap between chronobiology and bioinformatics, and providing a platform for translational research, this database has the potential to significantly advance our understanding of circadian rhythms and their therapeutic applications. As the field continues to evolve, «ChronobioticsDB» will serve as a valuable resource for researchers, clinicians, and drug developers, ultimately contributing to the development of novel therapies for circadian-related disorders. Future efforts to expand and enhance the database will further solidify its role as a cornerstone of chronobiological research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S., D.G. and A.Y.; methodology, I.S., N.K. and A.Y.; software, N.K. and A.Y.; validation, I.S., D.G.; formal analysis I.S., D.G; investigation, I.S. and D.G.; resources, N.K. and A.Y.; data curation, I.S. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation I.S. and D.G., A.Y.; writing—review and editing, I.S. and N.K.; visualisation, A.Y. and I.S.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation Grant “Design of the world's first pharmacological database of circadian rhythm modulators (ChronobioticsDB) and organisation of the access to it” (Project no. 24-75-00108).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The database is dedicated to the memory of outstanding scientists: academician of Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), V. H. Havinson; corresponding member of RAS, V. N. Anisimov, and professor G. D. Gubin who stood at the origins of Soviet and Russian chronomedicine and chronogerontology. The authors would like to thank the Department of Applied mathematics (Pitirim Sorokin Syktyvkar State University) for technical consultations and RSF for funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bittrich, S., Segura, J., Duarte, J.M., Burley, S.K. and Rose, Y., 2024. RCSB protein Data Bank: exploring protein 3D similarities via comprehensive structural alignments. Bioinformatics, 40(6), p.btae370.

- Califf, R.M., Cutler, T.L., Marston, H.D. and Meeker-O’Connell, A., 2025. The importance of ClinicalTrials. gov in informing trial design, conduct, and results. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 9(1), p.e42.

- Cha, H.K., Chung, S., Lim, H.Y., Jung, J.W. and Son, G.H., 2019. Small molecule modulators of the circadian molecular clock with implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience, 11, p.496.

- Chen, Z., Yoo, S.H. and Takahashi, J.S., 2018. Development and therapeutic potential of small-molecule modulators of circadian systems. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 58(1), pp.231-252.

- Holovaty, A. Holovaty, A. and Willison, S., 2003. Django web framework. Available online: http://www. djangoproject. Com.

- Imming, P., 2015. Medicinal chemistry: Definitions and objectives, drug activity phases, drug classification systems. In The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry (pp. 3-13). Academic Press.

- Kim, S. and Bolton, E.E., 2024. PubChem: A Large-Scale Public Chemical Database for Drug Discovery. Open Access Databases and Datasets for Drug Discovery, pp.39-66.

- Knox, C. Knox, C., Wilson, M., Klinger, C.M., Franklin, M., Oler, E., Wilson, A., Pon, A., Cox, J., Chin, N.E., Strawbridge, S.A. and Garcia-Patino, M., 2024. DrugBank 6.0: the DrugBank knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic acids research, 52(D1), pp.D1265-D1275.

- Odell, S.G., Lazo, G.R., Woodhouse, M.R., Hane, D.L. and Sen, T.Z., 2017. The art of curation at a biological database: principles and application. Current Plant Biology, 11, pp.2-11.

- Pence, H.E. and Williams, A., 2010. ChemSpider: an online chemical information resource.

- Pizarro, A., Hayer, K., Lahens, N.F. and Hogenesch, J.B., 2012. CircaDB: a database of mammalian circadian gene expression profiles. Nucleic acids research, 41(D1), pp.D1009-D1013.

- Robles-Piedras, A.L., Bautista-Sánchez, U., Olvera-Hernández, E.G. and Chehue-Romero, A., 2024. Chronopharmacokinetics: A Brief Analysis of the Influence of Circadian Rhythm on the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination of Drugs. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 17(3), pp.2011-2017.

- Simkovics, S. and Petersgasse, P., 1998. Enhancement of the ANSI SQL Implementation of PostgreSQL.

- Solovev, I.A. and Golubev, D.A., 2024. Chronobiotics: classifications of existing circadian clock modulators, future perspectives. Biomeditsinskaya khimiya, 70(6), pp.381-393.

- Tamai, T.K., Nakane, Y., Ota, W., Kobayashi, A., Ishiguro, M., Kadofusa, N., Ikegami, K., Yagita, K., Shigeyoshi, Y., Sudo, M. and Nishiwaki-Ohkawa, T., 2018. Identification of circadian clock modulators from existing drugs. EMBO molecular medicine, 10(5), p.e8724.

- Zhu, X., Han, X., Li, Z., Zhou, X., Yoo, S.H., Chen, Z. and Ji, Z., 2025. CircaKB: a comprehensive knowledgebase of circadian genes across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Research, 53(D1), pp.D67-D78.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).