Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vineyard Characteristics and Winemaking Trials

2.2. Grapes Analysis and Basic Parameters of Wines

2.3. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Analyses of Anthocyanins

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

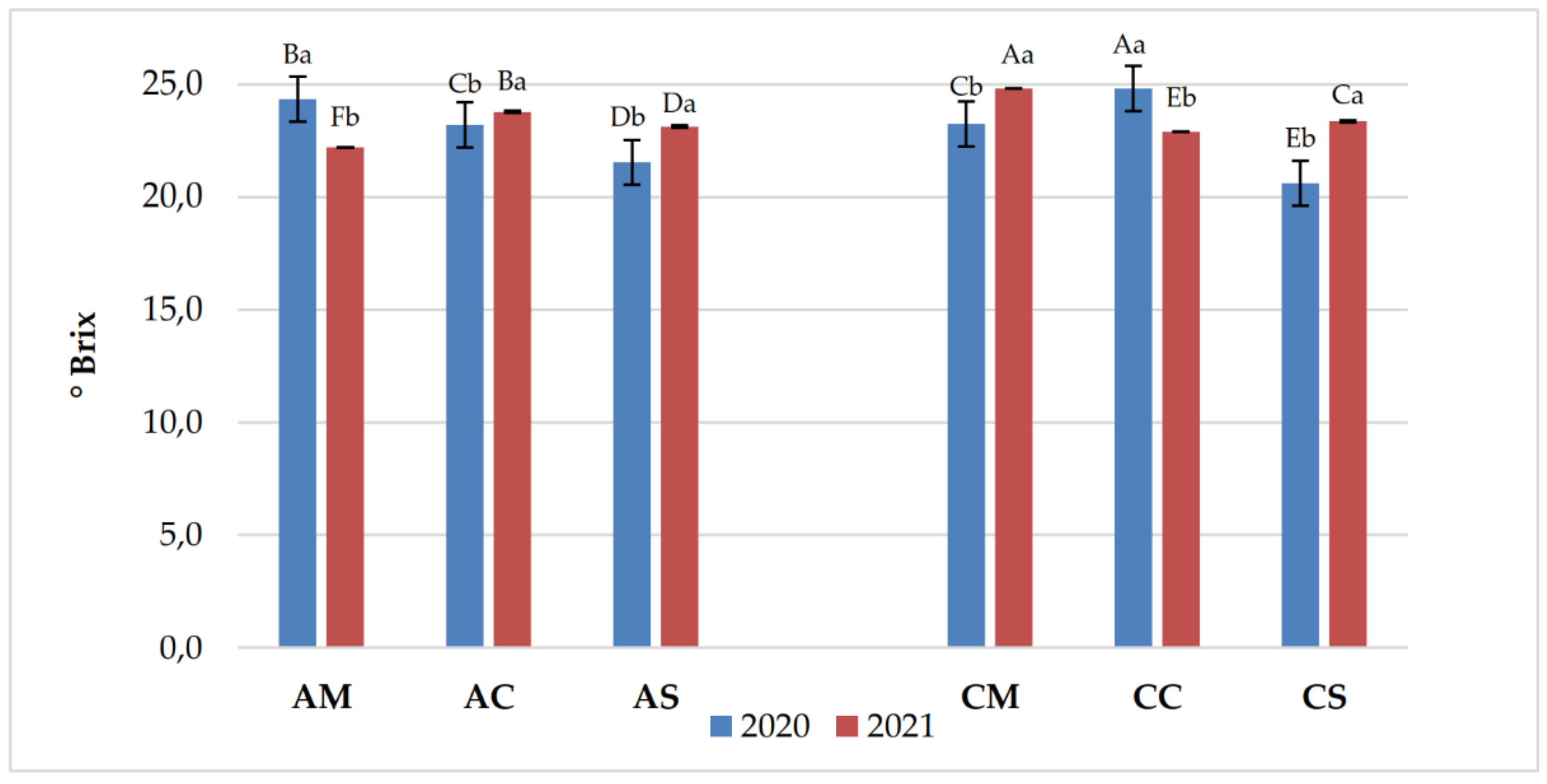

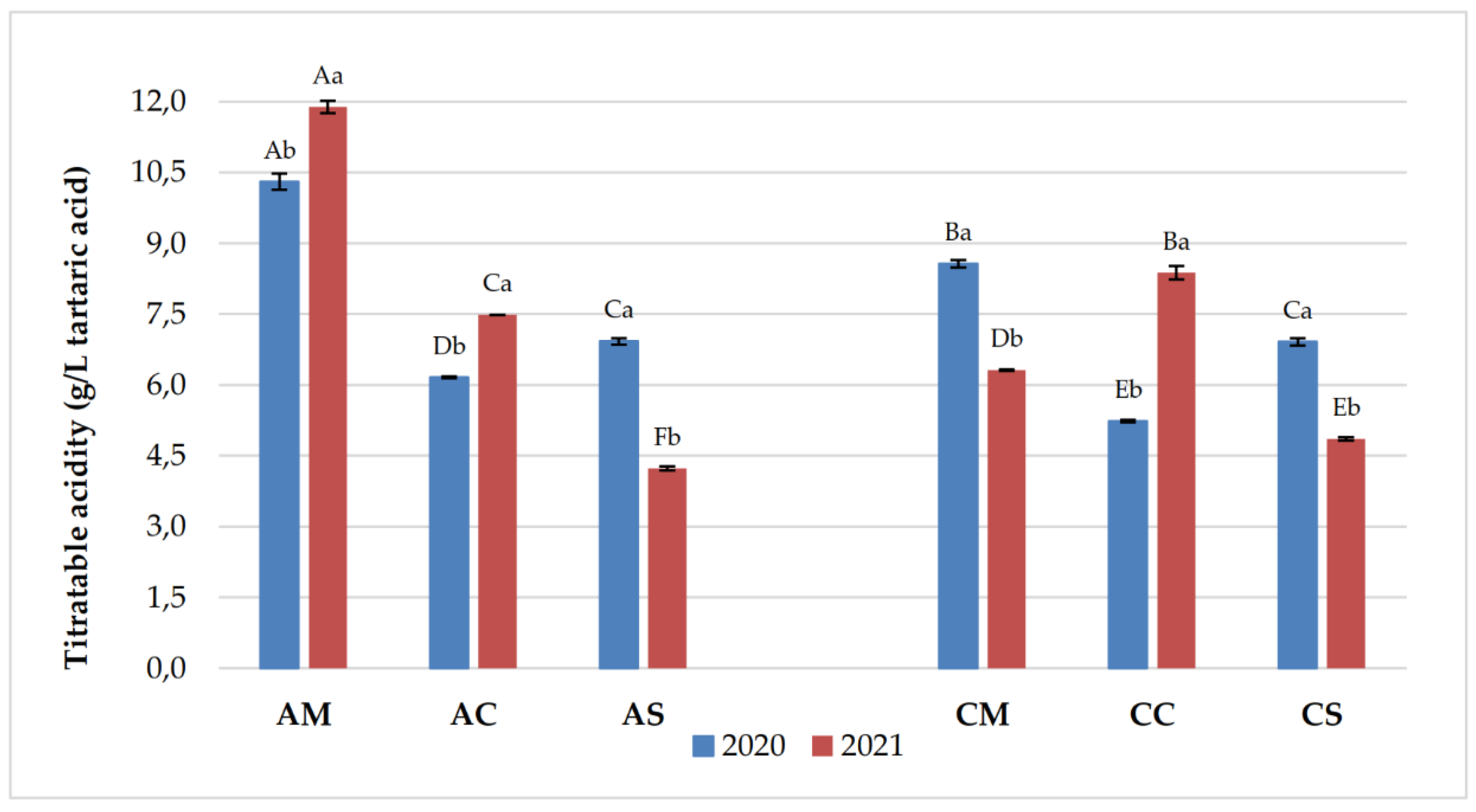

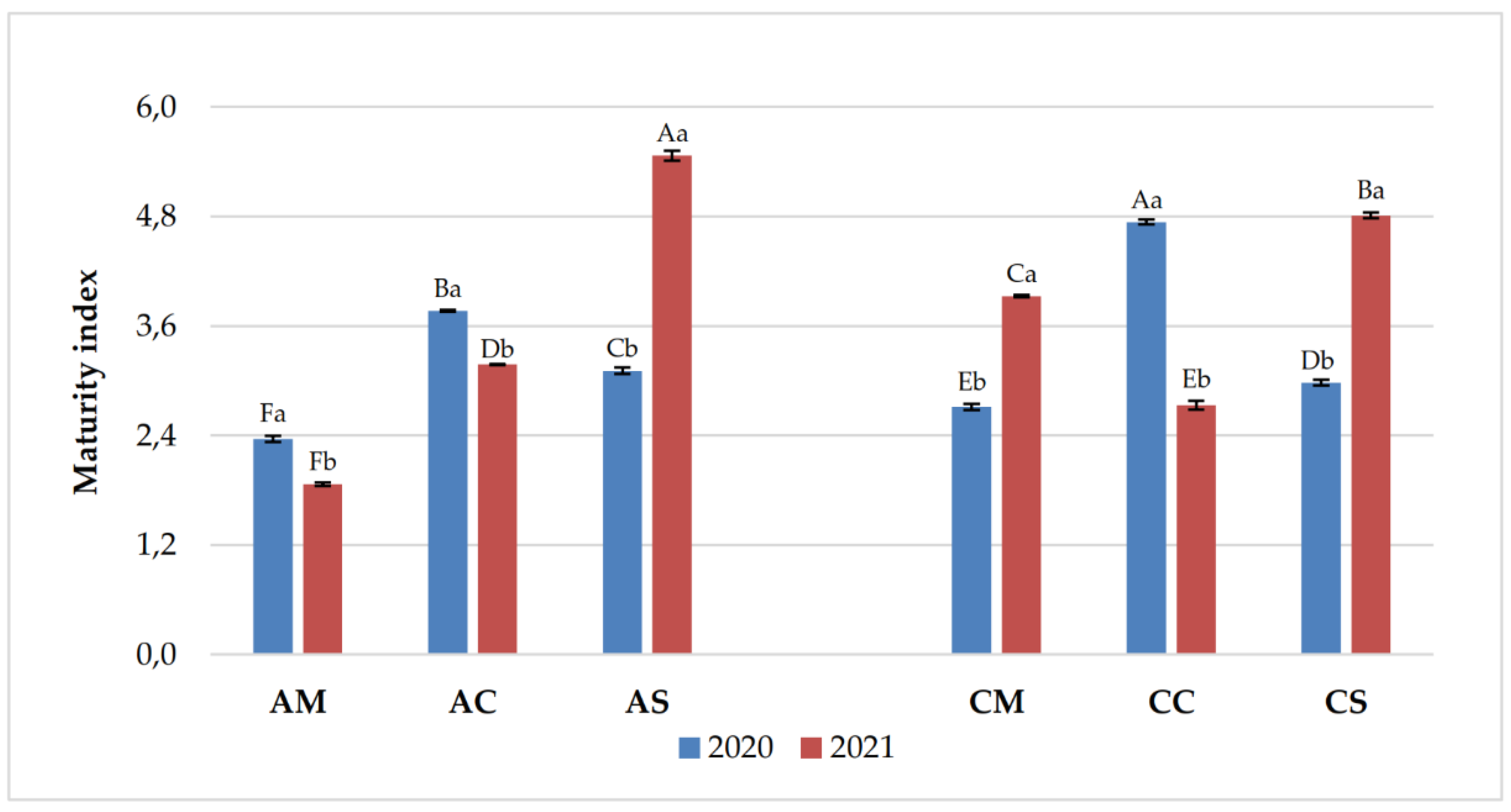

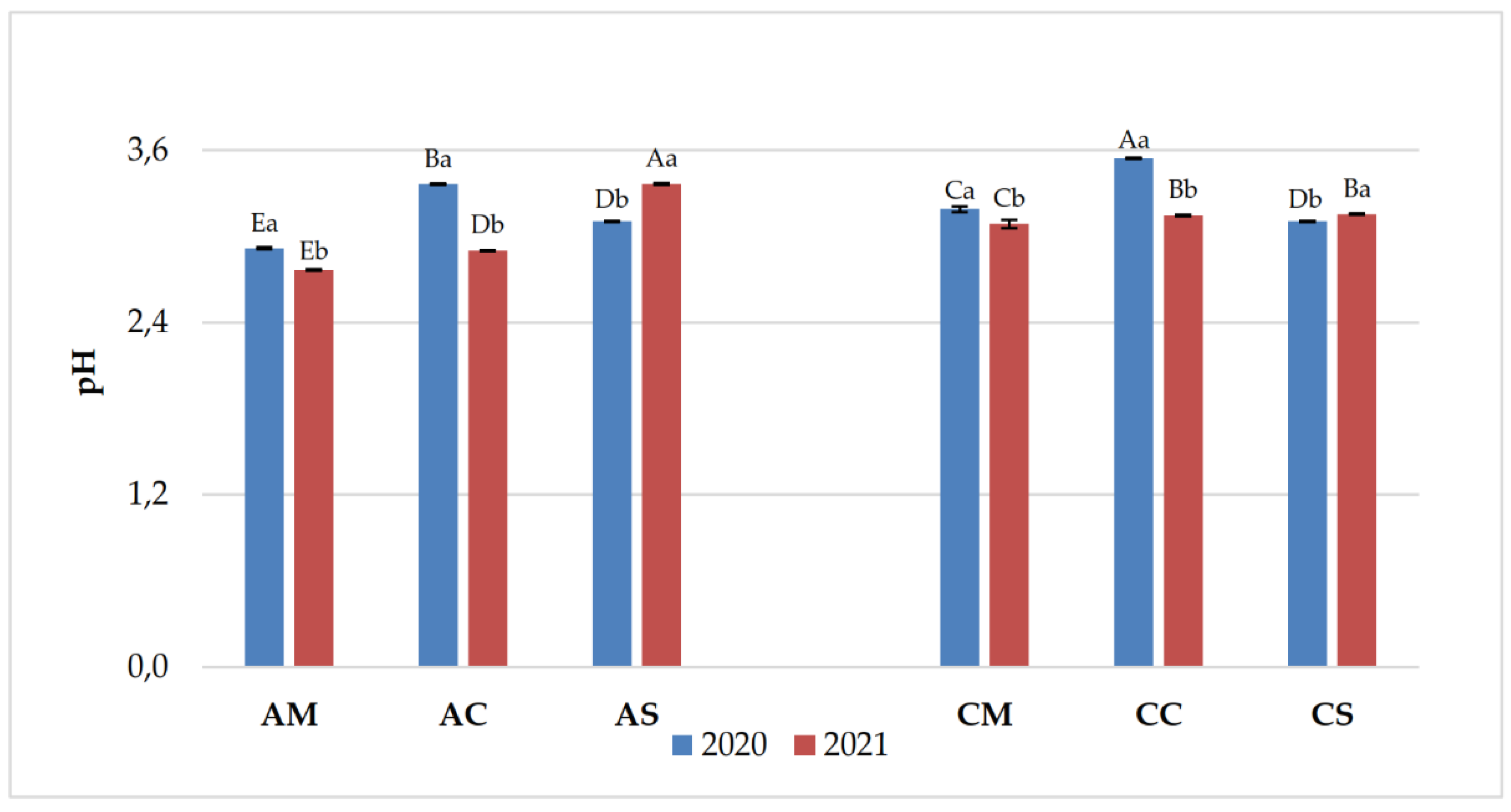

3.1. Chemical Parameters in Grapes and Wines

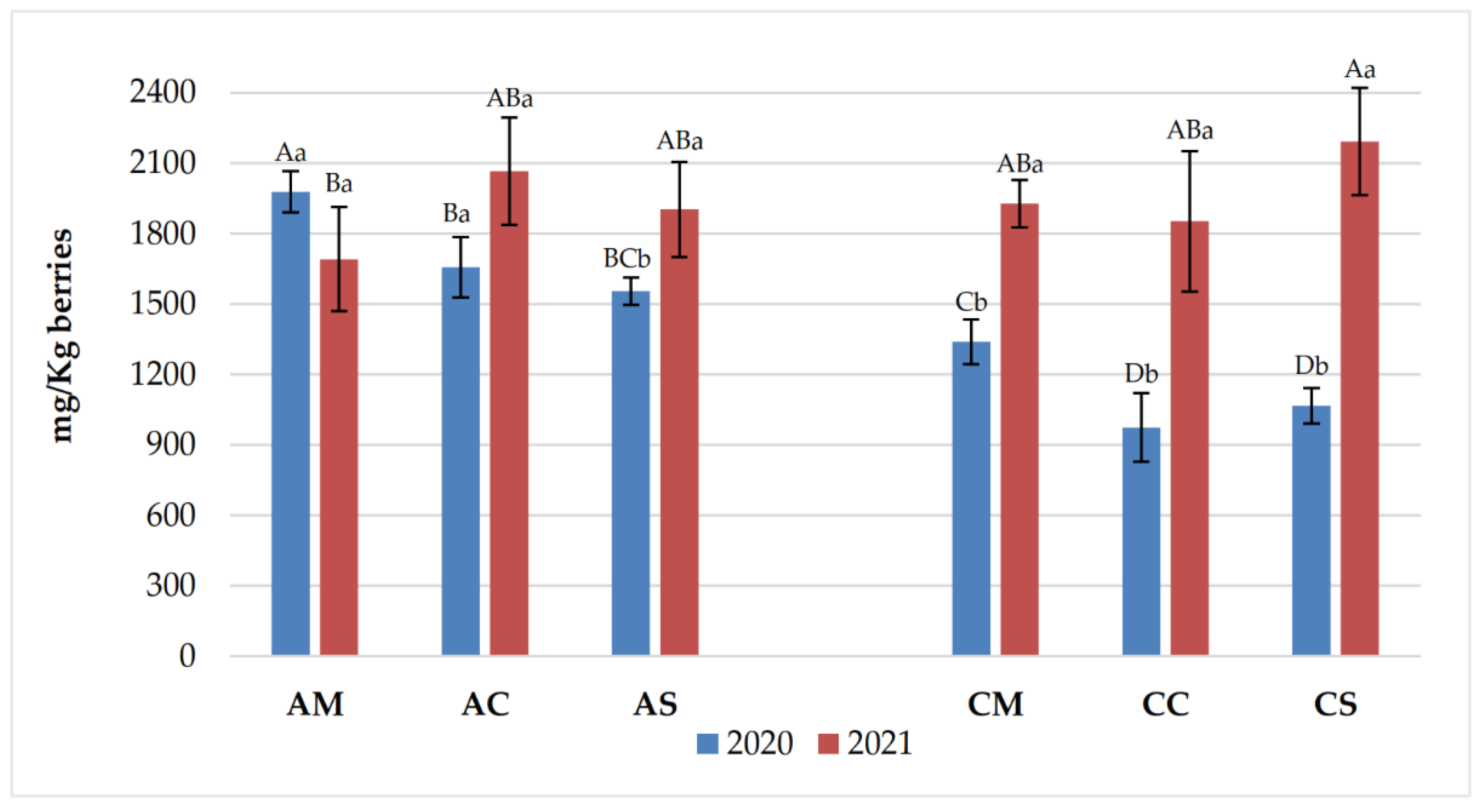

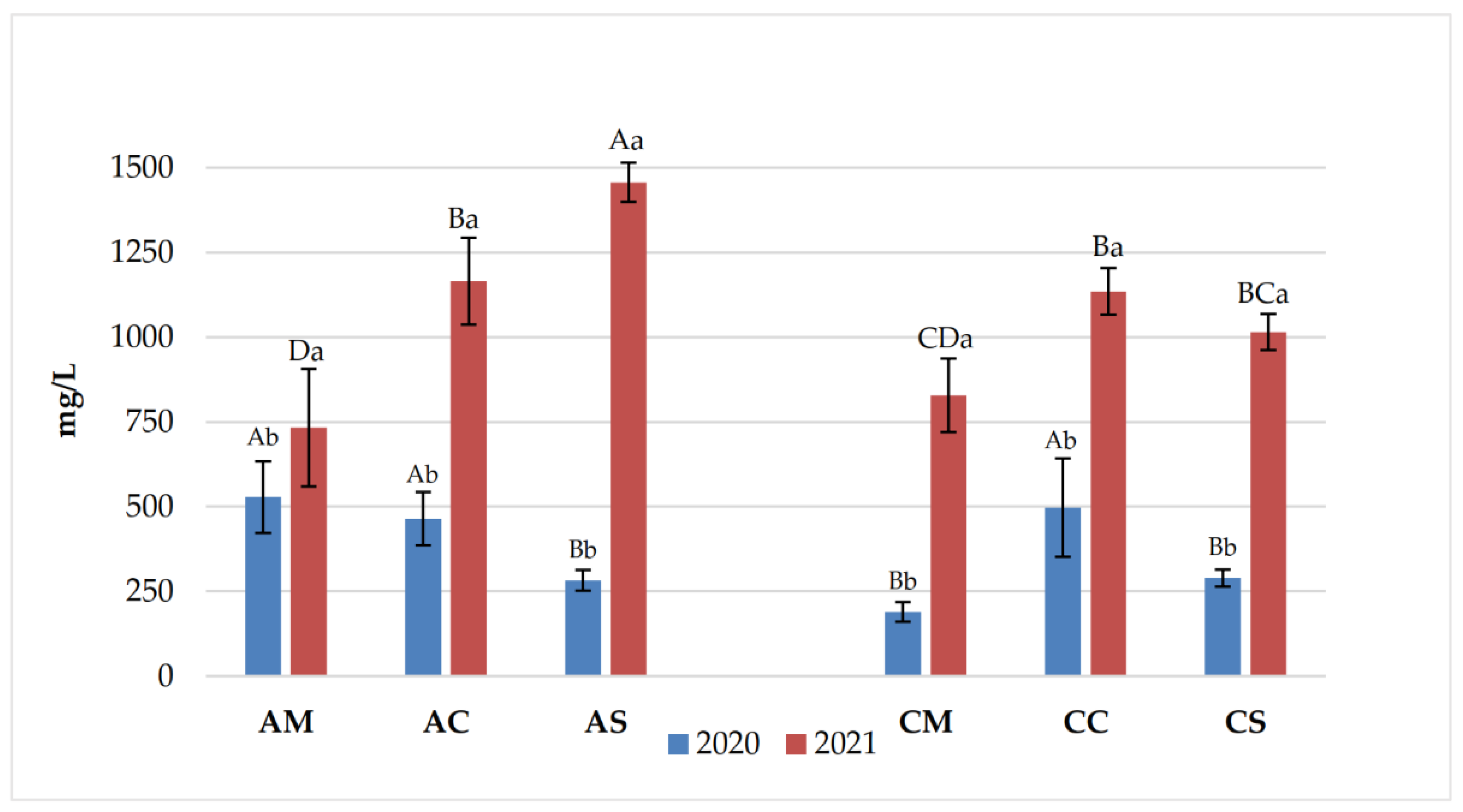

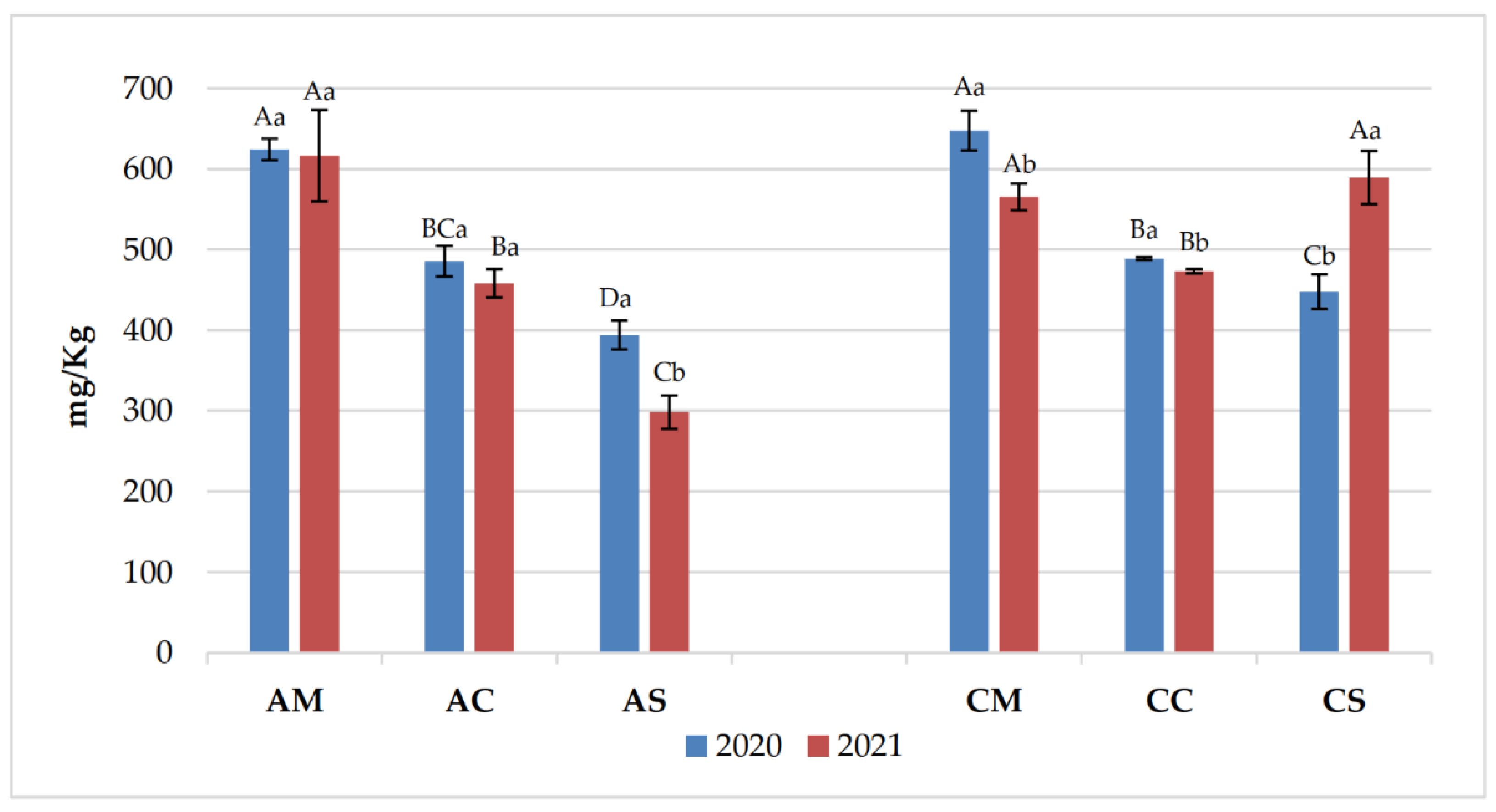

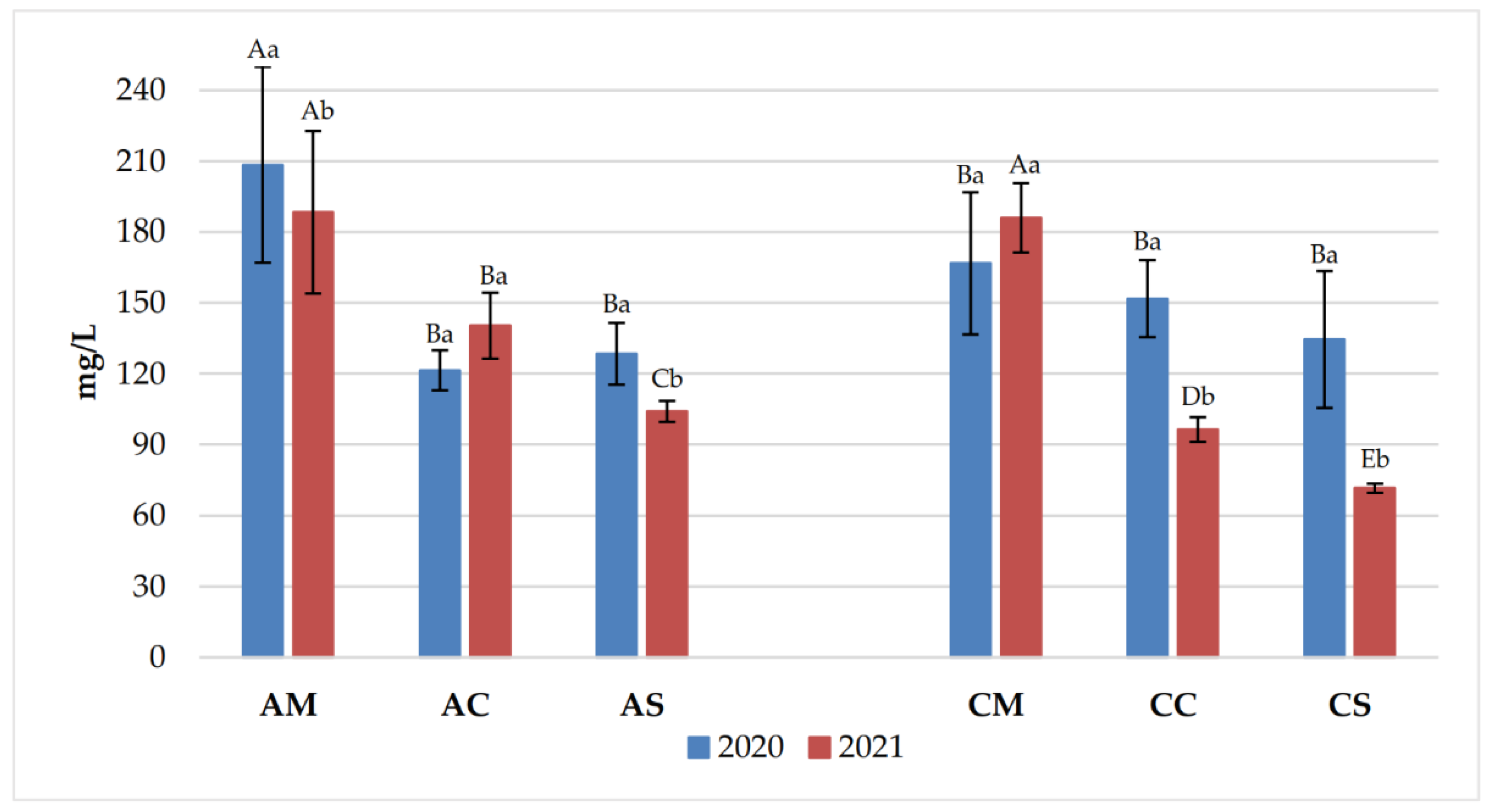

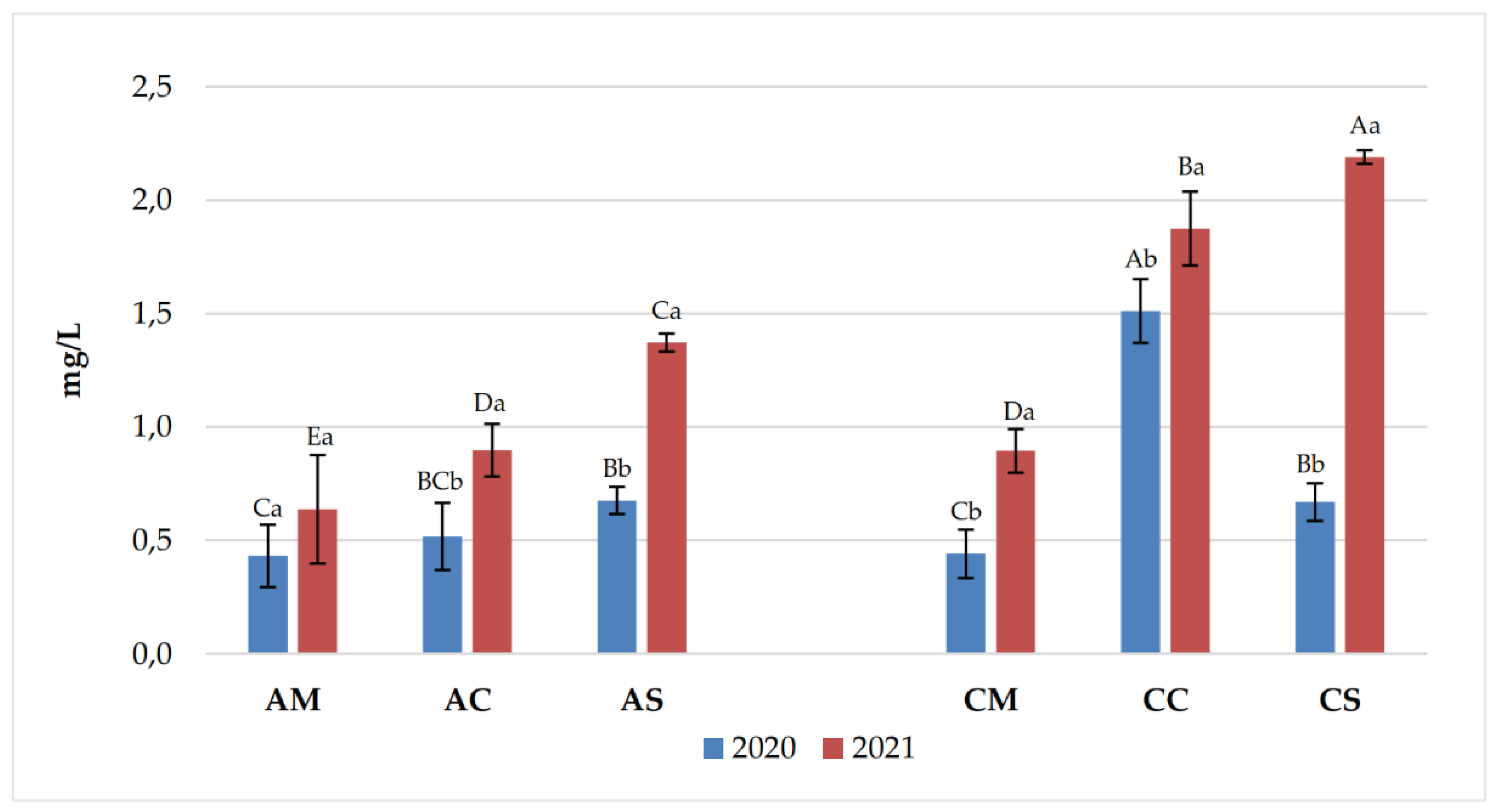

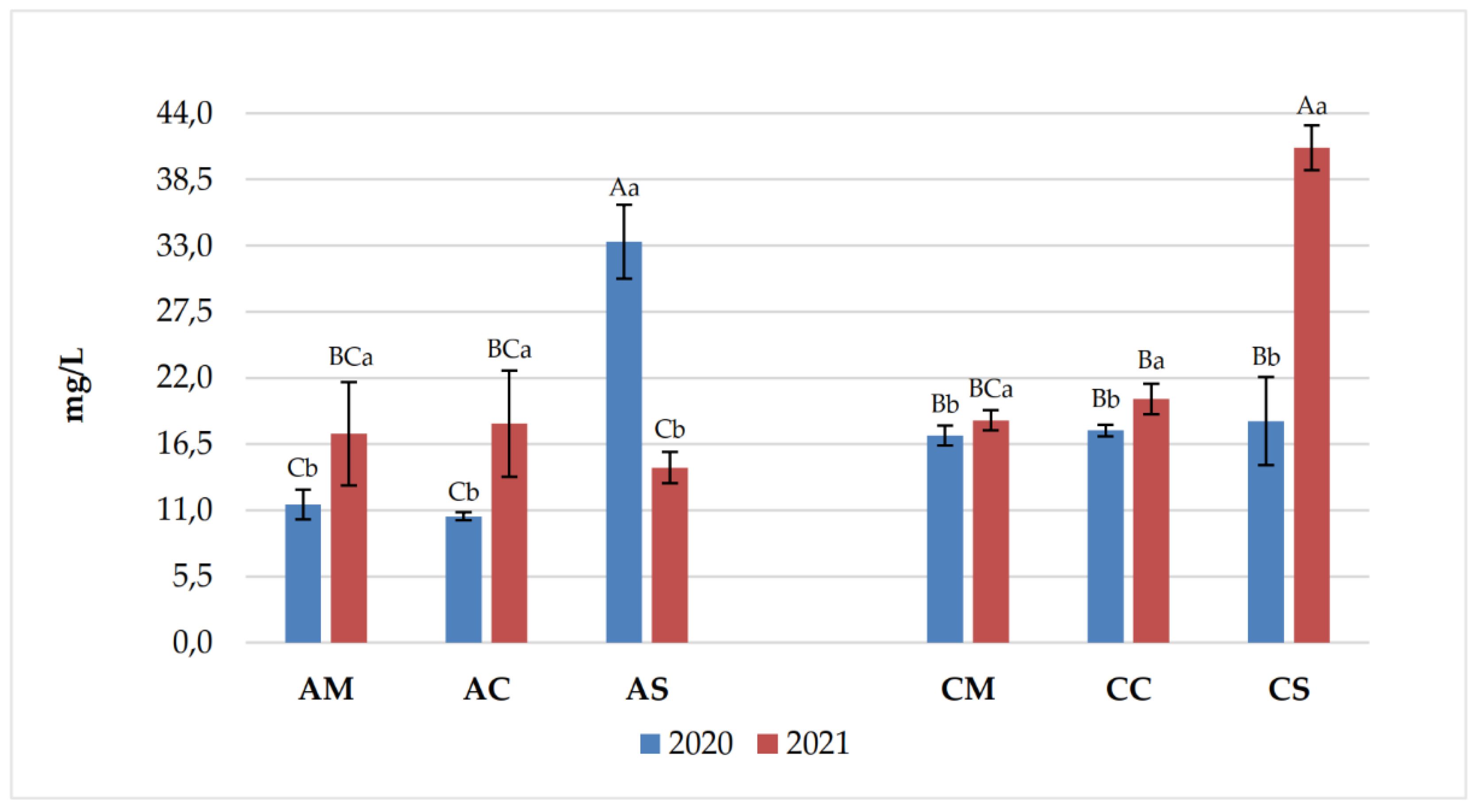

3.2. Polyphenolic Content of Grapes and Wines

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iorizzo, M.; Sicilia, A.; Nicolosi, E.; Forino, M.; Picariello, L.; Lo Piero, A.R.; Vitale, A.; Monaco, E.; Ferlito, F.; Succi, M.; et al. Investigating the Impact of Pedoclimatic Conditions on the Oenological Performance of Two Red Cultivars Grown throughout Southern Italy. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1250208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Bagnoli, D.; Vergalito, F.; Testa, B.; Tremonte, P.; Succi, M.; Pannella, G.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Lombardi, S.J.; et al. Diversity of Fungal Communities on Cabernet and Aglianico Grapes from Vineyards Located in Southern Italy. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, G.; Ghanem, C.; Mercenaro, L.; Nassif, N.; Hassoun, G.; Caro, A.D. Effects of Altitude on the Chemical Composition of Grapes and Wine: A Review. OENO One 2022, 56, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, A.; Brillante, L. Terroir Analysis and Its Complexity: This Article Is Published in Cooperation with Terclim 2022 (XIVth International Terroir Congress and 2nd ClimWine Symposium), 3-8 July 2022, Bordeaux, France. OENO One 2022, 56, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Iorizzo, M.; Di Renzo, M.; Coppola, R.; Succi, M. Preliminary Characterisation of Metschnikowia pulcherrima to Be Used as a Starter Culture in Red Winemaking. Beverages 2024, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Karaulli, J.; Ruci, M.; Pistillo, M.; Germinara, G.S.; Messia, M.C.; Succi, M.; et al. Versatility of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 41CM in the Brewery Sector: Use as a Starter for “Ale” and “Lager” Craft Beer Production. Processes 2022, 10, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaulli, J.; Xhaferaj, N.; Coppola, F.; Testa, B.; Letizia, F.; Kyçyk, O.; Kongoli, R.; Ruci, M.; Lamçe, F.; Sulaj, K.; et al. Bioprospecting of Metschnikowia pulcherrima Strains, Isolated from a Vineyard Ecosystem, as Novel Starter Cultures for Craft Beer Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Definition of Vitivinicultural “Terroir” | OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/node/3362 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Bonfante, A.; Monaco, E.; Langella, G.; Mercogliano, P.; Bucchignani, E.; Manna, P.; Terribile, F. A Dynamic Viticultural Zoning to Explore the Resilience of Terroir Concept under Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C. 9 - Terroir: The Effect of the Physical Environment on Vine Growth, Grape Ripening, and Wine Sensory Attributes. In Managing Wine Quality (Second Edition); Reynolds, A.G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2022; pp. 341–393 ISBN 978-0-08-102067-8.

- Cameron, B. Phenology and Terroir Heard Through the Grapevine. In; 2025; pp. 573–593 ISBN 978-3-031-75026-7.

- Rouxinol, M.I.; Martins, M.R.; Barroso, J.M.; Rato, A.E. Wine Grapes Ripening: A Review on Climate Effect and Analytical Approach to Increase Wine Quality. Appl. Biosci. 2023, 2, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine Polyphenol Content and Its Influence on Wine Quality and Properties: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Silva, V.; Igrejas, G.; Aires, A.; Falco, V.; Valentão, P.; Poeta, P. Phenolic Compounds Classification and Their Distribution in Winemaking By-Products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-C.; Han, X.; Tian, M.-B.; Shi, N.; Li, M.-Y.; Duan, C.-Q.; He, F.; Wang, J. Integrated Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Insights into How Macro-Terroir Affects Polyphenols of Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 341, 113996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheynier, V.V.; Duenas-Paton, M.; Salas, E.; Maury, C.; Souquet, J.M.J.M.; Manchado-Sarni, P.; Fulcrand, H. Structure and Properties of Wine Pigments and Tannins. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rayess, Y.; Nehme, N.; Azzi-Achkouty, S.; Julien, S.G. Wine Phenolic Compounds: Chemistry, Functionality and Health Benefits. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2021, 27, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Succi, M.; Iorizzo, M. Biotechnological Strategies for Ethanol Reduction in Wine. Fermentation 2025, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Lu, S. Biosynthesis and Regulation of Phenylpropanoids in Plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Vigneron, N.; Darriet, P.; Sweetman, C.; Burbidge, C.; Bonghi, C.; Walker, R.P.; Famiani, F.; Castellarin, S.D. Grape Berry Secondary Metabolites and Their Modulation by Abiotic Factors in a Climate Change Scenario–A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, R.; Pajovic Scepanovic, R.; Raicevic, D.; Popović, T.; Korntheuer, K.; Wendelin, S.; Forneck, A.; Philipp, C. Study of the Effects of Climatic Conditions on the Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Austrian and Montenegrin Red Wines. OENO One 2023, 57, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Vilela, A.; Moreira, L.; Moura, C.; Enríquez, J.A.P.; Filipe-Ribeiro, L.; Nunes, F.M. Terroir Effect on the Phenolic Composition and Chromatic Characteristics of Mencía/Jaen Monovarietal Wines: Bierzo D.O. (Spain) and Dão D.O. (Portugal). Molecules 2020, 25, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Cosme, F.; Rivero-Perez, M.; Jordão, A.; González-SanJosé, M.L. Influence of Wine Region Provenance on Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Radical Scavenger Activity of Traditional Portuguese Red Grape Varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.-R.; He, F.; Xiao, H.-L.; Duan, C.-Q.; Pan, Q.-H. Accumulation Pattern of Flavonoids in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes Grown in a Low-Latitude and High-Altitude Region. S. Afr. j. enol. vitic. 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, C. Survey of the Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Properties of Wines from Five Regions of China According to Variety and Vintage. LWT 2022, 169, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkytė, V.; Longo, E.; Windisch, G.; Boselli, E. Phenolic Compounds as Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity. Foods 2020, 9, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urvieta, R.; Buscema, F.; Bottini, R.; Coste, B.; Fontana, A. Phenolic and Sensory Profiles Discriminate Geographical Indications for Malbec Wines from Different Regions of Mendoza, Argentina. Food Chem. 2018, 265, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumšta, M.; Pavloušek, P.; Kárník, P. Use of Anthocyanin Profiles When Differentiating Individual Varietal Wines and Terroirs. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 52, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, F.; Nicolosi, E.; Sicilia, A.; Villano, C.; Aversano, R.; Lo Piero, A.R. Physiological and Productive Responses of Two Vitis Vinifera L. Cultivars across Three Sites in Central-South Italy. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, A.; Villano, C.; Aversano, R.; Di Serio, E.; Nicolosi, E.; Ferlito, F.; Lo Piero, A.R. Study of Red Vine Phenotypic Plasticity across Central-Southern Italy Sites: An Integrated Analysis of the Transcriptome and Weather Indices through WGCNA. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH Monograph. 2018. [CrossRef]

- LORENZ, D.H.; EICHHORN, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; KLOSE, R.; MEIER, U.; WEBER, E. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Phenological Growth Stages of the Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L. Ssp. Vinifera)? Codes and Descriptions According to the Extended BBCH Scale? Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2008, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis | OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Gambuti, A.; Han, G.; Peterson, A.L.; Waterhouse, A.L. Sulfur Dioxide and Glutathione Alter the Outcome of Microoxygenation. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbertson, J.; Picciotto, E.; Adams, D. Measurement of Polymeric Pigments in Grape Berry Extracts and Wines Using a Protein Precipitation Assay Combined with Bisulfite Bleaching. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, F.; Zulian, C.; Nicolini, G.; Valenti, L. Wine, Biodiversity, Technology, and Antioxidants. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 957, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadras, V. o.; Petrie, P. r. Climate Shifts in South-Eastern Australia: Early Maturity of Chardonnay, Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon Is Associated with Early Onset Rather than Faster Ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2011, 17, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, D.; Weedon, M. Temperature-Dependent Responses of the Berry Developmental Processes of Three Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera) Cultivars. New. Zeal. J. Crop. Hort. 2014, 42, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gli indicatori del clima in Italia nel 2021 – Anno XVII. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/stato-dellambiente/gli-indicatori-del-clima-in-italia-nel-2021-2013-anno-xvii (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Tarara, J.M.; Lee, J.; Spayd, S.E.; Scagel, C.F. Berry Temperature and Solar Radiation Alter Acylation, Proportion, and Concentration of Anthocyanin in Merlot Grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira de Orduña, R. Climate Change Associated Effects on Grape and Wine Quality and Production. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, E.; Ortiz, M.C.; Sarabia, L.A.; Íñiguez, M.; Puras, P. Modelling Phenolic and Technological Maturities of Grapes by Means of the Multivariate Relation between Organoleptic and Physicochemical Properties. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 761, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelsheim, D.; Busch, C.; Catena, L.; Champy, B.; Coetzee, J.; Coia, L.; Croser, B.; Draper, P.; Durbourdieu, D.; Frank, F.; et al. Climate Change: Field Reports from Leading Winemakers. J. Wine Econ. 2016, 11, 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Dubernet, M.; Duchêne, E.; Gowdy, M.; Marguerit, E.; Pieri, P.; Parker, A.; de Rességuier, L.; Ollat, N. An Update on the Impact of Climate Change in Viticulture and Potential Adaptations. Agronomy 2019, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.M.; Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. From Sugar of Grape to Alcohol of Wine: Sensorial Impact of Alcohol in Wine. Beverages 2015, 1, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannella, G.; Lombardi, S.J.; Coppola, F.; Vergalito, F.; Iorizzo, M.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; Iannini, C.; Sorrentino, E.; Coppola, R. Effect of Biofilm Formation by Lactobacillus plantarum on the Malolactic Fermentation in Model Wine. Foods 2020, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Wine Aroma Compounds in Grapes: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. An Overview of Climate Change Impacts on European Viticulture. Food Energy Secur. 2012, 1, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidi, B.S.; Rossouw, D.; Buica, A.S.; Bauer, F.F. Determining the Impact of Industrial Wine Yeast Strains on Organic Acid Production Under White and Red Wine-like Fermentation Conditions. S. Afr. j. enol. vitic. 2015, 36, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhao, N. Metabolomics of Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Omics and Functional Evaluation; Chen, W., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; pp. 167–182. ISBN 978-981-13-7832-4. [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi, V.; Tufariello, M.; De Simone, N.; Fragasso, M.; Grieco, F. Biodiversity of Oenological Lactic Acid Bacteria: Species- and Strain-Dependent Plus/Minus Effects on Wine Quality and Safety. Fermentation 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximum Acceptable Limits | OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/it/standards/international-code-of-oenological-practices/annexes/maximum-acceptable-limits (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Muccillo, L.; Gambuti, A.; Frusciante, L.; Iorizzo, M.; Moio, L.; Raieta, K.; Rinaldi, A.; Colantuoni, V.; Aversano, R. Biochemical Features of Native Red Wines and Genetic Diversity of the Corresponding Grape Varieties from Campania Region. Food Chem. 2014, 143, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Neira, A. Chapter 18 - Management of Astringency in Red Wines. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 257–272 ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5.

- Mori, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitayama, M.; Hashizume, K. Loss of Anthocyanins in Red-Wine Grape under High Temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-K.; Lan, Y.-B.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Duan, C.-Q. Targeted Metabolomics of Anthocyanin Derivatives during Prolonged Wine Aging: Evolution, Color Contribution and Aging Prediction. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delić, K.; Milinčić, D.D.; Pešić, M.B.; Lević, S.; Nedović, V.A.; Gancel, A.-L.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. Grape, Wine and Pomace Anthocyanins: Winemaking Biochemical Transformations, Application and Potential Benefits. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Zhu, J. A Quarter Century of Wine Pigment Discovery. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, F.; Picariello, L.; Forino, M.; Moio, L.; Gambuti, A. Comparison of Three Accelerated Oxidation Tests Applied to Red Wines with Different Chemical Composition. Molecules 2021, 26, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrufo-Curtido, A.; Ferreira, V.; Escudero, A. Factors That Affect the Accumulation of Strecker Aldehydes in Standardized Wines: The Importance of pH in Oxidation. Molecules 2022, 27, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleixandre-Tudo, J. l.; Lizama, V.; Álvarez, I.; Nieuwoudt, H.; García, M. j.; Aleixandre, J. l.; du Toit, W. j. Effect of Acetaldehyde Addition on the Phenolic Substances and Volatile Compounds of Red Tempranillo Wines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2016, 22, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Picariello, L.; Moio, L.; Waterhouse, A. Cabernet Sauvignon Aging Stability Altered by Micro-Oxygenation. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 70, ajev.2019–18061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years | Samples | pH | Titratable acidity (g/L) | Volatile acidity (g/L) |

Alcohol (%v/v) |

L-malic acid (g/L) |

L-lactic acid (g/L) |

Citric acid (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | 3.30 ± 0.01d | 7.28 ± 0.14a | 0.34 ± 0.04bc | 13.8 ± 0.1a | 0.21 ± 0.06c | 1.05 ± 0.05a | 0.25 ± 0.03c | |

| AC | 3.63 ± 0.02c | 5.55 ± 0.16b | 0.27 ± 0.02c | 13.2 ± 0.1b | 0.24 ± 0.06bc | 0.54 ± 0.03d | 0.37 ± 0.06a | |

| 2020 | AS | 3.80 ± 0.01a | 5.23 ± 0.13bc | 0.53 ± 0.05a | 12.4 ± 0.2c | 0.51 ± 0.07a | 1.05 ± 0.03a | 0.33 ± 0.01abc |

| CM | 3.70 ± 0.05bc | 4.85 ± 0.17c | 0.35 ± 0.05bc | 13.5 ± 0.2ab | 0.24 ± 0.06bc | 0.94 ± 0.04ab | 0.35 ± 0.01ab | |

| CC | 3.80 ± 0.05ab | 5.00 ± 0.20c | 0.40 ± 0.05abc | 14.0 ± 0.2a | 0.33 ± 0.05bc | 0.83 ± 0.05bc | 0.26 ± 0.01c | |

| CS | 3.70 ± 0.03bc | 5.15 ± 0.13bc | 0.41 ± 0.06ab | 11.5 ± 0.2d | 0.39 ± 0.01ab | 0.74 ± 0.03c | 0.27 ± 0.04bc | |

| AM | 3.28 ± 0.02c | 9.30 ± 0.20a | 0.24 ± 0.04d | 12.7 ± 0.1de | 2.46 ± 0.06a | 0.43 ± 0.07bc | 0.44 ± 0.01c | |

| AC | 3.32 ± 0.02c | 6.38 ± 0.12b | 0.39 ± 0.04c | 13.5 ± 0.3b | 1.32 ± 0.06c | 0.29 ± 0.08c | 0.53 ± 0.02b | |

| 2021 | AS | 3.78 ± 0.02a | 4.42 ± 0.17d | 0.49 ± 0.03b | 13.4 ± 0.1bc | 1.06 ± 0.04d | 0.63 ± 0.09ab | 0.37 ± 0.01cd |

| CM | 3.45 ± 0.05b | 5.40 ± 0.10c | 0.34 ± 0.04c | 14.5 ± 0.1a | 1.95 ± 0.05b | 0.29 ± 0.09c | 0.32 ± 0.02d | |

| CC | 3.54 ± 0.04b | 5.10 ± 0.10c | 0.59 ± 0.01a | 12.2 ± 0.2e | 0.84 ± 0.04e | 0.67 ± 0.03a | 0.61 ± 0.03a | |

| CS | 3.53 ± 0.05b | 4.54 ± 0.24d | 0.51 ± 0.02ab | 12.9 ± 0.1cd | 0.65 ± 0.02f | 0.46 ± 0.06abc | 0.41 ± 0.03c |

| Years | Anthocyanins | AM | AC | AS | CM | CC | CS |

| 2020 | Delf-3mg | 12.62 ±4.37 Aa | 3.30 ±0.22 Bb | 1.57 ±0.42 Ba | 8.87 ±2.52 Ab | 2.91 ±0.40 Bb | 4.50 ±0.81 Ba |

| Cyan-3mg | 0.43 ±0.09 ABb | 0.21 ±0.04 Cb | 0.21 ±0.17 Cb | 0.55 ±0.15 Aa | 0.35 ±0.03 ABCa | 0.24 ±0.06 BCb | |

| Pet-3mg | 16.96 ±4.59 Aa | 5.51 ±0.21 Cb | 3.22 ±0.45 Ca | 11.54 ±2.35 Bb | 6.91 ±0.87 Ca | 6.24 ±1.40 Ca | |

| Peon-3mg | 3.82 ±1.11 Bb | 8.50 ±0.88 Aa | 2.54 ±0.25 Ca | 0.91 ±0.28 Db | 0.82 ±0.09 Db | 2.56 ±0.32 Ca | |

| Malv-3mg | 145.10 ±26.50 Aa | 89.27 ±6.05 Bb | 101.74 ±9.34 Ba | 101.65 ±16.27 Ba | 88.06 ±9.26 Ba | 86.41 ±19.16 Ba | |

| Malv-Ac | 14.18 ±2.30 Ca | 5.78 ±0.32 Da | 9.57 ±1.18 CDa | 35.31 ±7.22 ABa | 41.56 ±4.27 Aa | 28.02 ±5.65 Ba | |

| Malv-Cum | 15.28 ±2.49 Aa | 8.86 ±0.77 BCDb | 9.64 ±1.25 BCa | 7.92 ±1.33 CDa | 11.19 ±1.40 Ba | 6.56 ±1.57 Da | |

| Delf-3mg | 13.01 ±4.09 Ba | 4.647 ±0.14 Ca | 1.28 ±0.33 Da | 17.21 ±1.41 Aa | 4.93 ±0.42 Ca | 3.89 ±0.09 CDa | |

| 2021 | Cyan-3mg | 0.86 ±0.27 Aa | 0.523 ±0.09 BCa | 0.46 ±0.04 BCa | 0.58 ±0.07 Ba | 0.38 ±0.18 BCa | 0.32 ±0.04 Ca |

| Pet-3mg | 14.73 ±1.08 Aa | 8.538 ±0.68 Ba | 2.94 ±0.12 Da | 14.43 ±1.19 Aa | 5.74 ±0.31 Cb | 3.85 ±0.11 Db | |

| Peon-3mg | 5.97 ±0.24 Aa | 5.174 ±0.17 Bb | 2.20 ±0.07 Cb | 5.60 ±0.51 ABa | 2.35 ±0.10 Ca | 2.35 ±0.07 Ca | |

| Malv-3mg | 125.64 ±8.13 Aa | 104.879 ±10.19Ba | 84.32 ±3.06 Cb | 104.94 ±8.36 Ba | 56.67 ±3.05 Db | 44.09 ±1.13 Eb | |

| Malv-Ac | 16.79 ±17.96 BCa | 4.485 ±0.68 Cb | 8.68 ±0.49 Ca | 35.99 ±2.64 Aa | 22.93 ±0.93 Bb | 15.01 ±0.37 BCb | |

| Malv-Cum | 11.36 ±2.59 Ab | 12.080 ±1.98 Aa | 4.21 ±0.34 Cb | 7.29 ±0.51 Ba | 3.40 ±0.28 Cb | 2.03 ±0.12 Cb |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).