Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Education Intervention

2.3. Anthropometry

2.4. Platform to Evaluate Athlete Knowledge of Sports Nutrition Questionnaire (PEAKS-NQ)

2.5. Athlete Food Choice Questionnaire (AFCQ)

2.6. Eating Behaviour and Diet Quality

2.7. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0)

2.8. Food Intake Diary

2.9. Low Energy Availability Questionnaire

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Participants

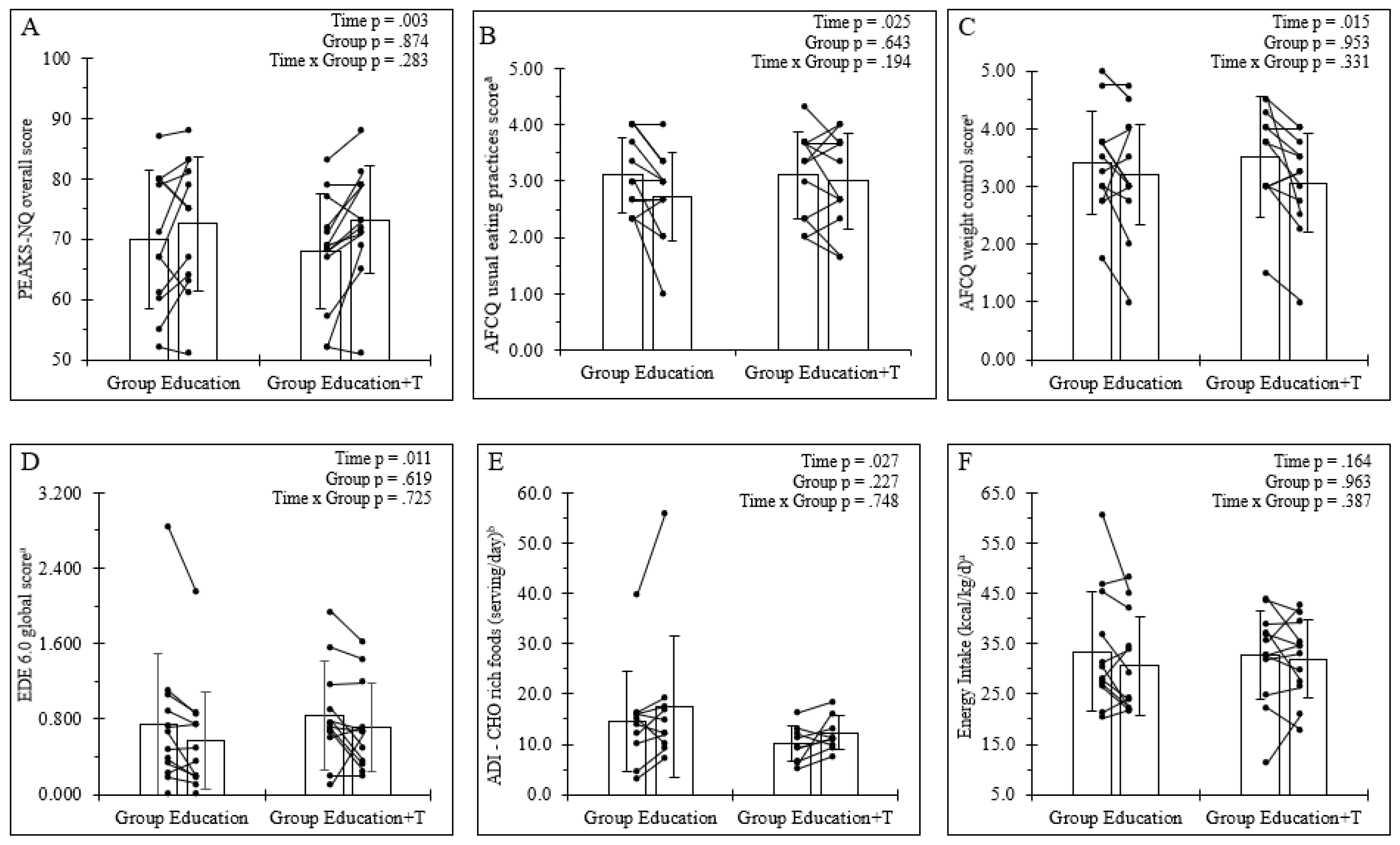

3.2. Changes in Factors Associated with Nutrition Knowledge

3.3. Changes in Factors Associated with Food Choices

3.4. Changes in Eating Behaviour and Dietary Intake

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADI AFCQ EDE 6.0 LEA LEAF-Q LEAM-Q PEAKS-NQ REDs |

Athlete diet index Athlete food choice questionnaire Eating disorder examination 6.0 Low energy availability Low energy availability female questionnaire Low energy availability male questionnaire Platform to evaluate athlete knowledge in sport nutrition questionnaire Relative energy deficiency in sports |

| EI:BMR | Energy intake:basal metabolic rate |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation - behaviour |

References

- Loucks, A. B., Kiens, B., & Wright, H. H. (2011). Energy availability in athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), Article sup1. [CrossRef]

- Wells, K. R., Jeacocke, N. A., Appaneal, R., Smith, H. D., Vlahovich, N., Burke, L. M., & Hughes, D. (2020). The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) position statement on disordered eating in high performance sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(21), 1247–1258. [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M., Ackerman, K. E., Bailey, D. M., Burke, L. M., Constantini, N., Hackney, A. C., Heikura, I. A., Melin, A., Pensgaard, A. M., Stellingwerff, T., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., Torstveit, M. K., Jacobsen, A. U., Verhagen, E., Budgett, R., Engebretsen, L., & Erdener, U. (2023). 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(17), 1073–1098. [CrossRef]

- Drew, M., Vlahovich, N., Hughes, D., Appaneal, R., Burke, L. M., Lundy, B., Rogers, M., Toomey, M., Watts, D., Lovell, G., Praet, S., Halson, S. L., Colbey, C., Manzanero, S., Welvaert, M., West, N. P., Pyne, D. B., & Waddington, G. (2018). Prevalence of illness, poor mental health and sleep quality and low energy availability prior to the 2016 Summer Olympic Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(1), 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Heikura, I. A., McCluskey, W. T. P., Tsai, M.-C., Johnson, L., Murray, H., Mountjoy, M., Ackerman, K. E., Fliss, M., & Stellingwerff, T. (2024). Application of the IOC Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) Clinical Assessment Tool version 2 (CAT2) across 200+ elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports-2024-108121. [CrossRef]

- McKay, A. K. A., Stellingwerff, T., Smith, E. S., Martin, D. T., Mujika, I., Goosey-Tolfrey, V. L., Sheppard, J., & Burke, L. M. (2022). Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 17(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. A., Appaneal, R. N., Hughes, D., Vlahovich, N., Waddington, G., Burke, L. M., & Drew, M. (2021). Prevalence of impaired physiological function consistent with Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): An Australian elite and pre-elite cohort. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Stok, F. M., Renner, B., Allan, J., Boeing, H., Ensenauer, R., Issanchou, S., Kiesswetter, E., Lien, N., Mazzocchi, M., Monsivais, P., Stelmach-Mardas, M., Volkert, D., & Hoffmann, S. (2018). Dietary Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Analysis and Taxonomy. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1689. [CrossRef]

- Thurecht, R. L., & Pelly, F. E. (2021). The Athlete Food Choice Questionnaire (AFCQ): Validity and Reliability in a Sample of International High-Performance Athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Alaunyte, I., Perry, J. L., & Aubrey, T. (2015). Nutritional knowledge and eating habits of professional rugby league players: Does knowledge translate into practice? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, O., Heikkilä, M., Linnamo, V., & Ihalainen, J. K. (2021). Nutrition Knowledge Is Associated with Energy Availability and Carbohydrate Intake in Young Female Cross-Country Skiers. Nutrients, 13(6), 1769. [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, O., Mikkonen, R., Mursu, J., Linnamo, V., & Ihalainen, J. K. (2023). Carbohydrate intake in young female cross-country skiers is lower than recommended and affects competition performance. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1196659. [CrossRef]

- Sesbreno, E., Blondin, D., Dziedzic, C., Sygo, J., Haman, F., Leclerc, S., Brazeau, A.-S., & Mountjoy, M. (2023). Signs of low energy availability in elite male volleyball athletes but no association with risk of bone stress injury and patellar tendinopathy. European Journal of Sport Science, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tam, R., Beck, K. L., Manore, M. M., Gifford, J., Flood, V. M., & O’Connor, H. (2019). Effectiveness of Education Interventions Designed to Improve Nutrition Knowledge in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine, 49(11), Article 11. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M. J., Mallinson, R. J., Strock, N. C. A., Koltun, K. J., Olmsted, M. P., Ricker, E. A., Scheid, J. L., Allaway, H. C., Mallinson, D. J., Kuruppumullage Don, P., & Williams, N. I. (2021). Randomised controlled trial of the effects of increased energy intake on menstrual recovery in exercising women with menstrual disturbances: The ‘REFUEL’ study. Human Reproduction, 36(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- Carter, J. L., Lee, D. J., Fenner, J. S. J., Ranchordas, M. K., & Cole, M. (2024). Contemporary educational and behavior change strategies improve dietary practices around a match in professional soccer players. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 21(1), 2391369. [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I. L., Melin, A. K., Garthe, I., Hollekim-Strand, S. M., Ivarsson, A., Koehler, K., Logue, D., Lundström, P., Madigan, S., Wasserfurth, P., & Torstveit, M. K. (2023). Effects of a 16-Week Digital Intervention on Sports Nutrition Knowledge and Behavior in Female Endurance Athletes with Risk of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Nutrients, 15(5), 1082. [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, Lehtovirta, Autio, Fogelholm, & Valve. (2019). The Impact of Nutrition Education Intervention with and Without a Mobile Phone Application on Nutrition Knowledge Among Young Endurance Athletes. Nutrients, 11(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Boidin, A., Tam, R., Mitchell, L., Cox, G. R., & O’Connor, H. (2021). The effectiveness of nutrition education programmes on improving dietary intake in athletes: A systematic review. British Journal of Nutrition, 125(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, M. R., Mitchell, N., Sutton, L., & Backhouse, S. H. (2019). Sports nutritionists’ perspectives on enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high performance sport: A qualitative analysis informed by the COM-B model and theoretical domains framework. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(18), Article 18. [CrossRef]

- Solly, H., Badenhorst, C. E., McCauley, M., Slater, G. J., Gifford, J. A., Erueti, B., & Beck, K. L. (2023). Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey. Nutrients, 15(11), 2519. [CrossRef]

- Tam, R., Beck, K., Scanlan, J. N., Hamilton, T., Prvan, T., Flood, V., O’Connor, H., & Gifford, J. (2021). The Platform to Evaluate Athlete Knowledge of Sports Nutrition Questionnaire: A reliable and valid electronic sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire for athletes. British Journal of Nutrition, 126(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Gillbanks, L., Mountjoy, M., & Filbay, S. R. (2022). Lightweight rowers’ perspectives of living with Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). PLOS ONE, 17(3), e0265268. [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A. J. (2006). How to randomize. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology, 4(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Davies, C., & Mann, A. (2023). Factors influencing women to accept diet and exercise messages on social media during COVID-19 lockdowns: A qualitative application of the health belief model. Health Marketing Quarterly, 40(4), 415–433. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. D., Marfell-Jones, M., Olds, T., & de Ridder, H. (2011). International standards for anthropometric assessment (pp. 1–112). International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry.

- Norton, K., & Olds, T. (1996). Measurement techniques in anthropometry. In Anthropometrica (pp. 25–75). University of the New South Wales Press, Australia.

- Withers, R. T., Whittingham, N. O., Norton, K. I., Forgia, J. L., Ellis, M. W., & Crockett, A. (1987). Relative body fat and anthropometric prediction of body density of female athletes. European Journal Applied Physiology, 56, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- de Lauzon, B., Romon, M., Deschamps, V., Lafay, L., Borys, J.-M., Karlsson, J., Ducimetière, P., Charles, M. A., & the Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Sante (FLVS) Study Group. (2004). The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 Is Able to Distinguish among Different Eating Patterns in a General Population. The Journal of Nutrition, 134(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Capling, L., Tam, R., Beck, K. L., Slater, G. J., Flood, V. M., O’Connor, H. T., & Gifford, J. A. (2021). Diet Quality of Elite Australian Athletes Evaluated Using the Athlete Diet Index. Nutrients, 13(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Canada’s Food Guide. Government of Canada. 2024 Nov 20. Available from: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2013). Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (n.d.). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370.

- Kuikman, M. A., Mountjoy, M., & Burr, J. F. (2021). Examining the Relationship between Exercise Dependence, Disordered Eating, and Low Energy Availability. Nutrients, 13(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- Moyen, A., Rappaport, A. I., Fleurent-Grégoire, C., Tessier, A.-J., Brazeau, A.-S., & Chevalier, S. (2022). Relative Validation of an Artificial Intelligence–Enhanced, Image-Assisted Mobile App for Dietary Assessment in Adults: Randomized Crossover Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(11), e40449. [CrossRef]

- Black, A. (2000). The sensitivity and specicity of the Goldberg cut-off for EI:BMR for identifying diet reports of poor validity. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J. J. (1991). Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: A synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Lundy, B., Torstveit, M. K., Stenqvist, T. B., Burke, L. M., Garthe, I., Slater, G. J., Ritz, C., & Melin, A. K. (2022). Screening for Low Energy Availability in Male Athletes: Attempted Validation of LEAM-Q. Nutrients, 14(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Melin, A., Tornberg, Å. B., Skouby, S., Faber, J., Ritz, C., Sjödin, A., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2014). The LEAF questionnaire: A screening tool for the identification of female athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I. L., Sjödin, A., Benardot, D., Tornberg, Å. B., Skouby, S., Faber, J., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., & Melin, A. K. (2018). Within-day energy deficiency and reproductive function in female endurance athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(3), 1139–1146. [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M. K., Fahrenholtz, I., Stenqvist, T. B., Sylta, Ø., & Melin, A. (2018). Within-Day Energy Deficiency and Metabolic Perturbation in Male Endurance Athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Sesbreno, E., Dziedzic, C. E., Sygo, J., Blondin, D. P., Haman, F., Leclerc, S., Brazeau, A.-S., & Mountjoy, M. (2021). Elite Male Volleyball Players Are at Risk of Insufficient Energy and Carbohydrate Intake. Nutrients, 13(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Capling, L., Gifford, J. A., Beck, K. L., Flood, V. M., Halar, F., Slater, G. J., & O’Connor, H. T. (2021). Relative validity and reliability of a novel diet quality assessment tool for athletes: The Athlete Diet Index. British Journal of Nutrition, 126(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Kerksick, C. M., Wilborn, C. D., Roberts, M. D., Smith-Ryan, A., Kleiner, S. M., Jäger, R., Collins, R., Cooke, M., Davis, J. N., Galvan, E., Greenwood, M., Lowery, L. M., Wildman, R., Antonio, J., & Kreider, R. B. (2018). ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: Research & recommendations. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 15(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Burke, L. M., Hawley, J. A., Wong, S. H. S., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2011). Carbohydrates for training and competition. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), Article sup1. [CrossRef]

- Sesbreno, E., Slater, G., Mountjoy, M., & Galloway, S. D. R. (2020). Development of an Anthropometric Prediction Model for Fat-Free Mass and Muscle Mass in Elite Athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 30(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Designing interventions to change eating behaviours. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 74(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., Gemming, L., Baker, D., & Braakhuis, A. (2017). Do Image-Assisted Mobile Applications Improve Dietary Habits, Knowledge, and Behaviours in Elite Athletes? A Pilot Study. Sports, 5(3), 60. [CrossRef]

- Strock, N. C. A., De Souza, M. J., Mallinson, R. J., Olmsted, M., Allaway, H. C. M., O’Donnell, E., Plessow, F., & Williams, N. I. (2023). 12-months of increased dietary intake does not exacerbate disordered eating-related attitudes, stress, or depressive symptoms in women with exercise-associated menstrual disturbances: The REFUEL randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 152, 106079. [CrossRef]

| Intervention Function | Definition | Link to components of COM-B model | Educational content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group education | Group education + testimonials | |||

| Education | Increase knowledge or understanding | Capacity-psychological Motivation-reflective |

|

|

| Persuasion | Using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action | Motivation-reflective Motivation-automatic |

||

| Persuasion | Using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action | Motivation-reflective Motivation-automatic |

|

|

|

Group education (n = 12; 3 female) |

Group education + testimonials (n = 13; 3 female) |

p value | |

| Age (years) | 25.4 ± 2.8 | 24.1 ± 2.9 | 0.288 |

| Anthropometry | |||

| Body mass (kg) | 75.9 ± 17.0 | 68.4 ± 10.0 | 0.187 |

| Standing height (cm) | 172.4.7 ± 10.6 | 168.0 ± 6.6 | 0.221 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 3.8 | 24.2 ± 2.3 | 0.383 |

| Sum of skinfolds (mm) | 66.1 ± 41.3 | 49.4 ± 14.7 | 0.584 |

| Ectomorphya | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.847 |

| Mesomorphya | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 0.300 |

| Endomorphya | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 0.847 |

| Positive for low energy availability risk (n) | |||

| LEAM-Q score | 3 | 0 | |

| LEAF-Q score | 3 | 2 | |

| Primary sport (n) | |||

| Sprint kayak | 2 (0 female) | 2 (2 female) | |

| Amateur boxing | 2 (1 female) | 2 (0 female) | |

| Olympic weightlifting | 3 (1 female) | 1 (0 female) | |

| Artistic gymnastics | 4 (0 female) | 6 (0 female) | |

| Trampoline gymnastics | 1 (1 female) | 2 (1 female) | |

| Stage of training cycle (n) | |||

| In-season | 9 (3 female) | 9 (1 female) | |

| Injured/off-season | 3 (0 female) | 4 (2 female) | |

| Training history (n) | |||

| Training 11-15 hours/week | 1 (0 female) | 1 (0 female) | |

| Training 16-20 hours/week | 5 (2 female) | 5 (1 female) | |

| Training 20+ hours/week | 8 (1 female) | 7 (2 female) | |

|

Group education (n = 12; 3 female) |

Group education + testimonial (n = 13; 3 female) |

p value | |

| Factors associated with food choice | |||

| Weekly food budget ($) | 100 (50-350) | 150 (80-500) | 0.114 |

| AFCQ Nutritional attributes of food | 3.53 ± 0.82 | 3.23 ± 0.82 | 0.406 |

| AFCQ Usual eating practices | 3.11 ± 0.67 | 3.10 ± 0.74 | 0.979 |

| AFCQ Food and health awareness | 3.75 ± 0.57 | 3.50 ± 0.64 | 0.315 |

| AFCQ Influence of others | 2.25 ± 0.98 | 2.21 ± 0.66 | 0.896 |

| AFCQ Weight control | 3.42 ± 0.89 | 3.54 ± 0.83 | 0.726 |

| AFCQ Food values and beliefs | 1.86 ± 0.50 | 1.59 ± 0.70 | 0.225 |

| AFCQ Performance | 4.25 ± 0.59 | 4.03 ± 0.80 | 0.470 |

| AFCQ Emotional influences | 2.17 ± 0.53 | 2.37 ± 0.66 | 0.437 |

| AFCQ Sensory appeal | 4.14 ± 0.52 | 3.95 ± 0.79 | 0.769 |

| Culinary skillsa (n) | |||

| Advanced | 4 (2 female) | 7 (2 female) | |

| Intermediate | 7 (1 female) | 5 (1 female) | |

| Basic | 1 (0 female) | 1 (0 female) | |

| Cooking (n) | |||

| Always | 6 (2 female) | 6 (2 female) | |

| Usually | 1 (1 female) | 3 (1 female) | |

| Sometimes | 1 (0 female) | 2 (0 female) | |

| Rarely | 4 (0 female) | 1 (0 female) | |

| Never | 0 (0 female) | 1 (0 female) | |

| Eating behaviour | |||

| Dietary supplement use (n)b | 5 (3 female) | 5 (3 female) | |

| Dietary intake/nutrition | |||

| Energy (g/kg/d) | 33.4 ± 11.9 | 32.7 ± 8.9 | 0.868 |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg/d) | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 0.728 |

| Protein (g/kg/d) | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 0.611 |

| Fat (% of energy) | 33.6 ± 6.4 | 34.3 ± 5.6 | 0.775 |

| ADI total score | 77.1 ± 15.2 | 72.3 ± 11.3 | 0.410 |

| ADI Core Nutrition sub-score | 50.7 ± 11.2 | 50.9 ± 8.4 | 0.959 |

| ADI Special Nutrients sub-score | 19.5 ± 4.6 | 15.1 ± 4.5 | 0.036 |

| ADI Dietary Habits sub-score | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 0.228 |

|

Group education (n = 12, 3 female) |

Group education + testimonials (n = 13, 3 female) |

P values | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Grp | Time | Grp x Time | |

| Psychological capability | |||||||

| PEAKS-NQ general | 69.3 ± 11.9 | 72.8 ± 7.4 | 75.7 ± 8.9 | 79.3 ± 6.7 | 0.050 | 0.052 | 0.954 |

| PEAKS-NQ sport | 70.1 ± 11.2 | 71.9 ± 16.5 | 61.5 ± 13.1 | 67.9 ± 13.4 | 0.225 | 0.058 | 0.277 |

| AFCQ nutritional attributes of fooda | 3.53 ± 0.82 | 3.38 ± 1.02 | 3.28 ± 0.83 | 3.22 ± 0.82 | 0.544 | 0.367 | 0.727 |

| AFCQ usual eating practicesa | 3.11 ± 0.67 | 2.72 ± 0.78 | 3.11 ± 0.77 | 3.00 ± 0.84 | 0.643 | 0.025 | 0.194 |

| AFCQ food and health awarenessa | 3.75 ± 0.57 | 2.65 ± 0.54 | 3.45 ± 0.65 | 3.48 ± 0.52 | 0.248 | 0.752 | 0.637 |

| Social opportunity | |||||||

| AFCQ influence of othersa | 2.24 ± 0.98 | 2.19 ± 0.91 | 2.22 ± 0.69 | 2.11 ± 0.66 | 0.863 | 0.444 | 0.794 |

| Reflective motivation | |||||||

| AFCQ weight controla | 3.42 ± 0.88 | 3.21 ± 1.05 | 3.52 ± 0.86 | 3.06 ± 0.85 | 0.953 | 0.015 | 0.331 |

| AFCQ food values and beliefsa | 1.86 ± 0.50 | 1.92 ± 0.45 | 1.64 ± 0.70 | 1.81 ± 0.78 | 0.470 | 0.330 | 0.636 |

| AFCQ performancea | 4.25 ± 0.59 | 4.08 ± 0.67 | 4.06 ± 0.87 | 4.02 ± 0.55 | 0.645 | 0.790 | 0.604 |

| Automatic motivation | |||||||

| AFCQ emotional influencesa | 2.17 ± 0.52 | 2.29 ± 0.86 | 2.31 ± 0.66 | 2.10 ± 0.57 | 0.934 | 0.698 | 0.130 |

| AFCQ sensory appeala | 4.14 ± 0.52 | 3.80 ± 0.66 | 4.03 ± 0.77 | 3.89 ± 0.74 | 0.949 | 0.036 | 0.377 |

| Eating behaviour | |||||||

| EDE 6.0 Intake subscorea | 0.708 ± 0.663 | 0.558 ± 0.596 | 0.567 ± 0.360 | 0.483 ± 0.430 | 0.311 | 0.218 | 0.721 |

| EDE 6.0 Physique concern subscorea | 0.766 ± 0.847 | 0.588 ± 0.655 | 1.106 ± 0.821 | 0.937 ± 0.735 | 0.274 | 0.009 | 0.946 |

| TFEQ-R18 restraint eating scorea | 13.5 ± 3.8 | 13.6 ± 4.5 | 14.1 ± 3.5 | 13.0 ± 3.3 | 0.976 | 0.442 | 0.442 |

| ADI - fruit (serves/day) b | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 0.530 | 0.392 | 0.630 |

| ADI - non-Starchy Vegetables (serves/day)b | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 0.945 | 0.743 | 0.386 |

| ADI - starchy Vegetables (serves/day)b | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 0.810 | 0.026 | 0.737 |

| ADI - grains (serves/day) b | 5.9 ± 3.0 | 4.2 ± 2.0 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 1.3 | 0.865 | 0.045 | 0.339 |

| ADI - dairy (serves/day) b | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.468 | 0.008 | 0.584 |

| ADI - meat (serves/day) b | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 0.328 | 0.522 | 0.882 |

| ADI - discretionary food (serves/day) b | 4.1 ± 8.8 | 6.6 ± 12.8 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 0.274 | 0.025 | 0.271 |

| ADI - alcohol (serves/week) b | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 2.4 | 1.8 ± 2.9 | 0.730 | 0.161 | 0.538 |

| Dietary intake | |||||||

| Carbohydrate (g/kg/d)a | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 0.822 | 0.746 | 0.502 |

| Protein (g/kg/d)a | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.954 | 0.113 | 0.672 |

| Fat (% of energy)a | 33.6 ± 6.4 | 33.2 ± 7.1 | 34.6 ± 5.7 | 34.8 ± 6.2 | 0.592 | 0.901 | 0.815 |

| ADI total scoreb | 77.1 ± 15.2 | 71.6 ± 13.8 | 72.3 ± 11.3 | 70.4 ± 10.4 | 0.525 | 0.206 | 0.535 |

| ADI Core Nutrition sub-scoreb | 50.7 ± 11.2 | 48.3 ± 8.4 | 50.9 ± 8.4 | 49.1 ± 7.0 | 0.879 | 0.270 | 0.881 |

| ADI Special Nutrients sub-scoreb | 19.5 ± 4.6 | 16.2 ± 6.5 | 15.1 ± 4.5 | 14.5 ± 4.6 | 0.118 | 0.096 | 0.236 |

| ADI Dietary Habits sub-scoreb | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 0.288 | 0.088 | 0.451 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).