1. Introduction

Ultrasonic wave propagation is a powerful technique used in a wide range of fields, from non-destructive testing (NDT) and material characterization to medical diagnostics. The study of how ultrasonic waves behave as they travel through materials provides essential information about the internal structure and mechanical properties of the materials being tested. In traditional models, wave propagation is typically described using classical elasticity theory, where the stress-strain relationship of the material depends on the first derivatives of the displacement field, representing the strain. Although this approach works well for simple, homogeneous materials, it is insufficient for more complex materials that possess microstructural heterogeneity or exhibit non-local interaction, since these materials often exhibit non-local behavior, meaning that the response at any given point in the material is influenced not only by the immediate surroundings but also by broader microstructural features. Second-gradient elasticity theory was developed to address this issue by introducing higher-order derivatives of the displacement field, which enables the model to capture these non-local effects and internal length scales within the material. Then, this theory has become particularly useful for modeling materials that exhibit scale-dependent behavior, such as foams, granular materials, and biological tissues. By incorporating second-gradient terms into the stress-strain relationship, this theory provides a more accurate description of wave propagation in materials with microstructural features, where the classical theory would not capture the complex interactions between the structure of the material and the propagating wave [

1,

2].

Dispersion refers to the phenomenon in which the speed of a wave depends on its frequency. In most classical wave propagation theories, the velocity of the wave is constant and independent of frequency. However, in second-gradient media, the wave velocity is frequency-dependent. This is because the material’s internal structure, captured e.g. by the second-gradient terms, affects the wave’s propagation at different frequencies. This effect can be especially pronounced in materials where microstructural characteristics, such as pores, inclusions, or heterogeneity, influence wave propagation [

3,

4]. In practice, the dispersion observed in second-gradient media can lead to significant differences in how waves propagate, especially at higher frequencies. This has important implications for the design and analysis of materials such as metamaterials, where customizable dispersion characteristics are often desired to achieve specific effects, such as negative refraction or slow-wave propagation [

5]. Similarly, in biological tissues, where wave dispersion is influenced by the cellular structure of the tissue, understanding dispersion becomes critical to improving medical imaging techniques such as ultrasound elastography [

6].

Attenuation refers to the loss of energy that occurs when a wave propagates through a medium. In traditional wave theory, attenuation is typically associated with damping mechanisms, such as viscoelastic effects or material imperfections. However, in materials exhibiting second-gradient behavior, attenuation can arise due to the non-local interactions and microstructural features that influence wave propagation. As ultrasonic waves pass through a material with second-gradient effects, their energy is dissipated in a way that cannot be fully explained by classical damping models [

7,

8]. The attenuation in such materials is also frequency-dependent, with the energy loss being more significant at higher frequencies. This frequency-dependent attenuation is crucial for understanding wave behavior in biological tissues, where the microstructural properties of the tissue (such as cellular arrangements) can cause additional dissipation of wave energy. Similarly, in porous materials and composites, where waves interact with heterogeneities at multiple scales, the attenuation behavior provides valuable insight into the material’s internal structure and mechanical properties [

9].

The theoretical framework of second-gradient elasticity, which includes both dispersion and attenuation effects, has several important applications. Understanding the frequency-dependent dispersion and attenuation can enhance the sensitivity and resolution of ultrasonic testing techniques, allowing for better detection of defects, cracks, or voids within materials [

9]. In medical diagnostics, particularly in ultrasound elastography, these models can provide a more accurate representation of wave propagation through biological tissues. Since tissues often exhibit complex internal structures, the ability to account for non-local effects and microstructural interactions improves the precision of measurements, leading to more reliable assessments of tissue stiffness or elasticity. This has important implications for early diagnosis and monitoring of conditions such as tumors or liver fibrosis [

6]. Additionally, the study of second-gradient effects in ultrasonic wave propagation is crucial for the development of metamaterials, engineered materials designed to have specific wave propagation characteristics. By tailoring the second-gradient parameters, researchers can design materials with bespoke dispersion and attenuation properties, opening up new possibilities for applications in sensing, communication, and imaging technologies [

5]. Last but not least, we would like to highlight a recent contribution that has significantly inspired our work, specifically the thesis by Ronny Hofmann[

10]. His study focuses on laboratory measurements of clastic rocks, ranging from 3 Hz to 500 kHz, and their application to well log analysis and a time-lapse study in the North Sea. Within this framework, the measurements reveal substantial dispersion in sandstones due to the saturation of inhomogeneities and open boundaries (such as pore pressure diffusion), which in turn affects the material’s compressibility and stiffness.

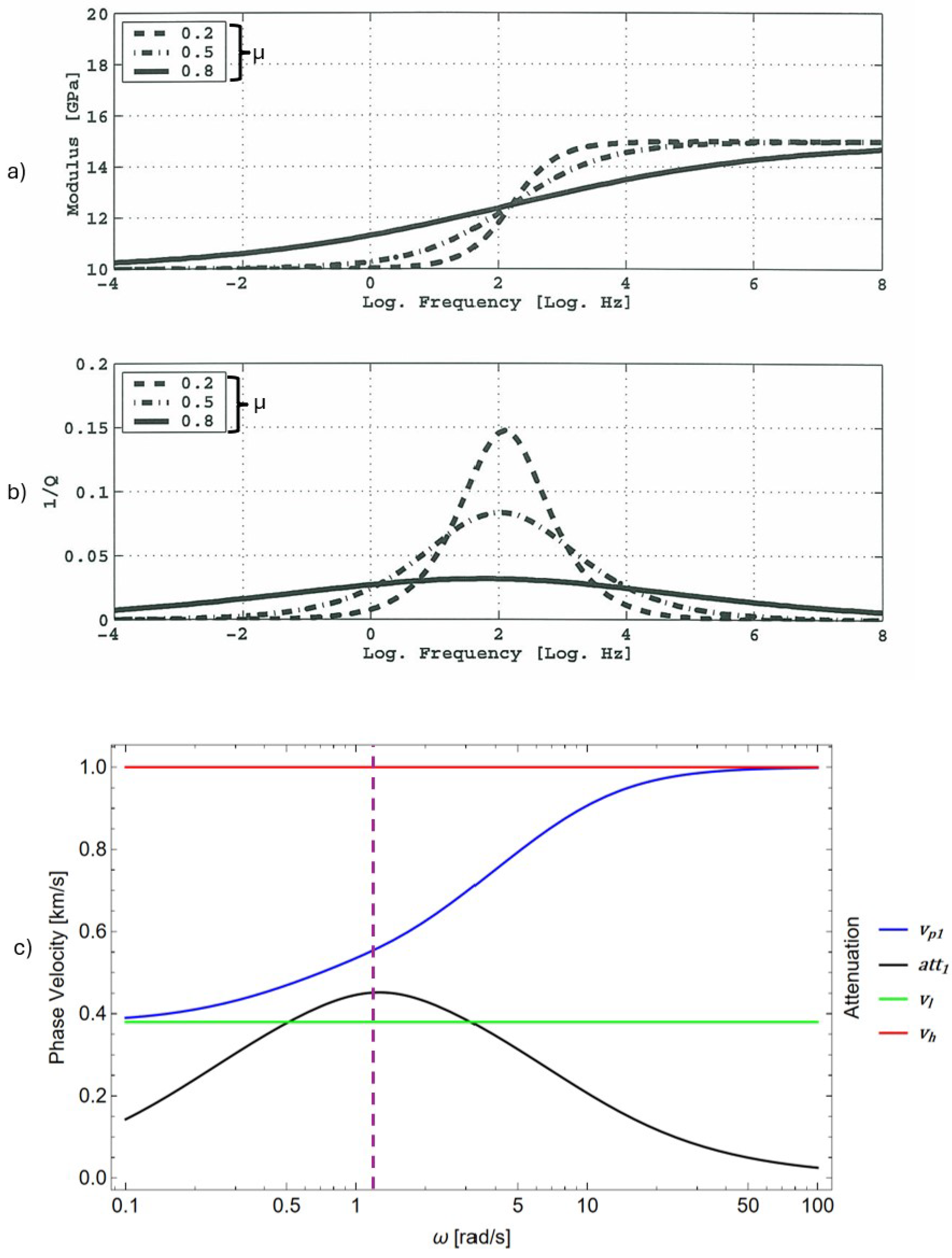

Furthermore, attenuation is directly related to the rate of change of the modulus. This concept is summarized in

Figure 1 [

10], which illustrates that a certain parameter

defined in Hofmann’s thesis [

10] changes i.e. from 0.8 to 0.2, the dispersion of phase velocities is higher as

Figure 1a and the attenuation peaks in

Figure 1b become more pronounced. The variation of phase velocity occurs at peak attenuation frequency, as for

Figure 1c.

Since no continuous model currently exists that can capture the aforementioned effect, the aim of this research is to provide a model that, starting from the Rayleigh-Hamilton principle and considering both the material’s internal viscosity and second-gradient parameters, can simulate the aforementioned dispersive and dissipative effects.

Beside the Introduction, the paper is organized into the following sections:

Section 2 outlines the construction of the governing equations based on the Hamilton-Rayleigh principle, considering both internal viscosity and second gradient parameters of the material. Starting from the dispersion equation and using the wave form solution we derive the wavenumber, then the velocity phase and the quality factor for the evaluation of attenuation phenomena. Once the methodology and model have been finalized, we search for materials and experimental data from the literature to validate the model.

Section 3 focuses on the validation of the above model. Three case studies from the literature (one involving natural materials and two involving artificial materials) are examined. The purpose is to compare experimental data with the numerical simulation results derived from the model. Results and comments on the comparison above mentioned are also discussed in this section. Moreover, we have introduced a numerical simulation to evaluate general aspects of the wave’s behavior, both from the perspective of dispersion and attenuation.

Finally,

Section 4 offers our conclusions, reflections on future developments and reports all the contributions.

A list of abbreviations used in the manuscript and all the references adopted for this study are presented at the end of the article.

2. Modelling and Methods

2.1. Scope and Strategy

We are searching for a model that can reproduce the variation of phase velocity and attenuation with wave frequency for a given material, as shown in

Figure 1c, that is our benchmark. In this context, we will consider the Rayleigh-Hamilton principle, using second-gradient and viscous parameters to describe the displacement involved in the energies represented in the principle. The Partial Differential Equation (PDE) obtained will be solved using a wave form solution to derive the dispersion equation that includes phase velocity and attenuation.

2.2. Variational Derivation of Governing Equations (PDE and BCs)

We begin by recalling the extended Rayleigh-Hamilton principle that postulates the variation of the Action,

, to be connected to the Rayleigh function

R:

where the three energy functions

K, the kinetic energy density,

W, the potential energy density, and

, the external energy function, are equal to:

and the Raylegh function is:

We recall that and are the standard elastic modulus for a linear one-dimensional elastic body and the non-standard strain-gradient modulus, respectively; given the displacement u, its derivatives with respect to time are denoted by and with respect to space (first derivative) or (second derivative), and are the mass density (mass per unit length) and the micro-inertia of the mono-dimensional body, respectively; and are the external distributed (per unit length) forces and double forces, respectively; (or ) and (or ) are the concentrated forces and double forces, evaluated at the extrema at (or at ) of the one-dimensional body, respectively. Meanwhile, in the Raylegh function two internal viscosity are present, related to first gradient field and related to second gradient field.

Replacing (2), (3), (4) and (5) in the left side of Equation (

1) and integrating by parts, for every admissible variation of the displacement filed, the variation of the Action,

, can be reduced to:

The variation of Raylegh function will be:

that integrating by parts, in space and time, becomes:

Then, replacing equations (8) and (6) in (1) and ordering we obtain:

where, since the displacement

is assumed to be prescribed both at

and at

, we have that

. Equation (

9) must hold for every admissible variation

of the displacement field

u. So, the last four addends of Equation (

9) must therefore be null. On one hand, if the displacement

u or the displacement gradient

are prescribed at the boundary (i.e., the left-hand sides of the following equations are satisfied), then its variation is null as well as the corresponding line of Equation (

9). On the other hand, to make null the same lines of Equation (

9), if the mentioned kinematic conditions are not prescribed, then the right-hand sides of the following equations are satisfied:

for every instants of time, e.g.,

. Finally, also the first line of Equation (

9) must be zero for every admissible variation

of the displacement field. Thus, because of its arbitrariness, it results:

2.3. Wave form solution

Equation (

14) is the Partial Differential Equation (PDE) governing the evolution of the displacement field

for the investigated model, that will be solved in the following two subsections. In particular, we search for (14) a wave form solution and we assume the body length

L to be sufficiently large so that the boundary conditions (BCs) (10)-(13) do not influence the solution.

Equation (

14) can be solved considering no external distributed actions (

and

) in the form of the following plane wave solution for the displacement field:

where

is the complex wave amplitude,

is the frequency of the wave expressed in Rad/s,

is the complex wave number,

i is the imaginary unit and Re is the real part operator. Calculating the derivatives of (15) and replacing them into (14), it results:

where the arbitrariness of the complex wave amplitude

has been considered. Equation (

16) is a fourth-degree algebraic equation in terms of

, and therefore admits four complex solutions for

. However, in (16)

appears only with even powers (

or

). Thus, if

=

is a solution of (16) also

= -

is a solution as a consequence, then two of these solutions correspond to right-hand propagating waves, while the other two are equal in magnitude and opposite in sign. The reason is the isotropy of the domain. In the formulae, two independent solutions are:

Remembering the correlation between frequency

, wave number

and phase velocity

[

11], we obtain an expression for the two phase velocities:

Similarly, starting from the wave number

, it is possible to determine the corresponding two quality factors

and

[

10] as the inverse of the damping ratio

, then as a function of the real/imaginary parts of the wave number:

In conclusion, equations (18) and (19) serve as the reference for our model, linking phase velocity and attenuation to the frequency of the wave propagating through the material.

3. Validation: Results and Discussion

3.1. Introduction

As already highlighted in the introduction of this manuscript, we want to validate this model with data available for common construction material in the literature [

12,

13]. Such literature has been selected because, within many available articles, both phase velocity and attenuation measurements have been made for the same material at same frequencies. In detail, we investigate a sandstone sample [

12], a cement paste sample [

13]and finally a concrete sample [

13]. For each material we have developed a case of study, then the validation is obtained by superimposing the theoretical predictions (obtained from numerical simulations) with the experimental data. In detail, first, we propose a numerical simulation that allows us to make general considerations about the dispersive behavior of the wave, characteristic of our model. Second, we validate the model using the materials presented above, comparing the available experimental data with the numerical simulation. The material constitutive parameters used in this section are presented in

Table 1.

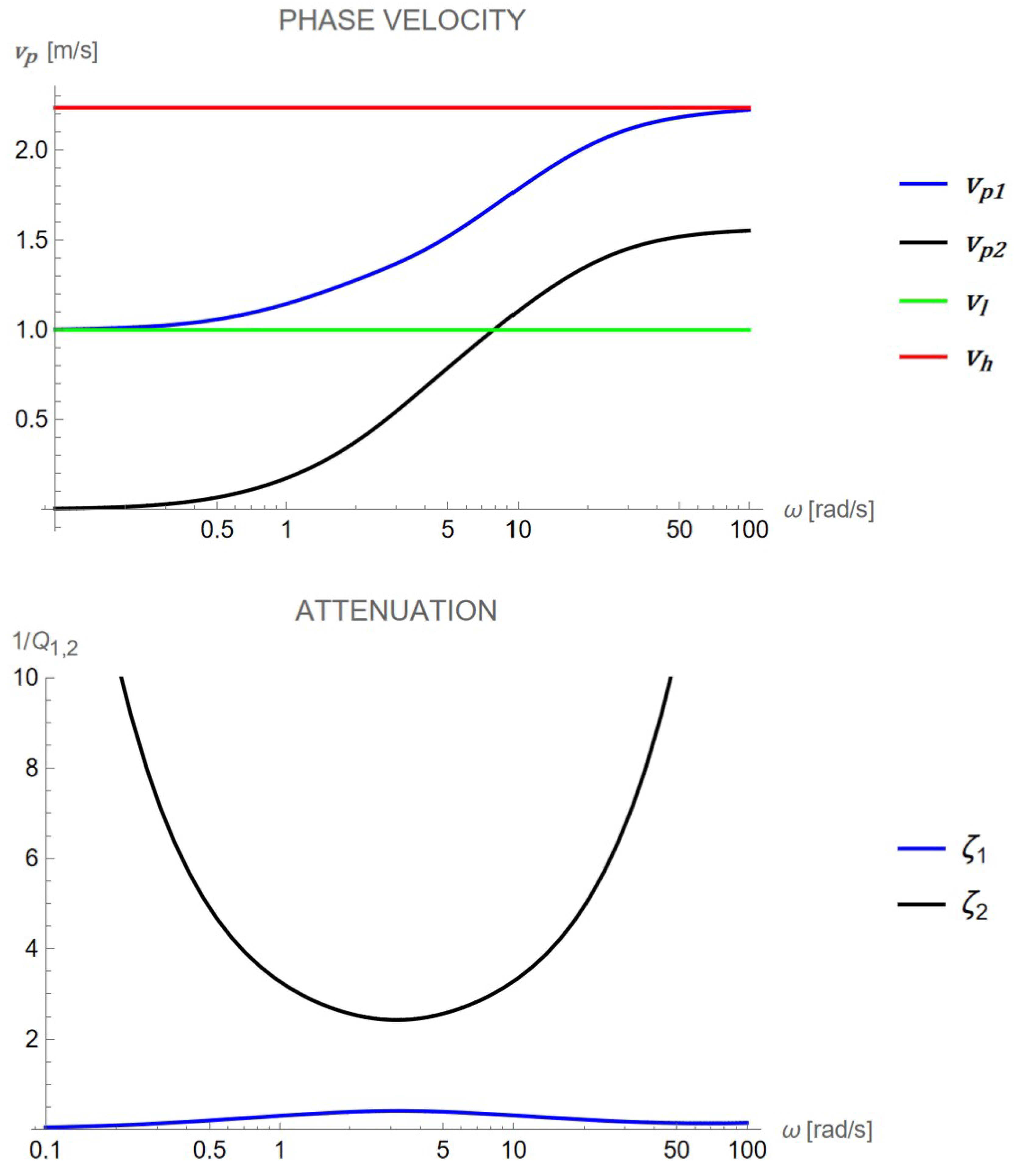

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 refer to the numerical simulation toward the benchmark (

Figure 1), while

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 refer to the case studies.

3.2. Numerical Simulation Toward to the Benchmark

In

Figure 2, we show for the numbers explained in Table 1 a graphical representation of the two phase velocities (18) and their respective attenuations (19) for the same values of the material characteristics present in Table 1. For

and

equal to zero,

is zero, while

asymptotically tends to the velocities for low-frequency regime

and for the high-frequency regime

as follows:

For

and

different from zero, we observe in

Figure 2 that the wave with phase velocity

has a much higher attenuation than the wave with phase velocity

, thus making it experimentally unmeasurable. Moreover, the variation of velocity from low to high frequency regimes occurs at a characteristic frequency for both waves, corresponding to the attenuation peak. For certain values of the viscosities

and

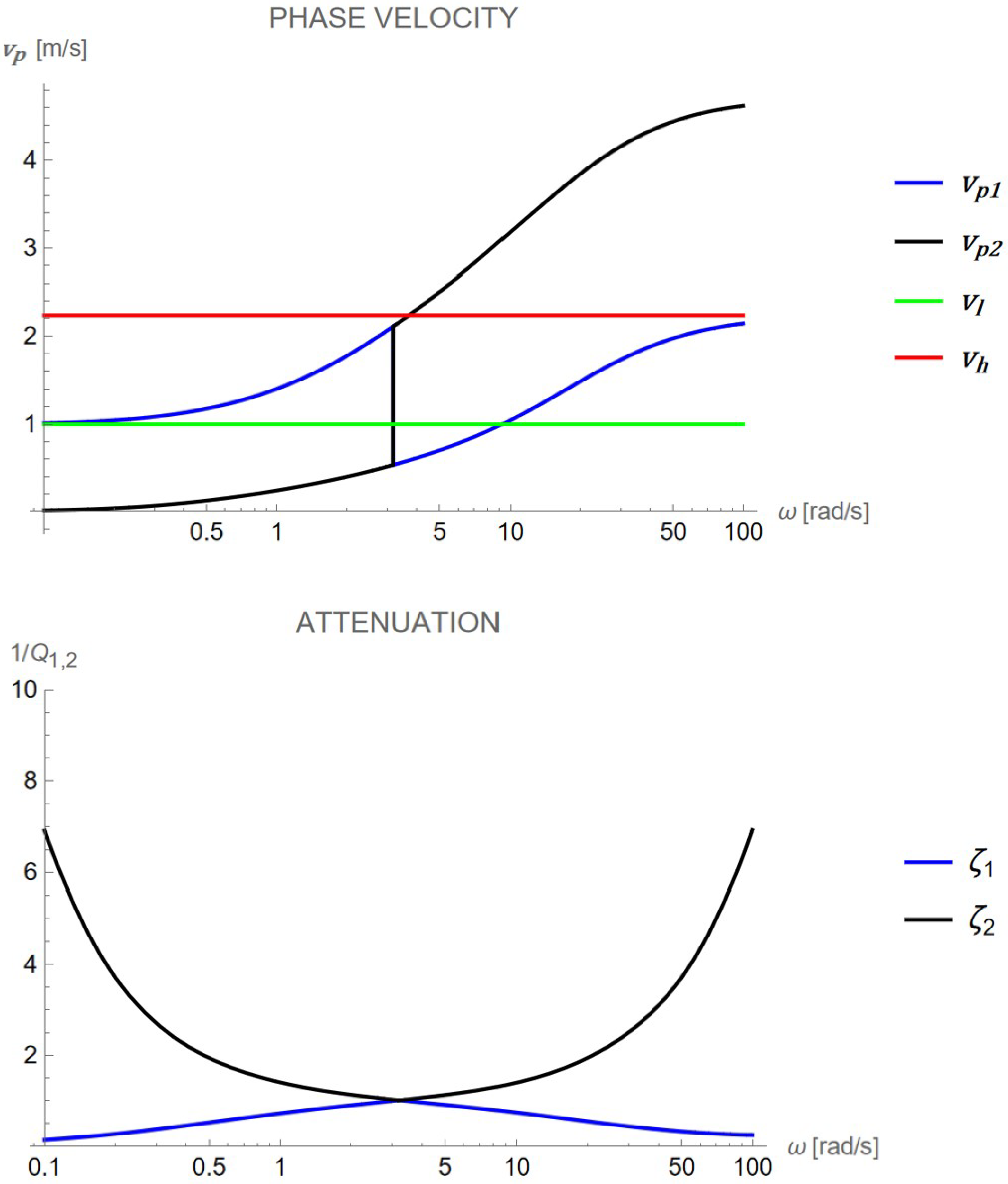

, we can observe, as shown in

Figure 3, a jump in the values of the phase velocities

and

, at the frequency at which the attenuation curves of the two signals exhibit a common peak. Nevertheless, the phase velocity measurable by ultrasonic instruments will be in all the cases the one with the lower attenuation, that is,

in the numerical example considered.

3.3. Validation with Data from Literature

Since experimental attenuation measurements available in the literature are generally expressed as the loss of signal amplitude between one end and the other of the sample along its length

L and are measured in (dB/m), it is useful to introduce an attenuation coefficient, according the following formulation[

12]:

Replacing (15) into (22), using the Eulero proprieties and considering the real part and the imaginary part of the wavenumber, we obtain:

where in the wavenumber we can omit the real part since, due to the fact we use maxim values of amplitude in (23), the cosine of the wavenumber, corresponding to the its real part, assume values for sure lower than those referred to the imaginary part. Once the material stiffness parameters, microstructure, micro-inertias, and density are set, the next step is to evaluate how variations in the internal viscosity of the material influence the combination of parameters that best approximate the experimental data for phase velocity and attenuation.

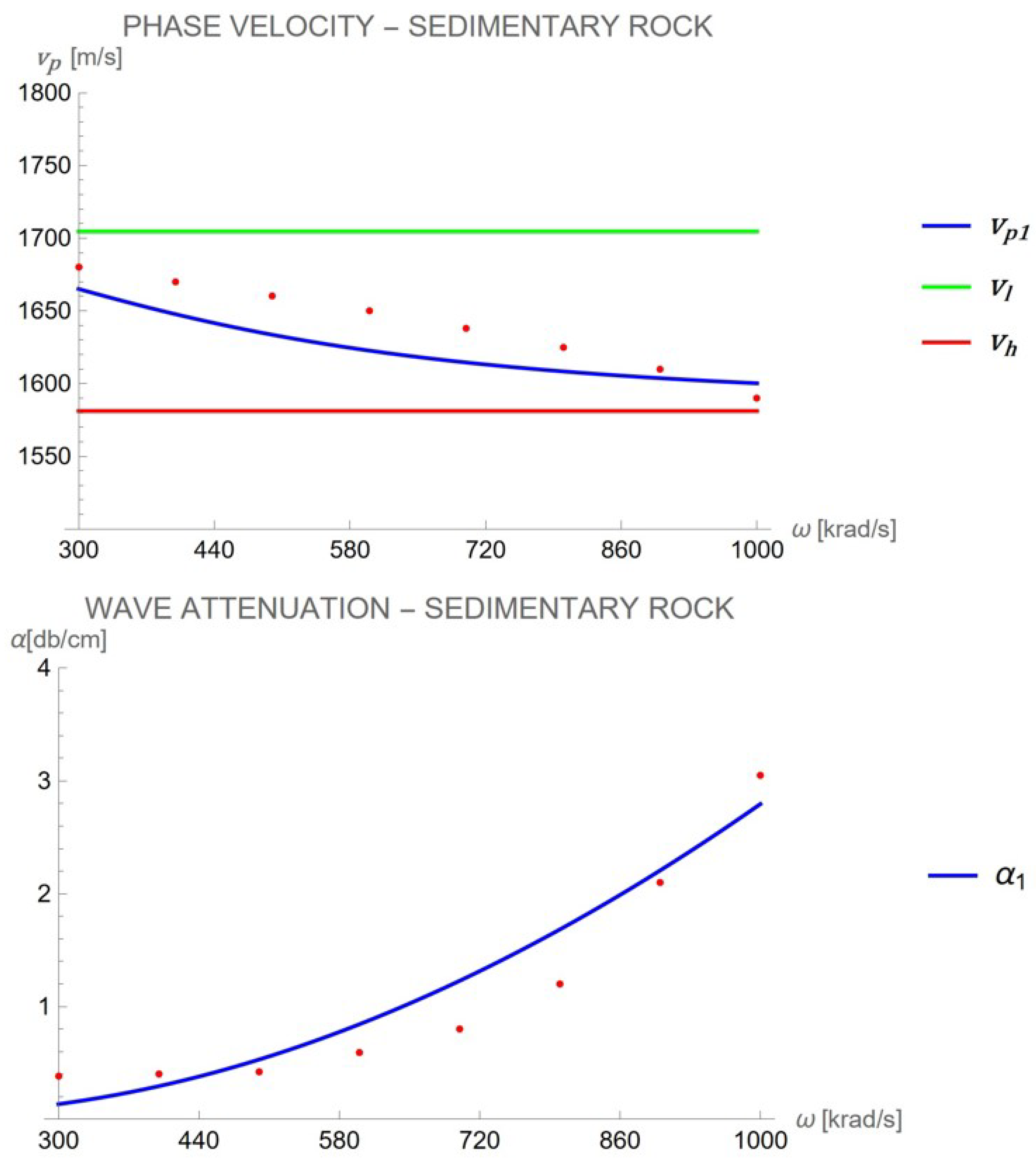

3.3.1. 1st Case of Study: Sandstone

The sediment specimen was prepared in a 100 mm × 100 mm × 50 mm container immersed in water to optimize velocity dispersion and minimize ultrasonic pulse attenuation [

12]. The experiment took place in a 650 mm × 750 mm × 1500 mm water bath, using two matched pairs of broadband transducers with center frequencies of 0.5 MHz and 1.0 MHz[

12]. The transducers were aligned coaxially with a 150 mm separation, mounted on a stable frame to ensure accurate wave amplitude measurements and prevent pressure variations on the probes [

12] . In this case of study we know already the bulk modulus of the material and its density, so the phase velocity for low regime frequency is immediately obtained by Equation (20). The values of microstructure and micro-inertia can be derived by calculating the characteristic length of the material, taking in account the fact that the velocity in the high-frequency regime is lower than that in the low-frequency regime according experimental data. In

Figure 4, we present the overlap between numerical simulation, using the constitutive parameters of Table 1, and experimental data for phase velocity and wave attenuation in the tested material. In the frequency range of investigation, no attenuation peak is observed. The monotone trend observed in both phase velocity (decreasing) and attenuation (increasing) is successfully captured by the numerical simulation, confirming the model’s accuracy in describing wave propagation behavior.

3.3.2. 2nd Case of Study: Cement Paste

The specimens tested were cubic of 150 mm edge, the experimental setup is a simple through-transmission ultrasonic configuration, using a waveform generator board and two broadband transducers of frequency between 300 kHz and 1 MHz, and a data acquisition system [

13]. We consider the data for a sample with ratio water/ciment=0.375[

13]. In

Figure 5 we can compare experimental data with model numerical simulation. The velocity phase suddenly decreases (at 200 kHz) till to tend to the velocity for high frequency regime; in the attenuation graphic we observe the increasing trend, although a resonance peak can be observed at 100 kHz in the experimental data, probably due to other effects not included in the model as internal micro-fractures with inclusion of fluids or a measurement error.

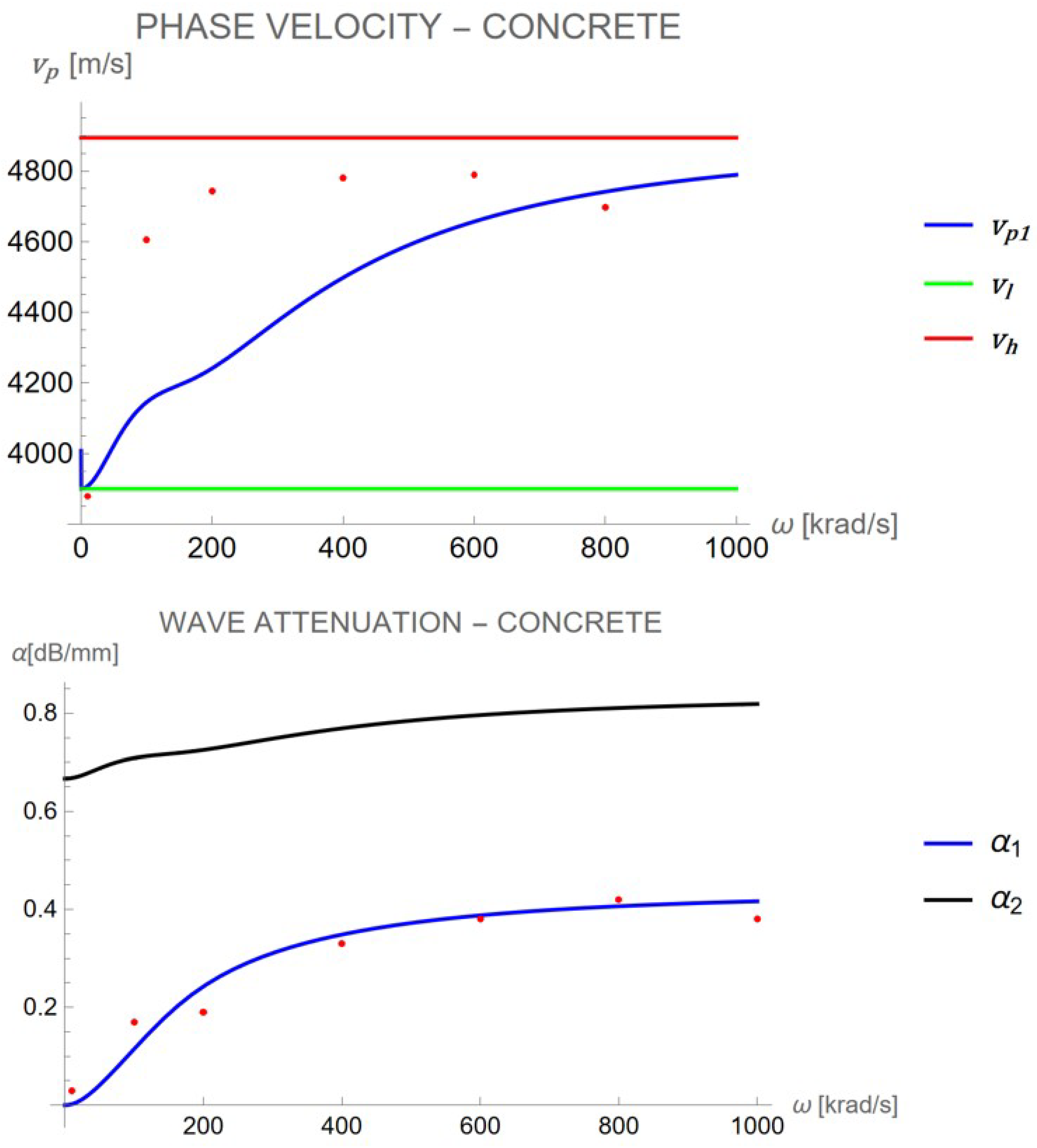

3.3.3. 3rd Case of Study: Concrete

As for the cement paste, the specimens tested were cubic of 150 mm edge, and the experimental setup was the same of previous case of study [

13]. Several different compositions of concrete were manufactured in function of water to cement ratio and of aggregate to cement ratio for a total of 24 specimens[

13]. We consider the data for a sample with ratio water/ciment=0.375 [

13]. Also in this case the model confirms the monotone trend of the experimental data[

13].

4. Conclusions

The limitations of classical methods for the dynamic identification of material constitutive parameters, as well as the need for simple and reliable models capable of interpreting both dissipation and dispersion phenomena in wave propagation, are well-known issues[

11]. Wave dispersion in materials under dynamic conditions has been extensively investigated in recent scientific literature [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Additionally, the effects of wave dissipation, starting from the wave amplitude value, have been the subject of many reference studies for this work[

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Once the wave propagation has been reconstructed in terms of both dispersion and attenuation, excluding singular points such as cavities or localized heterogeneities, we know the variation of the phase velocity and wave amplitudes across the entire frequency spectrum and can also characterize them in classical terms[

11,

13,

39,

40]. With this study we have formulated and validated a theoretical model that allows us to characterize, for a given material, both the dispersion and attenuation of the ultrasonic wave propagating through it, as well as all the key constitutive parameters associated with ultrasonic propagation (mechanical stiffness, microstructure, internal viscosity). The models has been constructed by applying the principle of Hamilton-Raylegh [

41,

42] and for the sake of simplicity, a one-dimensional model and only the longitudinal elastic modulus have been considered, whereas for the future a more in-depth investigation can take into account also 3D effects and therefore all the relevant elastic parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, De Fazio, N., Placidi,L., Fabbrocino, F., Luciano, R.; methodology, Placidi, L., Fabbrocino, F., Luciano, R.; software, De Fazio, N.; validation, De Fazio, N.; formal analysis, De Fazio, N.; investigation, De Fazio, N.; resources, De Fazio, N.; data curation, De Fazio, N.; writing—original draft preparation, De Fazio, N.; writing—review and editing, Placidi, L., Fabbrocino, F., Luciano, R.; visualization, Placidi, L.; supervision, Placidi, L.; project administration, Placidi, L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Legend of Symbols and Their Meanings

| Symbol |

Mean |

|

Action functional |

| K |

Kinetic energy density |

|

Potential energy density |

|

External energy |

| x |

Position in the reference configuration |

| t |

Time |

|

Two instants of time |

| L |

Length of the 1D model in the reference configuration |

|

Displacement field |

|

Standard material elastic modulus |

|

Non-standard strain gradient material elastic modulus |

|

Mass density |

|

Micro-inertia |

|

Concentrated forces applied at

|

|

Concentrated double forces applied at

|

|

Variation operator |

|

Distributed forces |

|

Distributed double forces |

|

Complex wave amplitude |

|

Wave number |

|

Wave number for right-hand direction propagative wave |

|

Wave frequency |

| i |

Imaginary unit |

| Re |

Real operator |

| Im |

Imaginary operator |

|

Plane wave velocity phase |

|

Low frequency regime velocity |

|

High frequency regime velocity |

|

Internal material viscosity related to first gradient field |

|

Internal material viscosity related to second gradient field |

| R |

Rayleigh function |

| Q |

Quality factor |

|

Damping ratio |

|

Attenuation coefficient |

References

- Aifantis, E.C. The Role of Gradient in the Mechanics of Materials. Journal of Elasticity 2003, 72, 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Steigmann, D.J. The mechanics of second-gradient materials. Journal of Elasticity 2002, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Germain, P. The Mechanics of Materials with Second-Order Gradients. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 1973, 21, 489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Eshelby, J.D. Elastic Inclusions and the Theory of Composite Materials. Journal of Elasticity 1980, 10, 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- Pendry, J.B. Metamaterials: The First Hundred Years. Science 2006, 314, 230–231. [Google Scholar]

- Bauchau, P. Ultrasonic Wave Propagation in Biological Tissues. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2001, 110, 2417–2424. [Google Scholar]

- Jafferis, J. Non-local Effects and Attenuation in Wave Propagation. Journal of Applied Physics 2015, 89, 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, D. Viscoelastic Effects in Second-Gradient Materials: A Theoretical Framework. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2017, 102, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, D. Non-Destructive Testing of Materials by Ultrasonic Waves; Springer, 2010.

- Hofmann, R. Frequency Dependent Elastic and Anelastic Properties of Clastic Rocks. Thesis degree by Colorado School of Mines 2006, p. 185.

- Lauwerier, H.A.; Koiter, W.T. North-Holland Series on Applied Mathematics and Mechanics. North-holland Series in Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 1967, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Humphrey, V.; Kim, B.N.; Yoon, S. Frequency dependencies of phase velocity and attenuation coefficient in a water-saturated sandy sediment from 0.3 to 1.0 MHz. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2007, 121, 2553–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippidis, T.; Aggelis, D. Experimental study of wave dispersion and attenuation in concrete. Ultrasonics 2005, 43, 584–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, B.; Marconi, E. Wave motion and dispersion phenomena: Veering, locking and strong coupling effects. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2012, 131, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Marzo, M.; Tomassi, A.; Placidi, L. A Methodology for Structural Damage Detection Adding Masses. Research in Nondestructive Evaluation 2024, 35, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, A. Dynamic Elastic Modulus Measurements in Materials; ASTM International, 1990.

- Giorgio, I.; Della Corte, A.; Dell’Isola, F. Dynamics of 1D nonlinear pantographic continua. Nonlinear Dynamics 2017, 88, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Bacciocchi, M.; Fantuzzi, N.; Luciano, R.; Fabbrocino, F. Computational simulation and acoustic analysis of two-dimensional nano-waveguides considering second strain gradient effects. Computers & Structures 2024, 296, 107299. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Fantuzzi, N.; Bacciocchi, M.; Fabbrocino, F.; Mousavi, M. Nonlinear wave propagation in graphene incorporating second strain gradient theory. Thin-Walled Structures 2024, 198, 111713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudato, M.; Barchiesi, E. , Non-linear dynamics of pantographic fabrics: modelling and numerical study. In Wave Dynamics, Mechanics and Physics of Microstructured Metamaterials: Theoretical and Experimental Methods; 2019; pp. 241–254.

- Nejadsadeghi, N.; Misra, A. Role of Higher-order Inertia in Modulating Elastic Wave Dispersion in Materials with Granular Microstructure. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2020, 185, 105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Isola, F.; Madeo, A.; Placidi, L. Linear plane wave propagation and normal transmission and reflection at discontinuity surfaces in second gradient 3D continua. ZAMM-Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 2012, 92, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dell’Isola, F.; Eugster, S.R.; Fedele, R.; Seppecher, P. Second-gradient continua: From Lagrangian to Eulerian and back. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids 2022, 27, 2715–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarchizadeh, N.; Laudato, M.; Manzari, L.; Abali, B.E.; Giorgio, I.; Bersani, A.M. Parameter identification of a second-gradient model for the description of pantographic structures in dynamic regime. Zeitschrift für angewandte Mathematik und Physik 2021, 72, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, I.; Andreaus, U.; Dell’Isola, F.; Lekszycki, T. Viscous second gradient porous materials for bones reconstructed with bio-resorbable grafts. Extreme Mechanics Letters 2017, 13, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, A.; Dell’Isola, F.; Darve, F. A continuum model for deformable, second gradient porous media partially saturated with compressible fluids. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2013, 61, 2196–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Isola, F.; Hutter, K. Variations of porosity in a sheared pressurized layer of saturated soil induced by vertical drainage of water. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1999, 455, 2841–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, R.; Barbero, E. Formulas for the stiffness of composites with periodic microstructure. International Journal of Solids and Structures 1994, 31, 2933–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocino, F.; Amendola, A. Discrete-to-continuum approaches to the mechanics of pentamode bearings. Composite Structures 2017, 167, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocino, F.; Carpentieri, G. Three-dimensional modeling of the wave dynamics of tensegrity lattices. Composite Structures 2017, 173, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciallella, A.; Giorgio, I.; Eugster, S.R.; Rizzi, N.L.; dell’Isola, F. Generalized beam model for the analysis of wave propagation with a symmetric pattern of deformation in planar pantographic sheets. Wave Motion 2022, 113, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchiesi, E.; Laudato, M.; Di Cosmo, F. Wave dispersion in non-linear pantographic beams. Mechanics Research Communications 2018, 94, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abali, B.E.; Vazic, B.; Newell, P. Influence of microstructure on size effect for metamaterials applied in composite structures. Mechanics Research Communications 2022, 122, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, G.; D’Annibale, F. On the role of different nonlinear damping forms in the dynamic behavior of the generalized Beck’s column. Nonlinear Dyn 2024, 112, 13733–13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placidi, L.; Di Girolamo, F.; Fedele, R. Variational study of a Maxwell–Rayleigh-type finite length model for the preliminary design of a tensegrity chain with a tunable band gap. Mechanics Research Communications 2024, 136, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezovski, A.; Giorgio, I.; Corte, A.D. Interfaces in micromorphic materials: wave transmission and reflection with numerical simulations. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids 2016, 21, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placidi, L.; Rosi, G.; Giorgio, I.; Madeo, A. Reflection and transmission of plane waves at surfaces carrying material properties and embedded in second-gradient materials. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids 2014, 19, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hima, N.; D’Annibale, F.; Dal Corso, F. Non-smooth dynamics of buckling based metainterfaces: rocking-like motion and bifurcations. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2023, 242, 108005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadan, V.K.; Varadan, V.V.; Ma, Y. Frequency-dependent elastic properties of rubberlike materials with a random distribution of voids. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1984, 76, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, G.; Placidi, L.; Auffray, N. On the validity range of strain-gradient elasticity: a mixed static-dynamic identification procedure. European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids 2018, 69, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dell’Isola, F.; Placidi, L. Variational principles are a powerful tool also for formulating field theories. International Research Centre on "Mathematics Mechanics of Complex Systems" M&MOCS, 2013.

- Abali, B.E. Revealing the physical insight of a length-scale parameter in metamaterials by exploiting the variational formulation. Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics 2019, 31, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).