Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Governing Equations

2.1.1. Bubble Dynamics in an Arbitrary Viscoelastic Medium Written in the Volume-Variation Framework

2.1.2. Bubble Dynamics in a Kelvin-Voigt Viscoelastic Medium Written in the Volume-Variation Framework

2.2. Numerical Solution of the Bubble Equation

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Model

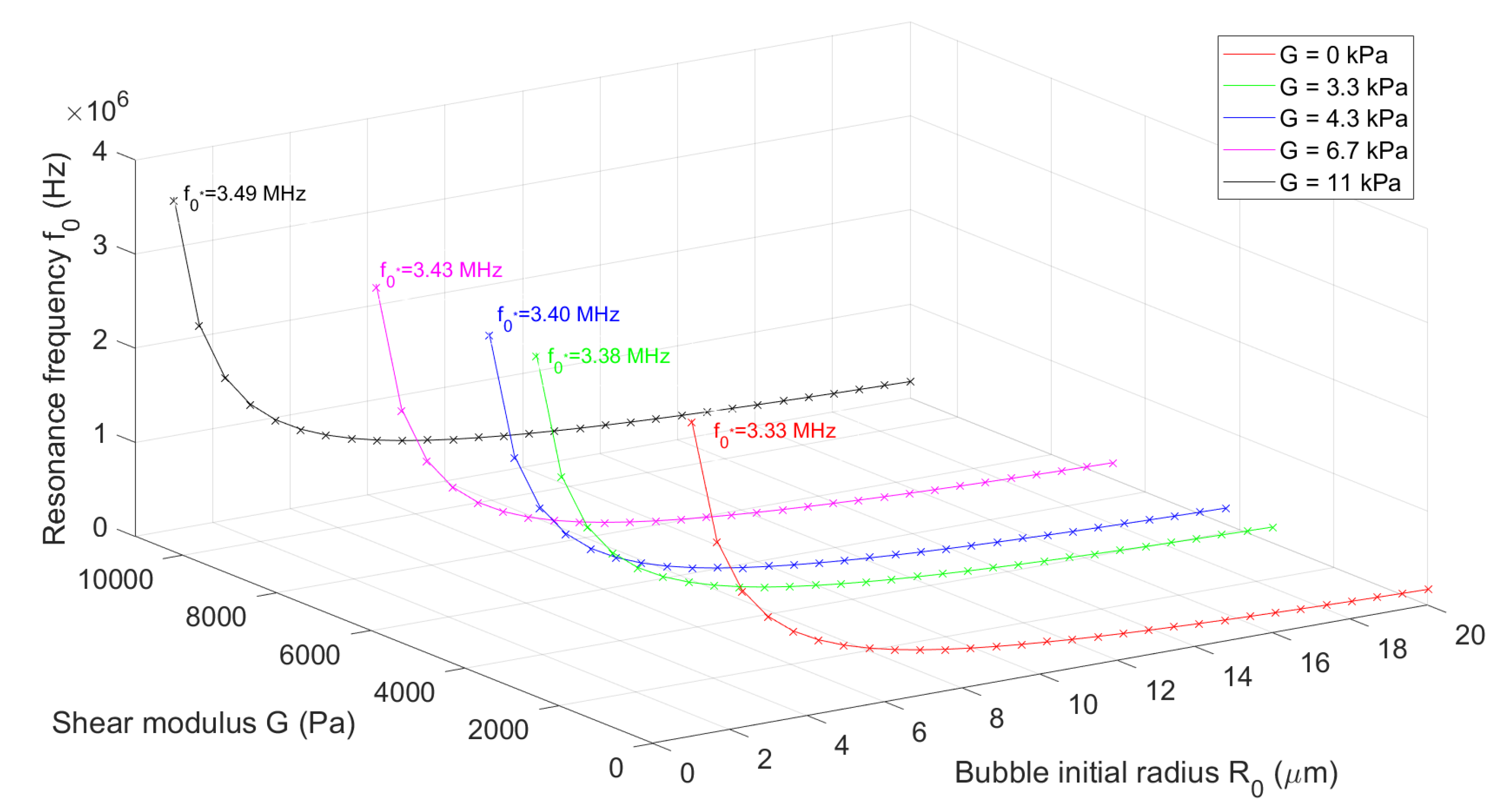

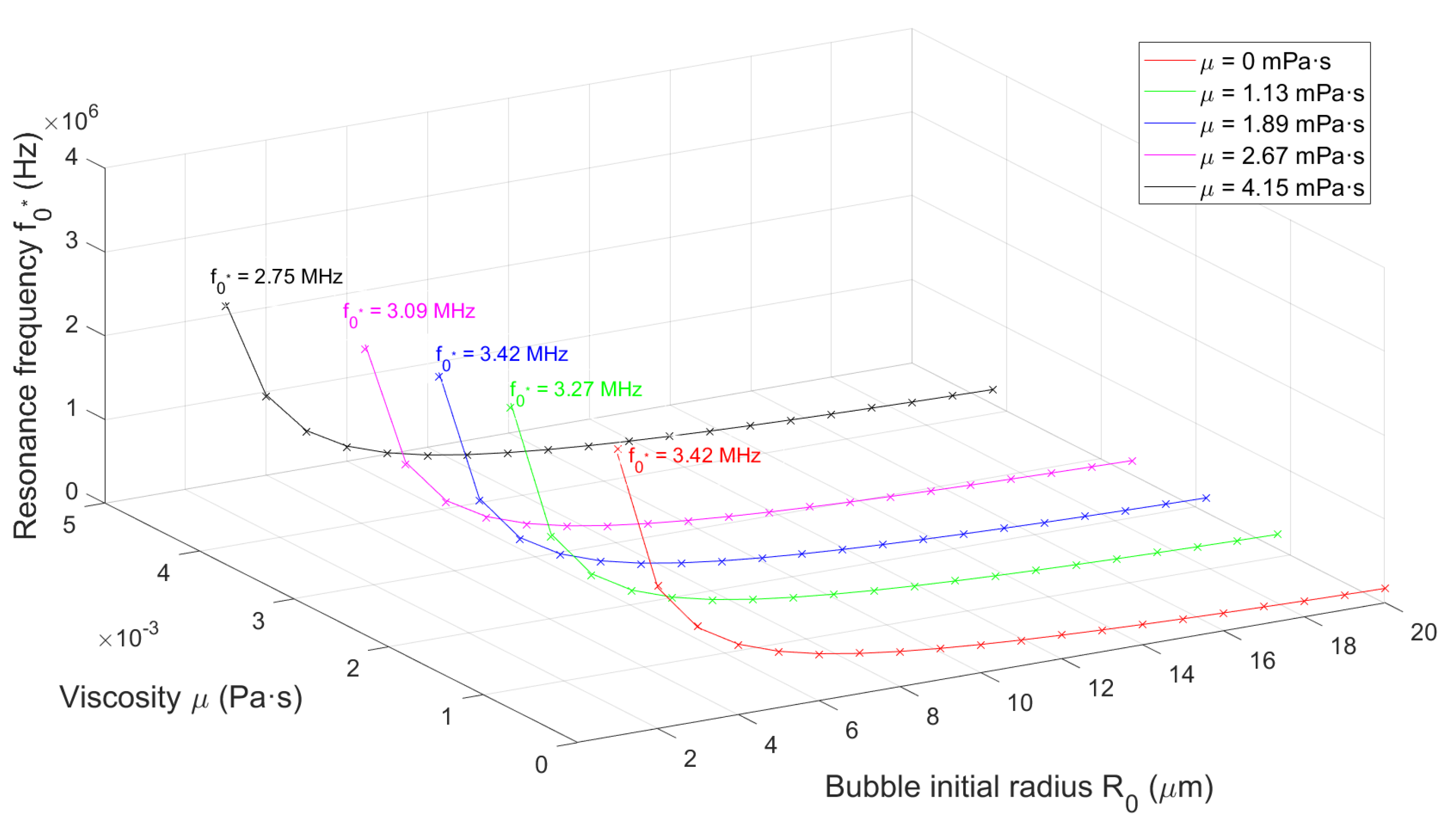

3.1.1. Effect of Elasticity and Viscosity on Bubble Resonance

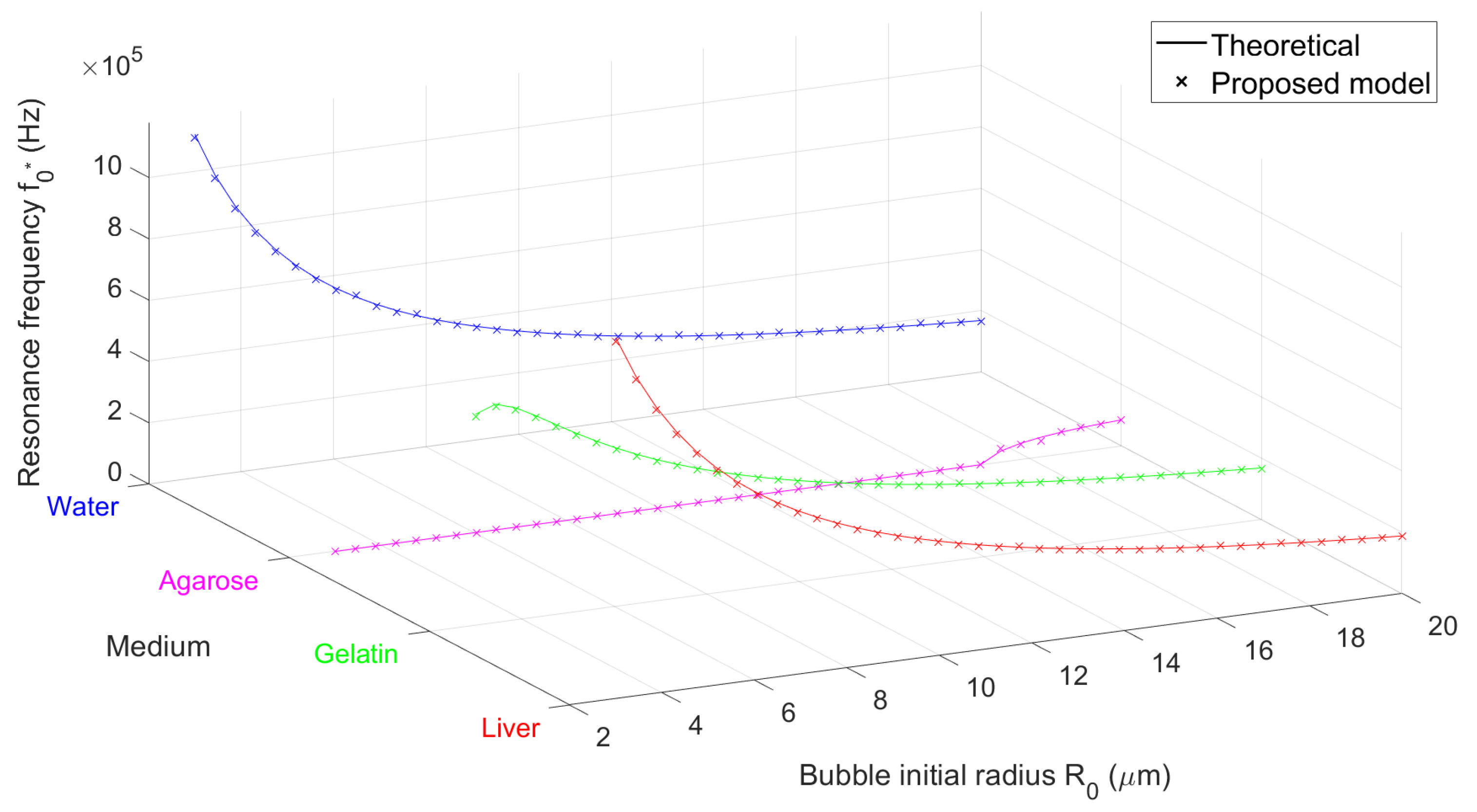

3.1.2. Bubble Resonance in Representative Soft Viscoelastic Media

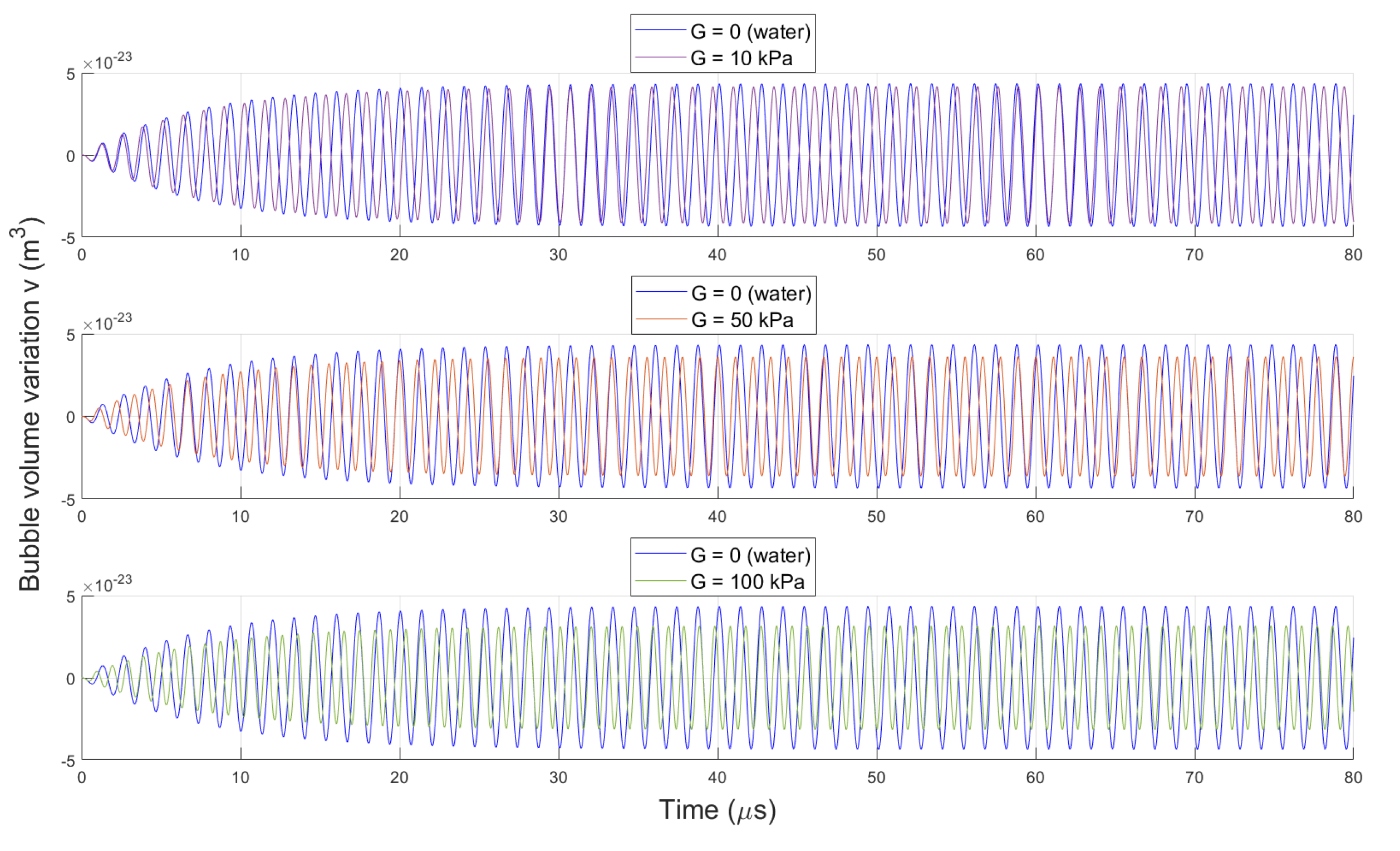

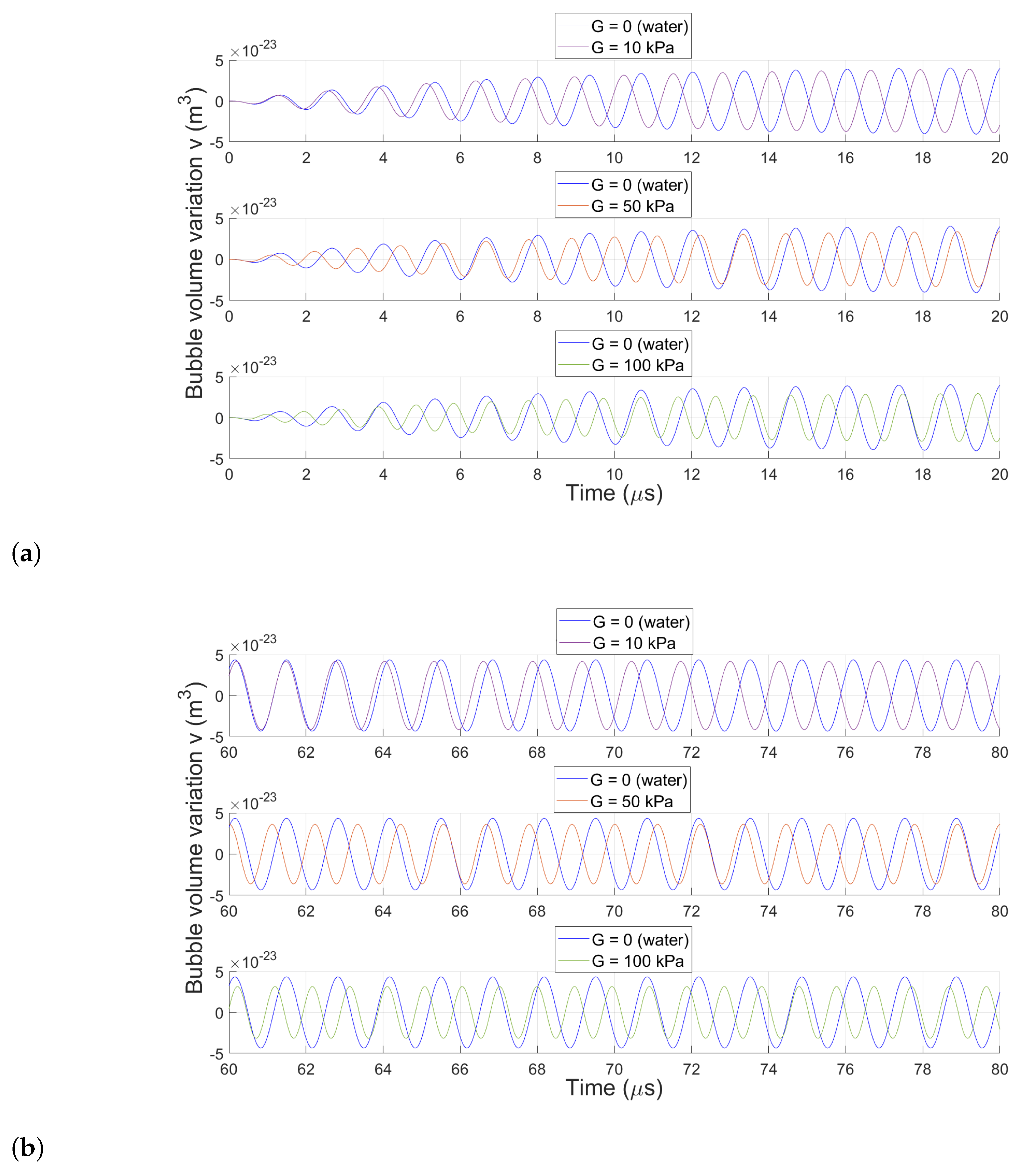

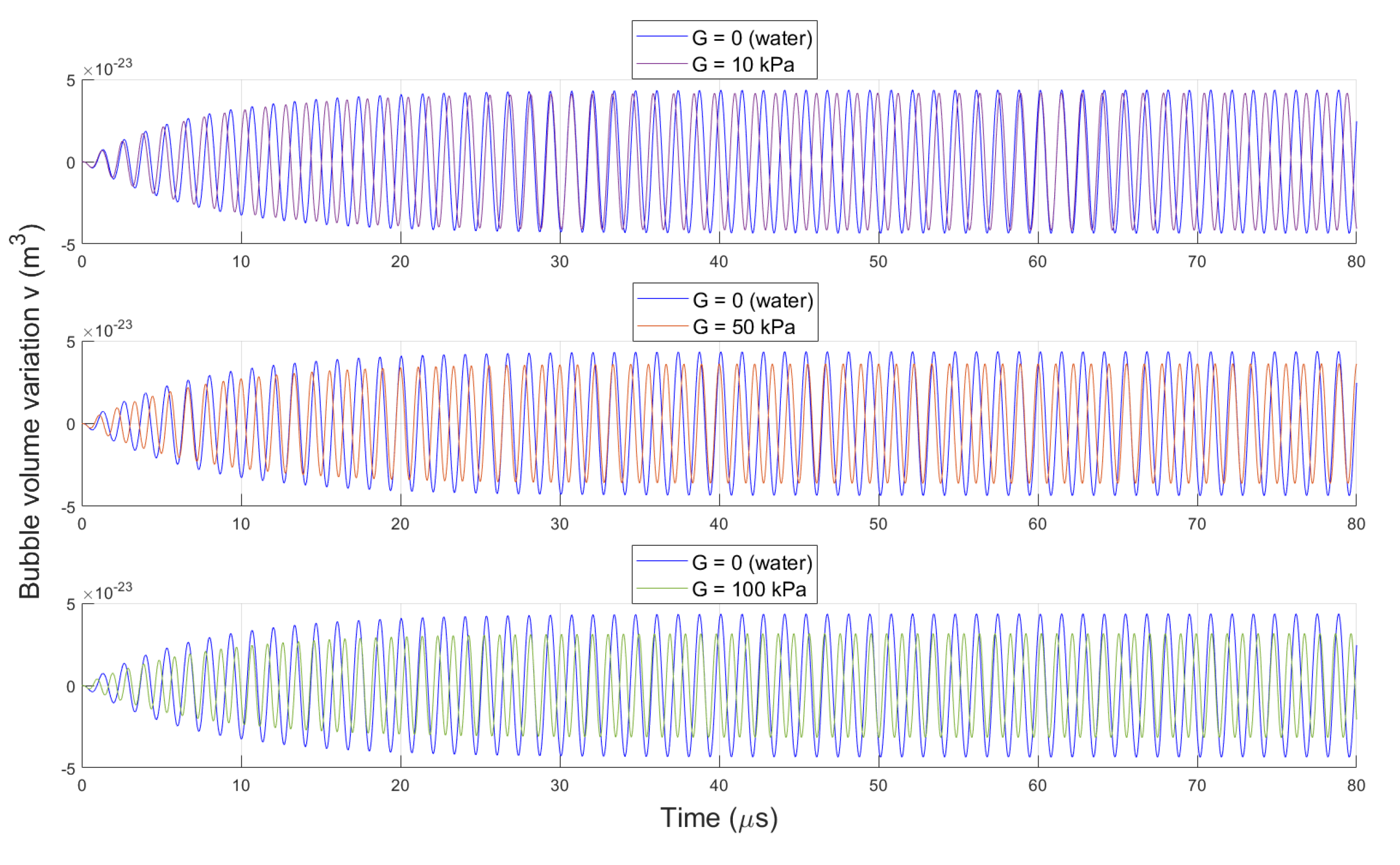

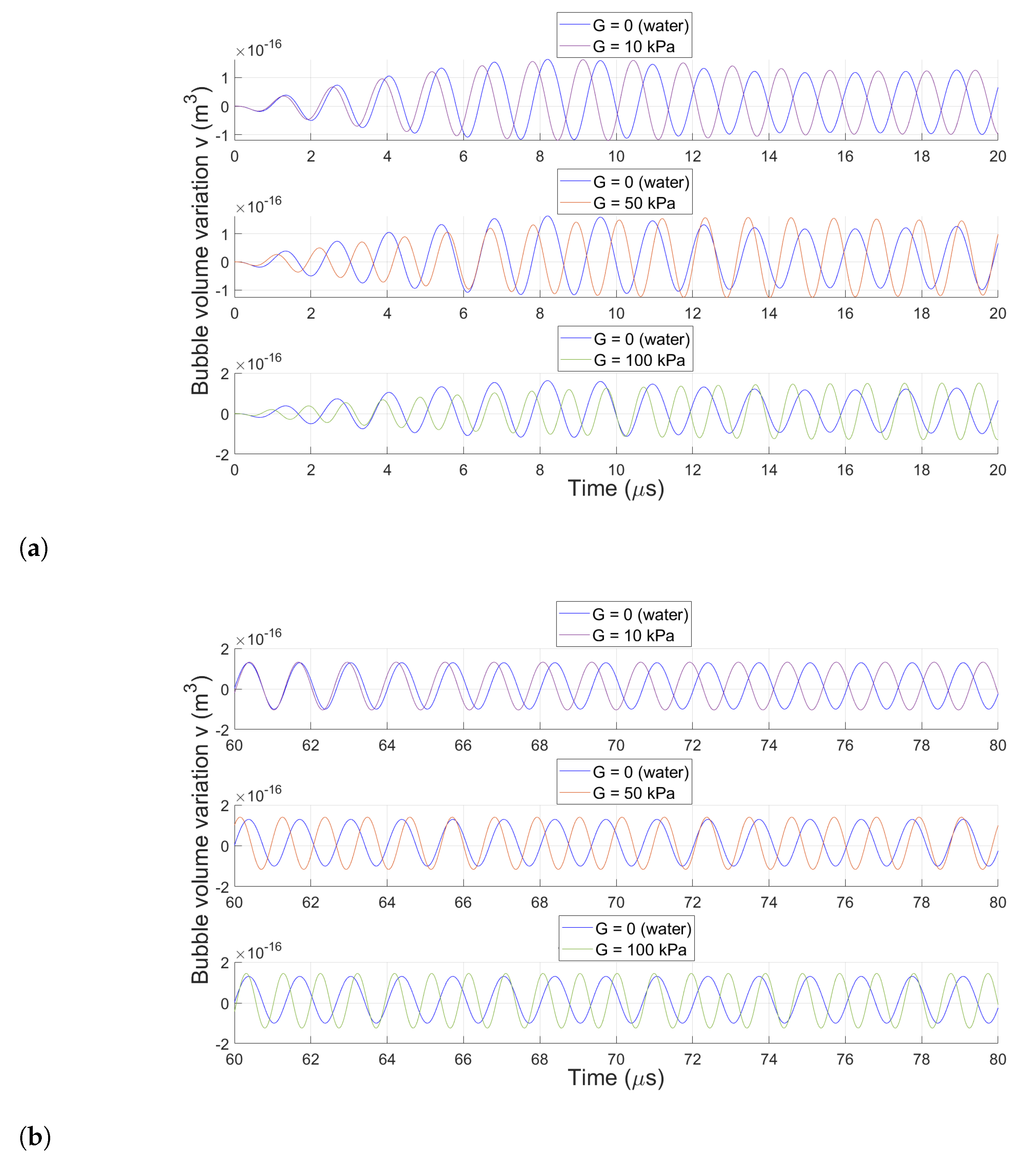

3.2. Bubble Volume Dynamics over Time

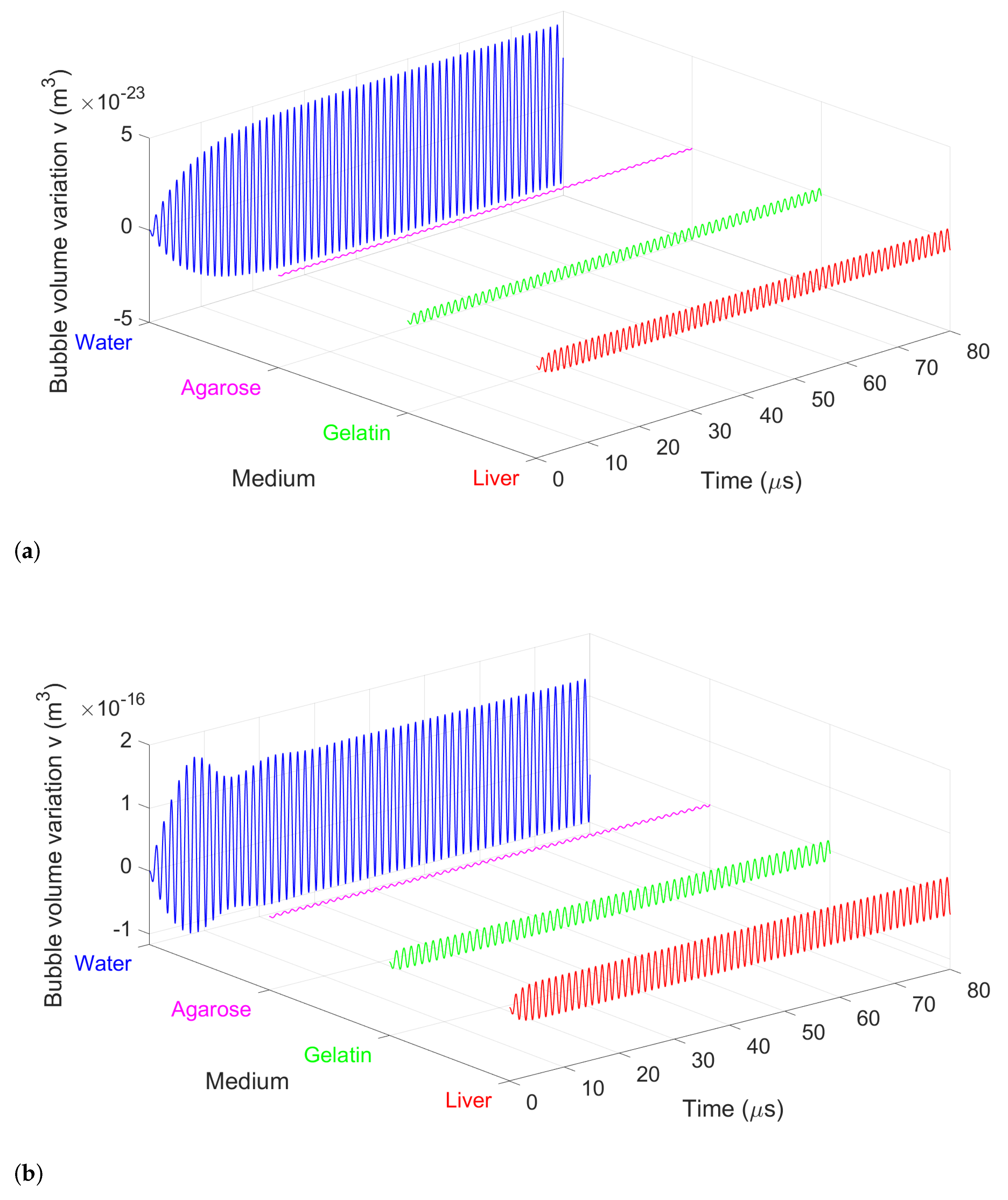

3.2.1. Bubble Volume Variation in Representative Soft Media

3.2.2. Effect of Medium Elasticity on Bubble Dynamics

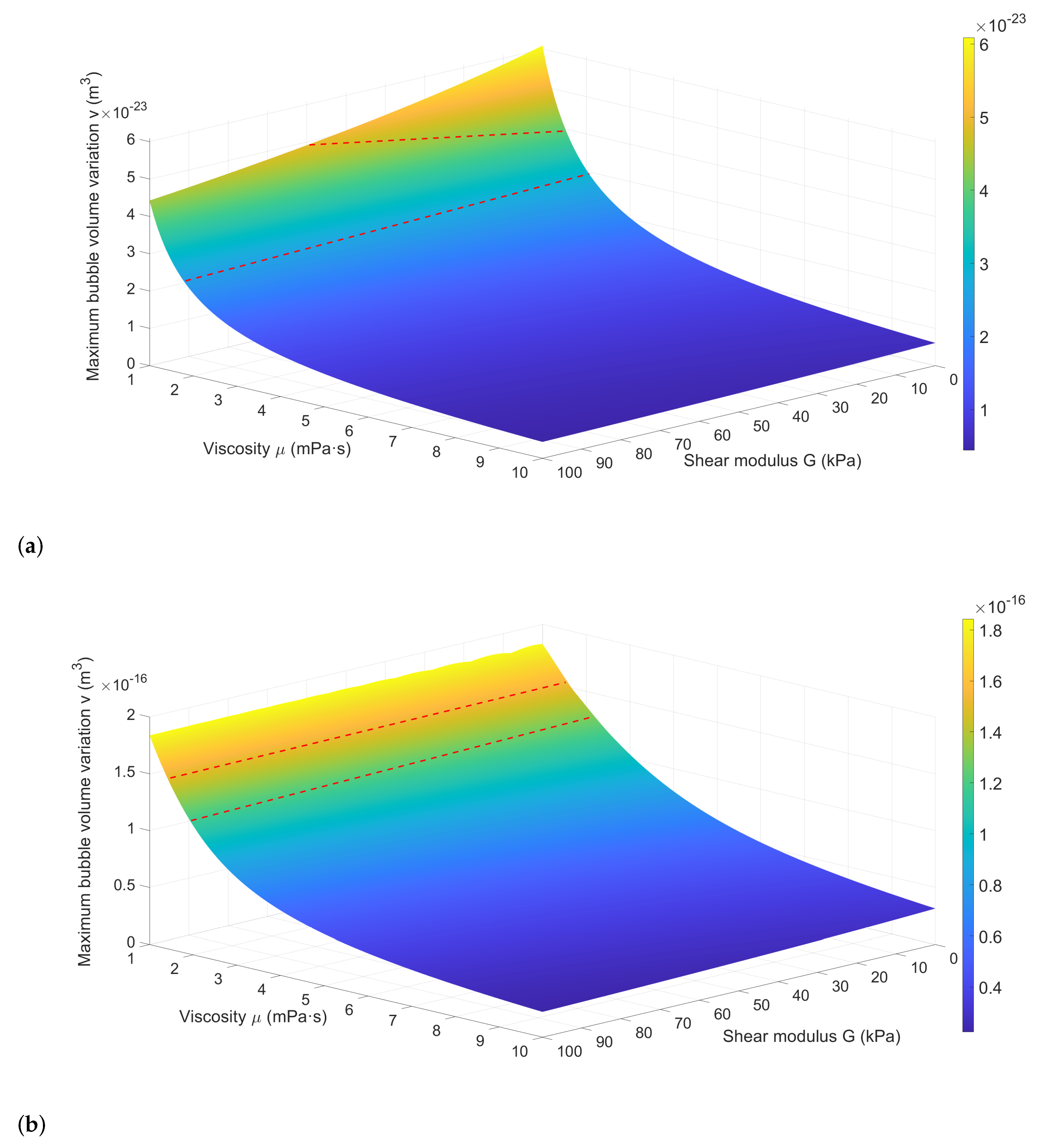

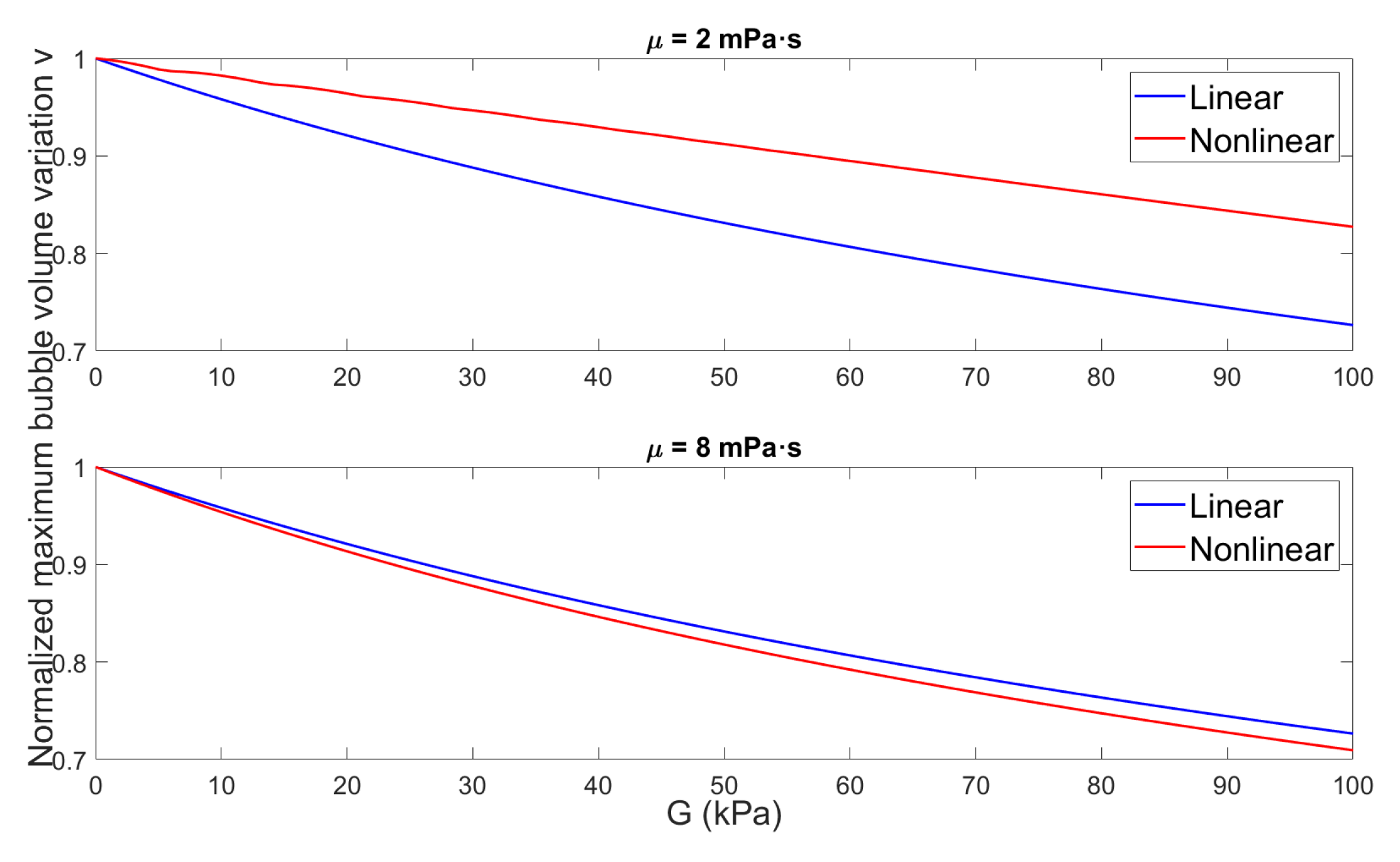

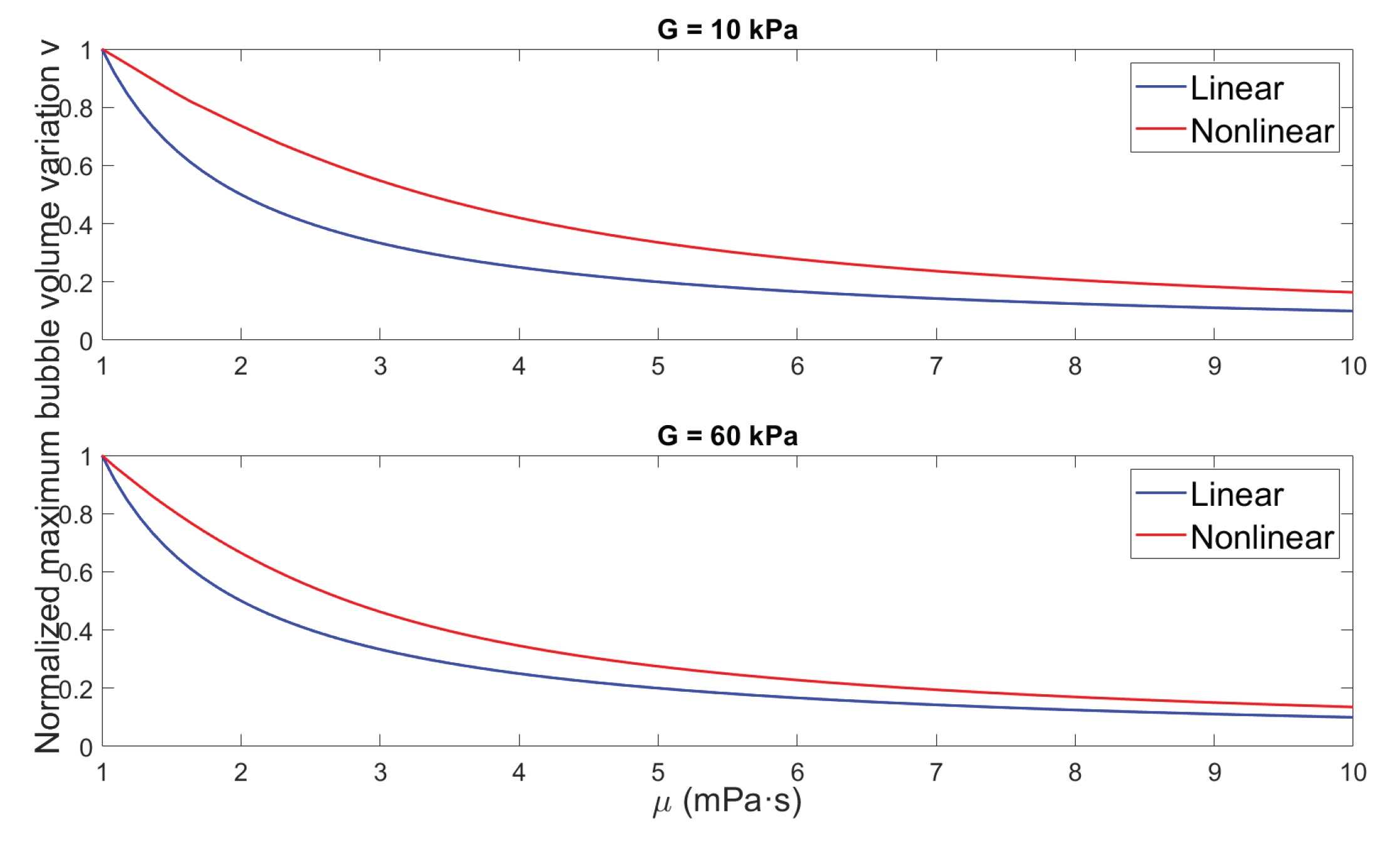

3.2.3. Bubble Behavior Across Shear Elasticity-Viscosity Parameter Space

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coussios, C.; Roy, R. Applications of Acoustics and Cavitation to Noninvasive Therapy and Drug Delivery. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2008, 40, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, T.; Chu, J.K.; Tan, K.W. Advancements in Acoustic Cavitation Modelling: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions in Sonochemical Reactor Design. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2025, 112, 107163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, T. The acoustic bubble; Academic press, 2012.

- Allen, J.; Roy, R. Dynamics of gas bubbles in viscoelastic fluids. II. Nonlinear viscoelasticity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2000, 108, 1640–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamburidze, A.; De Corato, M.; Huerre, A.; Pommella, A.; Garbin, V. High-frequency linear rheology of hydrogels probed by ultrasound-driven microbubble dynamics. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 3946–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Zou, J. Minnaert Resonances for Bubbles in Soft Elastic Materials. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 2022, 82, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.; Roy, R.; Crum, L. Artificial Bubble Cloud Targets for Underwater Acoustic Remote Sensing. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 1995, 12, 1287–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.B.; Miksis, M. Bubble oscillations of large amplitude. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1980, 68, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogler, H.; Goddard, J. Collapse of spherical cavities in viscoelastic fluids. Physics of Fluids 1970, 13, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasawa, I.; Yang, W.J. Dynamic behavior of a gas bubble in viscoelastic liquids. Journal of Applied Physics 1970, 41, 4526–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Roy, R. Dynamics of gas bubbles in viscoelastic fluids. I. Linear viscoelasticity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2000, 107, 3167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Church, C.C. A model for the dynamics of gas bubbles in soft tissue. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2005, 118, 3595–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, C.; Johnsen, E. Nonlinear oscillations following the Rayleigh collapse of a gas bubble in a linear viscoelastic (tissue-like) medium. Physics of Fluids 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnez, M.T.; Johnsen, E. Numerical modeling of bubble dynamics in viscoelastic media with relaxation. Physics of Fluids 2015, 27, 063103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilonova, E.; Solovchuk, M.; Sheu, T. Bubble dynamics in viscoelastic soft tissue in high-intensity focal ultrasound thermal therapy. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2018, 40, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonets, T.; Solovchuk, M. GPU-accelerated study of the inertial cavitation threshold in viscoelastic soft tissue using a dual-frequency driving signal. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2022, 88, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Yamakawa, Y.; Zhao, J.; Johnsen, E.; Ando, K. Ultrasound-induced nonlinear oscillations of a spherical bubble in a gelatin gel. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2021, 924, A38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudron, R.; Warnez, M.T.; Johnsen, E. Bubble dynamics in a viscoelastic medium with nonlinear elasticity. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2015, 766, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. VIII. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Philosophical Magazine Series 1 1917, 34, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperetti, A. A generalization of the Rayleigh–Plesset equation of bubble dynamics. The Physics of Fluids 1982, 25, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterborn, W. Numerical investigation of nonlinear oscillations of gas bubbles in liquids. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1976, 59, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabolotskaya, E.; Soluyan, S. A POSSIBLE APPROACH TO AMPLIFICATION OF SOUND WAVES, 1967.

- Zabolotskaya, E.A.; Soluyan, S.I. EMISSION OF HARMONIC AND COMBINATION-FREQUENCY WAVES BY BUBBLES. 1973.

- Ilinskii, Y.A.; Zabolotskaya, E.A. Cooperative radiation and scattering of acoustic waves by gas bubbles in liquids. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1992, 92, 2837–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhille, C. A fourth-order approximation Rayleigh-Plesset equation written in volume variation for an adiabatic-gas bubble in an ultrasonic field: Derivation and numerical solution. Results in Physics 2021, 25, 104193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, T. The Rayleigh–Plesset equation in terms of volume with explicit shear losses. Ultrasonics 2008, 48, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, K.S.; Lee, K.M.; Wilson, P.S.; Wochner, M.S. On the resonance frequency of an ideal arbitrarily-shaped bubble. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 2014, 20, 045004. [Google Scholar]

- Dollet, B.; Marmottant, P.; Garbin, V. Bubble Dynamics in Soft and Biological Matter. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2019, 51, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catheline, S.; Gennisson, J.L.; Delon, G.; Fink, M.; Sinkus, R.; Abouelkaram, S.; Culioli, J. Measurement of viscoelastic properties of homogeneous soft solid using transient elastography: An inverse problem approach. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2004, 116, 3734–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.H.; Fink, K.D.; et al. Numerical methods using MATLAB; Vol. 4, Pearson prentice hall Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2004.

- Hasegawa, T.; Kanagawa, T. Effect of liquid elasticity on nonlinear pressure waves in a visco-elastic bubbly liquid. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35, 043309. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Wu, P. Multi-bubble scattering acoustic fields in viscoelastic tissues under dual-frequency ultrasound. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 99, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, J. Numerical studies of bubble pulsation in viscoelastic media under dual-frequency ultrasound. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2024, 2822, 012151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilonova, E.; Solovchuk, M.; Sheu, T. Dynamics of bubble-bubble interactions experiencing viscoelastic drag. Physical Review E 2019, 99, 023109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, P.; Liang, H. Medical ultrasound: Imaging of soft tissue strain and elasticity. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface / the Royal Society 2011, 8, 1521–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crha, J.; Orvalho, S.; Ruzicka, M.C.; Shirokov, V.; Jerhotová, K.; Pokorny, P.; Basařová, P. Bubble formation and swarm dynamics: Effect of increased viscosity. Chemical Engineering Science 2024, 288, 119831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagami, S.; Kanagawa, T. Weakly nonlinear focused ultrasound in viscoelastic media containing multiple bubbles. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 97, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Zou, Q.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z. Effects of medium viscoelasticity on bubble collapse strength of interacting polydisperse bubbles. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 95, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, A.D.; Cain, C.A.; Hall, T.L.; Fowlkes, J.B.; Xu, Z. Probability of Cavitation for Single Ultrasound Pulses Applied to Tissues and Tissue-Mimicking Materials. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2013, 39, 449–465. [Google Scholar]

- Husseini, G.A.; de la Rosa, M.A.D.; Richardson, E.S.; Christensen, D.A.; Pitt, W.G. The role of cavitation in acoustically activated drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2005, 107, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaykanat, S.I.; Uguz, A.K. The role of acoustofluidics and microbubble dynamics for therapeutic applications and drug delivery. Biomicrofluidics 2023, 17, 021502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Medium (soft biological tissue) | Shear modulus G (kPa) |

|---|---|

| Without shear elasticity | 0 |

| Fat | 3.3 |

| Liver | 4.3 |

| Muscle | 6.7 |

| Glandular breast | 11 |

| Medium | Viscosity () |

|---|---|

| GLY00 | 0.00 |

| GLY04 | 1.13 |

| GLY25 | 1.89 |

| GLY35 | 2.67 |

| GLY47 | 4.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).