1. Introduction

Fusicolla spp. are ascomycetous fungi of to the order Hypocreales and the family Nectriaceae [

1]. The genus

Fusicolla was originally established by Bonorden [

1], typified by

F. betae (Desm.) Bonord. and was later subjected to taxonomic revision by Gräfenhan et al. [

2]. The majority of species in this genus are saprobes, obtaining nutrients from the decomposition of organic matter. They are therefore found on a wide range of substrates, including wild boar bones [

3], decaying wood [

4,

5], water [

6], air [

7], soil [

8], and rotten twigs [

8,

9].

Fusicolla is characterised by perithecia that are scattered to gregarious, spherical to pyriform, yellowish or pale buff to orange, and smooth walled. They are partly or completely immersed in a slimy, orange hyphal sheet. The cylindrical to narrowly clubbed asci contain eight hyaline to pale brown 1-septate ascospores. The formation of falcate, straight to curved, septate macroconidia and sparse or absent, ellipsoid to allantoid, aseptate microconidia are also observed [

9,

10]. Currently, 41 species are classified in this genus [

11].

A recent study investigating the fungal community structure of soils with heterogeneous pollution profiles led to the isolation of a novel Fusicolla species from a sample contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). This fungus was characterised using a comprehensive and holistic approach, combining macroscopic and microscopic morphological observations, and genetic analysis. The four barcode genetic regions were sequenced and analysed: the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS), a fragment of the β-tubulin gene (tub2), the gene for the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (rpb2), and the D1/D2 region of the large ribosomal DNA subunit (LSU). By comparing these sequences with those of known and species-type strains of Fusicolla, we were able to confirm the novelty of the isolate. The aim of this study was to formally describe and characterise this new species of Fusicolla, both genetically and phenotypically.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains and Macroscopic Characterisation

The genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. were compared with those of three established and available type strains, F. sporellula CBS 110191, F. meniscoidea CBS 110189, and F. acetlilerea CBS 123378. To characterise temperature growth profiles and colony morphology, including macroscopic features, surface/reverse aspects, and time of growth, all fungal strains were cultured on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar supplemented with gentamicin and chloramphenicol (SDAGC2) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates for seven to ten days at various temperatures of 4 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, 37 °C, and 56 °C.

2.2. Soil Sample

The soil sampled was collected from a former railway site where creosote, a mixture of tar-derived oils with fungicidal properties, had been applied. Creosote consists of 85% polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The soil was characterised by a total organic content (TOC) of 0.89% and the sum of the concentrations of the 16 PAHs listed by the United States Environmental Agency (US EPA) was 3.8 mg/kg.

2.3. Microscopic Characterisation

The initial assessment of microscopic characteristics was made by light microscopy. Microscopic slides were prepared for observation using cellophane tape mounts with lactophenol cotton blue (LCB) staining. Photographs were taken using a DM 2500 camera (Leica Camera SARL, Paris, France). Further characterisation was then carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Freshly grown colonies were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, kept at 4°C for over 2 hours, then deposited on glass slides by cytocentrifugation for 8 minutes at 800 rpm and air dried. High-resolution micrographs were taken using a TM4000PlusII tabletop SEM (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with the Backscattered Electron (BSE) detector, in objective mode 3, at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV and magnifications ranging from 250x to 1200x. The acquisition settings appear on each micrograph in the following order: Instrument, acceleration voltage, magnification, working distance, detector, scale bar.

2.4. MALDI-TOF MS Identification

Fungal strains were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) supplemented with gentamycin and chloramphenicol (GC) at 25 °C for seven days. After incubation, colonies were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) according to the protocol described by Cassagne et al. (2016) [

12]. Analyses were performed using the Microflex LT™ instrument and the MALDI Biotyper™ system (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany), using both the manufacturer’s reference mass spectra database and an in-house reference database. We have expanded our in-house reference database to include the mass spectra of the CBS type strains acquired from the

Fusicolla collection CBS type strains, as well as the novel

Fusicolla species.

2.5. Antifungal Susceptibility Tests

In vitro susceptibility testing was performed using the Etest gradient strip method (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the Fusicolla strain to five antifungal drugs: amphotericin B, posaconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole and isavuconazole, on RPMI agar plates (bioMérieux) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MICs were determined as the lowest concentrations of the antimicrobial agent that completely inhibited visible growth of the strains tested in mg/L (bioMérieux).

2.6. BiologTM Phenotypic Microarray Analysis

We used Gen III Biolog FF MicroPlates™ (Biolog Hayward, CA, USA) to perform a comprehensive and rapid assessment of fungal carbon source assimilation and metabolic profiling. The BioLog FF MicroPlates™, with their extensive range of carbon sources, facilitate the phenotypic differentiation of fungal isolates. The microplates contain prefilled and dried nutrient substrates in each of the 96 wells, along with redox dyes (tetrazolium) and colorimetric indicators. The Fusicolla strains were cultivated on 2% malt extract agar (MEA) for a period of 5-7 days until well developed and fresh colonies were observed. A standardised fungal suspension was prepared by swabbing conidia into the FF Inoculating Fluid™ and adjusted to a 75-80% transmittance using a Biolog Turbidimeter™ (Cat. No. 3587). Then, 100 µL of the fungal suspension was added to each well of the FF MicroPlates™. The plates were incubated at 30°C for a period of seven days. Utilisation of different carbon sources was indicated by a colour change, and the resulting phenotypic fingerprint was analysed as comparative growth curves under diffrent nutrient conditions.

2.7. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sanger Sequencing

After seven days of incubation period on SDA GC at 25 °C, the DNA was extracted from the grown colonies using the Qiagen™ Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The first mechanical lysis step was performed using the FastPrep™-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) and NUCLISENS™ easyMAG™ lysis buffer (bioMérieux, SA) in bead-containing Matrix E tubes (MP Biomedicals). DNA was then extracted using the EZ1 Advanced XL™ instrument (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Four genomic regions were identified for PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing. The following genomic regions were targeted for PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing: the internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 of the ribosomal RNA gene (ITS1-2), the D1/D2 domains of the large subunit ribosomal RNA gene (LSU), a partial fragment of the β-tubulin gene (B-tub2), and a fragment of the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) (

Table 1, references [

13,

14,

15,

16]). PCR amplification was performed using a 25 µL reaction mixture containing 12.5 µL AmpliTaq Gold™ 360 Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.75 µL each of forward and reverse primers, 6 µL sterile DNase/RNase-free water, and 5 µL template DNA. The cycling programme for all amplifications consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 39 cycles of: denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute, an annealing step at 56°C for 30 seconds, an extension step at 72°C for 1 minute, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes to complete the programme. The amplified DNA was purified and sequenced on a 3500 Genetic Analyzer™ (Applied Biosystems). The generated sequences were then assembled and corrected using Chromas Pro 1.34 software. Finally, sequence homology searches were performed using the BLASTn algorithm against the reference nucleotide sequences available in the Nucleotide GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

2.8. Phylogenetic Analysis

Five phylogenetic trees were constructed to determine the phylogenetic relationships of the novel

Fusicolla species. The first phylogenetic tree was constructed using a multilocus approach, concatenating the nucleotide sequences of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS), the D1/D2 domains of the large subunit ribosomal RNA (LSU) gene, the beta-tubulin (B-tub2) gene and the RNA polymerase II (RPB2) gene for the novel soil isolate, three reference CBS strains and additional

Fusicolla species retrieved from the GenBank database (

Table 2). The remaining four trees were constructed using a single locus each and also included several Fusicolla species retrieved from the GenBank database. All sequences were aligned using the integrated Muscle tool within the MEGA 11 software package [

13]. The following species were used as outgroups for all tree constructions:

Corallomycetella repens CBS 358.49,

Stylonectria applanata CBS 125489,

Stylonectria wegeliniana CBS 125490 and

Clonostachys rosea CBS 154.27. Maximum parsimony phylogenetic trees were generated using the default settings in MEGA version 11. To assess branch support, 1000 bootstrap analyses were performed.

3. Results

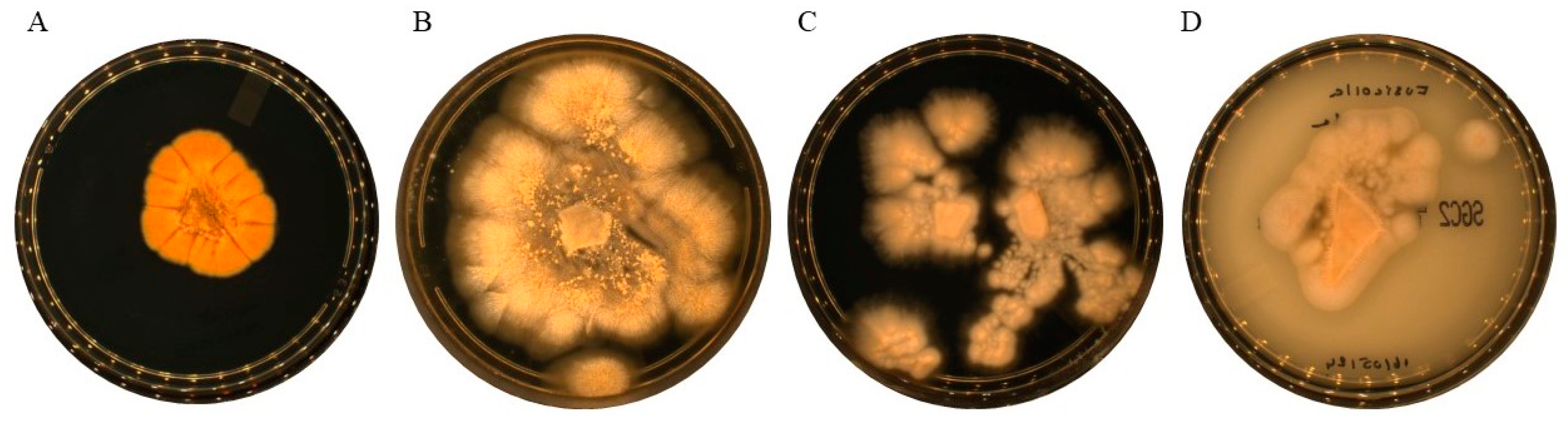

3.1. Macroscopic Characterisation

Macroscopic characteristics confirmed the rapid growth time within four to five days of the

Fusicolla species on SDA GC and PDA media at an optimal temperature of 25°C for all species (

Figure 1). However, none of the four species showed growth at temperatures of 4, 37 or 56°C. Colonies of the three reference isolates had a white-beige luteous colouration with pale buff centres, observed on both the surface and back. In contrast, the new

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. showed a distinct chrome yellow to orange colouration. After a period of 21 to 25 days,

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. underwent a colour change from light orange to pale brownish. It is noteworthy that with the exception of

Fusicolla acetilerea (CBS 123378) and

Fusicolla meniscoidea (CBS 110189), the remaining isolates had a flat and moist appearance. Both

Fusicolla sporellula (CBS 110191) and the newly isolated

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. had a smooth, glabrous and slightly hairy morphology. In contrast,

F. meniscoidea had a slightly gelatinous or sticky, membranous to mucilaginous consistency with subtle aerial mycelial growth.

F. acetilerea, on the other hand, had a slightly slimy or mucilaginous texture, accompanied by prominent aerial mycelium.

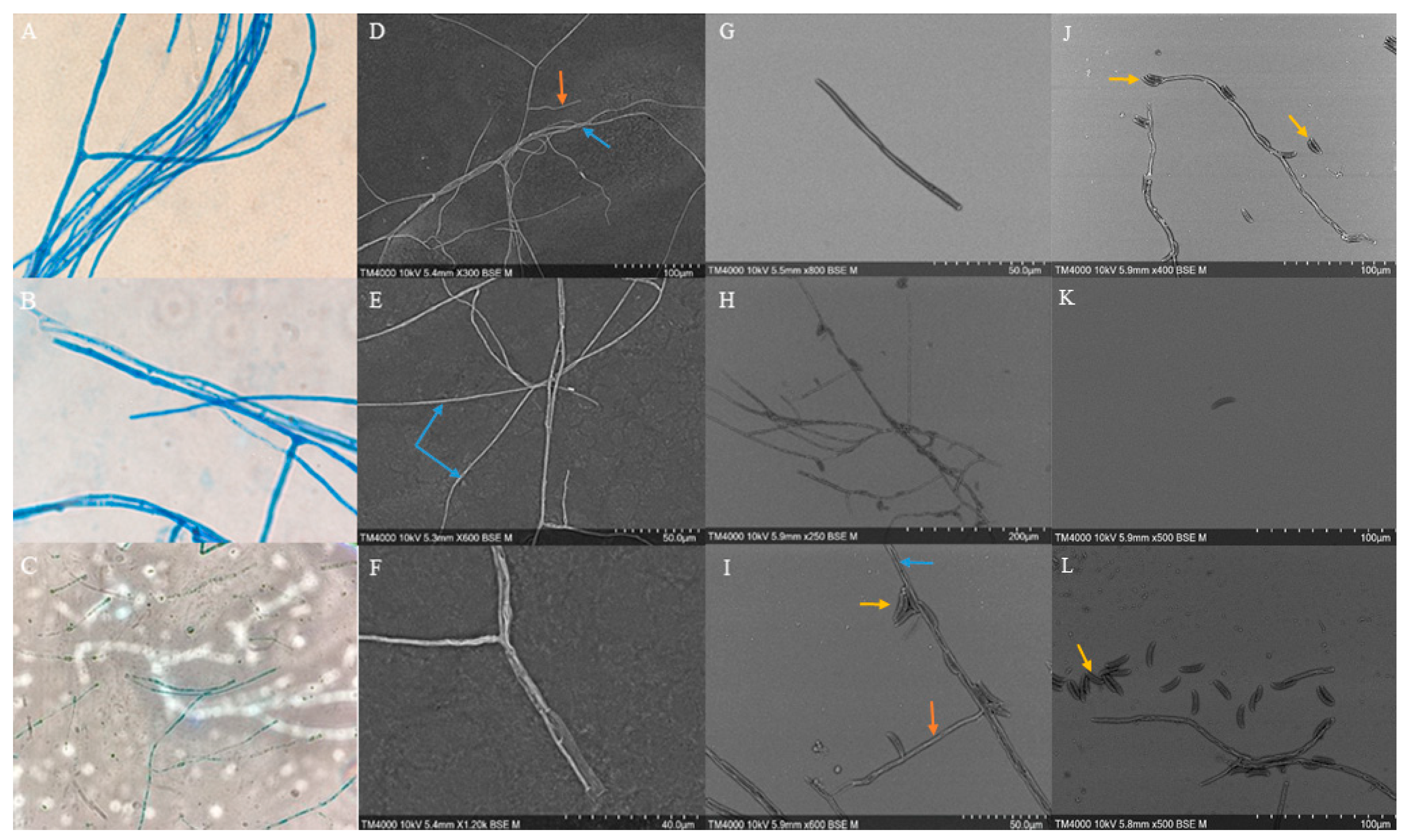

3.2. Microscopic Characteristion

Microscopic examination of

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. revealed the presence of long, thread-like hyaline hyphae with smooth walls and septate structures (blue arrows) (

Figure 2D–F,H–J,L). The conidiophores originated directly from the somatic hyphae, which were sparsely branched (blue arrows) (

Figure 2: panels D, F, H, J, and L). It was observed that the conidiophores rarely bore terminal and lateral phialidic conidiogenous cells. Microconidia showed a tendency to aggregate and were observed exclusively in colonies grown on PDA, while no such structures were observed on SDA (yellow arrows) (

Figure 2: panels I & L). It should be noted that macroconidial structures were only rarely observed (

Figure 2: panel G).

3.3. MALDI-TOF MS Identification

The MALDI-Biotyper™ (Bruker Daltonics) MALDI-TOF MS identification log score was below the 1.70 threshold required for reliable identification at the species level. The isolate was identified as a member of the genus Fusicolla by DNA sequencing. The mass spectra of the novel Fusicolla isolate were subsequently added to the MALDI-TOF MS reference database and integrated with the mass spectra of the three reference strains from the CBS collection: Fusicolla acetilerea CBS 123378, Fusicolla meniscoidea CBS 110189, and Fusicolla sporellula CBS 110191.

3.4. Physiological/Phenotypic Analysis with the BiologTM System

The Biolog™ advanced phenotyping technology proved to be a highly effective solution for the phenotypic characterisation of isolates. The results of the oxidation and assimilation assays are shown in

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. The metabolic profile performed on Biolog FF plates showed that Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. Fo821 metabolised certain metabolic substrates, including sugars, amino acid derivatives and organic acids, more extensively and more rapidly than

F. acetilerea,

F. sporellula and

F. meniscoidea. The observed differences in metabolic profiles indicate a distinct preference or efficiency of this new species for these nutrient substrates. This suggests the possibility of differences in metabolic pathways or affinity for specific substrates between the different species.

3.5. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

The MIC for amphotericin B in

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. was 0.94 mg/L, indicating susceptibility to this antifungal drug. In contrast, the MICs for ITC, POS, VOR and IVU were all above 32 mg/L, indicating a resistance profile to azole antifungals (

Table 3).

3.6. DNA Sequence-Based Identification

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS), large ribosomal subunit (LSU) D1D2 domains, β-tubulin gene fragment (β-tub2), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit gene (RPB2) and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1-α) regions of the fungal isolate were sequenced and BLASTn searched against the NCBI GenBank database. The results showed that none of the sequences obtained had a percentage identity of 99% or more with previously deposited sequences from type materials. It is worth noting that the closest identity matches were: for ITS, 97.36% identity with Fusicolla elongata CBS 148934 (NR182510.1), for LSU, 98.71% identity with Fusicolla quarantenae URM 94407 (NG008200.1), for β-tub, 96.4% identity with Fusicolla ossicola CBS 140161 (MW834307.1), for RPB2, 92.62% identity with Fusicolla acetilerea BBA 63789 (HQ897701.1), and for TEF-1a, 86.81% identity with Fusicolla quarantenae 111JB with (MW556625.1).

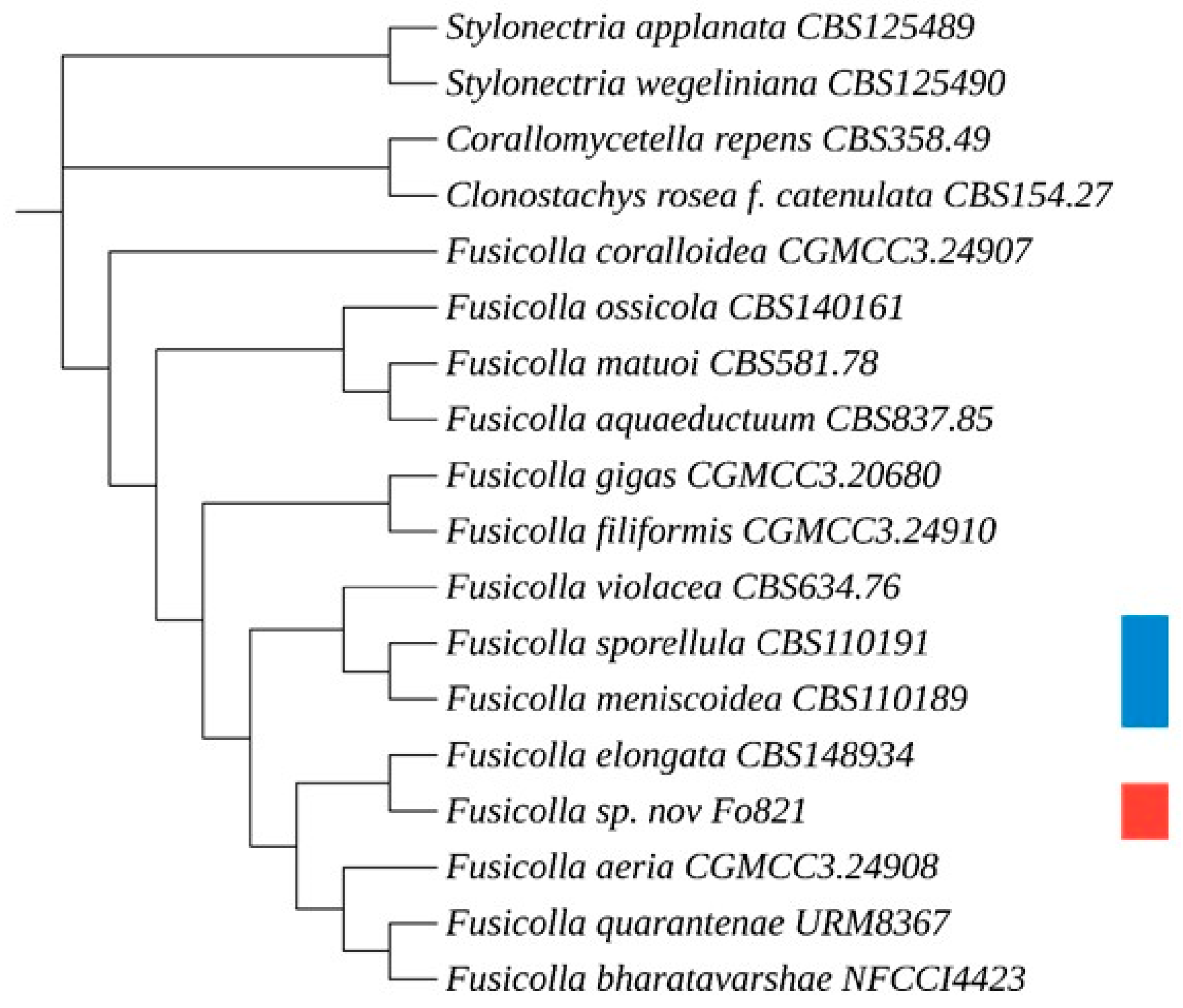

3.7. Phylogenetic Analyses

We constructed phylogenetic trees using MEGA 11 software to analyse the placement of

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. within the genus

Fusicolla. The first phylogenetic tree (

Figure 3) was constructed using a multilocus analysis based on the concatenated sequences of the ITS, Btub2, D1/D2 and RPB2 genetic regions. This analysis showed that the new fungal isolate,

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov., clustered distinctly away from all other species of this genus, indicating its unique genetic identity. Four additional trees were then constructed (

Figure 4), each based on a single genetic region (ITS, Btub2, D1/D2 and RPB2). The results of the ITS, RPB2 and Btub2 trees indicate that

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. is a distinct lineage within the genus, separate from other recognised species. The single-locus D1/D2 tree also supports the distinctness of

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov., albeit with a lower degree of separation from a closely related species.

The phylogenetic analysis provides compelling evidence that Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. should be classified as a new species within the genus Fusicolla. Furthermore, the consistent separation of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. in single-locus trees provides additional evidence for its unique taxonomic status. The results of this analysis provide substantial evidence to support the classification of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. as a distinct species within the genus Fusicolla.

3.8. Taxonomy

Fusicolla massiliensis Elias C. & Ranque S. sp. nov.

Etymology: Named in honour of Marseille, France, the city where the species was first isolated.

Diagnosis: This species is distinctly different from the other three Fusicolla species examined in this work. Although it has flat and moist colonies similar to those of F. sporellula, its appearance differs from that of F. meniscoidea, which has a slightly gelatinous or sticky consistency with subtle aerial mycelial growth, and from F. acetilerea, which has a slightly slimy or mucilaginous texture, accompanied by a prominent aerial mycelium.

Type: France: Marseille. Soil (PAH-polluted soil sample SS6), 20 May 2022. (Holotype IHEM 29111 / Fo821, stored in a metabolically inactive state). GenBank: PP851726 (ITS), PP892465 (B-tub2), PP869636 (TEF-1a).

Description: Macroscopically, colonies of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. are characterised by rapid growth within four to five days on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar gentamicin chloramphenicol (SDA GC) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) media at an optimum temperature of 25o C. No growth was observed for this new species at 4, 37 and 56o C. Colonies exhibit a distinct chrome-yellow to orange colour both on the surface and reverse after four to five days of incubation. In older colonies, the colour of the Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. changes to a pale brownish shades after 3 weeks of incubation. Colonies are flat and moist, and have a smooth, glabrous, slimy and slightly hairy morphology. Aerial mycelial growth is absent or weak. Microscopic examination of the new Fusicolla species shows filiform, smooth-walled and septate hyaline hyphae. Conidiophores emerged directly from sparsely branched somatic hyphae, rarely bearing terminal and lateral phialidic conidiogenous cells. Microconidia tended to aggregate, whereas macroconidia were rarely seen. Both microconidial and macroconidial structures were observed exclusively in colonies grown on PDA.

The BiologTM carbon source assimilation profile revealed a distinct metabolic cartography for this species. Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov metabolized and assimilated several carbon substrates, succinic acid mono-methyl ester, p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, bromosuccinic acid, sebacic acid, N-acetyl-D-galactosamine, D-galacturonic acid, α-cyclodextrin, D-melibiose and N-acetyl-glutamic acid, more extensively and more readily than all three reference species F. meniscoida, F. acetilerea, and F. sporellula. These differences in metabolic profiles suggest a distinct preference or efficiency of this new species for these nutrient substrates, highlighting potential differences in metabolic pathways or affinity for particular substrates between these different species.

Host: Soil

Additional specimen examined: Fusicolla sporellula: Reference: Country of origin: South Africa. Substrate details: Soil. (CBS 110191) GenBank: MW827614.1 (ITS), MW834308.1 (B-tub2), MW834012.1 (RPB2), MW827655.1 (D1/D2).

Additional specimen examined: Fusicolla meniscoidea: Reference: Australia. Substrate details: Soil (CBS 110189) GenBank: MW827613.1 (ITS), MW834306.1 (B-tub2), MW834010.1 (RPB2), MW827654.1 (D1/D2).

Additional specimen examined: Fusicolla acetilerea: Reference: Country of origin Japan. Substrate details: Soil (CBS 123378) GenBank: HQ897790.1 (ITS), - (B-tub2), HQ897701.1 (RPB2), U88108.1 (D1/D2).

4. Discussion

The genus

Fusicolla comprises species that are primarily saprotrophic, obtaining nutrients by decomposing dead organic matter, and are therefore found on a wide range of substrates, including soil [

8]. In a related study aimed at revealing fungal community structure and diversity in soil samples with varying levels of PAH contamination, we used an innovative approach known as culturomics, originally applied to the study of the human gut microbiome [

14], combined for the first time with ITS metabarcoding in soil microbial ecology studies.

One of the five culture media employed in this culturomics approach, the FastFung medium [

15], yielded a fungal strain that, upon identification with MALDI-TOF MS, yielded log scores below 1.70. This prompted a subsequent molecular analysis targeting five key genetic markers. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS1/ITS2) regions of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU), a fragment of the β-tubulin gene (B-tub2), a fragment of the translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene (TEF-1-alpha), a fragment of the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), and the D1/D2 domains of the large subunit ribosomal DNA (LSU) were analysed. The multilocus phylogenetic tree (

Figure 3) constructed using concatenated sequences of ITS, Btub2, RPB2, and D1/D2, showed that

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. forms a distinct clade separate from other known

Fusicolla species such as

Fusicolla meniscoidea and

Fusicolla elongata. In the single-locus phylogenetic trees for ITS, RPB2 and Btub2, the novel

Fusicolla species was observed to cluster uniquely, thus indicating divergence from other closely related species such as

F.

aeria,

F. bharatavarshae, or

F. sporellula. In the D1/D2 single-locus tree, although with a lesser degree of separation,

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. was consistently placed in distinct clades, indicating a significant genetic divergence from other members of this genus, thereby reinforcing its classification as a novel species within the genus

Fusicolla. These results suggest that the newly isolated

Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. represents a novel species, as it consistently shows across multiple phylogenetic analyses, significant divergence from the other known and described taxa within the genus

Fusicolla across multiple phylogenetic analyses.

In 2023, Zeng & Zhuang [

9] identified

Fusicolla aeria, a new Fusicolla species, which they described as being closely related to

F. acetilerea and F. elongata. Our work corroborates these findings, as both single-locus and multi-locus phylogenetic trees suggest a genetic affinity between our newly described

Fusicolla species, and

F. aeria, as well as the other two

Fusicolla species,

F. acetilerea and F. elongata. However, morphological comparisons reveal distinct differences; unlike

F. aeria,

F. acetilerea and F. elongata, which exhibit abundant aerial mycelial growth, a characteristic that was also observed in our study for

F. acetilerea, our isolate

F. massiliensis sp. nov. lacks this characteristic and also shows differences in colony morphology, with a distinct shade of chrome yellow to orange appearance. These observations are consistent with the findings of Zeng & Zhuang [

9], who highlighted significant morphological and genetic differences between

F. aeria,

F. acetilerea and F. elongata. Similarly, our study shows clear differences between

F. massiliensis sp. nov.,

F. acetilerea, and the other two species when compared to their study.

Compared to other studies reporting the isolation and characterisation of novel

Fusicolla species, this work incorporated scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to more thoroughly examine microscopic structures [

3,

9]. In contrast to light microscopy, the use of the novel tabletop SEM allowed for high-resolution, detailed morphological assessment of fungal microstructures after quick and simple sample preparation, as opposed to complex and laborious traditional protocols. The integration of SEM observation for the characterisation of novel fungal species could therefore be a valuable tool to accurately discriminate morphological structures and gain deeper insight into significant morphological features. In this study, the use of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allowed to obtain, for the first time, an ultrastructural characterisation of this new fungal species with unprecedented precision. Unlike light microscopy, which is limited in resolution and magnification capacity, SEM offered the possibility of achieving higher magnifications while maintaining exceptional image quality. This ability to observe microscopic details with such finesse allowed more precise and higher quality images to be obtained, representing an important methodological advance in the description of species of the genus

Fusicolla. These results highlight the interest of systematically integrating SEM into taxonomic studies to reveal morphological details that are difficult to access using other techniques.

Antifungal susceptibility testing has shown low MICs for amphotericin B, whereas high MICs have been observed for azole compounds. As this species belongs to an environmental genus that has not been implicated in human or veterinary disease [

16], antifungal susceptibility testing data are not yet available for the previously described species within the genus

Fusicolla. Nevertheless, these analyses were performed to document the antifungal susceptibility profile of this novel species in an effort to provide a valuable baseline should members of this genus be identified as human pathogens in the future.

We observed a relatively rapid colony growth phenotype for this

Fusicolla isolate, which contrasts with the findings of Zeng & Zhuang [

9], who reported a slower growth rate for their three newly described species

F. aeria, F. filiformis, and

F. coralloidea. The slow-growing phenotype is considered to be a common trait among cosmospora-like fungi [

3]. However, this phenotype was reported by Lechat & Rossman for

F. ossicola and another closely related

Fusicolla species,

F. melogrammae which exhibited an unusual fast-growing phenotype [

3]. In this study, Lechat & Rossman described

F. ossicola colonies as slimy, with cream to pale orange centres, white margins, and rare aerial hyphae which bears to some extent some resemblance to the morphology observed in our species. The primary colour of the colonies remained stable, ranging from yellowish/ creamy orange to pale brownish orange hues, which shifted further towards a brown/ dark pigmentation after one month of incubation. This dark pigmentation is noteworthy as it is a common feature of dematiaceous fungi, where melanin production in the conidial and hyphal cell walls results in this dark aspect. While our newly isolated species showed this melanin-associated pigmentation, the three reference species

F. sporellula,

F. acetilerea, and

F. meniscoidea did not show this dematiaceous feature, typical of melanin-rich fungal species.

While morphological characterisation provided an initial differentiation between these Fusicolla species, phylogenetic analysis alongside physiological analysis provided a more definitive distinction between the four species and therefore a more comprehensive description of the newly isolated species. The Biolog™ phenotypic analysis revealed distinct carbon source assimilation/oxidation profiles and metabolic mapping that distinguished F. massiliensis sp. nov. from the three selected reference species within the genus. In fact, the results of the Biolog™ system analysis were particularly relevant, showing that the physiological profile of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov., and consequently its metabolic pathways and affinity for specific metabolic substrates, differed significantly from those of the three reference species, F. sporellula, F. acetilerea and F. meniscoidea.

In conclusion, the environmental fungal isolate Fo821 is identified and described as Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov., a novel species that can be easily distinguished from other species within the genus Fusicolla due to its unique genomic sequences as well as distinct morphological, chemical and physiological profiles. Comprehensive studies in different ecosystems and substrates, in previously unexplored regions or matrices, will be crucial to further enhance our knowledge and unravel the species diversity within the genus Fusicolla.

Figure 1.

Growth of cultures on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar + gentamicin and chloramphenicol (SDAGC) after five days of incubation at 25° C. The colour of both the recto and verso colonies of the reference strains was white/beige to pale buff, whereas that of the novel species was yellowish to orange. (A) Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov.; (B) Fusicolla acetilerea CBS 123378; (C) Fusicolla meniscoidea CBS 110189; and (D) Fusicolla sporellula CBS 110191.

Figure 1.

Growth of cultures on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar + gentamicin and chloramphenicol (SDAGC) after five days of incubation at 25° C. The colour of both the recto and verso colonies of the reference strains was white/beige to pale buff, whereas that of the novel species was yellowish to orange. (A) Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov.; (B) Fusicolla acetilerea CBS 123378; (C) Fusicolla meniscoidea CBS 110189; and (D) Fusicolla sporellula CBS 110191.

Figure 2.

Microscopic morphology of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. (A-C) Thread-like hyphae with branched conidiophores observed by light microscopy (A, B, magnification x1000, C, magnification x400). (D-F) Thread-like hyaline hyphae with conidiophores arising directly from them as observed by scanning electron microscopy (hyphae (blue arrow), conidiophores (orange arrow)). (G) Macroconidial structure. (H, I, J, L) Conidiophores with microconidia (hyphae (blue arrow), conidiophores (orange arrow), microconidia (yellow arrow)). (K) Microconidia. SEM acquisition settings appear on each micrograph as follows: Instrument, accelerating voltage, working distance, magnification, detector and scale.

Figure 2.

Microscopic morphology of Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. (A-C) Thread-like hyphae with branched conidiophores observed by light microscopy (A, B, magnification x1000, C, magnification x400). (D-F) Thread-like hyaline hyphae with conidiophores arising directly from them as observed by scanning electron microscopy (hyphae (blue arrow), conidiophores (orange arrow)). (G) Macroconidial structure. (H, I, J, L) Conidiophores with microconidia (hyphae (blue arrow), conidiophores (orange arrow), microconidia (yellow arrow)). (K) Microconidia. SEM acquisition settings appear on each micrograph as follows: Instrument, accelerating voltage, working distance, magnification, detector and scale.

Figure 3.

Multilocus phylogenetic tree presenting the novel isolated species Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. and 17 reference strains, based on concatenated ITS, D1D2, B-tub2, and RPB2 sequences. Clonostachys rosea f. catenulata CBS 154.27, Corallomycetella repens CBS 359.49, Stylonectria wegeliniana CBS 125490, and Stylonectria applanata CBS 125489 were used as outgroups. The multilocus phylogenetic tree was generated with the maximum parsimony method using MEGA 11 software, and a bootstrap value of 1000 replications, and visualized with iTOL v6. The red square indicates the novel fungal species under description, while blue squares represent additional specimens examined, including established type strains obtained from the CBS collection for genotypic and phenotypic comparison.

Figure 3.

Multilocus phylogenetic tree presenting the novel isolated species Fusicolla massiliensis sp. nov. and 17 reference strains, based on concatenated ITS, D1D2, B-tub2, and RPB2 sequences. Clonostachys rosea f. catenulata CBS 154.27, Corallomycetella repens CBS 359.49, Stylonectria wegeliniana CBS 125490, and Stylonectria applanata CBS 125489 were used as outgroups. The multilocus phylogenetic tree was generated with the maximum parsimony method using MEGA 11 software, and a bootstrap value of 1000 replications, and visualized with iTOL v6. The red square indicates the novel fungal species under description, while blue squares represent additional specimens examined, including established type strains obtained from the CBS collection for genotypic and phenotypic comparison.

Figure 4.

Four single-locus phylogenetic trees using the genomic regions (A) ITS, (B) D1D2, (C) β-tub2, and (D) RPB2. Incomplete sequence data for all loci limited the inclusion of all species in the trees. Clonostachys rosea f. catenulata CBS 154.27, Corallomycetella repens CBS 359.49, Stylonectria wegeliniana CBS 125490, and Stylonectria applanata CBS 125489 were used as outgroups. The multilocus phylogenetic tree was generated by the maximum parsimony method using MEGA 11 software, with a bootstrap value of 1000 replicates, and visualized with iTOL v6. The red square indicates the novel fungal species under description, while blue squares represent additional specimens examined, including established type strains obtained from the CBS collection for genotypic and phenotypic comparison.

Figure 4.

Four single-locus phylogenetic trees using the genomic regions (A) ITS, (B) D1D2, (C) β-tub2, and (D) RPB2. Incomplete sequence data for all loci limited the inclusion of all species in the trees. Clonostachys rosea f. catenulata CBS 154.27, Corallomycetella repens CBS 359.49, Stylonectria wegeliniana CBS 125490, and Stylonectria applanata CBS 125489 were used as outgroups. The multilocus phylogenetic tree was generated by the maximum parsimony method using MEGA 11 software, with a bootstrap value of 1000 replicates, and visualized with iTOL v6. The red square indicates the novel fungal species under description, while blue squares represent additional specimens examined, including established type strains obtained from the CBS collection for genotypic and phenotypic comparison.

Table 1.

Primer sets used to amplify the ITS, B-tub2, TEF1, D1/D2 and RPB2 genetic regions.

Table 1.

Primer sets used to amplify the ITS, B-tub2, TEF1, D1/D2 and RPB2 genetic regions.

| Primers |

Sequences |

Targeted Regions |

References |

| ITS1 |

TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG |

18S-5.8S |

[17] |

| ITS2 |

GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC |

18S-5.8S |

[17] |

| ITS3 |

GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC |

5.8S-28S |

[17] |

| ITS4 |

TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

5.8S-28S |

[17] |

| ITS1 |

TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG |

18S-5.8S, 5.8S-28S |

[17] |

| ITS4 |

TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

18S-5.8S, 5.8S-28S |

[17] |

| Bt-2a |

CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG |

B-tub2 |

[18] |

| Bt-2b |

TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC |

B-tub2 |

[18] |

| EF1-728F |

GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC |

TEF1 |

[19] |

| EF1-986R |

ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC |

TEF1 |

[19] |

| D1 |

AACTTAAGCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGA |

28S |

[20] |

| D2 |

GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG |

28S |

[20] |

| fRPB2-5F |

GAYGAYMGWGATCAYTTYGG |

RNA polymerase II gene |

[2] |

| fRPB2-7cr |

CCCATRGCTTGTYYRCCCAT |

RNA polymerase II gene |

[2] |

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of the reference strains that were used for the phylogenetic analyses.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of the reference strains that were used for the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species |

Herbarium/Strain Numbers |

Genbank Accession Numbers |

| ITS |

LSU |

Btub2 |

RPB2 |

| F. acetilerea |

BBA:63789T

|

HQ897790.1 |

U88108.1 |

- |

HQ897701.1 |

| F. aeria |

CGMCC:3.24908T

|

OQ128334.1 |

OQ128338.1 |

OQ134100.1 |

OQ134111.1 |

| F. aquaeductuum |

CBS:837.85T

|

NR_173406.1 |

NG_076686.1 |

KM232094.1 |

HQ897744.1 |

| F. betae |

BBA:64317T

|

OW983080.1*

|

- |

- |

HQ897781.1 |

| F. bharatavarshae |

NFCCI:4423T

|

MK152510.1 |

MK152511.1 |

MK376462.1 |

MK157022.1 |

| F. cassiae-fistulae |

MFLUCC:19-0318T

|

NR_171299.1 |

NG_073862.1 |

- |

- |

| F. coralloidea |

CGMCC:3.24907T

|

OQ128333.1 |

OQ128337.1 |

OQ134099.1 |

OQ134110.1 |

| F. elongata |

CBS:148934T

|

ON763203.1 |

ON763200.1 |

ON745628.1 |

ON759297.1 |

| F. epistroma |

BBA:62201T

|

OP179099.1*

|

AF228352.1 |

- |

HQ897765.1 |

| F. filiformis |

CGMCC:3.24910T

|

OQ128332.1 |

OQ128336.1 |

OQ134098.1 |

OQ134109.1 |

| F. gigantispora |

MFLU:16-1206T

|

MN047104.1 |

MN017869.1 |

- |

- |

| F. gigas |

CGMCC:3.20680T

|

OK465362.1 |

OK465449.1 |

OQ134102.1*

|

OQ134113.1*

|

| F. guangxiensis |

CGMCC:3.20679T

|

OK465363.1 |

OK465450.1 |

- |

OQ134114.1 |

| F. hughesii |

NFCCI:4234T

|

MG779450.1 |

MG779452.1 |

- |

- |

| F. matuoi |

CBS:581.78T

|

KM231822.1 |

KM231698.1 |

KM232093.1 |

HQ897720.1 |

| F. melogrammae |

CBS:141092T

|

NR_155096.1 |

NG_058275.1 |

MW834305.1 |

- |

| F. meniscoidea |

CBS:110189T

|

MW827613.1 |

MW827654.1 |

MW834306.1 |

MW834010.1 |

| F. merismoides |

CBS:186.34T

|

MH855482.1 |

MH866963.1 |

- |

- |

| F. ossicola |

CBS:140161T

|

NR_161034.1 |

MF628021.1 |

MW834307.1 |

MW834011.1 |

| F. quarantenae |

URM:8367T

|

MW553789.1 |

MW553788.1 |

MW556624.1 |

MW556626.1 |

| F. reyesiana |

PAD:S00015T

|

MT554915.1MT554892.1 |

- |

- |

- |

| F. septimanifiniscientiae |

CBS:144935T

|

MK069422.1 |

MK069418.1 |

MK069408.1 |

- |

| F. siamensis |

MFLUCC:17-2577T

|

NR_171300.1 |

NG_073863.1 |

- |

- |

| F. sporellula |

CBS:110191T

|

MW827614.1 |

MW827655.1 |

MW834308.1 |

MW834012.1 |

| F. violacea |

CBS:634.76T

|

KM231824.1 |

KM231700.1 |

KM232095.1 |

HQ897696.1 |

| Corallomycetella repens |

CBS:358.49T

|

MH856551.1 |

KM231708.1 |

KC479784.1 |

KM232391.1 |

| Stylonectria applanata |

CBS:125489T

|

HQ897805.1 |

KM231689.1 |

KM232083.1 |

HQ897739.1 |

| Stylonectria wegeliniana |

CBS:125490T

|

KM231817.1 |

KM231690.1 |

KM232084.1 |

KM232240.1 |

| Clonostachys rosea |

CBS:154.27T

|

MH854911.1 |

MH866405.1 |

AF358160.1 |

OQ927866.1 |

Table 3.

Results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility tests.

Table 3.

Results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility tests.

| MIC * (mg/L) Read at 48 h |

|---|

| |

AMB |

ITC |

POS |

VOR |

IVU ** |

|

Fusicolla sp. nov. Fo821 |

0.94 |

> 32 |

> 32 |

> 32 |

> 32 |

| |

S |

R |

R |

R |

R |