1. Introduction

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon’s North West Region, which has persisted since 2016, represents not only a socio-political conflict but also a site of profound economic resistance. In this volatile context, economic disobedience has emerged as a deliberate and transformative strategy deployed by marginalized populations to challenge the central state’s authority. Characterized by organized boycotts and the proliferation of informal trade networks, these actions transcend mere survival mechanisms, asserting collective autonomy and reimagining economic sovereignty. This study situates these dynamics within the theoretical frameworks of Scott’s Weapons of the Weak (1985) and Bayart’s Politics of the Belly (1993), emphasizing their relevance to contemporary resistance economies in postcolonial settings.

This research significantly advances existing knowledge by filling critical gaps in the literature on economic resistance. While prior studies, such as those by Talla (2024) and Musah (2022), have explored the socio-political dimensions of the Anglophone Crisis, insufficient attention has been paid to how economic agency becomes a tool of defiance in such contexts. By interrogating grassroots economic disobedience, this paper sheds new light on the interplay between economic sovereignty and governance in politically contested regions.

Moreover, the findings hold important policy implications. The strategies examined ranging from boycotts of state-affiliated enterprises to cross-border trade with Nigeria demonstrate how informal economies can both undermine state control and provide alternative pathways for economic resilience. These insights can inform governance reforms and conflict resolution strategies, particularly in regions where state authority is fragile or contested.

Finally, this study positions the Anglophone Crisis within a global discourse on resistance economies. By drawing comparisons to other conflict-prone regions where economic disobedience has similarly destabilized centralized governance, it accentuates the universality of grassroots economic resistance in the face of state marginalization. The fieldwork, conducted in Bamenda, Kumbo, and Ndop, integrates qualitative interviews and economic data to provide a comprehensive and globally relevant analysis of how local actors reconfigure power dynamics through economic autonomy. This study thus seeks to address the following questions:

How have boycotts and informal trade networks reshaped economic and political power in the North West Region?

In what ways do these strategies destabilize formal economic governance?

What implications do these practices hold for reimagining economic sovereignty in postcolonial and global contexts?

By exploring these questions, the paper not only advances theoretical discourses on resistance economies but also contributes practical insights for policymakers grappling with governance challenges in conflict-affected regions.

2. Literature Review

Economic disobedience and alternative economies, though often understated in the literature on political resistance, serve as critical mechanisms of contestation against state authority, particularly in politically and economically marginalized regions. This review interrogates the role of boycotts and informal trade networks in the North West Region of Cameroon, providing an analytical framework to explore these strategies as forms of resistance. By integrating Bayart’s (2009) politics of the belly, Scott’s (1985) weapons of the weak, and Murrey’s (2024) slow dissent, the review positions economic disobedience as a multidimensional resistance strategy within the broader framework of the Anglophone crisis, examining intersections between political, cultural, and economic dimensions.

Bayart’s (2009) Politics of the Belly provides a critical lens for understanding state authority in postcolonial Africa. Bayart emphasizes how the state’s extractive and patronage-driven economic systems perpetuate inequality and marginalization. In the North West Region of Cameroon, economic disobedience manifesting through boycotts and informal trade networks directly challenges these patronage networks. Boycotts of education, trade, and governance reflect symbolic refusals to participate in an exploitative economic system. For example, the 2016 Anglophone Teachers’ Strike led to the widespread boycott of schools in protest against government-imposed Francophone curricula, destabilizing the state’s education system and drawing attention to systemic inequality. Such acts destabilize the state’s ability to control resources, demonstrating the resistance of marginalized communities to the monopolization of wealth by political elites.

Scott’s (1985) weapons of the weak complements Bayart’s analysis by examining how everyday resistance occurs through subtle, decentralized actions. In Cameroon’s North West Region, informal trade networks epitomize these “weapons,” as communities circumvent state-imposed tariffs and taxation. These networks, which rely heavily on cross-border trade with Nigeria, create alternative economic spaces that resist state authority while addressing the community’s survival needs. For example, in 2018, traders in Bamenda, the regional capital, expanded informal cross-border commerce after the government implemented punitive taxes on local businesses. Scott’s framework highlights how informal economies serve as both survival strategies and political statements, particularly in regions experiencing protracted conflict.

Murrey’s (2024) concept of slow dissent introduces a vital, contemporary dimension to this discourse. Murrey argues that resistance is not always immediate or overt but can take the form of long-term, gradual processes that reimagine societal relations and structures. In the context of Cameroon, the economic disobedience seen through boycotts and informal trade networks can be interpreted as a form of slow dissent, challenging not only state authority but also global imperialist structures that influence local governance and economies. For instance, informal trade networks in the region have resisted the influence of French-dominated global trade systems, creating autonomous economic spaces that empower local communities. This perspective broadens the analytical scope, situating Cameroon’s resistance strategies within a larger critique of imperial relations.

The ongoing Anglophone crisis has generated substantial discourse on political identity, governance, and legitimacy. However, the economic mechanisms through which marginalized communities contest state authority remain underexplored. Eyoh’s (1998) foundational work highlights the deep-rooted marginalization of Anglophone communities, linking boycotts to broader narratives of political disenfranchisement. Yet, his analysis does not fully explore how these economic strategies operate as sustained forms of resistance.

Peace’s (2020) work on online and offline activism connects political boycotts to broader resistance movements but overlooks the role of informal trade networks as economic alternatives. A more comprehensive analysis of these networks would illuminate how they not only provide economic autonomy but also challenge state-controlled markets, offering communities avenues for survival and resistance.

The relationship between boycotts and informal trade networks remains insufficiently theorized in existing literature. Ketzmerick (2023) situates informal trade networks within the global struggle for autonomy, noting their role in insurgent movements. However, the specific interplay between these networks and local boycotts in Cameroon’s North West Region requires deeper analysis. How do these strategies mutually reinforce each other to destabilize state authority?

Willis, Angove, and Mbinkar (2020) highlight the socio-economic dimensions of resistance, focusing on personal testimonies from those affected by the Anglophone crisis. While their work emphasizes the continuity of economic exploitation, it stops short of exploring the long-term impacts of economic disobedience on community livelihoods. Musah (2022) addresses this gap partially, examining how government actions exacerbate the crisis and radicalize resistance. However, neither fully addresses how economic strategies sustain resistance over time while reshaping local economies.

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, this review proposes a conceptual framework that highlights the interconnectedness of boycotts, informal trade networks, and slow dissent. Boycotts represent overt refusals to engage with state-controlled systems, signaling a collective rejection of state authority. Informal trade networks, operating outside formal state structures, provide essential goods and services while creating spaces for economic autonomy. Together, these strategies form a dual-pronged approach to resistance that challenges state legitimacy while fostering local resilience.

Murrey’s (2024) framework of slow dissent further enriches this analysis by positioning these acts of resistance within a broader, global critique of imperial relations. The gradual reimagining of economic and political systems in Cameroon’s North West Region exemplifies how local resistance strategies can contribute to larger processes of worldmaking.

3. Methodology

This study employed a qualitative exploratory design to examine how economic disobedience and alternative economies are disrupting state authority in Cameroon’s North West Region. Participants included purposively sampled key stakeholders: 25–30 semi-structured interviews with local traders (15), community leaders (5), activists (5), and government officials (5), ensuring diverse socioeconomic and political perspectives. Eight focus group discussions (FGDs), stratified by age and occupation, engaged 6–8 participants each to capture collective narratives of resistance.

Participant observation was conducted over three months in markets, community assemblies, and key protest sites (Bamenda, Kumbo, and Ndop) to document informal trade practices and grassroots mobilizations. Primary data from interviews, FGDs, and field notes were triangulated with document analysis of government policies, NGO reports, and media archives to contextualize resistance strategies within historical and institutional frameworks.

Ethical protocols prioritized informed consent, and cultural sensitivity, particularly given the region’s political volatility. Potential limitations, including restricted access due to insecurity and sampling bias, were mitigated through snowball sampling to include marginalized voices and iterative cross-verification of data sources. The study rigorously captured the complexity of economic resistance, balancing micro-level agency with macro-level governance challenges. This approach not only enhanced empirical validity but also illuminated how informal economies reconfigured power in conflict zones, offering transferable insights for contested regions globally.

4. Findings

4.1. Economic Disobedience and Alternative Economies in the Anglophone Crisis

This study examines the dynamics of economic disobedience and the rise of alternative economies as forms of resistance in Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis in the Northwest Region. Building on theoretical frameworks like Bayart’s “politics of the belly” and Scott’s “weapons of the weak,” the analysis explores how economic boycotts, informal trade networks, and cultural resistance serve as mechanisms to contest state authority. These forms of resistance, while integral to reclaiming autonomy, also reveal complex socio-economic, political, and cultural dynamics. This section delves into diverse Anglophone experiences, the varying responses, and the role of gender in resistance strategies, and offers comparative insights from other conflict contexts, enhancing the depth of the analysis.

4.2. Economic Boycotts as Resistance Strategies

Economic boycotts, particularly the “ghost town” strikes, have been central to the resistance economy of the Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon. These boycotts, in which businesses and public services shut down on designated days, serve as a mechanism to challenge state authority, disrupt revenue flows, and assert a distinct Anglophone political identity. However, the efficacy of these boycotts is contingent on local socio-economic conditions, enforcement mechanisms, and the broader political economy of resistance. By examining economic boycotts through the lens of defiant scholarship and resistance economics, this section evaluates how these strategies reflect both deliberate acts of defiance and pragmatic adaptations within a volatile conflict economy.

The theoretical framework of defiant scholarship provides a lens to analyze how economic resistance operates beyond conventional political movements. As Mbembe (2001) argues, resistance in postcolonial Africa is often shaped by fluid, decentralized, and adaptive strategies that emerge from local realities rather than being dictated by elite political actors. The ghost town strikes illustrate this dynamic, as they are both a tool of defiance against state control and a survival strategy necessitated by fear and coercion. Understanding this duality is key to assessing their effectiveness in the ongoing crisis.

4.2.1. Urban Enforcement and Political Symbolism: The Case of Bamenda

In urban centers like Bamenda, ghost town boycotts have gained widespread adherence due to a combination of political solidarity, coercion, and community surveillance. The presence of militant enforcers, Ambazonian Defence Force (ADF) ensures compliance, transforming the boycotts into a symbolic battleground between state authority and local resistance networks. The enforcement mechanisms of ghost towns are not merely spontaneous acts of protest but are institutionally reinforced by separatist groups that view economic non-cooperation as a fundamental pillar of the struggle.

During field interviews, local traders emphasized the socio-political pressures surrounding boycott participation. Mrs. Ndang, a shop owner in Mankon, noted:

“If you don’t respect ghost towns, people will accuse you of betraying the struggle.” This fear is compounded by the presence of Ambazonian armed groups that patrol the streets, reinforcing participation through intimidation. Similarly, Mr. Mbah, a high school teacher, explained, “The ‘boys’ monitor the streets, ensuring that no one opens their business on ghost town days every Monday.”

The function of these enforced shutdowns aligns with Bayart’s (1993) theory of the ‘politics of the belly,’ which highlights how economic practices in postcolonial states are deeply intertwined with political resistance and state patronage. Ghost town boycotts can be viewed as a direct countermeasure to state-driven economic marginalization, wherein local populations disrupt economic activity to expose the vulnerabilities of a centralized economic order that largely ignores their grievances.

However, the paradox of prolonged economic disruptions where resistance simultaneously reinforces identity while deepening economic precarity raises questions about the long-term sustainability of boycotts as a tool for political change. Business owners express concerns about their financial viability, as prolonged closures lead to liquidity crises, stock depletion, and reduced access to supply chains. Mr. Augustin Nwa, a merchant in Bamenda’s commercial district, lamented:

“It’s difficult to plan; even if I want to sell, the roads are closed, and my customers are scared to come out.”

This demonstrates the unintended consequences of economic resistance, where the very strategy employed to challenge state control also exacerbates financial hardships for those engaged in the struggle.

4.2.2. Rural Pragmatism and Subtle Defiance

In contrast to urban centers, rural communities such as Nwa, Fungom, and Widikum demonstrate lower adherence to economic boycotts due to pressing survival needs. In these areas, economic resistance takes on a pragmatic and adaptive form rather than an absolute shutdown of activities. While urban populations can afford sporadic economic inactivity due to larger financial buffers, rural economies are driven by daily subsistence activities, making strict adherence to boycotts infeasible. Mr. Fon, a farmer from Widikum, emphasized,

“We need to sell what we harvest to feed our families. We can’t stop just because of ghost towns.”

Rather than outright defiance, rural populations engage in covert economic activities altering market hours, relocating trade to hidden spaces, and leveraging informal networks to sustain their livelihoods. This adaptation reflects what Murrey (2024) refers to as “slow dissent”, wherein marginalized communities engage in everyday resistance that is less overt but equally significant in challenging systemic oppression.

The contrast between urban enforcement and rural pragmatism stresses a fundamental limitation of economic boycotts: while effective in cities, their applicability in rural economies where daily trade is essential for subsistence is constrained. Rural populations must navigate a delicate balance between symbolic resistance and economic survival, a reality that challenges the efficacy of blanket economic shutdowns.

Furthermore, tensions exist between urban-based activists and rural traders, with the latter often feeling that their struggles are overlooked in the broader resistance discourse.

“In the cities, they can afford to close their shops for a day, but we cannot. We are already suffering from the conflict, and stopping our work would make life harder,”

noted a trader in Nwa. This critique aligns with defiant scholarship’s emphasis on recognizing the diverse expressions of resistance rather than imposing a singular strategy.

4.2.3. Economic Consequences of Prolonged Boycotts: Resistance or Self-Sabotage?

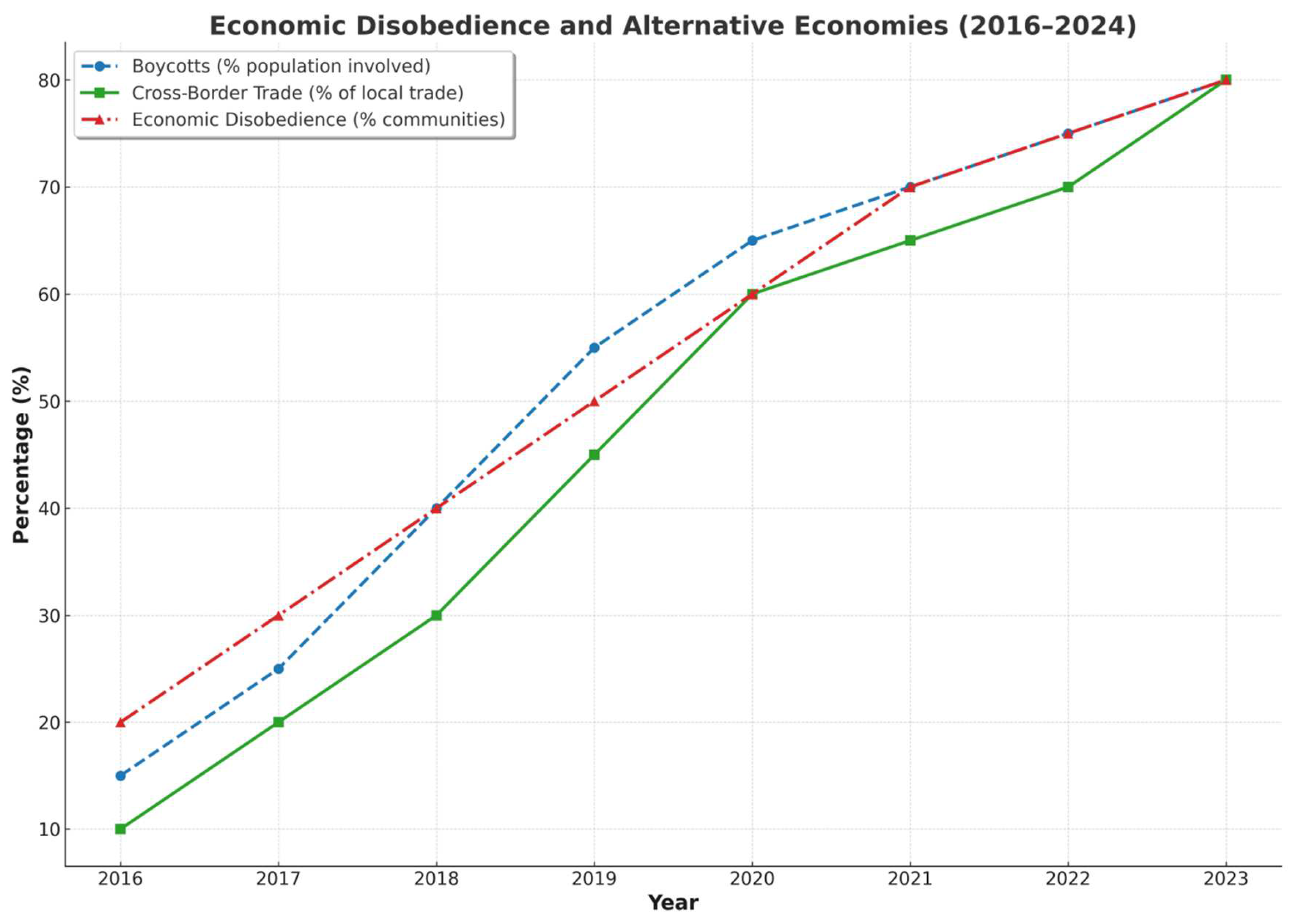

While ghost town strikes effectively signal dissent, their long-term economic repercussions are severe. Quantitative data from Talla (2024) indicates that 78% of urban traders in Bamenda comply with the strikes, whereas rural participation remains around 55%. The economic strain is particularly acute for small-scale traders, who face dwindling incomes and supply chain disruptions.

Moreover, cross-border trade with Nigeria has surged from 10% to 80% (Talla, 2024) as traders seek alternatives to sustain livelihoods. While this shift reflects economic adaptation, it also signals the diminishing influence of local boycott strategies. As reliance on Nigerian markets grows, the potential dilution of economic resistance poses challenges for the Anglophone movement, requiring a reassessment of economic disobedience as a long-term strategy.

Additionally, the state has adapted to these disruptions by redirecting economic flows. The government has increased investments in alternative trade routes and encouraged economic shifts toward more compliant Francophone regions, weakening the leverage of the boycotts. This reinforces the state’s resilience in countering economic resistance and suggests that unilateral economic shutdowns may no longer serve as the most effective tool for the movement.

The divergent experiences of economic boycotts in Cameroon’s North West region reflect broader tensions in conflict economies: the balance between economic survival and political defiance. While urban populations utilize ghost towns as visible acts of resistance, rural populations engage in more flexible forms of defiance, adapting their economic behaviors to navigate both conflict and survival imperatives.

As cross-border trade and informal networks continue to evolve, the future of Anglophone resistance may lie not in absolute economic shutdowns but in economic reconfiguration creating alternative markets that sustain both the struggle and the livelihoods of those engaged in it.

Moving forward, the Anglophone movement must reconcile economic resilience with political defiance, ensuring that resistance strategies do not inadvertently undermine the very communities they seek to empower. By embracing the lessons of defiant scholarship and recognizing the evolving economic landscape, a more sustainable and adaptive resistance economy can emerge.

Figure 1 illustrates the Northwest Region’s socio-economic rupture amid Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis. Boycotts (80% by 2023) align with Konings’ (2011) analysis of civil society resistance to Yaounde’s exclusionary governance, reflecting the rejection of Francophone-dominated policies. Cross-border trade’s surge (10%–80%) mirrors Konings’ (2011) study of informal economies as survival tactics, as conflict disrupts local markets, forcing reliance on Nigeria for food and currency. Economic disobedience, per Nyamnjoh (1999), signifies grassroots defiance against centralized authority, with Anglophone communities evading taxes and adopting parallel currencies, rejecting a state deemed illegitimate. This reflects a systemic shift from formal compliance to survival-based autonomy, rooted in decades of political-economic marginalization.

The convergence of these trends in the North West Region of Cameroon reflects a broader response to governance failures, entrenched economic marginalization, and political instability. The proliferation of decentralized alternatives ranging from informal trade networks to community-driven financial systems demonstrates resilience and local innovation but also signals deep-seated distrust in state institutions. These shifts, while adaptive, undermine formal economic structures, reducing state revenue and weakening regulatory oversight in a region already grappling with conflict and underdevelopment. Furthermore, unequal access to these alternatives risks reinforcing social and economic hierarchies, exacerbating disparities between rural and urban populations, as well as along ethnic and socio-political lines. Policymakers must engage with the root causes of these structural shifts, ensuring that institutional reforms not only restore trust but also foster sustainable, inclusive economic frameworks that address the specific historical and socio-political realities of the North West Region.

4.3. Informal Trade Networks: Defiance, Adaptation, and Resilience in the North West of Cameroon

The protracted Anglophone crisis in Cameroon has catalyzed the expansion of informal trade networks, transforming them into both economic survival mechanisms and sites of socio-political defiance. These networks emerge at the nexus of state repression, economic necessity, and defiant scholarship, challenging conventional frameworks of governance and control. Contrary to state expectations, crackdowns on economic activities have not quelled informal trade but have, instead, entrenched its presence as an adaptive strategy of resistance.

The 2018 closure of the Ekok border was a turning point in the restructuring of trade flows in the region. Rather than suppressing economic activity, the border closure accelerated the growth of clandestine trade corridors and decentralized market structures. Traders rapidly adjusted supply chains, leveraging under-monitored routes and communal networks to evade state-imposed economic restrictions. According to Enoh (2024), a veteran trader,

“When the government shuts down official trade, we create our systems. We adapt.”

This reconfiguration of trade routes exemplifies what defiant scholarship terms “pragmatic resistance” a form of economic disobedience that subverts state authority through persistent, nonviolent adaptation rather than confrontation.

These dynamics align with Bayart’s (1993) notion of the “politics of the belly,” wherein economic survival is inseparable from political subversion. By operating beyond state oversight, informal trade networks expose the limits of state control while reaffirming the autonomy of Anglophone economic actors. With an estimated 40% of households in conflict-affected areas dependent on informal trade (Talla, 2024), these networks constitute not merely alternative economic structures but pillars of resilience amid state neglect and economic precarity.

4.3.1. State Repression and the Unintended Reinforcement of Informality

Despite increased state intervention, including military blockades, curfews, and intensified border surveillance, informal trade networks continue to thrive. The state’s efforts to restrict economic flows ostensibly aimed at curbing separatist funding have instead exacerbated local distrust in formal institutions and emboldened economic noncompliance. Traders such as Tabe (2024), operating in Bamenda, report frequent encounters with military extortion, yet continue cross-border operations despite heightened security risks.

Rather than dismantling informal economies, state repression has inadvertently reinforced their significance as alternative economic spaces. This paradox reflects broader tensions in African political economies, where state interventions drive economic actors further into informality. Mkandawire, (2001) argues that attempts to impose rigid economic regulations on marginalized communities often fail due to the state’s inability to provide viable economic alternatives. In the case of Cameroon, informal trade networks are not merely economic adaptations but also expressions of political dissent manifesting as collective acts of defiance against an exclusionary state apparatus.

4.3.2. The Anglophone Crisis and the Political Economy of Informality

The evolution of informal trade networks within the Anglophone crisis underlines their dual role in economic survival and political resistance. Increasing reliance on cross-border trade with Nigeria, coupled with targeted economic boycotts of state-affiliated businesses, illustrates a deliberate shift away from state-controlled economic circuits. This transition is not simply a byproduct of conflict; rather, it represents a strategic economic disengagement from a political system perceived as repressive and unrepresentative.

As Paul (2024), a trader from Kumbo, explains,

“Choosing where we trade is a political decision. When we take our goods to Nigeria instead of Douala, we are making a statement.”

This phenomenon resonates with Murrey’s (2024) concept of “slow dissent,” where everyday economic practices serve as incremental acts of resistance. Informal trade networks thus become more than economic survival tools they are vehicles of self-determination that challenge centralized state authority. However, these networks also reveal internal complexities, particularly in their adaptation to modern financial tools such as mobile money platforms, which coexist with traditional market practices, signaling an evolving but contested economic landscape.

4.3.3. Challenges of Sustainability and Inclusivity

Despite their resilience, the long-term sustainability of informal trade networks is precarious. One major challenge is the heavy reliance on diaspora remittances, which contribute an estimated 25% of household incomes in Bamenda (Talla, 2024). This dependency exposes traders to external economic fluctuations, particularly downturns in host countries where the Anglophone diaspora is concentrated. A decline in remittances could significantly undermine the economic viability of informal networks, necessitating local strategies for greater financial self-sufficiency.

Additionally, the inclusivity of these networks remains a contentious issue. While they provide economic alternatives for many, disparities persist, particularly among rural traders and smaller ethnic groups who face systemic marginalization even within resistance economies. Interviews with figures such as Njang (2024), a trader from the Nso ethnic group, highlight concerns over unequal access to trade routes and market opportunities.

“They say these networks are for all Anglophones, but if you’re from a village or a smaller tribe, you face more checkpoints, higher ‘taxes,’ and fewer connections. My Nso peers are stuck selling basic goods in local markets, while others dominate cross-border trade.”

Such accounts reveal how exclusionary practices rooted in geography, ethnicity, and power dynamics undermine the solidarity these networks claim to foster. Without intentional reforms to address these inequities, informal trade risks replicating the very hierarchies it emerged to resist. For economic resistance to translate into lasting transformation, it must prioritize equitable access and dismantle internal barriers that perpetuate historical marginalization.

4.3.4. Rethinking Informality as a Site of Political Contestation

Informal trade networks in the North West of Cameroon transcend conventional economic categorization; they are deeply embedded in political contestation, cultural assertion, and community resilience. Their persistence, despite state repression, highlights the limitations of coercive economic policies while reaffirming the agency of marginalized communities in crafting alternative economic futures. However, their sustainability requires more than resilience it demands strategic adaptation that balances economic survival with political effectiveness.

This study emphasizes the necessity of viewing informal economies not as disruptions to state authority but as legitimate socio-political spaces that reflect localized forms of governance and autonomy. Future policy interventions must move beyond suppression, recognizing informal trade networks as vital components of economic stability. By integrating community-driven economic frameworks with broader resistance strategies, the Anglophone movement can ensure that economic disobedience remains a tool of empowerment rather than an inadvertent instrument of exclusion.

4.4. Cultural Dimensions of Economic Disobedience in the North West of Cameroon

The ongoing socio-political crisis in the North West region of Cameroon has not only reshaped political discourse but has also catalyzed economic resistance as a form of cultural and political defiance. This economic disobedience manifested through boycotts, informal trade networks, and localized financial self-reliance transcends mere economic pragmatism. It functions as a deliberate postcolonial contestation against the Francophone-dominated state apparatus. More importantly, these acts of resistance are deeply embedded within the broader Anglophone struggle for cultural autonomy, reinforcing economic agency as a means of asserting self-determination and preserving identity.

4.4.1. Economic Disobedience as Cultural Defiance

Economic disobedience in the North West region extends beyond mere financial survival strategies; it embodies a collective cultural and political response to systemic marginalization. The deliberate avoidance of state-controlled financial institutions, reliance on informal trade mechanisms, and the refusal to participate in government-led economic initiatives are ways in which local communities reclaim a degree of sovereignty. By undermining the economic structures imposed by the central government, these communities articulate their resistance against decades of socio-political alienation.

At the heart of this economic resistance is the assertion of an Anglophone identity that seeks to counter the dominant Francophone economic and political structures. The use of informal savings groups, community-based bartering, and cross-border trade with neighboring Nigeria reflect an economic philosophy rooted in indigenous knowledge systems and pre-colonial economic traditions. This defiant economic behavior thus serves as an expression of cultural resilience, where local actors navigate financial autonomy within the constraints of political oppression.

4.4.2. Tensions Between Traditional Governance and Modern Resistance

However, the economic resistance movement is far from monolithic. Within the North West region, traditional governance structures often exhibit ambivalence toward these acts of economic disobedience. While some traditional chiefs openly endorse the movement, seeing it as a legitimate means of resisting state oppression, others express concerns over the broader social and economic implications of prolonged boycotts and informal trade disruptions.

As Chief Ebong (2024) of the Ngoketunjia division explains:

“While I understand the desire to resist, these boycotts disrupt the peace and harmony in our communities. As chiefs, we are bound by tradition to ensure the well-being of our people, and such actions sometimes create divisions.”

This perspective accelerates the inherent tensions between customary authority and modern political insurgency. Traditional leaders, who have historically played a mediatory role in conflict resolution, find themselves navigating a complex landscape where economic resistance is both a tool for liberation and a source of societal fragmentation. The dilemma highlights the need for a nuanced approach to economic disobedience one that considers both the aspirations for self-determination and the imperative of social cohesion.

4.4.3. Interethnic Dynamics and the Need for Intersectionality

Another critical dimension of economic resistance in the North West of Cameroon is its framing within an overarching Anglophone identity. While the movement seeks to unify all English-speaking Cameroonians under a common cause, this broad narrative often overlooks significant intra-regional cultural differences. Ethnic groups within the North West region, such as the Nso, Kom, and Wimbum, each have distinct socio-economic traditions and perspectives on the crisis. The homogenization of Anglophone resistance can inadvertently marginalize these diverse voices. As Njang, a member of the Nso ethnic group (2024), notes:

“The fight is for all Anglophones, but not all of us see it the same way. Some groups, especially in rural areas, feel left out. The broader movement doesn’t always reflect our values.”

This critique calls for a more intersectional approach to economic resistance one that acknowledges and incorporates the varied ethnic and cultural identities within the Anglophone struggle. Addressing these differences is crucial for ensuring that the movement remains inclusive and reflective of the lived realities of all its participants.

4.4.4. Economic Resistance as a Negotiation of Identity

The economic disobedience witnessed in the northwest of Cameroon is far more than a reaction to economic hardship; it is a strategic cultural resistance that emphasizes the ongoing struggle for identity, autonomy, and self-determination. However, the movement must navigate internal complexities, including the role of traditional governance structures and the need for greater inclusivity in its approach to interethnic diversity.

As the crisis persists, economic disobedience will likely continue to evolve, shaping and reshaping the cultural landscape of resistance in the region. Whether through informal trade, financial self-reliance, or economic boycotts, the people of the North West are not only resisting economic marginalization but also actively redefining the contours of their cultural and political identities in the process.

4.5. The Role of the Cameroonian Diaspora and Informal Economies in Resistance

4.5.1. Diaspora Remittances as Economic Resistance

The Cameroonian diaspora has emerged as a cornerstone of economic resistance in the crisis-ridden North West region, channeling vital resources through informal networks to circumvent state-imposed economic blockades and violence. As formal markets collapsed under the strain of conflict, diaspora remittances became a lifeline, sustaining households and enabling informal trade to thrive. Talla (2024) estimates that at the peak of the crisis, these remittances accounted for 25% of household incomes in Bamenda, highlighting their critical role in keeping local economies afloat. The transnational flow of funds has not only stabilized livelihoods but also fueled defiance against systemic marginalization. Fonkwa, a market leader in Bamenda (2024), captures this dynamic:

“Without the support from our brothers and sisters abroad, many of us would not have survived. The shops would have closed, and families would have struggled even more. Their money isn’t just cash it’s a message that we’re not alone in this fight.”

This sentiment reflects how remittances transcend mere financial aid, embodying solidarity and resistance. However, the sustainability of this model is fraught with contradictions. While diaspora contributions empower communities to bypass state control, they also tether local economies to external vulnerabilities. For instance, the 2023 dip in remittances was partly attributed to new bureaucratic hurdles imposed by the government, such as mandatory national ID verification for recipients a near-impossible requirement for many displaced or rural households lacking official documentation. Ngum, a small-scale trader in Bamenda, described the fallout during fieldwork interviews:

“Last year, when the government demanded new papers to receive money from abroad, my cousin in Germany couldn’t send funds for months. I couldn’t restock my stall, and some of us sold goods at a loss just to eat. If they keep blocking how will our diaspora helps us, how will we survive?”

Ngum’s testimony underscores how state policies intentionally or unintentionally disrupt the lifelines sustaining informal resistance economies. By constraining access to remittances, these reforms weaken the financial autonomy of Anglophone communities, pushing traders toward riskier informal channels (e.g., wemoneyCrypto transfers) that are slower, costlier, and more susceptible to interception by security forces.

To mitigate these risks, scholars and grassroots organizers stress the urgency of diversifying informal economies. This includes investing in localized production, such as community farming cooperatives, and strengthening intra-regional trade alliances to reduce dependency on imported goods. As Fonkwa notes:

“We need to grow what we eat, make what we use. The diaspora’s help is precious, but our survival can’t hang on their sacrifices forever. Real resistance means building systems that don’t collapse when the world shakes.”

Such shifts would not only enhance resilience but also recenter agency within Anglophone communities. For economic resistance to evolve into enduring transformation, it must balance diaspora solidarity with strategies for self-reliance transcending survival to foster sovereignty.

4.5.2. Comparative Lessons from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

Cameroon’s resistance economy can be further contextualized through a comparative analysis with informal economies in conflict-affected regions, such as the DRC. In the DRC, informal economic networks have partially integrated with localized governance structures, ensuring greater economic resilience. As Omasombo (2016) notes:

“Local governance structures in conflict zones have enabled informal markets to become more integrated into the larger economy, providing stability and reducing reliance on external funding.”

In contrast, Cameroon’s informal economies remain largely outside formal regulatory frameworks, making traders vulnerable to state crackdowns and military extortion. Ngwa, a farmer in Bambili (2024), illustrates this challenge:

“We have no official market spaces, no licenses, and sometimes, the military comes to demand bribes to let us pass with our goods. If there were a way to formalize our activities, things would be much easier.”

To enhance economic sustainability, some local leaders in Ndop have begun exploring semi-formal economic structures, integrating informal markets with regional and international supply chains. As Fomunung, a community organizer (2024), asserts:

“We are looking into ways to organize and protect ourselves without relying too much on external help. If we can formalize our markets and work with each other, we can build a stronger foundation.”

This transition from survivalist economies to resilient economic networks suggest a pathway toward economic self-determination, where local actors take ownership of their financial futures without state interference.

The cultural dimensions of economic disobedience in Cameroon’s North West region demonstrate that resistance is both an economic and cultural phenomenon. Acts of economic insurgency, including boycotts and informal trade, serve as expressions of postcolonial defiance and cultural autonomy. However, internal tensions between modern resistance and traditional governance, between urban and rural actors, and between local economies and diaspora remittances highlight the complexities of resistance movements.

A comparative perspective with the DRC reveals the potential for semi-formal economic structures to ensure long-term sustainability. Moving forward, the challenge lies in balancing economic autonomy with resistance principles, ensuring that informal economies evolve into resilient economic systems while preserving the integrity of the Anglophone struggle.

By addressing these internal contradictions and strategically evolving its economic resistance framework, Cameroon’s Anglophone communities can fortify their autonomy while safeguarding their cultural heritage.

4.6. Gendered Dimensions of Resistance in the North West of Cameroon

4.6.1. Grassroots Economic Resistance and Women’s Agency

The gendered dimensions of economic resistance in the North West of Cameroon during the Anglophone Crisis reveal the resilience and defiance of women amidst systemic marginalization. Grounded in defiant scholarship, this analysis examines how women’s economic initiatives challenge state authority and hegemonic structures while addressing local needs. Amidst escalating militarization and governance collapse, women’s grassroots efforts, such as the Bamenda Women’s Market Cooperative, exemplify indigenous solidarity and resource-sharing practices essential for survival. As Mavis, a cooperative leader, notes, “We pool money to buy goods, and when someone’s business is affected, we help them.” These actions underline women’s agency as both economic innovators and political actors resisting marginalization through informal trade networks and alternative economies.

4.6.2. Defiant Scholarship: Women’s Resistance and the Impact of Militarization

From the perspective of defiant scholarship, grassroots initiatives like these represent more than mechanisms of economic survival. They constitute acts of resistance that subvert state control and repression. Informal savings groups, rotating credit systems, and clandestine trade networks are evidence of how women navigate oppressive systems with remarkable ingenuity. For instance, women traders in Ngoketunjia and Bui Divisions have developed intricate cross-border trade routes with Nigeria to bypass military checkpoints, thereby maintaining access to essential goods. These adaptive strategies highlight women’s agency in resisting state economic repression. Yet, these acts of defiance are not without significant consequences. As Grace, a trader in Bafut, explains, “Soldiers come to the markets, demanding bribes. If we refuse, they take our goods or intimidate us.” This dual burden of economic precarity and physical insecurity reflects the compounded vulnerabilities women face as they operate in militarized and volatile environments.

4.6.3. Gendered Barriers and Policy Recommendations for Supporting Women’s Resistance

The Anglophone Crisis exacerbates these dynamics, making it essential to center the lived realities of women in towns such as Bamenda, Kumbo, and Ndu. The conflict has deepened financial exclusion, with rural women facing stringent loan requirements, exorbitant interest rates, and the closure of local banks due to insecurity. Alice, a small-scale trader, emphasizes this exclusion: “Even when we have a good business idea, it’s hard to get funding. The banks don’t trust us, and if we find a loan, the interest is too high.” This exclusion forces women into precarious informal networks that, while vital for survival, lack scalability and stability. Compounding these economic challenges is the intersection of gendered violence and economic resistance. Women’s visibility as economic actors make them prime targets of harassment and exploitation by both state forces and separatist groups. The militarization of public spaces, coupled with the perception of women as economic providers, has rendered them especially vulnerable to violence. As Grace explains, “We are easy targets for both sides. Soldiers want bribes, the separatists accuse us of betraying their cause, and sometimes, we are attacked by both sides.” To fully integrate the principles of defiant scholarship into this analysis, women’s economic resistance must be situated within broader critiques of power and marginalization. Grassroots initiatives challenge traditional narratives of resistance, which often privilege male-dominated armed conflict, offering a more nuanced understanding of agency in conflict-affected contexts. Informal boycotts, clandestine trade networks, and collective savings systems extend the scope of what constitutes resistance (Scott, 1985; Pommerolle & Heungoup, 2017). For example, women in Ndop have organized informal boycotts of state-sanctioned markets, thereby withdrawing from government-controlled economic systems as a form of protest against militarization and repression. These acts of defiance highlight the intersection of women’s economic activities with political resistance, contesting both state oppression and patriarchal norms that have historically excluded them from positions of power and influence (Amin, 2021; Anchimbe, 2018). Addressing the invisibility of women in academic and policy discourses is critical to amplifying their contributions to resistance and resilience in the North West. Defiant scholarship urges a reexamination of dominant narratives, prioritizing women’s voices in shaping solutions to the Anglophone Crisis. Policies that enhance women’s access to gender-sensitive financial resources, such as microfinance initiatives tailored to conflict zones, would enable them to scale their economic activities and strengthen their resistance efforts. Additionally, measures to protect women from gender-based violence in markets and public spaces are essential for creating safer environments where women can thrive. Supporting cooperatives such as the Bamenda Women’s Market Cooperative and recognizing informal trade networks as legitimate economic systems would empower women and challenge state economic repression and neglect of marginalized communities.

4.7. Discussion Rethinking Economic Disobedience: Resistance and Governance in Cameroon’s North West Region

Economic disobedience in Cameroon’s North West Region is far more than a reaction to economic exclusion; it is a deliberate and sustained political intervention that challenges the very legitimacy of state authority. Boycotts, informal trade networks, and tax evasion serve as mechanisms through which marginalized communities assert agency, rejecting centralized control and constructing alternative economic spaces. These grassroots strategies function at the intersection of economic survival and political defiance, where necessity fuels a broader ideological contestation of state power. The proliferation of informal markets, for instance, does not simply alleviate deprivation it actively disrupts state-imposed economic hierarchies, signaling a profound refusal to comply with structures perceived as illegitimate.

The rise of resistance economies carries critical governance implications. While fostering economic resilience and reinforcing local solidarity, these informal networks simultaneously undermine state fiscal capacity, weakening the financial foundations of governance. The redirection of trade flows toward Nigerian markets and the circumvention of state taxation exacerbate the disintegration of formal economic structures, entrenching parallel economies that operate outside state control. This fragmentation compounds Cameroon’s governance crisis, where state institutions already struggle with legitimacy deficits and systemic exclusion.

Addressing these dynamics requires a radical departure from conventional governance models. Policymakers must recognize the futility of imposing rigid, centralized economic structures on communities that have long been disenfranchised. Instead, an adaptive framework, one that legitimizes grassroots economic agency while integrating informal networks into decentralized governance offers a viable path toward stability. This demands a paradigm shift: resistance economies should not be viewed as threats but as potential catalysts for equitable reform. By bridging the gap between state structures and local economic practices, Cameroon can transform grassroots resistance into a foundation for inclusive governance, fostering national cohesion while preserving economic autonomy.

4.8. Conclusions

Economic disobedience in Cameroon’s North West Region is not merely a response to economic marginalization but a profound act of political defiance that reconfigures power relations in a contested space. Boycotts and informal trade networks function as strategic tools through which Anglophone communities reject centralized authority, subvert state control, and assert alternative modes of governance. These practices transcend economic necessity to embody a deeper ideological struggle one that interrogates the legitimacy of state structures and reclaims autonomy from a system historically designed to suppress Anglophone agency.

This study critically examines the intersection of economic agency and political resistance in a postcolonial context, highlighting the limitations of conventional governance frameworks in addressing systemic exclusion. The failure of the Cameroonian state to integrate these grassroots economic strategies into formal governance perpetuates cycles of marginalization and conflict. Sustainable political stability requires a paradigm shift one that prioritizes decentralization, economic self-determination, and the inclusion of local actors in decision-making processes.

Beyond Cameroon, this analysis offers a comparative framework for understanding resistance economies in other politically volatile postcolonial states. By bridging political economy, sociology, and critical historiography, future research must explore how informal economies function not just as survival mechanisms but as catalysts for transformative governance and social reconfiguration.

References

- Agubamah, E. (2023). The impact of Anglo-phone Cameroonian Crisis on Nigeria. Journal of Political Discourse, 1(1), 14.

- Ako, E. (n.d.). Effects of Anglophone crisis on employees’ work engagement before and during: A comparative analysis in The University of Bamenda.

- Amin, J. A. (2021). President Paul Biya and Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis: A catalog of miscalculations. Africa Today, 68(1), 95–122. [CrossRef]

- Ambe, G. (n.d.). Cameroon Anglophone genocide: Past, present and future. Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2, 22–33.

- Anchimbe, E. A. (2018). The roots of the Anglophone problem. Current History, 117(799), 169–174.

- Asangna, C. (2023). Investigating the origin, elements, and motivations of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon. Global Politics and Current Diplomacy (JGPCD), 5.

- Bayart, J.-F. (1993). The state in Africa: The politics of the belly. Longman.

- Bertrand, A. L. A. H. (2020). The socio-economic consequences of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon (November 2016–August 2019), a cause for an indispensable concern. GSJ, 8(11).

- Beseng, M. Crawford, G., & Annan, N. (2023). From “Anglophone problem” to “Anglophone conflict” in Cameroon: Assessing prospects for peace. Africa Spectrum, 58(1), 89–105. [CrossRef]

- Ekah, R. E. (2020). The Anglophone crisis in Cameroon: A geopolitical analysis. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3529815.

- Eyoh, D. (1998). Conflicting narratives of Anglophone protest and the politics of identity in Cameroon. Journal of African Political Economy, 24(2), 123–145.

- Fon, N. N. A., Achu, N. N., & Formella, C. N. (2024). Whose right is right? The dialectics of remedial secession and territorial sovereignty in the Cameroon Anglophone crisis. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Gbemudia, R. U., & Cho, D. T. (2024). The Anglophone Cameroon conflict and the responsibility to protect. In Africa’s engagement with the responsibility to protect in the 21st century (pp. 127–145). Springer Nature Singapore.

- Iyal, O. H., Elizabeth, N., & Baiye, E. G. (2024). A legal appraisal of the causes of the Cameroon Anglophone crisis. Studies in Social Science & Humanities, 3(9), 1–20.

- Ketzmerick, L. (2023). The Anglophone crisis in Cameroon: Local conflict, global competition, and transnational rebel governance. Global Conflict Studies Quarterly, 5(2), 153–177.

- Konings, P. (2011). The politics of neoliberal reforms in Africa: State and civil society in Cameroon. Langaa RPCIG.

- Mateş, R. (2019). Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis: Analysis of the political, socio-cultural and economic impact. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai-Studia Europaea, 64(2), 261–278.

- Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. University of California Press.

- Menyoli, G. I. (2021). The Anglophone crisis in Cameroon [Master’s thesis, UiT Norges arktiske universitet].

- Mkandawire, T. (2001). Thinking about developmental states in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(3), 289–313.

- Murrey, A. (2024). Slow dissent and worldmaking beyond imperial relations in “Kamer-amère” (Bitter Cameroon). International Studies Quarterly, 68(2), sqae058. [CrossRef]

- Musah, C. P. (2022). The Anglophone crisis in Cameroon: Unmasking government’s implication in the radicalisation of the crisis. African Journal of History and Archaeology, 6(1), 22–38.

- Nwati, M. T. (2020). The Anglophone crisis: The birth of warlords, the impact of warlords activity on the people of North West and South West Region of Cameroon. Advances in Applied Sociology, 10(5), 157–185. [CrossRef]

- Nyamnjoh, F. B. (1999). Cameroon: A country united by ethnic ambition and difference. African Affairs, 98(390), 101–118. [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C. N. E. (2018). Analysing Cameroon’s anglophone crisis. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 10(3), 8–12.

- Omasombo Tshonda, J. (Ed.). (2016). Beni-Butembo : Défis et résilience dans un espace en crise. Cahiers Africains (No. 95-96). Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Olinga, M. (2023). The Cameroon “Anglophone crisis”: From international to national fault lines. Postcolonial Cultures Studies and Essays, 2, 22–40.

- Peace, P. W. S. (2020). Easing Cameroon’s ethno-political tensions, on and offline. Journal of Global Politics and Culture, 12(4), 85–103.

- Pommerolle, M. E. Pommerolle, M. E., & Heungoup, H. D. M. (2017). The “Anglophone crisis”: A tale of the Cameroonian postcolony. African Affairs, 116(464), 526–538. [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. C. (1985). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. Yale University Press.

- Talla, P. (2024). Culture or power: The eruption of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon. Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 45(3), 211–229. [CrossRef]

- Willis, T., Angove, A., & Mbinkar, S. (2020). “We remain their slaves”: Voices from the Cameroon conflict. African Studies Review, 63(1), 101–120. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).