1. Introduction

The emergence of the neoliberal project (Neoliberalism is a historical version of capitalism, a form of society based on the exploitation of one class by another (Davidson, 2018).) in the early 1980s, and its intensification in the 1990s, marked a watershed moment in the counter-attack against the welfare state. This project, spearheaded by the international capitalist class (ICC) in imperial powers, including owners of multinational corporations (MNCs) and international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and backed by imperial superpowers, primarily the United States (US), helped dismantle the welfare liberal state regime. In doing so, it restructured the global economy to better serve the needs of ICC rather than welfare of poorer countries. This aligns with Davies and Bansel’s (2007) argument that the neoliberal project involved a “dramatic shift in government commitments, from one that was responsible for the national interest to one that serves global (over local) capital accumulation and makes people productive economic entrepreneurs of their lives.

Monbiot (2016, p. 2) takes a similar position, claiming that:

“Never mind structural unemployment: if you don’t have a job, it’s because you are enterprising. Never mind the impossible costs of housing: if your credit card is maxed out, you’re feckless and improvident. Never mind that your children no longer have a school playing field: if they get fat, it’s your fault. Never mind inequality because the market ensures that everyone gets what he/she deserves and thus efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The rich get richer by merit(In that, neoliberal project ignores the advantages such as education, inheritance and class that may have helped to them secure it. In that refuse to understand how within one country one class can enrich itself at the expense of another). The Poor should blame themselves for their failures. In a world governed by unfettered market, those who fall behind become defined and self-defined as losers”.

According to the foregoing, the survival of the people—particularly the underclass, the socially excluded, marginalized, and disadvantaged—is completely dislocated from the welfare state and left at the mercy of the unfettered market, which Bettache, Chiu, and Beattie (2020) describe as a “dog-eat-dog society.” The neoliberal enterprise is founded on selfishness and greed rather than cooperation, shared economic prosperity, reciprocity, and altruism (Hayat et al., 2021). That is the ideological project that seeks to legitimize and justify the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the capitalist class of the core (Carroll et al., 2019). Proponents of this project claim that the best way to prosperity is for individuals to seek their own self-interests, and that free markets are the only way to achieve this.

Neoliberalism, which draws from classical liberal ideas advocated by economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, emphasizes the importance of open markets. It offers a political and economic framework that supports the global application of comparative advantage theory (CAT). For example, according to Ricardo’s CAT, each country should specialize in the exploitation, manufacturing, and exportation of goods for which it is naturally or historically best equipped (Gonzalez, 2006). For example, countries with abundant natural resources but limited capital should focus on raw material production, while countries with a skilled labor force should specialize in high-value-added products. At its core, the CAT advocates for an equitable playing field where any nation—whether rich or poor—can benefit from international trade, as long as government involvement in the market is minimal or limited to exceptional cases.

However, similar to how CAT was used to justify the exploitation during the colonial era, neoliberalism has and continue to be employed in the post-colonial era to legitimize and normalize the exploitation and domination of developing countries (DCs) by foreign forces such MNCs and IFIs. Both systems—neoliberalism and colonialism—ultimately share outcomes of economic exploitation, cultural imposition, and political subjugation (Gonzalez, 2006). Like CAT, neoliberal theory left African countries with little room to pursue alternative paths of development that might better suit their needs. CAT has imposed foreign standards without acknowledging the poor countries’ context. Neoliberalism has reinforced this by promoting market-driven development models that do not prioritize social welfare or local conditions of the DCs.

Proponents of neoliberalism argue that the reduction of the role of the state in the economy, encouraging privatization, and allowing market forces to dictate economic outcomes is the best policy. In particular, government involvement in trade and industry distorts price signals, leading countries to specialize in areas where they lack comparative advantage. However, the reduced role of the state weakened its capacity to implement development policies that could address structural issues in education, health, infrastructure, and poverty. More importantly, a closer examination of capitalism’s history, as Chang (2002) suggests, reveals a different story. He argues that free trade imperialism distorts our understanding of the past, present, and future.

This is because when a country achieves success, it often removes the ‘ladder’ that helped it rise, thereby preventing others from following the same path.

By removing the ladder—aptly called industrial policy—rich nations safeguard their industries from competition, ensuring their continued dominance in global markets and the ongoing flow of capital from developing to the rich ones. In other words, they maintain dominance by shaping global economic rules that allow them to extract wealth and resources from poorer nations while limiting their opportunities to employ similar strategies for fostering their own industrial growth. This is referred to as “policy hypocrisy.” In particular, its focus on export-oriented economies and the exploitation of natural resources, neoliberalism has led to economic dependency, environmental degradation, and little value-added production in peripheral countries. This has hindered the development of diversified, sustainable economies that can provide jobs and raise living standards for all citizens.

More specifically, national comparative advantage is not simply a byproduct of nature, as preached by the proponents of neoliberalism, but a strategic creation, influenced by policy decisions and investments that enable countries to compete in the global economy on their own terms. That is, national comparative advantage is created, not grown from a country’s natural endowments, as neoliberalism insists (Porter, 2011). It is, rather, fostered through pressure for innovation, investment in research and development, deepening skills and knowledge, investment in products and processes, building clusters, and promoting domestic rivalry. It has evolved and accelerated over time in response to strategic government interventions. These interventions are typically designed to support industries essential for national economic development or to help emerging sectors that might face difficulties competing in the global marketplace.

From the above, the reality is that free trade was made possible not by market forces, but by efficient government intervention that created the necessary environment for companies to gain a competitive advantage. As discussed earlier, market outcomes are significantly shaped by public policies, such as those related to education and legal protections. In each of these areas, there is important work to be done through public action, which can substantially influence both local and global economic relations (Lechner & Boli, eds., 2020). Since remaining marginalized is not an option, DCs must take action to accelerate their development.

In fact, the economic success of super-capitalist countries can never be credited to free trade, because they never implemented it before becoming industrial and technological leaders. Both Germany and the US knew that Britain had risen to the top through protectionism and subsidies, not free trade, and that they, too, needed to do the same to reach their current positions. However, Britain preached free trade to Germany and the US when they were less advanced, but to them, it sounded like someone attempting to ‘kick away the ladder’ with which they had risen to the top (Chang, 2010). However, after attaining international comparative advantage in industrial power and capital goods (after World War II) behind protective walls against Britain, the US not only preached free trade, as the UK did, but imposes it on peripheral countries.

The US recognizes that it would benefit if the rest of the world, particularly peripheral countries, opened their markets to its MNCs. This aligns with the views of Braithwaite (2019) and Gonzalez (2006), who argue that Washington econocrats understood that while a collapse in business regulation is detrimental to America, it benefits American MNCs when other countries avoid imposing regulatory burdens on American investments and exports. In this context, governments outside the imperial powers act as agents of neoliberal policy enforcers, rather than as referees who actively intervene to enforce market rules, nurture markets, and penalize anti-competitive behavior. Carroll, Gonzalez-Vicente, and Jarvis (2019:12) synthesize this as follows:

powerful fractions of domestic capital in the North increasingly delinked from the nation state as a development ‘container’ and strive to became transnational in their focus, reorganizing production (and sometimes domicile) and accessing new markets. Indeed, the interests that stood to benefit from neoliberalism and its promotion reflected the most powerful fractions of capital in the global political economy– multinational enterprises (MNEs) that were/are able to leverage off their dominance in the latest means of production, including those elements enmeshed at important nodes of what are now commonly described as ‘global production chains’ or ‘global value chains.

From the above, foreign policy of today’s development model (RNPs) shapes the origin country’s comparative advantage at the expense of the targeted countries. It cannot be a zero-sum game as it restricts the development options available, shaping global trade rules, controlling access to capital (technology), imposing standards that are out of context for the targeted countries. All of these lead to “a global economic playing field” that only favors powerful countries.

A good example here is the trade and investment treaties, and lending conditions, negotiated by powerful countries which aim to open foreign opportunities such as natural resources for their own MNCs while protecting their sensitive sectors at home. These factors strip away domestic tools for creating domestic comparative advantage leaving these countries dependent on natural resources and foreign capital.

In fact, economic literature is full of evidence that, imperial countries survived and thrived not through natural competition but by exploiting unfair policies rooted in systems of economic, political and military coercion or simply jungle effect to maintain their dominance. For example, the wealth generated from colonial exploitation and unjust trade practices allowed European countries to monopolize global resources, leaving colonized countries impoverished and unable to compete on an equal footing. The legacy of these practices continues to shape global inequality and the modern international system. Klein, Naomi (2007) contends that colonialism strategies, particularly the exploitation of crises to impose RNPs on vulnerable countries, have influenced the development of modern capitalist systems.

In fact, neoliberalism, just like colonialism, emerged in response to the profitability crisis and overproduction of the 1970s, aiming to reopen peripheral markets for exploitation. Thus, the RNPs are ideological projects aimed at legitimizing and justifying the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the capitalist class in the Global North. Singh (2022) argues that neoliberalism was developed to reverse this decline and restore capitalist profitability.

Neoliberalism was imposed on debt-ridden African nations through structural adjustment programs (SAPs), fittingly known as the “Washington Consensus”. This arose as a reaction to the structural issues, specifically the commodity/debt crisis triggered by the profitability crisis (led to a decline in demand for African commodity exports and consequently reduced government revenues) that followed the Golden Age of consumerism (1950s-1970s) in the core (Singh, 2022). The crisis has been attributed to the so-called “lack of organizational flexibility” or “labor market rigidity” (Harvey, 2007; Davies, 2014; Davies et al., 2021; Marois & Pradella, 2015; Durand, 2004). Neoliberal supporters used the debt crisis, which was mostly externally driven, to reopen African economies to outside exploitation in an attempt to salvage capitalism. According to Singh (2022, p. 4), the crisis gave an opportunity for Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek to apply previously ignored neoliberal policies.

Thus, imperial countries aiming to (re)penetrate the nationalist economies of the periphery through multinational institutions while remaining unregulated and tax-free reflected the neoliberal agenda as a natural right to build a borderless world. Neoliberalism institutionalized the core’s drive to expand markets and dominate the periphery. Frimpong (2020) contends that neoliberalism can cause monopolies with diminishing profits to relocate outside of their own nations, reversing the trend through financialization. However, as profitability crises worsened and exacerbated commodity and debt crises, African countries were forced to unconditionally embrace the neoliberal project in the 1980s in order to renegotiate desperately needed new loans (Kentikelenis & Babb, 2019) and address both short-term public deficits and public expenditures.

Indeed, in the face of resistance, the use of force-maintained order independent of the anticipated outcome (Marois & Pradella, 2015; Siddiqui 2022). Schwabach and Cockfield (2010), ironically, argue that economic elites have a moral right to assassinate their rulers and form governments that respect their inherent rights. As a result, the adoption of neoliberal policy prescriptions such as smaller government, deregulation, liberalization, budgetary discipline, and privatization forces African countries to enter the free market economy before reaching a level of industrial development at which their industries can survive (Husain, 2022). In keeping with this, firms with a big amount of capital, such as MNCs, gain a competitive edge through higher productivity, allowing them to drive non-competitive enterprises out of business or be acquired by competitors. This intense struggle for survival, takeovers, and mergers resulted in monopolies, the final stage of capitalism (Frimpong, 2020). Because monopolies can control output and price, profits will increase as the system evolves. This suggests that the time of falling profits will be replaced by an increase in surplus value. This is because, monopolies divert from price-cutting and price wars, which neoliberals regard as self-defeating, to non-price competition-marketing and sales strategies (Frimpong, 2020).

From the above, neoliberalism replaces people’s power with that of capital and businesses. Unfortunately, neoliberalism has been tremendously successful not just in doing so, but also in establishing a hegemonic hold on African economies and ensuring unrestricted resource flow from the former to the latter. This is what Monbiot (2016) referred to as “let the able rise and the weak perish”. This occurred because rather than addressing the problem of structural changes in African economies, which should be subject to internal rationalities and needs, the neoliberal policies have subjected these economies to external rationalities and needs, imposing internal solutions to problems with external origins as previously mentioned. Consistent with this, Harvey (2007) demonstrated that the restoration of capital accumulation and power in dominating power countries relies tremendously on surplus extracted around the world, including Africa, under neoliberal rules of the game.

In fact, the radical neoliberal SAPs and its subsequent reforms such as the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs) launched in 1996 in response to critics of SAPs, Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) in 1999 which intended to overhaul the HIPCs initiatives (Bond, & Dor, 2003; Heidhues et al., 2011; & Mkandawire, 2005), United nations (UN) Millennium Developing Goals (MDGs) (2001-2015), which emerged from the critics of the previous neoliberal reforms (De La Barra, 2006) and finally the age of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (2015-2030) which were also informed by the critics of MDGs (Gabay, & Ilcan, 2017; Oluwashakin, & Aboyade,2021, Durokifa et al., 2018), are implemented as if there is no alternative. Shields (2020) stated that there are always neoliberal remedies to neoliberal reform critics, and the goal appears to be indestructible.

In contrast to the preceding analysis, the dominant assumption is that implementing neoliberal policies would not only accelerate economic growth and development, but would also serve as a means to end Africa’s marginalization from globalization by encouraging foreign investment and the expansion and diversification of exports (Mkandawire 2005). However, history has demonstrated that countries can accomplish the aforementioned desirable outcomes through intentional, selective, and strategically sound integration into the global economy, rather than unconditional integration, as recommended by the New Washington Consensus (NWC). Otherwise, imperial countries seek to rebuild the global system for their own gain rather than the advantage of others (Arestis & Sawyer, 2000).

As a result, empirical research into the theoretical claims mentioned above is critical. While RNPs have shaped development strategies in DCs through SAPs since the 1980s, empirical evaluations of their real-world impacts are scarce, as the majority of the existing literature is qualitative. Although qualitative approaches provide valuable contextual insights and help to challenge RNPs’ effectiveness in achieving their intended outcomes in DCs, they leave a critical gap in quantitatively assessing how these policies have impacted these economies in meeting—or failing to meet—their stated objectives. In fact, without empirical confirmation, development narratives risk becoming entirely ideological. This study attempts to fill this gap in the literature. The findings of this study will amplify marginalized perspectives, empower civil society, scholars, and activists to hold international corporate capital (ICC) accountable, support calls for the re-nationalization of essential services, expose the human costs of RNPs, and promote alternative development pathways grounded in equity, sustainability, and inclusion.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 examines the relevant empirical literature.

Section 3 describes the approach used to test the study’s hypotheses.

Section 4 discusses the findings, and

Section 5 concludes the research and provides policy implications.

2. Literature Review

The qualitative response of the subset of the RNPs on the indicators of development and underdevelopment in Africa has been debated extensively. The main purpose of these debates was to establish how the RNPs respond to these countries’ development or under-development. This section focuses on the studies that are most relevant to this study. Selected studies are organized as follows:

Using a qualitative approach, focusing on secondary data analysis which includes academic literature, reports from international organizations, and case studies, John, Messina, and Odumegwu (2023) studied multifaceted impacts of neocolonialism on Africa’s economic growth and development and discuss various solutions to mitigate its negative effects. According to the findings, Africa continues to suffer from economic dependence, corruption, political interference, cultural subjugation, power imbalances and stunted development as a result of neocolonial exploitation. The study further highlighted the role of foreign aid, trade, MNCs, and IFIs in perpetuating neocolonial/neoliberal practices. These mechanisms enable former colonial powers and the USA to maintain indirect control over Africa’s economic and political landscape, impeding genuine progress. The analysis suggests that the solutions to these problems include promoting fair trade practices, empowering African states to reclaim control of their resources and economies, encouraging regional integration and collaboration, strengthening governance and institutions, and establishing a more equitable global economic system.

Kumi et al., (2014), using a methodology similar to that of John, Messina, and Odumegwu (2023) critically analyzed the relationship between the neoliberal economic agenda and sustainable development (SD) in DCs with particular emphasis on post-2015 SD Goals. They focused on the response to a subset of RNPs namely privatization, trade liberalization and reduction in government expenditure on the attainment of SD goals and their implications for the post-2015 SDGs. Their findings revealed that these tenets of neoliberalism hamper the achievement of SDGs in some contexts by increasing poverty and inequality. As a result of poverty-induced constraints, environmental resources such as forests are used more. Furthermore, the state’s regulatory ability for environmental management has been diminished, mostly due to fiscal restrictions imposed by the embrace of neoliberalism. The authors contend that recent progress in furthering SD as an ideal development aim has been jeopardized by the advent and growth of neoliberal regimes in DCs. Their results show that reliance on market mechanisms alone in the management and allocation of environmental resources is inevitably insufficient and problematic and therefore calls for a new approach. Similarly, focusing on subset of the RNPs—namely cuts in government spending, deregulation and the same methodology, Martinez, (2016) critically studied the impact of neoliberalism on various aspects of Latinos life and shows that Latino communities experienced persistent poverty, declining household incomes, and reduced wealth (or simply socioeconomic decline), criminalization, and racial discrimination. The author concludes that by prioritizing market efficiency over social equity, neoliberalism has significantly hindered the advancement of Latino communities in the U.S.

Obeng Odoom (2012) using similar methodology, critically scrutinized the effcts of the neoliberal economic reforms on urban employment, inequality, and poverty in Ghana and found mixed evidence. Specifically, the study found that while RNPs have led to increased private sector involvement in urban economies, resulting in capital formation and job creation, they have also significantly increased inequality, exacerbated poverty and urban challenges. The study recommends policy interventions to tackle these issues.

Using a qualitative and cross-country comparative approach, Castro (2008) examined the impact of RNPs promoting private sector participation—focusing only on both water and sanitation services, or simply privatization, as one of the key tenets of the neoliberal project—in nine DCs across Africa, Latin America, and Europe. The study reveals that the RNPs’ emphasis on privatization in water and sanitation services leads to increased inequality as privatization has resulted in high tariffs and thus reduced access for low-income population (majority in these countries) and financial shortcomings, as the private sector has not consistently brought the expected financial resources. The study also highlights regional disparities, as foreign private capital inflows have been unevenly distributed, thereby worsening regional inequalities. The study concludes that relying on the private sector to achieve water and sanitation development goals is misguided in poor countries. It advocates for more inclusive approaches that combine both public and private efforts to achieve this goal.

In his study, Kihika (2009) examines the impact of NGOs under the influence of neoliberal policies on promoting development in sub-Saharan Africa and concludes that development agencies create strong dependence on external markets—which benefits capitalist expansion and the conquest of new markets—and on donor funding, both of which undermine the foundations of development in these countries.

Also using a qualitative method, Hill and Kumar (2012) examined the influence of neoliberalism on education and concluded that neoliberal policies, both in the UK and globally, have resulted in (i) a loss of equity, and economic and social justice within the education system; (ii) a loss of democracy and democratic accountability in educational institutions; and (iii) a loss of critical thinking in the education system.

To summarize, the material discussed above is mostly qualitative in nature. However, from an empiricist perspective, arguments that are not based on empirical data may be dismissed as mere speculation, contributing neither to true theory confirmation nor having objective scientific weight (Andersson, 2012). This study aims to fill a vacuum in the literature by providing empirical evidence on how African economies respond to RNPs. We argue that the central tenets of RNPs—price stability, fiscal discipline, liberalization of inward FDI, privatization of public enterprises, corporate tax cuts, interest rate management, competitive exchange rates, free trade, economic deregulation, and property rights protection—have had a significant impact on African countries’ overall economic performance over the last three decades. These policy features have been continually advanced via successive neoliberal reforms, ranging from structural adjustment programs (SAPs) to the ongoing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Unit Root Tests

To check the variables unit root, we used the Im-Pesaran-Shin test.

Table 2 presents the results. These results indicate that only GNL, GDPPCP, GCFGDP, FDIGDP, INFL, and OEXR are stationary at level, whereas other variables such as HDI, GEXP, CTR, PIDGP, PIDGP, and TO became stationary after being transformed into their first differences (I(1)).

4.2. Lag Order Selection Criterion

After conducting the unit-root tests, the lag length of the VECM is determined. We use vector auto-regression (VAR) lag order selection criterion to identify the optimal lag length for the co-integration test.

Table 3 presents the VAR log order selection criterion. According to this table, the optimal lag recommended by SC criterion is lag 2.

4.3. Co-Integration Test

With the maximum lag length of 2 (

Table 3), a Johansen cointegration test was performed, and the results are shown in

Table 4. The trace test results rejected the null hypothesis of no cointegrating vectors at the 5% level of significance. Thus, these findings confirm the presence of 8 co-integrating equations at the 5% level of significance.

4.4. Responses of African Economies to RNPs

The estimated responses of FCF, as a proxy for development indicator in Africa, to neoliberal policies are presented in Eq.3. The estimated coefficients match theoretical literature predictions. To begin with, the long-run coefficient for INFL targeting policy, which serves as a proxy for pricing stability, is negative (-0.24) and statistically significant, suggesting that efforts to achieve low and stable inflation rates—through inflation targeting—have a negative impact on GFCF in the sample countries. This implies that inflation targeting such as labor market reforms to encourage flexibility and lower employment costs, as well as enforcing money supply objectives to maintain fiscal discipline and anchor private sector expectations, have discouraged capital formation in Africa. This is consistent with Ogbonna’s (2012) observation that neoliberal policy is inherently inflationary because it raises the amount of domestic currency required in exchange for a unit quantity of local goods and imports (Monbiot, 2016) by emphasizing investing little and charging much. Thus, this result provides an argument against inflation targeting, for we have found that it harms these countries.

The coefficient of government borrowing to finance deficits —used as a proxy for fiscal discipline, and representing a key element of neoliberal policy over the study period, is negative (-0.632) and statistically significant at 10% level. This implies that, in the countries under investigation, efforts to finance government budget deficits through both internal and external borrowing are associated with reduction in the gross fixed capital formation as the RNPs prioritize debt repayment over productive spending. This suggests the presence of both debt overhang and crowding-out effects in the study countries. These findings are consistent with those of Dawood, Feng, Ilyas, & Abbas, (2024) who found that external debt and debt servicing have indirect negative effects on the economies of developing countries.

The crowding-out effect, debt overhang and external debt servicing may be the mechanisms by which this negative relationship occurs. This aligns with the findings of Abdullahi, Bakar, and Hassan (2016), who argue that debt, particularly external debt, is a necessary evil that all economies must contend with. These authors, specifically, attribute the negative outcomes to debt overhang and crowding out effects, which have hindered economic development (Abdullahi, Bakar, and Hassan, 2016). Naiman and Watkins (1999) take a similar stance, noting that poor countries continue to divert resources away from health care, infrastructure, and education in order to service external debt. In doing so, they displace vital private-sector investments and distort the economy through the taxation effect.

Accordingly, Yelpaala (2010) argues that RNPs, which are primarily centered on foreign development aid programs, have failed to serve as an effective tool for economic development. This is because, despite four decades of aid programs, many poor countries have stayed poor, with some becoming significantly poorer relative to their own historical standards and compared to other nations (Yelpaala, 2010). According to Bond (2008), per capita incomes in many African countries are still lower than they were during the 1950s-60s era of independence. One probable explanation for this is that aid programs or externally generated policies prioritize foreign interests over local needs in the countries involved. These initiatives and policies are designed to benefit wealthy nations, international organizations, and multinational corporations over the sovereign development of the countries they are meant to help. As a result, they worsen poverty, undermine local governments, increase dependency, and fail to solve core social and economic challenges, making it more difficult for these countries to develop sustainably and equitably.

The estimated long-run coefficient of the TO as a proxy for income convergence, which is part of the RNPs and dominant over the study period, is negative and statistically significant. This implies that transitioning from no trade or protected industries to free trade, rooted in imbalanced power dynamics, resulted in a flood of industrial surplus and capture of local markets, which destroyed the market for domestic industrial produce due to their inability to compete with giant TNCs in terms of price (Singh, 2022; Moyo, Kolisi, & Khobai, 2017, Nuruzzaman, 2004). That is, opening up to the global market causes African countries to abandon their domestic potential industries with moderate productivity and global aspirations that served as import substitutions and increase imports. Thus, the free-market economy forces these countries to specialize in being poor. This is also consistent with Castellano, Lizárraga, and Ruiz (2022), who argue that by requiring maximum external openness, the RNPs have transformed African countries into markets for MNCs.

The above is also consistent with the argument by Kumi, Arhin, and Yeboah’s (2014) who contend that the free-market system exclusively rewards the ‘strong’ while leaving the ‘weak’ far behind. This situation arose after African elites were persuaded to abandon the protectionist measures once used by the imperial powers to achieve global competitiveness, resulting in the premature demise of infant industries. Thus, liberalization measures, as suggested by the neoliberalism, are the root cause of African industry destruction and, consequently, hinder capital formation. This was accompanied by the elimination of productivity-enhancing public inputs such as food, fertilizer, education, and other agricultural inputs (Nuruzzaman 2004), increasing the burden on the common people. As a result, the food shortages have increased (Siddiqui, 2018), highlighting the inefficiency of the RNPs. Our findings support the mercantilist idea that economic activity is a zero-sum game in which one country’s economic benefit comes at the expense of another.

Our findings are also consistent with Tandon, (2015) who established that Africa’s economy is shattered – devastated – by the so-called ‘free trade’ dogma. Without the intervention of appropriate institutions that counteract the tendencies of free trade, these problems are likely to become chronic (Shaikh, 2006). The policy implication for this is that Africa must contest the concept that comparative advantage occurs naturally rather than as a product of successful and dynamic industrial and trade policies. Accordingly, effective industrial strategy to promote fair trade is necessary to shape these countries’ standing in the global trading system, as the consequences of their absence are too obvious to ignore.

The long-term coefficient of FDI (as a proxy for privatization) is positive and statistically significant, indicating that privatization of assets as a way of opening up new fields for global capital accumulation responded positively to GFCF in Africa. However, in this study, we firmly subscribe to Buckley, Leddin, and Lenihan’s (2006) and Frimpong’s (2020) assertions that the impact of FDI in host DCs can be overestimated by failing, for example, to account for the ‘decapitalization’ of the economy through profit repatriation and the use of numerous under-the-counter surplus transferring strategies such as transfer pricing. MNCs, in particular, can walk away when profits run out, leaving the general public to pick up the debris. In this way, neoliberalism nationalizes harms while privatizing the profits derived from the harms. Thus, future research on this topic should consider all of these factors in their analysis. This would, for example, put to test the claim made by Yelpaala (2010), who argues that an understanding of the system’s characteristics, strategic vision, and mission of MNEs would suggest that the developmental weight of African countries should not be shifted to MNEs as they are not well adapted to the task as direct instruments.

The estimated long-term coefficient of CO2, as a proxy for deregulation, a key component of the RNPs, is both negative and statistically significant. This implies that free-market reforms, which were aimed at improving environmental quality in these countries by eliminating subsidies claimed to encourage over-exploitation of land and excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides, have instead exacerbated the environmental crisis, which is critical to these countries’ long-term development. The possible explanation for this s that the abrupt removal of subsidies without alternatives, farmers, especially, smallholder farmers may struggle to maintain productivity, resulting in lower agricultural output, land degradation, and increased vulnerability to environmental shocks such as droughts. That is, small farmers may be driven to increase their use of detrimental practices, such as overworking the land or depending on cheaper, less efficient inputs, which exacerbates soil erosion and nutrient depletion. This, in turn, reduces crop yields and jeopardizes long-term food security, especially in poor countries such as those of Africa.

For example, fertilizer usage rates in these countries—particularly in SSA—remain lower than the global average, owing to the government’s elimination of productivity-enhancing agricultural inputs, as well as significant losses of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients in the soil, which exacerbate land exploitation. Furthermore Siddiqui (2022) noted that the strain placed on the land by the growing population, combined with insufficient governmental investment, may explain a range of issues, such as over-crowded agriculture, higher rents, increased farmer debt, and inadequate wages (Siddiqui, 2022). These factors favor both the use of subsidies and environmental regulation to halt this trend, lessen soil erosion, and boost yields (Porter, 2003).

The long-run estimate of the coefficient of private domestic investment as a ratio of GDP shows a negative and significant response to capital formation. The possible explanation for this is that corporate businesses may have invested more in financial assets, such as capital markets and speculative ventures, than in the real economy, which could explain why increased private domestic investment as the statistics indicate, has not led to increased physical investment. This could be explained by the real sector’s instability and capital misallocation both of which are rooted in deregulation, a key tenet of the RNPs.

The above is consistent with Akyüz, (2019), who argues that investors often prefer financial markets over productive investments in sectors like agriculture or manufacturing in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Singh and Tiwana (2020) share a similar view, claiming that deregulation resulted in a spectacular increase in finance capital, altering the nature of capital accumulation and tipping the balance in favor of financial industries. This is consistent with Tandon’s (2015) claim that money became a method to produce additional money without passing through the production phase. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in DCs, where financial markets are frequently perceived as safer or more rewarding than physical assets, resulting in a negative link between private domestic investment and capital formation. This requires effective government intervention to prevent bank credit from being diverted into unproductive and intrinsically unstable speculative activity. This is consistent with Siddiqui and Armstrong’s (2018) findings that speculative financial flows unrelated to the real economy are unproductive and should be banned.

Despite being designed to encourage private investment, the estimated long-term coefficient of CTR, which is part of neoliberal policies, is negative but statistically insignificant, implying that capital formation exhibits a neutral responsiveness to reductions in marginal corporate tax burdens. In other words, a decrease in corporate tax payments does not result in a rise in real investment. One possible explanation for corporations’ neutral response to tax cuts is that in Africa, corporations are more influenced by economic conditions that determine firm profitability, market size, availability of natural resources, and investment climate factors such as institutional quality, low corruption, and political stability (rather than tax rates). This is consistent with the findings of the Economic Policy Institute (2017) which found no substantial relationship between reduced CTRs and increased investment. More worryingly, this institute found that countries with lower corporate tax rates generally saw slower growth in capital investment. The mechanism through which this may occur is through an increased fiscal deficit, thus limiting the ability of the country in question to deliver adequate public amenities.

The estimated long-term RIR coefficient, which is relatively high in Africa, is positive and statistically significant. Specifically, our findings demonstrate that a one percent rise in ln_RIR results in a 2.91 percent increase in capital formation, all else being equal. This indicates that investment and business commitment respond to positive changes in lending interest rates by rapidly expanding capital flows in these nations, as local banks may borrow a large amount of foreign capital. Thus, the availability of capital is what matters. This suggests that financial liberalization stimulates increased capital inflows, a greater share of which is channeled into the real sector of the economy. This finding is in line with Adabor, (2022) who posits when lending rates are high, they attract riskier projects and fewer borrowers (consumers) which in turn affect more real sector of the economy.

The estimated long-term coefficient of OEXR is negative and highly statistically significant, indicating that exchange rate depreciation harms capital formation in African countries. Specifically, if the exchange rate rises by one percent, capital formation will fall by about 0.04%, with all other factors staying unchanged. One probable explanation is that devaluation in these countries typically occurs when the primary objective is to increase subsistence in the short run rather than to expand exports, which is the primary motive for devaluation. Thus, calling for devaluation is not recommended if the primary objective is to increase short-term sustenance. This is consistent with Mishkin, F. S. (2018) who evidenced that exchange rate depreciation DCs tends to lead to inflationary shocks, which reduce the confidence of investors in the long-term economic stability of the country.

In line with the above, economic literature recommends that the government direct its exchange rate management policy towards appreciation of exchange rate in order to reduce production costs in the manufacturing sector, which is heavily reliant on foreign inputs, while restricting imports of domestically produced consumer goods. The bigger the volume of foreign inputs, the higher the cost, which discourages industrialization. This means that currency devaluations intended to boost exports have instead resulted in an import crisis, exacerbating Africa’s technological underdevelopment and deindustrialization. Furthermore, devaluation raises the debt load of both the private and public sectors, resulting in a loss in net asset value. According to Acar (2000), the LDC governments should avoid using a flexible exchange rate system that allows for large depreciation as it can hinder economic development.

The estimated long-term coefficient of government spending, serving as a proxy for the size of state activities, is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that African governments that prioritizing market promotion as a means of allocation have a negative impact capital formation. This outcome can be attributed to two factors: (1) emphasis on spending cuts and (2) reordering public expenditure priorities. Regarding expenditure cuts, governments of these countries have implemented reductions in public support for infrastructure, education, social services and research and development.

Regarding the reordering public expenditure priorities, these countries have shifted from productive investments towards debt serving, reflecting a focus on market discipline. All of these have led to a constrained fiscal environment, limiting the resources available for investment in critical sectors and hindering capital formation. This is consistent with However,

Stiglitz (2013) who argues that focusing exclusively on fiscal discipline (spending cuts and reordering public expenditure priorities) without ensuring adequate funding for development programs can severely undermine efforts to foster capital formation in developing economies. Instead of austerity and reordering public expenditure priorities, we suggest that poor nations should prioritize enhancing the quality of public spending, boosting investments in human and physical capital, and creating an environment that encourages private investment.

Overall, the parameter estimates from Equation 3 are significantly different from zero, and overridingly negative. This suggests that African economies have exhibited a strong negative response to RNPs. This finding aligns with the findings of SA’ADU (2023), who evidenced that that neoliberal development initiatives have consistently failed Africa in resolving its development challenges. These results also support the critiques raised in the study’s introduction, which contend that neoliberal policies are fundamentally self-serving—designed more to benefit ICC in particular and imperial countries in general than the countries they target.

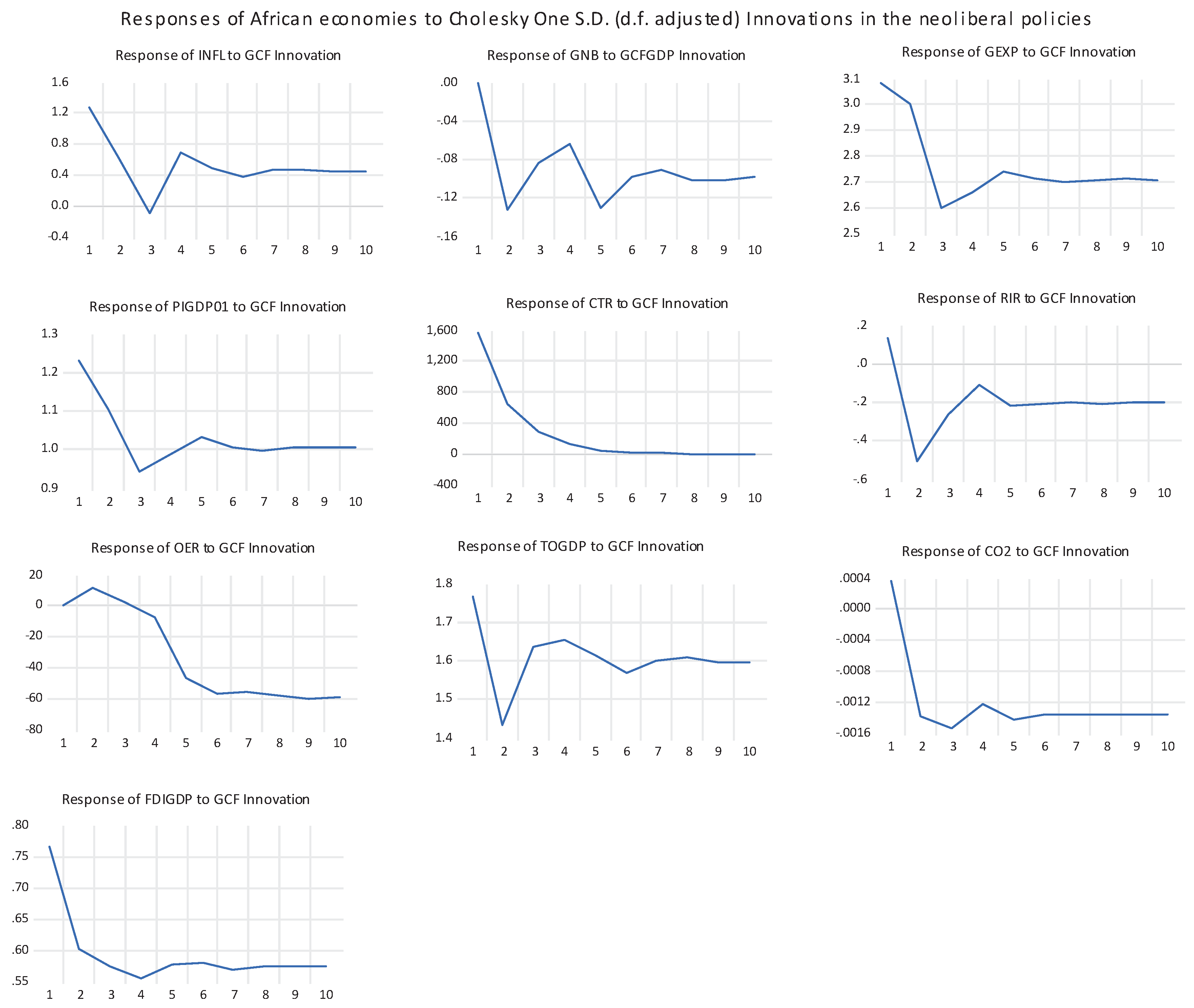

4.5. Impulse Response Function (IRF)

The IRF results show that capital formation responds negatively to inflation targeting, government net borrowing, government expenditure, government investment, corporate tax rate cuts, the official exchange rate, trade openness, and fossil carbon dioxide, but positively to real interest rates and FDI in the study area. These findings support those from the baseline model (Eq. 3).

Figure 1.

Estimates of the IRF.

Figure 1.

Estimates of the IRF.

4.6. Robust Check Results

To assess its robustness, we replaced GFC with various development indicators including HDI, GDPPC, and GDP growth rate, and the results are shown in Eqs. 4, 5, and 6 in the Appendix as alternative estimates. As shown in these equations, the results were all qualitatively similar to those from the baseline model. As a result, we can be confident that our baseline findings are robust.

5. Conclusion

RNPs were imposed on debt-stricken African countries as a response to imperial power’s corporate profitability crisis, which triggered a fall in demand for commodity exports. This led to a reduction in government income, thereby exacerbating the debt crisis. The result was the emergence of a new paradigm of capitalism (neoliberalism), which sought to reverse the crisis and save capitalism from itself at the expense of peripheral nations. This occurred by integrating periphery economies into a unified global market, giving core multinational institutions more control over periphery markets, resources, and policies. Using the available data, this study examines how African economies have responded to these externally imposed RNPs. To do so, we relied on a restricted Vector Autoregressive model (VAR), also known as the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM), and a panel data set from 29 African nations spanning 1980 to 2022.

The empirical findings reveal that implementing RNPs in African countries fulfills only two promises: higher real interest rates and increased FDI inflows. Both contribute to capital inflows into these capital-scarce economies, which respond positively through increased capital formation. The empirical study, on the other hand, identified several areas where the implementation of RNPs did not result in the expected changes, but instead aggravated and prolonged the very developmental challenges they were ostensibly designed to resolve. These include drastic cuts and reordering of public and social spending, which occurred alongside rising food insecurity and a balance of payments crisis, among other things; trade liberalization, which has led to premature deindustrialization and locked African economies into unequal exchange relationships; deregulation, which has undermined the capacity of African states to adequately respond to the devastation caused by unregulated economic agents, effectively turning.

Furthermore, exchange rate depreciation has a contractionary effect in these countries, both in the short and long term. These findings show the RNPs’ duplicity, as they promise development while reinforcing development issues. In reality, market systems require the participation and assistance of national governments. Overall, the model’s aggregated parameter values depart from zero but stay smaller than zero. This demonstrates the profoundly damaging impact of the neoliberal radical reform program. Instead of addressing underdevelopment, RNPs have exacerbated it. Evidence of this failure can alter reformers’ abstract ideas, leading to more effective steps to prevent negative consequences.

Specifically, we conclude that competitive exchange rates, trade openness, capital flow liberalization, and corporate tax cuts are ineffective policy instruments for managing African economies’ external sector, as they have driven these countries to specialize in low-value-added activities that exacerbate poverty. Similarly, government spending cuts, fiscal discipline measures, and deregulation are insufficient for managing internal economic affairs, resulting in increased food insecurity, unchecked external exploitation of local resources, social marginalization, and the growing influence and control of core international institutions. Understanding these fundamental concerns is crucial, as African countries’ long-term economic performance will be determined by how effectively they address these challenges. Addressing them will necessitate a concerted combination of domestic policy reform and global structural transformation.

To strengthen their standing in the global trade system, African economies must adopt national strategies that are more in line with their stage of development and specific conditions, while simultaneously encouraging the creation of high-tech and high-value-added products. Those countries with significant natural resources, in particular, must capitalize on them through local processing as a foundation for economic transformation, growth, job creation, and industrialization, which is key steps toward addressing Africa’s marginalization and specialization in being poor.

It should be underlined that decreasing trade barriers with Africa will be ineffective until the current dominating paradigm shifts away from primary exports and towards high-value manufactured commodities. To accomplish this effectively, agricultural policy must prioritize boosting domestic food supply and decreasing reliance on imports—particularly for basic necessities—in order to limit wages, and hence industrial production costs, from rising.

African countries should prioritize increasing the productivity of public inputs such as food subsidies, targeted education, infrastructure, technology acquisition and innovation, and other measures that assure food security and assist prevent balance-of-payments problems. Once these foundations are in place, the exchange rate depreciation can better achieve its intended purpose of increasing exports.

Furthermore, measures to re-empower citizens and communities to take responsibility for their own development must be prioritized if Africa is to accomplish significant transformation. This can be accomplished by replacing top-down, externally imposed development models with locally driven, participative, and accountable methods. Similarly, targeted foreign direct investment (FDI) in specific industries or regions matched with a host country’s long-term development goals, aspirations, and local conditions is critical for industrial development. More crucially, genuine formal regional cooperation among member nations, based on improved mutual trust and interchange, is critical not just for Africa’s industrialization but also for increasing its negotiating power in the World Trade Organization.

Instead of negotiating separately, African nations should band together under a unified voice and representation to oppose global trade policies that harm their own development. In particular, there should be a substantial revision to the conditions of bilateral and multilateral financial aid to African nations, including those pertaining to currency depreciation, free trade, and tax cuts for multinational corporations (MNCs). WTO regulations must be drastically amended to allow African nations to more effectively undertake industrial policies that address underdevelopment. Allowing African countries to adopt policies that are more appropriate for their developmental phases and the numerous constraints they encounter will allow them to grow faster.