Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

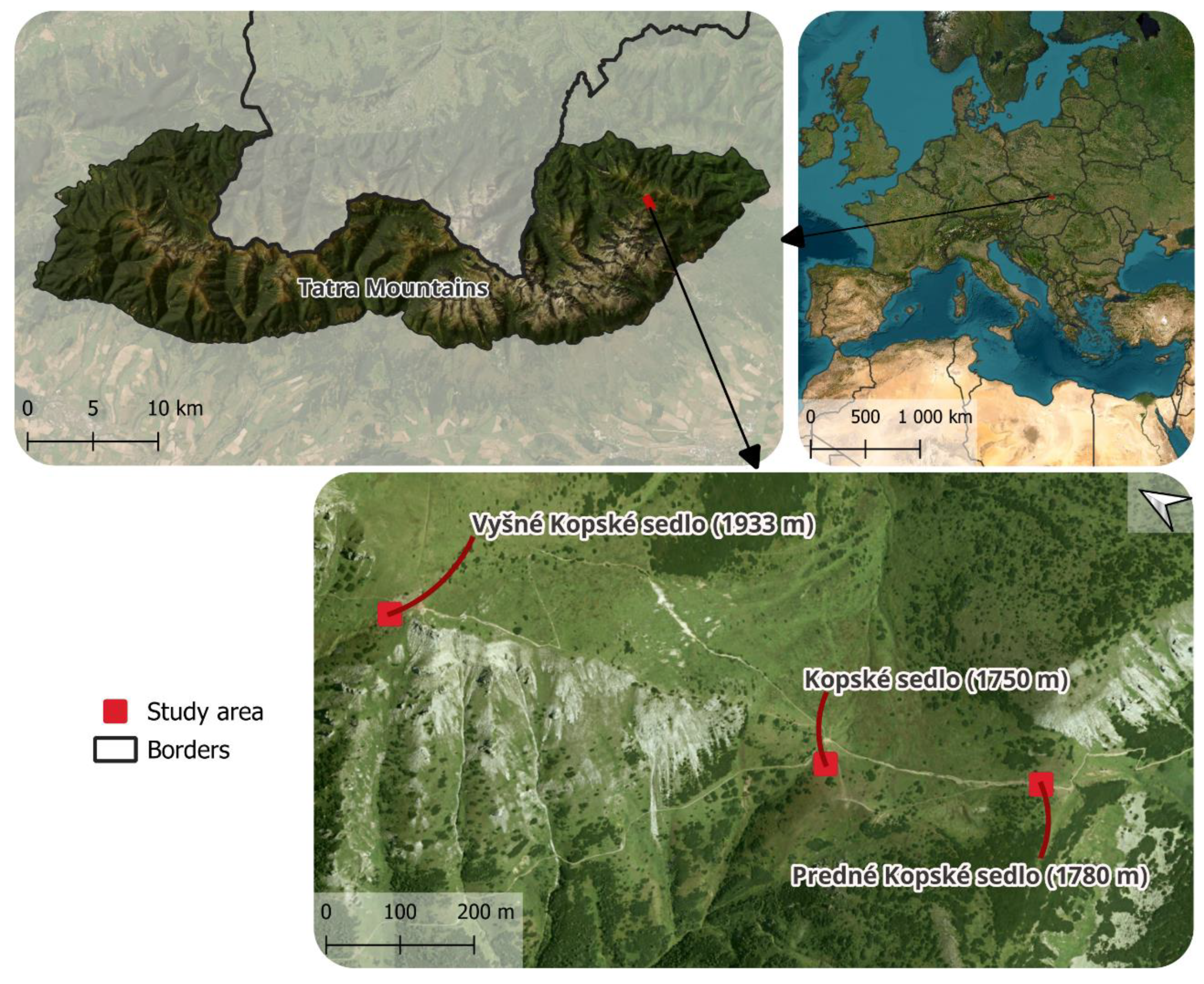

2.1. Study Area

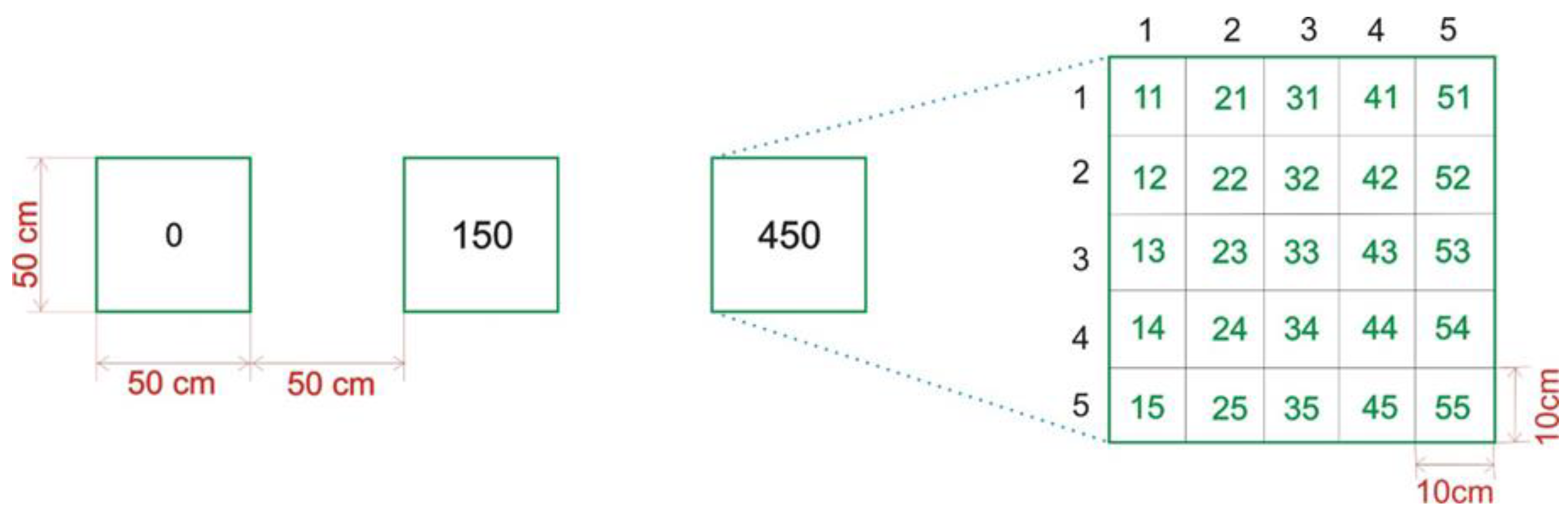

2.2. Experimental Block Design

- Cover (%) of vascular plant species (E1 layer), mosses and lichens (E0 layer). Only green photosynthetic material should be included in the cover estimates (visual estimates of the highest cover perpendicular to each subplot; and visual estimates of the cover of each species). Lichens and mosses should be determined by a lichenologist and bryologist.

- Bare ground cover (%) (bare ground can be either mineral or soil (visual estimates of the top cover of bare ground perpendicular to each subplot; and visual estimates of the ground cover of the surface).

- Litter cover (%) (including litter from recently trampled plants (visual estimates of the top litter cover perpendicular to each subplot; and visual estimates of litter cover per subplot).

3. Results

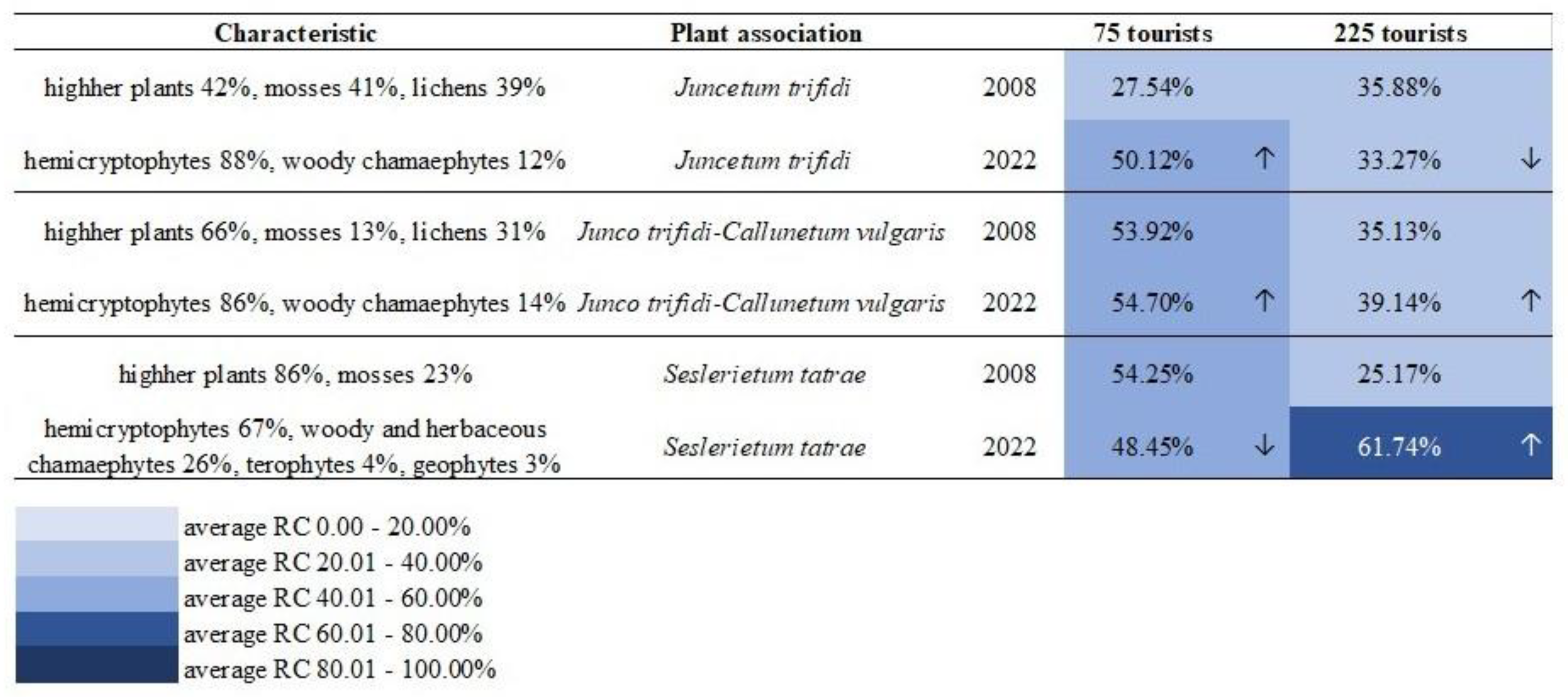

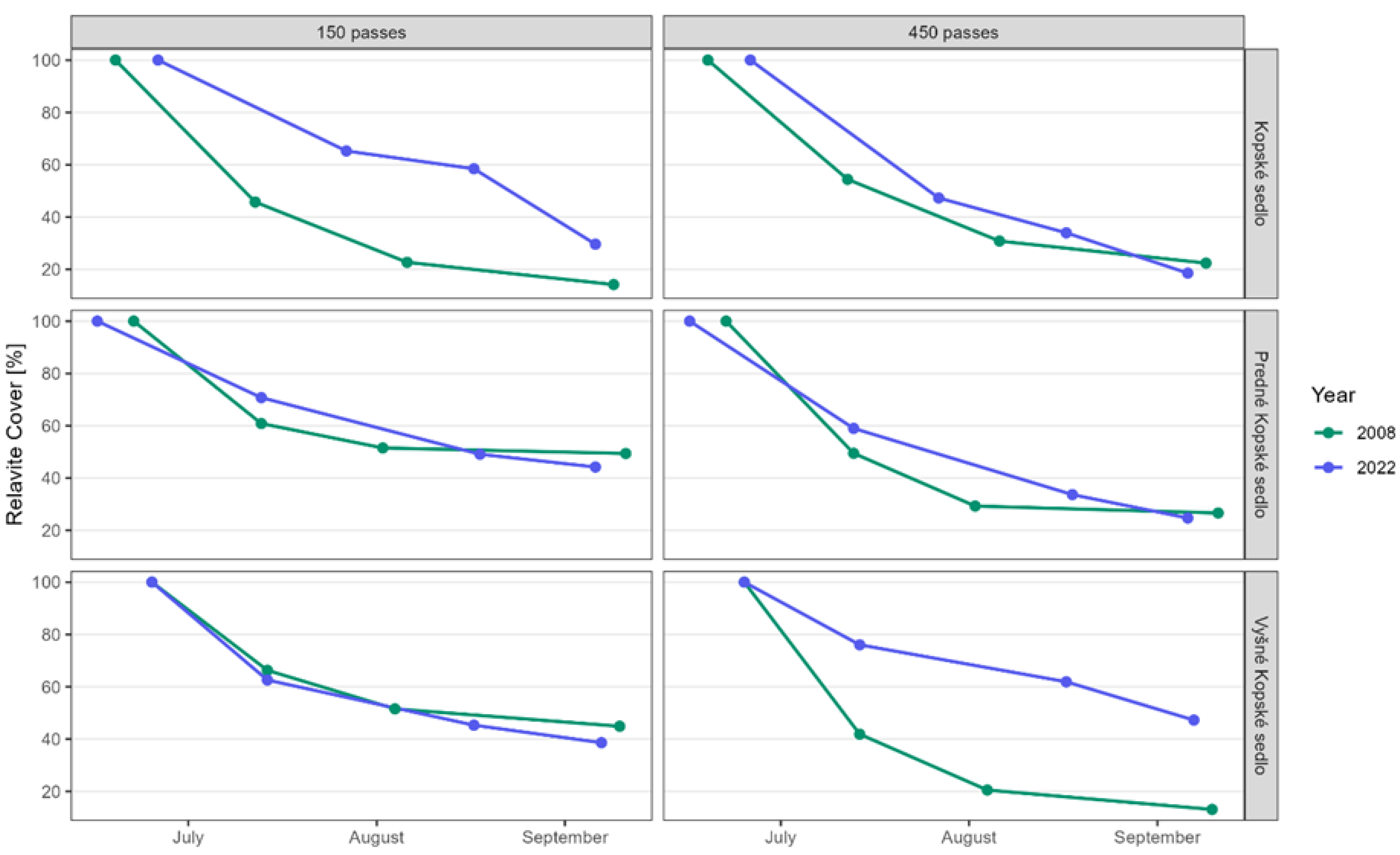

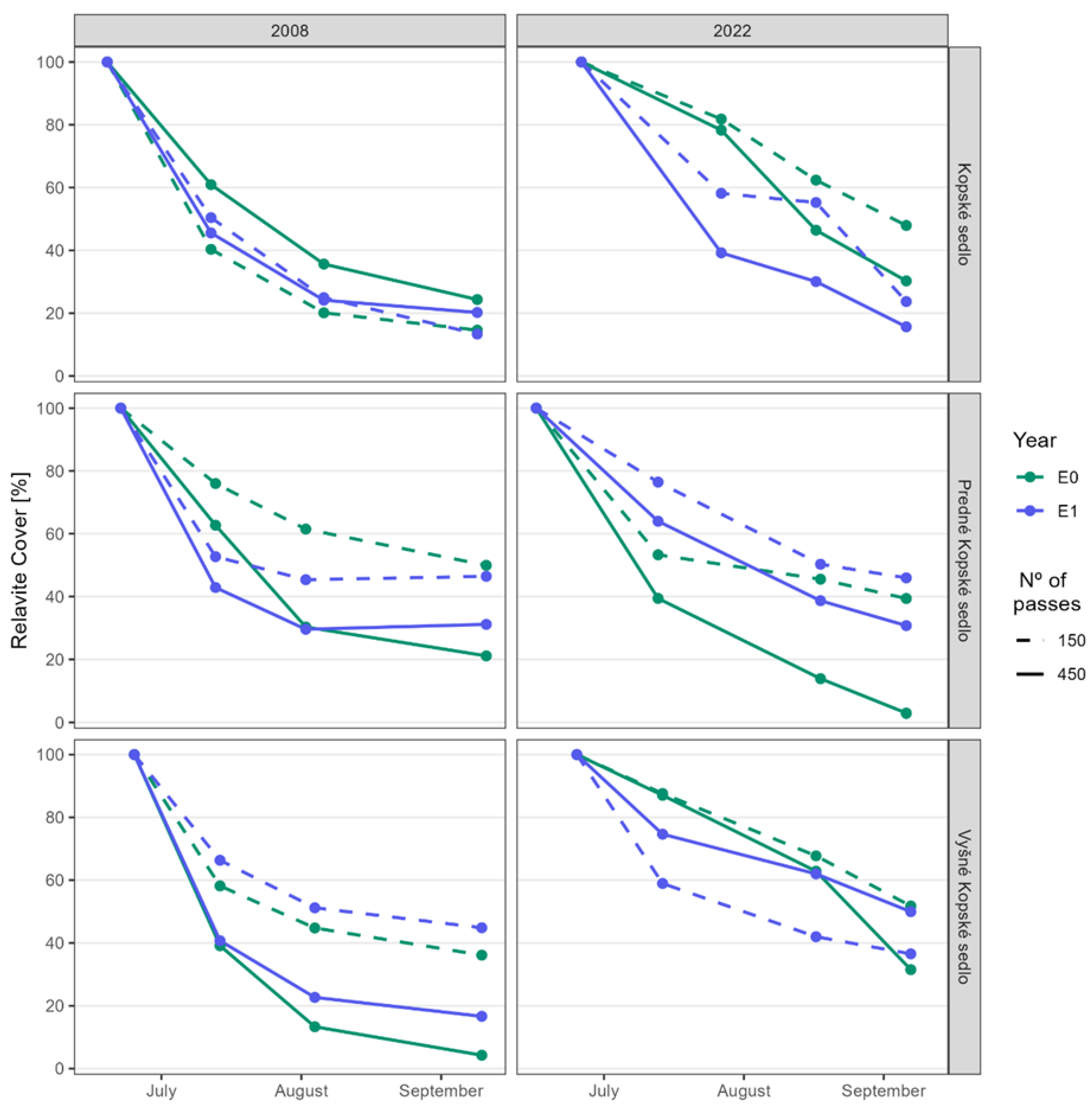

3.1. Hypothesis 1: Regenerated Plant Communities Are More Resistant to Trampling Than Native Ones

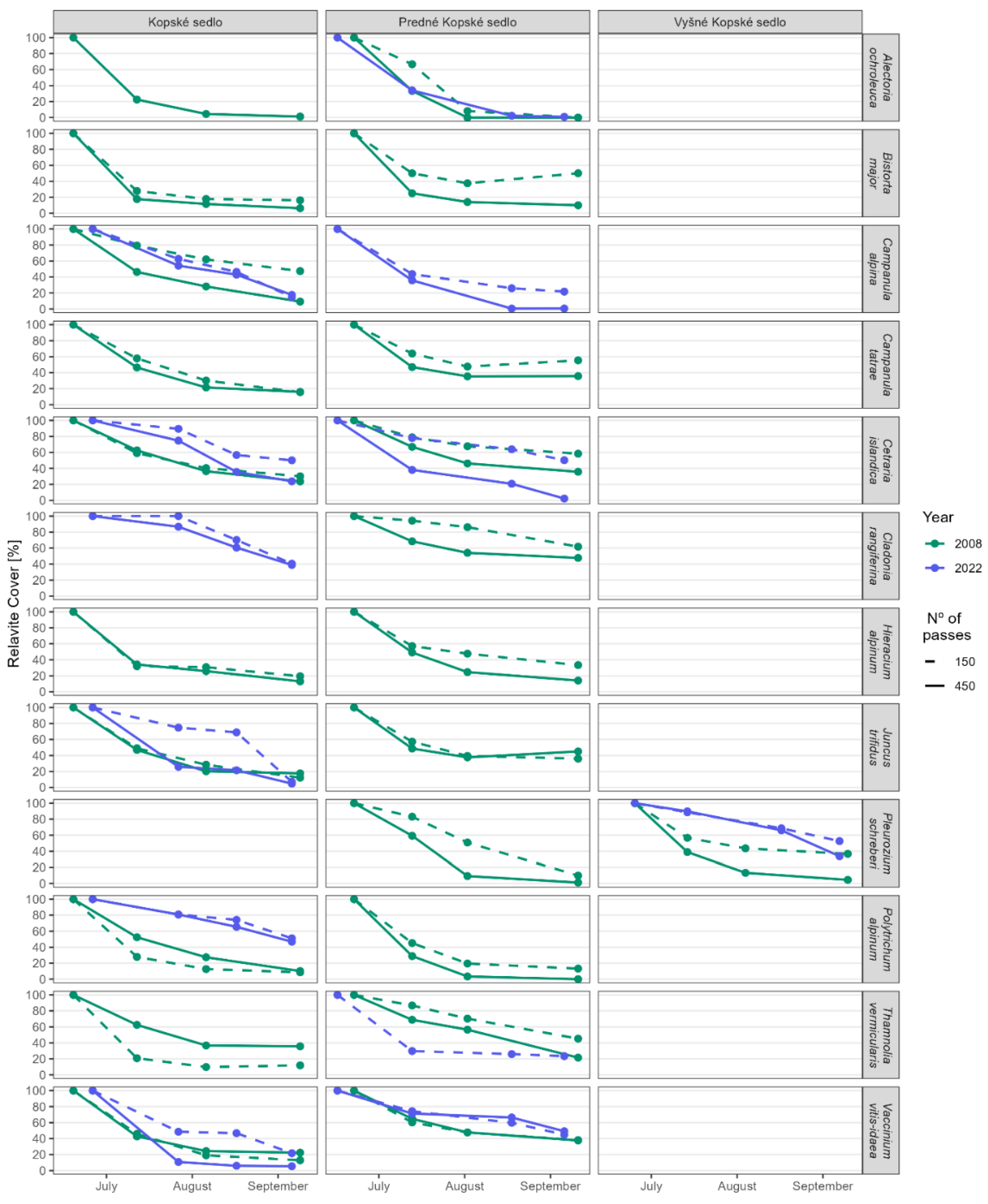

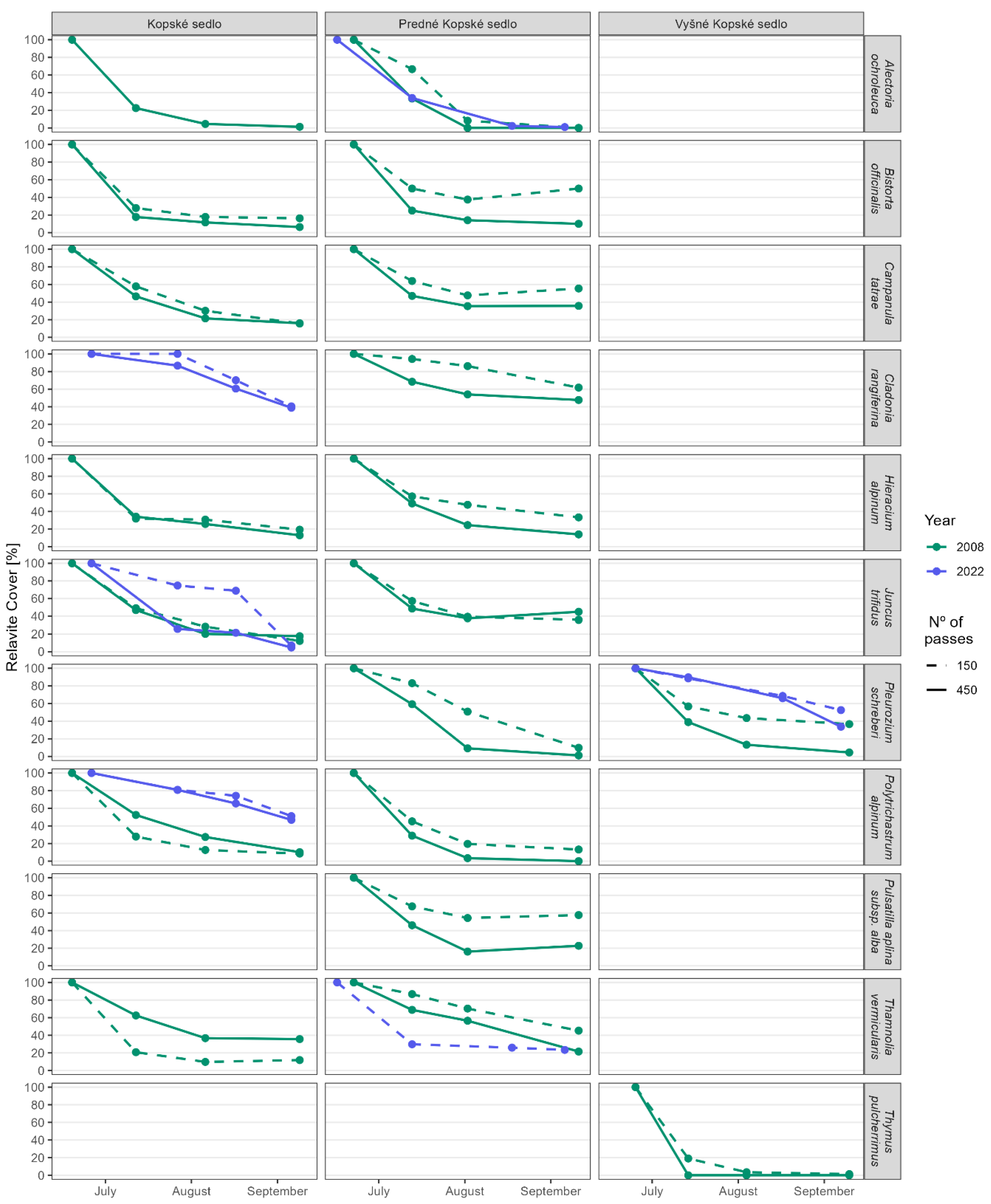

3.2. Hypothesis 2: Do Individual Species Found in Different Communities Defend Themselves with the Same Resistance to Trampling?

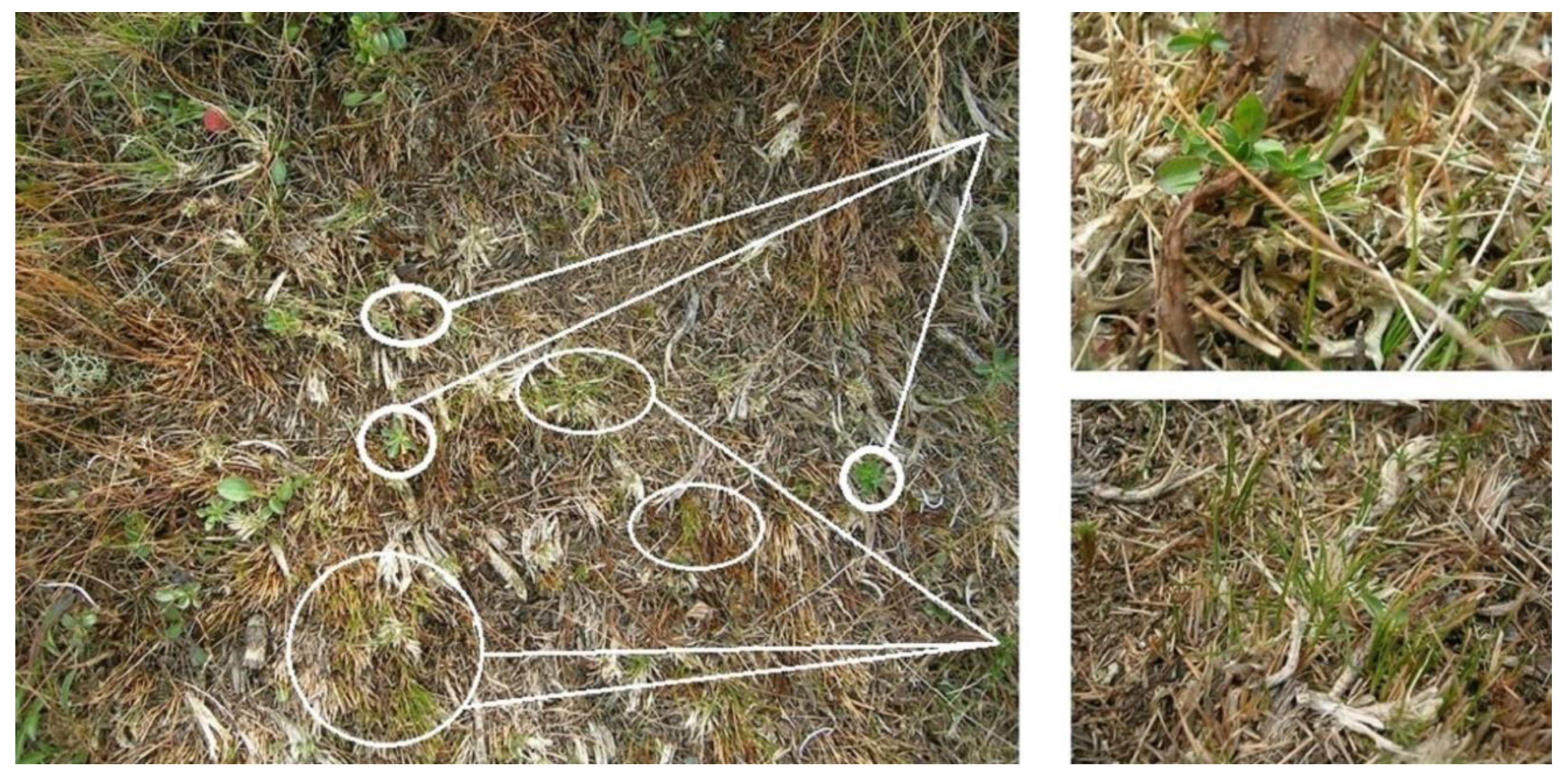

3.3. Hypothesis 3: Can Trampling Cause Species Extinction?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPP | National Nature Preserve |

| RC | Relative Cover |

References

- Li, Y., Chen, K., Liu, Z., Cao, G. Short-term impacts of trampling on selected soil and vegetation properties of alpine grassland in Qilian Mountain National Park, China. Global Ecology and Conservation, 2022, 36, e02148. [CrossRef]

- Hill, W., Pickering, C. M. Vegetation associated with different walking track types in the Kosciuszko alpine area, Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 2006, 78, 24–34.

- Growcock, A. J. Impacts of camping and trampling on Australian Alpine and Subalpine vegetation, 2005. Doctoral dissertation, PhD Thesis. Gold Coast, Australia: Griffith University.

- Pickering, C. M., Growcock, A. J. Impacts of experimental trampling on tall alpine herbfields and subalpine grasslands in the Australian Alps. Journal of Environmental Management, 2009, 91, 532–540.

- Li, Z., Siemann, E., Deng, B., Wang, S., Zhang, L. Soil microbial community responses to soil chemistry modifications in alpine meadows following human trampling. Catena, 2020, 194, Article 104717.

- Kozlowski, T. T. Soil compaction and growth of woody plants. Scandinavia. Journal of Forest Research, 1999, 14, 596–619.

- Yüksek, Y. Effect of visitor activities on surface soil environmental conditions and aboveground herbaceous biomass in Ayder natural park. Clean Soil Air Water, 2009, 37, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, J. L., Cole, D.N. Spatial and temporal variation in soil and vegetation impacts on campsites. Journal of Applied Ecology, 1996, 6, 520–530. [CrossRef]

- M. Rutherford, J. M., Arocena, S. K., Nepal, M. Rutherford Visitor-induced changes in the chemical composition of soils in backcountry areas of Mt Robson Provincial Park, British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Environmental Management 2006, 79, 10–19.

- Meinecke, E. P. A Report on the Effect of Excessive Tourist Travel on the California Redwood Parks; California State Printing Office: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, G. H. The vegetation of footpaths, sidewalks, cart-tracks and gateways. Journal of Ecology, 1935, 23, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutiel, P., Zhevelev, Y. Recreational use impact on soil and vegetation at picnic sites in Aleppo pine forests on Mount Carmel, Israel. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, 2001, 49, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Roovers, P. Roovers, P., Verheyen, K., Hermy, M., Gulinck, H. Experimental trampling and vegetation recovery in some forest and heathland communities. Applied Vegetation Science, 2004, 7, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Speight, M. C. Outdoor Recreation and Its Ecological Effects: A Bibliography and Review; University College: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, D. , Weaver, T. Trampling effects on vegetation of the trail corridors of north Rocky Mountain forests. Journal of Applied Ecology, 1974, 11, 767–772. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. N. Minimizing conflict between recreation and nature conservation. In Ecology of Greenways: Design and Function of Linear Conservation Areas; Smith, D.S., Hellmund, P.C., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk, A. M. , Ewertowski, M. Quantifying short-term surface changes on recreational trails: The use of topographic surveys and ‘digital elevation models of differences’ (DODs). Geomorphology, 2013a, 183, 58–72.

- Tomczyk, A. M. , Ewertowski, M. Planning of recreational trails in protected areas: Application of regression tree analysis and geographic information systems. Applied Geography, 2013b, 40, 129–139.

- Komarkova, V. Alpine vegetation of the Indian Peaks area, Front Range, Colorado Rocky Mountains. Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Colorado, 1976, 655 pp.

- Zachar, D. Soil Erosion; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Fidelus, J. Slope transformations within tourist footpaths in the northern and southern parts of the Western Tatra Mountains (Poland, Slovakia). Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie, 2016, 60, 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Klug, B., Scharfetter-Lehrl, G., Scharfetter, E. Effects of trampling on vegetation above the timberline in the eastern Alps, Austria. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 2002, 34, 377–388.

- Hill, R. Hill, R., Pickering, C. M. Differences in resistance of three subtropical vegetation types to experimental trampling. Journal of Environmental Management, 2009, 90, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. N. Impacts of hiking and camping on soils and vegetation: A review. In Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism: Ecotourism Series; Buckley, R., Ed.; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pescott, O. L., Stewart, G.vB. Assessing the impact of human trampling on vegetation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental evidence. PeerJ, 2014, 2, e360.

- Cole, D. N.; Bayfield, N. G. Recreational trampling of vegetation: Standard experimental procedures. Biological Conservation, 1993, 63, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kycko, M., Zagajewski, B., Lavender, S., Romanowska, E., Zwijacz-Kozica, M. The impact of tourist traffic on the condition and cell structures of alpine swards. Remote Sensing, 2018, 10, 220.

- Hertlová, B., Popelka, O., Zeidler, M., Banaš, M. Alpine plant communities responses to simulated mechanical disturbances of tourism, case study from the High Sudetes Mts. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Landscape Management, 2016, 7, 16–21.

- Willard, B. E., Cooper, D. J., Forbes, B. C. Natural regeneration of alpine tundra vegetation after human trampling: A 42-year data set from Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, USA. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 2007, 39, 177–183.

- Chardon, N. I., Rixen, C., Wipf, S., Doak, D. F. Human trampling disturbance exerts different ecological effects at contrasting elevational range limits. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2019, 56, 1389–1399.

- Piscová, V., Ševčík, M., Hreško, J., Petrovič, F. Effects of a Short-Term Trampling Experiment on Alpine Vegetation in the Tatras, Slovakia. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 2750. [CrossRef]

- Piscová, V. Changes in the vegetation of the Tatras at selected locations influenced by humans. Bratislava, VEDA, Slovak Academy of Sciences, 2011. 300 pp. ISBN 978-80-224-1220-9.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- ent, M. Vegetation description and data analysis: a practical approach. 2nd edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 428. 2012, Available at http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0471490938 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Cole, D. N. Cole, D. N. Experimental trampling of vegetation. II. Predictors of resistance and resilience. Journal of Applied Ecology, 1995, 32, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. N. Trampling disturbance of high-elevation vegetation, Wind river mountains, Wyoming, USA. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 2002, 34, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F. S., Chapin, M. C. 1980: Revegetation of an arctic disturbed site by native tundra species. Journal of Applied Ecology, 1980, 17, 449–456.

- Karlsson, P. S. In situ photosynthetic performance of four coexsisting dwarf shrubs in relation to light in a subarctic woodland. Functional Ecology, 1989, 3, 485–487. [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen, E. M. Kokeellisen virkistyskäytön kasvillisuusvaikutukset Oulangan kansallispuistossa. M.Sc. thesis, Department of Biology, University of Oulu, 2003.

- Jahns, H. M. Sanikkaiset, sammalet ja jäkälät. Otava, Helsinki, 1996.

- Törn, A., Rautio, J., Norokorpi, Y., Tolvanen, A. Revegetation after shortterm trampling a subalpine heath vegetation. Annales Botanici Fennici. 2006, 43, 129–138.

- Callaghan, T. V. , Emanuelsson, U. Population structure and processes of tundra plants and vegetation. In. White, J. (ed.), The population stucture of vegetation, 1985, 399–439. Junk, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Ukkola, R. Trampling tolerance of plants and ground cover in Finnish Lapland, with an example from the Pyhätunturi National Park. In: Heikkinen, H., Obrebska- Starkel, B., Tuhkanen, S. (eds.), Environmental aspects of the timberline in Finland and in the Polish Carpathians, 1995, 91–110. Uniwersytet Jagiellonski, Kraków, Poland.

- Rydgren, K., Økland, R. H., Økland, T. Population biology of the clonal moss Hylocomium splendens in Norwegian boreal spruce forests. IV. Effects of experimental fine-scale disturbance. Oikos, 1998, 82, 5–19.

- Liddle, M. J. A theoretical relationship between the primary productivity of vegetation and its ability to tolerate trampling. Biological Conservation, 1975, 8, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).