Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

05 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How does human trampling disturbance affect alpine plant communities and proxy traits for plant growth and reproduction, and does this effect vary with elevation?

- Which plant species and functional types (evergreen shrubs, deciduous shrubs, sedges) are most sensitive to human trampling disturbance?

2. Results

3. Discussion

Species-Specific Responses

No effect of Elevation on Species Traits

Future Research

Implications for Trail Planning

Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

Study Site

Data Collection

Data Processing

Data Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Billings, W.D. Arctic and Alpine Vegetations: Similarities, Differences, and Susceptibility to Disturbance. BioScience 1973, 23, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, B.E.; Cooper, D.J.; Forbes, B.C. Natural Regeneration of Alpine Tundra Vegetation after Human Trampling: A 42-Year Data Set from Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, U.S.A. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2007, 39, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P. Vegetation Classification by Reference to Strategies. Nature 1974, 250, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N.; Intermountain Research Station (Ogden, U. Trampling Effects on Mountain Vegetation in Washington, Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina; U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Crisfield, V.E.; Macdonald, S.E.; Gould, A.J. Effects of Recreational Traffic on Alpine Plant Communities in the Northern Canadian Rockies. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2012, 44, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gouvenain, R.C. Indirect Impacts of Soil Trampling on Tree Growth and Plant Succession in the North Cascade Mountains of Washington. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 75, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.M.; Hill, W.; Newsome, D.; Leung, Y.-F. Comparing Hiking, Mountain Biking and Horse Riding Impacts on Vegetation and Soils in Australia and the United States of America. J. Environ. Manage. 2010, 91, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, M. Functional Diversity Outperforms Taxonomic Diversity in Revealing Short-Term Trampling Effects. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Pickering, C.M. Impacts of Experimental Trampling by Hikers and Pack Animals on a High-Altitude Alpine Sedge Meadow in the Andes. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2015, 8, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, V.K.; Kuniyal, C.P.; Nautiyal, B.P.; Prasad, P. Integrated Analysis of the Trees and Associated Under-Canopy Species in a Subalpine Forest of Western Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.M.; Hill, W. Impacts of Recreation and Tourism on Plant Biodiversity and Vegetation in Protected Areas in Australia. J. Environ. Manage. 2007, 85, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Parolo, G.; Ulian, T. Human Trampling as a Threat Factor for the Conservation of Peripheral Plant Populations. Plant Biosyst. - Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2009, 143, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, M.; Pickering, C.M.; McDougall, K.L.; Wright, G.T. Sustained Impacts of a Hiking Trail on Changing Windswept Feldmark Vegetation in the Australian Alps. Aust. J. Bot. 2014, 62, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Gonnet, J.; Pickering, C. Impacts of Informal Trails on Vegetation and Soils in the Highest Protected Area in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 127, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägerbrand, A.K.; Alatalo, J.M. Effects of Human Trampling on Abundance and Diversity of Vascular Plants, Bryophytes and Lichens in Alpine Heath Vegetation, Northern Sweden. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hens, L.; Ou, X.; Wulf, R.D. Impacts of Recreational Trampling on Sub-Alpine Vegetation and Soils in Northwest Yunnan, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N. Experimental Trampling of Vegetation. I. Relationship Between Trampling Intensity and Vegetation Response. J. Appl. Ecol. 1995, 32, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschinski, J.; Frye, R.; Rutman, S. Demography and Population Viability of an Endangered Plant Species before and after Protection from Trampling. Demografia y Viabilidad Poblacional de Un Especie de Planta En Peligro de Extincion Antes y Despues de Protegerla Contra Pisoteo. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 11, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, C.A. Patterns of Variance in Stage-Structured Populations: Evolutionary Predictions and Ecological Implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantification of the Effects of Soil Compaction on Water Flow Using Dye Tracers and Image Analysis - Mooney - 2003 - Soil Use and Management - Wiley Online Library Available online:. Available online: https://bsssjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2003.tb00326.x (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Nie, H.; Sun, X.; Dong, L.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. The Effect of Human Trampling Activity on a Soil Microbial Community at the Urban Forest Park. Forests 2023, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, F.R. A Review of Major Factors Influencing Plant Responses to Recreation Impacts. Environ. Manage. 1986, 10, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, R.W.; Ward, R.T. Phenology and Growth of Rocky Mountain Populations of Deschampsia Caespitosa at Three Elevations in Colorado. Ecology 1972, 53, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECOLOGICAL IMPACT OF CAMPING UPON THE SOUTHERN SIERRA NEVADA - ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8bdb0fa22b4747cbafa2b8f68647dfef/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Holmes, D.O.; Dobson, H.E.M. The Effects of Human Trampling and Urine on Subalpine Vegetation, a Survey of Past and Present Backcountry Use, and the Ecological Carrying Capacity of Wilderness: Final Report, Ecological Carrying Capacity Research Contract CX8000-4-0026. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kycko, M.; Zagajewski, B.; Lavender, S.; Romanowska, E.; Zwijacz-Kozica, M. The Impact of Tourist Traffic on the Condition and Cell Structures of Alpine Swards. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, J.; Lagerström, A. High Species Turnover and Decreasing Plant Species Richness on Mountain Summits in Sweden: Reindeer Grazing Overrides Climate Change. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2008, 40, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, N.I.; Wipf, S.; Rixen, C.; Beilstein, A.; Doak, D.F. Local Trampling Disturbance Effects on Alpine Plant Populations and Communities: Negative Implications for Climate Change Vulnerability. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 7921–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, N.I.; Rixen, C.; Wipf, S.; Doak, D.F. Human Trampling Disturbance Exerts Different Ecological Effects at Contrasting Elevational Range Limits. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, I.S. Climatic Effects on Glacier Distribution Across the Southern Coast Mountains. B.C., Canada. Ann. Glaciol. 1990, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevington, A.R.; Menounos, B. Accelerated Change in the Glaciated Environments of Western Canada Revealed through Trend Analysis of Optical Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada Census of Population 2021. 2023.

- BC Parks. 2008/09 BC Parks Year End Report; Ministry of Environment: Victoria, 2009; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- BC Parks. BC Parks 2015/16 Statistics Report; Ministry of Environment: Victoria, BC, 2016; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- BC Parks. BC Parks 2017/18 Statistics Report; Ministry of Environment: Victoria, BC, 2018; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, C.G. Can Montane Landscapes Recover from Human Disturbance? Long-Term Evidence from Disturbed Subalpine Communities. Biol. Conserv. 1995, 74, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E. Squamish Nation Culturally Significant Vegetation n.d.

- Martin, K. D.H. Johnson and T. A. O’Neil (Managing Directors). Wildlife-Habitat Relationships in Oregon and Washington; Oregon State University Press: Corvallis, 2001; Volume 2001, p. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vowles, T.; Björk, R.G. Implications of Evergreen Shrub Expansion in the Arctic. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N. Experimental Trampling of Vegetation. II. Predictors of Resistance and Resilience. J. Appl. Ecol. 1995, 32, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, M.-P.; Paré, M.C.; Buttò, V.; Delagrange, S.; Lafond, J.; Deslauriers, A. How Plant Allometry Influences Bud Phenology and Fruit Yield in Two Vaccinium Species. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.C.; Takeno, K. Stress-Induced Flowering. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evju, M.; Hagen, D.; Hofgaard, A. Effects of Disturbance on Plant Regrowth along Snow Pack Gradients in Alpine Habitats. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.D. Patterns of Fruit and Seed Production. In Plant reproductive ecology; Oxford University Press: New York, U.S.A, 1988; pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ciach, M.; Maślanka, B.; Krzus, A.; Wojas, T. Watch Your Step: Insect Mortality on Hiking Trails. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2017, 10, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, P.; Lepš, J. Environmental Correlates of Growth Traits of the Stoloniferous Plant Potentilla Palustris. Evol. Ecol. 2008, 22, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G. Altitudinal Patterns of Maximum Plant Height on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Plant Ecol. 2018, 11, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.R.; Ettinger, A.K.; Lundquist, J.D.; Raleigh, M.S.; Hille Ris Lambers, J. Spatial Heterogeneity in Ecologically Important Climate Variables at Coarse and Fine Scales in a High-Snow Mountain Landscape. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, W. The Ecology of the Alpine Zones; BC Ministry of Forests and Range Research: Victoria, BC, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mote, P.W.; Hamlet, A.F.; Clark, M.P.; Lettenmaier, D.P. DECLINING MOUNTAIN SNOWPACK IN WESTERN NORTH AMERICA*. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 86, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lute, A.C.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Hegewisch, K.C. Projected Changes in Snowfall Extremes and Interannual Variability of Snowfall in the Western United States. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Aschero, V.; Mazzolari, A.; Cavieres, L.A.; Pickering, C.M. Going off Trails: How Dispersed Visitor Use Affects Alpine Vegetation. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 267, 110546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P.E.; Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Jarošík, V.; Schaffner, U.; Vilà, M. Greater Focus Needed on Alien Plant Impacts in Protected Areas. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J.C.; Villanueva, E.M.; Bauman, T.A. Native and Invasive Bunchgrasses Have Different Responses to Trail Disturbance on California Coastal Prairies. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, J.C.; Benavides, J.C. Simulated Small Scale Disturbances Increase Decomposition Rates and Facilitates Invasive Species Encroachment in a High Elevation Tropical Andean Peatland. Biotropica 2015, 47, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, E.M. Invasion Prediction on Alaska Trails: Distribution, Habitat, and Trail Use. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2011, 4, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembrechts, J.J.; Milbau, A.; Nijs, I. Alien Roadside Species More Easily Invade Alpine than Lowland Plant Communities in a Subarctic Mountain Ecosystem. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89664–e89664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C. Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpine Tundra Zone. Ecosystems of British Columbia; Meidinger, D.V., Pojar, J., Eds.; Special report series; Research Branch, Ministry of Forests: Victoria, B.C, 1991; pp. 264–274. ISBN 978-0-7718-8997-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceland, J.; Macaree, D.; Macaree, M. 103 Hikes in Southwestern British Columbia; Greystone Books: Canada, 2008; ISBN 978-1-926685-02-1. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2023.

- GPS Visualizer. Available online: https://www.gpsvisualizer.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bonser, S.P. Size and Phenology Control Plant Reproduction and Agricultural Production. A Commentary on: ‘How Plant Allometry Influences Bud Phenology and Fruit Yield in Two Vaccinium Species.’. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, vi–vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J.; Rosenmeier, L.; Massoni, E.S.; Vera, J.N.; Plaza, E.H.; Sebastià, M.-T. Is Reproductive Allocation in Senecio Vulgaris Plastic? Botany 2009, 87, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. LmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Python Software Foundation. 2021.

- Bürkner, P.-C. Brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P.-C. Advanced Bayesian Multilevel Modeling with the R Package Brms. R J. 2018, 10, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P.-C. Bayesian Item Response Modeling in R with Brms and Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2021, 100, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, M.; Stukalov, A.; Denwood, M. Rjags: Bayesian Graphical Models Using MCMC. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.-S.; Yajima, M. R2jags: Using R to Run “JAGS”. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gabry, J.; Simpson, D.; Vehtari, A.; Betancourt, M.; Gelman, A. Visualization in Bayesian Workflow. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2019, 182, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabry, J.; Mahr, T. Bayesplot: Plotting for Bayesian Models. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vehtari, A.; Gelman, A.; Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian Model Evaluation Using Leave-One-out Cross-Validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 2017, 27, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehtari, A.; Gabry, J.; Magnusson, M.; Bürkner, P.-C.; Paananen, T.; Gelman, A. Loo: Efficient-Leave-One-out Cross-Validation and WAIC for Bayesian Models. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kallioinen, N.; Bürkner, P.-C.; Paananen, T.; Vehtari, A. Priorsense: Prior Diagnostics and Sensitivity Analysis. 2023. [Google Scholar]

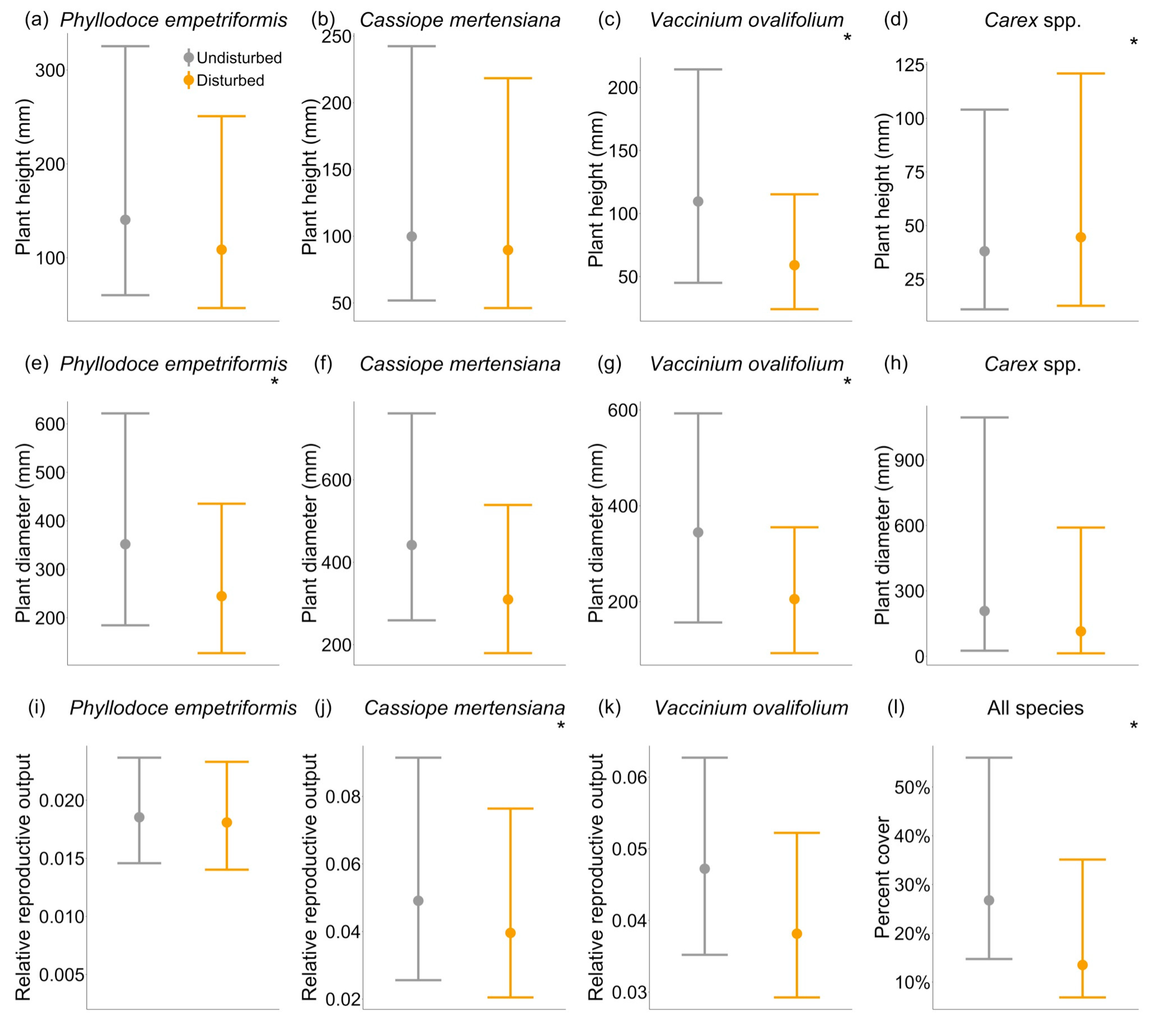

| Species | Trait | N | Intercept | Disturbance | Elevation | Dist*Elev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [All Plants] | Percent Cover | 267 | 6.58 ( 0.34 , 12.61 ) | -8.38 ( -12.56 , -4.4 ) | 0 ( -0.01 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0.01 ) |

| P. empetriformis | Height | 500 | 7.04 ( 2.27 , 11.87 ) | -0.44 ( -3.05 , 2.11 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) |

| Diameter | 500 | 10.48 ( 6.66 , 14.16 ) | -7.15 ( -10.53 , -3.85 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0.01 ) | |

| Reproduction | 500 | -4.77 ( -7.78 , -1.76 ) | 0.39 ( -3.47 , 4.22 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | |

| C. mertensiana | Height | 429 | 7.84 ( 3.73 , 12.04 ) | 0.66 ( -1.27 , 2.59 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) |

| Diameter | 429 | 9.44 ( 5.9 , 12.98 ) | -2.51 ( -5.13 , 0.17 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | |

| Reproduction | 429 | 0.66 ( -4.18 , 5.38 ) | -4.28 ( -8.13 , -0.52 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | |

| V. ovalifolium | Height | 634 | 2.1 ( -4.54 , 8.75 ) | -4.6 ( -7.41 , -1.84 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0.01 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) |

| Diameter | 634 | 6.39 ( -0.05 , 12.96 ) | -9.18 ( -12.34 , -5.99 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0.01 ( 0 , 0.01 ) | |

| Reproduction | 634 | -4.5 ( -7.93 , -0.73 ) | -3.76 ( -7.99 , 0.33 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | 0 ( 0 , 0 ) | |

| Carex spp. | Height | 209 | 22.85 ( 5.06 , 39.25 ) | -20.04 ( -30.96 , -9.37 ) | -0.01 ( -0.02 , 0 ) | 0.01 ( 0.01 , 0.02 ) |

| Diameter | 209 | -6.29 ( -29.7 , 16.07 ) | 11.98 ( -0.5 , 23.86 ) | 0.01 ( -0.01 , 0.02 ) | -0.01 ( -0.01 , 0 ) |

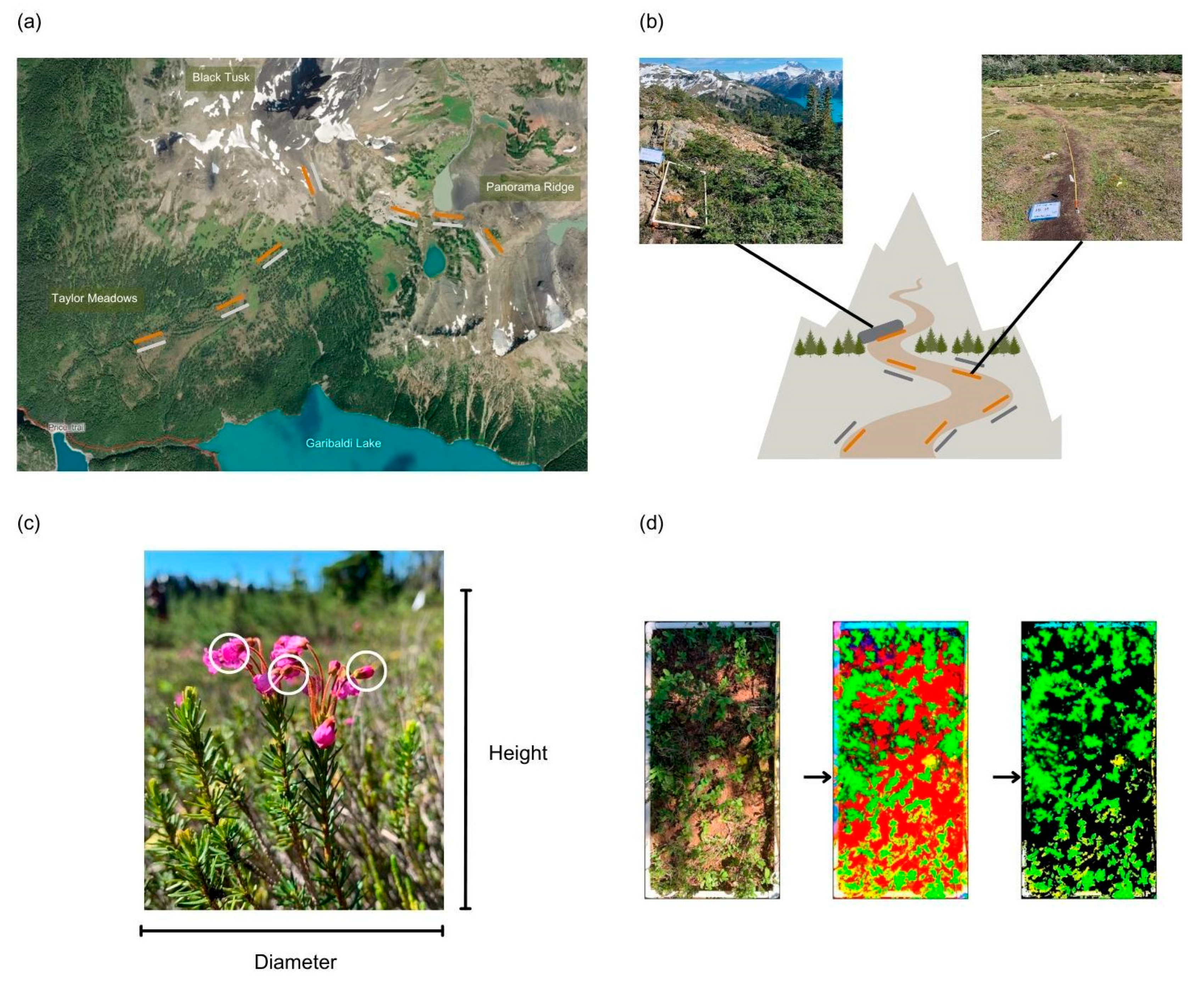

| Parameter | Method | Unit of Measurement | Spatial Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum plant height | Field measurement | Plant | 0.0001 - 1 m |

| Maximum plant diameter | Field measurement | Plant | 0.002 - 1.5 m |

| Reproductive Structures(buds + flowers + fruits) | Field counts | Plant | 0.0001 - 1.5 m |

| Plant Percent Cover | Computed from field photos | Quadrat | 1 x 0.5 m |

| Elevation | Computed from field lat/long | Transect | 30 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).