Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Fractal Evolution

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compilation of Data Sets and Taxonomic Groups

2.2. Artificial Intelligence as Software

2.3. Alternative Methods

3. Results

3.1. Constants

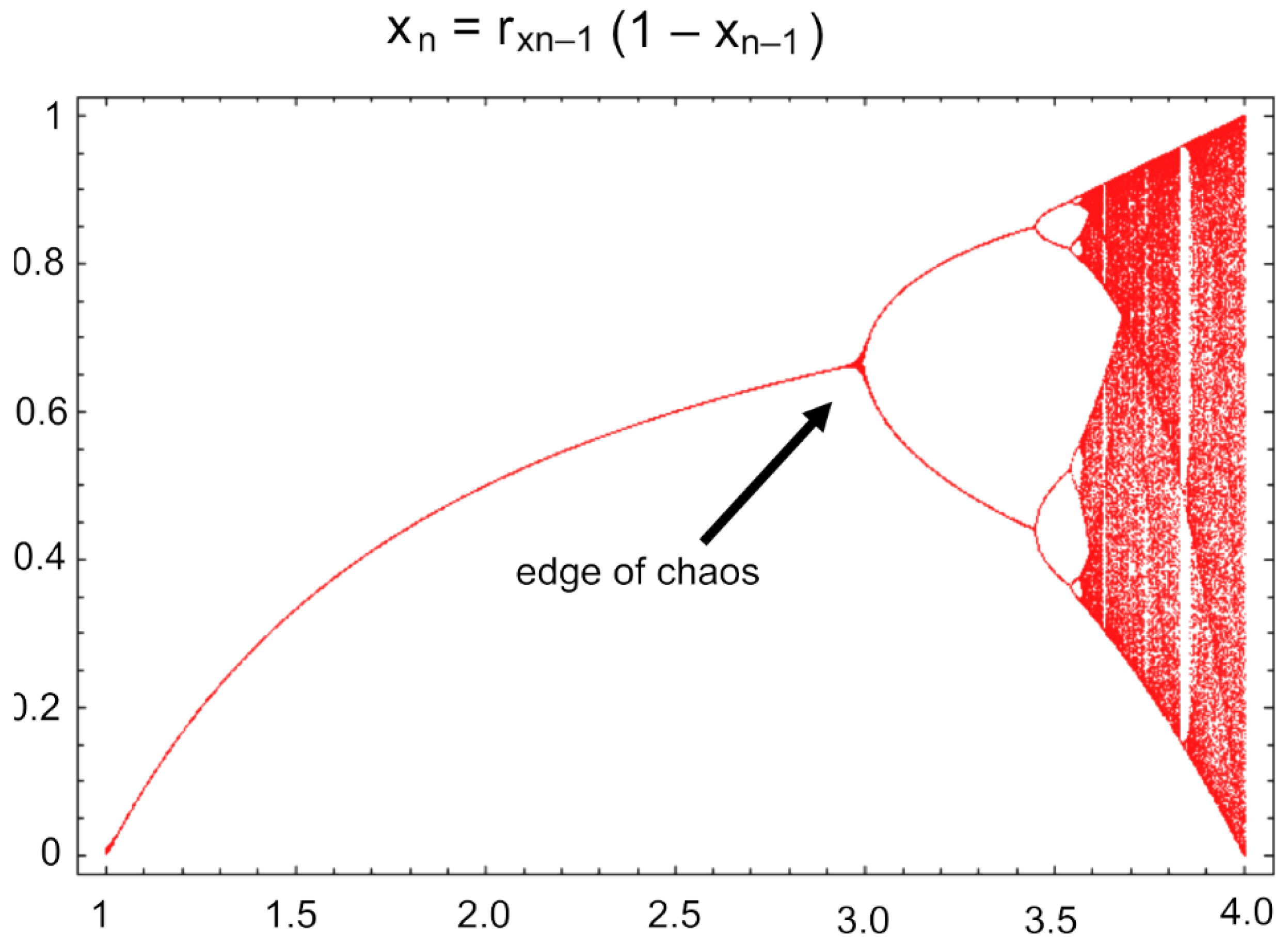

3.1.1. The Feigenbaum Constant

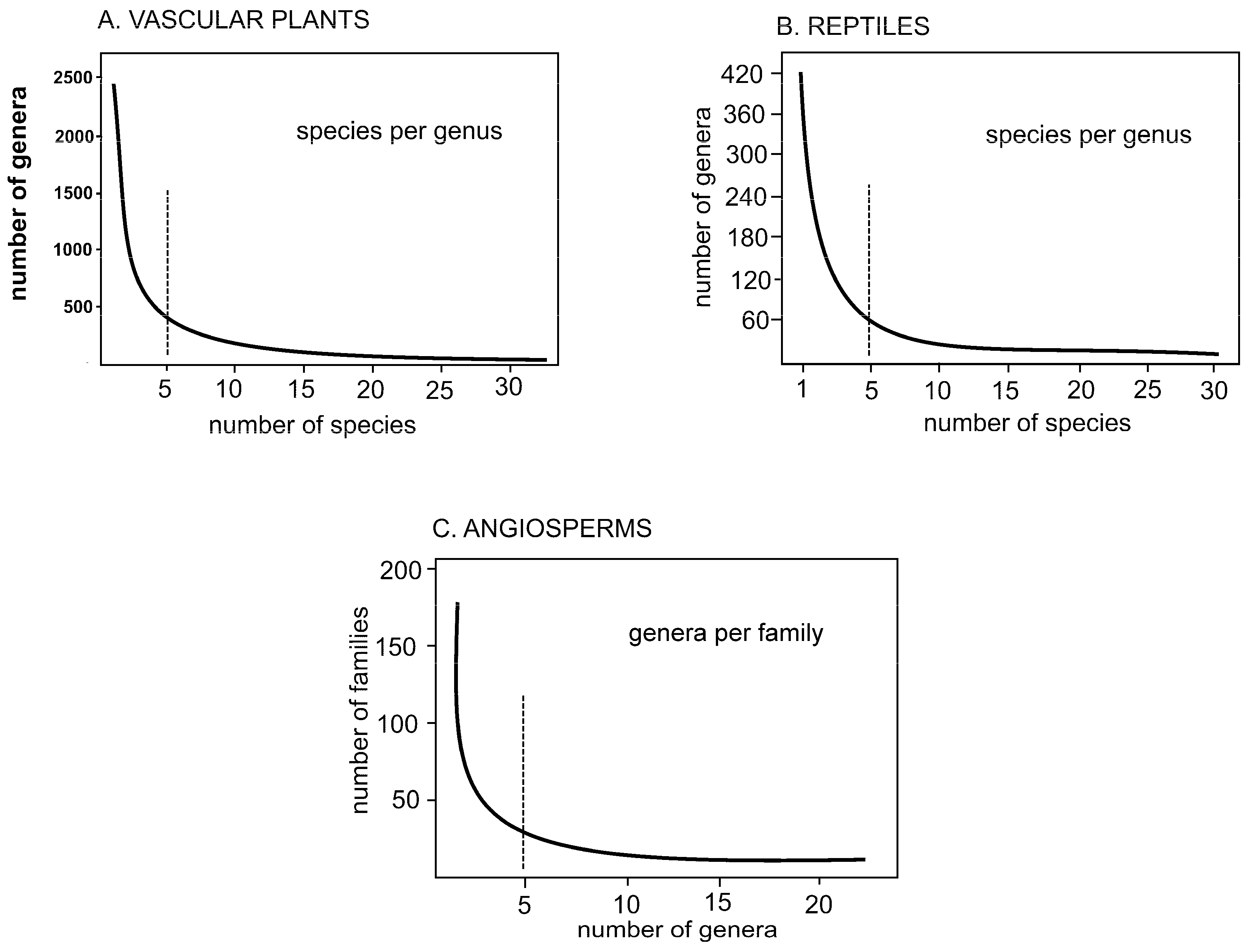

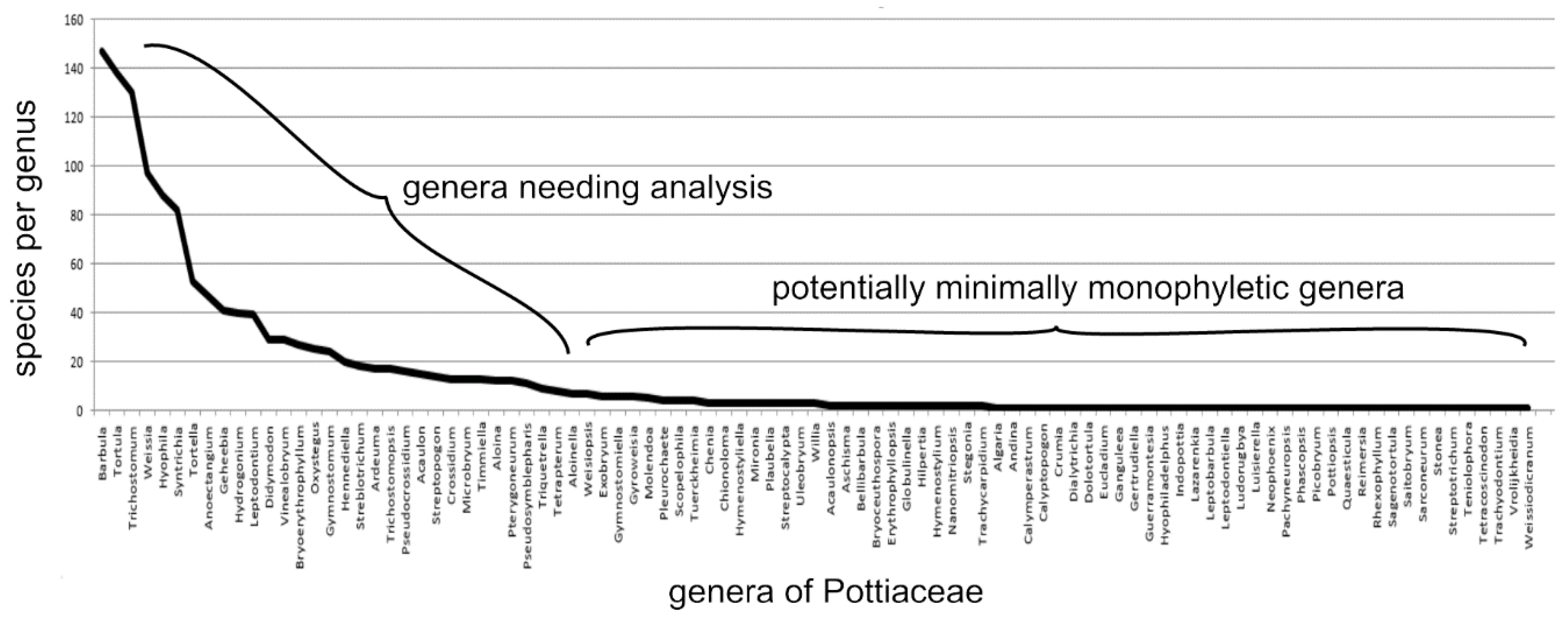

3.1.2. Zipf’s Law

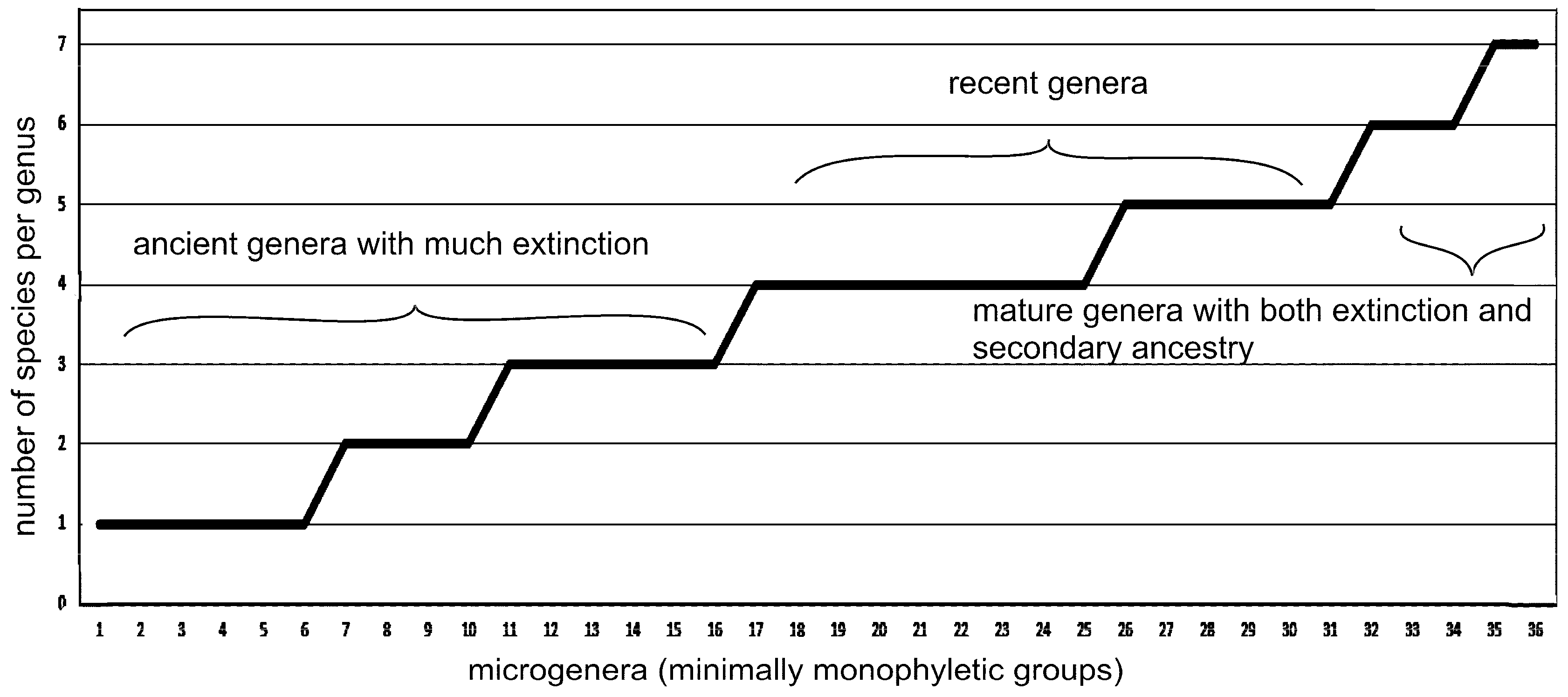

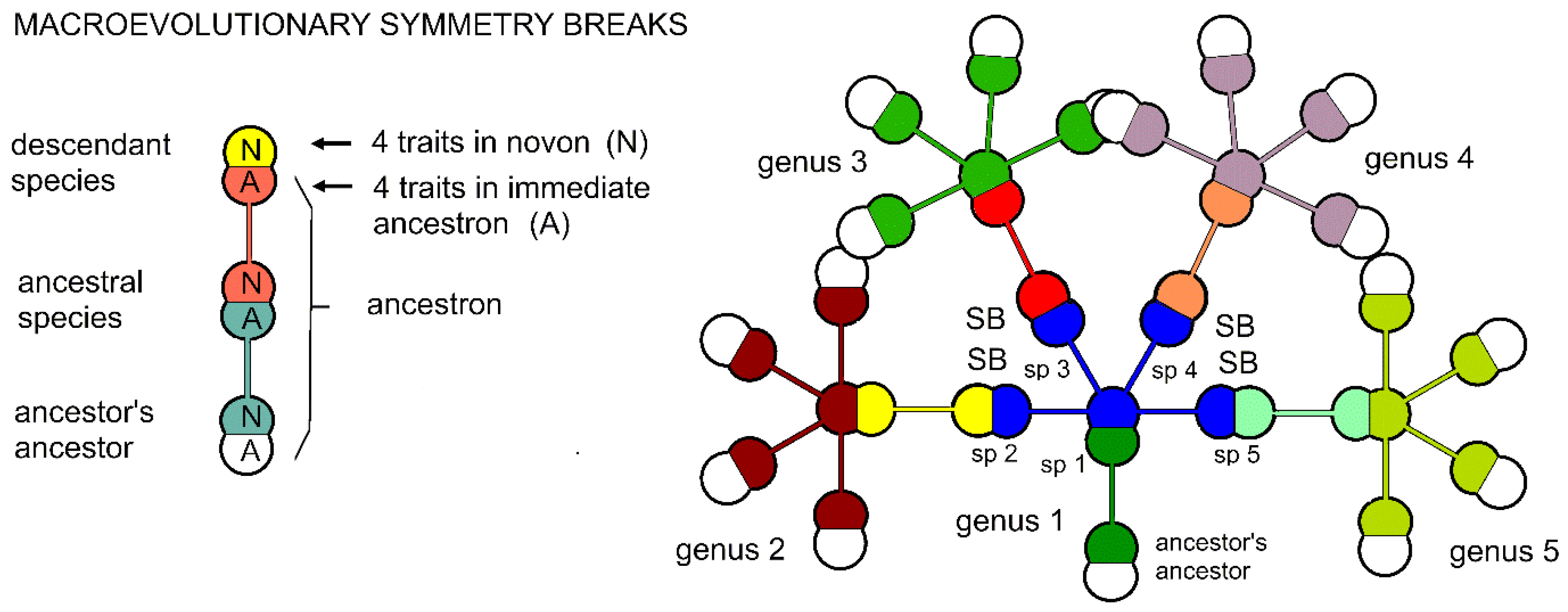

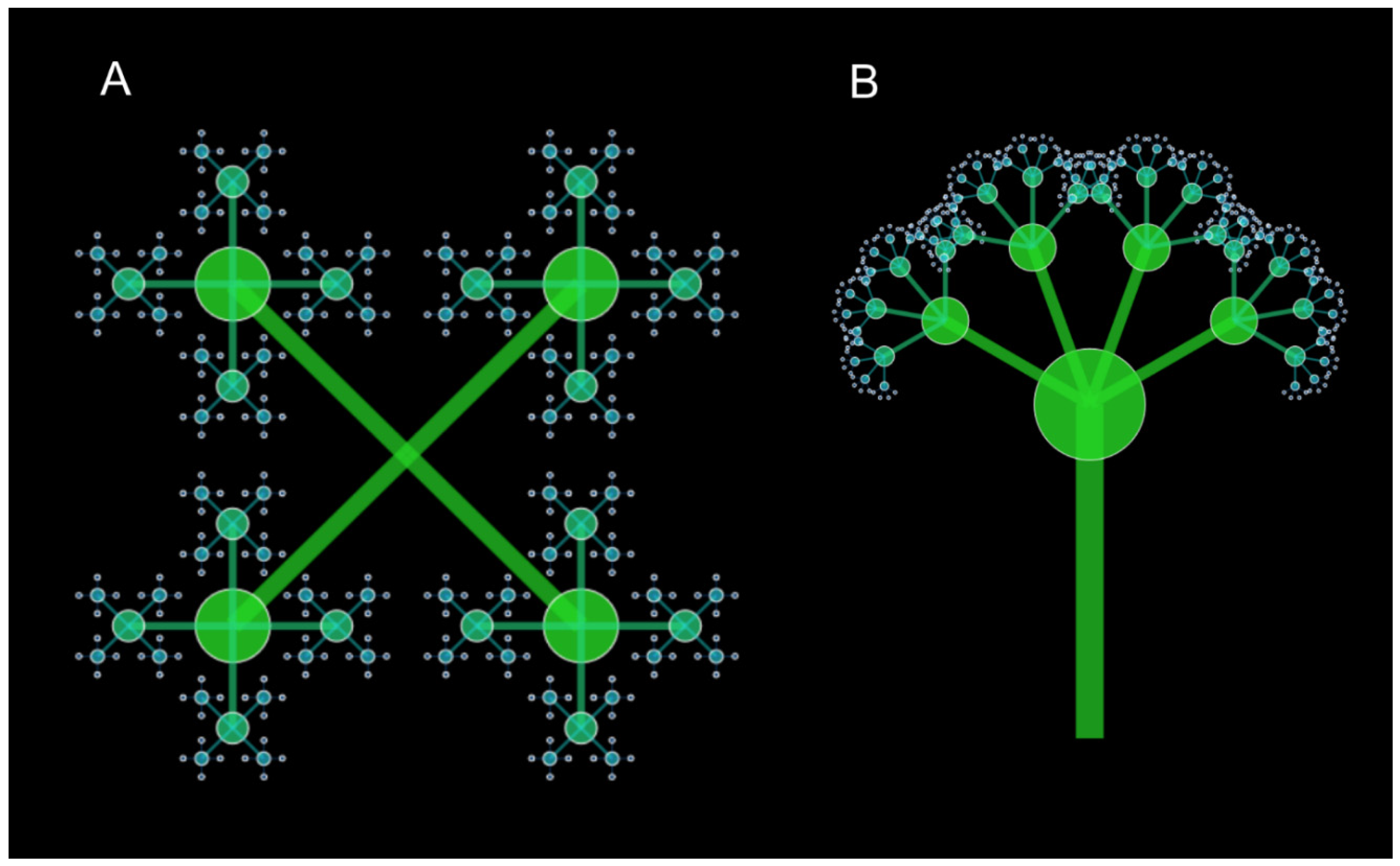

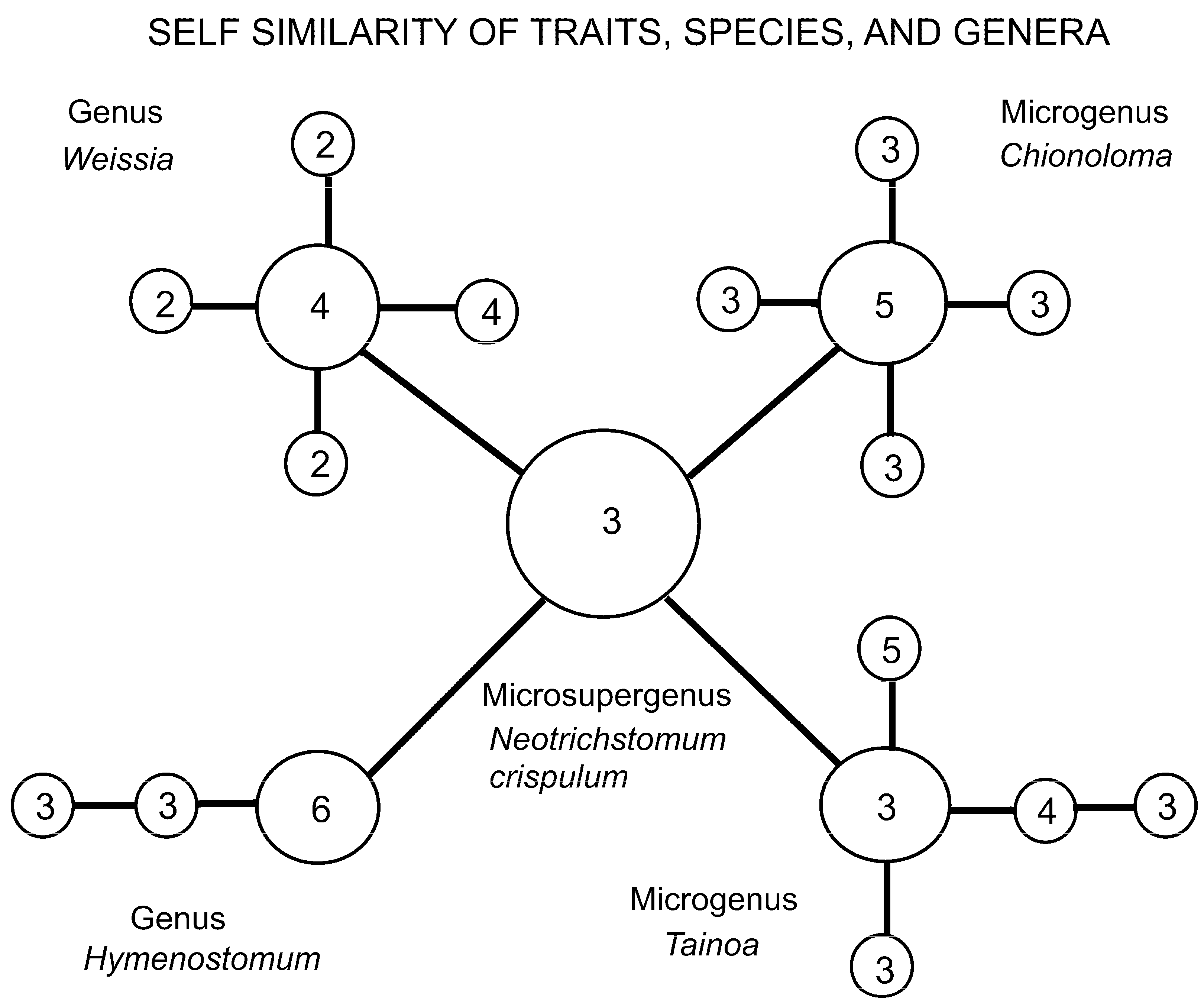

3.2.3. Fractal Representation of Macroevolution

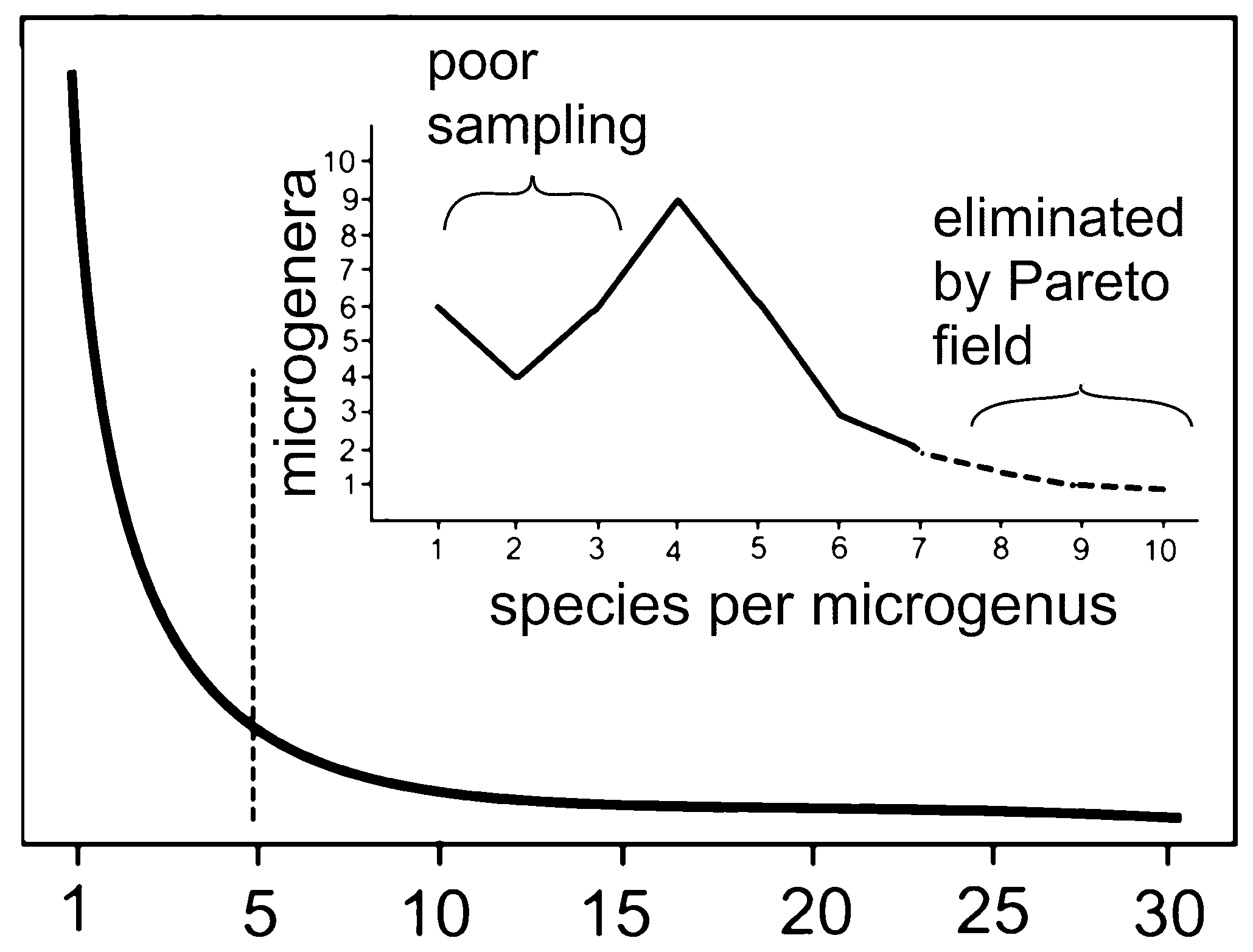

3.2.3. The Fractal Dimension and Pareto distribution

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecological Resilience

4.2. Chaos

4.3. Complexity and Fractals

4.4. Combining the Laws

4.4.1. Extinction

4.4.2. Common Ancestry Analysis

5. Conclusions

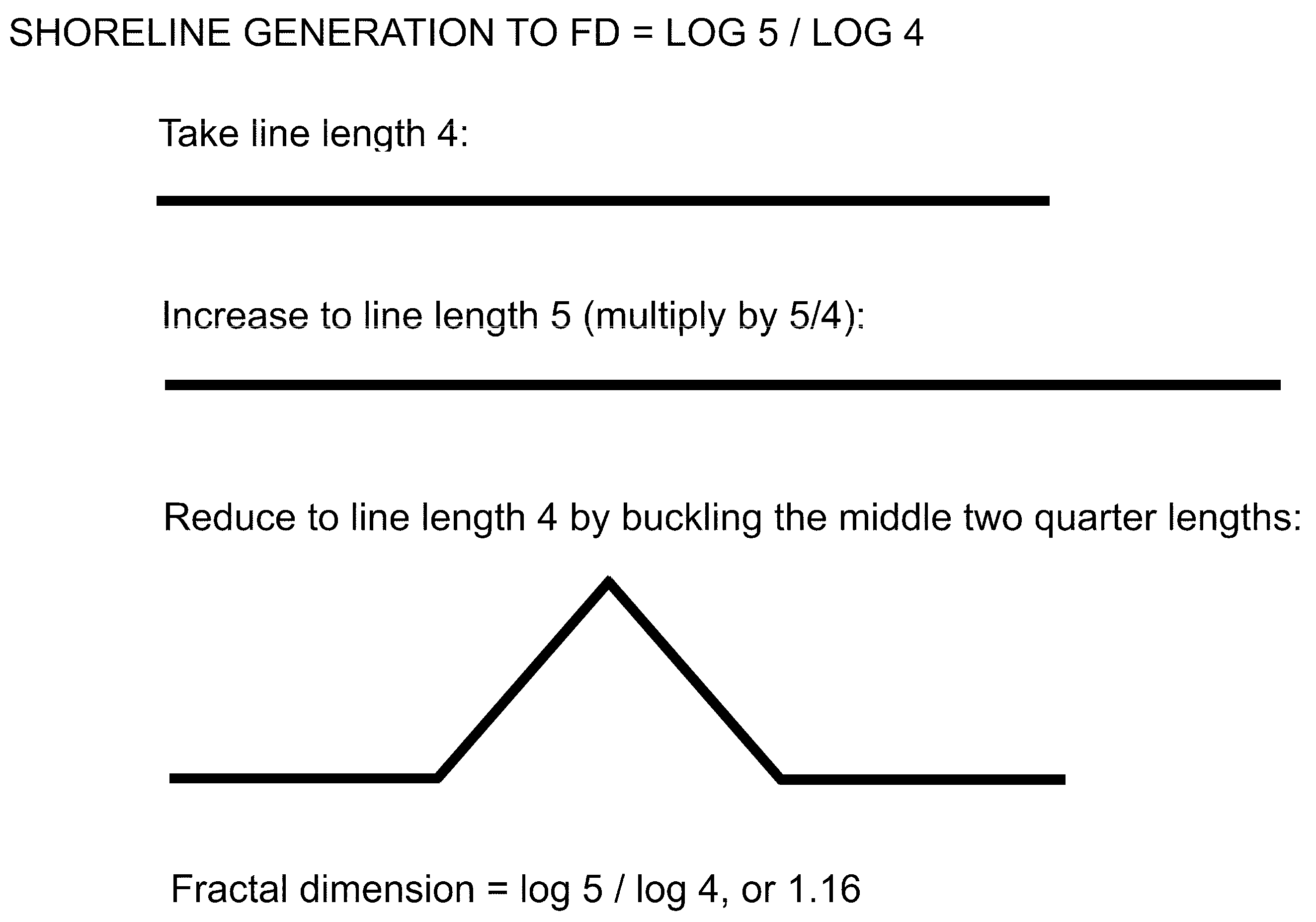

- 4-way branching creates square-based spatial filling, or 22-fold symmetry. Thus the system models spatial filling.

-

The following conservation laws are followed,

- ○

- Area conservation: 4r2 = 1.

- ○

- Flow conservation: 4rD = 1.

- ○

- Resource distribution: 5rD = 1.

- ○

- ln4 models complete spacial filling in 2D.

- ○

- ln5 models slightly more resource demand.

- The ratio ln4:ln5 balances spatial coverage versus resource needs.

- is optimal continuous scaling.

-

Dimensional analysis,

- ○

- D1 linear chains are insufficient.

- ○

- D2 square filling is optimal for 4-way branching.

- ○

- D3 cubic space is potentially overcrowded.

- ○

- D4 hypercube is probably inefficient.

-

Scaling ratio:

- ○

- The scaling ratio, that is, how the length of the descendant branch is shorter than that of the ancestral branch, is r = e–1/α where α = ln5/ln4 ≈ 1.161. Thus r ≈ 0.423, which is optimum continuous (self-similarity) scaling.

- ○

- This is optimum because it balances flow, 4rD = 1 (4 branches preserve total flow), and resources, 5rD = 1 (5 units needed per 4 branches).

- ○

- α = ln5/ln4 ≈ 1.161 the balance between needs and flow.

-

Information optimality:

- ○

- α is the ratio of bits encoding ancestor and descendant states.

- ○

- Branching adds information: n × ln4.

- ○

- Information is lost through scaling: –n × ln5, reducing distinguishability.

- ○

- Information content is therefore negative and decreases linearly with depth (recursion), which represents increasing entropy in the system.

- ○

- Optimal rate of information loss balances system growth against system collapse.

- ○

-

Ratio ln5/ln4 balances by

- ▪

- Rate of information loss = ln5/ln4 ≈ 0.223 bits per level.

- ▪

- Total information at level n ≈ –0.223n bits.

- ○

- This leads to self-similarity and stable complexity, optimizing information compression.

Funding

Supplemental Materials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sokal, R.R.; Sneath, P.H.A. Principles of numerical taxonomy. San Francisco (CA): W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1963.

- Krakauer, D.C.; Collins; J.P.; Erwin, D.; Flack, J.D.; Fontana, W.; Laubichler, M.D.; Prohaska, S.J.; West, G.B.; Stadler, P.F. The challenges and scope of theoretical biology. J. Theor. Biol. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Minimally monophyletic genera are the cast-iron building blocks of evolution. Ukr. Bot. J. 2024, 81, 87–99. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Lineages of fractal genera comprise the 88-million-year steel evolutionary spine of the ecosphere. Plants 2024, 13, 1559. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. The steel evolutionary spine revisited, with implications and consequences. Contemporary Research and Perspectives in Biological Science Vol. 1. 2024, Sept.,154–185. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Fractal Evolution, Complexity and Systematics. Zetetic Publications, St. Louis, 2023.

- Zander R.H. Integrative systematics with structural monophyly and ancestral signatures: Chionoloma (Bryophyta). Academia Biology 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Macroevolutionary Systematics of Streptotrichaceae of the Bryophyta and Application to Ecosystem Thermodynamic Stability, ed. 2. Zetetic Publications, St. Louis, 2018.

- Zander, R.H. Evolutionary leverage of dissilient genera of Pleuroweisieae (Pottiaceae) evaluated with Shannon-Turing analysis. Hattoria 2021, 12: 9–25.

- Brooks, D.R.; Wiley, E.O. Evolution as Entropy: Toward a Unified Theory of Biology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 1988.

- Ellis, G.F.R.; Di Sia, P. Complexity theory in biology and technology: broken symmetries and emergence. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1945. [CrossRef]

- Packard, N.H. Adaptation towards the Edge of Chaos. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Center for Complex Systems Research. Urbana, Illinois, 1988.

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry and Engineering. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., U.S.A. 1994.

- Aitchison, L.; Corradi, N.; Latham, P.E. Zipf’s Law arises naturally when there are underlying, unobserved variables. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, 12. e1005110. [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Geometric models of speciation in minimally monophyletic genera using High-Resolution Phylogenetics. Plants 2025, 14, 530. [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, D.C. Symmetry–simplicity, broken symmetry–complexity. Interface Focus 2023, 13, (20220075), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.L. A Primer of Population Genetics and Genomics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020.

- Plotnick, R.E.; Sepkoski, J.J., Jr.. A multiplicative multifractal model for originations and extinctions. Paleobiology 2001, 27, 126–139.

- Ruvalcaba, Z.; Boehm, A. Murach’s HTML5 and CSS3. Training and Reference. Mike Murach & Associates, Fresno, California, 2012.

- Barnsley, M.F.; Demko, S. Iterated functions systems and the global construction of fractals. Proc. R. Soc. London. A 1985, 399, 243–275. [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M. Fractals Everywhere. Academic Press, New York, 1988.

- Barnsley M.F.; Vince, A. The chaos game on a general iterated function system. Ergodic Theory and Dynamical Systems. 2011, 31,1073–1079. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.E. Fractals and self similarity. Indiana University Math. J. 1981, 30, 713–747. [CrossRef]

- Guy, R.K. The strong law of small numbers. Amer. Math. Monthly 1988, 95, 697–712.

- Tryon, E. Is the universe a vacuum fluctuation? Nature 1973, 246, 396–397. [CrossRef]

- Harte, J.; Newman, E.A. Maximum information entropy: a foundation for ecological theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2014, 29, 384–389. [CrossRef]

- Gazzarrini, E.; Cersonsky, R.K.; Bercx, M.; Adorf, C.S.; Marzari, N. The rule of four: anomalous distributions in the stoichiometries of inorganic compounds. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 73.

- Constantin, A.; Bartlett, D.; Desmond, H.; Ferreira, P.G. Statistical patterns in the equations of physics and the emergence of a meta-law of nature. Arxiv 2024, arXiv:2408.11065.

- Mandelbrot, B. The Pareto-Lévy Law and the Distribution of Income. International Economic Review, 1960,1, 79–106.

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H. Life’s Universal Scaling Laws. Physics Today 2004, 57, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J. D. The Constants of Nature. Pantheon Books, New York, 2002.

- Gleick, J. Chaos: Making a New Science. Penguin Books, New York, 1987.

- Infeld, E.; Rowlands. G. Nonlinear Waves, Solitons and Chaos. Cambridge University Press, New York, 2000.

- Pimm, S. L. The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 1984. 307: 321–324.

- Schroeder, M. Fractals, Chaos, Power Laws, Minutes from an Infinite Paradise. W. H. Freeman, New York, 1991.

- Hastings, A.; Powell, T.. Chaos in a three-species food chain. Ecology 1991, 72, 896–903. [CrossRef]

- Bak, P.; Tang, C.; Wiesenfeld, K. “Self-organized criticality”. Physical Review A 1988, 38, 364–374. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. A. Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992.

- Lewin, R. Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999.

- Eldredge, N. Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1985.

- Weisstein, E. W.. “Logistic Map.” From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. 2025. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/LogisticMap.html Viewed 8 March 2025.

- Wilkins, A. The laws of physics appear to follow a mysterious mathematical pattern. New Scientist 2024, 21 October 2024. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2452341-the-laws-of-physics-appear-to-follow-a-mysterious-mathematical-pattern/ Viewed 4 March 2025.

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. Updated and augmented. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, 1983.

- Newman, M.E.J. Power laws, Pareto distributions, and Zipf’s law. Contemporary Physics 2005, 46, 323–351.

- Newberry, M. Art and science illuminate the same subtle proportions in tree branches. The Conversation 2025, 11 February 2025 https://theconversation.com/art-and-science-illuminate-the-same-subtle-proportions-in-tree-branches-247967.

- Darwin, C. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Washington Square Press, New York. 1963 Edition, 1859.

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological resilience—In theory and application. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439.

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23.

- Ludwig, A.K.; Barnes, C.D.; Fogart,y D.; Fowler, J.A.; Hogan, I.F.E.; Johnson, J.E.; Twidwell, D. Ecological Resilience. Plant and Soil Sciences eLibrary Lessons https://passel2.unl.edu/view/lesson/d6c3e24cbc7e 2020. Accessed Dec. 28, 2025.

- Weber, B.H.; Depew, D.J.; Smith, J.D., eds. Entropy, Information, and Evolution: New Perspectives on Physical and Biological Evolution. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1990.

- Gott, J.R. Time Travel in Einstein’s Universe. Houghton Mifflin, New York, 2001.

- Poundstone, W. The Doomsday Calculation. Little, Brown Spark, New York, 2019.

- Sheffield, C. Borderlands of Science. Baen Books, Riverdale New York, 1999.

- Lurie, R.M. “Classic Logistic Map” Heikki Ruskeepää 2011. Wolfram Demonstrations Project. https://demonstrations.wolfram.com/ClassicLogisticMap/ Accessed 2 Feb. 2025.

- Waldrop, M.M. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1992.

- Gross, D.J. The role of symmetry in fundamental physics, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 14256–14259. [CrossRef]

- Wegsman, S. How Noether’s theorem revolutionized physics. Quanta Newsletter Feb. 7, 2025. https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-noethers-theorem-revolutionized-physics-20250207/ Viewed February 27, 2025.

- Nicolis G.; Prigogine I. Exploring Complexity: An Introduction. W.J.H. Freeman and Company, New York, 1989.

- Gleick, J. The Information, A History, A Theory, A Flood. Pantheon Books, New York, 2011.

- Kline, M. Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980.

- Hughes, B.D. Reed, W.J. A problem in paleobiology. arXiv.physics/0211090V1 [physics.bio-oph] 2002. 20 Nov. 2002. https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0211090v1 Viewed 14 March 2025.

- Stevens, P.F. The genus concept in practice: but for what practice? Kew Bull. 1985, 40, 457–465.

- Stevens, P.F. Why do we name organisms? Some reminders from the past. Taxon. 2002, 51, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, A.M.; Linder, H.P. Concept versus data in delimitation of plant genera. Taxon 2009, 58, 1054–1074.

- Mishler, B.D. What, if Anything, are Species? CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2021.

- Feynman, R. Nobel Lecture. Nobel Foundation, 1965. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1965/feynman-lecture.html.

- Humphreys, A.M.; Barraclough, T.G. The evolutionary reality of higher taxa in mammals. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20132750. [CrossRef]

- Harré, R. The Philosophies of Science. An Introductory Survey. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1972.

- Hughes, M. The Gist Hunter. Nightshade Books, New York, 2014.

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. A general model for the structure and allometry of plant vascular systems. Nature 1999, 400(6745), 664–667. [CrossRef]

- Borchert, R.; Slade, N.A.. Bifurcation ratios and the adaptive geometry of trees. Bot. Gaz. 1981, 142, 304–401.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).