Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Global Shortage of Pathologists

Effect on Endoscopic Duodenal Biopsies

Diagnosing Coeliac Disease in Endoscopic Duodenal Biopsies

Pathologists’ Discordance in Biopsy-Based Coeliac Disease Diagnosis

Digital Pathology

Rationale for Audit

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

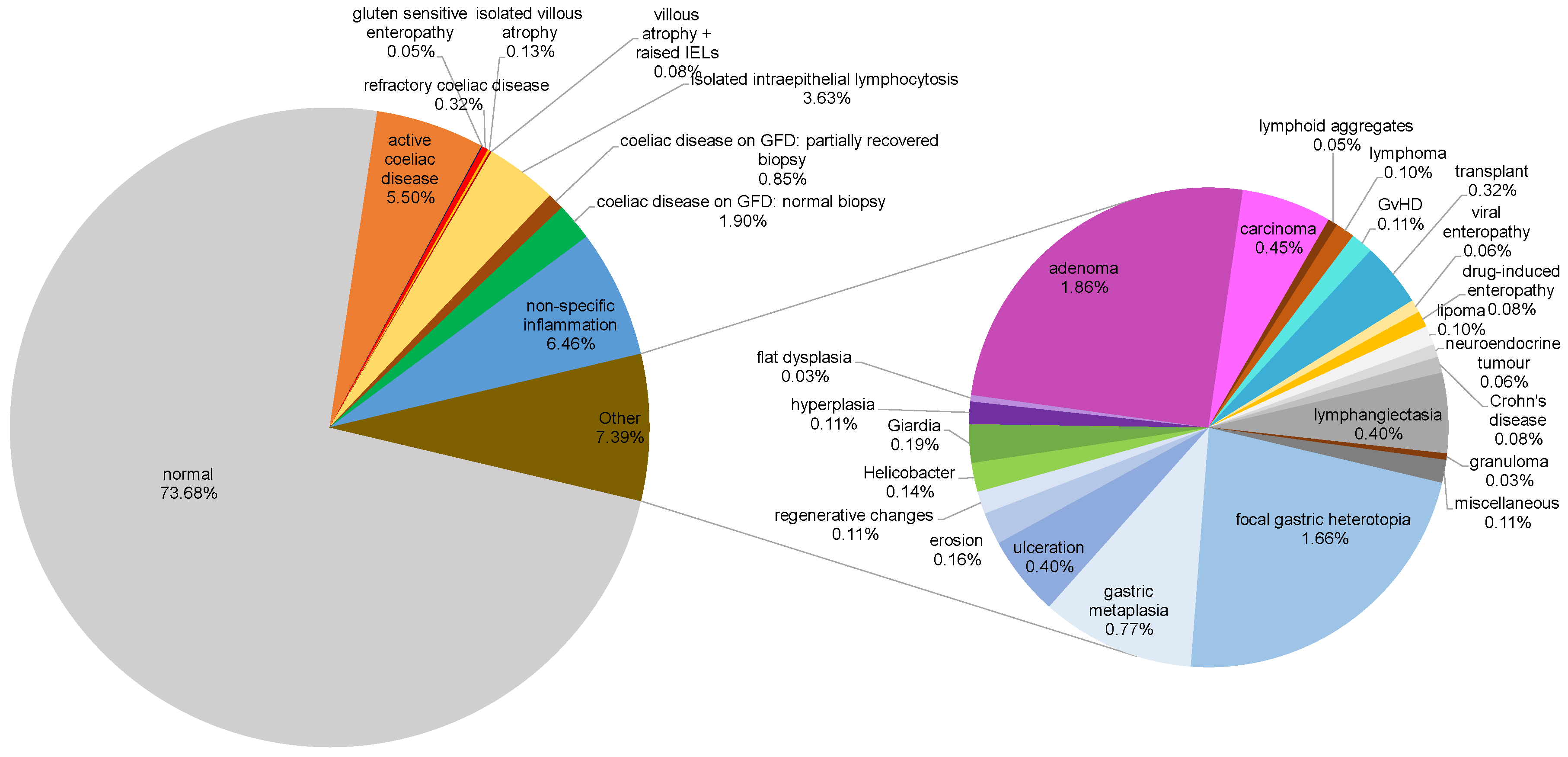

3.1. Breakdown of Diagnostic Categories

3.2. Keywords for Minor Diagnostic Categories

3.3. Isolated Intraepithelial Lymphocytosis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Metter, D.M.; Colgan, T.J.; Leung, S.T.; Timmons, C.F.; Park, J.Y. Trends in the US and Canadian Pathologist Workforces From 2007 to 2017. JAMA Network Open 2019, 2, e194337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APW.Pdf. Available online: https://www.rcpa.edu.au/getattachment/4a38b4f9-5f6a-45eb-8947-dfa072797685/APW.aspx (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Märkl, B.; Füzesi, L.; Huss, R.; Bauer, S.; Schaller, T. Number of Pathologists in Germany: Comparison with European Countries, USA, and Canada. Virchows Arch 2021, 478, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robboy, S.J.; Weintraub, S.; Horvath, A.E.; Jensen, B.W.; Alexander, C.B.; Fody, E.P.; Crawford, J.M.; Clark, J.R.; Cantor-Weinberg, J.; Joshi, M.G.; Cohen, M.B.; Prystowsky, M.B.; Bean, S.M.; Gupta, S.; Powell, S.Z.; Speights, V.O., Jr; Gross, D.J.; Black-Schaffer, W.S.; additional members of the Workforce Project Work Group. Pathologist Workforce in the United States: I. Development of a Predictive Model to Examine Factors Influencing Supply. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2013, 137, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, V.; Malyangu, E.; Sayed, S.; Fleming, K. Addressing the Shortage of Pathologists in Africa: Creation of a MMed Programme in Pathology in Zambia. Afr J Lab Med 2020, 9, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, A.; Schubert, M. Constant Demand, Patchy Supply. The Pathologist 2023, 88, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Meeting-Pathology-Demand-Histopathology-Workforce-Census-2018.Pdf. https://www.rcpath.org/static/952a934d-2ec3-48c9-a8e6e00fcdca700f/Meeting-Pathology-Demand-Histopathology-Workforce-Census-2018.pdf (accessed 2024-01-22).

- Histopathologists.Pdf. https://www.rcpath.org/static/797e5533-d718-442a-be4ee7e695a5550e/Histopathologists.pdf (accessed 2024-01-19).

- Adesina, A.; Chumba, D.; Nelson, A.M.; Orem, J.; Roberts, D.J.; Wabinga, H.; Wilson, M.; Rebbeck, T.R. Improvement of Pathology in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet Oncology 2013, 14, e152–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnosis. Coeliac UK. https://www.coeliac.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/diagnosis/ (accessed 2024-01-22).

- Downey, L.; Houten, R.; Murch, S.; Longson, D. Recognition, Assessment, and Management of Coeliac Disease: Summary of Updated NICE Guidance. Bmj 2015, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caio, G.; Volta, U.; Sapone, A.; Leffler, D.A.; De Giorgio, R.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Celiac Disease: A Comprehensive Current Review. BMC Med 2019, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- full-guideline-pdf-438530077.pdf. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng20/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-438530077 (accessed 2024-01-22).

- Tsung, J.S.H. Institutional Pathology Consultation. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2004, 28, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frable, W.J. Surgical Pathology—Second Reviews, Institutional Reviews, Audits, and Correlations: What’s Out There? Error or Diagnostic Variation? Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2006, 130, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordi, J.; Castillo, P.; Saco, A.; Pino, M. del; Ordi, O.; Rodríguez-Carunchio, L.; Ramírez, J. Validation of Whole Slide Imaging in the Primary Diagnosis of Gynaecological Pathology in a University Hospital. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2015, 68, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denholm, J.; Schreiber, B.A.; Jaeckle, F.; Wicks, M.N.; Benbow, E.W.; Bracey, T.S.; Chan, J.Y.H.; Farkas, L.; Fryer, E.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hughes, C.A.; Kirkwood, K.J.; Langman, G.; Mahler, B.; McMahon, R.F.T.; Myint, K.L.W.; Natu, S.; Robinson, A.; Sanduka, A.; Sheppard, K.A.; Tsang, Y.W.; Arends, M.J.; Soilleux, E.J. Digital Pathology Reporting of Coeliac Disease: An Inter-Observer Agreement Study.

- Villanacci, V.; Lorenzi, L.; Donato, F.; Auricchio, R.; Dziechciarz, P.; Gyimesi, J.; Koletzko, S.; Mišak, Z.; Laguna, V.M.; Polanco, I.; Ramos, D.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Vriezinga, S.L.; Mearin, M.L. Histopathological Evaluation of Duodenal Biopsy in the PreventCD Project. An Observational Interobserver Agreement Study. APMIS 2018, 126, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picarelli, A.; Borghini, R.; Donato, G.; Di Tola, M.; Boccabella, C.; Isonne, C.; Giordano, M.; Di Cristofano, C.; Romeo, F.; Di Cioccio, G.; Marcheggiano, A.; Villanacci, V.; Tiberti, A. Weaknesses of Histological Analysis in Celiac Disease Diagnosis: New Possible Scenarios. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 2014, 49, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguelles-Grande, C.; Tennyson, C.A.; Lewis, S.K.; Green, P.H.R.; Bhagat, G. Variability in Small Bowel Histopathology Reporting between Different Pathology Practice Settings: Impact on the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J Clin Pathol 2012, 65, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, M.G.; Tonutti, E.; Brusca, I.; Radice, A.; Licini, L.; Sonzogni, A.; Florena, A.; Schiaffino, E.; Marus, W.; Sulfaro, S.; Villalta, D.; Study Group on Autoimmune Diseases of Italian Society of Laboratory Medicine. Correlation between IgA Tissue Transglutaminase Antibody Ratio and Histological Finding in Celiac Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012, 55, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazza, G.R.; Villanacci, V.; Zambelli, C.; Milione, M.; Luinetti, O.; Vindigni, C.; Chioda, C.; Albarello, L.; Bartolini, D.; Donato, F. Comparison of the Interobserver Reproducibility With Different Histologic Criteria Used in Celiac Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2007, 5, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montén, C.; Bjelkenkrantz, K.; Gudjonsdottir, A.H.; Browaldh, L.; Arnell, H.; Naluai, Å.T.; Agardh, D. Validity of Histology for the Diagnosis of Paediatric Coeliac Disease: A Swedish Multicentre Study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 2016, 51, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.; Cairns, A.; Dixon, M.F.; O’Mahony, S. Quantitation of Intraepithelial Lymphocytes in Human Duodenum: What Is Normal? Journal of Clinical Pathology 2002, 55, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, M.N.; Rostami, K. What Is A Normal Intestinal Mucosa? Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhuber, G. Histopathology of Celiac Disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2000, 54, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, P.; Wahab, P.J.; Murray, J.A. Intraepithelial Lymphocytes and Coeliac Disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2005, 19, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S.T.G.; Greenson, J.K. The Clinical Significance of Duodenal Lymphocytosis with Normal Villus Architecture. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013, 137, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.M.; Papanicolas, I.N. Impact of Symptoms on Quality of Life before and after Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease: Results from a UK Population Survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2010, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnosis. Coeliac UK. https://www.coeliac.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/diagnosis/ (accessed 2024-01-22).

- Holten-Rossing, H.; Talman, M.-L. M.; Jylling, A.M.B.; Lænkholm, A.-V.; Kristensson, M.; Vainer, B. Application of Automated Image Analysis Reduces the Workload of Manual Screening of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsies in Breast Cancer. Histopathology 2017, 71, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ström, P.; Kartasalo, K.; Olsson, H.; Solorzano, L.; Delahunt, B.; Berney, D.M.; Bostwick, D.G.; Evans, A.J.; Grignon, D.J.; Humphrey, P.A.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Kench, J.G.; Kristiansen, G.; Kwast, T.H. van der; Leite, K.R.M.; McKenney, J.K.; Oxley, J.; Pan, C.-C.; Samaratunga, H.; Srigley, J.R.; Takahashi, H.; Tsuzuki, T.; Varma, M.; Zhou, M.; Lindberg, J.; Lindskog, C.; Ruusuvuori, P.; Wählby, C.; Grönberg, H.; Rantalainen, M.; Egevad, L.; Eklund, M. Artificial Intelligence for Diagnosis and Grading of Prostate Cancer in Biopsies: A Population-Based, Diagnostic Study. The Lancet Oncology 2020, 21, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, V.; Levine, L.; Solans, E.P.; Dola, S.; Chervony, L.; Polak, S. Performance of Automated Classification of Diagnostic Entities in Dermatopathology Validated on Multisite Data Representing the Real-World Variability of Pathology Workload. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, S.; Huisman, A.; Van Diest, P.J. Digital Pathology: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Histopathology 2012, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, S.W.; Plass, M.; Moinfar, F. Digital Pathology: Advantages, Limitations and Emerging Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening | Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1799-6 (accessed 2023-04-17).

- Denholm, J.; Schreiber, B.A.; Evans, S.C.; Crook, O.M.; Sharma, A.; Watson, J.L.; Bancroft, H.; Langman, G.; Gilbey, J.D.; Schönlieb, C.-B.; Arends, M.J.; Soilleux, E.J. Multiple-Instance-Learning-Based Detection of Coeliac Disease in Histological Whole-Slide Images. Journal of Pathology Informatics 2022, 13, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeckle, F.; Bryant, R.; Denholm, J.; Romero Diaz, J.; Schreiber, B.; Shenoy, V.; Ekundayomi, D.; Evans, S.; Arends, M.; Soilleux, E. Interpretable Machine Learning Based Detection of Coeliac Disease. medRxiv 2025, 2025–03. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeckle, F.; Denholm, J.; Schreiber, B.; Evans, S.C.; Wicks, M.N.; Chan, J.Y.H.; Bateman, A.C.; Natu, S.; Arends, M.J.; Soilleux, E. Machine Learning Achieves Pathologist-Level Celiac Disease Diagnosis. NEJM AI 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, G. UK Biobank Opens Its Data Vaults to Researchers, 2012. https://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e2459.full (accessed 2025-02-19).

- Bahcall, O.G. UK Biobank–a New Era in Genomic Medicine. Nature reviews genetics 2018, 19, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Biobank, Resource 182. https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=182.

- Ting, Y.T.; Dahal-Koirala, S.; Kim, H.S.K.; Qiao, S.-W.; Neumann, R.S.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Petersen, J.; Reid, H.H.; Sollid, L.M.; Rossjohn, J. A Molecular Basis for the T Cell Response in HLA-DQ2.2 Mediated Celiac Disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Bondia, F.; de Batlle, J.; Galván, L.; Buti, M.; Barbé, F.; Piñol-Ripoll, G. Evolution of the Consumption Trend of Proton Pump Inhibitors in the Lleida Health Region between 2002 and 2015. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.; Wazaify, M.; Shawabkeh, H.; Boardley, I.; McVeigh, J.; Van Hout, M.C. A Scoping Review of Non-Medical and Extra-Medical Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). Drug Saf 2021, 44, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, R.J.; Preston, S.L.H. Pylori Infection, Part I: Clinical Burden and Diagnosis. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health 2021, 12, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irritable-Bowel-Syndrome-in-Adults-Qs-Briefing-Paper2.Pdf. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS114/documents/irritable-bowel-syndrome-in-adults-qs-briefing-paper2 (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Context | Thyroid disease: assessment and management | Guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/chapter/Context (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Prevalence | Background information | Hyperthyroidism | CKS | NICE. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hyperthyroidism/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Green, H.D.; Beaumont, R.N.; Thomas, A.; Hamilton, B.; Wood, A.R.; Sharp, S.; Jones, S.E.; Tyrrell, J.; Walker, G.; Goodhand, J.; Kennedy, N.A.; Ahmad, T.; Weedon, M.N. Genome-Wide Association Study of Microscopic Colitis in the UK Biobank Confirms Immune-Related Pathogenesis. J Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Thio, J.; Thomas, R.S.; Phillips, J. Pernicious Anaemia. BMJ 2020, 369, m1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasvol, T.J.; Horsfall, L.; Bloom, S.; Segal, A.W.; Sabin, C.; Field, N.; Rait, G. Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in UK Primary Care: A Population-Based Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevalence and incidence | Background information | Rheumatoid arthritis | CKS | NICE. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/rheumatoid-arthritis/background-information/prevalence-incidence/ (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Prevalence | Background information | Ankylosing spondylitis | CKS | NICE. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/ankylosing-spondylitis/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Prevalence | Background information | Gastrointestinal tract (lower) cancers - recognition and referral | CKS | NICE. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/gastrointestinal-tract-lower-cancers-recognition-referral/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Prevalence | Background information | Gastrointestinal tract (upper) cancers - recognition and referral | CKS | NICE. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/gastrointestinal-tract-upper-cancers-recognition-referral/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Sen, R.; Goyal, A.; Hurley, J.A. Seronegative Spondyloarthropathy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, C.; Cottrell, E.; Edwards, J. Addison’s Disease: Identification and Management in Primary Care. Br J Gen Pract 2015, 65, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhsbt-Annual-Report-on-Intestine-Transplantation-202122.Pdf. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/27817/nhsbt-annual-report-on-intestine-transplantation-202122.pdf (accessed 2023-10-23).

- Delle Fave, G.; Kwekkeboom, D.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Rindi, G.; Kos-Kudla, B.; Knigge, U.; Sasano, H.; Tomassetti, P.; Salazar, R.; Ruszniewski, P.; all other Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Gastroduodenal Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2011, 95, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Total (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Normal | 4606 | 73.68 |

| Coeliac-associated diagnoses | ||

| Active coeliac disease | 344 | 5.50 |

| Coeliac disease on GFD1: normal biopsy | 119 | 1.90 |

| Coeliac disease on GFD: partially recovered biopsy | 53 | 0.85 |

| Refractory coeliac disease | 20 | 0.32 |

| Isolated villous atrophy | 8 | 0.13 |

| Villous atrophy + raised IELs2 | 5 | 0.08 |

| Gluten sensitive enteropathy | 3 | 0.05 |

| Isolated intraepithelial lymphocytosis | 227 | 3.63 |

| Non-specific inflammation | 404 | 6.46 |

| Neoplastic changes | ||

| Adenoma | 116 | 1.86 |

| Carcinoma | 28 | 0.45 |

| Hyperplasia | 7 | 0.11 |

| Lymphoma | 6 | 0.10 |

| Lipoma | 6 | 0.10 |

| Neuroendocrine tumour | 4 | 0.06 |

| Flat dysplasia | 2 | 0.03 |

| Infections | ||

| Giardiasis | 12 | 0.19 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 9 | 0.14 |

| Viral enteropathy | 4 | 0.06 |

| Benign gastric epithelium-related changes | ||

| Focal gastric heterotopia | 104 | 1.66 |

| Gastric metaplasia | 48 | 0.77 |

| Duodenal mucosal surface changes | ||

| Ulceration | 25 | 0.40 |

| Lymphangiectasia | 25 | 0.40 |

| Erosion | 10 | 0.16 |

| Regenerative changes | 7 | 0.11 |

| Autoimmune/Inflammatory conditions | ||

| Crohn's disease | 5 | 0.08 |

| Drug-induced enteropathy | 5 | 0.08 |

| Lymphoid aggregates | 3 | 0.05 |

| Granuloma | 2 | 0.03 |

| Transplant-related diagnoses | ||

| Transplant | 20 | 0.32 |

| Graft versus host disease (GvHD) | 7 | 0.11 |

| Miscellaneous | 7 | 0.11 |

| Total | 6245 | 100 |

| Biopsy diagnostic category* | Clinical keywords |

| Adenoma | Gastrointestinal bleeding, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), polyp or papillary tumours on endoscopy |

| Amyloidosis | Systemic infiltrative disease |

| Carcinoma | Jaundice, gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel obstruction, mass or dilated bile duct on imaging or endoscopic examination, previous diagnosis of malignancy of any organ |

| Common variable immunodeficiency | Background of immunodeficiency syndrome, opportunistic infections (norovirus in our data) |

| Crohn’s disease | Previous diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, stricture, fistula |

| Drug induced enteropathy | Established autoimmune disease on immunomodulators/NSAIDs* |

| Flat (non-adenoma) dysplasia | Gastrointestinal bleeding, necrotic ulcer |

| Focal gastric heterotopia | Polyp on endoscopy |

| Gastric metaplasia | Polyp on endoscopy |

| Giardia | Iron deficiency anaemia, weight loss, abdominal pain |

| Granuloma | History of tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease |

| Hyperplasia without dysplasia | Polyp on endoscopy |

| Lipoma | Nodule on endoscopy |

| Lymphangiectasia | Gastrointestinal bleeding, ill-defined mass on endoscopy |

| Lymphoid aggregates | Mass on endoscopy |

| Lymphoma | Duodenal mass, gastrointestinal bleeding, previous diagnosis of lymphoma |

| Neuroendocrine tumour | Nodule/polyp |

| Ulceration | Gastrointestinal bleeding, abnormal barium study, relevant drug history (NSAIDs†) |

| Viral enteropathy | Immune suppression |

| Characteristic | Finding (n = 227) |

| Median age in years (standard deviation) | 49 (17.72) |

| Female sex (%) | 163 (71.81) |

| Male sex (%) | 64 (28.19) |

| Indications for biopsy (%) | |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | 108 (47.58) |

| Diarrhoea | 44 (19.38) |

| Abdominal pain | 32 (14.10) |

| Weight loss | 33 (14.54) |

| Dyspepsia | 24 (10.57) |

| Reflux | 16 (7.05) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 9 (3.96) |

| Folate deficiency | 9 (3.96) |

| Nonspecific altered bowel movements | 8 (3.52) |

| Dysphagia | 8 (3.52) |

| Bloating | 7 (3.08) |

| Constipation | 4 (1.76) |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | 4 (1.76) |

| No information provided | 23 (10.13) |

| Characteristic | Finding (n = 33) |

| Median age in years (standard deviation) | 48 (16.63) |

| Female sex (%) | 23 (69.70) |

| Male sex (%) | 10 (30.30) |

| Integrated clinical diagnosis of coeliac disease (%) | n=24 |

| Prior to biopsy | 9 (27.27) |

| Subsequent to biopsy | 13 (39.39) |

| After further biopsy | 2 (6.06) |

| Features strongly suspicious for coeliac disease (%) | n=9 |

| positive IgA(tTG) & positive EMA | 5 (15.15) |

| positive IgA(tTG) & negative/missing EMA | 4 (12.12) |

| Associated Condition | Number of Cases, n (%)(N = 227) | Prevalence in UK Population (from published studies) |

| Proton pump inhibitor use | 26 (11.45) | 18.04% [44] |

| NSAID1 use | 18 (7.93) | Variable [45] |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 12 (5.29) | Up to 35% [46] |

| Irritable bowel disease | 9 (3.96) | 10 – 20% [47] |

| Hypothyroidism | 8 (3.52) | 2% [48] |

| Graves’ disease | 6 (2.64) | 0.75% [49] |

| Microscopic colitis | 4 (1.76) | 0.1% [50] |

| Pernicious anaemia | 3 (1.32) | 0.05 – 0.2% [51] |

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (1.32) | 0.27% [52] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (1.32) | 1% [53] |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 3 (1.32) | 0.05 – 0.2% [54] |

| Gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma | 3 (1.32) | Variable [55,56] |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 (0.88) | 0.39% [52] |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathy | 2 (0.88) | 0.5 – 1.9% [57] |

| Addison’s disease | 2 (0.88) | 0.01% [58] |

| Transplanted ileum and colon | 1 (0.44) | 19 cases in 2018-19 [59] |

| Duodenal neuroendocrine tumour | 1 (0.44) | 0.00017% [60] |

| Abnormal Laboratory Test | Number of Cases, n |

| Elevated faecal calprotectin | 37 |

| Elevated ESR1 | 17 |

| Elevated CRP2 | 15 |

| IgA3 deficiency | 10 |

| Elevated ANA4 | 8 |

| Elevated rheumatoid factor | 7 |

| Elevated p-ANCA5 | 3 |

| Elevated anti-cyclic citrullinated protein | 2 |

| Elevated c-ANCA | 1 |

| Elevated anti-U1 RNP6 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).