Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

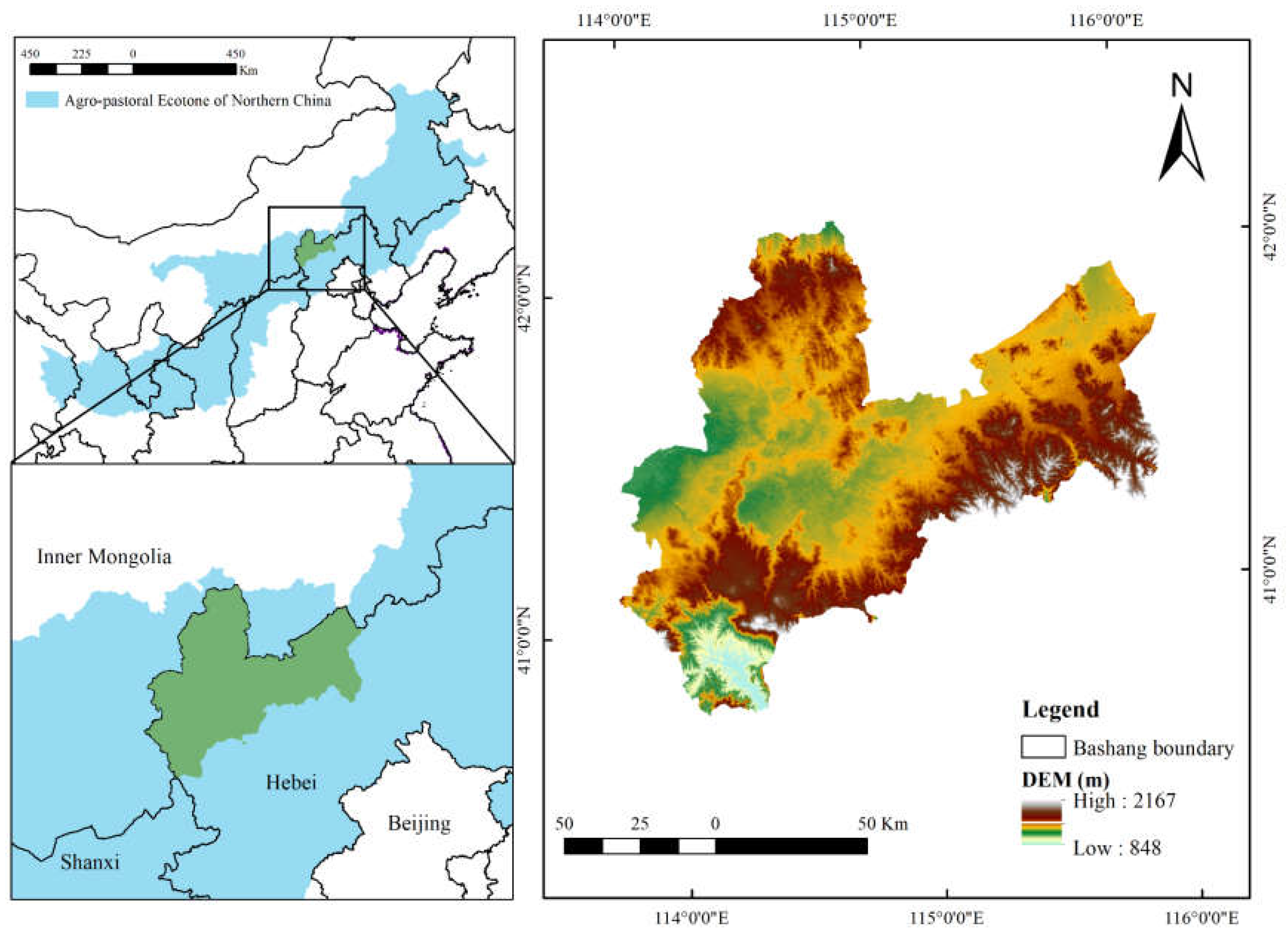

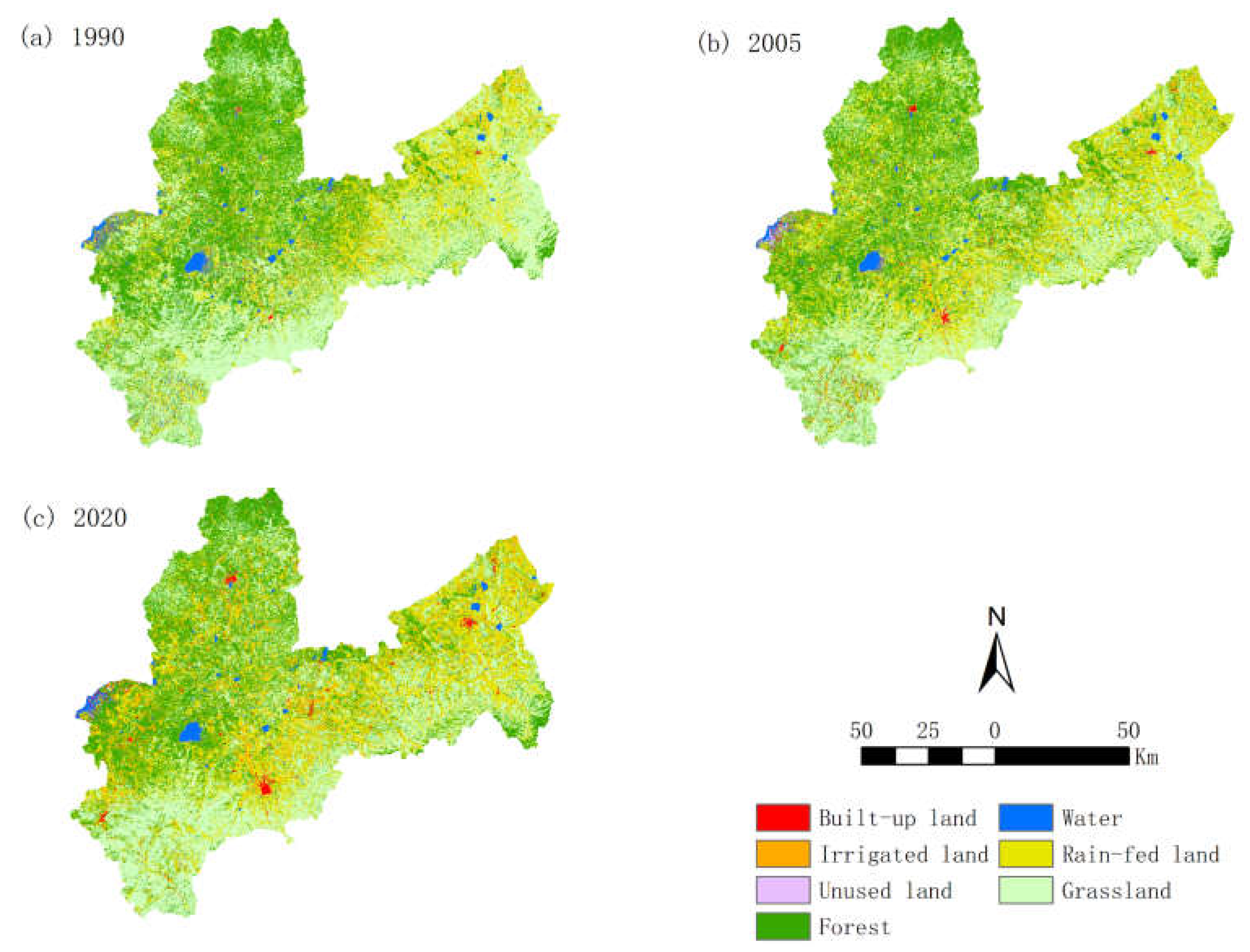

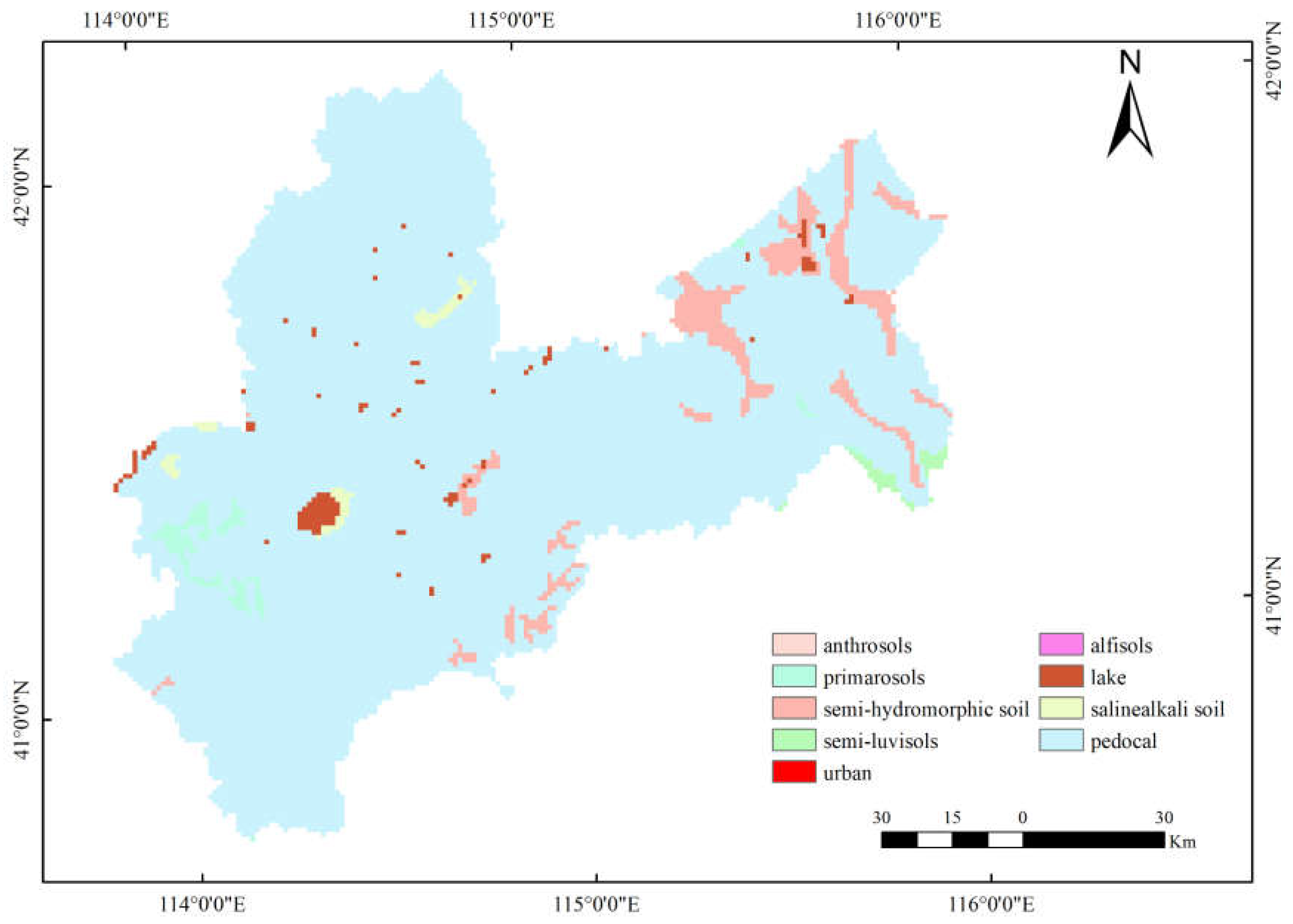

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Land Use Change Analysis and Multiscenarios Prediction

2.3.1. Geoinformation Tupu Model Analysis

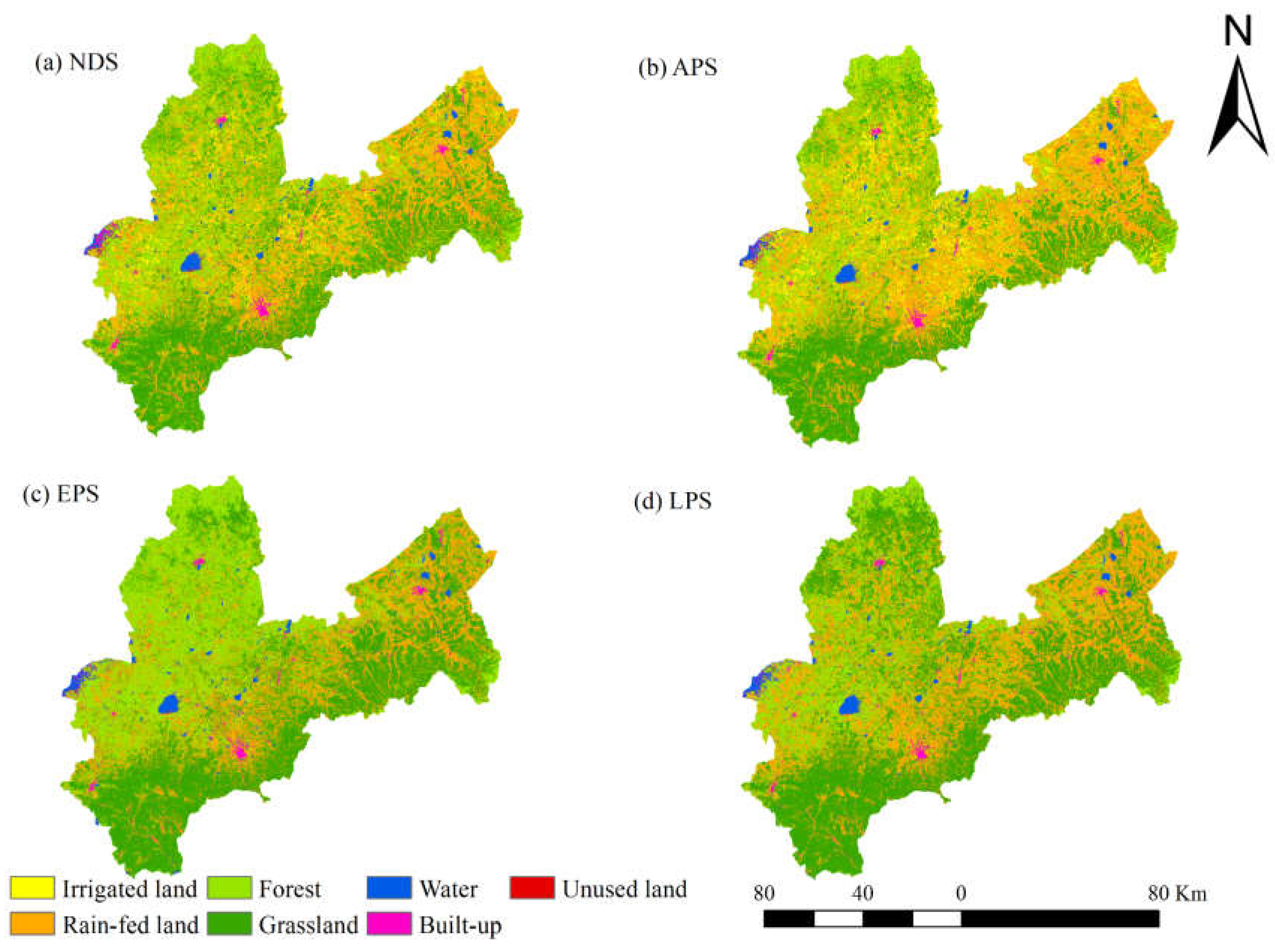

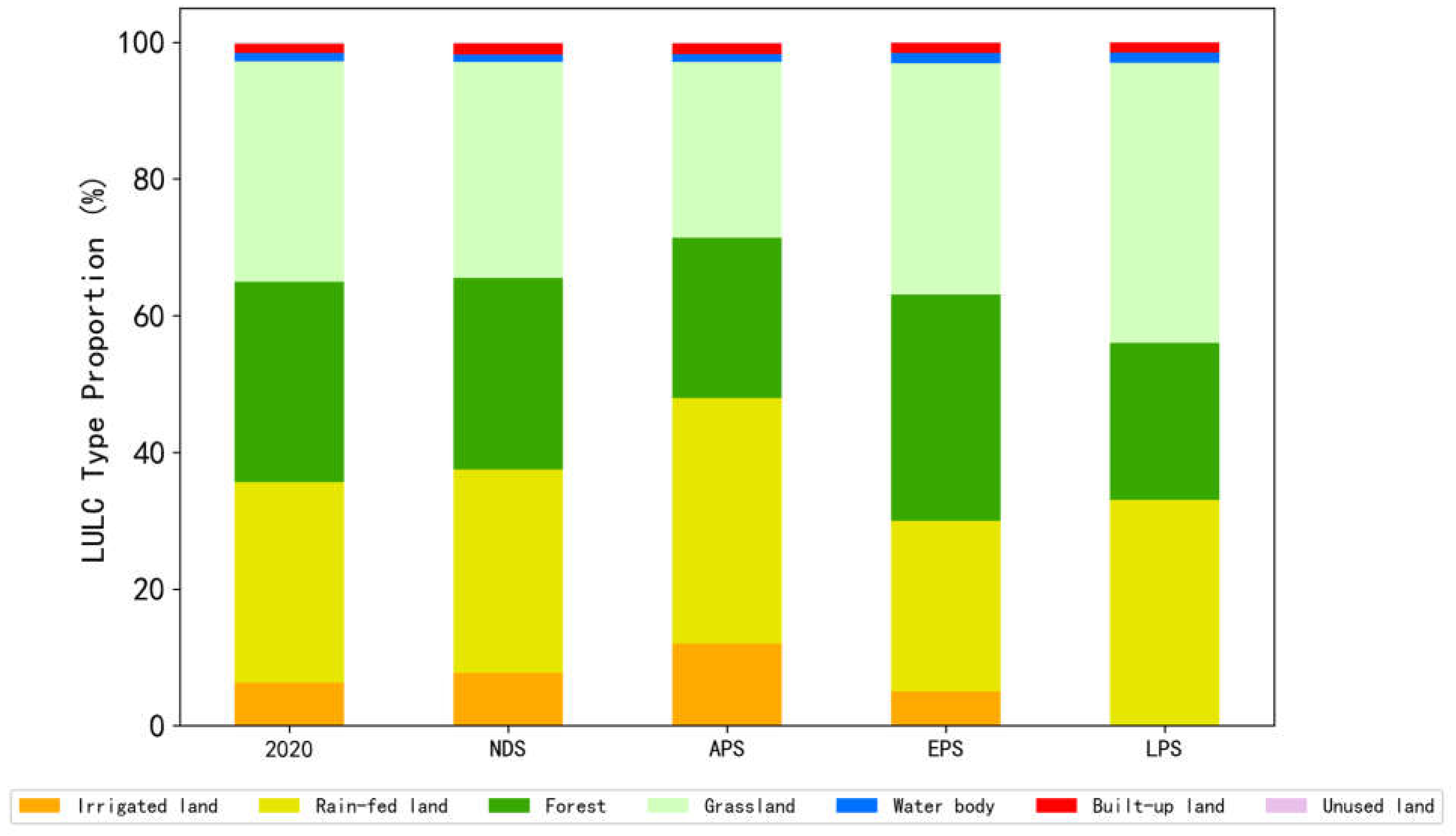

2.3.2. Multi-Scenarios Setting

- NDS (Natural Development Scenario): This scenario excludes the influence of anthropogenic and socio-environmental factors. It forecasts land-use changes for 2035, relying exclusively on the natural trends in land-use transformation observed between 1990 and 2020.

- APS (Agricultural Production Scenario): In this scenario, the study region simulates the maximum extent of arable land expansion under an agricultural development objective. Specifically, the conversion of unutilized land, forest and grassland into arable land is promoted while ensuring that existing arable land (both irrigated and rain-fed land) remains unchanged. Therefore, in the configuration of neighborhood weights, the transition probability for irrigated land and rain-fed land were increased by 30%. Prohibitions were imposed on the conversion of cultivated to other types.

- EPS (Ecological protection Scenario): This scenario incorporates ecological conservation objectives for the study area. The study proposes simulating the maximized expansion of ecological lands, particularly forest and grassland. The framework emphasizes the dual imperatives of protecting and enhancing ecological land resources. Under this configuration: (1) Strict prohibitions were instituted against conversions of forest and grassland to other types and transformations of unutilized land to cultivated areas; (2) Transition from rain-fed land to irrigated land was restricted; (3) Neighborhood weights underwent strategic adjustments—irrigated land weights decreased by 50%, rain-fed land weights reduced by 20%, while grassland and woodland weights increased by 40%.

- LPS (Land Planning Scenario): According to the Zhangjiakou Capital Water Conservation Functional Area and Ecological Environment Support Area Construction Plan (2019-2035), the objectives for 2035 are set as follows: The Bashang region of Zhangjiakou will progressively transition irrigated land to alternative land uses while restoring abandoned land through grass planting. Additionally, as stipulated in the Land Use Master Plan for Four Counties in the Bashang Region of Zhangjiakou (2021-2035), the permanent basic farmland area in Zhangjiakou Bashang is designated as 4,551.26 km². Based on these planning targets, the LPS is defined as follows: (1) Full conversion of irrigated to rain-fed land and strictly prohibit the transformation of other land categories into irrigated land; (2) Reduce the transition probability of irrigated land by 50%, while increasing the transition probability of forestland and grassland by 20% and 40%, respectively; (3) Ensure cultivated land area remains within the protection red line for basic farmland; (4) Strictly prohibit the conversion of forestland and grassland to other categories.

2.3.3. The FLUS Model

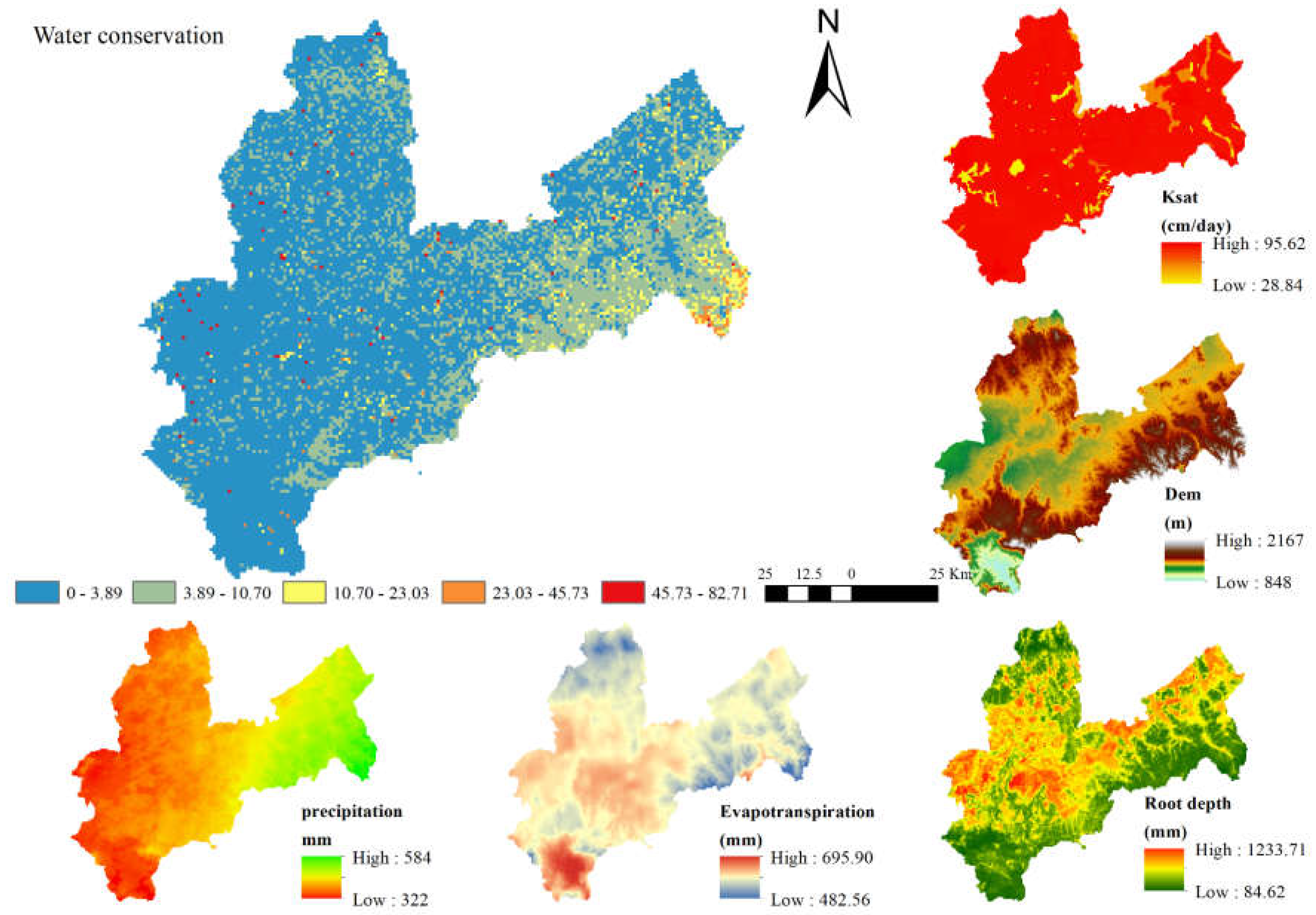

2.4. Water Conservation Assessment

2.4.1. The InVEST Water Yield Model

2.4.2. Calculation Method of Water Conservation

2.4.3. Validation of InVEST Model Accuracy

3. Results

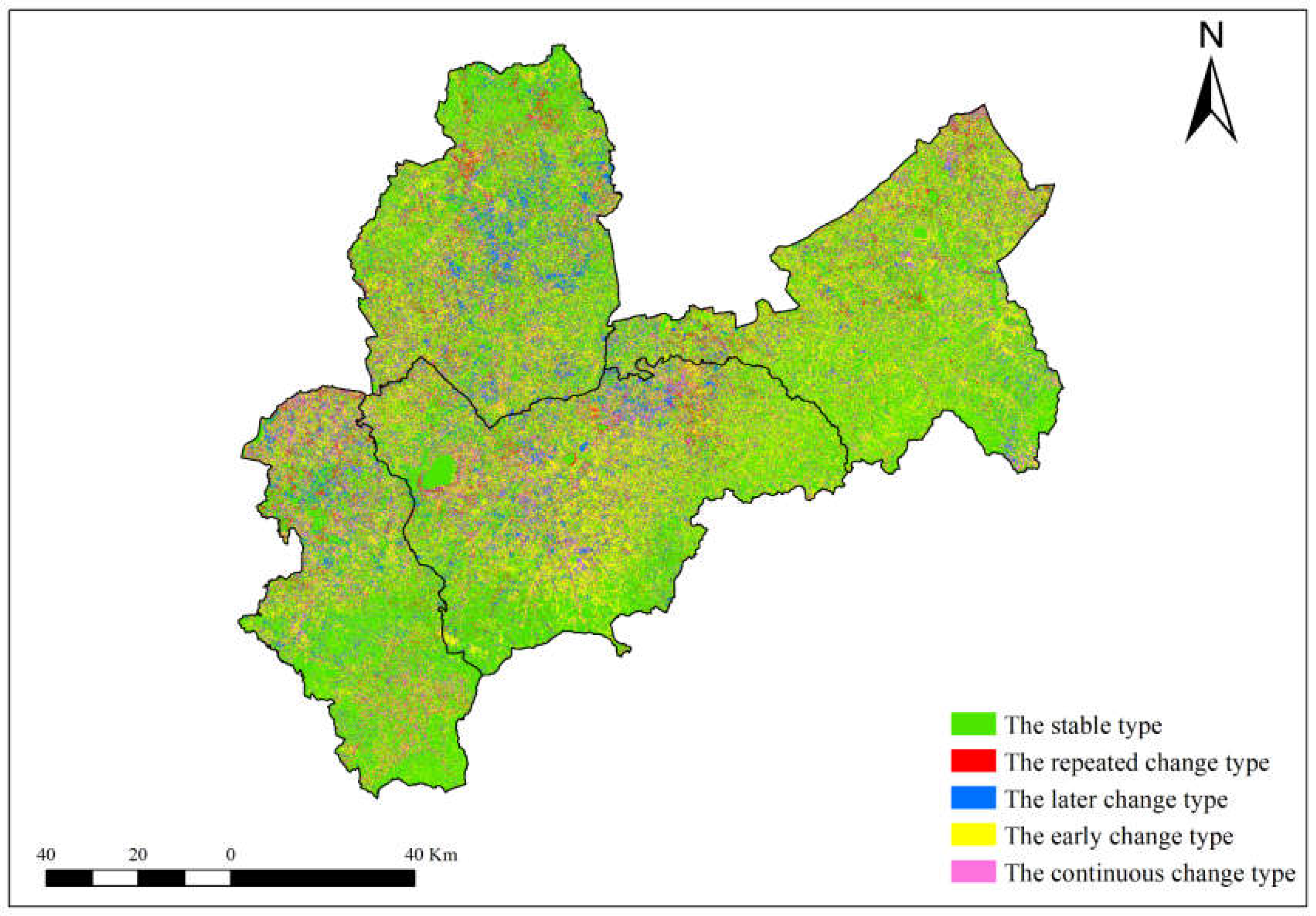

3.1. Geoinformation Tupu of LULC

3.2. Multi-Scenario LULC Simulation

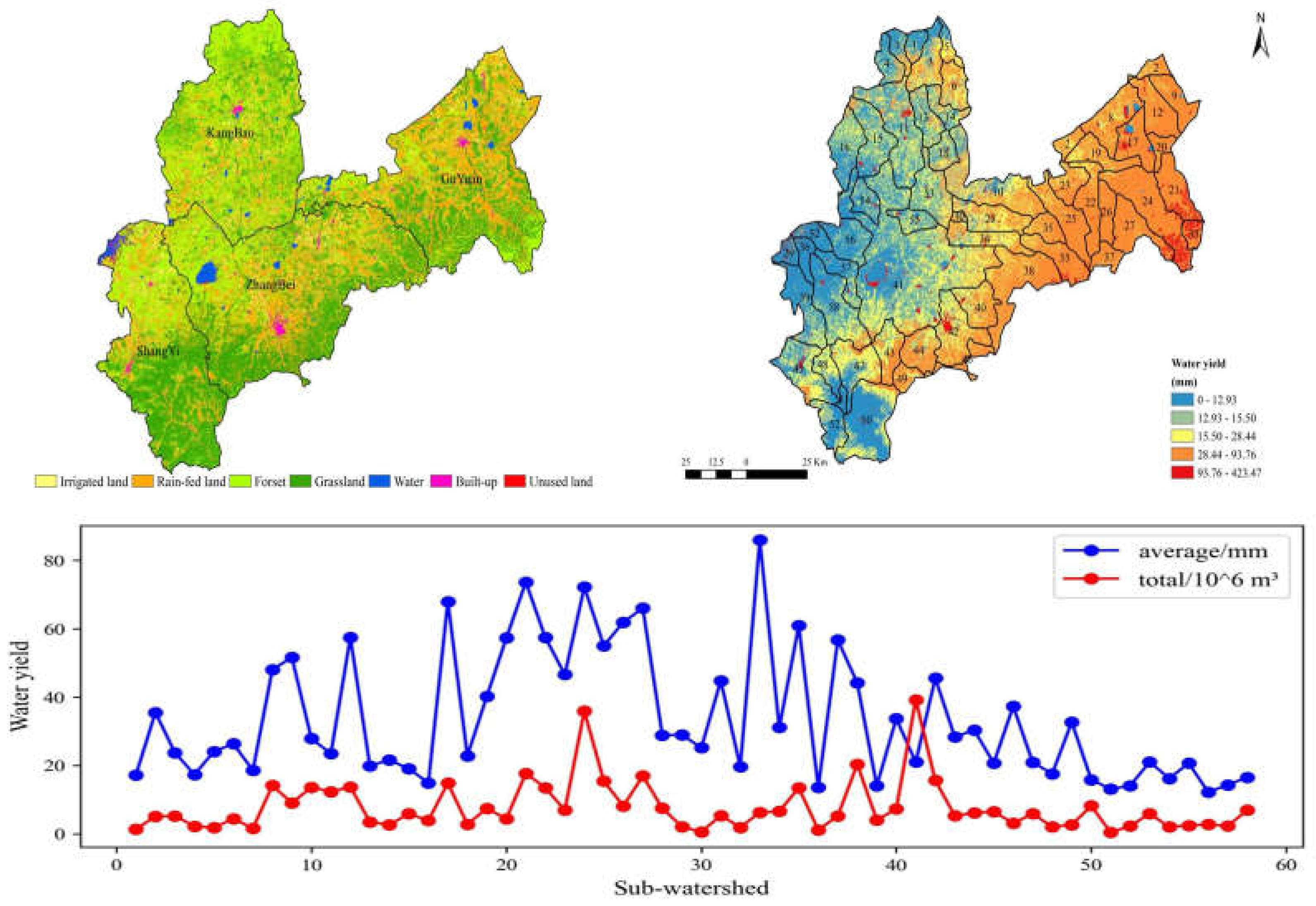

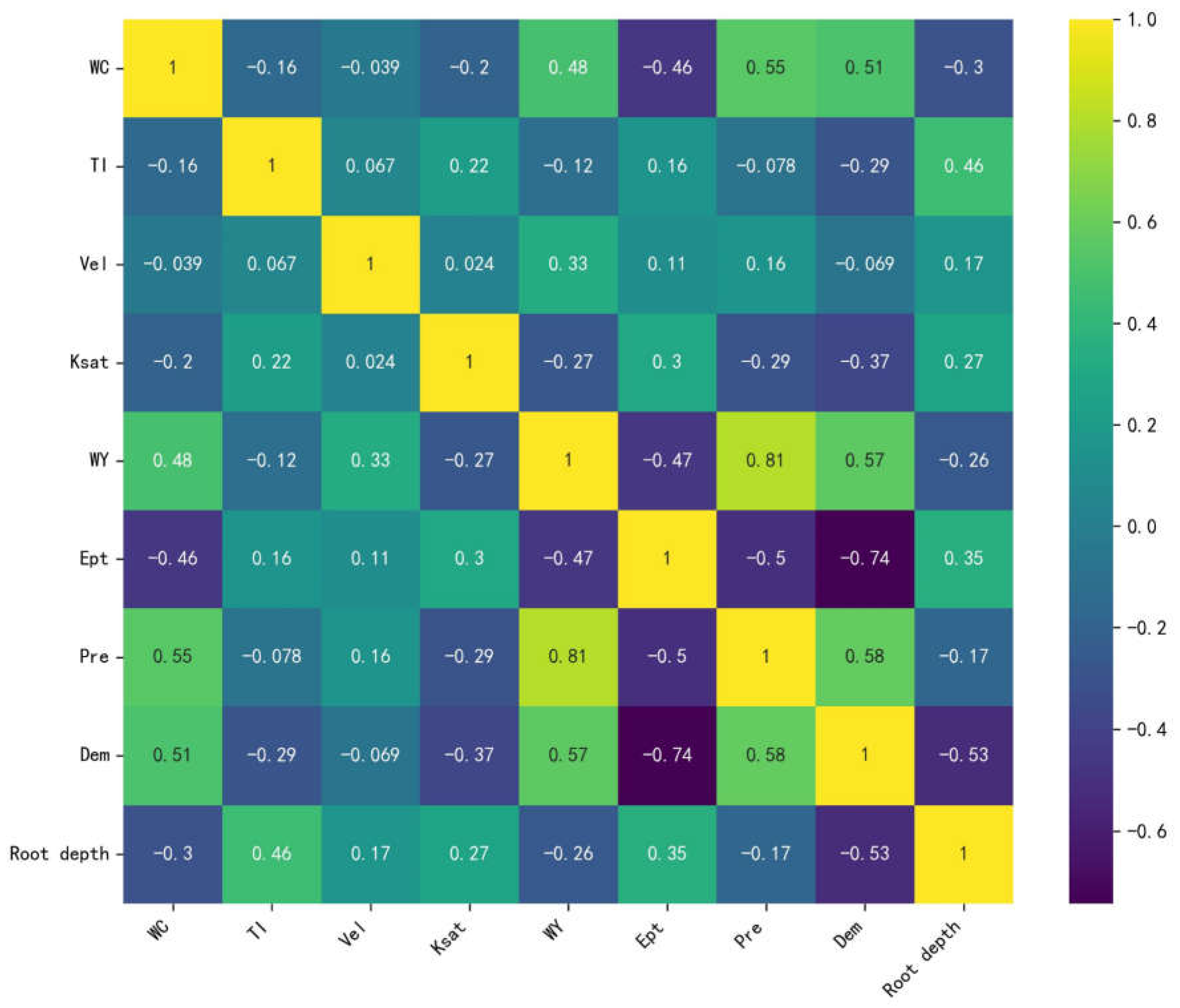

3.3. Evaluation of Water Conservation Based on InVEST and Main Driver Analysis

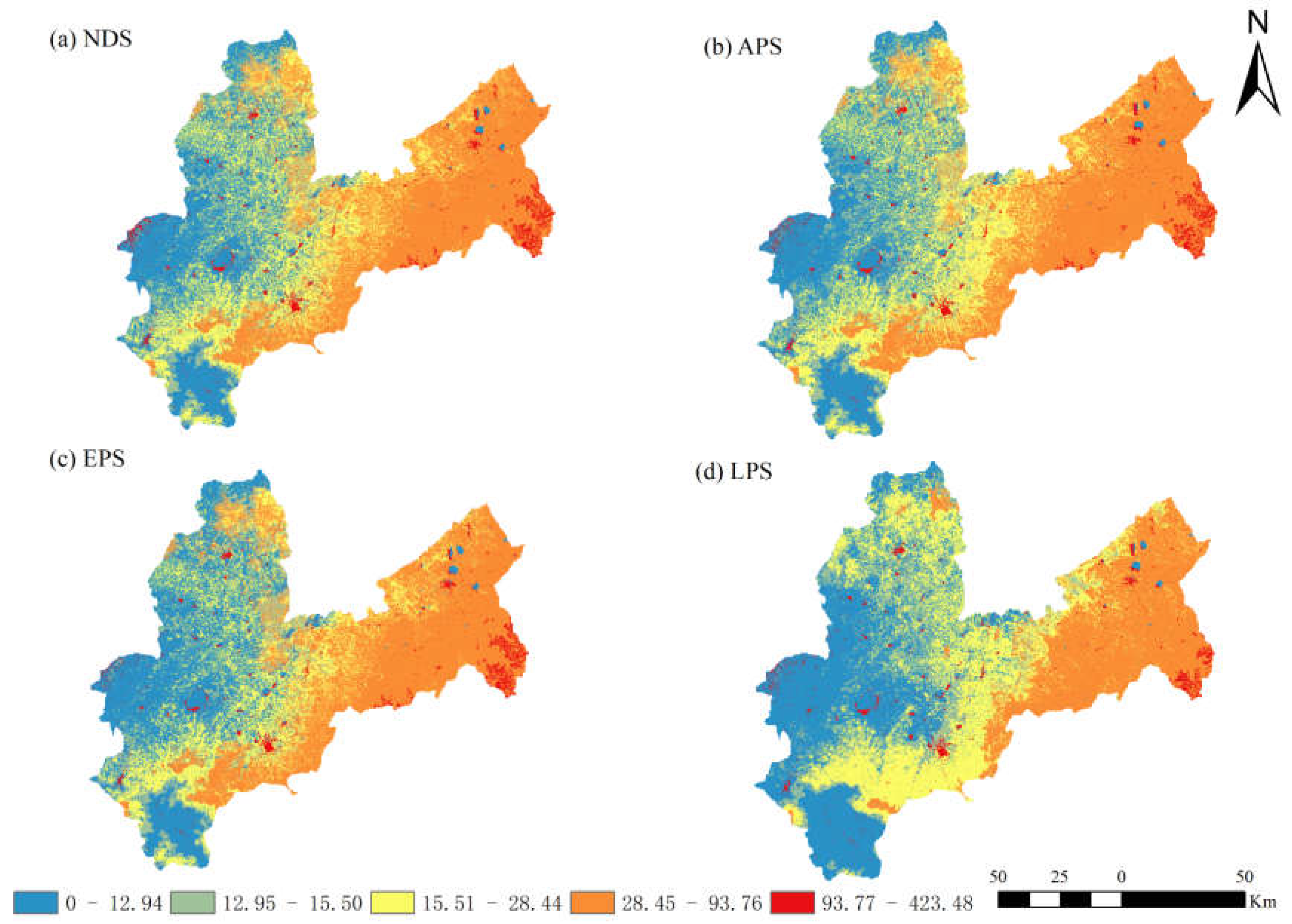

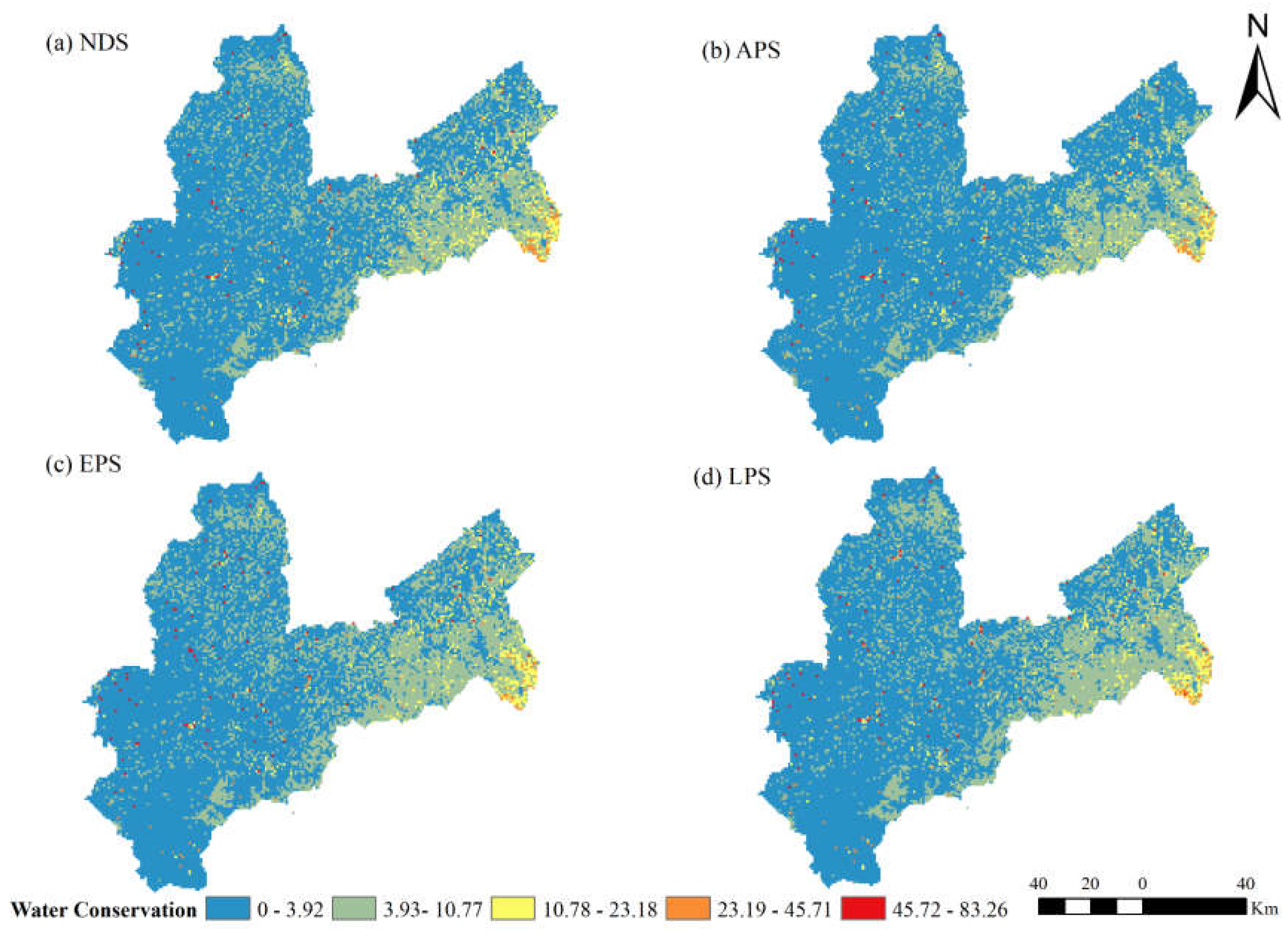

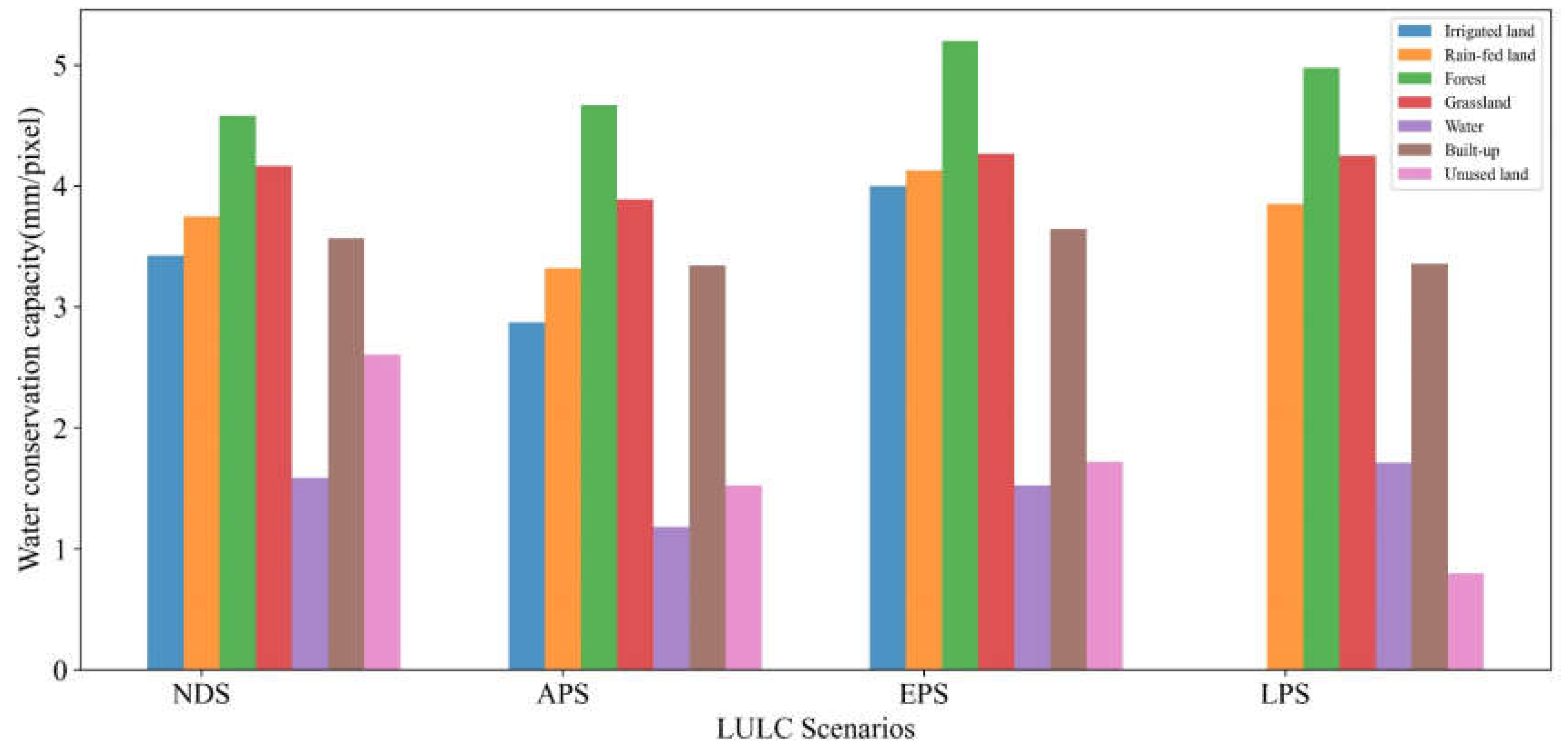

3.4. Multi-Scenario Water Conservation Simulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of LULC on Water Conservation Function

4.2. Climate Impacts on WCC

4.3. Limitations and Future Works

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WY | Water Yield |

| WCC | Water Conservation Capacity |

| LULC | Land Use / Land Cover |

References

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, J.; Bryan, B.A. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nature communications 2021, 12, 4667–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boretti, A.; Rosa, L. Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. npj Clean Water 2019, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Chiarelli, D.D.; Rulli, M.C.; Dell’Angelo, J.; D’Odorico, P. Global agricultural economic water scarcity. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaaz6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.; Fuchs, R.; Rounsevell, M.; Herold, M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Yu, C.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Impacts of climate and land-use changes on water yields: Similarities and differences among typical watersheds distributed throughout China. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Evaluating potential impacts of land use changes on water supply–demand under multiple development scenarios in dryland region. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, F.; Wu, J.; Gong, S.; Che, H.; et al. Analysis of the spatiotemporal changes in global land cover from 2001 to 2020. Science of the total environment 2023, 908, 168354–168354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Néstor, M.; Ximena, Q.; María, J.; Paúl, C. What Do We Know about Water Scarcity in Semi-Arid Zones? A Global Analysis and Research Trends. Water 2022, 14, 2685–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shen, Y.J.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Pei, H. The Impacts of Land Use Changes on Water Yield and Water Conservation Services in Zhangjiakou, Beijing’s Upstream Watershed, China. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measho, S.; Chen, B.; Pellikka, P.; Trisurat, Y.; Guo, L.; Sun, S.; Zhang, H. Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Associated Impacts on Water Yield Availability and Variations in the Mereb-Gash River Basin in the Horn of Africa. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2020, 125, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Liang, D.; Xia, J.; Song, J.X.; Cheng, D.D.; Wu, J.T.; Cao, Y.L.; Sun, H.T.; Li, Q. Evaluation of water conservation function of Danjiang River Basin in Qinling Mountains, China based on InVEST model. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 286, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldesenbet, T.A.; Elagib, N.A.; Ribbe, L.; Heinrich, J. Hydrological responses to land use/cover changes in the source region of the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 575, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Zuo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sun, F.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y. Impact of Land Use Change on Water Conservation: A Case Study of Zhangjiakou in Yongding River. Sustainability 2020, 13, 22–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, F.; Gao, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X. The impact of land-use change on water-related ecosystem services: a study of the Guishui River Basin, Beijing, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 163, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshi, A.; Brouwer, R.; Najafinejad, A.; Panahi, M.; Zarandian, A.; Maghsood, F.F. Modelling the impacts of climate and land use change on water security in a semi-arid forested watershed using InVEST. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 593, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Q.; Yang, H.C.; Wang, L.J.; Xu, Z.X.; Xue, B.L. Using the SWAT model to assess impacts of land use changes on runoff generation in headwaters. Hydrological Processes 2014, 28, 1032–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Di, Z.; Yao, Y.; Ma, Q. Variations in water conservation function and attributions in the Three-River Source Region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on the SWAT model. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2024, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Xu, Z.; Han, Y.; Peng, D.; Pang, B.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Yang, H. Assessment of changes in water conservation capacity under land degradation neutrality effects in a typical watershed of Yellow River Basin, China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balist, J.; Malekmohammadi, B.; Jafari, H.R.; Nohegar, A.; Geneletti, D. Detecting land use and climate impacts on water yield ecosystem service in arid and semi-arid areas. A study in Sirvan River Basin-Iran. Applied Water Science 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayitesi, N.M.; Guzha, A.C.; Tonini, M.; Mariethoz, G. Land use land cover change in the African Great Lakes Region: a spatial-temporal analysis and future predictions. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2024, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Nelson, E.; Plantinga, A.J.; Lewis, D.J.; Helmers, D.; Lawler, J.J.; Withey, J.C.; Beaudry, F.; Martinuzzi, S.; Butsic, V.; et al. Economic-based projections of future land use in the conterminous United States under alternative policy scenarios. Ecological Applications 2012, 22, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.C.; Jing, Y.D.; Han, S.M. Multi-scenario simulation of land use/land cover change and water yield evaluation coupled with the GMOP-PLUS-InVEST model: A case study of the Nansi Lake Basin in China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 155, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichao, L.; Jianhua, W.; Fei, X.; Dawei, M.; Pengbin, Z. Modeling the effects of land use/land cover changes on river runoff using SWAT models: A case study of the Danjiang River source area, China. Environmental research 2023, 242, 117810–117810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlhodi, B.; K. , K.P.; P., P.B.; G., M.J. Analysis of the Future Land Use Land Cover Changes in the Gaborone Dam Catchment Using CA-Markov Model: Implications on Water Resources. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2427–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guan, Q.; Sun, Y.; Du, Q.; Xiao, X.; Luo, H.; Zhang, J.; Mi, J. Simulation of future land use/cover change (LUCC) in typical watersheds of arid regions under multiple scenarios. Journal of environmental management 2023, 335, 117543–117543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.P.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.C.; Ou, J.P.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, S.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Pei, F.S. A future land use simulation model (FLUS) for simulating multiple land use scenarios by coupling human and natural effects. Landscape and Urban Planning 2017, 168, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Feng, K.; Sun, L.; Zhao, D.; Huang, X.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Baiocchi, G. Rising agricultural water scarcity in China is driven by expansion of irrigated cropland in water scarce regions. One Earth 2022, 5, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Rosa, L.; Daily, G. Global expansion of sustainable irrigation limited by water storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2022, 119, e2214291119–e2214291119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Yan, J.; Sha, J.; He, G.; Lin, X.; Ma, Y. Dynamic modeling application for simulating optimal policies on water conservation in Zhangjiakou City, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 201, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Jun, X. Hydrological cycle and water resources in a changing world: A review. Geography and Sustainability 2021, 2, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.X.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.L.; Yang, J. Sustainable management of land use patterns and water allocation for coordinated multidimensional development. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 457, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.Y.; Mao, M.J.; Zhao, Y.X.; Wu, G.H.; Wang, H.B.; Li, M.H.; Liu, T.D.; Wei, Y.H.; Huang, S.R.; Huang, L.Y.; et al. Spatio-temporal characteristics and multi-scenario simulation analysis of ecosystem service value in coastal wetland: A case study of the coastal zone of Hainan Island, China. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 368, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S.; Jin, H.; Xia, X. Geo-informatic spectrum analysis of land use change in the Manas River Basin, China during 1975-2015. The Journal of Applied Ecology 2019, 30, 3863–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, E.; Zhu, H. An ecological-living-industrial land classification system and its spatial distribution in China. Resources Science 2015, 37, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.T.; Zhai, S.Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Wang, Z. Multi-scenario simulation of production-living-ecological space and ecological effects based on shared socioeconomic pathways in Zhengzhou, China. Ecological Indicators 2022, 137, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.C.; Sun, X.Y.; Guo, H.; Shan, R.F. Comparison of the SWAT and InVEST models to determine hydrological ecosystem service spatial patterns, priorities and trade-offs in a complex basin. Ecological Indicators 2020, 112, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hickel, K.; Dawes, W.R.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Western, A.W.; Briggs, P.R. A rational function approach for estimating mean annual evapotranspiration. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, R.J.; Roderick, M.L.; McVicar, T.R. Roots, storms and soil pores: Incorporating key ecohydrological processes into Budyko’s hydrological model. Journal of Hydrology 2012, 436, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Li, Z.X.; Feng, Q.; Gui, J.; Zhang, B.J. Spatiotemporal variations of water conservation and its influencing factors in ecological barrier region, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Hydrol.-Reg. Stud. 2022, 42, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.X.; Lyu, Y.H.; Fu, B.J.; Hu, J. Hydrological services by mountain ecosystems in Qilian Mountain of China: A review. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Cao, G.C.; Cao, S.K.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, M.L.; Tong, S.; Li, H.D. Spatiotemporal variations of water conservation and its influencing factors in the Qinghai Plateau, China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 155, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.M.; Li, G.; Li, Z.N. Spatial and temporal evolution characteristics of the water conservation function and its driving factors in regional lake wetlands-Two types of homogeneous lakes as examples. Ecological Indicators 2021, 130, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.I.; Roebeling, P.C.; Alves, F.L.; Villasante, S.; Magalhaes, L. High risk water pollution hazards affecting Aveiro coastal lagoon (Portugal)-A habitat risk assessment using InVEST. EcologicalInformatics 2023, 76, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.X.; Yang, H.; Zhou, H.T.; Wang, H.X. Synergistic changes in river-lake runoff systems in the Yangtze River basin and their driving force differences. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shu, Z.; Yang, F.; Fu, D.; Ma, L.; Zhang, L.; Xue, Y. Temporal and spatial variation characteristics of water conservationfunction of Upper Danjiang River Basin in Qinling Mountains and itsinfluencing factors. Coal Geology & Exploration 2023, 51, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, B.A.; Gao, L.; Ye, Y.Q.; Sun, X.F.; Connor, J.D.; Crossman, N.D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Wu, J.G.; He, C.Y.; Yu, D.Y.; et al. China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 2018, 559, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Name | Data Source |

| LULC data | LULC from 1990 to 2020 | Resources and environment science data platform https://www.resdc.cn/ |

| Natural environment | Elevation | Geospatial data cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn) |

| Slope | Extraction from elevation | |

| Aspect | ||

| Average monthly temperature | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center | |

| Average monthly precipitation | ||

| Potential evapotranspiration | ||

| Percentages of sand, clay, silt and organic carbon | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, https://www.fao.org/) | |

| Soil Type | Resources and environment science data platform (https://www.resdc.cn/) | |

| Accessibility factors | Distance from main | Geospatial data cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn) |

| road, distance from | ||

| main railway | ||

| Socioeconomic | Population density, | Resources and environment science data platform (https://www.resdc.cn/) |

| gross domestic product | ||

| (GDP) |

| LULC | LULC_veg | Root_depth | Kc |

| Irrigated land | 1 | 300 | 0.954 |

| Rain-fed land | 1 | 300 | 0.865 |

| Forest | 1 | 3500 | 1.009 |

| Grassland | 1 | 500 | 0.8 |

| Water area | 0 | 0 | 1.05 |

| Built-up land | 0 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Unused land | 0 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Geoinformation Tupu Type | Area/Km² | Proportion | Characteristics |

| The stable type | 6023.9727 | 43.78% | The LULC remained unchanged from 1990-2020 |

| The continuous-change type | 1334.3436 | 9.70% | The LULC changed in 1990-2005/2005-2020 without repeated types |

| The repeated-change type | 943.029 | 6.85% | The LULC changed in the early stages as opposed to the later stages |

| The later-change type | 1628.1585 | 11.83% | The LULC changed in the period of 2005-2020 |

| The early-change type | 3828.9078 | 27.83% | The LULC changed from 1990 to 2005 but did not change from 2005 to 2020 |

| Scenario | Water Yield | Water Conservation Capacity | ||

| Mean(mm/pixel) | Total(106 m3) | Mean(mm/pixel) | Total(106 m3) | |

| 2020 | 32.720 | 446.063 | 3.820 | 27.027 |

| 2035 NDS | 33.362 | 454.808 | 3.801 | 26.556 |

| 2035 APS | 32.885 | 448.317 | 3.418 | 24.031 |

| 2035 EPS | 32.714 | 446.328 | 3.875 | 28.464 |

| 2035 LPS | 35.066 | 478.092 | 3.990 | 27.701 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).