1. Introduction

The endometrium is a unique tissue that plays an important role in reproduction. Its functional transformation throughout the menstrual cycle provides optimal conditions for embryo implantation. This process includes several critical stages: primary contact with the endometrium, introduction into the stroma, and maintenance of trophoblast invasion [

1,

2,

3]. Successful completion of these stages depends on a strictly regulated uterine microheart, in which the extracellular matrix acts as a key modulator. The endometrial extracellular matrix is a dynamic structure that forms a mechanical and biochemical environment for cellular adhesion, migration, and differentiation [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Among its components, collagen plays a special role, determining its biomechanical properties [

8,

9,

10]. Collagen I forms strong fibrils that increase tissue rigidity, reticulin is characterized by increased elasticity and immaturity of the structure. The balance between these collagen types is important for the regulation of tissue stiffness and the stability of the extracellular matrix structure [

11,

12,

13]. In addition, collagen affects a wide range of cellular processes, including cell migration and differentiation, as well as limiting excessive trophoblast invasion [

14,

15,

16].

Scientific studies show that changes in collagen expression in the endometrium are associated with reproductive losses, including implantation failures [

17,

18,

19,

20]. These changes can also disrupt the process of transformation of stromal fibroblasts into the decidual phenotype - a key stage of successful implantation [

21,

22,

23]. Immunological, transcriptomic and proteomic studies have shown that the endometrium in miscarriage and infertility has structural and functional abnormalities compared to normally functioning endometrium at the same stage of the menstrual cycle [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Furthermore, accumulating data indicate that changes in the endometrial microenvironment include increased activity of matrix metalloproteinases leading to excessive collagen degradation [

24,

32]. Such structural and molecular changes contribute to the maintenance and prolongation of adverse changes, which may lead to persistent changes in the extracellular matrix.

Despite significant advances in the study of the endometrial extracellular matrix, the identification of its microstructural histochemical features remains a challenge in routine clinical practice. Traditional diagnostic methods such as ultrasonography and standard histology have limited sensitivity for detecting microstructural changes in the extracellular matrix in reproductive dysfunction. The present study aims to fill one aspect of this gap. We describe histochemical patterns of the extracellular matrix with an assessment of the distribution of reticulin and collagen in midsecretory phase endometrial biopsies. By comparing the reticulin-collagen histochemical pattern in women with physiological reproductive status and in women with recurrent reproductive losses, we present evidence for the utility of this diagnostic approach for stratifying women at risk of reproductive failure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Here we present cross-blind research conducted by comparing the histochemical pattern of the endometrium with ultrasound characteristics and the results of a standard histological examination of the endometrium of the middle stage of the secretion phase in groups of fertile women with physiological reproductive status and recrudescent reproductive failures. Patients were recruited between January and May 2024. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before endometrial sampling. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Local Bioethics Commission of the NCJSC “Karaganda Medical University” (Protocol No. 1 of 29.12.2023).

We formed two groups to study the histochemical pattern of the endometrium:

The group of women with physiological reproductive status (group 1) consisted of fertile women with at least two pregnancies with a live fetus delivery in the anamnesis (the number of pregnancies was equal to the number of births).

The group of women with recrudescent reproductive failures (group 2) consisted of fertile women with at least two clinical or biochemical pregnancy losses or at least two unsuccessful cycles of extracorporal fertilization with embryos of good quality.

Clinical data were obtained from medical records in a complex medical information system.

Exclusion criteria: (1) women under 20 years of age or over 40 years of age, body mass index (BMI) >29.9 kg/m2; (2) congenital uterine abnormalities or acquired uterine diseases, including endometrial polyps, submucous myomas, uterine synechias, and adenomyosis; (3) chronic endometritis; (4) hydrosalpinx; (5) positive antibodies to lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin; (6) gynecological operations in the preceding two months, intrauterine device or any form of hormonal contraception during the six months preceding the study; (7) genetic abnormalities of the fetus; (8) elevated or decreased levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) or luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol (E2) (9) polycystic ovary syndrome.

In our study, the physiological reproductive status was defined as the ability to achieve clinical pregnancy without assisted reproductive technologies and with a live fetus delivery.

In our study, reproductive failure was defined as the absence of pregnancies (infertility 1 or infertility 2 type) or spontaneous termination of clinical pregnancy (loss of pregnancy after spontaneous conception, assisted reproductive technologies, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole) or biochemical pregnancy (failure of implantation).

Biochemical pregnancy is a pregnancy diagnosed based on a set of signs: (1) β-HCG (<100 mlU/ml); (2) a rapid drop in the concentration of β-HCG in urine or serum [

33].

Clinical pregnancy is a pregnancy diagnosed by ultrasound imaging of one or more intrauterine embryos or obvious clinical signs of intrauterine pregnancy [

33].

Stimulated cycles (SC) is a pharmacological therapy in a woman to form regular ovulatory cycles [

34].

Natural cycles (NC) are menstrual cycles without pharmacological drug usage [

34].

Assisted reproductive technologies involve in vitro processing of human oocytes and spermatozoa or embryos for reproduction [

33].

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

The formula for comparing two independent proportions was used to calculate the sample size, assuming a significance level of 5% and a test power of 80%. The initial proportions for the two groups were p1 = 0.70 (physiological reproductive status group) and p2 = 0.40 (recurrent reproductive loss group), based on the results of the preliminary analysis of our pilot study, which resulted in an estimated sample size of 40 participants in each group. To account for possible dropouts or exclusions, the sample was increased by 20%, after which the result was rounded to the nearest ten. As a result, the total sample size was 100 participants, equally distributed between the two groups.

The sample size calculation was performed using standard statistical methods [

35] and verified using G*Power software, version 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany) [

36].

2.3. Methodology of Ultrasound Assessment of the Endometrium

A General Electric Voluson E8 ultrasound system with a 2D vaginal sensor with a 5-8 MHz frequency was used for ultrasonography examination. All ultrasonography studies were conducted by the same doctor using the same ultrasound device.

Transvaginal ultrasonography was performed in the morning before the endometrial biopsy. The estimated parameters included the thickness of the endometrium [

37,

38,

39,

40], the homogeneity/heterogeneity of the echo of the functional layer of the endometrium [

37,

38,

40,

41] with the presence/absence of a central echogenic line of the endometrium [

42] according to the approved protocol.

The thickness of the endometrium was evaluated as the distance between the border of the endometrium and the myometrium of the anterior and posterior walls of the uterus, measured at a distance of 2 cm from the uterine fundus in the projection of the median longitudinal axis of the uterus. The measurement was carried out three times, and the average value was calculated. Images of the endometrium in the longitudinal direction were taken on the 21st day of the cycle. Clinicians examined the pattern and thickness of the endometrium on the day of the examination. After that, two researchers re-evaluated the endometrial echo simultaneously to assess the homogeneity and visibility of the median line.

The ultrasound pattern corresponding to the endometrium of the secretion phase was considered an echogenic endometrium [

43] with a thickness of more than 7 mm [

44,

45,

46].

2.4. Methods of Endometrial Biopsy Sampling and Their Histological Examination

All endometrial biopsies were taken on the 21st day of the cycle, on an outpatient basis, using a suction curette (Pipelle de Cornier, Prodimed, Neuillyen Thelle, France). Biopsies were taken from the fundus and upper part of the anterior and posterior walls of the uterus to assess the zones of maximum physiological development [

47].

After fixation with 10% formalin at 4 °C for 24 hours, sections with a thickness of 5 microns were stained at room temperature according to standard protocols with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson trichrome [

48] and Gomori’s silver plating [

49].

Morphometric analysis of histological preparations was carried out blindly by two independent pathologists. In case of disagreement, a consensus diagnosis was made.

The main morphometric measurements and photographs were carried out using a light microscope and digital color microphotography with «Image» software. The material with an area of more than 1 cm2 was considered a sufficient volume for the study.

Histological examination was performed according to a standard established protocol (Mayer’s hematoxylin, Bio-Optica (Italy)).

2.4.1. Glandular Epithelium

The pattern of the glandular epithelium of the endometrium was evaluated using established criteria [

50,

51]. When dating the endometrium, the days of the menstrual cycle and histological dating criteria were considered [

50,

52]. The histological diagnosis of the glandular epithelium pattern mismatch of the middle stage of secretion was defined as the asynchronous development of the glands with a delay/advance of the cycle day of more than 3 days [

53].

2.4.2. Pinopods

Pinopods are cytoplasmic evagination of the apical surface of the cytosolic membrane of the glandular epithelium of the endometrium [

54,

55,

56,

57].

According to the relative number of pinopods, the micropreparations were divided into two subgroups:

- numerous, densely packed microvilli occupying most (>50%) of the apical membrane of epithelial cells;

- few rare microvilli occupying less than half (<50%) of the apical membrane of epithelial cells [

56].

Histochemical evaluation of the endometrial extracellular matrix by the reticulin-collagen pattern

A histochemical examination was carried out to evaluate the extracellular matrix of the endometrium according to the «reticulin-collagen» phenotype.

2.4.3. Reticulin Fibers of the Extracellular Matrix

The histochemical examination was carried out by Gomori’s silver plating (a kit of Reticulum stains (modified Gomori’s) (ab236473), Bio-Optica (Italy)) according to the standard research protocol. Reticulin fibers were defined as black or dark brown fibers with gray nuclei.

2.4.4. Collagen Fibers of the Extracellular Matrix

The histochemical examination was carried out by staining (Trichrome Stain Kit (Connective Tissue Stain) (ab150686), Bio-Optica (Italy)) according to the standard research protocol. Collagen fibers were defined as dark blue fibers with black nuclei.

2.4.5. Interpretation of the Histochemical Pattern of the Extracellular Matrix of the Endometrium by the Reticulin-Collagen Phenotype

The histochemical pattern was determined under a light microscope at x100 magnification.

The normal typical pattern of remodeling of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the middle stage of the secretion phase according to the type «reticulin-collagen» (NP) was defined as reticulin fibers that were arranged in an orderly manner, forming clear cellular structures; collagen fibers are thin filamentous ordered, located mainly around blood vessels and glands. The pattern prevails over more than 70% of the histological section.

Abnormal remodeling of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the middle stage of the secretion phase according to the «reticulin-collagen» type has two phenotypes: (1) abnormal noodle-like pattern without collagenosis (aNP); (2) abnormal noodle-like pattern with collagenosis.

Abnormal noodle-like pattern without collagenosis (aNP) was defined as a pattern in which reticulin fibers take on a wavy, tortuous shape, resembling “boiled noodles”. These fibers appear chaotically intertwined, wavy, forming loops, turns and twists with areas of rarefaction and disorganization (

Figure 2g). Importantly, collagen I fibers remain thin, filiform and uniformly distributed in the endometrial stroma around blood vessels and glands, without evidence of focal or diffuse deposits of dense homogeneous collagen masses (

Figure 2h). This reticulin pattern must occupy more than 30% of the histological section to meet the diagnostic criteria for aNP.

Abnormal noodle-like pattern with collagenosis (aNPC) – is characterized by a combination of changes in the reticulin structure (noodle-like pattern) and clusters of collagen fibers. A distinctive feature is the presence of focal or diffuse dense deposits of homogeneous masses of collagen I in the endometrial stroma (

Figure 2l). These changes occupy more than 30% of the area of the histological section and reflect significant changes in the structure of the extracellular matrix.

The patterns are determined under magnification x100 for a general overview and x400 for a detailed assessment of the morphological features of reticulin and collagen fibers.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were subjected to statistical processing using parametric and nonparametric analysis methods. The analysis, systematization and visualization of the obtained results were carried out using the IBMSPSS Statistics v.22 program (StatSoft, Inc., USA). Quantitative variables were initially analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test to determine the normality of distribution using the Levene test to check the homogeneity of variances. For quantitative characteristics, if the distribution was recognized as normal, the mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were calculated. Sets of quantitative indicators, with a different distribution, were described using the median (Me) and the upper and lower quartiles (Q1-Q3). Nominal data are presented as absolute values and percentages. To compare the frequencies of distribution by qualitative characteristics between groups, the chi-square statistical test with Yates’ correction or Fisher’s exact test was used. Proportions are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated by the Clopper-Pearson method. To compare independent populations in cases where there were no signs of normal data distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. When comparing mean values in normally distributed populations of quantitative data, the independent Student’s t-test was calculated. A value was considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Groups

Demographic and clinical baseline characteristics of women from groups with physiological reproductive status and recrudescent reproductive failures are presented in

Table 1.

The groups were comparable in age, BMI, and cycle duration and did not differ in serum levels of TSH, FSH, LH, and E2 measured on the 2nd or 3rd day of the menstrual cycle. At the same time, women with recrudescent reproductive failures had a more significant number of clinical and biochemical pregnancies in the anamnesis and, in 34 (68%) cases, had stimulated cycles.

3.2. Characterization of Histochemical Patterns of Reticulin and Collagen in the Endometrial Extracellular Matrix

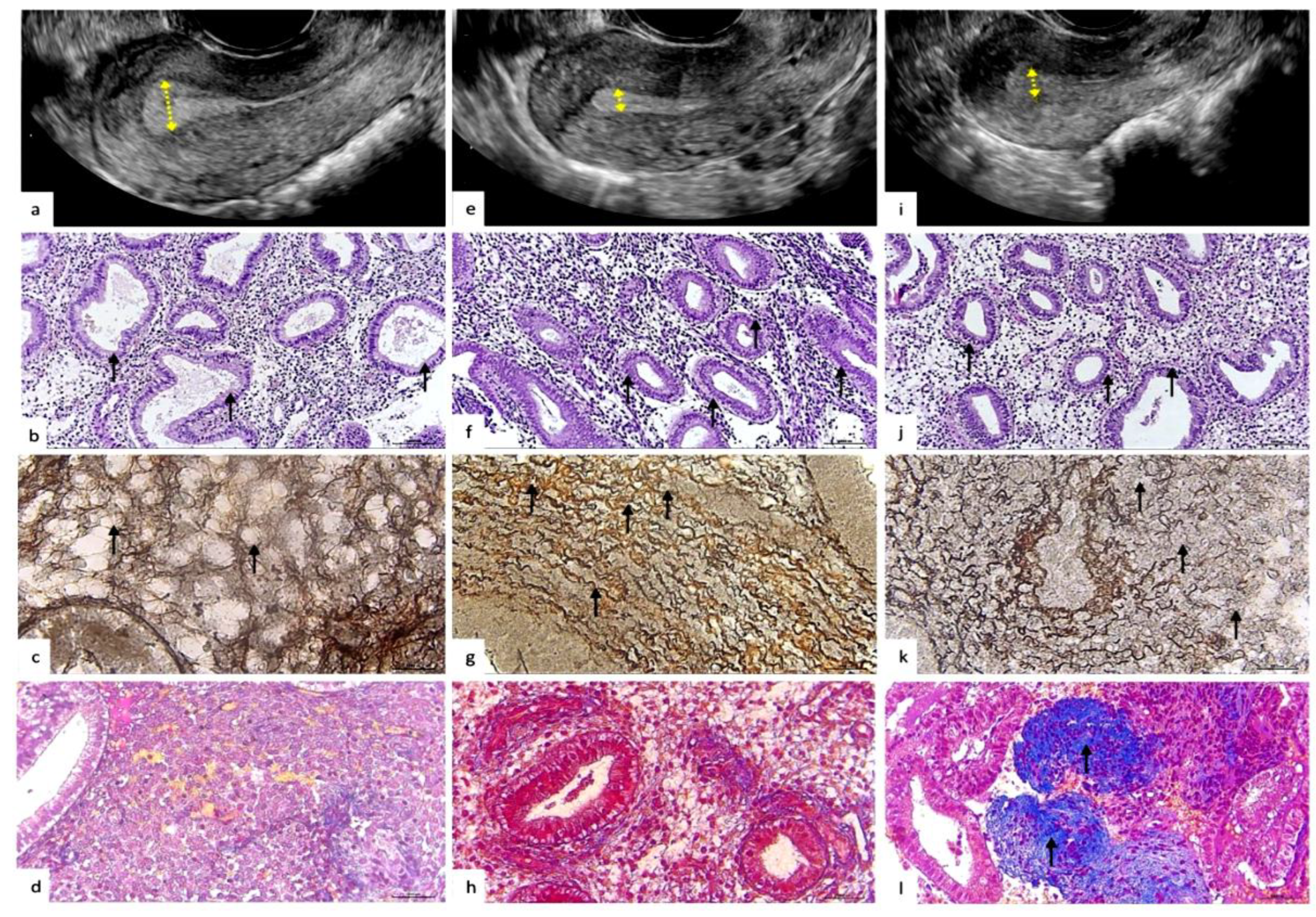

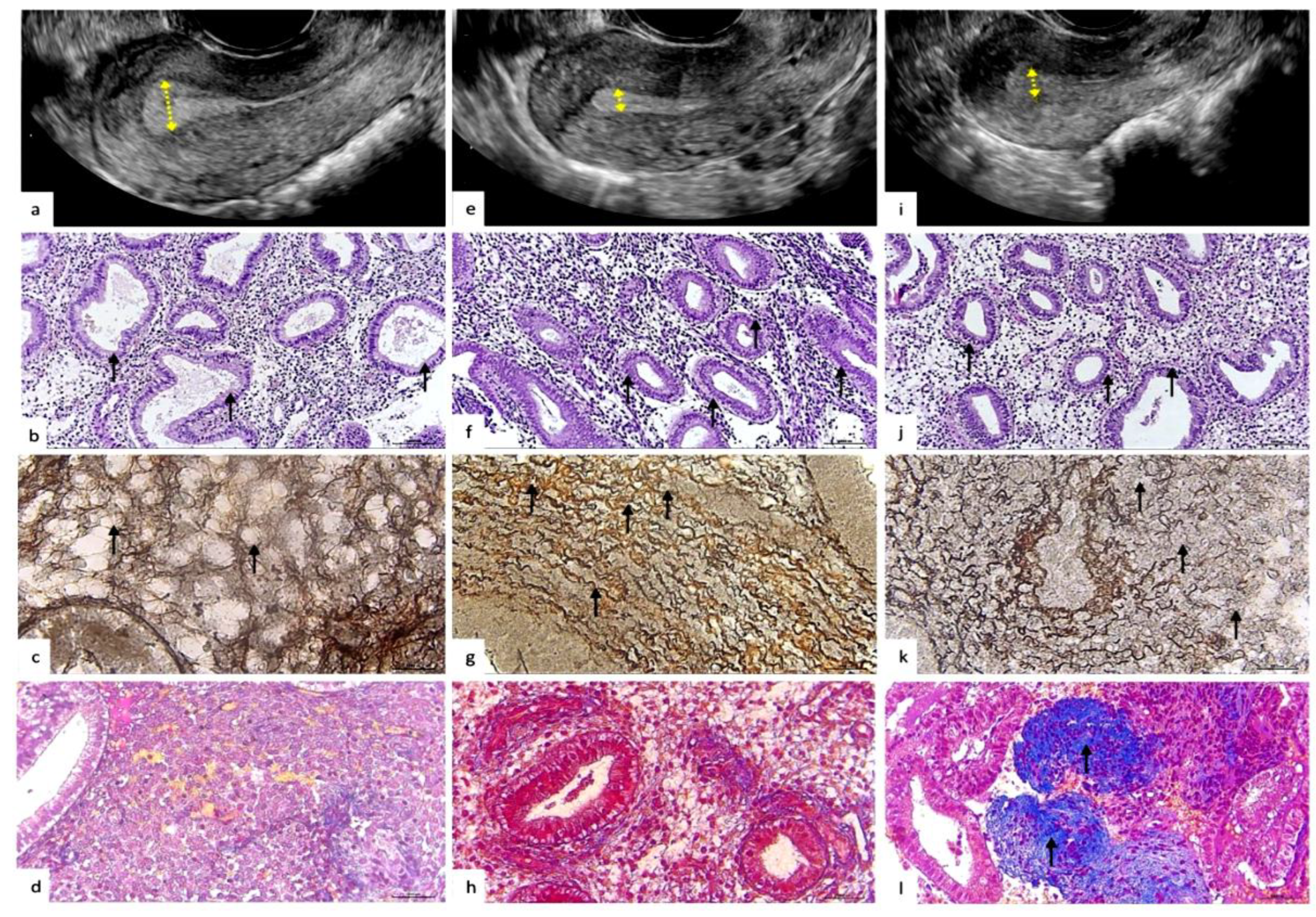

The histochemical pattern of endometrial extracellular matrix remodeling according to the «reticulin-collagen» type is demonstrated in

Table 2 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

In 46(92%) (95% Cl:82.2-97.1%) endometrial biopsies of women with physiological reproductive status, NP was determined in 4(8%) (95% Cl:3.0-17.9%) aNP biopsies; there were no cases with aNPS in this group.

In the group of women with recrudescent reproductive failures, NP was detected in 22(44%) (95% Cl:30.6-58.2%) biopsies, of them with NC 7(28.6%), with SC 15(71.4%). aNP was observed in 21(42%) (95% Cl:28.2-55.9%) biopsies, of them with NC 6(28.6%), with SC 15(71.4%). aNPC in 7 (14%) biopsies, of them with NC 3(42.9%), with SC 4(57.1%).

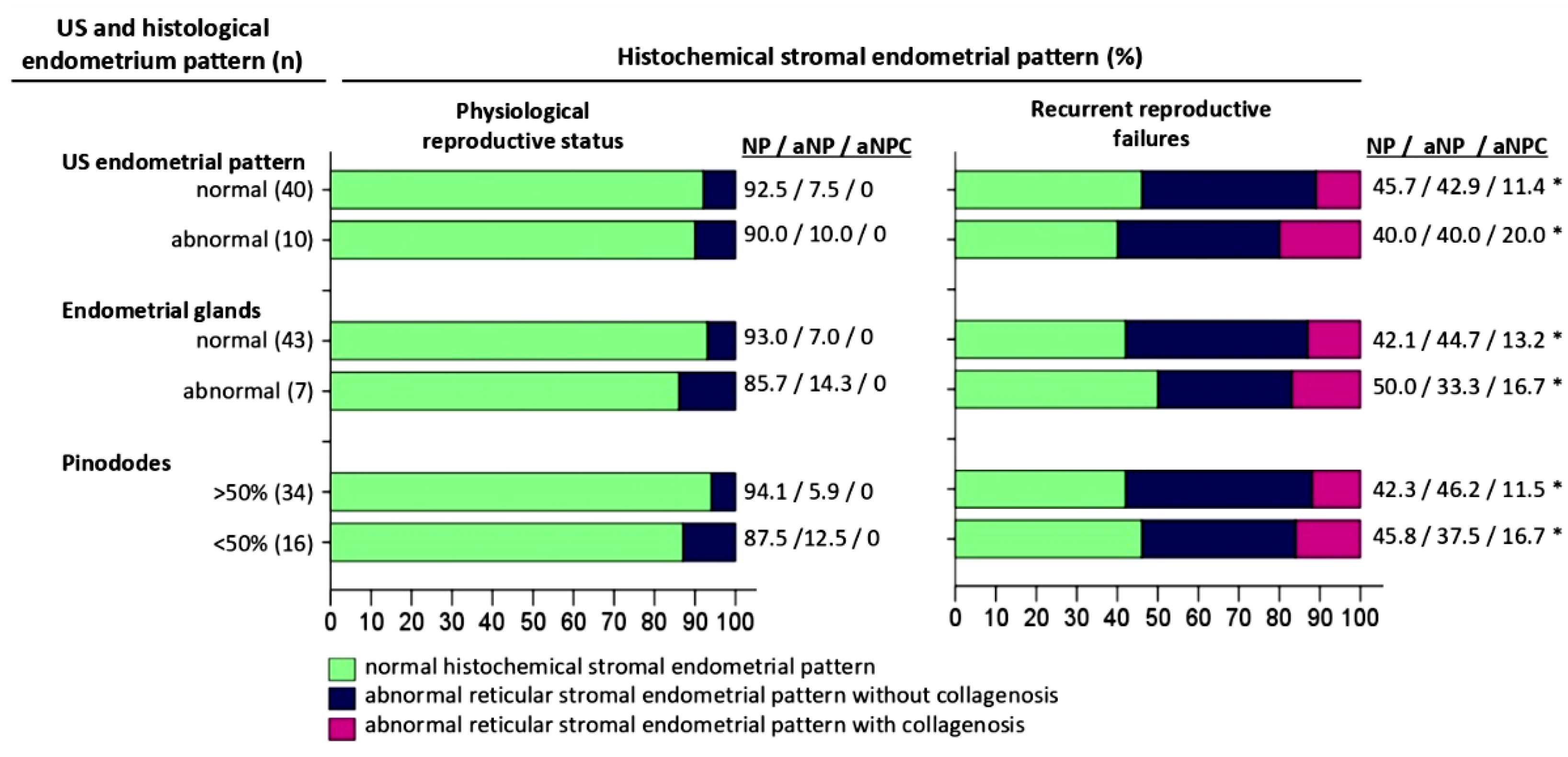

Figure 1.

Comparative characteristics of histochemical pattern, ultrasound and histological pattern of the endometrium from the middle stage secretion phase of menstrual cycle. Abbreviations: US – ultrasonografic investigation, NP - normal histochemical “reticulin-collagen”stromal endometrial pattern, aNP - abnormal reticular stromal endometrial pattern without collagenosis, aNPC - abnormal reticular stromal endometrial pattern with collagenosis (a) Description of what is contained in the first panel; (b) Description of what is contained in the second panel. Figures should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited. Statistically significant difference versus Physiological reproductive status (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparative characteristics of histochemical pattern, ultrasound and histological pattern of the endometrium from the middle stage secretion phase of menstrual cycle. Abbreviations: US – ultrasonografic investigation, NP - normal histochemical “reticulin-collagen”stromal endometrial pattern, aNP - abnormal reticular stromal endometrial pattern without collagenosis, aNPC - abnormal reticular stromal endometrial pattern with collagenosis (a) Description of what is contained in the first panel; (b) Description of what is contained in the second panel. Figures should be placed in the main text near to the first time they are cited. Statistically significant difference versus Physiological reproductive status (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Representative ultrasonographic, histological and histochemical endometrium patterns from physiological and pathological reproductive status. a-d: Ultrasound and histopathological pattern of the endometrium with normal secretory transformation for the middle stage of the secretory phase ovarian cycle. a - Ultrasonography. Homogeneous echogenic endometrium, endometrial thickness – 12 mm (arrows). Echogenic pattern is typical for the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. b - Histopathological pattern. Convoluted endometrial glands with pseudostratified nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm, distinct subnuclear vacuoles located predominantly apically (arrows). The pattern of the glandular epithelium corresponds to the middle stage of the secretion phase. H&E staining: x100. c - Histochemical pattern of stromal reticular fibers (collagen type III). Reticulin fibers are arranged in an orderly manner, forming clear cellular structures; compartmented reticular stromal structure with formation of endometrial stromal channels (arrows). Gomori’s staining: x400. d - Histochemical pattern of stromal collagen (collagen type I). Thin filamentous collagen fibers located in the stroma of the endometrium (arrows). Masson’s trichrome staining: x100. e-l: Ultrasound and histopathological pattern of the endometrium with defective/insufficient and irregular secretory transformation of the glandular and stromal compartments. e,i - Ultrasonography. Thin endometrium, thickness 5.5mm and 6.5mm, respectively (arrows). f,j - Histopathological pattern. Endometrial glands with pseudostratified nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm and distinct parabasal vacuoles (arrows). The pattern of glandular epithelium with delayed secretory transformation, corresponds to the early stage of the secretion phase. H&E staining: x100. g,k - Histochemical pattern of stromal reticular fibers (collagen type III). g - Reticulin fibers are disordered, wave-like, tortuous, “noodle-like” pattern (arrows). k - Reticulin fibers with diffuse edema with microfragmentation and areas of disorganization (arrows). Gomori’s staining: x400. h,l - Histochemical pattern of stromal collagen (collagen type I). h – Normal fine thread-like ordered collagen fibers, located mainly around the vessels and glands. l – Abnormal foci of periglanduar and perivascular deposition of homogeneous collageneous masses (arrows). Masson’s trichrome staining: x100.

Figure 2.

Representative ultrasonographic, histological and histochemical endometrium patterns from physiological and pathological reproductive status. a-d: Ultrasound and histopathological pattern of the endometrium with normal secretory transformation for the middle stage of the secretory phase ovarian cycle. a - Ultrasonography. Homogeneous echogenic endometrium, endometrial thickness – 12 mm (arrows). Echogenic pattern is typical for the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. b - Histopathological pattern. Convoluted endometrial glands with pseudostratified nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm, distinct subnuclear vacuoles located predominantly apically (arrows). The pattern of the glandular epithelium corresponds to the middle stage of the secretion phase. H&E staining: x100. c - Histochemical pattern of stromal reticular fibers (collagen type III). Reticulin fibers are arranged in an orderly manner, forming clear cellular structures; compartmented reticular stromal structure with formation of endometrial stromal channels (arrows). Gomori’s staining: x400. d - Histochemical pattern of stromal collagen (collagen type I). Thin filamentous collagen fibers located in the stroma of the endometrium (arrows). Masson’s trichrome staining: x100. e-l: Ultrasound and histopathological pattern of the endometrium with defective/insufficient and irregular secretory transformation of the glandular and stromal compartments. e,i - Ultrasonography. Thin endometrium, thickness 5.5mm and 6.5mm, respectively (arrows). f,j - Histopathological pattern. Endometrial glands with pseudostratified nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm and distinct parabasal vacuoles (arrows). The pattern of glandular epithelium with delayed secretory transformation, corresponds to the early stage of the secretion phase. H&E staining: x100. g,k - Histochemical pattern of stromal reticular fibers (collagen type III). g - Reticulin fibers are disordered, wave-like, tortuous, “noodle-like” pattern (arrows). k - Reticulin fibers with diffuse edema with microfragmentation and areas of disorganization (arrows). Gomori’s staining: x400. h,l - Histochemical pattern of stromal collagen (collagen type I). h – Normal fine thread-like ordered collagen fibers, located mainly around the vessels and glands. l – Abnormal foci of periglanduar and perivascular deposition of homogeneous collageneous masses (arrows). Masson’s trichrome staining: x100.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Histochemical Patterns of the Endometrial Extracellular Matrix and Ultrasonography Endometrial Pattern

The ultrasonography pattern of the endometrium is presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 2.

In the group with physiological reproductive status in 40(80%) (95% Cl:73.7-88.9%) women, a homogeneous endometrium with central echogenic line and thickness of more than 7 mm was determined by ultrasonography examination (

Figure 2,а), of them with NP 37(92.5%) and aNP 3(7.5%) endometrial biopsies. On the other hand, the ultrasonography pattern did not correspond to the stage of secretion in 10(20%) (95% Cl:10.7-32.4%) biopsies, of them with NP 9(90%) and with aNP 1(10%) cases.

In the group of women with recrudescent reproductive failures, an ultrasonography pattern corresponding to the middle stage of the secretion phase was observed in 35(70%) (95% Cl:58.9-78.3%) cases, of them with NP 16(45.7%), with aNP 15(42.9%), with aNPC 4(11.4%) biopsies; with NC 10(28.6%), with SC 25(71.4%). On the other hand, ultrasonography pattern not corresponding to the middle stage of the secretion phase was detected in 15(30%) (95% Cl:19.7-43.9%) biopsies, of them with NP 6(40%), aNP 6(40%), aNPC 3(20%); with NC 6(40%) and SC 9(60%).

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Histochemical Patterns of Extracellular Matrix and Histological Features of Glandular Epithelium of the Endometrium

The histophenotype of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the middle stage of the secretion phase and the histological pattern of the glandular endometrium are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 2,b,f,j.

In the group of women with physiological reproductive status 43(86%) (95% Cl:78.9-92.9%) biopsies showed convoluted endometrial glands with pseudo laminated nuclei and vacuolized cytoplasm, clear subnuclear vacuoles located mainly apically with the presence of secretions in the lumen of the glands (Figure 4), of them with NP 40(93%) and aNP 3(7%) endometrial biopsies. The histological pattern of the glandular epithelium did not correspond to the middle phase of the secretion stage in 7(14%) (95% Cl:6.2-26.1%) biopsies, of them with NP 6(85.7%) and aNP 1(14.3%).

In the group of women with recrudescent reproductive failures, in 38(76%) (95% Cl:64.4-84.2%) cases, the histophenotype of the endometrial glands corresponded to the middle stage of the secretion phase (Figure 5), of them with NP 16(42.1%), with aNP 17(44.7%), with aNPC 5(13.2%) biopsies, with NC 11(28.9%) and SC 27(71.1%). Although, the histological pattern of the glands did not correspond to the intermediate stage of the secretion phase in 12(24%) (95% Cl:13.9-37.4%) biopsies, of them with NP 6(50%), with aNP 4(33.3%), with aNPC 2(16.7%); with NC 5(41.7%) and SC 7(58.3%).

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Histochemical Patterns of Extracellular Matrix and the Number of Pinopodia in the Endometrial Epithelium in the Middle of the Secretory Phase

The relative number of the pinopods

of the superficial endometrial epithelium are presented in

Table 5.

In the group of women with physiological reproductive status pinopods covering most (>50%) of the apical cell membrane were observed in 34(68%) (95% Cl:57.6-77.6%) biopsies, of them with NP 32(94.1%) and aNP 2(5.9%). Pinopods covering a minor part (<50%) of the apical cell membrane were detected in 16(32%) (95% Cl:20.9-43.8%) biopsies, of them with NP 14(87.5%) and aNP 2(12.5%) cases.

In the group of women with recrudescent reproductive failures, pinopods covering >50% of the apical cell membrane were observed in 26(52%) (95% Cl:40.0-63.5%) biopsies, of them with NP 11 (42.3%), aNP 12(46.2%) and aNPC 3(11.5%); with NC 9(34.6%) and SC 17(65.4%) biopsies. On the other hand, pinopods covering less than 50% of the apical membrane were detected in 24(48%) (95% Cl:36.5-60.0%) biopsies, of them with NP 11(45.8%), aNP 9(37.5%), with aNPC 4(16.7%); NC 7(29.2%) and SC 17(70.8%) cases.

4. Discussion

We compared the histochemical pattern of the middle secretory endometrium with the ultrasonography pattern, the histological pattern of glandular epithelium, and relative number of the pinopods between groups of women with recrudescent reproductive failures and physiological reproductive status.

We found that the histochemical pattern of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the «reticulin-collagen» type differs in physiological reproductive status and in recrudescent reproductive failures (p<0.05). Thus, we identified two histochemical patterns: the first with ordered reticulin fibers forming clear cellular structures (

Figure 2c), associated in more than 90% of cases with physiological reproductive status.

The second type of extracellular matrix is characterized by disordered reticulin fibers that acquire a wavy, tortuous shape, forming loops, turns and twists resembling “boiled noodles” (

Figure 2,g) with diffuse rarefactions and areas of disorganization (

Figure 2k), which was observed in more than 50% of cases of recurrent reproductive disorders.

In turn, this stromal pattern, that often associated with reproductive failures, has two main phenotypes: (1) abnormal noodle-like pattern without collagenosis (aNP) (

Figure 2h); (2) abnormal noodle-like pattern with collagenosis (aNPC) (

Figure 2l). We believe that the abnormal histochemical phenotype of reticulin-collagen of the endometrial stroma may reflect the pathological remodeling of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the middle stage of the secretion phase.

Further, we found that the abnormal reticulin-collagen pattern of the endometrial stroma was detected in all groups: with physiological reproductive status in less than 10 percent of cases and with recrudescent reproductive failures in more than 50% of cases, despite the fact that pathological remodeling of the extracellular matrix with collagenosis, characterized by focal and diffuse well-visually detecs collagen bundles, was noted only with recrudescent reproductive failures, but with physiological pregnancy no cases of collagenosis were found. Qualitative and quantitative disorders and collagen abnormalities in the stroma were previously described in the intestine with collagenous microscopic colitis [

58,

59,

60] and decidual tissue with clinically unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss [

20,

61]. It is unclear whether abnormal collagen expression is the cause or result of recrudescent miscarriage, but as previously shown [

62,

63,

64,

65], collagen may play an important role in indicating immune tolerance. Furthermore, the adequate remodeling of the collagenous extracellular matrix of the endometrium of the middle phase of the cycle plays an important role in forming a favorable implantation field and the diffusion and perfusion potential of the endometrium for implanted blastocytes. Our findings are consistent with and complement previous studies [

30,

66] by showing that focal collagen remodeling plays an important role in recurrent reproductive failure. This observation highlights the need for further studies to refine our understanding of the dynamics of interactions between structural components of the endometrial extracellular matrix in the context of reproductive failure.

Further, we showed that in the group with physiological reproductive status, in more than 90% of biopsies, clearly formed mesh-cellular structures of the «honeycomb» type with evenly distributed thin reticulin fibers and single filamentous collagen fibers were determined. Similar structures were described earlier in chorionic villi, represented as stromal channels, the value of which is defined as the formation of connecting links implementing the function of transport and exchange between mother and fetus [

67]. We believe that normal remodeling of proteins, in particular reticulin-collagen, the extracellular matrix of the endometrium with physiological reproductive status is necessary for the formation of stromal channels to increase and improve the diffusion potential of the endometrium during implantation of blastocysts. Previously was shown that pronounced edema develops in the endometrial stroma during implantation [

68]. In our study, in more than 50% of cases with recrudescent reproductive failures, we found histopathological signs of diffuse edema of the endometrial stroma with fibrinization and disorganization of reticulin and collagen fibers. In contrast, in the group with physiological reproductive status, such a histopattern was absent and characterized only by the stroma’s micro-focal rarefaction. We believe that the normal remodeling of the endometrial matrix is associated not so much with stroma edema as with the formation of a highly specialized stromal skeleton with the presence of stromal channels, and stromal edema highly likely is a pathological structural change in the endometrium, which can mimic the normal ultrasound and histological pattern.

We found that endometrial ultrasonography patterns and histophenotype differed between the groups. In the group with recrudescent reproductive failures, cases were often associated with a thin endometrium (

Figure 2e,i,f,j), delayed maturation of the glandular epithelium, and a low number of pinopods in comparison with the endometrium from physiological reproductive status.

The cases with stimulated menstrual cycle and reproductive failures were more often associated with ultrasonographic and histological signs of mature and complete endometrium, in comparison with the subgroup with natural menstrual cycle and reproductive failures. This finding confirms previously published data that hormonal stimulation of the cycle accelerates the endometrium’s maturation and increases the endometrium’s thickness [

69,

70]. However, statistically significant differences were not found between the hormonal induced and non-induced cycle (p>0.05) when assessing the histochemical phenotype «reticulin-collagen». This may indicate the existence of endogenous factors that play a key role in the pathological regulation of the endometrial extracellular matrix, not directly related to hormonal stimulation, which are manifested in both induced and natural cycles and require further study.

Our study showed significant differences in the histopatterns of the endometrial extracellular matrix in physiological reproductive status and in recurrent reproductive failures. However, it remains unclear whether these changes are the cause of reproductive disorders or their consequence.

Persistent inflammation and hormonal imbalance can initiate structural disorders of the extracellular matrix, creating unfavorable conditions for blastocyst implantation. In particular, proinflammatory cytokines mediate hyperactivity of matrix metalloproteinases, which leads to degradation of key components of the extracellular matrix and disorganization of its structure [

71,

72,

73]. Genetic factors, particularly mutations in genes encoding matrix components such as collagen or matrix metalloproteinases, may also reduce the ability of the endometrium to support blastocyst implantation and trophoblast invasion. On the other hand, implantation failures may trigger compensatory remodeling characterized by excessive collagen accumulation and dysfunctional matrix regulation. This may form a “vicious circle” where abnormalities in the structure of the endometrial extracellular matrix enhance subsequent reproductive failures. Longitudinal studies aimed at studying the dynamics of the histophenotype of the endometrial extracellular matrix at different periods of the menstrual cycle, as well as at different stages of pregnancy planning, are needed to elucidate this relationship in more detail.

We also identified 2 (4%) cases with thin and immature histological and abnormal histochemical endometrial pattern in the group with physiological reproductive status, which were associated with unfavorable pregnancy outcome with placental abruption and intrauterine fetal growth retardation. Previously, several papers showed that the pathological thin and immature endometrium for the phase of menstrual cycle is often associated with antenatal hypoxic-ischemic events in the placenta and fetus [

74,

75]. Therefore, we believe that pathological remodeling of the extracellular matrix of the endometrium is a high risk factor not only for reproductive failures but also for long-term adverse consequences of pregnancy. However, this statement is speculative and requires further study.

It can be assumed, on the one hand, the discrepancy between endometrial ultrasonography and histopattern may be associated with delay in the growth and maturation of the endometrium; on the other hand, it may be due to the persistence of insufficient endometrial remodeling, which cases may indirectly be indicated with collagenosis of the extracellular matrix in the group with recrudescent reproductive losses, which in our study were not detected with physiological reproductive status.We propose the use of the term «insufficient secretory endometrial transformation», which refers to the structural inconsistency of the glandular or extracellular matrix of the endometrium for the phase of the menstrual cycle according to a combination of ultrasonography, histological and histochemical examination methods of the endometrium and which allows to stratify a group of women with high risk of insufficient/abnormal formation of endometrial implantation platform with structural inconsistence of the epithelial-stromal compartment of the endometrium.

The strengths of this study include comparative characteristics of the histophenotypic pattern of the endometrium of the middle secretory phase in recrudescent reproductive failures and in physiological reproductive status. Limitations of the study include data fluctuations that may be due to the small number of cases in subgroups, as well as the lack of long-term follow-up to assess the impact of the identified histophenotypes on conception and pregnancy outcomes. Conducting multicenter studies with an increased sample size and taking into account different cycle stimulation protocols will increase the representativeness and validity of the results. To clarify the prognostic role of histochemical patterns of the endometrial extracellular matrix, it is necessary to conduct long-term longitudinal studies that will assess the impact of histophenotype on conception, implantation success and pregnancy outcomes. These studies will contribute to the development of a personalized approach in reproductive medicine, clarify the prognostic significance of the identified histophenotypes and can facilitate integration into clinical practice to improve risk stratification and prognosis of reproductive losses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.O., D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; methodology, N.O., D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; validation, D.K., Ye. K., and I.K.; formal analysis, N.O., R.G., Ye. K., K.M., and I.K.; investigation, N.O., R.G., K.M., Ye. K., and I.K.; resources, D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; data curation, D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.O.; writing—review and editing, D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; supervision, D.K., A.T., and Zh.A.; project administration, N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.