Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

- Integration of Graph Laplacian Embedding with RPCA We incorporate graph Laplacian embedding into RPCA to account for the spatial information inherent in the data. By representing the data as a graph, where nodes correspond to data points and edges reflect pairwise relationships (such as similarity or distance), the graph Laplacian matrix effectively captures the dataset’s underlying geometric structure.

- Exploitation of Two-Sided Data Structure We leverage a dual perspective by obtaining the graph Laplacian from both the sample and feature dimensions. This approach enables us to capture intrinsic relationships not only among data points (samples) but also among features, thereby providing a more holistic representation of the data.

- Introduction of Anchors for Computational Efficiency We introduce the concept of anchors to enhance the model’s running speed and reduce computational complexity. Anchors serve as representative points that summarize the data’s structure, thereby minimizing the number of pairwise comparisons needed during graph construction. Instead of computing relationships between all data points, we select a subset of anchors (using methods like random sampling, K-means, or other clustering techniques) and construct the graph based on the relationships between data points and these anchors. This method significantly reduces the size of the adjacency matrix and, consequently, the computational burden associated with the graph Laplacian.

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| X | data matrix of size |

| n | number of samples |

| m | number of features |

| the i-th column of X | |

| the i-th row of X | |

| the trace norm of the matrix A | |

| the Frobenius norm of the matrix A |

1. Preliminaries

1.1. Quaternion and Quaternion Matrix

- .

- , where denotes transpose operation.

- A is a column unitary matrix if and only if is a column orthogonal matrix.

1.2. Graph

- For each vector , we have

- L is symmetric and positive semi-definite.

- The smallest eigenvalue of L is 0, and corresponding eigenvector is 1 whose elements are all ones.

- L has n non-negative real eigenvalues .

1.3. Graph Laplacian Embedding

1.4. Anchors

-

K-means method for anchor pointsWe adopt the K-means clustering algorithm to derive a set of anchor points, which serve as representative prototypes for the underlying data distribution. Considering a dataset , the K-means algorithm aims to partition X into k disjoint clusters by minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares, formulated as [31]where denotes the i-th cluster and is its centroid, namely the anchor points.

-

BKHK method for anchor pointsThe Balanced and Hierarchical K-means (BKHK) algorithm is a hierarchical anchor point selection method that combines K-means and hierarchical clustering to recursively construct evenly distributed anchor points, thereby improving representation ability. In contrast to conventional K-means algorithms that execute a single-step partitioning of the dataset into a predetermined number of clusters, BKHK employs a hierarchical partitioning strategy. It recursively divides the dataset X into m sub-clusters, performing binary K-means at each step. This process continues until the desired number of clusters is achieved. The objective function of Balanced Binary K-means is defined as follows [32]where represents the two class centers, and is the class indicator matrix.

2. Methodology

3. Experiments

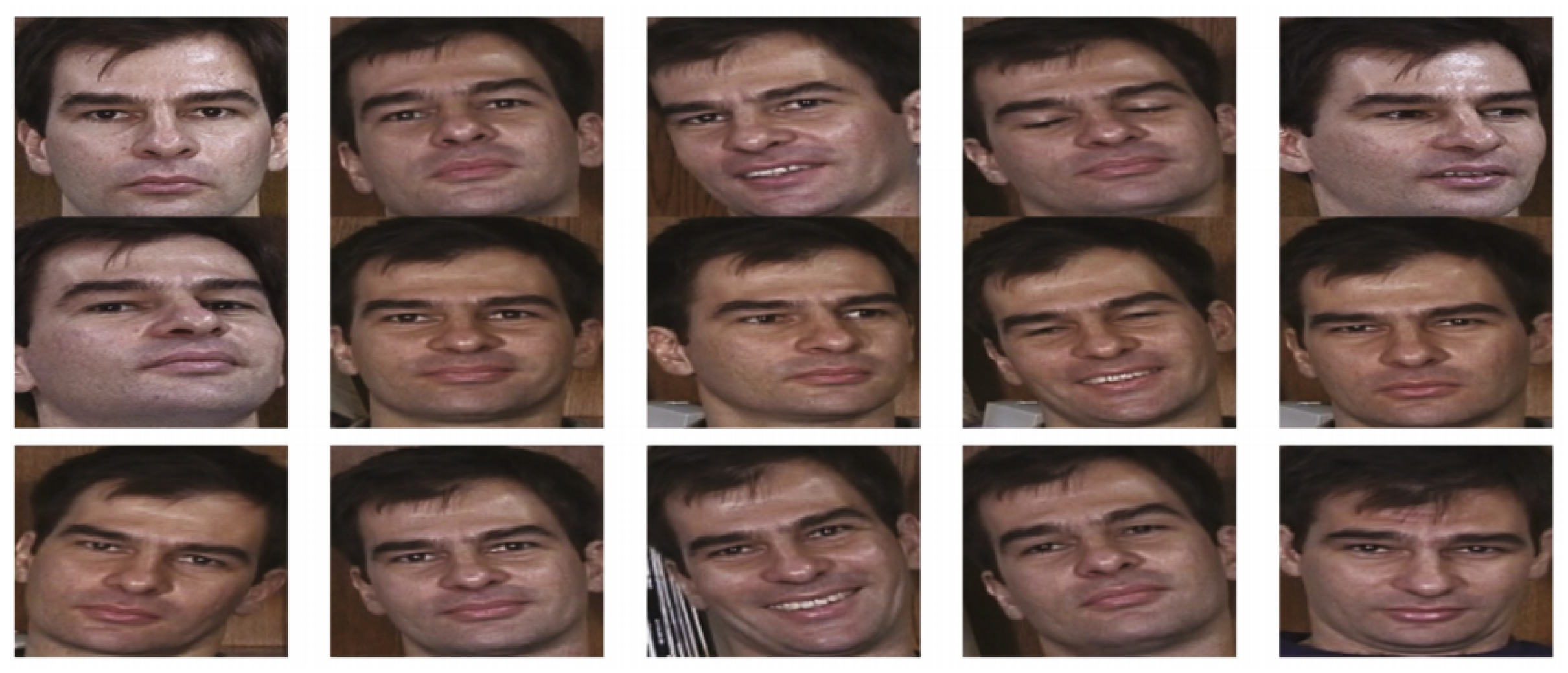

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Parameter Selection

3.3. Experiment Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirby, M.; Sirovich, L. Application of the Karhunen-Loeve procedure for the characterization of human faces. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1990, 12, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Pentland, A. Eigenfaces for recognition. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 1991, 3, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, D.; Frangi, A.F.; Yang, J.Y. Two-dimensional PCA: A new approach to appearance-based face representation and recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 26, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, L.; Reutter, J.Y.; Lorente, L. The importance of the color information in face recognition. IEEE International Conference on Image Processing 1999, 3, 627–631. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Liu, C. A general discriminant model for color face recognition. IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer Vision 2007, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q. Color face recognition by PCA-like approach. Neurocomputing 2015, 228, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Li, X. Improved principal component analysis and linear regression classification for face recognition. Signal Process. 2018, 145, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Ganesh, A.; Rao, S.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y. Robust Principal Component Analysis: Exact Recovery of Corrupted Low-rank Matrices via Convex Optimization. Proc, Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2009, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Candès, E.J.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wright, J. Robust principal component analysis. J. ACM 2009, 58, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Ma, Y. Dense error correction via l1-minimization. lEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 3540–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Tao, D. Greedy Bilateral Sketch, Completion & Smoothing. Proc. IMLR Workshop Conf 2013, 31, 650–658. [Google Scholar]

- Bihan, N. Le; Sangwine, S.J. Quaternion principal component analysis of color images. Proc. Int. Conf. Image Process. 2003, 809–812. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z. The Eigenvalue Problem of Quaternion Matrix: Structure-Preserving Algorithms and Applications. Beijing, China: Science Press 2019.

- Denis, P.; Carre, P.; Fernandez-Maloigne, C. Spatial and spectral quaternionic approaches for colour images. Comput. Vis. Image Understand. 2007, 107, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi,L. ; Funt, B. Quaternion color texture segmentation. Comput. Vis. Image Understand. 2007, 107, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou,C. ; Kou, K.I.; Wang, Y. Quaternion collaborative and sparse representation with application to color face recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 3287–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chen,Y. ; Gong, Y.J.; Zhou, Y. 2D quaternion sparse discriminant analysis. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 2271–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen,Y. ; Xiao,X.; Zhou,Y. Low-rank quaternion approximation for color image processing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.W.; Xie, L.M.; Gao, Z.H. A Survey on Solving the Matrix Equation AXB = C with Applications. Mathematics 2025, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.R.; Wang, Q.W. The General Solution to a System of Tensor Equations over the Split Quaternion Algebra with Applications. Mathematics 2025, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; He, X.F.; Han, J.W.; Huang, T.S. Graph regularized nonnegative matrix factorization for data representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Ding, C.; Luo, B.; Tang, J. Graph-laplacian PCA: closed-form solution and robustness. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Gao, Y.L.; Liu, J.X.; Zheng, C.H.; Yu, J. PCA based on graph laplacian regularization and P-norm for gene selection and clustering. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 2017, 16, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y.L.; Zheng, C.H.; Shang, J.L.; Liu, F.; et al. A joint-L2,1-norm-constraint-based semi-supervised feature extraction for RNA Seq data analysis. Neurocomputing 2017, 228, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.X.; Kong, X.Z.; Yuan, S.S.; Dai, L.Y. Laplacian regularized low-rank representation for cancer samples clustering. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 78, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.Y.; Duan, X.F.; Li, C.M.; Wang, Q.W. A new algorithm for solving a class of matrix optimization problem arising in unsupervised feature selection. Numer. Algor. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.R. Lectures on Quaternions. In Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940; Hodges and Smith: Dublin, Ireland 1853. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. Algebraic methods for diagonalization of a quaternion matrix in quaternionic quantum theory. J. Math. Phys. 2005, 46, 052106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, C.; Jin, D.; Ding, S.F. Survey of spectral clustering based on graph theory. Pattern Recognition 2024, 151, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.X.; Zheng, C.H.; Yuan, S.S.; Wang, J.; Dai, L.Y. Joint Lp-Norm and L2,1-Norm Constrained Graph Laplacian PCA for Robust Tumor Sample Clustering and Gene Network Module Discovery. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 621317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.l. Design and Implementation of an Improved K-Means Clustering Algorithm. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 6041484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; Chen, W.Z.; Nie, F.P.; Yu, W.Z.; Wang, Z.H. Spectral clustering with linear embedding: A discrete clustering method for large-scale data. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 151, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Georgia Tech face database. http://www.anefian.com/research/face_reco.htm.

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Running Time (s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard graph Laplacian | 73.8% | 991.94 | Baseline method |

| K-means + graph Laplacian | 73.3% | 935.39 | K-means for anchor selection |

| BKHK + graph Laplacian | 73.3% | 973.15 | BKHK for anchor selection |

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Running Time (s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard graph Laplacian | 73.3% | 2924.71 | Baseline method |

| K-means + graph Laplacian | 72.9% | 2765.83 | K-means for anchor selection |

| BKHK + graph Laplacian | 72.9% | 2132.40 | BKHK for anchor selection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).