1. Introduction

Group A

Streptococcus (GAS) is a gram-positive, non-motile bacterium and a common cause of acute pharyngitis, which affects approximately 5%–15% of adults and 20%–30% of children [

1]. In Japan, GAS pharyngitis (GAS-P) typically exhibits seasonal outbreaks, which occur from winter to spring and during summer. Typical manifestations of GAS-P include a sudden onset of fever, sore throat, and recent contact with infected individuals. In some cases, it can lead to severe complications such as pneumonia or bacteremia [

1,

2]. Additionally, GAS infections can trigger immune-mediated complications, including post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever, which can result in renal impairment and systemic effects [

1]. The first-line antimicrobial treatment for GAS-P and the prevention of complications is a penicillin-based antibiotic, with macrolides acting as alternative options [

1].

Following the onset of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic in 2020, the incidence of upper respiratory infections, including GAS-P, significantly declined worldwide owing to lockdowns (declared as a state of emergency in Japan) and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) [

3,

4,

5]. In Japan, a sharp decline was observed after May 2020; however, GAS-P cases began resurging in May 2023 [

2,

6]. Similarly, in Europe, a resurgence of GAS infections was reported from September 2022 onward, and by 2023, the incidence had returned to or surpassed pre-pandemic levels [

7,

8].

Despite these trends, the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and GAS remains unclear. To date, only two cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and GAS-P co-occurrences have been reported, both during the early Delta variant period. No updated reports on co-infections have been published since the emergence of the Omicron variant [

9,

10]. The pathophysiology of co-infection and potential microbial interactions between GAS and SARS-CoV-2 remains unclear, partly because of the limited number of reported cases.

In this study, we examined the trends in GAS-P incidence, including those among adult patients, in a single institution and explored pathophysiological considerations for co-infection cases.

2. Materials and Methods

This single-center retrospective observational study was conducted between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2024, among patients who visited Tokyo Shinagawa Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. We retrospectively collected data from patient’s medical records, including age, sex, and GAS and SARS-CoV-2 test results for those who underwent GAS testing. GAS testing was primarily performed by internal medicine physicians, otolaryngologists, and pediatricians in the fever and emergency outpatient departments for patients clinically suspected of having pharyngitis. GAS infection was diagnosed when the

Streptococcus A antigen was detected using Capilia Strep A (©TAUNS), which has a sensitivity of 93.1% and a specificity of 100% [

11]. Oropharyngeal swabs were collected from specialized nurses.

We defined two points marking changes in GAS transmission dynamics: May 2020 (following the first state of emergency declaration in Japan) and May 2023 (after the relaxation of mask mandates, the conclusion of the WHO Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the reclassification of COVID-19 from Category II to Category V in Japan), based on findings from previous Japanese studies [

2,

6].

To analyze these changes, we divided the study period into three distinct phases: pre-COVID social period (January 2019–April 2020), restricted social period (May 2020–April 2023), and post-restriction period (May 2023–December 2024). We compared patient backgrounds, including demographics and clinical characteristics, across these three periods to evaluate the impact of pandemic-related interventions on GAS transmission and incidence trends.

For statistical analysis, we used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare age distributions among the three periods, while Fisher’s exact test was applied to compare GAS positivity rates, sex distribution, and the proportion of pediatric cases. Pairwise comparisons between two periods were subsequently performed using t-tests for age and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.3 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The number of GAS tests performed and positive results in our hospital were compared with the reported incidence of GAS-P in the Tokyo Notifiable Disease Surveillance [

6]. For further investigation, the background, symptoms, and clinical course of patients who tested positive for both GAS antigen and SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) simultaneously were extracted, and these data were presented in

Table 1. The microbiological diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 was performed using different testing methods over the study period as follows:

May 7, 2020–November 8, 2022: In-house PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2

May 27, 2020–December 31, 2020: Antigen testing using QuickNavi-COVID19 Ag (Denka Co., Ltd., Japan)

December 28, 2020–February 20, 2023: ID NOW COVID-19 test (Abbott, US)

November 9, 2022–Present: GeneXpert SARS-CoV-2 test (Cepheid Netherlands B.V., Netherlands)

The criteria for positive results followed contemporary COVID-19 treatment guidelines [

12].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Shinagawa Hospital (no. 22-A-14). Consent was obtained using the “opt-out method,” thereby allowing patients to decline participation. Therefore, the research ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent.

3. Results

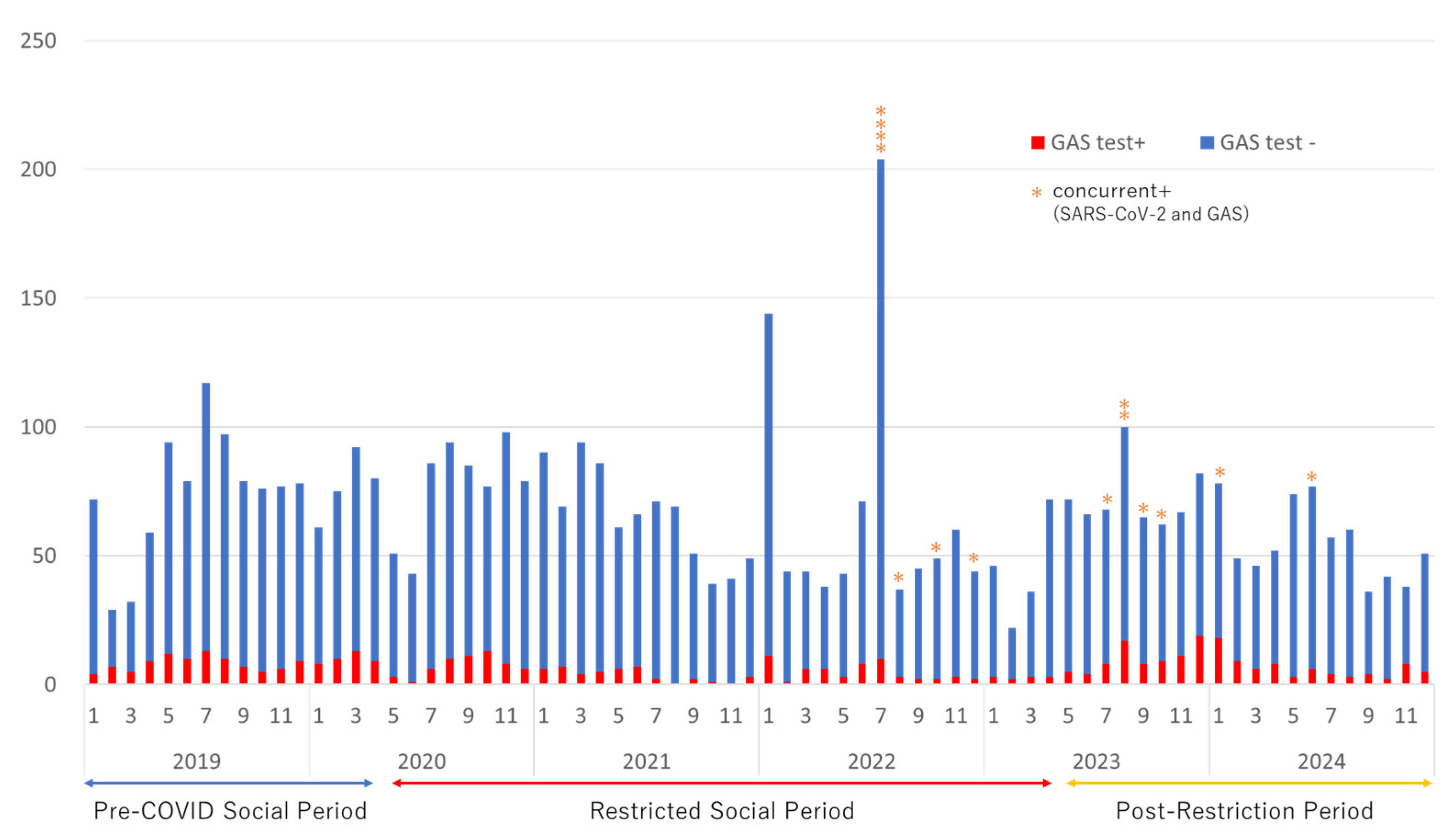

During the study period, a total of 4,837 GAS tests were performed, of which 463 (9.6%) yielded positive results. The number of tests conducted ranged from 22 to 117 per month, except in January and July 2022. The monthly trends in GAS test results are summarized in

Figure 1, while the age and sex distribution of positive cases are presented in

Table 2. Among all GAS-positive patients, 278 (60.0%) were male, and the overall mean age ± standard deviation (SD) was 28.0 ± 17.2 years (

Table 1). Overall, 346 (74.7%) positive cases were aged ≥15 years, whereas 117 (25.3%) were children aged <15 years.

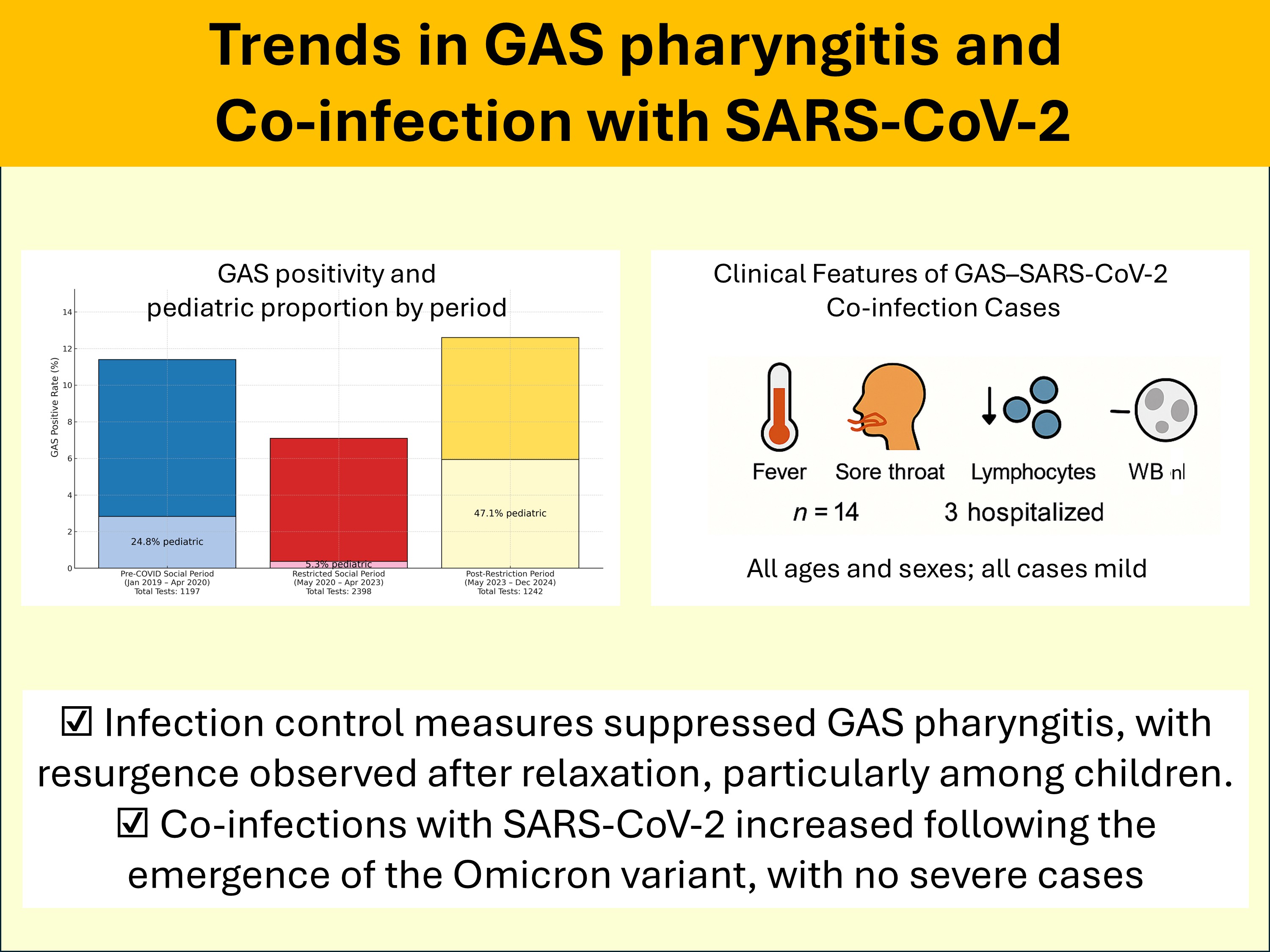

To assess temporal trends, we categorized the study period into three distinct phases: the pre-COVID social period (January 2019–April 2020), the restricted social period (May 2020–April 2023), and the post-restriction period (May 2023–December 2024). The positivity rate was 11.4% (137/1,197) in the pre-COVID social period, significantly decreasing to 7.1% (169/2,398, p = 0.000015 vs. pre-COVID) during the restricted social period, and then increasing to 12.6% (157/1,242, p < 0.001 vs. restricted, p = 0.459 vs. pre-COVID) in the post-restriction period. The proportion of male patients remained relatively stable across the three periods: 59.1% (81/137) in pre-COVID, 63.3% (107/169) in restricted (p = 0.48 vs. pre-COVID), and 57.3% (90/157) in post-restriction (p = 0.31 vs. restricted). The mean age of GAS-positive patients was 27.8 ± 16.5 years in the pre-COVID period, significantly increasing to 33.1 ± 14.3 years (p = 0.0029 vs. pre-COVID) in the restricted period, followed by a significant decline to 22.6 ± 18.9 years (p < 0.001 vs. restricted, p = 0.013 vs. pre-COVID) in the post-restriction period. The proportion of children aged <15 years was 24.8% (34/137) in pre-COVID, which significantly decreased to 5.3% (9/169, p < 0.001 vs. pre-COVID) during the restricted period, then markedly increased to 47.1% (74/157, p < 0.001 vs. restricted, p = 0.00010 vs. pre-COVID) in the post-restriction period.

These findings indicate a significant reduction in GAS positivity rates and pediatric cases during the restricted social period, followed by a sharp resurgence in the post-restriction period, particularly among younger age groups.

Among the patients who tested positive for GAS, 151 underwent simultaneous SARS-CoV-2 testing throughout the study period (2019: 0 cases; 2020: 21 cases; 2021: 5 cases; 2022: 42 cases; 2023: 43 cases; 2024: 40 cases), and 14 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The positive cases are marked with an asterisk (*) in

Figure 1 and

Table 2, while their clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 3.

The mean age ± SD of the 14 co-infected patients was 34.4 ± 17.7 years, with 7 (50%) being males. Fever was present in all patients, sore throat in 12 patients, cough in 7 patients, and headache and malaise in 6 patients. Four patients had not received any COVID-19 vaccine doses, whereas the remaining 10 had received at least two. None of the patients had an underlying immunodeficiency, and all cases were observed only after July 2022, coinciding with the emergence of Omicron and subsequent variants. None of the patients exhibited hypotension or hypoxemia.

Their mean ± SD [range] white blood cell count was 5,812.5 ± 660.0 [4,400–6,600]/µL, with neutrophil counts of 4,342 ± 911 [3,089–5,316]/µL, which were within normal or mildly elevated ranges. However, lymphocyte counts were reduced (954 ± 542 [180–1,401]/µL). Chest imaging was performed in five patients, with pneumonia detected in only one case. Three patients required hospitalization owing to difficulty in oral intake from pharyngeal pain, whereas the remaining 11 patients were treated as outpatients.

All patients improved clinically following antibiotic therapy, with nine receiving penicillin-based antibiotics, three receiving macrolide-based therapy, and two receiving cephalosporins. Additionally, five patients received antiviral therapy. None of the patients developed post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis or Long COVID-19.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the incidence of GAS-P before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and revealed that, as shown in epidemiological data, GAS-P significantly decreased after May 2020, with the loss of seasonal variation, followed by a resurgence from May 2023, particularly in younger age groups, coinciding with the re-establishment of its seasonal pattern. Similar to other upper respiratory tract infections, the incidence of GAS infections declined significantly in Japan following the outbreak of COVID-19 [

2,

6]. The level of

Streptococcus pyogenes infections decreased significantly by 0.324 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.06–0.589) during the pandemic [

2]. This reduction followed the World Health Organization’s declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic on March 11, 2020, and the state of emergency in Tokyo from April 7 to May 25, 2020 [

13]. During this period, extensive NPIs, including mask-wearing, hand hygiene, gargling, and social distancing, were widely implemented in the general population [

2,

13]. As a result, the incidence of GAS-P among both adults and children declined substantially owing to these infection prevention measures [

5,

14].

In Japan, GAS-P typically exhibits two seasonal peaks: one from winter to spring and another in summer, primarily attributed to child-to-child transmission during vacations and large gatherings [

15]. The increased incidence of GAS infections among children following the resurgence may be due to reduced exposure during the pandemic, which limited opportunities for immunity acquisition. After the relaxation of restrictions, GAS may have spread rapidly in pediatric populations with lower prior immunity [

16].

A resurgence of GAS infections was reported in Europe from September 2022 onward, potentially associated with concurrent influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) epidemics [

17,

18,

19]. Previous studies have indicated that preceding or co-infection with respiratory viruses, such as influenza, varicella, measles, and Epstein–Barr virus, can contribute to the development of GAS-P [

20,

21]. However, despite a major RSV outbreak in Japan in the summer of 2021 [

22,

23], no corresponding increase in GAS-P was observed. Additionally, the circulation of influenza virus in Japan had nearly disappeared between March 2020 and November 2022 [

24]. The resurgence of influenza from December 2022, followed by the relaxation of public health restrictions, including the lifting of mask mandates on March 13, 2023, preceded the resurgence of GAS-P in May 2023 [

25,

26].

Given this timeline, the delayed resurgence of GAS-P in Japan may have resulted from the prolonged implementation of infection control measures, which suppressed GAS circulation longer than in European countries.

A similar study from Italy, which analyzed 2,230 swabs over a six-year period (2018–2023) using antigen testing, reported epidemiological trends comparable to those observed in Europe. Despite being a single-center study, it documented a temporary decline in GAS-P cases, followed by a resurgence, aligning with our findings [

7].

One limitation of the Italian study was its insufficient investigation of viral co-infections. In contrast, we were able to analyze 14 cases of concurrent GAS-P and COVID-19, providing additional insights into the interaction between these infections. Our data demonstrated that co-infection occurred across all age groups and in both sexes. Furthermore, co-infection cases were observed predominantly during the summer and winter months, coinciding with periods of increased GAS-P and COVID-19 incidence.

A notable characteristic of these co-infection cases was the presence of fever and sore throat—common to both COVID-19 and GAS-P—along with headache, malaise, and cough, which are more typical of SARS-CoV-2 infection [

1,

27]. Laboratory findings showed that while total white blood cell counts and neutrophil levels remained within normal to mildly elevated ranges, lymphocyte fractions were frequently decreased. This contrasts with typical GAS-P, which is generally characterized by leukocytosis with neutrophilia and preserved lymphocyte counts, whereas absolute lymphopenia is rare [

28,

29]. The frequent lymphopenia observed in our co-infection cases may reflect the additive impact of SARS-CoV-2, as COVID-19 is known to cause lymphocyte depletion even in mild cases [

30]. This pattern supports previous reports indicating that viral-bacterial co-infections can lead to atypical immune responses in the upper respiratory tract, potentially altering expected laboratory findings.

Despite these immunologic alterations, no severe cases were observed in our cohort, suggesting that GAS–SARS-CoV-2 co-infections occurring in the post-Omicron period may generally follow a relatively mild clinical course [

8]. Nonetheless, several patients required hospitalization owing to severe pharyngeal pain and difficulty in oral intake, highlighting the need for careful clinical monitoring. All cases in our study responded well to antimicrobial treatment. The potential impact of co-infection on long-term complications, such as long-term COVID-19 or post-streptococcal immune-mediated disorders, remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

One possible explanation for the increased occurrence of co-infections since July 2022 is the high circulation of the Omicron variant in Tokyo during that period, which simply increased the probability of simultaneous infections. Another plausible mechanism is related to the upper respiratory tract tropism of Omicron, which may alter local infection barriers, such as bacterial adherence and effector cell-mediated clearance, thereby facilitating secondary bacterial infections, as has been reported with influenza viruses and other respiratory pathogens [

31,

32].

Virus-bacteria interactions remain a critical topic in infectious disease research. Earlier studies focused primarily on lower respiratory tract infections, as pre-Omicron SARS-CoV-2 strains primarily affected the lungs, leading to extensive research on secondary bacterial pneumonia [

33]. Severe cases of GAS lower respiratory tract infections have also been reported [

34]. However, with Omicron and subsequent variants, the oropharynx has become a key site for viral replication and persistence [

35]. While studies have examined interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and other upper respiratory tract pathogens, reports specifically addressing bacterial interactions in the pharynx remain limited. A 2023 study on upper respiratory tract microbiota suggested that COVID-19-induced lymphopenia may contribute to an increased risk of oropharyngeal Candida infections. However, the association between COVID-19 and GAS infections (including groups A, C, and G

Streptococcus) remains inconclusive [

36].

Our study provides indirect evidence suggesting a potential association between GAS and SARS-CoV-2 infections. Among 151 patients tested for both SARS-CoV-2 and GAS, 14 (9.3%) tested positive for both pathogens, indicating a relatively high co-infection rate. Notably, co-infection cases were identified even during periods when influenza and RSV were not circulating, and the peak of co-infections coincided with periods of increased SARS-CoV-2 and GAS-P transmission. These findings suggest a possible interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and GAS, warranting further investigation.

This study has some limitations. First, it only included a small number of patients, as it was conducted in a single center where the selection of relevant test relied on the judgment of attending physicians. In January and July 2022, a transient increase in the number of tests performed was observed due to difficulties in distinguishing sore throats caused by COVID-19 from those resulting from other conditions. Second, the inability to simultaneously perform GAS and COVID-19 PCR tests in all patients; hence, some patients with concurrent infections were overlooked. In the early stages of the pandemic, it was nearly impossible to perform these tests simultaneously owing to limited testing capacity. Test kits that can simultaneously measure both microorganisms were not available; when one test yields a positive result, further testing for overlapping infections is often omitted [

10].

Considering these diagnostic challenges, a substantial number of SARS-CoV-2 co-infections may have gone undetected. It remains unclear whether antibiotic monotherapy is sufficient or if antiviral therapy should be administered concurrently. Given this uncertainty, SARS-CoV-2 testing should be actively considered in patients with GAS infection who present with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, such as cough or lymphopenia.

5. Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of GAS-P significantly declined across all age groups, likely because of the widespread implementation of NPIs, which also disrupted its seasonal pattern. Following the relaxation of these measures, GAS-P resurged, particularly among children. Co-infections with GAS and SARS-CoV-2 may be underrecognized owing to limited testing. Although all observed co-infection cases in this study were mild, the potential impact of viral-bacterial interactions on disease severity and long-term complications remains unclear. Larger prospective studies are warranted to further investigate these associations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, HT.; methodology, HT, SS, Satomi F, and Suzuko F.; formal analysis, HT.; investigation, HT, SS, Satomi F, and Suzuko F.; resources, SS, Satomi F, and Suzuko F.; data curation, HT.; writing—original draft preparation, HT.; writing—review and editing, YS, SS, Satomi F, ST, Suzuko F, KP, NT, TY, HN, RH, MTK, SO, Miwa M, and Masaharu S.; visualization, HT, YS, and SS.; supervision, Suzuko F.; project administration, Masaharu S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Shinagawa Hospital (no. 22-A-14).

Informed Consent Statement

The research ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent by using the “opt-out method” of consent for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request due to restrictions such as privacy or ethical

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| GAS |

Group A Streptococcus

|

| NPIa |

Non-pharmaceutical interventions |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| RSV |

Respiratory syncytial virus |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Ashurst, J.V.; Edgerley-Gibb, L. Streptococcal pharyngitis.

- Kakimoto, S. Impact of the early phase of COVID-19 on the trends of isolated bacteria in the national database of Japan: an interrupted time-series analysis. J Infect 2023, 86, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McBride, J.A.; Eickhoff, J.; Wald, E.R. Impact of COVID-19 quarantine and school cancelation on other common infectious diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020, 39, e449–e452. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A, Zhang, L. Reduced incidence of acute pharyngitis and increased incidence of chornic pharyngitis under COVID-19 control strategy in Beijing. J Infect 2022, 85, 174–211.

- Boyanton, B.L. Jr.; Snowden, J.N.; Frenner, R.A.; Rosenbaum, E.R.; Young, H.L.; Kennedy, J.L. SARS-CoV-2 infection mitigation strategies concomitantly reduce group a streptococcus pharyngitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2022, 99228221141534. [Google Scholar]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Infectious Disease Surveilance Center. Available online: https://idsc.tmiph.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/diseases/group-a/group-a/ (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Massese M, Sorda ML, Maio FD, Gatto A, Rosato R, Pansini V, Caroselli A, Fiori B, Sanguinetti M, Chiaretti A, Posteraro B. Epidemiology of group A streptococcal infection: are we ready for a new scenario? Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 620–621.

- Lassoued, Y. Unexpected Increase in Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in Children After Respiratory Viruses Outbreak in France: A 15-Year Time-Series Analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofad188. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.H.; Veeraballi, S.; Ahmed, E. Ramy Yakobi, Jihad Slim. A case of co-occurrence of COVID-19 and group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Cureus 2021, 13, e14729. [Google Scholar]

- Khaddour, K.; Sikora, A.; Tahir, N.; Nepomuceno, D.; Huang, T. Case report: the importance of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and coinfection with other respiratory pathogens in the current pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020, 102, 1208–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Capilia™ Strep, A. Available online: https://www.tauns.co.jp/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/capilia_strep_a_Brochure_2007A.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and welfare. Clinical management of patients with COVID-19. Available online: https://www.niph.go.jp/h-crisis/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/20200706103735_content_000646531.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Nakamoto, D.; Nojiri, S.; Taguchi, C.; Kawakami, Y.; Miyazawa, S.; Kuroki, M.; Nishizaki, Y. The impact of declaring the state of emergency on human mobility during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2022, 17, 101149. [Google Scholar]

- Mettias, B.; Jenkins, D.; Rea, P. Ten-year prevalence of acute hospital ENT infections and the impact of COVID: a large population study. Clin Otolaryngol 2023, 48, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kennis, M.; Kung, V.M.; Montalbano, G.; Narvaez, I.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Vargas Barahona, L.; Madinger, N.; Shapiro, L.; Chastain, D.B.; Henao-Martínez, A.F. Seasonal variations and risk factors of Streptococcus pyogenes infection: a multicenter research network stidy. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2022, 9, 20499361221132101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frenck RW Jr, Laudat F, Liang J, Giordano-Schmidt F, Jansen KU, Gruber W, Anderson AS, Scully IL. A Longitudinal Study of Group A Streptococcal Colonization and Pharyngitis in US Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2023, 42, 1045–1050.

- Brechje de Gier. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal (Streptococcus pyogenes) infections (iGAS) in young children in the Netherlands, 2022. Euro Surveill 2023, 28, 2200941.

- Elvira Cobo-Vázquez. Increasing incidence and severity of invasive Group A streptococcal disease in Spanish children in 2019–2022. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023, 27, 100597.

- Nityanand Jain. Group A streptococcal (GAS) infections amongst children in Europe: Taming the rising tide. New Microbes New Infect 2023, 51, 101071. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, A.L. The association between invasive group a streptococcal diseases and viral respiratory tract infections. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 342. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, S. Pathogenic mechanisms of invasive group A Streptococcus infections by influenza virus–group A Streptococcus superinfection. Microbiol Immunol 2018, 62, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ujiie, M. Resurgence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections during COVID-19 Pandemic, Tokyo, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27, 2969–2970. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi, T. An atypical surge in RSV infections among children in Saitama, Japan in 2021. IJID 2022, 7, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Nagamatsu H, Yamada Y, Toba N, Toyama-Kousaka M, Ota S, Morikawa M, Shinoda M, Takano S, Fukasawa S, Park K, Yano T, Mineshita M, Shinkai M. Surveillance of seasonal influenza viruses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo, Japan, 2018-2023, a single-center study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2024, 18, e13248.

- Flu case numbers in Japan surge, signal epidemic beginning. Available online: https://themeghalayan.com/flu-case-numbers-in-japan-surge-signal-epidemic-beginning/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Japan relaxes mask guidelines in COVID milestone. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Japan-relaxes-mask-guidelines-in-COVID-milestone (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Akaishi, T.; Kushimoto, S.; Katori, Y.; Sugawara, N.; Egusa, H.; Igarashi, K.; Fujita, M.; Kure, S.; Takayama, S.; Abe, M.; et al. COVID-19-related symptoms during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant surge in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med 2022, 258, 103–110.

- Ashurst JV, Edgerley-Gibb L. Streptococcal pharyngitis. StatPearls. 2023.

- Pichichero, ME. Group A streptococcal infections. Pediatr Rev. 2016;37(10):403–415.

- Tan, L; et al. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:33. 28-30.

- Fan, Y. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: recent progress and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Piersiala, K.; Bruckova, A.; Starkhammar, M.; Cardell, L.O. Acute odynophagia: a new symptom of COVID-19 during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant wave in Sweden. Case Reports J Intern Med 2022, 292, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenath K, Batra P, Vinayaraj EV, Bhatia R, SaiKiran K, Singh V, Singh S, Verma N, Singh UB, Mohan A, Bhatnagar S, Trikha A, Guleria R, Chaudhry R. Coinfections with Other Respiratory Pathogens among Patients with COVID-19. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9, e0016321.

- Kawaguchi A, Nagaoka K, Kawasuji H, Kawagishi T, Fuchigami T, Ikeda K, Kanatani J, Doi T, Oishi K, Yamamoto Y. COVID-19 complicated with severe M1UK-lineage Streptococcus pyogenes infection in elderly patients: A report of two cases. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 148, 107246.

- Takahashi H, Morikawa M, Satake Y, Nagamatsu H, Hirose R, Yamada Y, Toba N, Toyama-Kousaka M, Ota S, Shinoda M, Mineshita M, Shinkai M. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 149, 107244.

- Boia ER, Huț AR, Roi A, Luca RE, Munteanu IR, Roi CI, Riviș M, Boia S, Duse AO, Vulcănescu DD, Horhat FG. Associated Bacterial Coinfections in COVID-19-Positive Patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 1858.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).