1. Introduction

The concept of sustainable finance has become a common place in the discourse of financial supervisors and institutions in recent years, largely due to the directives issued by the European Authority (ECB, EBA, European Commission). Undoubtedly, the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors is currently shaping a novel strategic perspective, a novel approach to business that is often termed “sustainable”. It is evident that European banks are currently engaged in the process of redesigning their business models; however, it should be noted that integrating ESG factors within the decision-making process will not be sufficient for the European financial sector.

The Islamic finance sector has attracted worldwide attention and has become increasingly well known. The emergence of the term “Islamic financial system” can be traced back to the mid-1980s. In the 1990s, the Islamic financial sector experienced remarkable expansion and recognition. This expansion was driven by the development of novel financial instruments by both Islamic and non-Islamic financial institutions and the adoption and utilisation of Shariah-compliant features, for example, al-Muddarabah and al-Muassasah by both Muslim and non-Muslim customers in their routine banking transactions (Zeti 2007). In recent years, the annual growth rate of the overall market has been estimated to have been between 15 and 20 percent. However, certain Islamic banks experienced accelerated growth in 2008 (Abd Razak and Abdul Karim 2008) due to the momentum created in the wake of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis (Mensi et al. 2020). According to S&P Global (2022), the Islamic finance sector is expected to grow at a rapid rate of 10 to 12 percent in 2021–2022. Notwithstanding the myriad peculiarities of the Islamic economy, Islamic banking is currently considered the defining feature of an Islamic economic system (Kuran 1995). In addition, Western banks, including HSBC and Standard Chartered Bank, have developed several financial innovations that adhere to the principles of syariah. This was done with the intention of capitalising on the growing market demand for Islamic investment products (Iqbal and Molyneux 2005).

Fundamentally, Islamic economics seeks to recognise and introduce an economic structure that adheres to the principles set out in the Islamic scriptures and the traditions of the Prophet (Abd Razak and Abdul Karim 2008). With a focus on Muslim nations, the industry has maintained its momentum to date, which is encouraging for further significant growth in the upcoming years (Global Finance 2024). Including the Islamic money and capital markets, this development has taken place in every sector of the Islamic financial system in Malaysia, including the Islamic banking and takaful industries. These include sukuk, takaful insurance, murabaha financing, and property funds and deposits structured along the principles of syariah. In addition, the variety of products and services offered has increased, which has led to increased competition in pricing and product design (Md Nor et al. 2016). With the introduction of more sophisticated Islamic financial products, such as investment-linked and structured products, the pace of product innovation has accelerated. Both pricing and product structure have become competitive for these products (Addury 2023).

Concurrently, cooperative banks are pivotal players in the European economy. They are similarly aligned with the principles of sustainability as Islamic banks would appear to be.

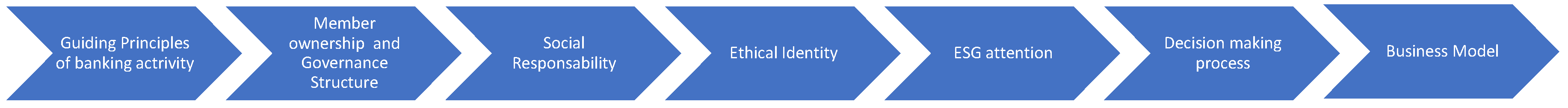

They facilitate access to finance at the local level and are pervasive even in remote areas of the continent. Cooperative banks are financial institutions that are owned and controlled by their members, who are also their customers. This model places emphasis on democratic governance (one member, one vote), the fostering of long-term relationships with clients, and a commitment to social values and environmental sustainability. Furthermore, the European cooperative movement has a longstanding tradition of responsibility and social cohesion, dating back to its inception in the nineteenth century. Such extensive networks frequently result in cooperative banks becoming the primary employers and taxpayers within their respective regions. Cooperative banks are particularly prominent in countries such as France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, where they contribute to financial stability and community development. It is typical for cooperative banks to reinvest profits back into the local community or into services for their members. This operational feature supports local development and stability. The objective of this paper is to to compare the business formulas of Islamic banks and cooperative banks. Both types of banks can be considered as banks with sustainable business models. The aim of the comparison is to identify similarities and differences between the two models. The methos of comparison used is represented in the Figure n.1 and is based on the following items which qualify the business formula of Islamic banks and cooperative banks: guiding principles of banking activity, member ownership and governance structure, social responsibility, ethical identity, ESG attention, decision-making process, business model. The final objective of this study is twofold: firstly, to identify the similarities and differences between Islamic and cooperative banks; and secondly, to provide a robust argument for the sustainability business model formula.

Figure 1.

A comparative analysis of the Islamic Bank and Cooperative Bank: analysis scheme.

Figure 1.

A comparative analysis of the Islamic Bank and Cooperative Bank: analysis scheme.

1.1. ESG Attention in European Banking System and Islamic Finance

The discrepancy between the ethical principles underpinning traditional finance and those that characterise Islamic finance has become a subject of mounting academic interest, particularly in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Islamic finance is frequently regarded as being more stable and balanced than traditional finance by virtue of its participatory system, which is predicated on ethical values and principles (Alawneh 2022). This stands in contrast to traditional finance, which is often the subject of criticism due to its prioritisation of individual utility and welfare, as well as the maximisation of shareholder value. Islamic finance is further distinguished by its foundation in a moral economy, which is predicated on the principles of social justice, economic growth, and the equitable distribution of resources (Alhammadi 2022).

The ethical foundation of Islamic finance is further reflected in its emphasis on sustainable development and social responsibility, which play essential roles in the Islamic financial and economic model (Farzoni & Allali 2018). The prohibition of riba (usury) is part of a wider ethical framework (Minhat and Dzolkarnaini 2016). Furthermore, Islamic finance is intended to assist the economically disadvantaged and vulnerable during periods of crisis, thereby reflecting its ethical and humanitarian principles (Khan et al. 2020). Islamic finance institutions apply ethical and society-friendly criteria in the management and administration of their affairs, further highlighting the ethical underpinnings of Islamic finance (Mathkur 2019).

Nevertheless, the issue of environmental and climate change considerations is not as prominent as it is in the European banking sector, where policymakers, regulators and investors are increasingly demanding that banks take environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into account in their lending decisions.

Conversely, traditional finance has been the subject of criticism for its perceived lack of ethical considerations (Castaldo et al. 2024), particularly in the context of the global financial crisis (Zanda and Castaldo 2023). The crisis resulted in the failure of numerous conventional banks and a surge in interest in the Islamic banking business model, which is predicated on ethical values and principles (Bourkhis and Nabi 2013). The claim that Islamic finance is more stable due to its ethical foundation is contested, but the emphasis on ethical and extra financial considerations in Islamic finance has led to suggestions that there are innate similarities between responsible finance and Islamic finance (Lai 2014; Richardson 2019).

In summary, the ethical framework of Islamic finance sets it apart from traditional finance, as it is rooted in moral and ethical principles, social justice, and sustainable development. This pronounced emphasis on ethics and social responsibility differentiates Islamic finance from traditional finance and has ramifications for financial stability and economic balance.

In recent times, the conventional modus operandi of the banking sector has been subject to scrutiny on account of the plethora of technical standards, guidelines, and principles promulgated by the European authorities regarding ESG considerations in the strategic planning and business model choices of banking institutions. The factors pertaining to the environment, society, and governance (ESG) are a source of growing concern for policymakers and regulators on a global scale. In general, supervisory authorities in the banking, insurance, and pension fund sectors are emphasising sustainability and ESG issues. The concept of sustainable finance has become a common place in the discourse of both supervisors and financial institutions.

ESG signifies a novel strategic perspective, a paradigm shifts in the modus operandi of conducting business, which is laudable and likely to yield favourable outcomes in the immediate future. However, it concomitantly engenders a novel configuration of risk (Engle et al. 2021).

A frequently cited framework that provides a more precise definition of ESG factors is the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing (UNPRI), which has been referenced in various reports and impact statements.

Environmental issues have been referred to as climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the environment's related risks (e.g. natural disasters). Positive environmental outcomes may be defined as the avoidance or minimisation of environmental liabilities, the reduction of costs and an increase in profitability through energy and other efficiencies, and the reduction of regulatory, litigation and reputational risk.

Social considerations have been linked to the rights of people and communities, as well as issues of inequality, inclusiveness, labor relations, and investment in human capital. The term 'social risks' refers to the impact that companies can have on society. These are addressed by corporate social activities, such as the promotion of health and safety, the encouragement of labour management relations, the protection of human rights, and the focus on product integrity. The positive outcomes of these efforts include enhanced productivity and morale, reduced turnover and absenteeism, and strengthened brand loyalty.

The concept of governance pertains to the internal management of companies. These issues encompass areas such as corporate brand independence and diversity, corporate risk management, and excessive executive compensation. Corporate governance activities, including the promotion of diversity and accountability within the board, the protection of shareholders' rights, and the reporting and disclosure of information, address these issues. Positive outcomes in the domain of governance include the alignment of interest between shareholders and management, as well as the mitigation of undesirable financial surprises.

However, the interpretation of the ESG single pillars is contingent upon the way they are determined whether they pertain to an ESG factor, an ESG issue, or an ESG risk. In the absence of a definitive EU definition of sustainability risk the prevailing understanding of ESG risk is that it signifies the risk of adverse financial consequences arising, either directly or indirectly, from the repercussions that ESG events may have on the financial institution and its key stakeholders, encompassing customers, employees, investors, and suppliers. It is important to emphasise that, in the current context, ESG attention is a novel strategic perspective, a novel approach to a business willing to self-identify as “sustainable”. The ESG factors are positively and strongly associated with company profitability for both financial and non-financial companies.

In this regard, the present study aims to “look inside” two sustainable native business models: the system of cooperative credit banks and that of Islamic banks. The specific research objective is twofold: firstly, highlight the differences between the two sustainable business models, and secondly, examine their impact on economic performance. The paper contributes to the extant literature by arguing that the sustainable business model is worthy of recognition and by offering suggestions to policymakers committed to defining rules and guiding principles in sustainable finance.

The initial section of the paper introduces the topic of the distinction between conventional and Islamic finance, with reference to the European perspective and the criteria of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. The subsequent sections are structured as follows: section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review of the fundamental characteristics of Islamic finance, its value system, and the value codes of Islamic banking organisations. Additionally, it provides an in-depth examination of the influence of sustainable models on the economic performance of Islamic finance. The third section of the paper presents a comparative analysis of the sustainability models of cooperative banks and Islamic banks. It considers decision-making processes and social responsibility, cultural aspects and governance structures, as well as the mission and vision of both types of banks. The section also offers some general conclusions, which will inform further research on this topic.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Banking and ESG Factors

The integration of ESG risk considerations into planning, strategic development, and business model formulation represents a substantial challenge for both financial and non-financial enterprises. Conversely, it can also be regarded as a potential catalyst for enhancement, with the ability to boost economic performance, enhance the value of shares on the equity market, augment funding capacity, and bolster the overall reputation of the company in relation to its various stakeholders, thereby influencing the risk profile. The relationship between ESG and performance has been a subject of extensive research in recent literature. The extant literature on ESG has made significant contributions, endeavouring to comprehend the impact of ESG considerations on firm performance, or more precisely, the nature of the relationship between ESG performance and value creation. Nevertheless, only a limited number of studies have focused on financial intermediaries (Simpson and Koers 2002; Malik 2015; Fayad, Ayoub, and Ayoub 2017; Maqbool and Zameer 2018). In their study, Brogi et al. (2022) examined the potential of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) awareness in a business model to serve as a credit risk mitigation factor. The researchers investigated and compared the ESG issues in industrial and financial companies. Concurrently, other scholars have conceptualised a theoretical model for a novel scoring model for ESG disclosure in banking institutions. The primary outcomes from their preliminary testing underscore the imperative for financial institutions to promote awareness “regarding social issues, particularly those pertinent to local communities” (Gai et al. 2023).

2.2. Basic Principles of Islamic Finance and Value System Related with Islamic Finance

Islamic finance is distinguished by its fundamental principles and values, which set it apart from conventional finance. These principles are rooted in Islamic law (Shariah) and ethical values, emphasising cooperation, social justice, and spiritual considerations. Operating on the principles of mutual sacrifice and cooperation between the borrower and the lender, Islamic finance aims to fulfil basic needs (Amin et al. 2014). It is a financial and economic model that integrates sustainable development and social responsibility as essential components (Farzoni & Allali 2018). Conversely, Islamic finance prioritises values such as profit-loss sharing, real asset backing, and risk-sharing, as opposed to the conventional finance approach of prioritising individual utility maximisation (Alamad 2024). The fundamental principles of Islamic finance are rooted in Shariah law, which prohibits the practice of interest (riba, Hidayatullah et al. 2024). In its stead, Islamic finance advocates for profit and loss sharing, where risks and rewards are distributed between parties (Khalifah et al. 2024). Equity-based financing and profit and loss sharing are regarded as the optimal financing methods in Islamic banking, reflecting the emphasis on cooperation and shared prosperity (Khalifah et al. 2024). Moreover, Islamic finance upholds principles of honesty, fairness, and transparency in financial transactions (Akhlaq and Asif 2024). Islamic finance also places a strong emphasis on ethical governance and corporate social responsibility. Shariah governance frameworks guarantee the legitimacy of financial instruments and cultivate stakeholder trust within the Islamic finance industry (Akhlaq and Asif 2024). The ethical dimension of Islamic finance introduces a unique perspective that aligns with principles of social responsibility and sustainability (Hassanein and Tharwat 2024; Tlemsani and AlSuwaidi 2016). The ethical identity of Islamic banks is characterised by their commitment to interest-free transactions, transparency, and social responsibility (Rahman et al. 2014).

In summary, Islamic finance is guided by the principles of Shariah law, cooperation, social justice and ethical values. Islamic finance can therefore be regarded as an alternative financial system that prioritises shared prosperity, risk-sharing and ethical conduct, distinguishing it from conventional financial models. This ethical framework has been shown to help mitigate agency problems, as Islamic banks are less likely to engage in self-interested behaviours that could harm their stakeholders (Zainuldin et al. 2018).

2.3. Impact of Sustainable Islamic Models on Economic and Financial Performance of Islamic Finance

Islamic finance demonstrates specific performances influenced by various factors. Research has demonstrated that profitability, measured by return on equity (ROE), exerts a significant influence on the financial performance of Islamic banks (Kismawadi 2024). Furthermore, corporate governance has been demonstrated to play a critical role in moderating the impact of different financing types on the financial performance and risk of Islamic banks (Rashid et al. 2024). Furthermore, market structure variables have been found to impact Islamic banking performance in both the short and long term (Saâdaoui & Khalfi 2024). Furthermore, Islamic bank financing has been demonstrated to exert a favourable influence on the performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (Khan et al. 2024). The contribution of Islamic banking to the real economy has been attributed to the effective performance of Islamic financial institutions (Meskovic et al. 2024). The impact of financing risk, bank capital, operating costs, inflation, and other factors on Islamic banking performance has also been emphasised (Efendamara et al. 2024). Furthermore, Islamic finance has been observed to enhance business performance due to variances in underlying structures and business norms compared to conventional finance (Simsek et al. 2024). The relationship between Islamic financial literacy and decision-making in Islamic banking financing, and its impact on business performance, has also been explored (Habriyanto et al. 2022). Moreover, studies have examined the determinants of Islamic performance ratios, such as financing quality and return on asset ratio (Nugroho et al. 2020). To summarise, the principles of Islamic finance have a significant impact on profitability, corporate governance, market structure, funding plans and risk management practices.

The relationship between organisational identity, which stems from a strong ethical connotation, disclosure and the performance of Islamic banks appears to be well established (Hassan 2017). Ethical identity disclosures, which include the communication of ethical practices and commitments, are vital for building stakeholder trust and enhancing the institution's reputation (Mutmainah 2023). In the context of Islamic banks, such disclosures not only reflect adherence to ethical standards but also serve as a differentiating factor from conventional banks, thereby reinforcing their unique identity in the financial sector (Prativi et al. 2021). A strong organisational identity helps to align a bank's strategies with its core values and vision. This alignment makes it easier for the bank to focus on its goals and pursue initiatives that are consistent with its identity. Specifically, organisational identity plays a significant role in employee morale and engagement. When employees strongly identify with their bank's values and mission, they are more likely to be motivated, productive, and committed to achieving organizational goals, it also influences how a bank responds during crises, whether they are financial, regulatory, or reputational. how investors, regulators, and other external stakeholders perceive the bank. A bank with a clear, trustworthy identity is more likely to attract investment, comply with regulatory standards, and maintain positive relationships with external parties. These external factors can directly influence the bank's financial performance, stock value, and ability to access capital.

A comprehensive understanding of these dynamics is imperative for enhancing the performance and stability of Islamic financial institutions.

3. Comparison Between Cooperative Bank and Islamic Banks Sustainability Models

Cooperative banks are defined as local and proximity banks that foster self-help, responsibility and solidarity. These institutions comply with the banking and cooperative legislation of their respective countries, with the key principle of one person equal one vote. Furthermore, these banks emphasise the common good of society.

The objective of this section is to comprehend the sustainability of a cooperative bank's business model, the efficacy of its ESG orientation from a regulatory standpoint, and the distinctions between cooperative banks and Islamic banks. To this end, a comprehensive analysis of the structural and organisational characteristics of European cooperative banking systems and their founding values is warranted, with a view to gaining a more profound understanding of their concept of sustainability.

Islamic banks, on the other hand, emphasise social responsibility and ethical behaviour, aligning financial activities with moral and ethical values. They are rooted in Shariah law and guided by ethical and moral principles derived from Islamic teachings. The cooperative banking model has a long history, with its origins dating back to 1849 in Germany when Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen established the first cooperative banking institution in Europe. From its inception, the fundamental objective of these financial institutions has been to extend financial support to the "excluded" and the weakest sections of the population. The social democratic function of cooperative banks is derived from the legal system; they are inspired by cooperative democracy, since it is forbidden for this company to deviate from the per capita vote and to elect. In 2021, cooperative banks managed over 9.4 trillion euros in assets and served approximately 225 million customers across Europe. These institutions employ approximately 712,000 individuals and operate over 36,500 branches (EACB 2021).

Cooperative banks are a prominent example of market leaders in the domain of socially responsible investment (SRI) products, encompassing funds and savings accounts. This system is comprised of entities that differ from legal and organisational perspectives, as well as in terms of governance models and stakeholder relationships. Despite the wide articulation and differences, the system is united by “a deep interconnection between the typical functions of intermediaries and the social function, thanks to a “formula” that includes proximity to the territory (via their wide network of branches), solidarity and responsible resilience in the context of belonging; a strong commitment to social responsibility, the solid share of the domestic retail market, fighting against exclusion, social and environmental concerns, resilience, proximity, trust and governance” (EACB 2019)

1.

Customers and members of cooperative banks are represented in the bank’s governance structure through participation on boards and membership councils; thus, ensuring the members’ interests which are important objectives in the bank’s strategic plans. Democratic governance manages the cooperative banking system. This is ensured by limiting the share held by each shareholder and through per capita voting (one person, one vote), while the profit motive is excluded by restrictions on distributing profits (as noted above) by the principle of the indivisibility of reserves. As the capital of cooperative banks are contributed by their clients, is not listed on the stock exchange. Neither subject to the pressure of listing the associated risks (takeover bids), it remains focused on the expectations of its members and can more easily encourage long-term thinking. A long-term approach stems from the interest of the member and the community in maintaining access to the bank's services over time’. The long-term vision towards sustainable success is also expressed in adherence to UN Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda, specifically: Goals 1(No poverty - 1.4 devices for fragile clients and microcredit); 7(Affordable and clean energy - 7.2. (Financing renewable energies); 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth - 8.3 Development of micro-enterprises and SMEs); 13 (Climate Action - 13.3 Financing the energy transition); 17 (Partners for the Goals- 17.7 Financing the social economy). These goals are not only embedded in the vision, but their pursuit is also supported by the specific characteristics of co-operative bank governance.

By following the principle of serving local communities, cooperative banks are also local since their members represent the environment in which the company operates, and the deposits collected are used to support and finance the development of real economy, thus creating a geo-circular economy. Cooperative banks grant proximity to their clients; they usually try to provide credit to their clients and members in good and bad times. They are key players in financing the real economy, the households, and the SMEs, supporting territories and local communities.

The mutual benefit spreads through the pursuit of long-term financial objectives, including offering shareholders their products/services at “advantageous” market terms. Compared to other banks, the person, the commonwealth, and solidarity are always at the center of the activities of cooperative local banks. Cooperative banks are among the market leaders for SRI products such as funds and savings accounts. The cooperative bank’s business model is “of proximity”, “people/community-focused” but how is sustainable in the regulatory view? What is the difference with Islamic finance?

3.1. Decision-Making Processes and Social Responsibility Between Cooperative Bank and Islamic Banks

Although cooperative banks and Islamic banks have different operational structures and frameworks, both share common ideas of social responsibility and community welfare. Despite these differences, both cooperative and Islamic banks share a commitment to ethical finance and stakeholder engagement. This is reflected in their decision-making processes, which prioritize the interests of the community and society, rather than just the interests of the bank itself.

Cooperative banks have a unique structure that aligns with their original objectives. This structure offers consumers the opportunity to become owners, depositors, and borrowers of the bank (Gulzar et al. 2021). Additionally, cooperative banks operate under democratic governance based on the "one member, one vote" principle. This framework allows members to participate directly in the decision-making process of the bank. As a result, the democratic model ensures that transparency and fairness are maintained in all aspects of the bank's operations. A participatory approach is often included in the bylaws of a bank and can be seen in activities such as annual general meetings. During these meetings, members could vote on important matters such as board elections, dividend distributions, and strategic directions (European Association of Co-operative Banks 2020).

According to Borzaga and Santuari (2001), the role of cooperative banks is to foster economic democracy and empower local communities through inclusive decision-making processes. For instance, cooperative banks usually do not face the problem of selecting borrowers unfairly, as members have a personal stake in the bank's success and use their local connections and knowledge to decide which community member is eligible for loans. Moreover, borrowers are less likely to default on their loans, as doing so would jeopardize their ownership stakes, deposit holdings, and social and business relationships with other members (Fonteyne and Hardy 2011). Hence, this participatory approach aligns with their ethos of social responsibility, as cooperative banks aim to serve the needs of their members while promoting financial inclusion and sustainable development. According to Diaconu and Tiluita (2020), the corporate governance plan of cooperative banks consists of regulations and principles aimed at improving transparency and fairness in decision-making by governing bodies to enhance economic performance and value.

Thomas A. (2004) emphasises the contribution these associations have made towards broadening the concept and standard parameters of volunteer organisations, providing basic social welfare services, and integrating the disadvantaged into the mainstream of society (Thomas 2004). The paper emphasises the numerous traditional and advantageous business features, the straightforward access to financial instruments and the capacity to initiate broader social projects. On the other hand, Islamic banks adhere to Shariah rules, which prohibit interest and favor profit-sharing structures based on shared risk and reward (Alam 2024). Decision-making in Islamic banks is guided by Sharia boards comprising of religious scholars and financial experts who ensure compliance with Islamic law (Faizi 2024). Iqbal and Mirakhor (2007) highlight the importance of Shariah governance mechanisms in maintaining the integrity and legitimacy of Islamic banking activities. In 2003, additional measures were introduced that required Islamic banks to establish a nominating committee, remuneration committee, and risk management committee. These committees strengthen the role of shareholders in overseeing the effectiveness of the board of directors and management. This structure enhances the integrity of decision-making processes in Islamic banks.

Despite having different organizational structures, both cooperative banks and Islamic banks prioritize social responsibility. As community-oriented financial institutions, cooperative banks focus on activities that benefit both their members and the communities they serve. This includes providing affordable financing, supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and promoting financial awareness and education (EACB 2020). In this context, the initiatives of social responsibility in cooperative banks aim not only to invest in communities but also to fulfill specific obligations within various activities, including consumer relations, employee well-being, and supply chain duties (Diaconu and Tiluita 2020). On the other hand, social responsibility in Islamic banks is based on Sharia law that prohibits usury, gharar, (uncertainty, hazard, chance or risk) environmental destruction and puts more emphasis on moral and ethical behavior (Di Bella and Al-Fayoumi 2016; Dusuki 2011). For instance, Islamic banks engage in socially responsible financing, including Zakat (charitable giving), Waqf (endowments), and Sadaqah (voluntary contributions) to support impoverished communities (Farook et al. 2011) and employees (Jusoh et al. 2015; Dusuki 2011).

For cooperative banks’ organizational identity influences their approach to disclosure. As we reveal their mission to serve members and the community, it shapes how they present themselves and communicate with stakeholders. The emphasis is consistent on social impact, cooperative banks with a strong community development identity can provide detailed information on their social, environmental and economic contributions.

This would include information on loans to local businesses, sustainability projects and investments in low-income neighborhoods.

Transparency towards stakeholders is also an integral part of the organisational identity of the cooperative bank. As cooperatives are member-owned, they can disclose more information about how profits are distributed among members, democratic decision-making processes, and any initiatives to increase member engagement. Transparent disclosure practices reinforce this identity. Disclosures on risk management, governance, and decision-making processes can support the bank's identity as a responsible, member-focused organization. While cooperative banks are committed to transparency, their identity as member-oriented institutions means they may selectively disclose information in ways that align with member interests.

The relationship between organisational identity and disclosure in cooperative banks is therefore particularly important and is characterised by reciprocity due to its strategic connotation and its nature that links it to organisational identity. The identity of a co-operative bank as a member-centered institution, and a community-centered ethos, strongly shapes its approach to disclosure. Transparent and ethical disclosure methods reinforce this identity, helping to build trust, demonstrate accountability and foster a sense of ownership among members.

Ultimately, we can assert that the way a cooperative bank discloses information can strengthen or weaken its organisational identity, making it a key tool for maintaining credibility and supporting the long-term sustainability of the cooperative model.

Although cooperative banks aim to focus on community welfare, they also face challenges in striking a balance between social duty and financial sustainability. They often compete with larger commercial banks while still trying to prioritize their commitment to the community (EACB 2020). Similarly, Islamic banks must comply with intricate Shariah standards while also managing conflicts that may arise between profitability and social goals (Iqbal and Mirakhor 2007). However, Islamic banking adheres to the principle of a balance between profit and social welfare for society. Therefore, social responsibility activities in Islamic banking are expected to follow ethics based on Islamic principles, such as conducting legitimate transactions and prohibiting usury and speculation in business transactions.

3.2. Cultural Aspects and Governance Structures Between Cooperative Bank and Islamic Banks

The primary distinguishing feature of cooperative or mutual banks is that they are predominantly owned by their clientele via non-negotiable instruments (Fonteyne and Hardy 2011). In this structure, owners are granted member shares that are non-tradable but redeemable (Gulzar et al. 2021). Typically, depositors receive a minimum of one share, which can only be redeemed by closing their account. Additionally, shares may be available for purchase and redemption under specific conditions. These shares serve as a form of control over the bank's management. This framework enables the establishment of diverse organisational structures and control procedures within the cooperative bank (Al-Muharrami and Hardy 2014). Another salient feature is its democratic governance, which operates on the principle of 'one member, one vote' (Gulzar et al. 2011). This ensures that every member has an equal voice in decision-making, regardless of the amount of equity they hold in the bank's deposits and loans. The notion of autonomy is established based on the governance structures' ability to provide sufficient oversight and supervision for managers (Lamarque 2018). Finally, the principle of accountability is applied to cooperatives' interactions with both customers and employees/managers, whereby it is practised by listening, providing help, and establishing relationships.

On the contrary, several scholars highlighted that one of the issues that arises while assessing the efficacy of democratic governance in such banks is members' commitment to the institutions (Stenfancic et al. 2019). It is not always clear if such members have the necessary incentives to actively participate in decisions on bank strategies and policies, and this problem has received little attention in the economic literature (Ferri et al. 2015). A study on the complex governance of cooperative banks indicated that voting during general assemblies is a mechanism for direct control over top managers (Alexopoulos et al. 2013). However, little information was provided on the level of participation of bank members in general meetings, which may ultimately lead to poor investment strategies by cooperative banks, especially the larger ones.

Meanwhile, Butzbach and von Mettenheim’s (2014) seminal work posited that cooperative banks possess an external disciplining mechanism through networks, in the form of second-tier organisations that provide auditing and monitoring activities for local cooperative banks. Through joint-liability and cross-guaranteed schemes, these organisations can monitor management's fraudulent activity, such as the misuse of the banks' available cash flows. This enhances the stability and efficiency of cooperative banks by offering economies of scale and mitigating risks associated with their limited size and homogeneous customer base. As previously stated, Islamic banks operate in accordance with the tenets of Sharia law, which governs all aspects of Islamic finance. Siddiqui (2006) posits that Islamic principles serve as the foundation for the cultural ethos of Islamic finance, which places a strong emphasis on fairness, ethical conduct, and social welfare. To ensure Shari'ah compliance, financial investments must be linked to a "real" action, whereby the provision of a good or service does not involve financial investment (Al-Muharrami and Hardy 2014). Hence, the prohibition of interest rate (riba') based on the idea that a fixed return that changes only in rare cases like bankruptcy would not be linked to any actual economic activity. Trading financial instruments, including derivatives, for profit is illegal. However, forward contracts are permitted. Profit and loss sharing are essential principles in Islamic finance, where providers (lenders) must participate in the business's risks to receive a benefit. In this context, lenders should share the entrepreneur's risk to receive profits from their investment (Tok and Yesuf 2022). The objective of Islamic banks and financial institutions is to cultivate moral and spiritual advancement, rather than to prioritise the generation of profits.

Islamic banking is distinguished by its comprehensive approach to economic and socioeconomic dimensions, a departure from the conventional banking industry's predominant focus on financial returns (Parashar 2010). The Islamic banking model is predicated on business association and partnership, thus helping to eliminate the unjust acts of the diverse stakeholders created by the interest-based banking system (Javed et al. 2013; Masruki et al. 2011). Moreover, Islamic banking products are founded on principles of trust and community-centeredness. Given that the interests of stakeholders in Islamic financial institutions (including Islamic banks) differ from those in conventional institutions, it is essential to clearly define the corporate governance structure to meet the needs and rights of stakeholders based in Islamic financial institutions. One of the ongoing governance efforts in Islamic banks is the formation of a Shariah board (SB), which is comprised of Islamic experts in jurisprudence with sufficient knowledge of contemporary finance to assure continued conformity with Shariah regulations. SB functions as an additional layer of governance, promoting enhanced transparency within the Islamic banking sector (Hassan et al. 2017; Nomran et al. 2018). The role of the SB encompasses several functions, including the certification of new financial products, the conduct of Shariah audits, the calculation of zakat, the distribution of non-compliance income, and the guidance of banks on their social responsibilities. The role of SB can be considered the foundation of Islamic banking. The overarching objective of SB is twofold: firstly, to uphold the legitimacy of the Islamic financial industry and, secondly, to enhance stakeholder confidence in Islamic banks' products and services (Khan et al. 2024). The governance structure of Islamic banking, which adheres to Shariah-compliant principles and is closely monitored and guided by the Sharia Boards, distinguishes it from conventional banking (Khan et al. 2024). Achieving Islamic corporate governance entails safeguarding stakeholders' interests through the principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents a comparative analysis of two Islamic banks and two cooperative banks. Both the Islamic and cooperative banks are examined in terms of their configurability as banks with sustainable business models; and in this perspective we analyses the business formula of Islamic banks and cooperative banks in relation to different items: guiding principles of banking activity, member ownership and governance structure, social responsibility, ethical identity, ESG attention, decision-making process, business model.

The main results are shown in the table below (

Table 1).

Where the results in the table are similar, their respective origins diverge. In one case, it is the regulatory framework that is changing, while in the other it is the application of Sharia law.

In conclusion, cooperative banks represent the concepts of cooperation and democratic governance. Cooperative banks embody the principles of cooperation and democratic governance, serving as vital financial institutions that prioritise members' interests over profit maximization. Their unique governance structure is characterised by member ownership and participation, which distinguishes them from conventional banks. This democratic framework aims to ensure that all members have a voice in the decision-making process, reflecting the cooperative ethos of mutual aid and shared benefits (Maroua 2015; Stefancic et al. 2019).

Islamic banks incorporate Shariah principles into their cultural ethos and governance structures. Understanding these cultural characteristics and governance frameworks is essential to understanding the organisational dynamics and decision-making processes of these different banking models. The effectiveness of this governance model can be undermined by various challenges, including member engagement and the complexity of the modern banking environment (Stefancic 2011).

In an organisation, harmony and unity of purpose develop when the decisions and actions of the various members are directed and coordinated towards a general unifying purpose (Zanda and Castaldo 2023). Effective governance is based on integrated knowledge management, where access to and sharing of information leads to informed and transparent decisions for the common good (Castaldo and Gatti 2020).

It seems reasonable to argue that the establishment and maintenance of a functional cooperative system depends on the consent of its constituent members. Furthermore, it can be posited that formal authority is contingent upon 'acceptance' (Zanda 2017). Cooperative banks have played a pivotal role in promoting financial inclusion, often serving as the only accessible financial institution in certain regions (Rosa and Pawłowska 2023). Their focus on local needs and community development is in line with the cooperative principles of self-help and solidarity, which are essential for promoting economic resilience and social cohesion (Giagnocavo et al. 2012). However, despite their fundamental principles, cooperative banks face significant governance challenges. Issues such as member apathy and the concentration of decision-making power, for example, can undermine the democratic principles on which they are based (Jardat et al. 2010; Stefancic et al. 2019). It can therefore be concluded that the success of cooperative banks depends not only on their commitment to cooperative principles, but also on their ability to overcome internal challenges related to governance and active member participation. Cooperative banks are local and proximity banking organisations that foster self-help, responsibility and solidarity. They comply with the banking and cooperative legislation of their respective countries and emphasise the common good of society. Islamic banks, in contrast, prioritise social responsibility and ethical conduct, aligning financial activities with moral and ethical values. The establishment and sustenance of a functional cooperative system hinges on the consensus of all its constituents. The legitimacy of formal authority is contingent upon acceptance. The success of cooperative banks is contingent upon their capacity to surmount the dynamics of internal challenges about governance and member involvement. It has been established that both models are characterised by a predominant organisational identity. Within the context of ethical banking, this identity is a multifaceted construct encompassing the values, beliefs and ethical principles that guide the operations and interactions of financial institutions.