1. Introduction

In recent years, semiconductor materials based on tungstates and molybdates have been extensively studied due to their remarkable optical, electronic, and photocatalytic properties [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among them, cadmium tungstate (CdWO

4) and cadmium molybdate (CdMoO

4) stand out for their crystal structures, which favor light absorption and charge transport, making them promising materials for applications in sensors, optoelectronic devices, and heterogeneous photocatalysis [

5,

6].

CdWO

4 crystallizes in a monoclinic Wolframite-type structure, characterized by edge-sharing WO

6 octahedral chains, with Cd

2+ cations occupying distorted coordination sites [

7]. This configuration results in efficient scintillation properties, with blue-white light emission under X-ray or γ-ray excitation, making it widely used in radiation detectors. In contrast, CdMoO

4 typically adopts a tetragonal Scheelite-type structure, where Mo

6+ ions occupy tetrahedral coordination sites surrounded by oxygen atoms [

8]. This structure enhances its photoluminescent properties and allows for structural modifications through doping, enabling the development of optimized materials for various applications.

The combination of these materials in the form of CdWO

4/CdMoO

4 heterostructures is an attractive strategy for optimizing their properties. These structures enhance charge carrier separation, reduce electron-hole recombination, and expand spectral response, contributing to improved efficiency in technological applications [

9]. The integration of CdWO

4 and CdMoO

4 in heterostructures leverages their complementary properties, particularly in photocatalysis and optoelectronic devices. The interface between these compounds facilitates the formation of a heterojunction that optimizes charge separation and transport, thereby increasing efficiency in technological applications [

10]. The synthesis of these heterostructures can be achieved through various techniques, including solvothermal methods, atomic layer deposition (ALD), and microwave-assisted techniques [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The choice of synthesis method directly influences the morphology and final properties of the material, making it a crucial factor in the development of optimized applications.

In this study, we will investigate the optoelectronic properties of CdWO4 and CdWO4/CdMoO4 heterostructures, where the CdMoO4 content will vary by 10, 20, and 30 mol% relative to CdWO4. The synthesized materials will be characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and photoluminescence (PL). The photocatalytic properties will be evaluated through the degradation of methylene blue dye.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental procedure was performed using Cd(NO3)2.4(H2O) (Êxodo, P.A.), Na2WO4.2(H2O) (Alfa Aesar, 95%), Na2MoO4.2(H2O) (Alfa Aesar, 98%), NH4OH (Cia Vicco, P.A.), and deionized water como precursores.

Initially, Cd(NO3)2.4(H2O) e Na2WO4.2(H2O) were added in a 1:1 ratio to a beaker containing deionized water and kept under constant stirring. After complete dissolution, ammonium hydroxide was added until the solution reached pH 8. The solution was then transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and irradiated with microwaves for 1 h at 140 °C under an internal pressure of 2 bar. At the end of this process, the supernatant was washed, separated by centrifugation, and dried in an oven at 100 °C. Similar procedures were performed, varying only the amount of Na2WO4.2(H2O) replaced by Na2MoO4.2(H2O) at molar ratios of 10, 20, and 30%. Finally, the samples were named according to the amount of Na2MoO4.2(H2O) added during synthesis, as follows: 0Mo, 10Mo, 20Mo, and 30Mo.

X-ray diffraction was used to identify the crystalline phases. The analysis was performed using a Shimadzu XRD-7000 diffractometer with CuKα radiation (1.5418 Å), scanning angles from 10° to 120°, a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning speed of 1°/min. Raman spectroscopy was conducted in the 100–1200 cm-1 range using a 532 nm laser with a power of 1 mW. Measurements were taken with a 15 s acquisition time on a LabRam HR Evolution confocal microscope from HORIBA Scientific. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy was performed using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer in diffuse reflectance mode, with a wavelength range of 200–900 nm. The reflectance data were converted into absorption using the Kubelka-Munk function [

16], and the Wood and Tauc equation [

17] was applied to estimate the bandgap (Egap) of the synthesized powders. The morphology of the synthesized samples was analyzed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) on a Carl Zeiss Supra 35 – VP microscope. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were carried out using a Cobolt/Zouk laser with an excitation wavelength of 335 nm. The sample power was set to 100 µW, and the detection system comprised a 19.3 cm spectrometer equipped with a silicon CCD detector (Andor – Kymera/Idus).

The photocatalytic activity of the samples was evaluated using methylene blue (MB) dye at pH 5 and a concentration of 10-5 mol.L-1 under UV-Visible radiation. For this, 0.05 g of the samples was added to 50 mL of MB solution and kept under constant stirring. After 20 min of stirring, a 2 mL aliquot was collected and compared to the initial dye absorption to assess the adsorptive capacity of the samples. Following this initial measurement, the six UVC lamps (TUV Philips, 15 W) in the reactor were switched on, and additional aliquots were collected every 20 min to evaluate the photocatalytic performance.

The absorbance of the collected aliquots was measured using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. The points of greatest intensity in the absorbance curves were used and the C/Co curves were plotted.

3. Results and Discussion

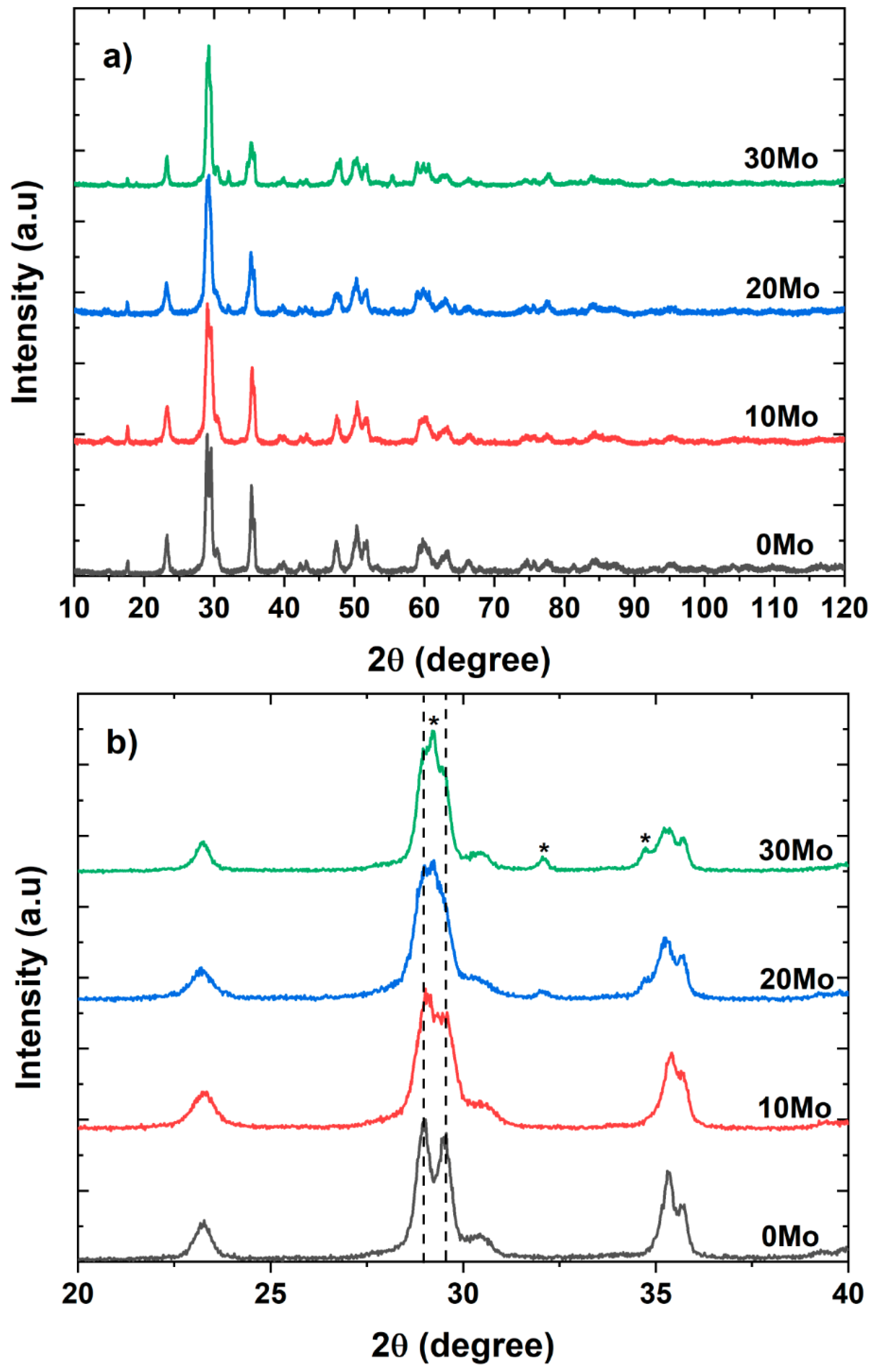

Figure 1a shows the diffraction patterns obtained for the pure sample and the CdWO

4/CdMoO

4 heterostructures. The 0Mo sample exhibits all the peaks corresponding to CdWO4, which has a Wolframite structure and belongs to the P2/c space group, as characterized by ICSD card 84454.

Figure 1b presents a magnified section of the diffraction pattern from

Figure 1a, highlighting the main peaks of the Wolframite phase. From

Figure 1b, it can be observed that as the molybdenum content in the solution increases, peaks associated with CdMoO

4 appear. CdMoO

4 has a Scheelite structure and belongs to the I41/a space group, as characterized by ICSD card 84455. These results indicate that the microwave-assisted hydrothermal method is effective in obtaining CdWO

4/CdMoO

4 heterostructures easily and simultaneously, without the formation of secondary phases.

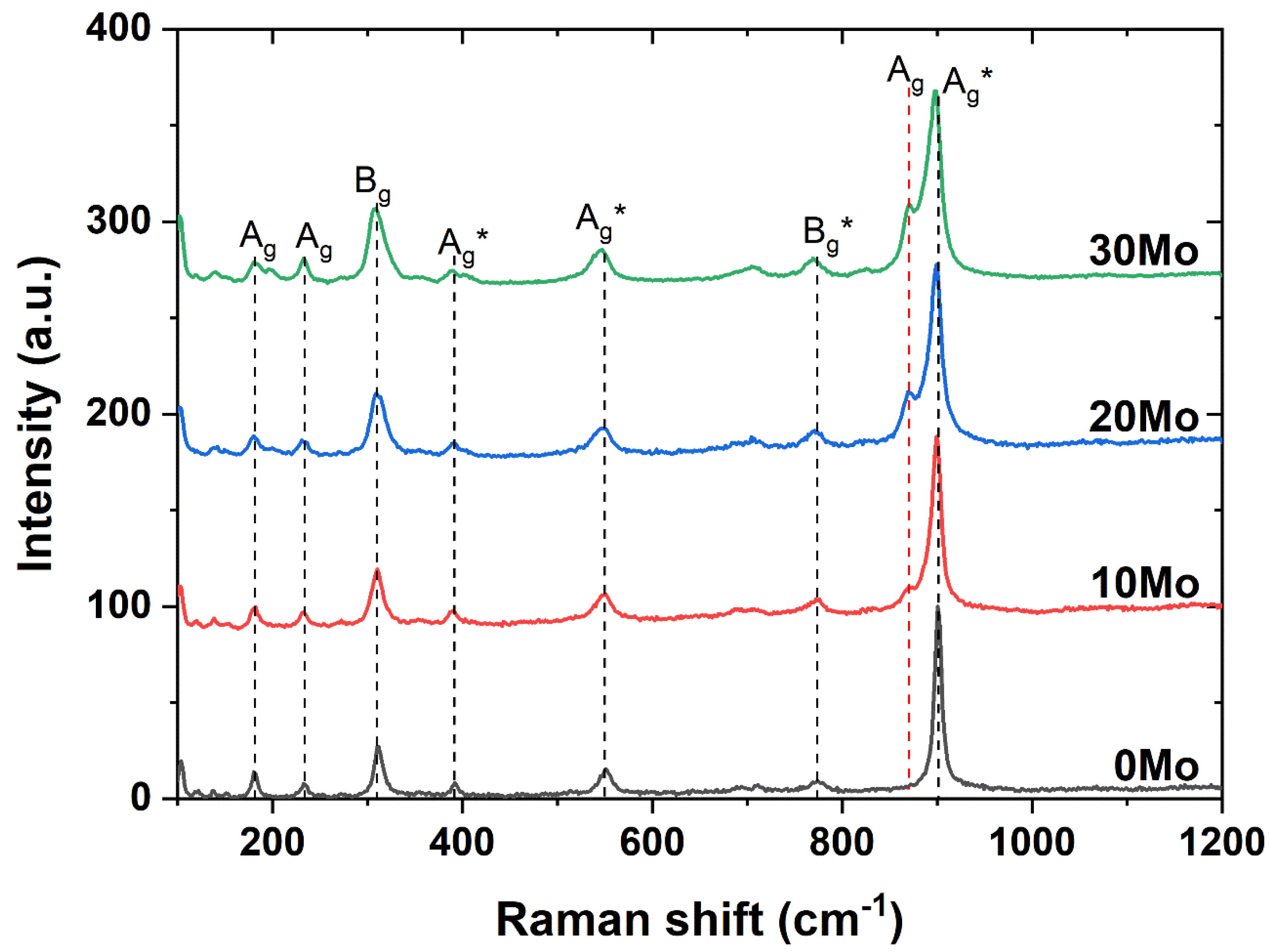

Other information about the synthesized materials was obtained through Raman spectroscopy.

Figure 2 presents the Raman spectra of the samples synthesized in this study. As previously discussed, CdWO

4 has a monoclinic Wolframite structure. The main vibrational mode (Ag*) of this phase is located near 901 cm

-1 and corresponds to the internal vibration of the WO

6 octahedron, which can be attributed to the symmetric stretching mode [

7]. Around 311 cm

-1, here is the B

g symmetric stretching of the CdO

6 octahedron. The Ag* vibrational bands near 393 cm

-1 are associated with weak modes of the [MoO4] tetrahedron, while the Ag* vibrational bands near 550 cm

-1 are associated with the mode resulting from the W-O-W symmetric stretching mode [

18]. The Bg* vibrational bands around 773 cm

-1 correspond to the symmetric stretching mode in relation to the center of symmetry. The Ag bands between 182 and 235 cm

-1 are the translational and rotational modes associated with the [MoO4]-2 tetrahedra and the Cd-O motion [

19]. As seen in

Figure 2, at a molybdenum proportion of 10%, the appearance of the Ag vibrational band around 870 cm

-1 is observed. This band is attributed to the symmetric stretching of the [MoO

4]

-2 tetrahedral clusters [

20].

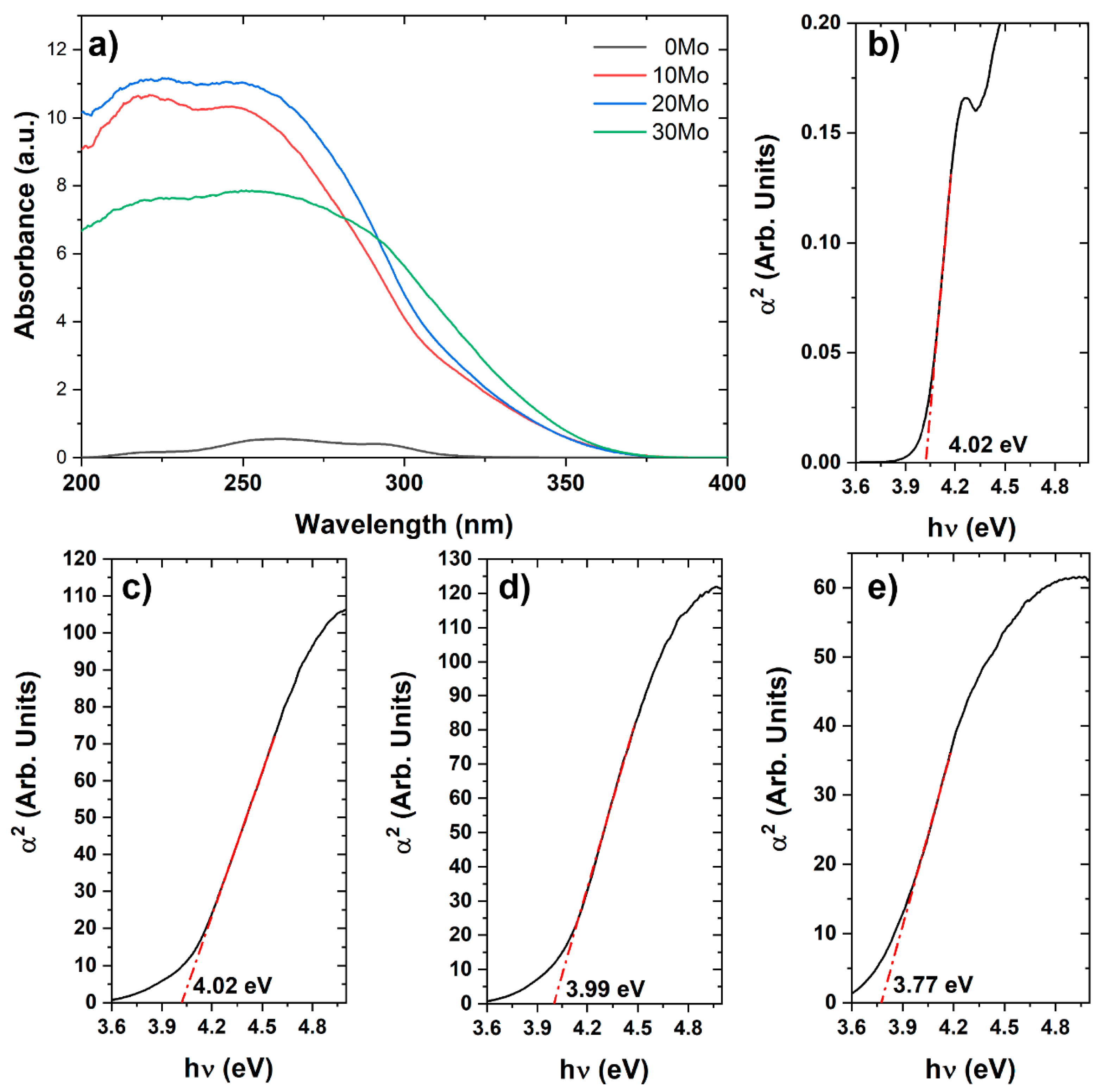

Spectroscopic analysis in the ultraviolet-visible region was performed using diffuse reflectance, and the data were converted to absorption based on the theory proposed by Kubelka and Munk [

16], as shown in

Figure 3a. The effect of this extended absorption range on the band gap energy (Egap) of the materials was analyzed using the methodology proposed by Wood and Tauc [

17], based on the direct transition, which is presented below in Equation 1:

where h is the Planck constant, ν is the photon’s frequency, Eg is the band gap energy, and B is a constant. The γ factor depends on the nature of the electron transition and is equal to 1/2 or 2 for the direct and indirect transition band gaps, respectively. Thus, aiming at the analysis using the direct transition, in this work γ = 1/2 was used.

As observed, the pure CdWO

4 sample exhibits low absorption compared to the heterostructures, with its maximum absorption bands around 261 and 292 nm. On the other hand, the formation of heterostructures not only increases the intensity but also extends the absorption spectrum to longer wavelengths. However, it is noted that even the heterostructures still exhibit absorption in the ultraviolet region. According to

Figure 3b–e, a decrease in Egap is observed as the amount of CdMoO

4 in the heterostructure increases, reducing from 4.02 eV to 3.77 eV, from the 0Mo sample to the 30Mo sample. The formation of a heterojunction with two or more distinct phases can induce the emergence of new intermediate electronic states within the bands of the compound, facilitating electronic transitions and consequently reducing the band gap (Egap) of the heterostructure [

21].

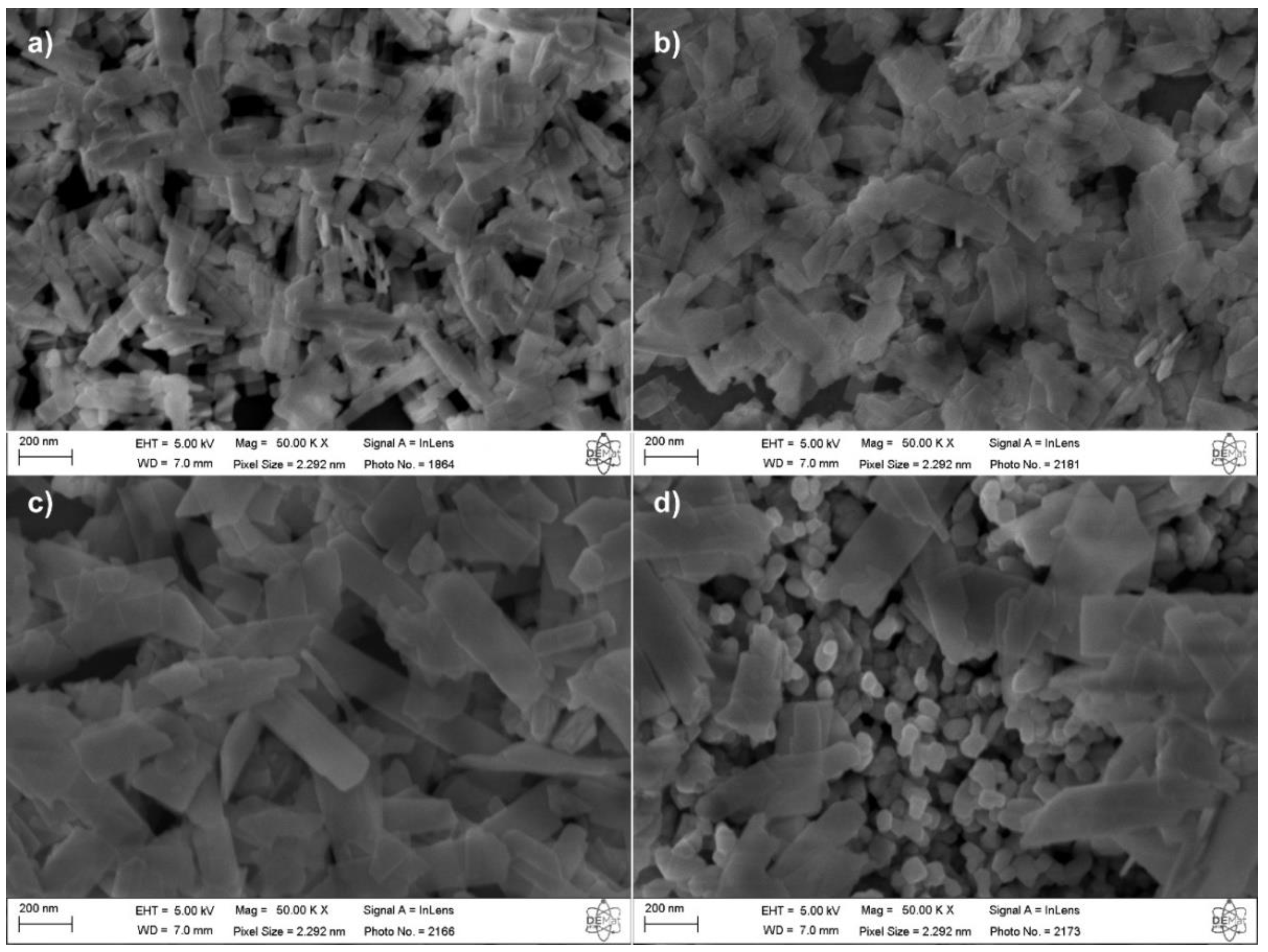

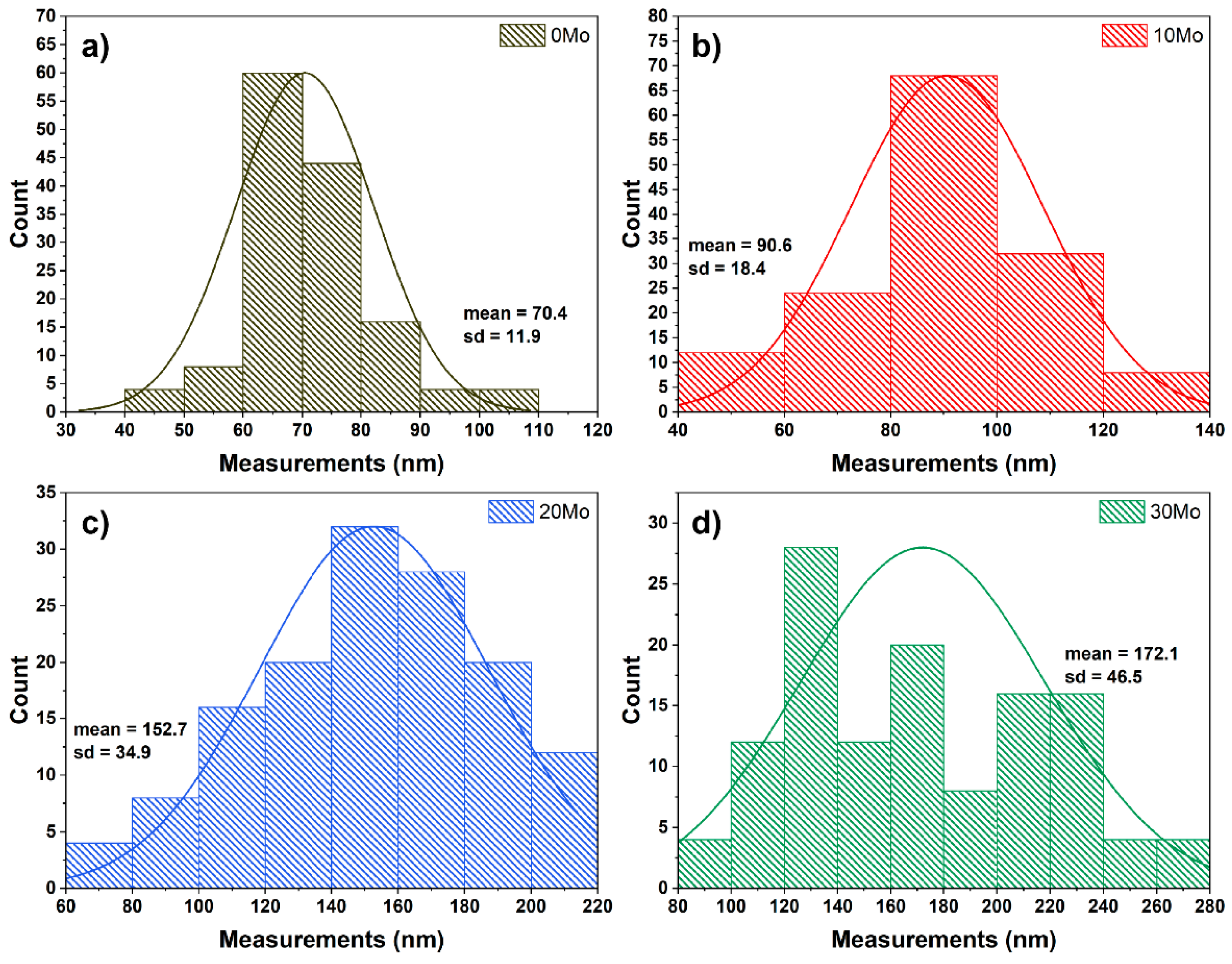

The CdWO

4 samples and heterostructures were morphologically characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and the obtained micrographs are presented in

Figure 4. The micrograph of the 0Mo sample reveals that the CdWO

4 phase exhibits a plate-like morphology with a rectangular appearance, where the plate length shows some variation. The micrographs of the other samples (

Figure 4b–d) indicate that as the amount of CdMoO

4 increases in the synthesis, the CdWO

4 plates become wider. This morphological change in the CdWO

4 phase is further confirmed in

Figure 5, which presents the width distribution histogram of these plates. The measurements were performed using the ImageJ software, considering at least 120 measurements from images acquired at different scales for quantification. It is worth noting that the plate morphology is characterized by two well-defined dimensions: the longer one, referred to as the length, and the shorter one, referred to as the width. As observed in

Figure 5, the average plate width increases from 70.4 nm in the 0Mo sample to 172.1 nm in the 30Mo sample. Additionally, an increase in standard deviation is also observed, indicating greater size variation as the CdMoO

4 content increases in the synthesis.

Figure 4d further highlights the presence of CdMoO

4 particles, which exhibit an irregular spherical morphology. In the 10Mo and 20Mo samples, similar particles can also be observed, albeit more sparsely distributed among the CdWO

4 plates. The average size of the CdMoO

4 nanoparticles was estimated by measuring diameters in two perpendicular directions. The results indicate that the CdMoO

4 nanoparticles have an average diameter of 68.3 nm with a standard deviation of 12.3 nm.

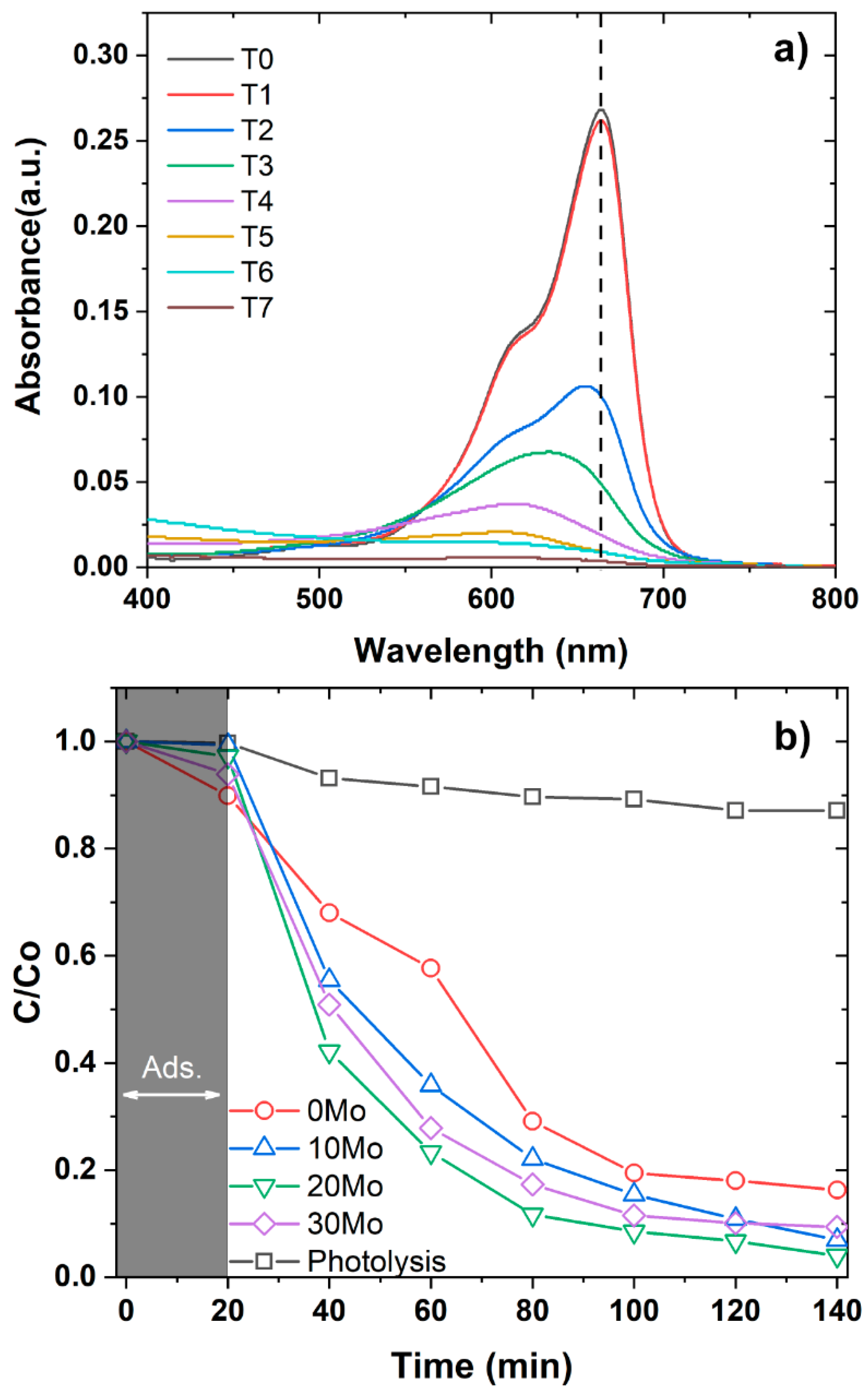

The photocatalytic properties of CdWO

4 and your heterostructures were evaluated using methylene blue (MB) as the target dye. For this purpose, absorbance curves (

Figure 6a) were analyzed for aliquots collected at 20 min intervals. Initially, an aliquot of the dye solution was collected before contact with the samples, referred to as C

0. Subsequent aliquots were labeled as C, and the concentration variation curves (C/C

0) were plotted, as shown in

Figure 6b. The analysis of the C/C

0 curves confirms that all tested samples exhibit photocatalytic activity, accelerating the degradation of the dye under light irradiation. This effect is particularly evident when comparing the concentration variation of the samples to photolysis alone. Additionally,

Figure 6b indicates that the 0Mo sample exhibits the highest adsorption capacity among all studied samples. This result is consistent with FESEM images, which revealed that this sample has the smallest particle size, leading to a larger contact area with the surrounding medium. On the other hand, despite its high adsorption capacity, the 0Mo sample demonstrated the lowest photocatalytic activity. The three heterostructures studied exhibited similar photocatalytic efficiency, with the 20Mo sample achieving the best performance by degrading 96% of the MB dye after 2 h of testing. The 10Mo and 30Mo samples followed, degrading 94% and 92% of the dye, respectively.

The evaluation of the photocatalytic efficiency of semiconductor materials can be more accurately assessed based on kinetic constants. In this context, photocatalytic processes in semiconductor materials are typically modeled using a first-order kinetic constant, as described by the equation presented in Equation 2 [

22]:

where C is absorbance of methylene blue at time t; C

0 is initial absorbance; t is irradiation time; k is kinetic constant.

The kinetic constants calculated using Equation 02 are presented in

Table 1. As observed, the 20Mo sample exhibits the highest kinetic constant, indicating the fastest reaction rate. The R

2 values demonstrate good reliability of the results, confirming that the first-order kinetic model provides a good fit to the experimental data. This model is applicable in processes where pollutant adsorption onto the samples is low and the radiation intensity remains constant, ensuring that photocatalysis proceeds in an approximately linear manner [

23].

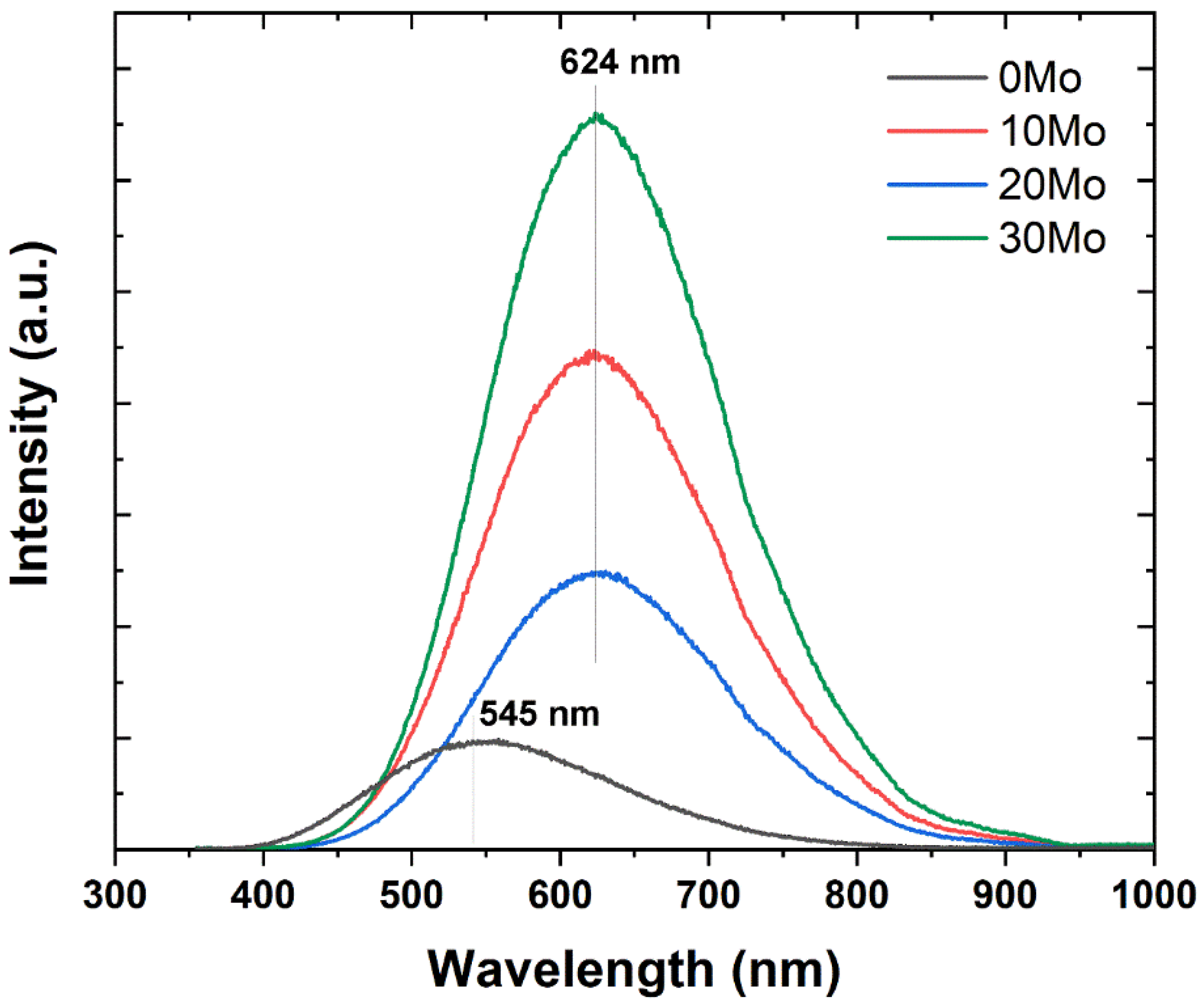

To gain further insights into charge carrier dynamics in the synthesized samples, photoluminescence (PL) measurements were performed.

Figure 7 presents the PL spectra obtained under 335 nm laser excitation. As shown in

Figure 7, the CdWO

4 sample exhibits the lowest photoluminescence intensity, with an emission band centered around 545 nm. In contrast, the heterostructures display higher photoluminescence intensity compared to the pure phase, along with a redshift of the emission band to 624 nm. This shift is attributed to the simultaneous presence of CdWO

4 and CdMoO

4 phases and an increase in intrinsic defects, such as oxygen vacancies, which promote emission towards the red region [

24]. The enhanced photoluminescence intensity observed in the heterostructures compared to the pure sample suggests a Type-I heterostructure, where electrons (e

-) and holes (h

+) accumulate in the same region of the material, facilitating e

-/h

+ recombination [

25]. Additionally, an increase in CdMoO

4 content within the heterostructure correlates with higher PL intensity, indicating a greater number of e

-/h

+ recombination events. These findings align with the photocatalytic results, where the 20Mo sample demonstrated the highest degradation efficiency for methylene blue.