Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

| Reagent Name | Chemical formula | Purity | CAS No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate | Bi(NO3)3 x 5H2O | ≥99% (AR) | 10035-06-0 |

| Ammonium metavanadate | NH4VO3 | 99 % | 7803-55-6 |

| Nitric acid | HNO3 | ≥99% (AR) | 7697-37-2 |

| Acid Orange 7(AO7) | C₁₆H₁₁N₂NaO₄S | 95% (dye grade) | 633-96-5 |

2.2. Synthesis of BiVO4

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Photocatalytic Activity Evaluation

2.5. Antibacterial Properties

3. Results and Discussion

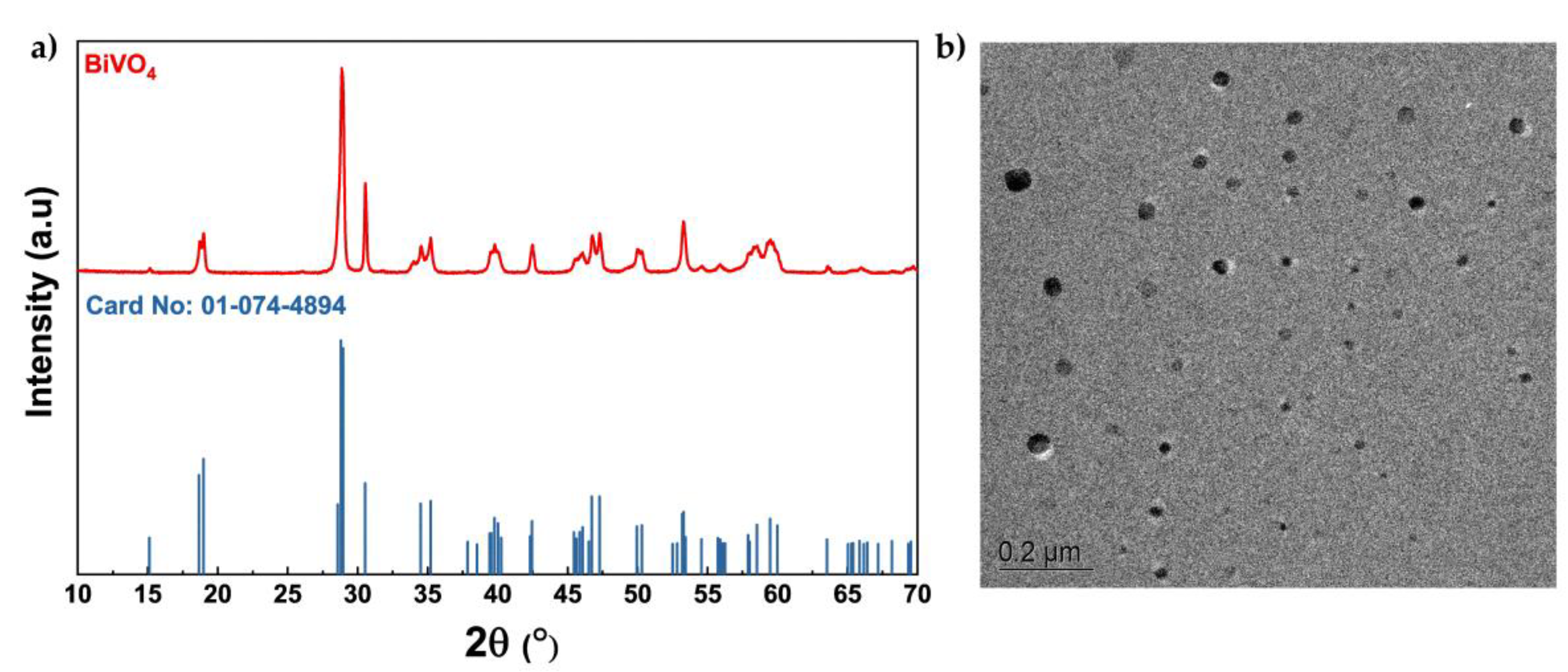

3.1. Structural and Morphological Properties of the Microwave-Synthesized BiVO4

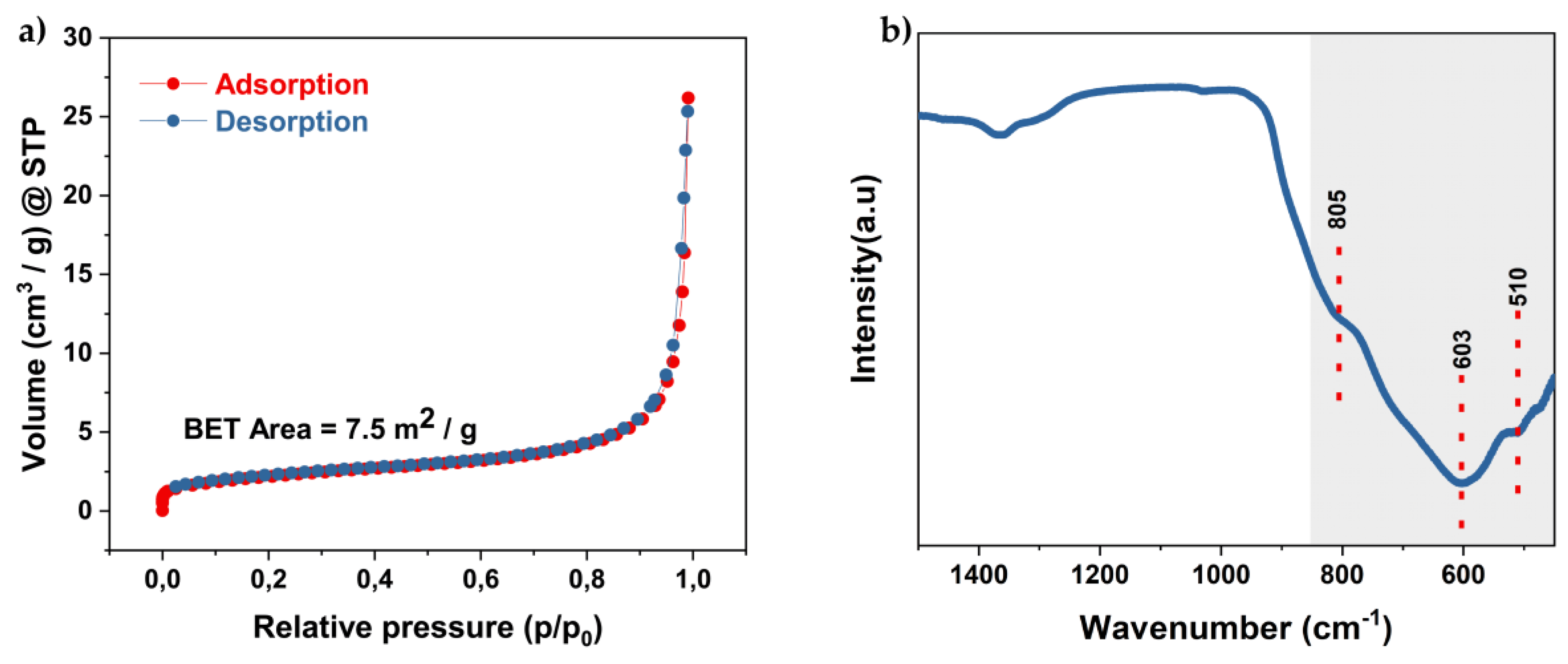

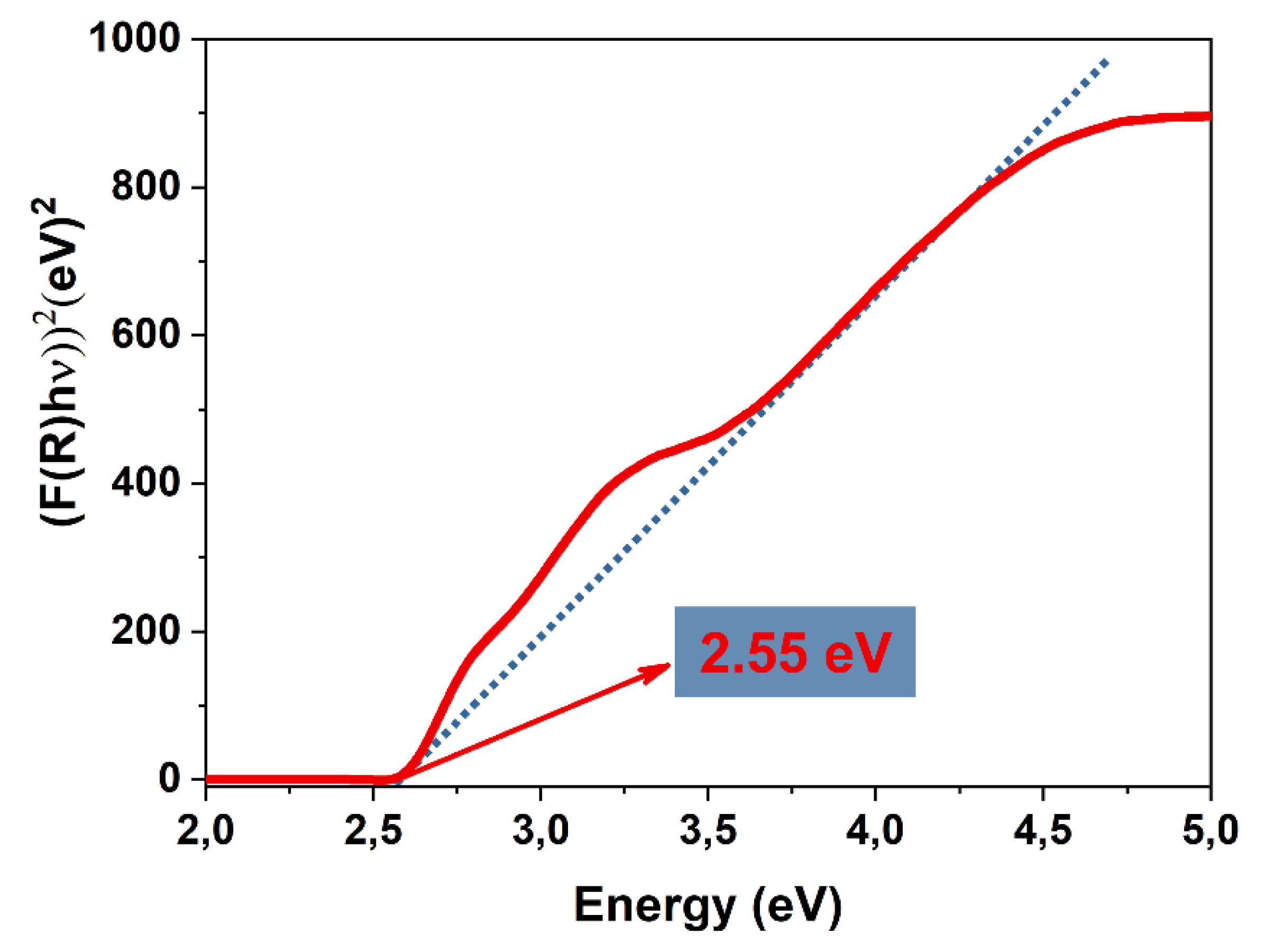

3.2. Textural, Vibrational, and Optical Properties of the Microwave-Synthesized BiVO₄

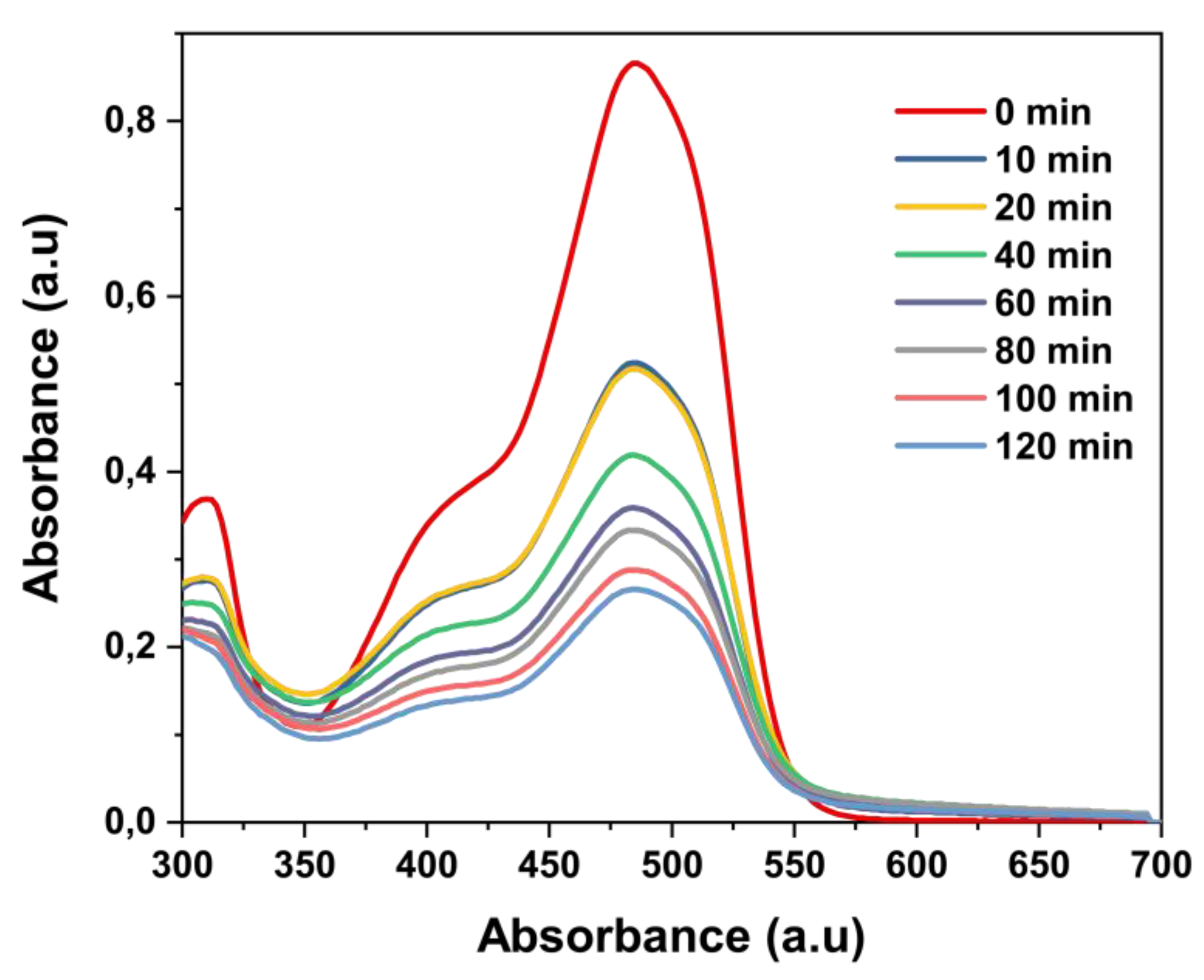

3.3. Photocatalytic Performance of the Microwave-Synthesized BiVO₄

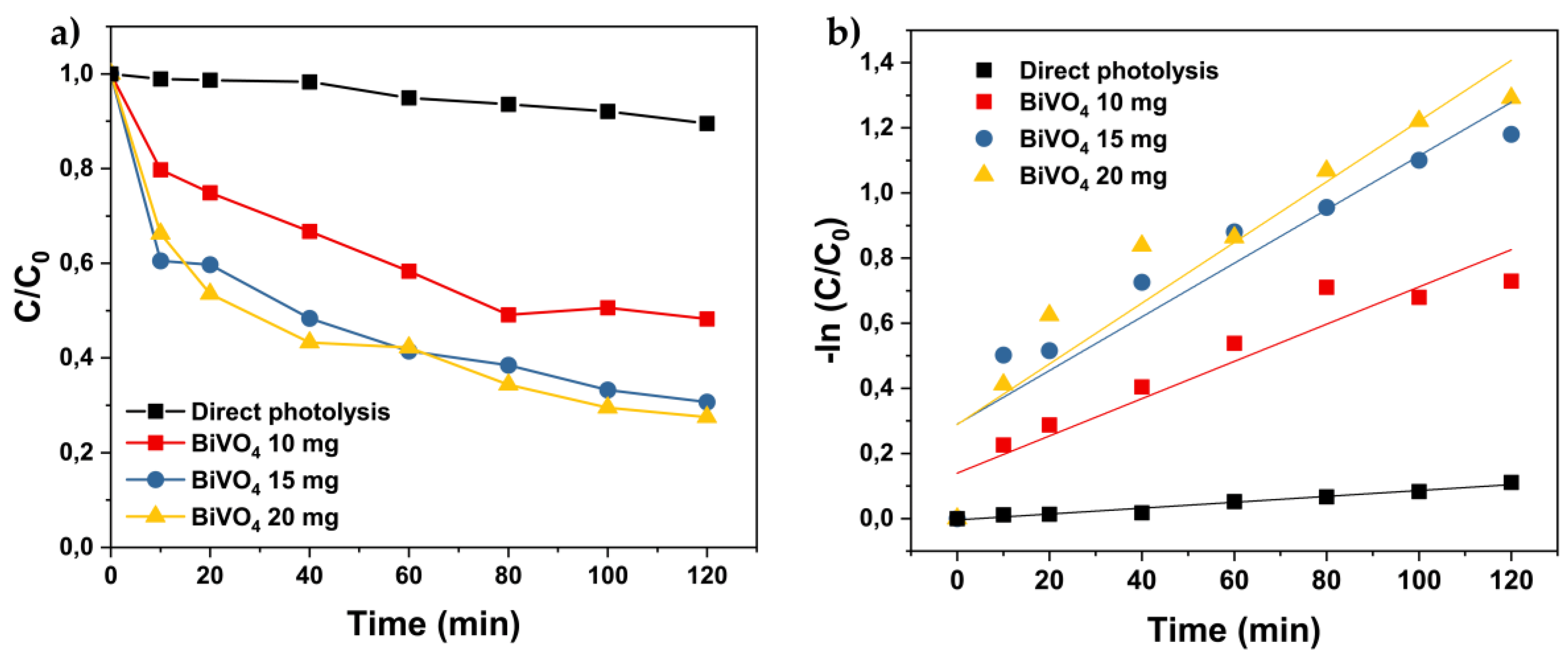

3.3.1. The Effect of Catalyst Dosage on the Degradation of Acid Orange 7

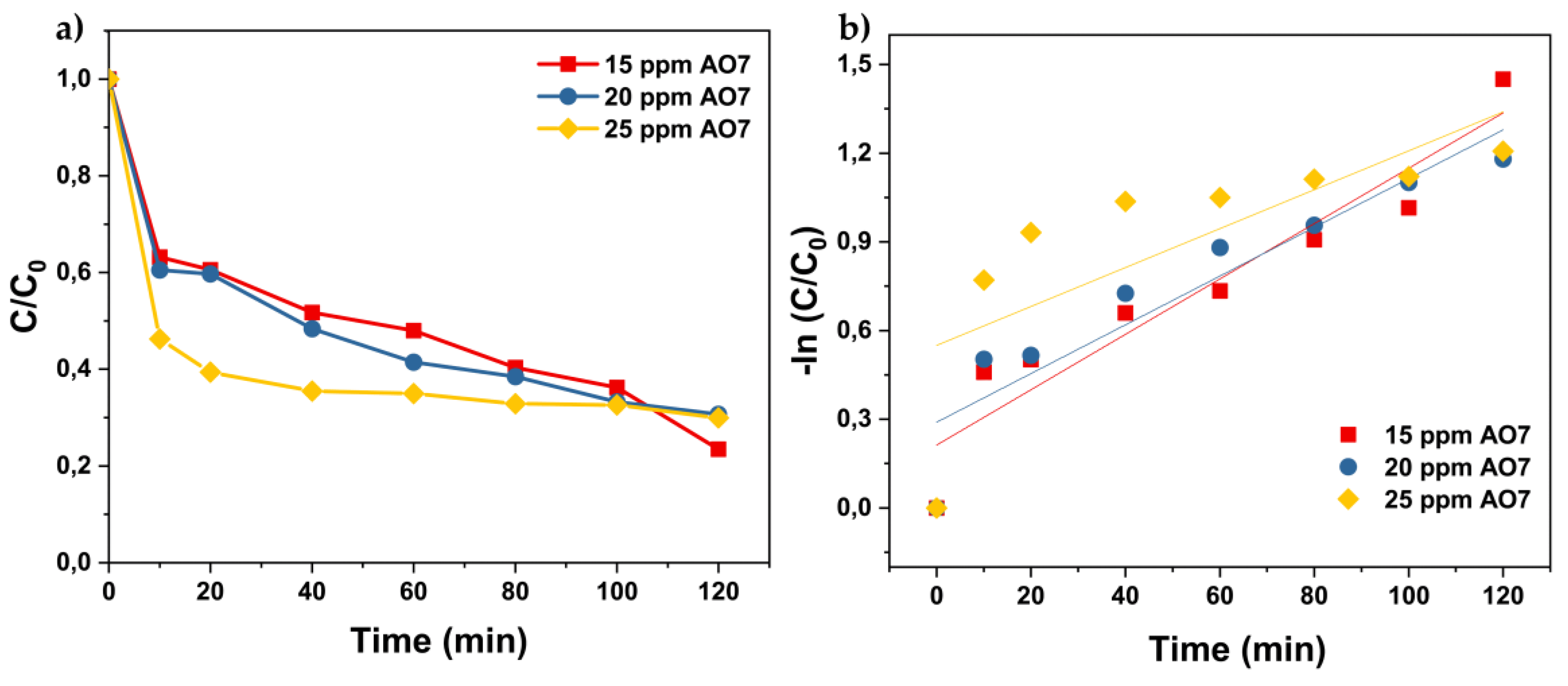

3.3.2. Effect of the Initial Concentration of Pollutant Acid Orange 7 on Photocatalytic Degradation Efficiency

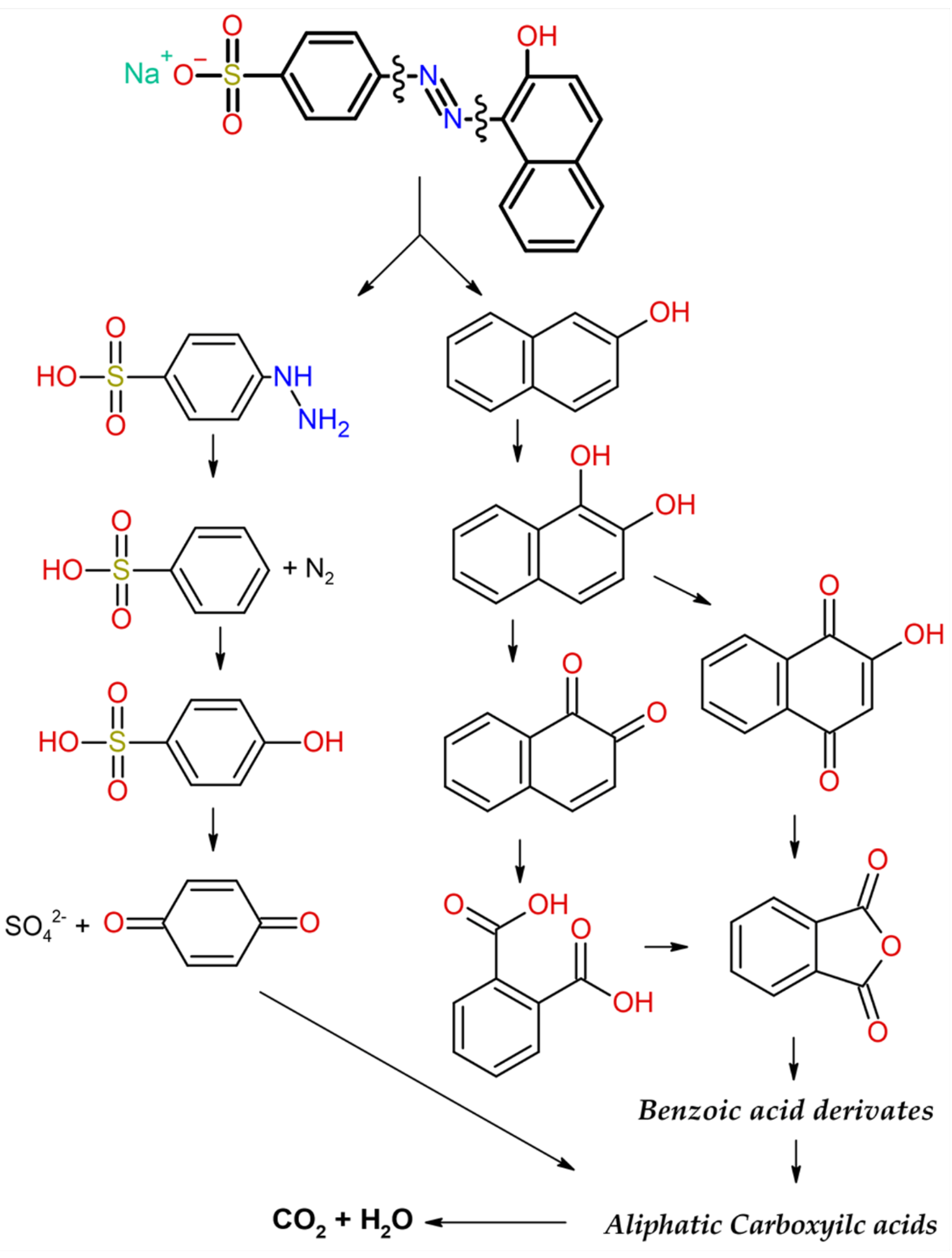

3.4. Possible Photocatalytic Pathway for the Degradation of Acid Orange 7

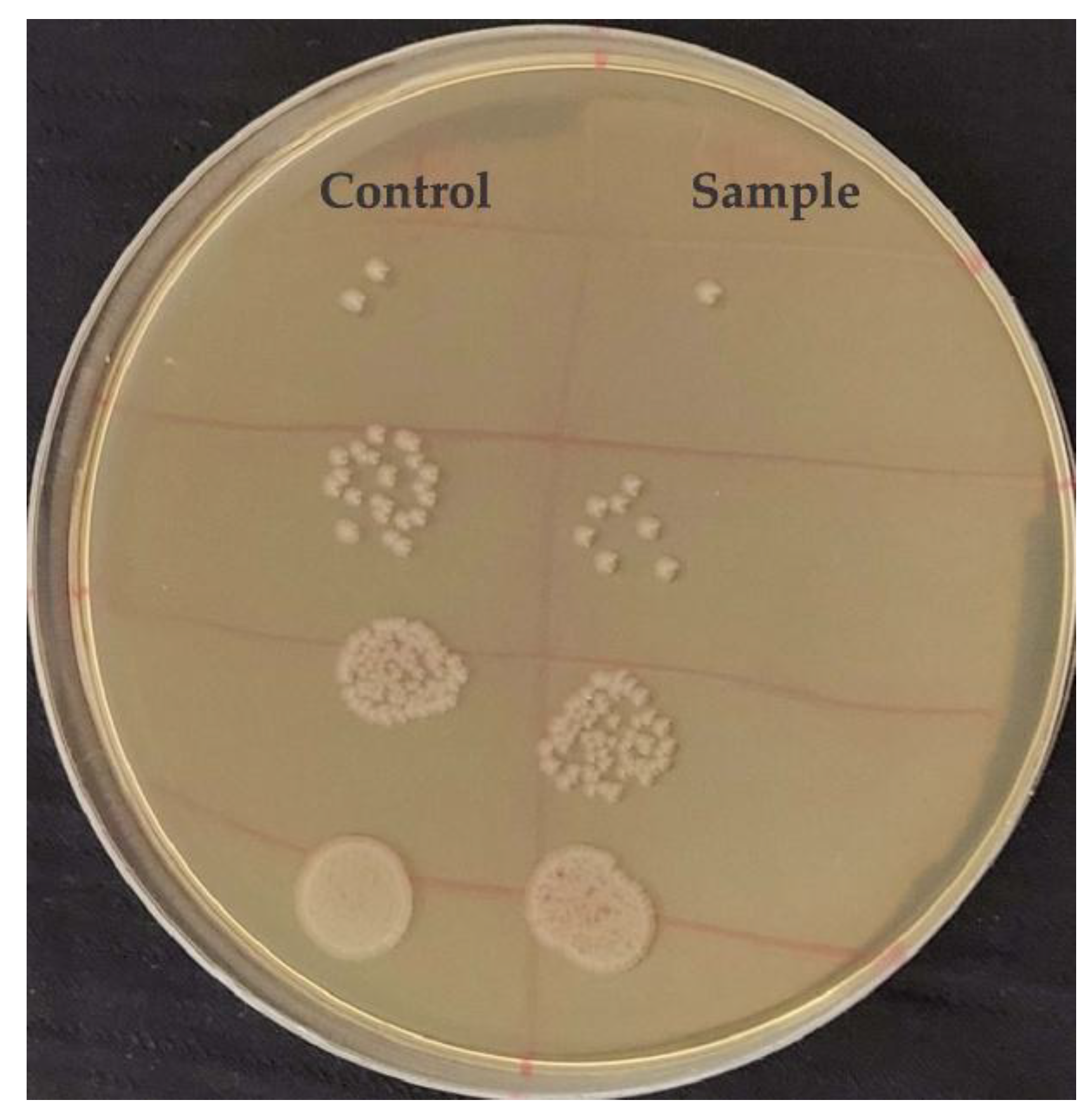

3.4. Antibacterial Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moghimi Dehkordi, M.; Pournuroz Nodeh, Z.; Soleimani Dehkordi, K.; Salmanvandi, H.; Rasouli Khorjestan, R.; Ghaffarzadeh, M. Soil, Air, and Water Pollution from Mining and Industrial Activities: Sources of Pollution, Environmental Impacts, and Prevention and Control Methods. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.S.; Deepthi, D.; Harshitha, S.; Sonkusare, S.; Naik, P.B.; Kumari, N.S.; Madhyastha, H. Environmental Pollutants and Their Effects on Human Health. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Mitrowska, K.; Posyniak, A. Synthetic Organic Dyes as Contaminants of the Aquatic Environment and Their Implications for Ecosystems: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, H.B.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Pourhassan, Z.; Alenezi, F.N.; Silini, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Oszako, T.; Luptakova, L.; Golińska, P.; Belbahri, L. Diversity of Synthetic Dyes from Textile Industries, Discharge Impacts and Treatment Methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaya, S.; M’rabet, S.; El Harfi, A. Classifications, Properties, Recent Synthesis and Applications of Azo Dyes. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumlata, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ambade, B.; Kumar, A.; Gautam, S. Sustainable Solutions: Reviewing the Future of Textile Dye Contaminant Removal with Emerging Biological Treatments. Limnol. Rev. 2024, 24, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Roy, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Banerjee, D.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. Contamination of Textile Dyes in Aquatic Environment: Adverse Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystem and Human Health, and Its Management Using Bioremediation. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 353, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, N.; Aber, S.; Hosseinzadeh, F. Study of C.I. Acid Orange 7 Removal in Contaminated Water by Photo Oxidation Processes. Glob. NEST J. 2008, 10, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathi, S.; El Din Mahmoud, A. Trends in Effective Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervolino, G.; Vaiano, V.; Pepe, G.; Campiglia, P.; Palma, V. Degradation of Acid Orange 7 Azo Dye in Aqueous Solution by a Catalytic-Assisted, Non-Thermal Plasma Process. Catalysts 2020, 10, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanos, F.; Razzouk, A.; Lesage, G.; Cretin, M.; Bechelany, M. A Comprehensive Review on Modification of Titanium Dioxide-Based Catalysts in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.-C.; Kim, K.-S. Effect of TiO2 Thin Film Thickness on NO and SO2 Removals by Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Photocatalyst Hybrid Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 5296–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, C.; Ren, Z.; Yang, X. Single Molecule Photocatalysis on TiO2 Surfaces: Focus Review. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 11020–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etacheri, V.; Di Valentin, C.; Schneider, J.; Bahnemann, D.; Pillai, S.C. Visible-Light Activation of TiO2 Photocatalysts: Advances in Theory and Experiments. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2015, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiba, A.; Alansi, A.M.; Oubelkacem, A.; Chabri, I.; Hameed, S.T.; Afzal, N.; Rafique, M.; Qahtan, T.F. Sunlight-Driven Synthesis of TiO2/(MA)2SnCl4 Nanocomposite Films for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Catalysts 2025, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigaki, T.; Nakada, Y.; Tarutani, N.; Uchikoshi, T.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Isobe, M.; Ogata, H.; Zhang, C.; Hao, D. Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Anatase-Rutile Mixed-Phase Nano-Size Powder Given by High-Temperature Heat Treatment. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamble, G.S.; Natarajan, T.S.; Patil, S.S.; Thomas, M.; Chougale, R.K.; Sanadi, P.D.; Siddharth, U.S.; Ling, Y.-C. BiVO4 As a Sustainable and Emerging Photocatalyst: Synthesis Methodologies, Engineering Properties, and Its Volatile Organic Compounds Degradation Efficiency. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolić, S.D.; Jovanović, D.J.; Štrbac, D.; Far, L.Đ.; Dramićanin, M.D. Improved Coloristic Properties and High NIR Reflectance of Environment-Friendly Yellow Pigments Based on Bismuth Vanadate. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 22731–22737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolić, S.D.; Jovanović, D.J.; Smits, K.; Babić, B.; Marinović-Cincović, M.; Porobić, S.; Dramićanin, M.D. A Comparative Study of Photocatalytically Active Nanocrystalline Tetragonal Zyrcon-Type and Monoclinic Scheelite-Type Bismuth Vanadate. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 17953–17961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Choi, K.S.; Shin, H.-M.; Kim, T.L.; Song, J.; Yoon, S.; Jang, H.W.; Yoon, M.-H.; Jeon, C.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, S. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance Depending on Morphology of Bismuth Vanadate Thin Film Synthesized by Pulsed Laser Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić, S.T.; Ćirković, J.; Jovanović, J.; Novaković, T.; Podlogar, M.; Mitrić, J.; Branković, G.; Branković, Z. High Efficiency Solar Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Mordant Blue 9 by Monoclinic BiVO4 Nanopowder. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 333, 130341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, C.; Dhakal, D.; Lee, S.W. Visible-Light-Induced Ag/BiVO4 Semiconductor with Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Performance. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 064001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, J. Effects of Europium Doping on the Photocatalytic Behavior of BiVO4. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisya, K.T.; Solís-López, M.; Ríos-Ramírez, J.J.; Durán-Álvarez, J.C.; Rousseau, A.; Velumani, S.; Asomoza, R.; Kassiba, A.; Jantrania, A.; Castaneda, H. Electronic and Optical Competence of TiO2/BiVO4 Nanocomposites in the Photocatalytic Processes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.-H.; Fei, X.; Ni, L.; Telegin, F. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Acid Orange 7 by AgBr/BiVO4 under Visible Light. J. Fiber Bioeng. Inform. 2018, 11, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, D.T. Exploring the Dual Role of BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Unveiling Enhanced Antimicrobial Efficacy and Photocatalytic Performance. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 114, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramila, S.; Nagaraju, G.; Mallikarjunaswamy, C.; Latha, K.C.; Chandan, S.; Ramu, R.; Rashmi, V.; Lakshmi Ranganatha, V. Green Synthesis of BiVO4 Nanoparticles by Microwave Method Using Aegle marmelos Juice as a Fuel: Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Study. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2020, 10, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, D.; Righini, G.C.; Ferrari, M. Advances in Synthesis and Applications of Bismuth Vanadate-Based Structures. Inorganics 2025, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, D.; Righini, G.C.; Ferrari, M. Synthesis, Optical, and Photocatalytic Properties of the BiVO4 Semiconductor Nanoparticles with Tetragonal Zircon-Type Structure. Photonics 2025, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, X.; Qu, J.; Xiong, F.; Xuan, H.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, H. Visible-Light-Driven Antimicrobial Activity and Mechanism of Polydopamine-Reduced Graphene Oxide/BiVO4 Composite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-J.; Yu, H.-Q.; Li, Q.-R. Radiolytic Degradation of Acid Orange 7: A Mechanistic Study. Chemosphere 2005, 61, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Huang, X.; Mohamedali Hamid, K.; Yuan, H.; Batool, I.; Yang, Y. Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysis of BiVO4@Diatomite for Degradation of Methoxychlor. Catalysts 2025, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, M.A.; Zheng, A.L.T.; Tan, H.Y.; Sarbini, S.R.; Tan, K.B.; Boonyuen, S.; Wong, K.K.S.; Chung, E.L.T.; Lease, J.; Andou, Y. Assessing the Photocatalytic Performance of Hydrothermally Synthesized Fe-Doped BiVO4 Under Low-Intensity UV Irradiation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.J.; Lopes, A.; Pacheco, M.J.; Ciríaco, L. Visible-Light-Driven AO7 Photocatalytic Degradation and Toxicity Removal at Bi-Doped SrTiO3. Materials 2022, 15, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, K.M.; Kurny, A.; Gulshan, F. Parameters Affecting the Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Using TiO2: A Review. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenjo, N.G.; Santamaría, R.; Blanco, C.; Granda, M.; Álvarez, P.; Menéndez, R. Correct Use of the Langmuir–Hinshelwood Equation for Proving the Absence of a Synergy Effect in the Photocatalytic Degradation of Phenol on a Suspended Mixture of Titania and Activated Carbon. Carbon 2013, 55, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanichphant, S.; Nakaruk, A.; Chansaenpak, K.; Channei, D. Evaluating the Photocatalytic Efficiency of the BiVO4/rGO Photocatalyst. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, B. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes: An Overview. Curr. Catal. 2018, 7, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).