1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent malignancy worldwide, affecting millions of women annually [

1]. Despite advancements in treatment modalities that have contributed to improved survival rates, a significant postoperative concern persists regarding the potential for breast deformity, which can profoundly affect patients both physically and psychologically. Consequently, in recent decades, there has been a discernible shift towards favoring breast-conserving surgery (BCS) over mastectomy with the aim of preserving as much healthy breast skin as possible [

2,

3]. However, it is important to note that BCS may result in varying degrees of asymmetry, volume loss, and alterations in breast shape.

Traditionally, fat grafting has been the primary choice for reconstructive methods aimed at revising postoperative breast deformities by restoring volume and improving symmetry [

4]. However, the effectiveness and durability of fat grafting can vary because of the resorption rates of grafted fat, which are influenced by multiple factors including patient age, donor site of the fat tissues, graft technique, and irradiation of the recipient site, leading to unpredictable long-term outcomes [

5]. Additionally, the availability of sufficient donor fat tissues may be limited in lean patients.

As the incidence of breast cancer increases, there is a continuous unmet need for innovative solutions that can reliably and effectively address breast deformities following BCS while minimizing donor-site morbidity through autologous tissue reconstruction and achieving long-lasting results. An innovative approach involves the development of absorbable scaffolds tailored specifically for breast tissue regeneration. Absorbable scaffolds represent a unique strategy for breast reconstruction by providing a temporary structural framework that supports tissue ingrowth and remodeling. These scaffolds can be engineered to mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) of the breast tissue, thereby promoting cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Additionally, they offer the advantage of gradual degradation over time, leaving behind regenerated tissues that seamlessly integrate with the surrounding tissues.

From the perspective of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, absorbable scaffolds have the potential to revolutionize the field of breast reconstruction following malignancy treatment. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the biocompatibility and efficacy of optimized three-dimensional (3D) micro-nanofiber scaffolds (H&BIO Co., Ltd., Seongnam, Korea). Furthermore, we aimed to demonstrate the clinical potential of these scaffolds through preclinical experiments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

Seven-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Seoul, Korea) were randomly divided into four groups. Group I, the control group, received a 2-dimensional (2D) micro-nanofiber scaffold weighing 0.2 g, while Groups II to IV received 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds (H&BIO Co., Ltd.) weighing 0.2 g, 0.3 g, and 0.6 g, respectively (Table 1). The scaffolds were subcutaneously implanted on the backs of the rats and harvested with surrounding tissues 4, 8, and 16 weeks after implantation.

2.2. Animal Model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 260–300 g were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. The rats were acclimated to their environment for a minimum of 1 week prior to use. All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University Hospital (IACUC 22-0190-S1A0(2)). Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering, reduce the number of animals used, and employ alternatives to in vivo techniques whenever available.

2.3. Histological Analyses

The scaffolds and surrounding tissues were extracted and treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, followed by embedding in paraffin. Subsequently, tissues were sectioned into 5-µm-thick slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general histological evaluation and Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining to assess collagen deposition [

6]. H&E-stained slides were analyzed under a light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to evaluate the pathological changes, including cellular infiltration and inflammatory responses. MT-stained slides were used to visualize collagen distribution, where collagen fibers appeared blue, the cytoplasm and muscle fibers appeared red, and the nuclei appeared black. Histological images were captured using a Leica SCN400 Image Viewer 12.3.3 (Leica Biosystems Imaging, Inc., Nussloch GmbH, Germany), and quantitative assessments of cell infiltration and collagen deposition were performed using computerized planimetry. Histological evaluation of the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds was conducted following the ISO standards (ISO 10993-6:2016) with inflammatory cell types, including polymorphonuclear cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, giant cells, and necrotic regions, systematically assessed.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All values are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Given the small sample size and non-normal distribution of the data, Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric tests were employed to compare differences between independent groups. One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were categorized based on their p-values and are denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Cell Infiltration into Scaffolds

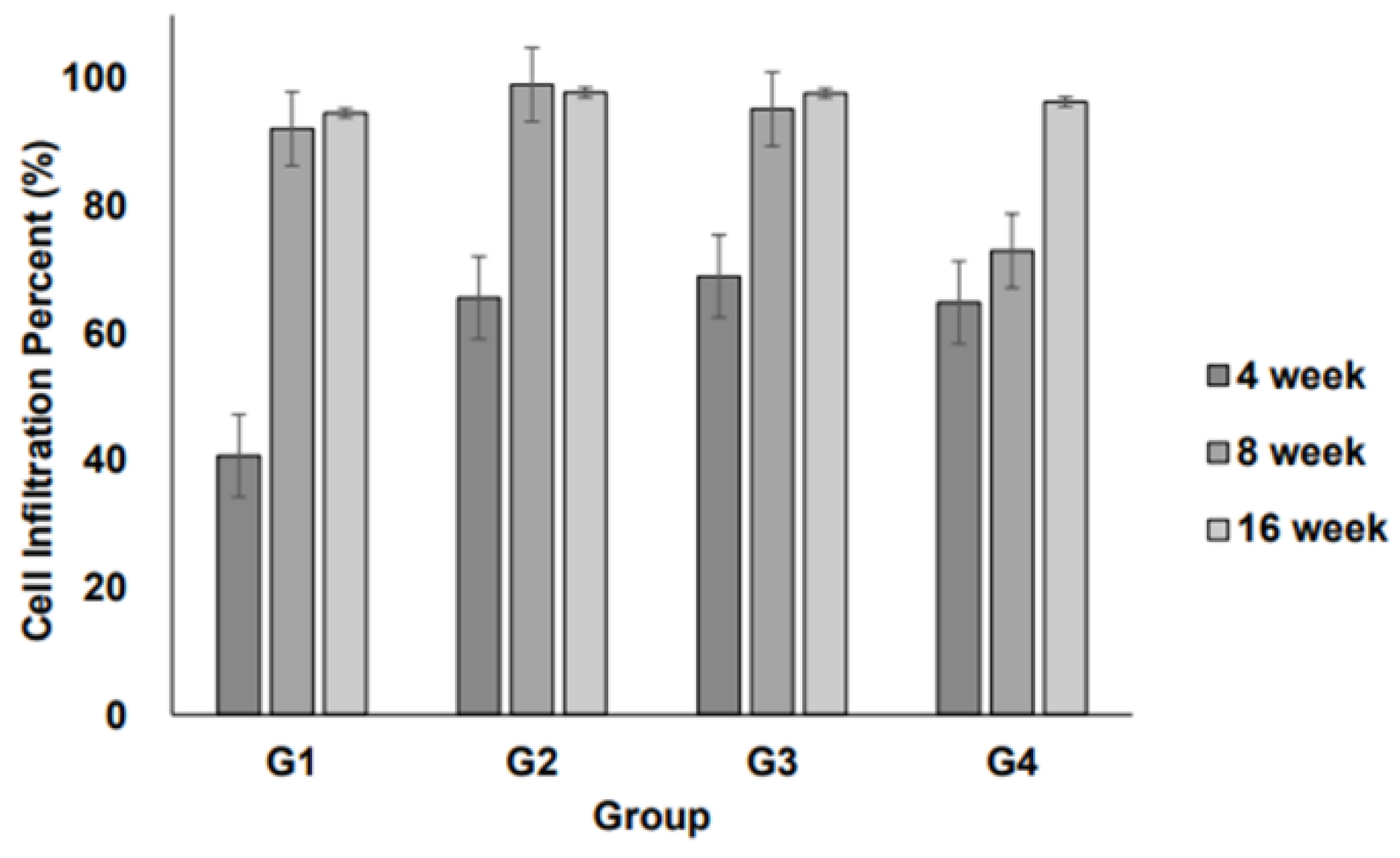

Cell infiltration into the implanted scaffolds was assessed over time (4, 8, and 16 weeks) for each group. The degree of cellular infiltration progressively increased in all groups over time, indicating that the host cells actively migrated into the scaffold structures (

Figure 1).

At 4 weeks, Group I (2D scaffold) exhibited the lowest level of cell infiltration, whereas Groups II–IV (3D scaffolds) showed significantly higher levels. Infiltration was comparable among the 3D scaffold groups. After 8 weeks, a notable increase in cellular infiltration was observed across all groups. The 3D scaffold groups maintained a higher degree of infiltration than the 2D scaffold group, suggesting that the 3D structures facilitated better cell migration and integration with host tissues. At 16 weeks, cellular infiltration continued to progress and reached peak levels. The 3D scaffold groups showed a well-integrated cellular presence within the scaffold structures, with no substantial differences between Groups II, III, and IV. Meanwhile, although Group I (2D scaffold) exhibited increased infiltration compared to earlier time points, it remained lower than that of the 3D scaffold groups.

However, among the different 3D scaffold weights (0.2 g, 0.3 g, and 0.6 g), no significant differences were observed in infiltration levels, suggesting that increasing scaffold weight within this range does not substantially impact cellular infiltration.

3.2. Inflammation at the Interface of Scaffolds

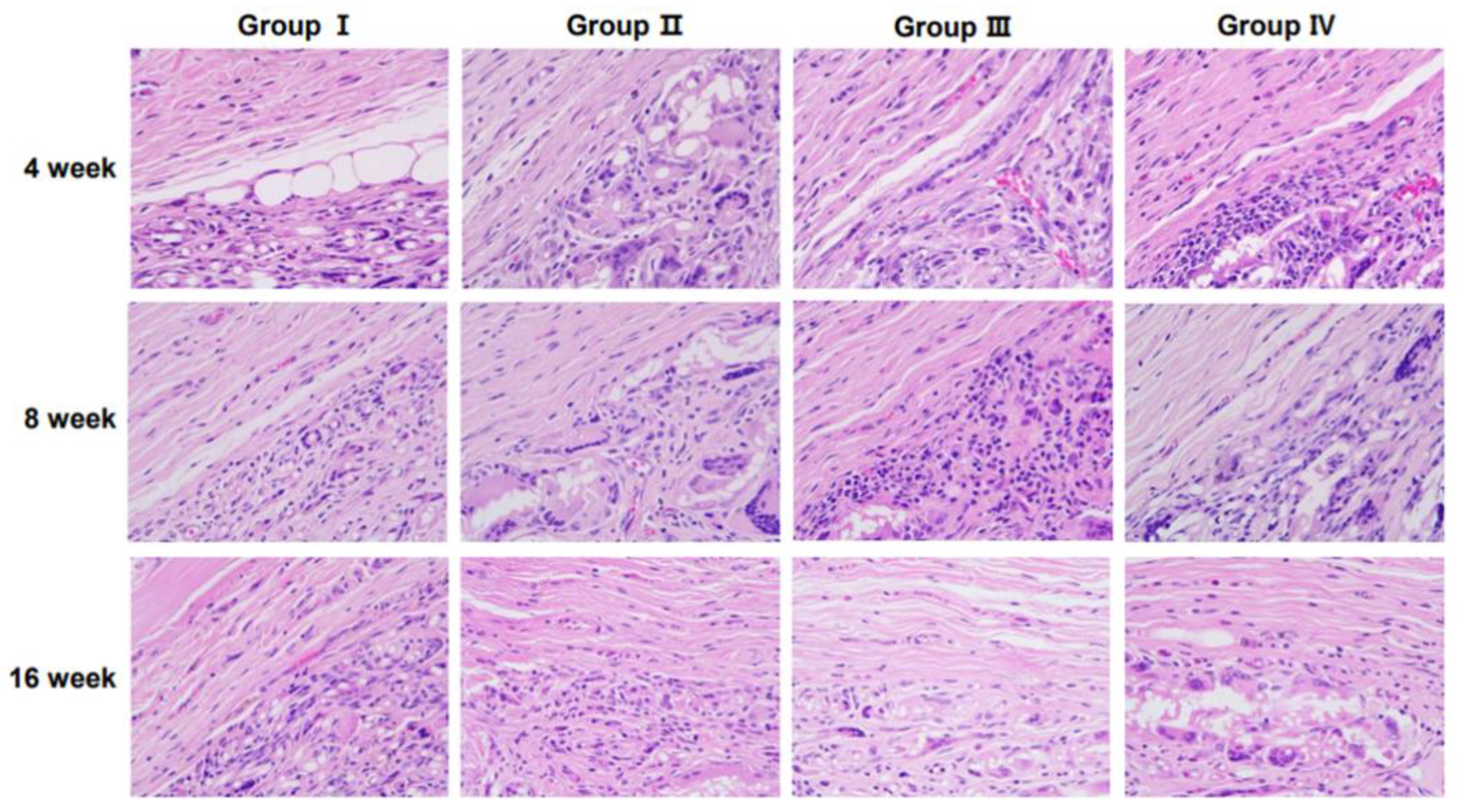

Representative histological images of H&E-stained sections demonstrating tissue responses are shown in

Figure 2. The number of inflammatory cells varied among groups over time, with notable differences observed at specific time points.

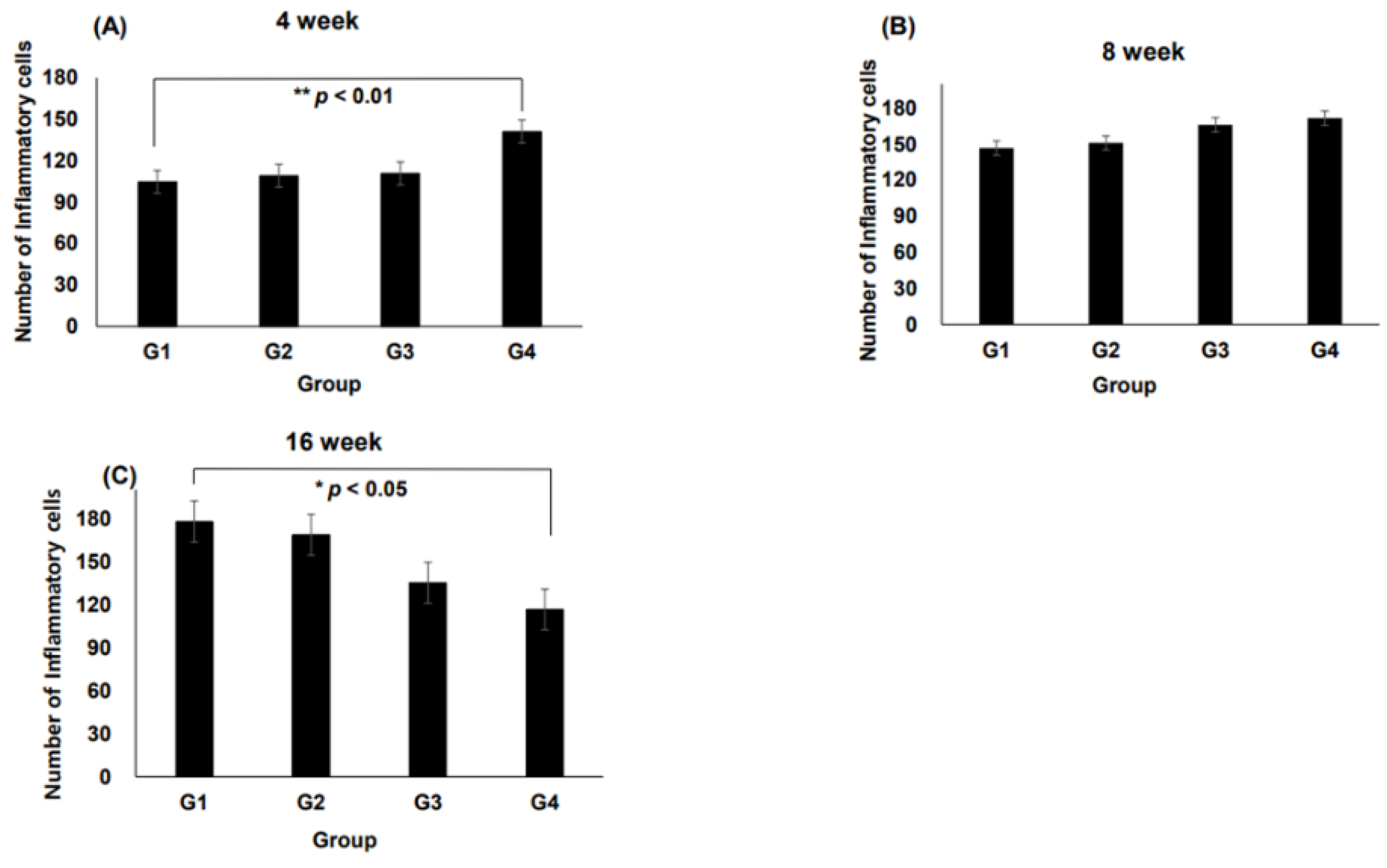

At 4 weeks, Group IV exhibited a significantly higher number of inflammatory cells than Groups II and III, with a statistically significant increase observed compared with Group I (

p < 0.01,

Figure 3A). After 8 weeks, inflammatory cell infiltration remained prominent across all groups. Notably, Group III showed an increase in inflammatory cells compared with Group I (

Figure 3B). At 16 weeks, a significant reduction in the inflammatory cell count was observed in Group IV compared with that in Group I (

p < 0.05,

Figure 3C), indicating a potential resolution of inflammation over time.

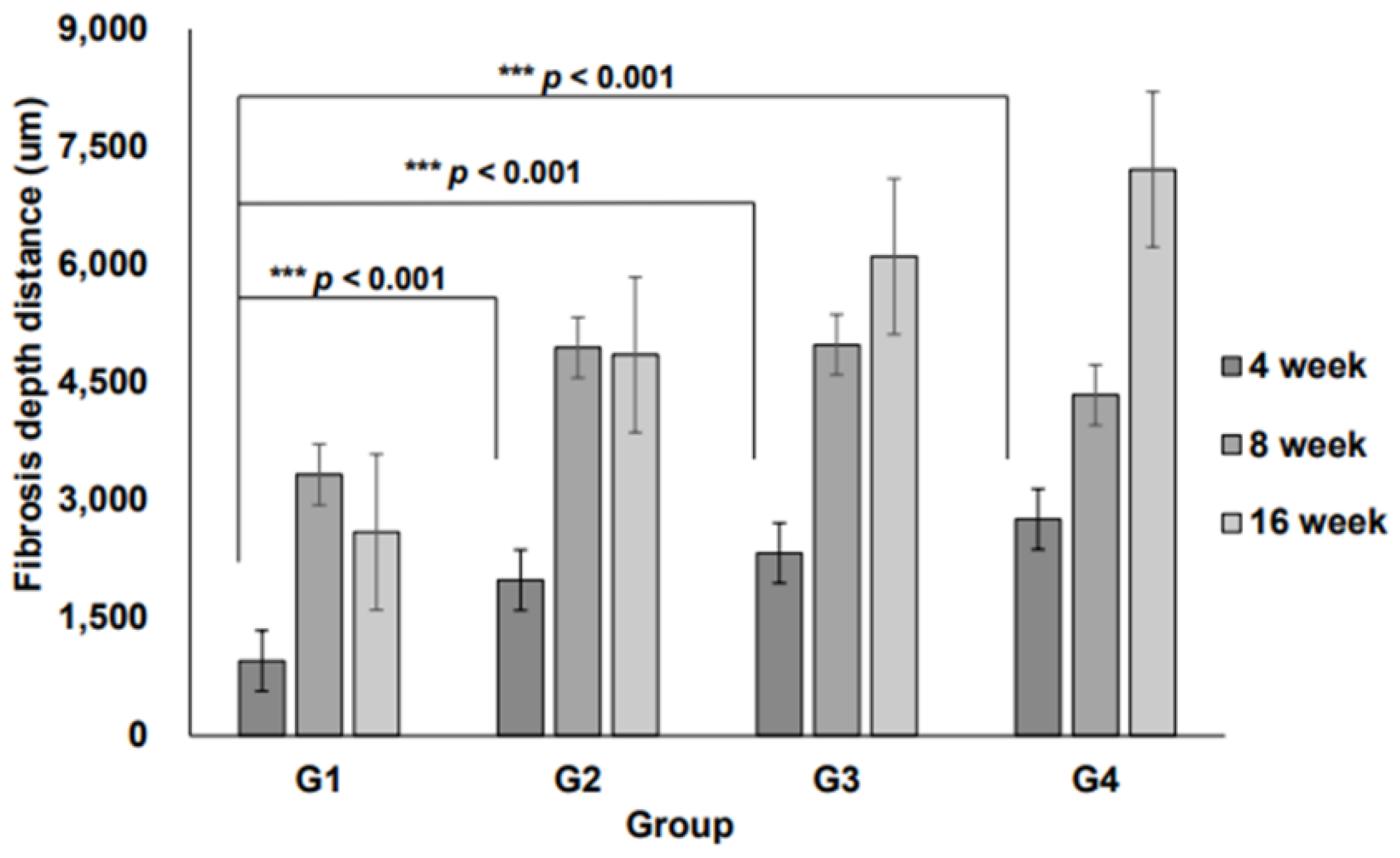

Additionally, the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds were histologically evaluated. At 4, 8, and 16 weeks, no significant differences were observed in the total number of inflammatory cell types (Table 2). Fibrosis depth within the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds showed significant differences between Groups II, III, and IV, with these groups displaying significantly greater fibrosis than Group I (

p < 0.001,

Figure 4), suggesting enhanced scaffold integration and ECM remodeling.

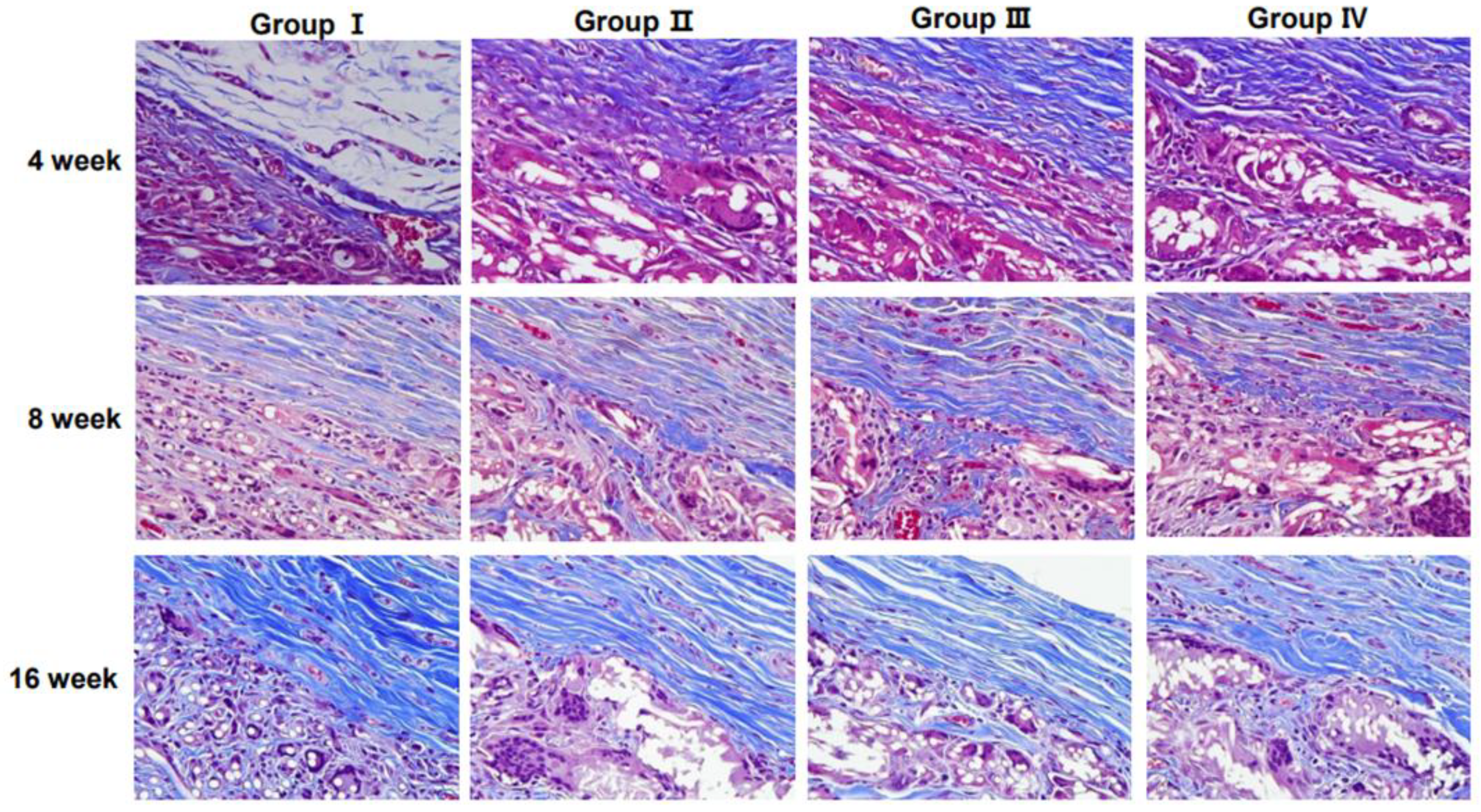

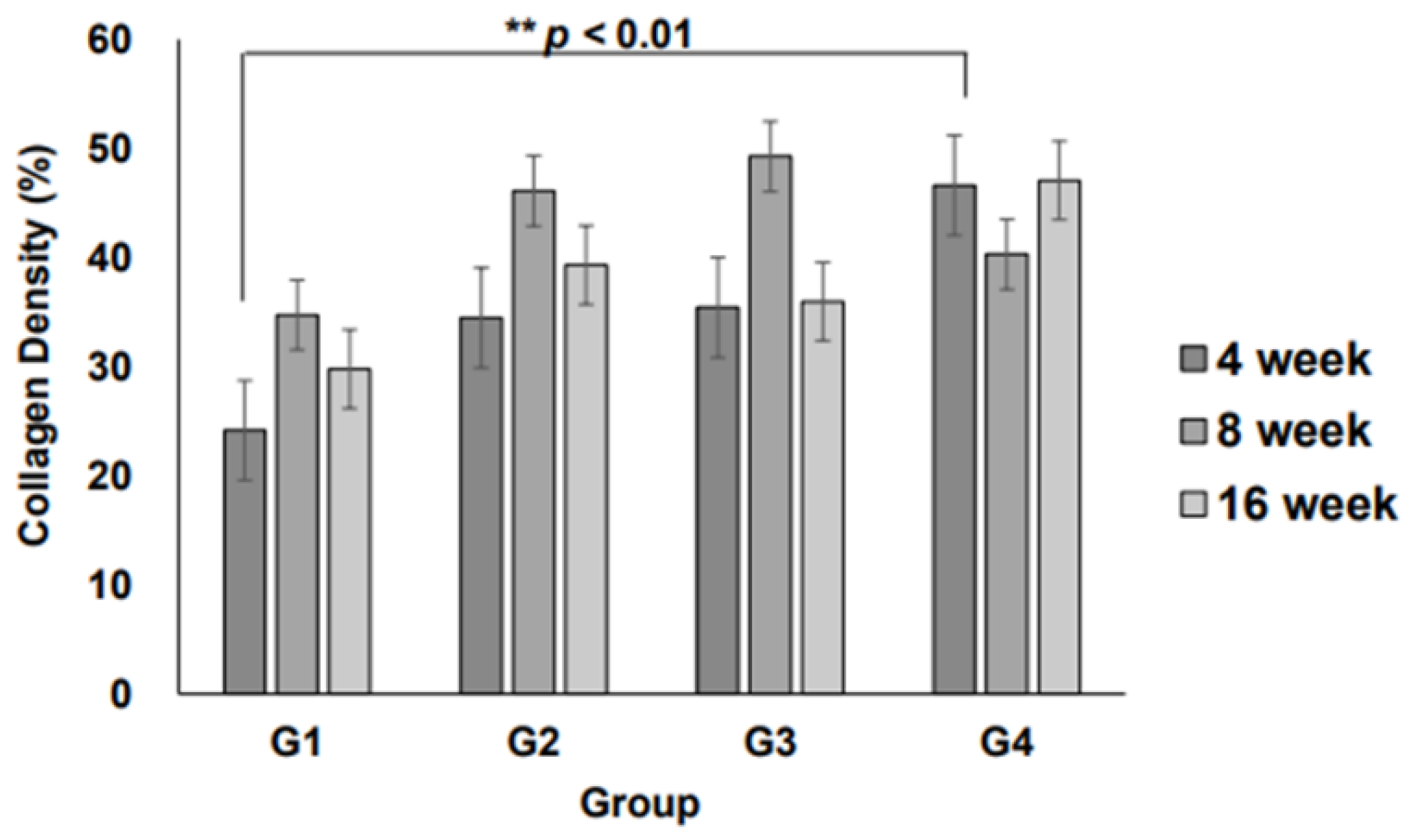

3.3. Collagen Regeneration Within Scaffolds

Collagen content and distribution within the scaffolds were assessed using MT staining (

Figure 5). The staining results demonstrated an increasing trend in collagen deposition over time, particularly in the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffold groups (Groups II, III, and IV).

Quantitative analysis of collagen fiber density revealed that at 4 weeks, collagen deposition was significantly higher in Group IV than in Group I (

p < 0.01,

Figure 6), indicating enhanced ECM formation in the 3D scaffold with the highest weight (0.6 g). At 8 and 16 weeks, the collagen density in all 3D micro-nanofiber scaffold groups (Groups II, III, and IV) remained higher than that in the 2D scaffold group (Group I), although the differences were not statistically significant. Notably, there were no significant differences between the 3D scaffold groups, suggesting that increasing the scaffold weight beyond a certain threshold does not further enhance collagen deposition. These results indicate that 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds promote collagen formation compared with 2D scaffolds, with the most pronounced effect observed at the early stage (4 weeks), particularly in the highest-weight scaffold (Group IV).

4. Discussion

BCS is a widely used surgical intervention for early stage breast cancer that allows patients to retain most of their breast tissue while achieving oncological safety [

7]. However, BCS often results in volume loss, contour irregularities, and fibrosis, leading to aesthetic concerns and patient dissatisfaction. Traditional reconstructive approaches, including fat grafting and synthetic implants, have limitations, such as resorption, donor-site morbidity, and foreign body reactions.

The use of absorbable scaffolds is a promising alternative for promoting endogenous tissue regeneration. The biocompatibility of scaffold materials is crucial to ensure patient safety and minimize adverse effects such as chronic inflammation or fibrosis [

8,

9,

10].

This study aimed to provide a safe and effective solution for breast deformities following BCS using absorbable scaffolds. To evaluate the biocompatibility and regenerative potential of absorbable 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds, we assessed cell infiltration, inflammation, and collagen regeneration.

The observed cell infiltration patterns provided important insights into the biocompatibility and structural characteristics of the different scaffold types. Cell infiltration is a crucial factor in tissue regeneration and varies depending on scaffold structure and pore size. At 4 weeks, Group IV exhibited a tendency towards increased cell infiltration compared with Group I; however, this difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 1). This suggests that while a higher scaffold volume may promote cellular ingress, the volume alone is insufficient to maximize infiltration. Thus, optimizing parameters, such as pore size, density, and physicochemical properties, is essential for enhancing cellular infiltration.

Inflammatory response is a key indicator of how implanted scaffolds interact with the host environment. At 4 weeks, Group IV showed a statistically significant increase in the presence of inflammatory cells compared with Group I, indicating that scaffold structural properties and volume differences may influence immune reactions (

Figure 3A). However, the reduction in inflammatory cells in Group IV at 16 weeks suggested tissue stabilization over time (

Figure 3C). Additionally, at 8 weeks, Group III exhibited increased inflammatory cell infiltration compared with Group I, highlighting the role of the scaffold structure and material properties in modulating immune responses. These findings suggest the necessity of optimizing the scaffold design and degradation processes to minimize localized inflammation. Importantly, the absence of significant differences in inflammatory cell types across different time points (Table 2) implied that scaffold-induced inflammation was localized and did not trigger systemic immune responses.

Collagen fiber density is a critical indicator of ECM synthesis and scaffold-mediated tissue regeneration. At 4 weeks, Group IV exhibited a significantly higher collagen density than Group I, demonstrating its potential to promote ECM formation (

Figure 5). Furthermore, the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds (Groups II, III, and IV) displayed higher collagen fiber density at 8 and 16 weeks than the 2D scaffold (Group I), although the differences were not statistically significant (

Figure 6). This suggests that transitioning from a 2D to a 3D structure may support tissue regeneration; however, further material and structural optimizations are required for consistent outcomes.

Notably, Group IV, which had a relatively higher scaffold volume, exhibited a tendency towards increased ECM formation. However, the absence of significant differences among the 3D scaffold groups suggests that collagen deposition is influenced not only by structural changes but also by factors such as material stiffness, degradation rate, and surface chemistry. Optimizing these parameters is critical for improving scaffold-based tissue regeneration. Additionally, the minimal variation in collagen fiber density among the 3D groups provides a useful reference for determining the maximum applicable volume of the scaffolds. This suggests that exceeding a certain volume threshold may not necessarily enhance ECM formation, emphasizing the importance of defining an optimal scaffold volume to maximize long-term tissue regeneration efficiency.

Further clinical studies are required to validate these findings and to refine the scaffold design for optimized breast tissue regeneration following BCS.

5. Conclusions

This study found that the 3D micro-nanofiber scaffolds promoted cell infiltration, inflammation, and collagen regeneration in a scaffold- and time-dependent manner. Although these scaffolds showed greater cell infiltration and fibrosis depth than the 2D scaffolds at 4 weeks, these differences were not always statistically significant. Inflammation peaked at an early stage, but gradually decreased over time, indicating tissue stabilization. Collagen deposition was higher in the 3D scaffolds, with the largest increase observed in the scaffold with the highest volume. Despite minor variations among the 3D scaffolds, they consistently outperformed the 2D scaffold in promoting collagen regeneration, highlighting their potential for improved tissue integration and ECM formation.

Funding

This study was supported by Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Research Fund (13-2022-0002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC 22-0190-S1A0(2)) of Seoul National University Hospital.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2D |

Two-dimensional |

| 3D |

Three-dimensional |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and eosin |

| MT |

Masson’s trichrome |

References

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice, C.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Barregard, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brenner, H.; Dicker, D.J.; Chimed-Orchir, O.; Dandona, R.; et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017, 3, 524–548. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, F.; Stewart, A.; John, B.; et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2022, 347, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Pappas, L.; Neumayer, L.; Kokeny, K.; Agarwal, J. Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg 2014, 149, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delay, E.; Garson, S.; Tousson, G.; Sinna, R. Fat injection to the breast: Technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthetic Surg J 2009, 29, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayram, Y.; Sezgic, M.; Karakol, P.; Bozkurt, M.; Filinte, G.T. The use of autologous fat grafts in breast surgery: A literature review. Arch Plast Surg 2019, 46, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Hwang, S.; Lim, S.; Eo, S.; Minn, K.W.; Hong, K.Y. Long-term fate of denervated skeletal muscle after microvascular flap transfer. Ann Plast Surg 2018, 80, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, R.K.; Rigotti, G.; Khouri, K.R.; et al. Tissue-engineered breast reconstruction: The next frontier. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015, 135, 1493–1508. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M.F.; Hill, A.D.K.; Quinn, C.M.; McDermott, E.W.; O’Higgins, N. A pathologic assessment of adequate margin status in breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2006, 13, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, R.P.; Myckatyn, T.M. Fat grafting and scaffold-assisted breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 2020, 47, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, S.Y.; Agarwal, J.; Srivastava, A.; et al. Biomaterial scaffolds for tissue engineering in breast reconstruction. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 640207. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).