Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

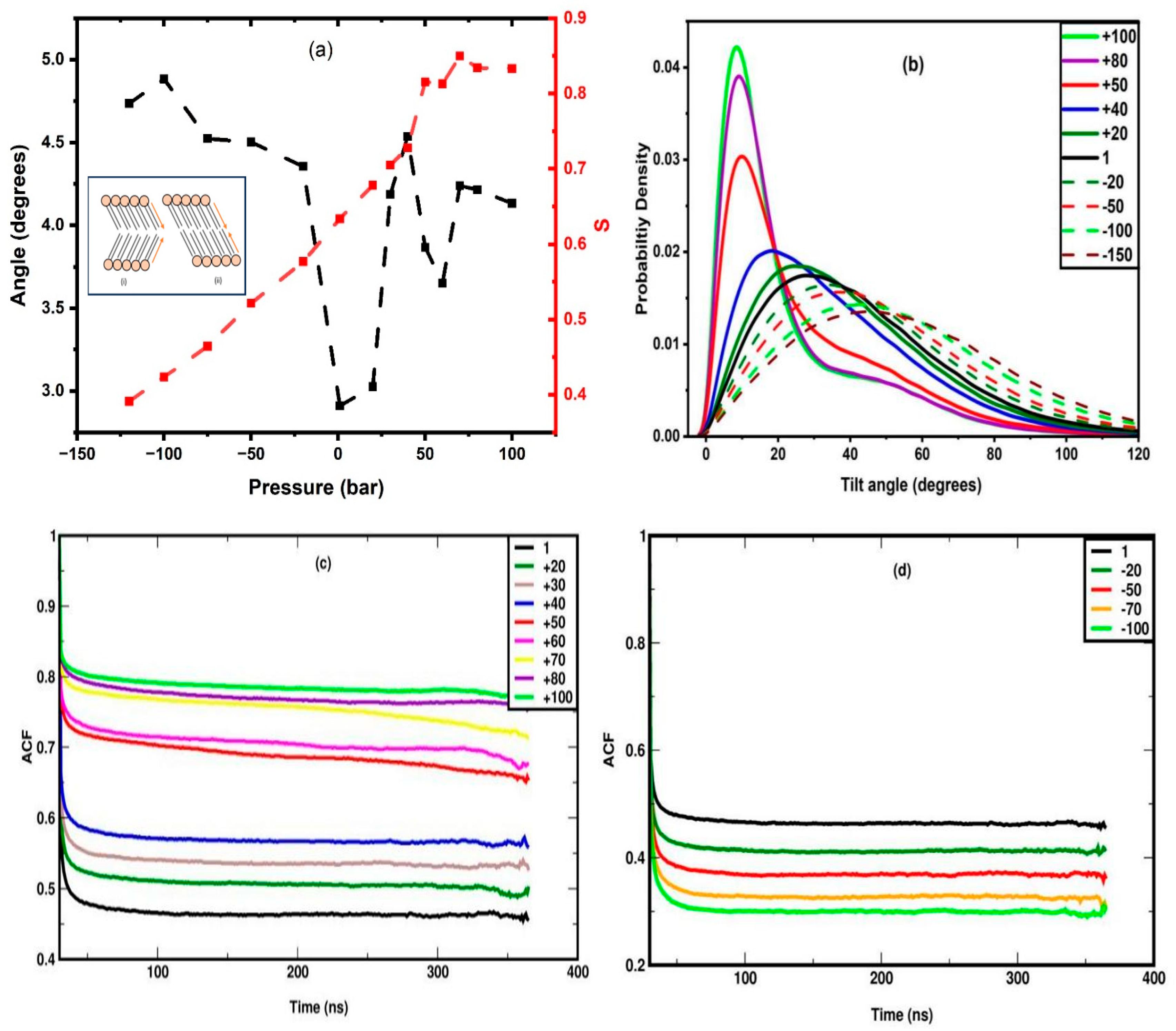

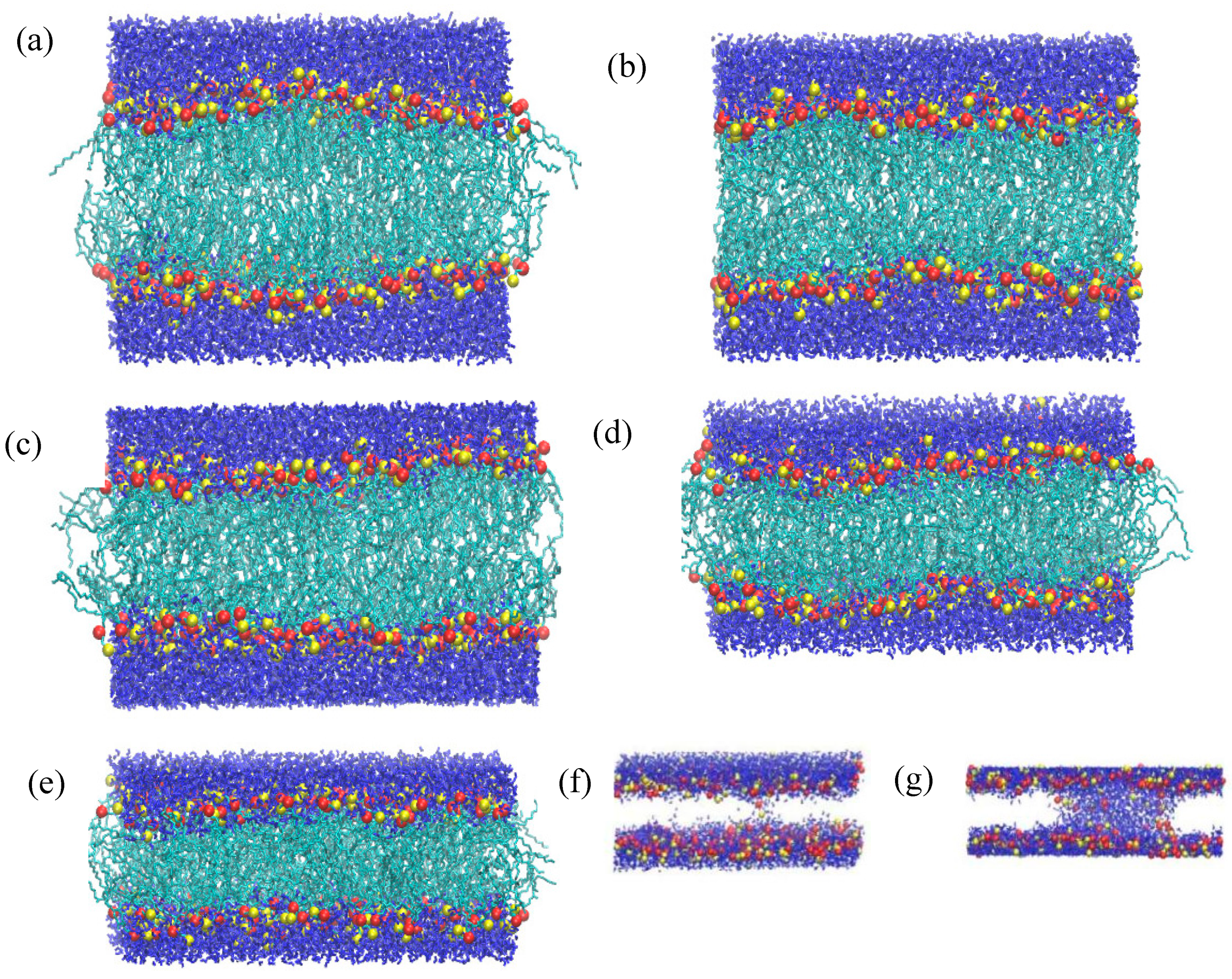

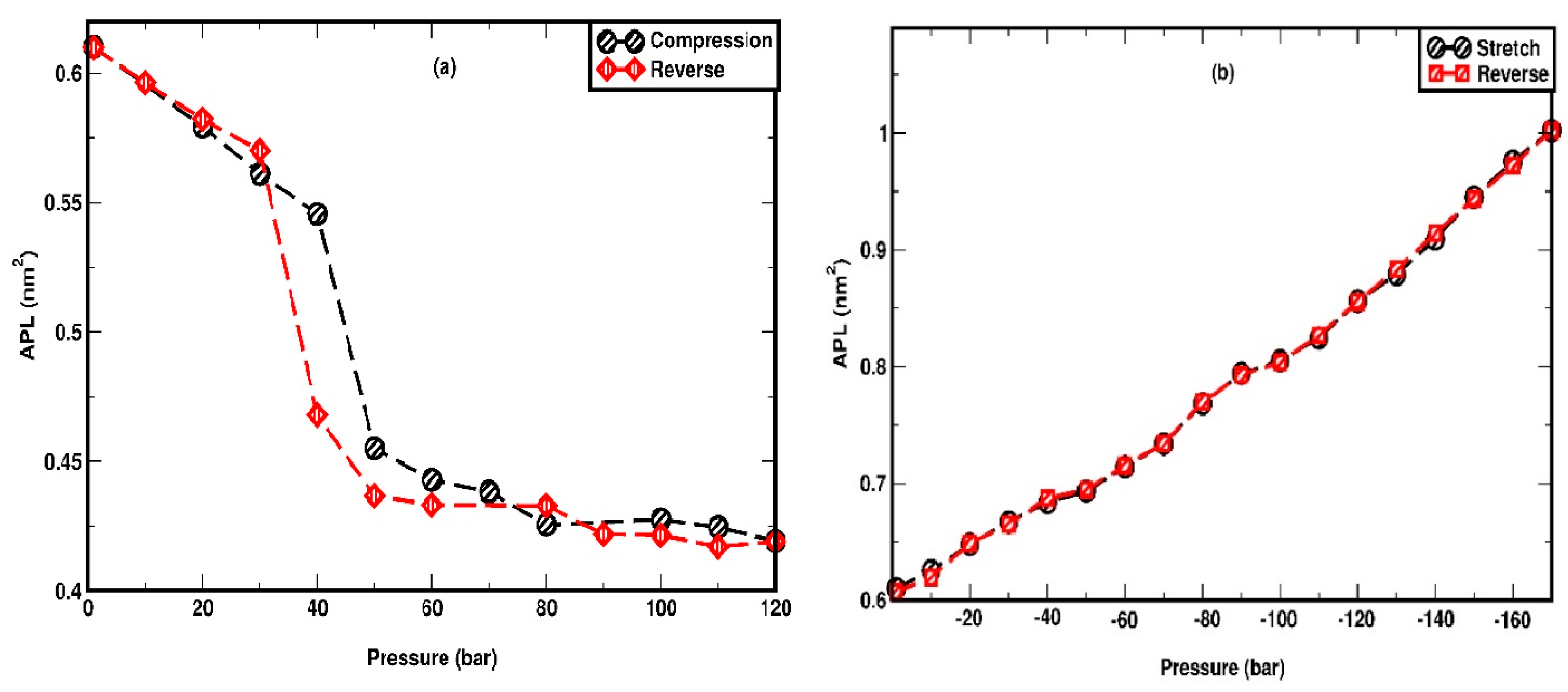

3.1. COMPRESSION

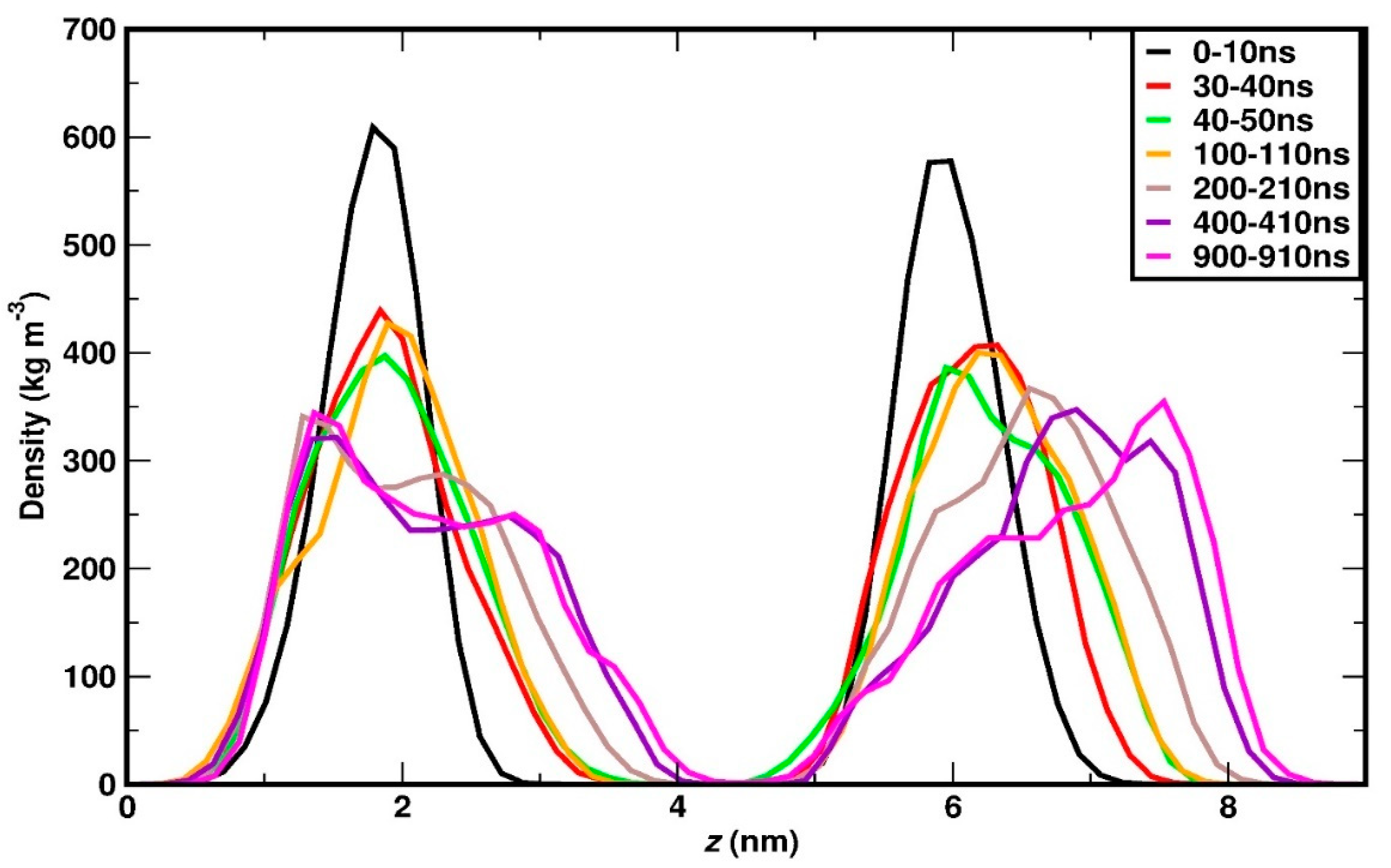

3.2. Stretching

4. Pressure Hysteresis

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Lopes, S. Jakobtorweihen, C. Nunes, B. Sarmento, and S. Reis, “Shedding light on the puzzle of drug-membrane interactions: Experimental techniques and molecular dynamics simulations,” Prog Lipid Res, vol. 65, pp. 24–44, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Sych, C. O. Gurdap, L. Wedemann, and E. Sezgin, “How does liquid-liquid phase separation in model membranes reflect cell membrane heterogeneity?,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 11, no. 5, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, J. Soni, A. Kumar, and T. Mandal, “Origin of the nonlinear structural and mechanical properties in oppositely curved lipid mixtures,” Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 159, no. 16, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Los and N. Murata, “Membrane fluidity and its roles in the perception of environmental signals,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, vol. 1666, no. 1–2, pp. 142–157, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. Peetla, A. Stine, and V. Labhasetwar, “reviews Biophysical Interactions with Model Lipid Membranes : Applications in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery,” no. 4, pp. 8053–8058, 2009.

- E. J. McMurchie and J. K. Raison, “Membrane lipid fluidity and its effect on the activation energy of membrane-associated enzymes,” BBA - Biomembranes, vol. 554, no. 2, pp. 364–374, Jul. 1979. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Niemelä et al., “Membrane proteins diffuse as dynamic complexes with lipids,” J Am Chem Soc, vol. 132, no. 22, pp. 7574–7575, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Garavaglia et al., “Membrane thickness changes ion-selectivity of channel-proteins,” Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, vol. 14, no. 4–6, pp. 231–240, 2004. [CrossRef]

- G. Kasparyan and J. S. Hub, “Molecular Simulations Reveal the Free Energy Landscape and Transition State of Membrane Electroporation,” Phys Rev Lett, vol. 132, no. 14, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. A. L. Filipe, R. M. S. Cardoso, L. M. S. Loura, and M. J. Moreno, “Interaction of Amphiphilic Molecules with Lipid Bilayers: Kinetics of Insertion, Desorption and Translocation,” in Membrane Organization and Dynamics, vol. 20, Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 49–89.

- S. Mallick and N. Agmon, “Lateral diffusion of ions near membrane surface,” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, vol. 26, no. 28, pp. 19433–19449, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Kalutskii, T. R. Galimzyanov, and K. V. Pinigin, “Determination of elastic parameters of lipid membranes from simulation under varied external pressure,” Phys Rev E, vol. 107, no. 2, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Tomasini, C. Rinaldi, and M. S. Tomassone, “Molecular dynamics simulations of rupture in lipid bilayers,” Exp Biol Med, vol. 235, no. 2, pp. 181–188, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Murphy et al., “Molecular dynamics simulations showing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membrane mechanoporation damage under different strain paths,” J Biomol Struct Dyn, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1346–1359, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang et al., “Molecular dynamics simulations of heterogeneous cell membranes in response to uniaxial membrane stretches at high loading rates,” Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Fanani and E. E. Ambroggio, “Phospholipases and Membrane Curvature: What Is Happening at the Surface?,” Feb. 01, 2023, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Knudsen and J. A. Frangos, “Role of cytoskeleton in shear stress-induced endothelial nitric oxide production,” https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H347, vol. 273, no. 1 42-1, 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Gudi, J. P. Nolan, and J. A. Frangos, “Modulation of GTPase activity of G proteins by fluid shear stress and phospholipid composition,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 95, no. 5, pp. 2515–2519, Mar. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Sukharev, P. Blount, B. Martinac, F. R. Blattner, and K. Kung, “A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E.coli encoded by mscL alone,” Nature, pp. 265–268, Mar. 1994. [CrossRef]

- T. Shigematsu, K. Koshiyama, and S. Wada, “Effects of Stretching Speed on Mechanical Rupture of Phospholipid/Cholesterol Bilayers: Molecular Dynamics Simulation,” Scientific Reports 2015 5:1, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Ermakov, “Electric Fields at the Lipid Membrane Interface,” Nov. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- P. Hamill and B. Martinac, “Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells,” Physiol Rev, vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 685–740, 2001. [CrossRef]

- B. Martinac and O. P. Hamill, “Gramicidin A channels switch between stretch activation and stretch inactivation depending on bilayer thickness,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 4308–4312, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Blood, G. S. Ayton, and G. A. Voth, “Probing the molecular-scale lipid bilayer response to shear flow using nonequilibrium molecular dynamics,” Journal of Physical Chemistry B, vol. 109, no. 39, pp. 18673–18679, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Gullingsrud and K. Schulten, “Lipid Bilayer pressure profiles and mechanosensitive channel gating,” Biophys J, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 3496–3509, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. Zhang, J. A. Frangos, and M. Chachisvilis, “Laurdan fluorescence senses mechanical strain in the lipid bilayer membrane,” Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 347, no. 3, pp. 838–841, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Haidekker, T. Ling, M. Anglo, H. Y. Stevens, J. A. Frangos, and E. A. Theodorakis, “New fluorescent probes for the measurement of cell membrane viscosity,” Chem Biol, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 123–131, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Butler, G. Norwich, S. Weinbaum, and S. Chien, “Shear stress induces a time- and position-dependent increase in endothelial cell membrane fluidity,” Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, vol. 280, no. 4, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Allen and D. J. Tildesley, Computer simulation of liquids. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- S. Moradi, A. Nowroozi, and M. Shahlaei, “Shedding light on the structural properties of lipid bilayers using molecular dynamics simulation: a review study,” RSC Adv, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 4644–4658, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Feller, “Molecular dynamics simulations of lipid bilayers,” Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 5, no. 3–4, pp. 217–223, Jul. 2000. [CrossRef]

- H. Fu et al., “Accurate determination of protein:ligand standard binding free energies from molecular dynamics simulations,” Apr. 01, 2022, Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- K. Liu, E. Watanabe, and H. Kokubo, “Exploring the stability of ligand binding modes to proteins by molecular dynamics simulations,” J Comput Aided Mol Des, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 201–211, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Guterres and W. Im, “Improving Protein-Ligand Docking Results with High-Throughput Molecular Dynamics Simulations,” J Chem Inf Model, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 2189–2198, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Karplus and J. Kuriyan, “Molecular dynamics and protein function,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 102, no. 19, pp. 6679–6685, May 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Childers and V. Daggett, “Insights from molecular dynamics simulations for computational protein design,” Feb. 01, 2017, Royal Society of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Pikkemaat, A. B. M. Linssen, H. J. C. Berendsen, and D. B. Janssen, “Molecular dynamics simulations as a tool for improving protein stability,” Protein Eng, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 185–192, 2002.

- Z. Cao et al., “Bias-exchange metadynamics simulation of membrane permeation of 20 amino acids,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 19, no. 3, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Kruszewska, K. Domino, R. Drelich, W. Urbaniak, and A. D. Petelska, “Interactions between beta-2-glycoprotein-1 and phospholipid bilayer—a molecular dynamic study,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 1–19, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Kopec̈, J. Telenius, and H. Khandelia, “Molecular dynamics simulations of the interactions of medicinal plant extracts and drugs with lipid bilayer membranes,” FEBS J, vol. 280, no. 12, pp. 2785–2805, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Ortiz, J. A. Teruel, F. J. Aranda, and A. Ortiz, “On the Mechanism of Membrane Permeabilization by Tamoxifen and 4-Hydroxytamoxifen,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 13, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. S. S. Magalhães, E. D. Vieira, M. R. B. Batista, A. J. Costa-Filho, and L. G. M. Basso, “Effects of Nicotine on the Thermodynamics and Phase Coexistence of Pulmonary Surfactant Model Membranes,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 14, no. 12, p. 267, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. V. Pinigin, “Local Stress in Cylindrically Curved Lipid Membrane: Insights into Local Versus Global Lateral Fluidity Models,” Biomolecules, vol. 14, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Warshaviak, M. J. Muellner, and M. Chachisvilis, “Effect of membrane tension on the electric field and dipole potential of lipid bilayer membrane,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1808, no. 10, pp. 2608–2617, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Kong, S. Qin, D. Lu, and Z. Liu, “Surface tension effects on the phase transition of a DPPC bilayer with and without protein: A molecular dynamics simulation,” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, vol. 16, no. 18, pp. 8434–8440, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Reddy, D. T. Warshaviak, and M. Chachisvilis, “Effect of membrane tension on the physical properties of DOPC lipid bilayer membrane,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1818, no. 9, pp. 2271–2281, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Muddana, R. R. Gullapalli, E. Manias, and P. J. Butler, “Atomistic simulation of lipid and DiI dynamics in membrane bilayers under tension,” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1368–1378, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. J. López Cascales, T. F. Otero, A. J. Fernández Romero, and L. Camacho, “Phase transition of a DPPC bilayer induced by an external surface pressure: From bilayer to monolayer behavior. A molecular dynamics simulation study,” Langmuir, vol. 22, no. 13, pp. 5818–5824, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Leontiadou, A. E. Mark, and S. J. Marrink, “Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Hydrophilic Pores in Lipid Bilayers,” Biophys J, vol. 86, no. 4, p. 2156, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Xie, G. H. Ding, and M. Karttunen, “Molecular dynamics simulations of lipid membranes with lateral force: Rupture and dynamic properties,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1838, no. 3, pp. 994–1002, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Khakbaz and J. B. Klauda, “Investigation of phase transitions of saturated phosphocholine lipid bilayers via molecular dynamics simulations,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1860, no. 8, pp. 1489–1501, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Marrink, J. Risselada, and A. E. Mark, “Simulation of gel phase formation and melting in lipid bilayers using a coarse grained model,” Chem Phys Lipids, vol. 135, no. 2, pp. 223–244, Jun. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. N. van der Veen, J. P. Kennelly, S. Wan, J. E. Vance, D. E. Vance, and R. L. Jacobs, “The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, vol. 1859, no. 9, pp. 1558–1572, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Kučerka, S. Tristram-Nagle, and J. F. Nagle, “Closer look at structure of fully hydrated fluid phase DPPC bilayers,” Biophys J, vol. 90, no. 11, 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. Rossos, S. K. Hadjikakou, and N. Kourkoumelis, “Molecular dynamics simulation of 2-benzimidazolyl-urea with dppc lipid membrane and comparison with a copper(Ii) complex derivative,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 11, no. 10, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, Abraham, Hess, and van der Spoel, “GROMACS 2021.4 Source code”. [CrossRef]

- W. Humphrey, A. Dalke, and K. Schulten, “VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics,” 1996, J. Molec. Graphics.

- J. F. Nagle and S. Tristram-Nagle, “Structure of lipid bilayers,” Biochim Biophys Acta, vol. 1469, no. 3, p. 159, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Marrink, O. Berger, P. Tieleman, and F. Jähnig, “Adhesion forces of lipids in a phospholipid membrane studied by molecular dynamics simulations.,” Biophys J, vol. 74, no. 2 Pt 1, p. 931, 1998. [CrossRef]

- H. J. C. Berendsen, J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, and J. Hermans, “Interaction Models for Water in Relation to Protein Hydration,” pp. 331–342, 1981. [CrossRef]

- B. Hess, H. Bekker, H. J. C. Berendsen, and J. G. E. M. Fraaije, “LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations,” J Comput Chem, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1463–1472, 1997.

- T. Darden, D. York, and L. Pedersen, “Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems,” J Chem Phys, vol. 98, no. 12, pp. 10089–10092, 1993. [CrossRef]

- S. Nosé, “A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods,” J Chem Phys, vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 511–519, 1984. [CrossRef]

- S. Nosé, “A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble,” Mol Phys, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 255–268, 1984. [CrossRef]

- W. G. Hoover, “Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions,” Phys Rev A (Coll Park), vol. 31, no. 3, p. 1695, Mar. 1985. [CrossRef]

- S. Nosé and M. L. Klein, “Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems,” Mol Phys, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 1055–1076, 1983. [CrossRef]

- M. Parrinello and A. Rahman, “Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method,” J Appl Phys, vol. 52, no. 12, pp. 7182–7190, 1981. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Brooks et al., “CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program,” J Comput Chem, vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 1545–1614, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Kučerka, M. P. Nieh, and J. Katsaras, “Fluid phase lipid areas and bilayer thicknesses of commonly used phosphatidylcholines as a function of temperature,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1808, no. 11, pp. 2761–2771, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. A. L. Filipe, L. M. S. Loura, and M. J. Moreno, “Permeation of a Homologous Series of NBD-Labeled Fatty Amines through Lipid Bilayers: A Molecular Dynamics Study,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 13, no. 6, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Z. Xia, S. Cai, S. Xia, and X. Zhang, “The non-thermal influences of ultrasound on cell membrane: A molecular dynamics study,” J Mol Struct, vol. 1299, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Nagle, “Area/lipid of bilayers from NMR.,” Biophys J, vol. 64, no. 5, p. 1476, 1993. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhuang, J. R. Makover, W. Im, and J. B. Klauda, “A systematic molecular dynamics simulation study of temperature dependent bilayer structural properties,” Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, vol. 1838, no. 10, pp. 2520–2529, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Lai, B. Wang, Y. Zhang, and Y. Zhang, “High pressure effect on phase transition behavior of lipid bilayers,” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, vol. 14, no. 16, pp. 5744–5752, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Andrienko, “Introduction to liquid crystals,” J Mol Liq, vol. 267, pp. 520–541, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Martínez-Fernández, M. Herranz, K. Foteinopoulou, N. C. Karayiannis, and M. Laso, “Local and Global Order in Dense Packings of Semi-Flexible Polymers of Hard Spheres,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Martínez-Fernández, C. Pedrosa, M. Herranz, K. Foteinopoulou, N. C. Karayiannis, and M. Laso, “Random close packing of semi-flexible polymers in two dimensions: Emergence of local and global order,” Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 161, no. 3, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Leekumjorn and A. K. Sum, “Molecular studies of the gel to liquid-crystalline phase transition for fully hydrated DPPC and DPPE bilayers,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, vol. 1768, no. 2, pp. 354–365, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Hofsäß, E. Lindahl, and O. Edholm, “Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Phospholipid Bilayers with Cholesterol,” Biophys J, vol. 84, no. 4, p. 2192, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- W. Kulig et al., “How well does cholesteryl hemisuccinate mimic cholesterol in saturated phospholipid bilayers?,” J Mol Model, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 1–9, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Qin, Z. W. Yu, and Y. X. Yu, “Structural characterization on the gel to liquid-crystal phase transition of fully hydrated DSPC and DSPE bilayers,” J Phys Chem B, vol. 113, no. 23, pp. 8114–8123, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Berger, O. Edholm, and F. Jähnig, “Molecular dynamics simulations of a fluid bilayer of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine at full hydration, constant pressure, and constant temperature,” Biophys J, vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 2002–2013, 1997. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun and R. A. Böckmann, “Membrane phase transition during heating and cooling: molecular insight into reversible melting,” European Biophysics Journal, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 151–164, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Meleleo, “Study of resveratrol’s interaction with planar lipid models: Insights into its location in lipid bilayers,” Membranes (Basel), vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1–17, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Guo, C. Peschel, T. Watermann, G. F. von Rudorff, and D. Sebastiani, “Cluster formation of polyphilic molecules solvated in a DPPC bilayer,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Neupane, G. Cordoyiannis, F. U. Renner, and P. Losada-Pérez, “Real-Time monitoring of interactions between solid-supported lipid vesicle layers and shortand medium-chain length alcohols: Ethanol and 1-pentanol,” Biomimetics, vol. 4, no. 1, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dai, Z. Xie, and L. Liang, “Pore Formation Mechanism of A-Beta Peptide on the Fluid Membrane: A Combined Coarse-Grained and All-Atomic Model,” Molecules, vol. 27, no. 12, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yin, X. Shi, H. Ding, X. Dai, G. Wan, and Y. Qiao, “Interactions of borneol with DPPC phospholipid membranes: A molecular dynamics simulation study,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 20365–20381, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Pressure (bar) Low loading |

Simulation Index | Rupture? | Time of rupture (ns) |

| -170 | #1 | No | NA |

| -170 | #2 | No | NA |

| -170 | #3 | No | NA |

| -170 | #4 | No | NA |

| -180 | #1 | Yes | 106 |

| -180 | #2 | Yes | 426 |

| -180 | #3 | Yes | 416 |

| -180 | #4 | No | NA |

| -190 | #1 | Yes | 238 |

| -190 | #2 | Yes | 74 |

| -190 | #3 | Yes | 103 |

| -190 | #4 | Yes | 458 |

| -200 | #1 | Yes | 188 |

| -200 | #2 | Yes | 55 |

| -200 | #3 | Yes | 207 |

| -200 | #4 | Yes | 154 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).