1. Introduction

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation has emerged as a clinically feasible fertility preservation strategy, particularly for cancer patients, women with premature ovarian failure, and women with diminished ovarian function [

1,

2]. It is a critical option for emergency situations and prepubertal patients who are not suitable for oocyte or embryo cryopreservation [

3,

4]. Despite advances in cryopreservation and thawing methods, ovarian tissue still presents varying degrees of damage after cryopreservation (freezing and thawing), including damage to follicles, blood vessels, and stromal cells, which may compromise its functional integrity. In vitro culture of ovarian tissue after cryopreservation has shown the potential to enhance follicular viability and promote ovarian tissue recovery, highlighting its importance in optimizing fertility outcomes [

5,

6].

In vitro culture of ovarian tissue includes various methods, two-dimensional (2D) culture, three-dimensional (3D) suspension culture, microfluidic culture, and 3D scaffold-based culture [

7]. The 2D culture method presupposes a placing of ovarian tissue fragments in a culture dish with medium. However, the lack of a 3D structural environment limits follicular development. In contrast, 3D suspension culture preserves tissue architecture and enhances follicular survival and maturation by preventing of adhesion. In the same time, structural instability of cells remains a challenge. Microfluidic culture, using of microfluidic chips for precise control of nutrient supply, is well-suited for long-term culture but the limitation is its technical complexity and high cost. The 3D scaffold culture method presupposes a putting of ovarian tissue into natural or synthetic biomaterials, facilitating cell-cell interactions, improving of follicular viability, and advancing of artificial ovary development. The selection of appropriate biomaterials is crucial, as they significantly influence tissue functionality and developmental outcomes [

8,

9,

10].

3D scaffolds provide a structural framework that mimics the extracellular matrix, supporting cell attachment, proliferation, differentiation, and tissue formation. Various scaffold materials, including natural, synthetic, and composite biomaterials, each have different advantages and limitations [

11,

12,

13].

Among them, the composite material TISSEEL Fibrin has shown good potential. TISSEEL Fibrin is composed of two key components, which polymerize into a fibrin clot after activation, have excellent biocompatibility, provide structural support, and gradually degrade, making it a viable option for 3D scaffolds [

14,

15].

In previous studies, 3D scaffold culture based on TISSEEL Fibrin successfully supported ovarian tissue development. In about seven days, primordial follicles were activated and developed into secondary follicles, and the artificial ovarian structure showed signs of degradation over time, demonstrating its good properties [

16]. In addition to in vitro culture applications, a minimizing of mechanical damage during ovarian transplantation is critical to optimize ovarian tissue viability and function [

17]. TISSEEL fibrin exhibits adhesive properties that may serve as an alternative to suture fixation during ovarian transplantation. By minimizing of tissue compression and mechanical stress, it has the potential to reduce transplant-related damage and support ovarian tissue integration and development.

In this study, transcriptomic analysis was used to comprehensively evaluate the advantages and limitations of TISSEEL-based 3D scaffold culture with the goal of optimizing the method for in vitro culture of ovarian tissue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Experiments

A total of twelve ovarian tissue samples were collected, cryopreserved (frozen and thawed) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], and evaluated. Four groups were formed. Group 1: quick thawing of frozen ovarian tissue in boiling water (100°C). Group 2: quick thawing of frozen ovarian tissue in boiling water (100°C) and evaluated after 7 days of in vitro 3D culture. Group 3: slow thawing of frozen ovarian tissue in 37°C water. Group 4: slow thawing of frozen ovarian tissue in 37°C warm water and evaluated after 7 days of in vitro 3D culture. Three samples in each experimental group were used (

Figure 1).

2.2. Collection of Samples and Cryopreservation (Freezing and Thawing)

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Cologne University (applications 999,184 and 13-147) and by the Bulgarian Ethics Committee. The informed consent was obtained from patients whose ovarian tissue was collected for this study. Unless specified otherwise, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cryopreservation (freezing and thawing) of ovarian tissue was performed according to our previously published protocol [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. On the day of freezing, ovarian tissue fragments were placed in 20 mL of freezing medium at room temperature, which consisted of basal medium supplemented with 6% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 6% ethylene glycol, and 0.15 M sucrose. Tissue fragments were then transferred to standard 5 mL cryovials (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA), prefilled with freezing medium, and frozen using an IceCube 14S freezer (SyLab, Neupurkersdorf, Austria). The cryopreservation protocol was as follows: (1) starting temperature was −8°C; (2) samples were cooled from −8°C to −34°C at a rate of 0.3°C/min; and (3) at −34°C, the cryovials were placed in liquid nitrogen. The freezing protocol also included an automated seeding step at −8°C.

Quick thawing: Tissue thawing was achieved by placing the cryovials at room temperature for 30 seconds, then immersing them in a 100°C (boiling water) water bath for 60 seconds and draining the contents of the tubes into a solution to remove the cryoprotectant. The exposure time in boiling water was visually controlled by the presence of ice in the culture medium; once the ice reached a size of 2 to 1 mm, the tubes were removed from the boiling water, at which point the final temperature of the culture medium was between 4 and 10°C. Within 5 to 10 seconds of thawing, the tissue fragments in the cryovials were drained into 10 mL of thawing solution (basal medium containing 0.5 M sucrose) in a 100 mL specimen container (Sarstedt, Neumbrecht, Germany). After 15 minutes of exposure of the tissue to sucrose, the cells were rehydrated stepwise as previously reported [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Slow Thawing: This thawing method is the same as the quick thawing method above, except that the tissue is thawed by immersing the cryovial in a 37°C water bath for 3 minutes until the ice has completely melted.

2.3. 3D In Vitro Culture with TISSEEL Fibrin Sealant

TISSEEL fibrin sealant (Baxter International Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA) was used to encapsulate ovarian tissue for subsequent in vitro culture and analysis. The fibrin sealant contains two main components: thrombin and fibrinogen, with final concentrations of 10 IU/mL and 45.5 mg/mL, respectively, to achieve optimal gel formation and encapsulation. The two components were quickly mixed in an Eppendorf tube using a pipette and vortexed. Then 100 µL of the solution was dropped onto the ovarian tissue to form a nearly gel-like mixture. After gelation was complete, the formed fibrin gel was gently peeled off using sterile forceps to avoid any damage to the tissue during in vitro culture. The encapsulated tissue was then immediately transferred to a 700 mL cell culture flask (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) containing 70 mL of culture medium. Seven-day cultures of ovarian tissue were performed in α-modified Eagle’s minimum essential medium (α-MEM, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL penicillin. The culture was placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and agitated at 75 times per minute using a rotary shaker.

2.4. Histological Analysis

Ovarian tissues were fixed in 3.5% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C and then embedded in paraffin. Four µm thick sections were cut, and every 10th section was mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Morphological analysis of tissue development and viability was performed under a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope at 200x and 400x magnification.

2.5. Sequencing and Data Extraction

RNA extraction was performed for each ovarian tissue sample using the Trizol method. RNA integrity was assessed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Messenger RNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligonucleotide-linked magnetic beads. After fragmentation, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers. Second-strand cDNA was then synthesized using dUTP instead of dTTP. After end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, size selection, amplification, and purification, the directional library was ready. The library was checked for quantification using Qubit and real-time PCR, and size distribution was detected using a bioanalyzer. After library quality control, different libraries were pooled together based on effective concentration and target data volume, and then subjected to Illumina sequencing. The basic principle of sequencing is “sequencing by synthesis”, where fluorescently labeled dNTPs, DNA polymerase, and adapter primers are added to the sequencing flow cell for amplification. As each sequencing cluster extends its complementary chain, the addition of each fluorescently labeled dNTP releases a corresponding fluorescent signal. The sequencer captures these fluorescent signals and converts them into sequencing peaks by computer software to obtain the sequence information of the target fragments. The reference genome and gene model annotation files were downloaded directly from the genome website. The index of the reference genome was built using Hisat2 v2.0.5, and the paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. We chose Hisat2 as the mapping tool because Hisat2 can generate a splice site database based on the gene model annotation file, so the mapping results are better than other non-splicing mapping tools. The mapped reads of each sample were assembled by StringTie (v1.3.3b) (Mihaela Pertea. et al. 2015) in a reference-based approach. StringTie uses a novel network flow algorithm with an optional de novo assembly step to assemble and quantify full-length transcripts representing multiple splice variants for each gene locus.

2.6. Differential Expression Analysis

For DESeq2 with biological replicates: Differential expression analysis of two conditions/groups was performed using the DESeq2 R package (1.20.0). DESeq2 provides statistical procedures to determine differential expression in digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P values were adjusted using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg to control the false discovery rate. Corrected P values ≤ 0.05 and |log2(foldchange)| ≥ 1 were set as thresholds for significant differential expression.

2.7. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

KEGG is a database resource for understanding the high-level functions and utility of biological systems (e.g., cells, organisms, and ecosystems) from molecular-level information, especially large-scale molecular datasets generated by genome sequencing and other high-throughput experimental technologies (

http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). We used the R package cluster profile to test the statistical enrichment of differentially expressed genes in KEGG pathways.

2.8. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) is a computational method used to determine whether predefined gene sets can show significant consistent differences between two biological states. Genes are ranked according to the degree of differential expression in the two samples, and then predefined gene sets are tested to see if they are enriched at the top or bottom of the list. Gene set enrichment analysis can include subtle expression changes. We used a local version of the GSEA analysis tool

http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp, and the KEGG datasets were used for GSEA separately.

3. Results

3.1. Morphology

Ovarian tissue after quick thawing was well encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin Sealant, displaying a 3D full-surround effect (

Figure 2A1, A2, and 2A3). It was detected similarly well-wrapped the slow thawing ovarian tissue with TISSEEL Fibrin Sealant (

Figure 2B1, B2, and B2). In

Figure 2C1, C2, and C3, after quick thawing and 7 days in vitro culture, the ovarian tissue turns light yellow that indicate a cellular adaptation.

Figure 2D1, D2, and D3 also show a similar color change of tissues after slow thawing and culture.

Figure 3A,B display hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of ovarian tissues that underwent quick thawing without following in vitro culture.

Figure 3C,D present HE-stained sections of ovarian tissues subjected to quick thawing followed by a seven-day in vitro 3D culture. Notably, the follicle cells showed significant development, actively migrating into and growing and developing within the fibers. Before cryopreservation, the ovarian medulla was partially removed to minimize the formation of intracellular ice crystals. Therefore, these sections have not shown mature follicles or secondary oocytes, only limited primordial follicles which are a basis for future ovarian tissue development. The similar results are shown in

Figure 3E–H. Compared to those observed in

Figure 3E,F of slow-thawed tissue that was not cultured,

Figure 3G,H illustrate the results of slow-thawed cryopreserved ovarian tissue after culture. Follicle cells showed significant development, actively migrating into and growing and developing within the fibers. These results may suggest that in vitro 3D culture can effectively promote the growth, development, and migration of follicle cells.

3.2. Differential Expression Genes (DEGs)

The heatmap of DEGs is shown in

Figure 4. Volcano plots were generated to compare the up-regulated and down-regulated differentially expressed genes in the tissues of different groups. Comparison of cells in Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing of ovarian tissue without culture), 6903 genes were up-regulated and 7819 genes were down-regulated in groups 2 and 4 (thawing with in vitro 3D culture), as shown in

Figure 5A. Compared with Group 1 (quick thawing), 5533 genes were up-regulated and 5482 genes were down-regulated in cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with in vitro 3D culture), as shown in

Figure 5B. Meanwhile, compared with cells of Group 3 (slow thawing), 6015 genes were up-regulated and 6175 genes were down-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with in vitro 3D culture), as shown in

Figure 5C. Compared with cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with in vitro 3D culture), 2192 genes were up-regulated and 2014 genes were down-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with in vitro 3D culture), as shown in

Figure 5D.

3.3. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis based on DEGs. In comparison to Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing of ovarian tissue without culture), DEGs in cells of Group 2 and Group 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture), are mainly enriched and up-related in the lysosome pathway and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway (

Figure 6A) and mainly down-related in the cell adhesion molecules pathway (

Figure 6B). Compared to cells of Group 1(quick thawing), DEGs in cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) are also mainly enriched and up-related in the lysosome pathway and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway (

Figure 6C) and mainly down-related in the cell adhesion molecules pathway (

Figure 6D). Compared to cells of Group 3 (slow thawing), DEGs in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) are also mainly enriched and up-related in the lysosome pathway and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway (

Figure 6E) and mainly down-related in the cell adhesion molecules pathway (

Figure 6F).

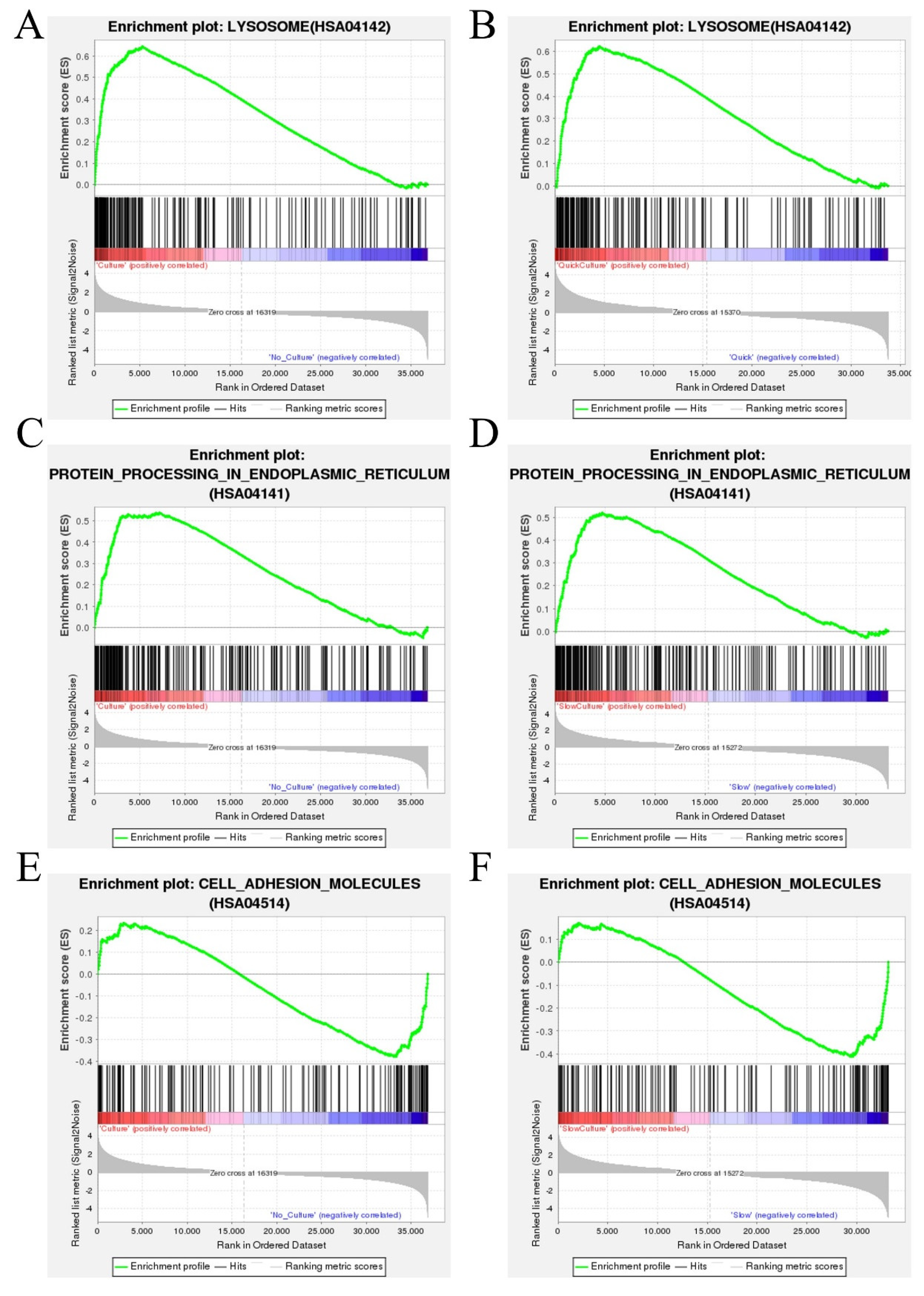

3.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

GSEA is an in-depth data analysis based on predefined gene sets in the KEGG database. In comparison to cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing of ovarian tissue without in vitro 3D culture culture), enrichment of genes involved in the lysosome pathway in upregulation in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing with culture) (

Figure 7A). The enrichment of genes involved in the lysosome pathway in upregulation also in cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) compared to cells of Group 1(quick thawing) (

Figure 7B). It is shown that the expression of the lysosomal pathway in thawed ovarian tissue with followed in vitro 3D culture was significantly upregulated compared to that cells after thawing without culture.

Meanwhile, compared to groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture), enrichment of genes involved in the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway in upregulation in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing with culture) (

Figure 7C). The enrichment of genes involved in the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway in upregulation is also in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) compared to cells of Group 3 (slow thawing) (

Figure 7D. It is shown that the expression of the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway in thawing ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture was significantly upregulated compared to that in thawing ovarian tissue without culture.

Compared to cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture), cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing with culture) shown downregulation of genes involved in the cell adhesion molecules pathway (

Figure 7E), and compared to cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with culture), cells of Group 3 (slow thawing) also shown downregulation of genes involved in the cell adhesion molecules pathway (

Figure 7F). It is noted that the expression of the cell adhesion molecules pathway in thawing ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture was significantly downregulated compared to that in thawing ovarian tissue without culture.

3.5. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)

SNP is the detector of a single nucleotide in the genome, typically found in more than 1% of a population. They can be of two types: transitions, where similar bases (A to G or C to T) are substituted, and transversions, where different base types (such as A to C or G to T) are substituted, with transitions being more common. SNPs often occur in methylated CG sequences, leading to C-to-T transitions. In contrast, Insertions and Deletions (INDELs) involve the insertion or deletion of one or more nucleotides and typically result in larger sequence changes compared to SNPs. Both SNPs and INDELs are crucial in studies of gene expression and disease.

In described research it was indicated that there were some mutations has affected the phenotype after in vitro 3D culture of tissue in contrast with tissues evaluated just after thawing. For the respective analysis (

Figure 8) the tissues of both groups were connected because our previous experiments are detected that in appearance of SNR in cells of both groups there is no differences.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of In Vitro 3D Culture on Follicle Growth in Ovarian Tissue

The primary goal of in vitro culture after ovarian tissue cryopreservation (freezing and thawing) is to preserve ovarian tissue function and enhance follicle growth, which is essential for successful transplantation. However, development of follicles is critical by in vitro culture [

23,

24].

In the natural ovarian microenvironment, inhibitory factors such as anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) maintain primordial follicles in a dormant state. However, in vitro culture may weaken these inhibitory signals, leading to premature follicle activation [

25,

26]. Additionally, high-glucose culture media accelerates ovarian tissue metabolism, further promoting follicular development.

3D culture systems provide a spatially supportive environment for follicular growth, facilitating interactions between granulosa cells and oocytes while preserving the microenvironment necessary for normal development. TISSEEL Fibrin, used in our study, mimics the ovarian extracellular matrix, offering a stable 3D scaffold that maintains follicular architecture and enhances follicle survival rates.

Results of our experiments demonstrated that in vitro 3D culture with TISSEEL Fibrin promotes follicular growth in ovarian tissue. As shown in

Figure 3, in tissues of control groups (without in vitro culture) it was found only a small number of primordial follicles. However, after 3D in vitro culture, number of follicles increased significantly, with clear evidence of follicular development. Notably, in certain areas, a follicle colony phenomenon, which is multifollicular development, is observed. It can be characterized by the simultaneous development of multiple follicles close.

While follicular growth and development are beneficial, excessive follicle activation and clustering may accelerate follicle depletion. The early transplantation of dominant follicles or their selection for IVF could be advantageous. However, for long-term follicular viability after transplantation of ovarian tissue, minimizing excessive follicle activation during in vitro culture is critical [

27].

The formation of follicle colonies may lead to competition for nutrients, potentially causing metabolic insufficiency, impaired growth, and apoptosis at later stages. The addition of localized inhibitory factors, such as AMH, during culture, may help regulate follicular activation, mitigating excessive simultaneous development while supporting controlled follicle maturation [

26].

As shown in the KEGG pathway (

Figure 5) both quick and slow thawing methods resulted in significant upregulation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein synthesis pathway in ovarian tissues compared to the tissue from uncultured groups. This finding was further supported by the GSEA analysis (

Figure 6), which confirmed the significant activation of ER protein synthesis. The ER protein synthesis pathway can promote signal recognition, translocation, folding, modification, and quality control of newly synthesized proteins, and plays a key role in follicular development and hormone receptor synthesis. When external conditions are changeing, the ER may undergo a stress response to enhance cell adaptability. Under ER stress conditions, cells with excessive misfolded proteins undergo apoptosis, while others activate adaptive mechanisms to enhance survival [

28,

29,

30]. The upregulation of ER protein synthesis suggests heightened cellular metabolism and active tissue growth, aligning with the observed morphological adaptations.

4.2. Effects of In Vitro 3D Culture on Cell Adhesion

The main advantage of in vitro 3D culture over 2D culture is that it provides a spatially structured environment that preserves natural adhesion between cells, which is essential for follicular development [

31,

32]. Cell adhesion molecules, especially cadherins, play a vital role in mediating cell-cell adhesion, maintaining tissue structure, and regulating cell function [

33]. In ovarian tissue culture, cadherins promote interactions between oocytes and granulosa cells, thereby preserving follicular structure and function [

34]. Therefore, ensuring that the 3D scaffold structure is stable and maintaining cell adhesion is essential to support follicle growth.

In addition, TISSEEL Fibrin in 3D culture can act as a seamless tissue adhesive, providing potential support for applications beyond in vitro culture [

35]. During ovarian transplantation, minimizing mechanical damage is essential for successful implantation of tissues. Whether the fibrin-based 3D culture system can be directly transplanted into body patients, thereby reducing the need for suturing, limiting mechanical trauma, and promoting seamless integration of ovarian tissue with the host environment is what we want to achieve.

Our study found that in vitro 3D culture with TISSEEL Fibrin weakened cell adhesion in ovarian tissue. HE-stained sections of uncultured ovarian tissue in the control group showed tight cell junctions (

Figure 3). However, after 7 days of in vitro 3D culture with TISSEEL Fibrin, cell junctions were significantly weakened, and intercellular gaps became more obvious.

Our in vitro 3D culture is designed to preserve the spatial structure of ovarian tissue. Too tight adhesion in uncultured tissue may hinder the growth of follicles, but excessive relaxation of cell junctions observed after culture, may impair nutrient transport, which is essential for the development of follicles. Tissue relaxation may result from prolonged culture duration, inadequate nutrient supply, or an imbalance in the proliferation rates of follicles and surrounding stromal cells. Additionally, a slight reduction in fibrin was observed after culture, indicating its gradual degradation during the culture period. This fibrin loss may contribute to the collapse of the 3D scaffold, leading to structural instability, disruption of the intercellular space, and weakening of cell adhesion.

In addition, follicular cells showed a tendency to grow into fibrin colloids, indicating potential follicular migration. Some follicles developed in residual colloids, suggesting that in addition to providing structural support, fibrin-based 3D scaffolds can promote follicle migration (

Figure 3B). If such scaffolds are applied in vivo, they may accelerate the integration of transplanted ovarian tissue into the host environment.

As shown in the KEGG pathway analysis (

Figure 5) the cell adhesion molecule pathway was significantly downregulated in cultured ovarian tissue compared to uncultured tissue, regardless of whether a quick or slow thawing method was applied. The GSEA analysis (

Figure 6) further confirmed this downregulation. A reduction in cell adhesion molecules weakens cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, potentially compromising cellular morphology and tissue integrity, and, in severe cases, leading to cell disintegration [

36]. This decline in adhesion molecules may be associated with alterations in the extracellular matrix composition. As culture time increases, follicular cell proliferation and ovarian microenvironmental changes may further impact the 3D culture system. Optimizing culture duration could mitigate these effects. Additionally, increased cellular metabolism within the tissue may result in nutrient depletion, inducing cellular stress and further reducing the expression of cell adhesion molecules. The addition of appropriate cell adhesion molecules to the culture medium may enhance its structural stability.

4.3. Effects of In Vitro 3D Culture on Cell Damage

During the in vitro culture of ovarian tissue, cell damage is a common issue. Irreversible damage, caused by factors such as hypoxia, malnutrition, accumulation of metabolic waste, or mechanical damage, can further induce cell autophagy, eventually leading to cell necrosis [

37,

38,

39].

In our study it was observed that prior to culture, the ovarian tissue appeared light pink, indicating a rich internal blood supply and healthy tissue condition (

Figure 2). After 7 days of culture, the tissue color changed to light yellow, suggesting that the internal blood supply was compromised, potentially due to ischemia and hypoxia. HE-stained sections revealed significant follicular cell proliferation and the formation of follicular colonies, which indicated an increase in internal tissue metabolism (

Figure 3). However, this metabolic increase likely resulted in nutrient depletion and inefficient metabolic waste removal. Concurrently, the tissue gaps widened, cell connections weakened, and signs of apoptosis and necrosis were evident.

Several factors may contribute to this situation. First, the absence of follicle activation inhibitors and the optimal growth environment led to the simultaneous activation and development of multiple follicles, which generated an increased demand for nutrients and the production of metabolic waste. The ovarian tissue may have been unable to adapt to this heightened metabolic activity, resulting in cellular apoptosis. Second, the culture time may have been too long.

In our experiments, ovarian tissue was cultured in the medium for 7 days, and although the 3D scaffold mimics the in vivo environment, it does not offer the same precise regulation. Prolonged culture leds to insufficient tissue nutrition, metabolic waste accumulation, and consequent cell apoptosis. Furthermore, the slight reduction in fibrin after culture suggests fibrin loss during the culture period, which may contribute to the collapse of the 3D scaffold, disruption of the intercellular space structure, weakening of cell adhesion, and a decrease in cell supply, further leading to cell apoptosis.

The KEGG pathway analysis (

Figure 5) reveals that, regardless of whether the tissue underwent rapid or slow recovery, the lysosomal pathway in the cultured ovarian tissue was significantly upregulated compared to uncultured tissue. Further confirmation of this upregulation is provided by the GESA analysis (

Figure 6), which underscores the increased activity of the lysosomal pathway in the cultured ovarian tissue. The upregulation of the lysosomal pathway indicates enhanced cellular autophagy. Autophagy is a process by which cells adapt to stress and manage their metabolic needs. Damaged organelles, proteins, and other cellular debris are encapsulated into autophagosomes and subsequently degraded by lysosomes [

40,

41,

42,

43]. This increase in autophagic activity suggests that during the culture, cell metabolism was heightened, triggering cellular stress and activating autophagy mechanisms.

According to the presented above analysis, in the future an appropriate amount of AMH can be added to inhibit the simultaneous activation of follicles, ensuring the growth and development of a certain number of follicles, and reducing metabolic activities in the tissue. It can help to realize a reduction of time of culture to ensure that the tissue is transplanted in a good state and avoid cell stress caused by insufficient nutrient supply. The volume of the 3D scaffold can also be further expanded to ensure the 3D support function during the entire culture process and the natural adhesion state between cells.

5. Conclusions

Technology of the described dynamic in vitro 3D-cultivation of ovarian tissue for 7 days with TISSEEL Fibrin is informative and demonstrates that cryopreservation stimulates folliculogenesis and proliferative properties of the entire tissue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.I., T.G. and Q.K.; methodology, E.I., and C.P.; software, Q.K., and P.T.; validation, Q.K., G.R., and C.P.; formal analysis, C.P., and E.I.; investigation, G.R.; resources, V.I., TG; data curation, E.I., and Q.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.K., and C.P.; writing review and editing, V.I. and P.T.; visualization, E.I., and P.T.; supervision, V.I. and G.R.; project administration, C.P. and V.I.; funding acquisition, Q.K. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Scholarship Council for Qingduo Kong (No. 202308230130) and Cheng Pei (No. 202208080057). It was also supported by the Bulgarian National Science Fund (Grant KP-06-H81/9).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Cologne University (applications 999,184 and 13-147) and by the Bulgarian Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elvira Hilger and Mohammad Karbassian for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fraison, E.; Huberlant, S.; Labrune, E.; Cavalieri, M.; Montagut, M.; Brugnon, F.; Courbiere, B. Live birth rate after female fertility preservation for cancer or haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the three main techniques; embryo, oocyte and ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2023, 38, 489-502. [CrossRef]

- Cacciottola, L.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. Ovarian tissue and oocyte cryopreservation prior to iatrogenic premature ovarian insufficiency. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology 2022, 81, 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, C.E.; Anderson, R.A. Clinical dilemmas in ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Fertility and sterility 2024, 122, 559-564. [CrossRef]

- Gadek, L.M.; Joswiak, C.; Laronda, M.M. Thawing fertility: a view of ovarian tissue cryopreservation processes and review of ovarian transplant research. Fertility and sterility 2024, 122, 574-585. [CrossRef]

- Ghezelayagh, Z.; Khoshdel-Rad, N.; Ebrahimi, B. Human ovarian tissue in-vitro culture: primordial follicle activation as a new strategy for female fertility preservation. Cytotechnology 2022, 74, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Gastal, G.D.A.; Aguiar, F.L.N.; Alves, B.G.; Alves, K.A.; de Tarso, S.G.S.; Ishak, G.M.; Cavinder, C.A.; Feugang, J.M.; Gastal, E.L. Equine ovarian tissue viability after cryopreservation and in vitro culture. Theriogenology 2017, 97, 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Filatov, M.A.; Khramova, Y.V.; Kiseleva, M.V.; Malinova, I.V.; Komarova, E.V.; Semenova, M.L. Female fertility preservation strategies: cryopreservation and ovarian tissue in vitro culture, current state of the art and future perspectives. Zygote (Cambridge, England) 2016, 24, 635-653. [CrossRef]

- Khunmanee, S.; Park, H. Three-Dimensional Culture for In Vitro Folliculogenesis in the Aspect of Methods and Materials. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2022, 28, 1242-1257. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, E.; Wang, Y. Advances in the applications of polymer biomaterials for in vitro follicle culture. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 140, 111422. [CrossRef]

- Brito, I.R.; Lima, I.M.; Xu, M.; Shea, L.D.; Woodruff, T.K.; Figueiredo, J.R. Three-dimensional systems for in vitro follicular culture: overview of alginate-based matrices. Reproduction, fertility, and development 2014, 26, 915-930. [CrossRef]

- He, X. Microfluidic Encapsulation of Ovarian Follicles for 3D Culture. Ann Biomed Eng 2017, 45, 1676-1684. [CrossRef]

- Braccini, S.; Tacchini, C.; Chiellini, F.; Puppi, D. Polymeric Hydrogels for In Vitro 3D Ovarian Cancer Modeling. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Matsushige, C.; Xu, X.; Miyagi, M.; Zuo, Y.Y.; Yamazaki, Y. RGD-modified dextran hydrogel promotes follicle growth in three-dimensional ovarian tissue culture in mice. Theriogenology 2022, 183, 120-131. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M. Fibrin glue. Blood Rev 1991, 5, 240-244. [CrossRef]

- Haase, J. Use of Tisseel in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg 1984, 61, 801. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Pei, C.; Isachenko, E.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Rahimi, G.; Liu, W.; Mallmann, P.; Isachenko, V. Automatic Evaluation for Bioengineering of Human Artificial Ovary: A Model for Fertility Preservation for Prepubertal Female Patients with a Malignant Tumor. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Donfack, N.J.; Alves, K.A.; Araújo, V.R.; Cordova, A.; Figueiredo, J.R.; Smitz, J.; Rodrigues, A.P.R. Expectations and limitations of ovarian tissue transplantation. Zygote (Cambridge, England) 2017, 25, 391-403. [CrossRef]

- Isachenko, V.; Morgenstern, B.; Todorov, P.; Isachenko, E.; Mallmann, P.; Hanstein, B.; Rahimi, G. Patient with ovarian insufficiency: baby born after anticancer therapy and re-transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Journal of ovarian research 2020, 13, 118. [CrossRef]

- Isachenko, V.; Todorov, P.; Isachenko, E.; Rahimi, G.; Hanstein, B.; Salama, M.; Mallmann, P.; Tchorbanov, A.; Hardiman, P.; Getreu, N.; et al. Cryopreservation and xenografting of human ovarian fragments: medulla decreases the phosphatidylserine translocation rate. Reproductive biology and endocrinology: RB&E 2016, 14, 79. [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Todorov, P.; Cao, M.; Kong, Q.; Isachenko, E.; Rahimi, G.; Mallmann-Gottschalk, N.; Uribe, P.; Sanchez, R.; Isachenko, V. Comparative Transcriptomic Analyses for the Optimization of Thawing Regimes during Conventional Cryopreservation of Mature and Immature Human Testicular Tissue. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Isachenko, V.; Lapidus, I.; Isachenko, E.; Krivokharchenko, A.; Kreienberg, R.; Woriedh, M.; Bader, M.; Weiss, J.M. Human ovarian tissue vitrification versus conventional freezing: morphological, endocrinological, and molecular biological evaluation. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2009, 138, 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Todorov, P.; Pei, C.; Isachenko, E.; Rahimi, G.; Mallmann-Gottschalk, N.; Isachenko, V. Positive Effect of Elevated Thawing Rate for Cryopreservation of Human Ovarian Tissue: Transcriptomic Analysis of Fresh and Cryopreserved Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Chavoshinezhad, N.; Niknafs, B. Innovations in 3D ovarian and follicle engineering for fertility preservation and restoration. Molecular biology reports 2024, 51, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wei, F.; Del Valle, J.S.; Stolk, T.H.R.; Huirne, J.A.; Asseler, J.D.; Pilgram, G.S.K.; Van Der Westerlaken, L.A.J.; Van Mello, N.M.; Chuva De Sousa Lopes, S.M. In vitro growth of secondary follicles from cryopreserved-thawed ovarian cortex. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2024, 39, 2743-2753. [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, D.; İncir, S.; Bildik, G.; Taskiran, C.; Oktem, O. In-vitro AMH production of ovarian tissue samples in culture correlates with their primordial follicle pool. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2020, 254, 138-140. [CrossRef]

- Shrikhande, L.; Shrikhande, B.; Shrikhande, A. AMH and Its Clinical Implications. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of India 2020, 70, 337-341. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Kol, S. Ideal frozen embryo transfer regime. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology 2024, 36, 148-154. [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 89-102. [CrossRef]

- Oakes, S.A.; Papa, F.R. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu Rev Pathol 2015, 10, 173-194. [CrossRef]

- Celik, C.; Lee, S.Y.T.; Yap, W.S.; Thibault, G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipids in health and diseases. Prog Lipid Res 2023, 89, 101198. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, O.; Gu, L.; Klumpers, D.; Darnell, M.; Bencherif, S.A.; Weaver, J.C.; Huebsch, N.; Lee, H.P.; Lippens, E.; Duda, G.N.; et al. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity. Nat Mater 2016, 15, 326-334. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Majumder, A. Biomimicked hierarchical 2D and 3D structures from natural templates: applications in cell biology. Biomed Mater 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Bock, E. Cell-cell adhesion molecules. Biochem Soc Trans 1991, 19, 1076-1080. [CrossRef]

- Piprek, R.P.; Kloc, M.; Mizia, P.; Kubiak, J.Z. The Central Role of Cadherins in Gonad Development, Reproduction, and Fertility. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Schlag, G.; Redl, H. Fibrin sealant in orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988, 227, 269-285.

- Ogita, H.; Rikitake, Y.; Miyoshi, J.; Takai, Y. Cell adhesion molecules nectins and associating proteins: Implications for physiology and pathology. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2010, 86, 621-629. [CrossRef]

- Grubliauskaitė, M.; Vlieghe, H.; Moghassemi, S.; Dadashzadeh, A.; Camboni, A.; Gudlevičienė, Ž.; Amorim, C.A. Influence of ovarian stromal cells on human ovarian follicle growth in a 3D environment. Human reproduction open 2024, 2024, hoad052. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, F.; Cacciottola, L.; Yu, F.S.; Barretta, M.; Hossay, C.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. Importance of oxygen tension in human ovarian tissue in vitro culture. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2023, 38, 1538-1546. [CrossRef]

- Takae, S.; Suzuki, N. Current state and future possibilities of ovarian tissue transplantation. Reproductive medicine and biology 2019, 18, 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 648. [CrossRef]

- Glick, D.; Barth, S.; Macleod, K.F. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 2010, 221, 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728-741. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gómez-Sintes, R.; Boya, P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic 2018, 19, 918-931. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Design of experiments.

Figure 1.

Design of experiments.

Figure 2.

Cryopreserved ovarian tissue in vitro 3D culture with TISSEEL Fibrin. (A1–A3) Quick thawing cryopreserved ovarian tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant. (B1-B3) Slow thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant. (C1-C3) Quick thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant and cultured for 7 days. (D1-D3) Slow thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant and cultured for 7 days. Bar = 2.5 mm.

Figure 2.

Cryopreserved ovarian tissue in vitro 3D culture with TISSEEL Fibrin. (A1–A3) Quick thawing cryopreserved ovarian tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant. (B1-B3) Slow thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant. (C1-C3) Quick thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant and cultured for 7 days. (D1-D3) Slow thawed tissue encapsulated in TISSEEL Fibrin sealant and cultured for 7 days. Bar = 2.5 mm.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE)-staining of cryopreserved and in vitro cultured ovarian tissue. (A, B) Group 1 (quick thawed). (C, D) Group 2 (quick thawed and then in vitro 3D cultured). (E, F) HE-staining of Group 3 (slow thawed). (G, H) Group 4 (slow thawed and then in vitro 3D cultured). Bar for (A, E) = 250 µm, Bar for (C,G) = 500 µm, Bar for (B, D, F, H) = 100 µm.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE)-staining of cryopreserved and in vitro cultured ovarian tissue. (A, B) Group 1 (quick thawed). (C, D) Group 2 (quick thawed and then in vitro 3D cultured). (E, F) HE-staining of Group 3 (slow thawed). (G, H) Group 4 (slow thawed and then in vitro 3D cultured). Bar for (A, E) = 250 µm, Bar for (C,G) = 500 µm, Bar for (B, D, F, H) = 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of differential expressed genes (DEGs).

Figure 4.

Heatmap of differential expressed genes (DEGs).

Figure 5.

Volcano map of differential expressed genes (DEGs) (A) DEGs volcano map: Groups 2 and 4 (thawing and then in vitro 3D culture) vs. Groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (B) DEGs volcano map: Group 2 (quick thawing ovarian with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (C) DEGs volcano map: Group 4 (slow thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing). (D) Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. Group 4 (slow thawing with culture).

Figure 5.

Volcano map of differential expressed genes (DEGs) (A) DEGs volcano map: Groups 2 and 4 (thawing and then in vitro 3D culture) vs. Groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (B) DEGs volcano map: Group 2 (quick thawing ovarian with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (C) DEGs volcano map: Group 4 (slow thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing). (D) Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. Group 4 (slow thawing with culture).

Figure 6.

Visualization dot map of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. (A) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: cells of Group 2 and Group 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing without culture). (B) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: cells of Group 2 and Group 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with culture) vs. cells of Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing of ovarian tissue without culture). (C) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: Group 2 (quick thawing of ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (D) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (E) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: Group 4 (slow thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing). (F) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing).

Figure 6.

Visualization dot map of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. (A) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: cells of Group 2 and Group 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing without culture). (B) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: cells of Group 2 and Group 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with culture) vs. cells of Group 1 and Group 3 (thawing of ovarian tissue without culture). (C) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: Group 2 (quick thawing of ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (D) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. Group 1 (quick thawing). (E) KEGG pathway analysis up-related: Group 4 (slow thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing). (F) KEGG pathway analysis down-related: Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) vs. Group 3 (slow thawing).

Figure 7.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) based on KEGG pathway data (A) GSEA analysis indicated the lysosome pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (B) GSEA analysis indicated the lysosome pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. cells of Group 1 (quick thawing). (C) GSEA analysis indicated the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (D) GSEA analysis indicated the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of Group 3 (slow thawing). (E) GSEA analysis indicated the cell adhesion molecules pathway was enriched and down-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing with culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (F) GSEA analysis indicated the cell adhesion molecules pathway was enriched and down-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) vs. cells of Group 3 (slow thawing).

Figure 7.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) based on KEGG pathway data (A) GSEA analysis indicated the lysosome pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing of ovarian tissue with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (B) GSEA analysis indicated the lysosome pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of Group 2 (quick thawing with culture) vs. cells of Group 1 (quick thawing). (C) GSEA analysis indicated the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing ovarian tissue with culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (D) GSEA analysis indicated the protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum pathway was enriched and up-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with in vitro 3D culture) vs. cells of Group 3 (slow thawing). (E) GSEA analysis indicated the cell adhesion molecules pathway was enriched and down-regulated in cells of groups 2 and 4 (thawing with culture) vs. cells of groups 1 and 3 (thawing without culture). (F) GSEA analysis indicated the cell adhesion molecules pathway was enriched and down-regulated in cells of Group 4 (slow thawing with culture) vs. cells of Group 3 (slow thawing).

Figure 8.

Single nucleotide polymorphism based on gene annotation (SNP) in cells of samples from both groups (after in Vitro 3D culture) connected together. (A) Insertion-Deletion (INDEL) impacts the high, low, and moderate hazard number of mutation sites and the number of modification sites. (B) SNP impacts the high, low, and moderate hazard number of mutation sites and the number of modification sites. (C) SNP function showed a single nucleotide change that is a missense mutation, a single nucleotide change that does not cause mutation, and a single nucleotide change that is synonymous mutation. (D) SNP region showed the different sites of mutations.

Figure 8.

Single nucleotide polymorphism based on gene annotation (SNP) in cells of samples from both groups (after in Vitro 3D culture) connected together. (A) Insertion-Deletion (INDEL) impacts the high, low, and moderate hazard number of mutation sites and the number of modification sites. (B) SNP impacts the high, low, and moderate hazard number of mutation sites and the number of modification sites. (C) SNP function showed a single nucleotide change that is a missense mutation, a single nucleotide change that does not cause mutation, and a single nucleotide change that is synonymous mutation. (D) SNP region showed the different sites of mutations.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).