1. Introduction

CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated 9) system has emerged as a revolutionary and powerful tool in the scientific community due to its gene editing potential in multiple cell types and organisms, holding great expectations on therapeutical approaches [

1]. The association of guide RNA (gRNA) and Cas9 enzyme to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is crucial to make cuts in specific locations of DNA sequences, becoming a promising tool in molecular biology and therapeutic research [

2]. However, CRISPR/Cas9 clinical applications present significant challenges, particularly regarding the safe and efficient delivery of its components into target cells with high specificity [

3]. Therefore, research still needs to overcome significant obstacles regarding immune reactions, off-target effects, and suboptimal delivery efficiency.

Gene editing efficiency depends strongly on CRISPR/Cas9 components delivery inside cell nucleus. As a result, different delivery methods to introduce CRISPR/Cas9 into cells and organisms such as viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), exosomes or physical derived technologies have been extensively studied. Consequently, numerous reviews have already been published focusing on CRISPR/Cas9 system but also on different types of delivery methods [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Another important and often-overlooked factor that can influence genome editing efficiency is protein aggregation [

9]. Protein aggregation consists in the abnormal association of proteins creating products that can range from small dimers to large assemblies, which tend to be insoluble and can occur under both, normal physiological conditions and in response to stress such us temperature fluctuations or pH adjustments, as it has been previously studied [

10,

11]. In the context of gene therapy, Cas9 aggregation can lead to the formation of particles which exceed the optimal size range for its delivery inside cells compromising efficiency [

9].

This review was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, focusing on CRISPR/Cas9 delivery, gene therapy vectors, protein stability, and nanoparticle-based approaches. During this process, we noticed that Cas9 aggregation, mentioned in some studies, was not fully studied and explanations on why it occurs and how it affects delivery were avoided. Therefore, this review focuses on cargoes types and delivery vehicles methodologies including physical, viral and non-viral approaches, highlighting innovative delivery systems, their strengths and weaknesses and their efficiency in genome editing. Moreover, we also briefly remark Cas9 aggregation implications in gene editing and delivery efficiency.

2. CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Systems

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing success relies heavily on delivery systems, as it directly influences transfection efficiency, target specificity, and therapeutic potential [

12]. Since CRISPR/Cas9 complex must function on nuclear genome, its components need to be efficiently delivered into the nucleus, which requires overcoming tissues and the cell membrane barriers as well as facing challenges due to its considerable molecular weight and its poor stability [

8].

Previous reviews [

4,

8,

13] have already described that each delivery strategy comprises two key components: the cargo and the vehicle. Cargo refers to what components are delivered inside the cell to enable gene editing and it typically includes CRISPR elements such as plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding Cas9 protein and gRNA; messenger RNA (mRNA) for Cas9 protein translation paired with gRNA; or pre-assembled Cas9/gRNA RNP complexes. Vehicle’s main function is to transport and introduce cargoes into target cells by different methodologies [

8].

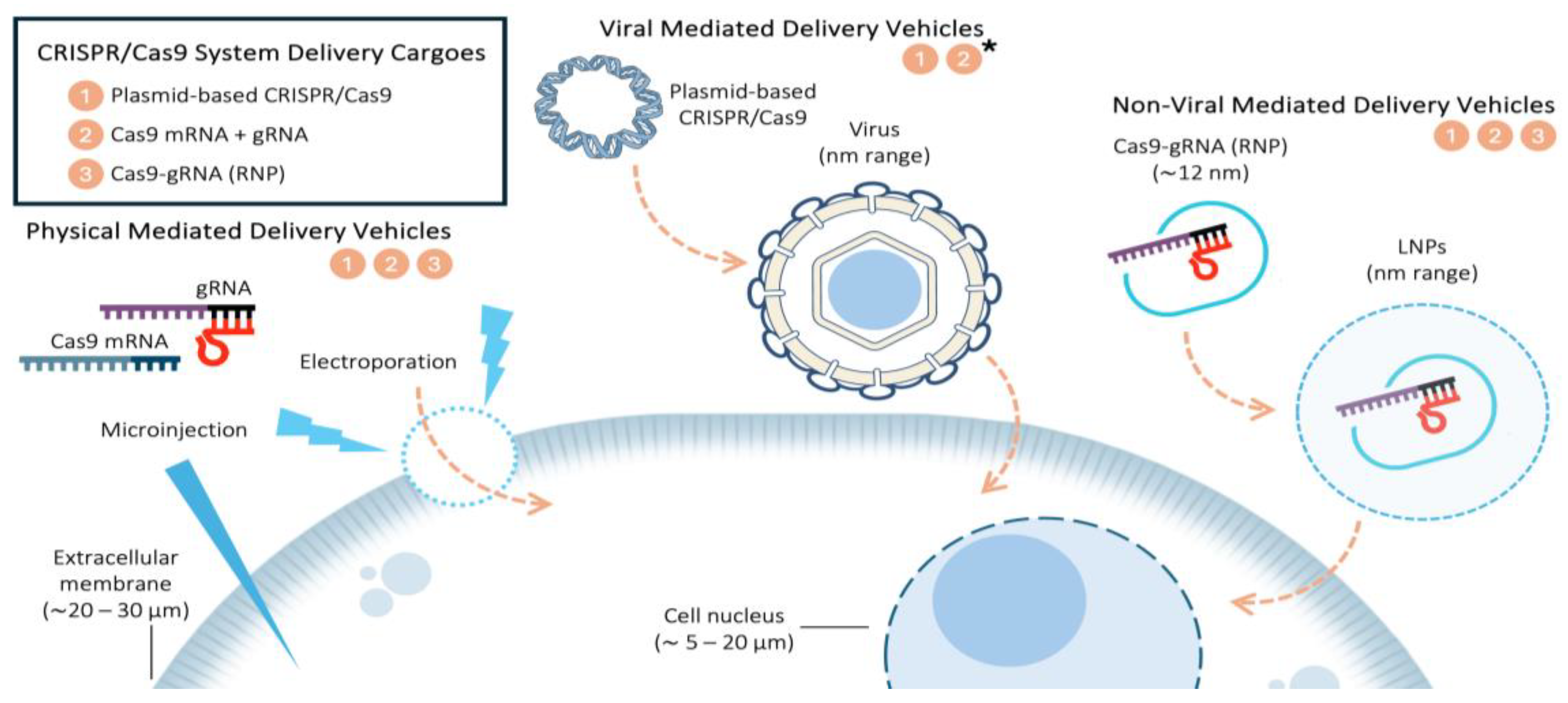

Due to its importance and innumerable applications, recent research has focused on CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems and a classification of both, CRISPR/Cas9 system delivery cargoes and different types of delivery vehicles (

Figure 1) are discussed hereafter, focusing on its strengths, weaknesses and editing efficiency.

2.1. CRISPR/Cas9 System Delivery Cargoes

There are mainly three forms of cargoes in delivery system regarding CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Their associated advantages and drawbacks are discussed subsequently.

Plasmid-based CRISPR/Cas9. This system is widely used due to its simplicity and low cost manipulation [

14]. The moderate toxicity reported in certain cell lines could limit its application as the optimized lipid composition may be different [

15]. In addition, both large Cas9 size and nuclear entry limit its genome editing efficiency [

8,

14]. gRNA can be encoded within the plasmid alongside Cas9 or introduced separately as a synthetic gRNA for more precise control over editing efficiency [

16]. Viral vector cargoes might also included in this category, as they typically deliver DNA or RNA encoding both Cas9 and gRNA, rather than introducing them separately, leading to either, genome integration, transient or episomal expression [

7].

Cas9 mRNA coupled with gRNA. This method offers fast and low toxicity genome editing, making it ideal for sensitive cells. Liu et al. [

17] clearly demonstrated biocompatibility and high genome editing efficacy using bioreducible LNPs by simultaneous delivery of Cas9 mRNA and gRNA. This system decreases off-target editing events, making it suitable for Cas9 transient expression [

14]. The gRNA can either be co-transcribed within the Cas9 mRNA or delivered separately as an independent molecule to optimize stability and efficiency. Viral vectors cargoes could also be in this category when delivering RNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA, without genome integration.

RNP complexes. RNP are composed by Cas9 protein and gRNA, and they offer the highest gene editing efficiency and specificity [

16]. Wei et al. [

18] demonstrated that lipid nanoparticles encapsulating RNP exhibit tissue-specific gene editing in mice lungs and liver. Moreover, this system also minimizes off-target effects and toxicity [

14,

18].

Thus, while the selection of a CRISPR/Cas9 cargo influences gene editing efficiency and specificity, its successful application depends on the appropriate delivery method. Effective genome editing requires not only selecting the most suitable cargo, but also ensuring its efficient transport into target cells (

Figure 1). Each delivery strategy must overcome cellular barriers, optimize uptake, and achieve precise localization to maximize editing efficiency.

Delivery strategies, along with their specific applications and limitations, are discussed in detail in the following sections.

2.2. Types of Delivery Vehicles

There are three primary strategies for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 components into cells (

Figure 1), each influencing genome editing efficiency based on its mechanism of action and delivery vehicles (

Table 1). Physical delivery methods facilitate plasmid transfer, mRNA, or RNP with high efficiency, though, their application may be limited by cell viability and specificity [

17]. Viral vectors vary in the genetic material and they transport either DNA or RNA depending on their genomic structure, influencing whether they mediate transient expression or integrate into the host genome, while also posing size constraints and potential immunogenic risks [

7,

19]. Non-viral systems offer safer alternatives by encapsulating plasmids, mRNA, or pre-formed Cas9:gRNA RNP, though their efficiency relies on uptake mechanisms and overcoming biological barriers [

5,

9,

13,

14,

15]. Since effective encapsulation and delivery depend on electrostatic interactions, the opposite charges on Cas9 (positive) and oligonucleotides or Cas9:gRNA complexes (negative) must be balanced with well-designed carriers. Lipid-based systems, for example, use cationic lipids to form stable lipoplexes that enhance payload protection, cellular uptake, and endosomal escape, ultimately improving genome editing efficiency [

17,

18].

2.2.1. Physical Mediated Delivery Vehicles

Physical delivery methods apply physical forces to facilitate intracellular uptake of CRISPR/Cas9 components by host cellular and nuclear membrane disruption [

5]. Physical methods including microinjection, electroporation, hydrodynamic injection, and sonoporation play a critical role in introducing CRISPR/Cas9 components into cells, offering high precision and versatility across various applications.

Microinjection allows the direct delivery of RNP, plasmid DNA, or mRNA into the cytoplasm or nucleus, making it highly effective for germline editing in model organisms such as zebrafish and mice [

20,

29,

30]. However, its applications in in vivo gene therapy are highly limited because it is labor-intensive, impractical for large-scale systemic administration and highly dependent on the operator. In mammals, microinjection is typically performed in zygotes, requiring the extraction of oocytes, in vitro fertilization, and subsequent embryo implantation. This makes it a feasible approach only for germline editing and not for treating genetic diseases in already born individuals, particularly in adults, where systemic delivery methods are required to reach affected tissues efficiently [

20,

30].

Electroporation, which uses electric fields to create transient pores in cell membrane to uptake macromolecules such as CRISPR/Cas9 components, has demonstrated high transfection efficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), T cells and zygotes among others [

9,

21]. While electroporation is widely used in ex vivo cell therapies, its direct in vivo applications are constrained by potential cellular stress and tissue damage with low efficiency and viability. Moreover, its effects are limited to the electroporated area, making it unsuitable for therapies requiring widespread gene editing across multiple tissues. In addition, it is a costly method, making its clinical applications limited [

19]. However, advances in microscale electroporation systems have improved reproducibility increasing delivery efficiency [

19].

Other physical methods, such as hydrodynamic injection and sonoporation, offer alternative approaches. Hydrodynamic injection involves rapidly injecting large volumes of CRISPR components into bloodstream with high pressure application, achieving high delivery efficiency in mice liver through tail vein injection [

31,

32]. Meanwhile, sonoporation uses low level ultrasound waves to alter the plasma membrane allowing the introduction of editing material into cells, although low gene expression levels is its main drawback [

33].

Despite their advantages, physical methods often face limitations in scalability, tissue specificity and potential cellular damage, therefore several approaches have been developed to enhance CRISPR/Cas9 delivery efficiency and biocompatibility in research and therapeutic studies.

2.2.2. Viral Mediated Delivery Vehicles

Viral engineered vectors such as lentiviruses, adenoviruses (AVs), and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have been extensively used for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 components due to their high transduction efficiency and ability to transfer genetic material into a wide range of cell types [

7,

34,

35,

36,

37]. AAVs, in particular, have become one of the most widely used vectors in gene therapy because of their non-pathogenic nature, and their capacity to transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells with high efficiency [

24,

34,

38]. Lentiviral vectors, by contrast, offer the advantage of stable genome integration, making them highly suitable for ex vivo editing of proliferative cells, such as hematopoietic stem cells [

25,

34,

35]. Depending on the vector type, CRISPR/Cas9 components can be expressed either transiently (as in AAVs or AVs systems) or stabilized through genomic integration (as in lentiviral vectors), with different safety and efficiency implications.

Despite their broad utility, viral vectors present several limitations, where the most relevant is immune response against viral capsid proteins which can reduce transduction efficiency [

39,

40,

41]. Integrating vectors such as lentiviruses and retroviruses also pose risks of off-target genome integration and insertional mutagenesis, potentially leading to genotoxic effects [

35,

39,

42]. Additionally, the limited cargo capacity of AAVs vectors, around 4.7 kb, restricts their use to deliver larger CRISPR/Cas9 systems, especially when including regulatory elements, or several gRNA [

22,

34,

37,

43].

To overcome these challenges, viral vectors have been the focus of extensive studies. In AAVs, capsid modifications have been introduced to improve tissue selectivity and avoid immune detection, while lentiviral vectors have been optimized to enhance nuclear entry and ensure long-term expression in specific cell types [

23,

24,

25,

34]. More recently, alternative viral platforms such as bacteriophage-derived systems have shown promising results improving specificity and reducing immunogenicity, achieving efficiencies comparable to AAVs in certain models [

34,

44]. Viral delivery efficient methods, particularly AAV-based systems, have been demonstrated in preclinical models, showing efficient gene editing in neural tissues of mice (

Table 1) [

22,

45].

While non-viral systems development has opened the scope to safer and more flexible alternatives, viral vectors continue to be the most widely used and clinically validated method for CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. Their unmatched transduction efficiency, versatility, and proven performance in both preclinical and clinical settings underscore their central role in genome editing today, especially in applications where long-term expression or in vivo delivery is essential [

34,

37,

46].

2.2.3. Non-Viral Mediated Delivery Vehicles

Non-viral delivery systems have emerged as a promising alternative to viral vectors, offering increased safety and versatility in delivering CRISPR/Cas9 components. Unlike viral systems, non-viral vehicles pose lower risks of immunogenicity and adverse effects associated with genomic integration [

47].

Among these, LNPs are particularly noteworthy for their ability to encapsulate and protect CRISPR components, enhancing cellular uptake and stability against enzymatic degradation [

17]. LNPs structure and composition facilitates the fusion with cell membrane allowing intracellular CRISPR/Cas9 components delivery to target cells [

48]. LNPs have proven to be especially effective in delivering mRNA and RNP complexes, achieving efficiencies up to 97% in several studies [

5,

12,

26]. Recent innovations in LNPs design have significantly improved their biocompatibility, encapsulation, stability and targeting specificity, binding LNPs with bioreducible lipid-like materials such as cholesterol, 1,2-dioleoyl-

sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine (DOPE), anionic polymers and polyethylene glycol (PEG) derived lipids has demonstrated up to 90% transfection efficiency in vitro or in vivo [

3,

9,

15,

26,

49].

Building on these developments, Guzman Gonzalez et al. [

50] addressed a critical limitation of LNPs for in vivo delivery: their preferential accumulation in hepatic tissues, which restricts their utility for systemic and extrahepatic gene delivery [

50]. An innovative alternative was proposed through the development of cell penetrating peptides capable of stable self-assembling with CRISPR/Cas9 RNA forming Peptide Based Nanoparticles called ADGN. These ADGN peptides are able to self-assemble into stable nanoparticles, encapsulate CRISPR components and efficiently target cells overexpressing laminin receptors, being laminin a characteristic cell surface glycoprotein with increased levels in most cancer cells. Their findings demonstrated significant improvements in cellular uptake, stability, and gene-editing efficiency both in vitro and in vivo

, avoiding preferential accumulation in hepatic tissues and allowing extrahepatic delivery, particularly in lungs mice. This work highlights ADGN potential to broaden the scope of non-viral delivery systems beyond the hepatic scope, opening new avenues for CRISPR-based therapies in oncology and other systemic diseases.

Natural polymer modified carriers, such as chitosan, have also demonstrated significant potential in CRISPR/Cas9 delivery due to their ideal biodegradability, and high biocompatibility. For instance, carboxymethyl chitosan combined with AS1411 ligands achieved over 90% delivery efficiency for plasmid DNA, specifically targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 11 (CDK11) expression in cancer cells [

51]. Similarly, DNA nanoclews, yarn-like DNA nanoparticles synthesized by rolling circle amplification, offer a gene editing approach in in vitro human cells trials [

52]. Moreover, modified polyethylenimine (PEI) polymers have enabled the selective release of CRISPR components, enhancing therapeutic efficacy and safety despite the fact that high molecular weight PEI can induce cytotoxicity [

5,

13,

48].

As an alternative example, hybrid systems combining polymers with inorganic nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles, have further expanded delivery possibilities offering synergistic benefits. Arginine-functionalized gold nanoparticles provide a biocompatible and non-toxic platform for delivery applications [

53]. Moreover, gold nanoparticles have already shown Cas9 and DNA deliver into a wide variety of cell types, and demonstrated as well therapeutic potential by restoring dystrophin expression in mice Duchenne muscular dystrophy [

27]. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) and silica nanoparticles offer additional advantages, providing high-capacity encapsulation and protection of CRISPR components achieving effective gene editing in cancer models [

13,

28,

48,

54].

Emerging technologies continue to address traditional delivery systems limitations by integrating advanced materials and hybrid platforms. Hybridization of exosomes and liposomes demonstrated high specificity and CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid efficient delivery in both in vitro and in vivo assays [

55]. Furthermore, novel developments in gene editing techniques, such as base editing and prime editing, enable specific point mutations without generating double strand DNA breaks, boosting CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutic potential [

34]. Together, these developments underscore the adaptability of polymeric, inorganic, and hybrid delivery systems in overcoming current limitations, thereby improving the safety, efficiency, and specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 based therapies.

3. Aggregation Behavior of Cas9

In the process of the creation of this review, we stumbled upon some information regarding the solubility and aggregation behavior of Cas9. Some authors suggest that buffer composition, pH, and the presence of gRNA significantly influence these processes. Despite this, the extent to which these factors impact gene editing efficiency remains unclear. We hypothesized that Cas9’s aggregation, or the gRNAs, could affect its internalization into cells and delivery systems and ultimately worsen CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing efficiency [

9,

18,

56,

57,

58,

59]. However, there is currently no direct evidence on how aggregation might alter the performance of different delivery methods, making this a critical but unresolved question in the field.

Manzano et al. observed Cas9 aggregation, attributing it to shear-induced processes during stirring, particularly at pH 8 near its isoelectric point [

58]. They determined the effective size of RNP complexes by dynamic light scattering (DLS) in 20 mM Tris and in 300 mM NaCl (pH 8.0), obtaining monodisperse distributions in both conditions with mean diameters of 10.3 ± 1.5 nm and 12.2 ± 1.5 nm, respectively. Nguyen et al. reported a Cas9 size range of 10 – 15 nm in PBS buffer, which aligns with Manzano et al. results [

9]. However, this value increased up to 200 nm upon the addition of gRNA, assuming aggregate formation [

58]. They also noted however that Cas9 is relatively insoluble, and that solubility is increased with gRNA, giving incoherent results. Additionally, Camperi et al., observed small amounts of Cas9 or RNP complexes aggregates and identified different types and levels of aggregation in various sources of gRNA materials by size-exclusion chromatography instead [

59].

We propose to investigate this phenomenon using different techniques, such as DLS, like the one used in the previously mentioned articles; or fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), which has been used to detect and analyze early protein aggregation processes in our group before [

56,

57]. What is more, with these techniques, the size and conformation of the delivery systems, as well as the internalization of the Cas9 or other cargos, can be studied. Understanding these parameters is crucial for optimizing CRISPR-based therapeutic applications, as different aggregation states may affect intracellular processing and activity.

No research has addressed how aggregation affects Cas9 delivery and function, so data is not yet available. Nevertheless, as we will discuss in the next section, there is quantitative evidence on the encapsulation efficiency of Cas9 in different systems, which may offer indirect insights into how aggregation could influence delivery performance. Aggregation could disrupt encapsulation within lipid nanoparticles, or intracellular mobility after electroporation, microinjection or hydrodynamic injection. It could reduce editing efficiency or, unexpectedly, provide stability. It could also impact immune recognition and biodistribution in vivo. Aggregation may alter Cas9 size and structure, affecting its stability, solubility, function and consequently, its delivery. If aggregates are too large, they could hinder cellular uptake and reduce bioavailability. In nanoparticles or polymeric delivery systems, excessive aggregation could reduce encapsulation efficiency. In viral vectors, misfolding could limit the number of active particles. Even inside the cell, aggregation could impair nuclear import and interact with genomic DNA.

To mitigate these challenges, several strategies have been explored to enhance Cas9 and RNA stability and prevent aggregation. Polyglutamic acid coatings have demonstrated the ability to stabilize Cas9 RNP, reducing aggregate formation and improving nanoparticle encapsulation [

9]. Additionally, pre-heating gRNA before complex formation has been shown to improve RNP stability and minimize irreversible aggregation [

59].

4. Encapsulation Efficiency of Cas9

Cas9 delivery remains one of the main challenges in genome editing due to the molecule’s large size and potential instability. While functional outcomes such as gene editing rates are frequently reported, quantitative assessments of Cas9 encapsulation efficiency are less common. Recent studies have focus on the encapsulation performance of different delivery vehicles (

Table 2). Ponomareva et al. clearly showed the low yield of passive loading strategies, with only ~1% of exosome-like vesicles containing detectable Cas9 protein. In contrast, gold nanoparticle based systems demonstrated remarkably precise control over Cas9 loading [

60]. Therefore, Cas9 delivery is essential, but a deeply understanding on how much protein is effectively carried and retained within the carrier is also vital. Moreover, systems such as the one studied by Li et al. based on glycosylated and cascade-responsive nanoparticles, although not providing specific encapsulation ratios, achieved highly efficient functional delivery in glioblastoma models, suggesting optimized loading and release under tumor-specific triggers [

61].

Particle size and homogeneity are extremely related with encapsulation outcomes. Systems with narrow size distributions around 100–200 nm, such as gold-based platforms and optimized LNPs, generally have better intracellular uptake. For instance, Konstantinidou et al. described a system where Cas9 is conjugated to a gold nanoparticle with a hydrodynamic size of ~23 nm allowing nuclear localization and gene-editing activity without transfection reagents [

62]. In contrast, aggregation-prone systems often produce larger and more heterogeneous populations, avoiding endosomal escape and biodistribution. While Manzano et al. reported RNP complex sizes of ~10-12 nm under neutral salt buffers, these expanded to 200 nm upon complexation with gRNA probably due to aggregation [

58]. Such shifts not only alter particle uptake kinetics but also reduce the effective loading capacity per volume and may increase immune recognition. Therefore, delivery systems must be carefully designed to maintain small and stable particle sizes during all stages of storage and administration.

Finally, aggregation can have different approaches. On one hand, too large aggregates for endocytosis reduce cellular internalization and on the other hand, moderate aggregation might enhance local concentration or stability. Nevertheless, most evidence to date suggests aggregation is unfavorable because it decreases encapsulation efficiency, alters particle geometry, and can impair nuclear uptake. For example, electron microscopy of gold nanoparticle conjugated with Cas9 revealed clustered aggregates in some formulations, especially when nitrilotriacetic acid coverage was low [

62]. Strategies such as polyglutamic acid coating, or the use of pre-heated gRNA, have shown promising results reducing aggregation effects [

9,

59]. Crucially, these findings suggest that not just encapsulation amount, but encapsulation quality, including aggregation state and release kinetics, should be optimized to unlock the full potential of Cas9 based therapeutics.

Furthermore, several studies support the strong correlation between encapsulation efficiency and gene editing performance in both in vitro and in vivo systems. Im et al. reported that their LNPs delivering RNP achieved up to 45.2% indel frequency in

IL-10 gene editing, as confirmed by targeted deep sequencing in CT26 tumor cells [

63]. Likewise, studies using virus like particles demonstrated editing rates of 70–90% in human cells and confirmed functional gene knockout in preclinical models [

64].

As previously discussed, systems designed for lung and liver targeting, such as those reported by Wei et al., demonstrated that LNP-mediated delivery of Cas9-RNP enables robust gene editing (

Table 1) with minimal off-target effects [

18]. These findings exemplify the therapeutic relevance of non-viral platforms and help to explain the current shift from viral vectors. Despite their historical predominance due to high transduction efficiency, viral systems such as lentiviruses and AAVs face significant limitations, including immunogenicity, production constraints, and susceptibility to host restriction factors [

37,

40]. Consequently, non-viral strategies like lipid nanoparticles are gaining space as safer and more flexible alternatives for in vivo genome editing.

Table 2.

This table summarizes different Cas9 delivery platforms, focusing on encapsulation efficiency, particle size, and gene editing outcomes. Note that not all studies report precise encapsulation percentages or editing efficiencies in the bibliography.

Table 2.

This table summarizes different Cas9 delivery platforms, focusing on encapsulation efficiency, particle size, and gene editing outcomes. Note that not all studies report precise encapsulation percentages or editing efficiencies in the bibliography.

| Delivery system |

Cas9 encapsulation efficiency |

Particle size (Hydrodynamic) |

Gene editing efficiency/ Therapeutic outcome |

Ref. |

| Exosomes (native) |

~1% (low stochastic loading) |

Not specified |

Poor delivery, not editing data |

[60] |

| Cas9 conjugated to a 12 nm gold nanoparticle |

~45 Cas9 per particle (~6%) |

~23 ± 5 nm |

Comparable to electroporation in reported assays |

[62] |

| LNPs |

Not reported numerically; varied with RNP ratio |

~100-200 nm (est.) |

Up to 45.2% indels in IL-10 gene |

[63] |

| LNPs |

Not quantified |

Not specified |

~3-3.5% HDR integration; 80 % restoration of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel function |

[65] |

| Virus like particles |

Not specified, but functional loading confirmed |

~100-200 nm |

Knockout efficiency 70-90% in vitro and 60-70% in primary human T cells |

[64] |

| Mini enveloped delivery vehicles |

Not quantified |

~120-140 nm (est.) |

Improved gene knockout in human T cells and reduced immunogenic content |

[66] |

| Gold nanoparticle aggregates |

Surface clustering observed (variable density) |

>40nm in aggregated states |

Decreased nuclear entry and editing when aggregation is not controlled |

[62] |

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

CRISPR/Cas9 technique has completely revolutionized genome editing scope since its discovery, providing an accurate and efficient method for DNA modification and opening alternative approaches to numerous illnesses due to its undoubtedly therapeutic potential.

Gene therapy future using CRISPR/Cas9 is based on the development of advanced and specific delivery systems, as well as on improving gene editing precision. Recent advances in nanotechnology, particularly in LNPs use, polymeric carriers, and other non-viral vectors, have significantly enhanced safety and efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems. These systems not only improve cellular uptake but also provide enhanced cargo protection, reducing the risk of off-target effects and enabling tissue specific editing in organs, representing a critical step towards clinical translation [

20,

36].

Moreover, recent evidence has shown that editing outcomes in vivo are closely ralated to the quality of Cas9 encapsulation and its aggregation state. For example, systems achieving over 70% gene knockout in human cells or restoring up to 80% CFTR activity in animal models support the idea that both functional delivery and therapeutic efficiency depend on optimal Cas9 loading and release [

64,

65].

Further investigation will provide new approaches, reducing side effects and improving CRISPR/Cas9 safety. The exploration of novel Cas proteins, such as Cas12, can improve specificity and reduce immunogenicity in genome editing. Therefore, this enzyme can expand gene therapy approaches, providing more precise targeting capabilities and the potential to address a broader range of genetic disorders [

67]. Moreover, optimizing Cas9/gRNA ratio to improve RNP formation may enhance editing efficiency [

68]. In addition, structural studies using techniques like high-speed atomic force microscopy and enhanced molecular simulations have provided deeper insights into Cas9 mechanistic features, clearing the path for highly precise genome editing tools development [

69,

70].

As highlighted in this review, CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems, especially non-viral delivery vehicles including LNPs, have demonstrated promising results improving gene editing safety, efficiency, and specificity. These systems reduce risks associated with viral vectors, such as immunogenicity and off-target genomic integration, while allowing for precise editing in a wide range of tissues. However, Cas9 aggregation could compromise internalization into cells and encapsulation into delivery systems and therefore reduce genome editing efficiency, therefore, a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving aggregation is essential to develop alternative strategies.

Given its potential implications, future research should focus on analyzing Cas9 aggregation across different delivery methods. Techniques such as DLS, FCS, and size-exclusion chromatography could be employed to quantify aggregation levels and evaluate their effects on gene editing efficiency. In addition, considering in vivo applications, it is necessary to explore whether Cas9 aggregates show preferential accumulation in certain tissues or induce unwanted immune reactions. Addressing these questions will be essential to optimize CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies and enhance its therapeutic applications.

In parallel, efforts to correlate encapsulation parameters, such as Cas9 loading per particle or encapsulation efficiency with genome editing performance, will provide a more predictive framework for clinical translation. Quantifying how much Cas9 remains encapsulated, and under which physicochemical conditions delivery improves, should become standard practice in therapeutic development.

Despite technological improvements, ethical concerns surrounding CRISPR/Cas9 application remain present. Germline editing, in particular, raises profound moral and social questions due to its heritable nature, which could lead to unintended long-term implications of genetic modifications. As a result, establishing robust regulatory frameworks is essential to ensure a balance between innovation and safety thus, avoiding potential risks and unintended genomic alterations. Collaborative efforts among scientists, politicians, and society will be critical to establish guidelines that balance innovation with safety.

Ultimately, realizing the full clinical potential of CRISPR requires a multi-perspective approach that addresses technical, ethical, and social challenges, opening the door to safer, more effective, and universally accessible gene editing solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Á.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., D.C. Á.J.A.; writing—review and editing, M.N., W.A.-S., L.S. and Á.J.A.; supervision, M.N., L.S. and Á.J.A.; project administration, M.N., L.S. and Á.J.A.; funding acquisition, M.N., L.S. and Á.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by the collaborative project at Campus Terra, University of Santiago de Compostela, within the framework of the Collaboration Agreement between the USC and the Department of Culture, Education, Vocational Training, and Universities and it was also founded by Fundación Caixa Rural Galega Tomás Notario Vacas within the project Optimizing CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to improve disease resistance in aquaculture. Additionally, this research was carried out under the framework of Spain's Recovery and Resilience Plan, specifically under investment line nº 1 and component number 17, which includes the Complementary RTDI Plan for Marine Science. This plan is part of the Complementary RTDI Plan with the autonomous regions of Spain, including the Marine Science Program for Galicia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A.S. thanks Fundación Caixa Rural Galega Tomás Notario Vacas for his predoctoral contract. D.C. thanks the Xunta de Galicia for his research scholarship “Campus de Especialización Campus Terra”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| Cas9 |

CRISPR-associated 9 |

| gRNA |

Guide RNA |

| RNP |

Ribonucleoprotein |

| LNPs |

Lipid Nanoparticles |

| pDNA |

Plasmid DNA |

| mRNA |

Messenger RNA |

| iPSCs |

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| AVs |

Adenoviruses |

| AAVs |

Adeno-associated viruses |

| DOPE |

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine |

| PEG |

Polyethyleneglycol |

| CDK11 |

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 11 |

| PEI |

Polyethylenimine |

| ZIFs |

Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks |

| DLS |

Dynamic Light Scattering |

| FCS |

Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy |

References

- Sternberg, S.H.; Redding, S.; Jinek, M.; Greene, E.C.; Doudna, J.A. DNA Interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-Guided Endonuclease Cas9. Nature 2014, 507, 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Feng, Q.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, X. Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated Efficient Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for Tumor Therapy. NPG Asia Mater 2017, 9, e441–e441. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 Systems: Delivery Technologies and Biomedical Applications. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 18, 100854. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, F.; Begum, A.A.; Dai, C.C.; Toth, I.; Moyle, P.M. Recent Advances in the Delivery and Applications of Nonviral CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing. Drug Deliv. and Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 1500–1519. [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, P.; Yu, S.-Y.; Thomson, S.B.; Birkenshaw, A.; Leavitt, B.R.; Ross, C.J.D. Lipid-Nanoparticle-Based Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Editing Components. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 19, 1669–1686. [CrossRef]

- Naso, M.F.; Tomkowicz, B.; Perry, W.L.; Strohl, W.R. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 317–334. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Ouyang, K.; Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Wen, C.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z.; Xu, Z.; Sun, W.; Liang, Y. Nanoparticle Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for Genome Editing. Front Genet 2021, 12, 673286. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.N.; Roth, T.L.; Li, P.J.; Chen, P.A.; Apathy, R.; Mamedov, M.R.; Vo, L.T.; Tobin, V.R.; Goodman, D.; Shifrut, E.; et al. Polymer-Stabilized Cas9 Nanoparticles and Modified Repair Templates Increase Genome Editing Efficiency. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- den Engelsman, J.; Garidel, P.; Smulders, R.; Koll, H.; Smith, B.; Bassarab, S.; Seidl, A.; Hainzl, O.; Jiskoot, W. Strategies for the Assessment of Protein Aggregates in Pharmaceutical Biotech Product Development. Pharm Res 2011, 28, 920–933. [CrossRef]

- Pukala, T.L. Mass Spectrometric Insights into Protein Aggregation. Essays Biochem 2023, 67, 243–253. [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.D.; Smith, A.R.; Patel, M.C.; Shaw, L.; Youniss, M.R.; van Heteren, J.; Dirstine, T.; Ciullo, C.; Lescarbeau, R.; Seitzer, J.; et al. A Single Administration of CRISPR/Cas9 Lipid Nanoparticles Achieves Robust and Persistent In Vivo Genome Editing. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 2227–2235. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Gong, C. Nanotechnology-Based CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery System for Genome Editing in Cancer Treatment. MedComm – Biomaterials and Applications 2024, 3, e70. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hu, S.; Chen, X. Non-Viral Delivery Systems for CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing: Challenges and Opportunities. Biomaterials 2018, 171, 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Myhre, J.L.; Chen, S.; Tam, Y.Y.C.; Danescu, A.; Richman, J.M.; Cullis, P.R. Design of Lipid Nanoparticles for in Vitro and in Vivo Delivery of Plasmid DNA. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 1377–1387. [CrossRef]

- Zuris, J.A.; Thompson, D.B.; Shu, Y.; Guilinger, J.P.; Bessen, J.L.; Hu, J.H.; Maeder, M.L.; Joung, J.K.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Liu, D.R. Cationic Lipid-Mediated Delivery of Proteins Enables Efficient Protein-Based Genome Editing in Vitro and in Vivo. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, T.; Mao, L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, M. Fast and Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing In Vivo Enabled by Bioreducible Lipid and Messenger RNA Nanoparticles. Adv Mater 2019, 31, e1902575. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Cheng, Q.; Min, Y.-L.; Olson, E.N.; Siegwart, D.J. Systemic Nanoparticle Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoproteins for Effective Tissue Specific Genome Editing. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3232. [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Morshedi Rad, D.; Mashhadi, S.S.; Ashouri, A.; Mojarrad, M.; Mozaffari-Jovin, S.; Farrokhi, S.; Hashemi, M.; Lotfi, M.; Ebrahimi Warkiani, M.; et al. Recent Advances in CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Approaches for Therapeutic Gene Editing of Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev and Rep 2023, 19, 2576–2596. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiao, Y.; Pan, F.; Guan, Z.; Cheng, S.H.; Sun, D. Knock-In of a Large Reporter Gene via the High-Throughput Microinjection of the CRISPR/Cas9 System. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2022, 69, 2524–2532. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Takemoto, T. Electroporation Enables the Efficient mRNA Delivery into the Mouse Zygotes and Facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 11315. [CrossRef]

- Moffa, J.C.; Bland, I.N.; Tooley, J.R.; Kalyanaraman, V.; Heitmeier, M.; Creed, M.C.; Copits, B.A. Cell Specific Single Viral Vector CRISPR/Cas9 Editing and Genetically Encoded Tool Delivery in the Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.10.10.561249. [CrossRef]

- Waehler, R.; Russell, S.J.; Curiel, D.T. Engineering Targeted Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2007, 8, 573–587. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Samulski, R.J. Engineering Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors for Gene Therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2020, 21, 255–272. [CrossRef]

- Follenzi, A.; Sabatino, G.; Lombardo, A.; Boccaccio, C.; Naldini, L. Efficient Gene Delivery and Targeted Expression to Hepatocytes In Vivo by Improved Lentiviral Vectors. Human Gene Therapy 2002, 13, 243–260. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zuris, J.A.; Meng, F.; Rees, H.; Sun, S.; Deng, P.; Han, Y.; Gao, X.; Pouli, D.; Wu, Q.; et al. Efficient Delivery of Genome-Editing Proteins Using Bioreducible Lipid Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 2868–2873. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Conboy, M.; Park, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Kim, H.J.; Dewitt, M.A.; Mackley, V.A.; Chang, K.; Rao, A.; Skinner, C.; et al. Nanoparticle Delivery of Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein and Donor DNA in Vivo Induces Homology-Directed DNA Repair. Nat Biomed Eng 2017, 1, 889–901. [CrossRef]

- Alsaiari, S.K.; Patil, S.; Alyami, M.; Alamoudi, K.O.; Aleisa, F.A.; Merzaban, J.S.; Li, M.; Khashab, N.M. Endosomal Escape and Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Machinery Enabled by Nanoscale Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 143–146. [CrossRef]

- Averina, O.A.; Permyakov, O.A.; Grigorieva, O.O.; Starshin, A.S.; Mazur, A.M.; Prokhortchouk, E.B.; Dontsova, O.A.; Sergiev, P.V. Comparative Analysis of Genome Editors Efficiency on a Model of Mice Zygotes Microinjection. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10221. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-N.; Fan, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-T.; Chen, S.-Q.; Xie, F.-Y.; Zeng, L.; Wen, J.; Li, J.; Ma, J.-Y.; Ou, X.-H.; et al. High-Survival Rate After Microinjection of Mouse Oocytes and Early Embryos With mRNA by Combining a Tip Pipette and Piezoelectric-Assisted Micromanipulator. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 735971. [CrossRef]

- Niola, F.; Dagnæs-Hansen, F.; Frödin, M. In Vivo Editing of the Adult Mouse Liver Using CRISPR/Cas9 and Hydrodynamic Tail Vein Injection. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1961, 329–341. [CrossRef]

- Kanefuji, T.; Yokoo, T.; Suda, T.; Abe, H.; Kamimura, K.; Liu, D. Hemodynamics of a Hydrodynamic Injection. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development 2014, 1, 14029. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, T.; Huang, L. Nonviral Vectors: We Have Come a Long Way. Adv Genet 2014, 88, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-W.; Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Yi, L.; Lu, J.-C.; Huang, X.-Y.; Cai, J.-B.; Zhang, P.-F.; Cui, Y.-H.; Ke, A.-W. Current Applications and Future Perspective of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Cancer. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 57. [CrossRef]

- Breyer, B.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, H.; Haydon, R.; Zhou, L.; Feng, T.; He, T.-C. Development and Use of Viral Vectors for Gene Transfer: Lessons from Their Applications in Gene Therapy. Viral vectors for gene therapy.

- Walther, W.; Stein, U. Viral Vectors for Gene Transfer. 2000.

- Li, X.; Le, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Nian, X.; Liu, B.; Yang, X. Viral Vector-Based Gene Therapy. IJMS 2023, 24, 7736. [CrossRef]

- Warrington, K.H.; Herzog, R.W. Treatment of Human Disease by Adeno-Associated Viral Gene Transfer. Hum Genet 2006, 119, 571–603. [CrossRef]

- Schauber, C.A.; Tuerk, M.J.; Pacheco, C.D.; Escarpe, P.A.; Veres, G. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Baculovirus Gp64 Efficiently Transduce Mouse Cells in Vivo and Show Tropism Restriction against Hematopoietic Cell Types in Vitro. Gene Ther 2004, 11, 266–275. [CrossRef]

- Coroadinha, A.S. Host Cell Restriction Factors Blocking Efficient Vector Transduction: Challenges in Lentiviral and Adeno-Associated Vector Based Gene Therapies. Cells 2023, 12, 732. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Han, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Von Brunn, A.; Lei, J. Viral Vector-based Cancer Treatment and Current Clinical Applications. MedComm – Oncology 2023, 2, e55. [CrossRef]

- Nasimuzzaman, M. Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Genetic Diseases: Challenges and Prospects. JHVRV 2014, 2. [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.H.; Nakai, H.; Thompson, A.R.; Storm, T.A.; Chiu, W.; Snyder, R.O.; Kay, M.A. Nonrandom Transduction of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors in Mouse Hepatocytes In Vivo: Cell Cycling Does Not Influence Hepatocyte Transduction. J Virol 2000, 74, 3793–3803. [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-Y.; Pan, Y.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-H.; Lim, S.-K.; Cheng, T.-W.; Huang, S.-W.; Wu, S.M.-Y.; Sun, C.-P.; Tao, M.-H.; Mou, K.Y. Improvement of Gene Delivery by Minimal Bacteriophage Particles. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 14532–14544. [CrossRef]

- Bezeljak, U. Cancer Gene Therapy Goes Viral: Viral Vector Platforms Come of Age. Radiology and Oncology 2022, 56, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, A.M.; Porteus, M.H. Answered and Unanswered Questions in Early-Stage Viral Vector Transduction Biology and Innate Primary Cell Toxicity for Ex-Vivo Gene Editing. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 660302. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, M.C.P.; Kont, A.; Kowalski, P.S.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Design of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Delivery of Therapeutic Nucleic Acids. Drug Discovery Today 2023, 28, 103505. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hwang, Y.; Lim, S.; Jang, H.-K.; Kim, H.-O. Advances in Nanoparticles as Non-Viral Vectors for Efficient Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1197. [CrossRef]

- Miteva, M.; Kirkbride, K.C.; Kilchrist, K.V.; Werfel, T.A.; Li, H.; Nelson, C.E.; Gupta, M.K.; Giorgio, T.D.; Duvall, C.L. Tuning PEGylation of Mixed Micelles to Overcome Intracellular and Systemic siRNA Delivery Barriers. Biomaterials 2015, 38, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Guzman Gonzalez, V.; Grunenberger, A.; Nicoud, O.; Czuba, E.; Vollaire, J.; Josserand, V.; Le Guével, X.; Desai, N.; Coll, J.-L.; Divita, G.; et al. Enhanced CRISPR-Cas9 RNA System Delivery Using Cell Penetrating Peptides-Based Nanoparticles for Efficient in Vitro and in Vivo Applications. J Control Release 2024, 376, 1160–1175. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-Y.; He, X.-Y.; Zhuo, R.-X.; Cheng, S.-X. Tumor Targeted Genome Editing Mediated by a Multi-Functional Gene Vector for Regulating Cell Behaviors. Journal of Controlled Release 2018, 291, 90–98. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ji, W.; Hall, J.M.; Hu, Q.; Wang, C.; Beisel, C.L.; Gu, Z. Self-Assembled DNA Nanoclews for the Efficient Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Editing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2015, 54, 12029–12033. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-C.; Samanta, B.; Agasti, S.S.; Jeong, Y.; Zhu, Z.-J.; Rana, S.; Miranda, O.R.; Rotello, V.M. Drug Delivery Using Nanoparticle-Stabilized Nanocapsules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2011, 50, 477–481. [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.Z.; Alsaiari, S.K.; Li, Y.; Qutub, S.S.; Aleisa, F.A.; Sougrat, R.; Merzaban, J.S.; Khashab, N.M. Cell-Type-Specific CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery by Biomimetic Metal Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1715–1720. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Iqbal, Z.; Ouyang, K.; Zhang, H.; Wen, C.; Duan, L.; Xia, J. Chondrocyte-Specific Genomic Editing Enabled by Hybrid Exosomes for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4866–4878. [CrossRef]

- Novo, M.; Pérez-González, C.; Freire, S.; Al-Soufi, W. Early Aggregation of Amyloid-β(1–42) Studied by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. In Protein Aggregation; Cieplak, A.S., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer US: New York, NY, 2023; Vol. 2551, pp. 1–14 ISBN 978-1-07-162596-5.

- Novo, M.; Freire, S.; Al-Soufi, W. Critical Aggregation Concentration for the Formation of Early Amyloid-β (1-42) Oligomers. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1783. [CrossRef]

- Manzano, I.; Taylor, N.; Csordas, M.; Vezeau, G.E.; Salis, H.M.; Zydney, A.L. Purification of Cas9—RNA Complexes by Ultrafiltration. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37. [CrossRef]

- Camperi, J.; Moshref, M.; Dai, L.; Lee, H.Y. Physicochemical and Functional Characterization of Differential CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 1432–1440. [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, N.I.; Brezgin, S.A.; Kostyusheva, A.P.; Slatinskaya, O.V.; Bayurova, E.O.; Gordeychuk, I.V.; Maksimov, G.V.; Sokolova, D.V.; Babaeva, G.; Khan, I.I.; et al. Stochastic Packaging of Cas Proteins into Exosomes. Mol Biol 2024, 58, 147–156. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Cascade-Responsive Nanoparticles for Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-Based Glioblastoma Gene Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 4480–4489. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidou, S.; Lindstaedt, A.; Schmidt, T.J.N.; Nocilla, F.; Maltinti, G.; Rocco, M.A.; Landi, E.; Carli, A.D.; Crucitta, S.; Lai, M.; et al. A Transfection-Free Approach of Gene Editing via a Gold-Based Nanoformulation of the Cas9 Protein 2024.

- Im, S.H.; Jang, M.; Park, J.-H.; Chung, H.J. Finely Tuned Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles for CRISPR/Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Delivery and Gene Editing. J Nanobiotechnol 2024, 22, 175. [CrossRef]

- Borovikova, S.E.; Shepelev, M.V.; Mazurov, D.V.; Kruglova, N.A. Efficient Genome Editing Using ‘NanoMEDIC’ AsCas12a-VLPs Produced with Pol II-Transcribed crRNA. IJMS 2024, 25, 12768. [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.A.; Ayoub, P.G.; Sinha, V.; Juett, C.; Sanoyca, A.; Duggan, E.C.; Lathrop, L.E.; Bhatt, P.; Coote, K.; Illek, B.; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles for the Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Machinery to Enable Site-Specific Integration of CFTR and Mutation-Agnostic Disease Rescue 2025.

- Ngo, W.; Peukes, J.T.; Baldwin, A.; Xue, Z.W.; Hwang, S.; Stickels, R.R.; Lin, Z.; Satpathy, A.T.; Wells, J.A.; Schekman, R.; et al. Mechanism-Guided Engineering of a Minimal Biological Particle for Genome Editing.

- Schubert, M.S.; Thommandru, B.; Woodley, J.; Turk, R.; Yan, S.; Kurgan, G.; McNeill, M.S.; Rettig, G.R. Optimized Design Parameters for CRISPR Cas9 and Cas12a Homology-Directed Repair. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 19482. [CrossRef]

- Chenouard, V.; Leray, I.; Tesson, L.; Remy, S.; Allan, A.; Archer, D.; Caulder, A.; Fortun, A.; Bernardeau, K.; Cherifi, Y.; et al. Excess of Guide RNA Reduces Knockin Efficiency and Drastically Increases On-Target Large Deletions. iScience 2023, 26, 106399. [CrossRef]

- Palermo, G.; Miao, Y.; Walker, R.C.; Jinek, M.; McCammon, J.A. CRISPR-Cas9 Conformational Activation as Elucidated from Enhanced Molecular Simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 7260–7265. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Nishimasu, H.; Kodera, N.; Hirano, S.; Ando, T.; Uchihashi, T.; Nureki, O. Real-Space and Real-Time Dynamics of CRISPR-Cas9 Visualized by High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1430. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).