Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Selection

2.2. Samples

2.3. DNA-Extraction

2.4. Molecular Methods

2.5. Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CLIA)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, S.; Lavergne, V.; Skinner, AM.; Gonzales-Luna, A. J.; Garey, K. W.; Kelly, C. P.; Wilcox M., H. Clinical Practice Guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 Focused Update Guidelines on Management of Clostridioides difficile Infection in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 5, e1029–e1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, G. L.; Bourgault, A.; Poirier, L.; Lamothe, F.; Michaud, S.; Turgeon, N.; Toye, B.; Beaudoin, A.; Frost, E.H.; Gilca, R.; et al. Host and Pathogen Factors for Clostridium difficile Infection and Colonization. N Engl J Med. 2011, 18, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja-Sierra, T. Diarrea asociada a Clostridium difficile en el anciano: nuevas perspectivas. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. 2015, 4, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneur, O.; Ottone, S.; Delauzun, V.; Bastide, M.-C.; Foussadier, A. Molecular cloning, overexpression in Escherichia coli, and purification of 6x his-tagged C-terminal domain of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Protein Expr Purif. 2003, 31, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, E.J.; Tiruvoipati, R. Management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults and challenges in clinical practice: review and comparison of current IDSA/SHEA, ESCMID and ASID guidelines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022, 78, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carey-Ann, B.D.; Carroll, K.C. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile Infection: an Ongoing Conundrum for Clinicians and for Clinical Laboratories. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013, 26, 604–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutanen, S.M.; Simor, A.E. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004, 171, 51–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crobach, M.T.; Vernon, J.J.; Loo, V.G.; Kong, L.Y.; Péchiné, S.; Wilcox, M.H.; Kuijper, E.J. Understanding Clostridium difficile Colonization. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018, 31, e00021-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- CDC. Clinical Guidance for C. diff Prevention in Acute Care Facilities. March 8, 2024.

- McDonald, L. C.; Gerding, D. N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J. S.; Carroll, K. C.; Coffin, S. E.; Dubberke, E. R.; Garey, K. W.; Gould, C. V.; Kelly, C. et. al. , Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 7, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Lemée, L.; Monnier, A.; Poilane, I.; Pons, J. L.; Collignon, A. Prevalence and diversity of Clostridium difficile strains in infants. J Med Microbiol. 2011, 60, 1112–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutova, M.; de Meij, T. J.; Fitzpatrick, F.; Drew, R. J.; Wilcox, M. H.; Kuijper, E. J. How to: Clostridioides difficile infection in children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022, 8, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, C. H.; Pickering, D. S.; Freeman, J. Microbiologic factors affecting Clostridium difficile recurrence. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018, 24, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A. E.; Theriot, C. M.; Bergin, I. L.; Huffnagle, G. B.; Schloss, P. D.; Young, V. B. The interplay between microbiome dynamics and pathogen dynamics in a murine model of Clostridium difficile Infection. Gut Microbe. 2011, 2, 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumpitazi, B. P,.; Self, M. M.; Czyzewski, D. I., Cejka, S.; Swank, P. R.; Shulman, R. J. Bristol Stool Form Scale reliability and agreement decreases when determining Rome III stool form designations. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016, 3, 443–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janczura, A.; Smutnicka, D.; Junka, A.; Gościniak, G. The detection and expression of enterotoxinencoding lth gene among Klebsiella spp. isolated from diarrhea. Central European Journal of Biology. 2013, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prehn, J.; Reigadas, E.; Vogelzang, E.; Bouza, E.; Hristea, A.; Guery, B.; Krutova, M.; Norén, T.; Allerberger, F.; Coia, J.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 update on the treatment guidance document for Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, S.; Ascenzi, P.; Siarakas, S.; Petrosillo, N.; Di Masi, A. Clostridium difficile Toxins A and B: Insights into Pathogenic Properties and Extraintestinal Effects. Toxins 2016, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva E., G.; Ivanov I., N.; Vathcheva-Dobrevska, R. S.; Ivanova, K. I.; Asseva, K.; Petrov, P. K.; Kantardjiev, T. V. ; Advances in molecular surveillance of Clostridium difficile in Bulgaria. J Med Microbiol. 2013, 62, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobreva, Е.; Ivanov I., N.; Vatcheva-Dobrevska, R.; Ivanova, K.; Marina, M.; Petrov, P.; Kantardjiev, T.; Kuijper, E. Toxin encoding genes characterization of Bulgarian Clostridium difficile clinical strains. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2012, 65, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Forward, L. J.; Tompkins, D. S.; Brett, M. M. Detection of Clostridium difficile cytotoxin and Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin in cases of diarrhoea in the community. J Med Microbiol. 2003, 52, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, Y.; Lee, S.W.; Cho, H. H.; Park, S.; Chung, H. S.; Seo, J. W. Antibiotics-Associated Hemorrhagic Colitis Caused by Klebsiella oxytoca: Two Case Reports. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2018, 2, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Selvaraj, V.; Alsamman, M. A. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea Beyond C. Difficile: A Scoping Review. Brown Hospital Medicine 2022, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanafer, N.; Vanhems, P.; Bennia, S.; Martin-Gaujard, G.; Juillard, L.; Rimmelé, T.; Argaud, L.; Martin, O.; Huriaux, L.; Marcotte, G.; et., al. Factors Associated with Clostridioides (Clostridium) Difficile Infection and Colonization: Ongoing Prospective Cohort Study in a French University Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

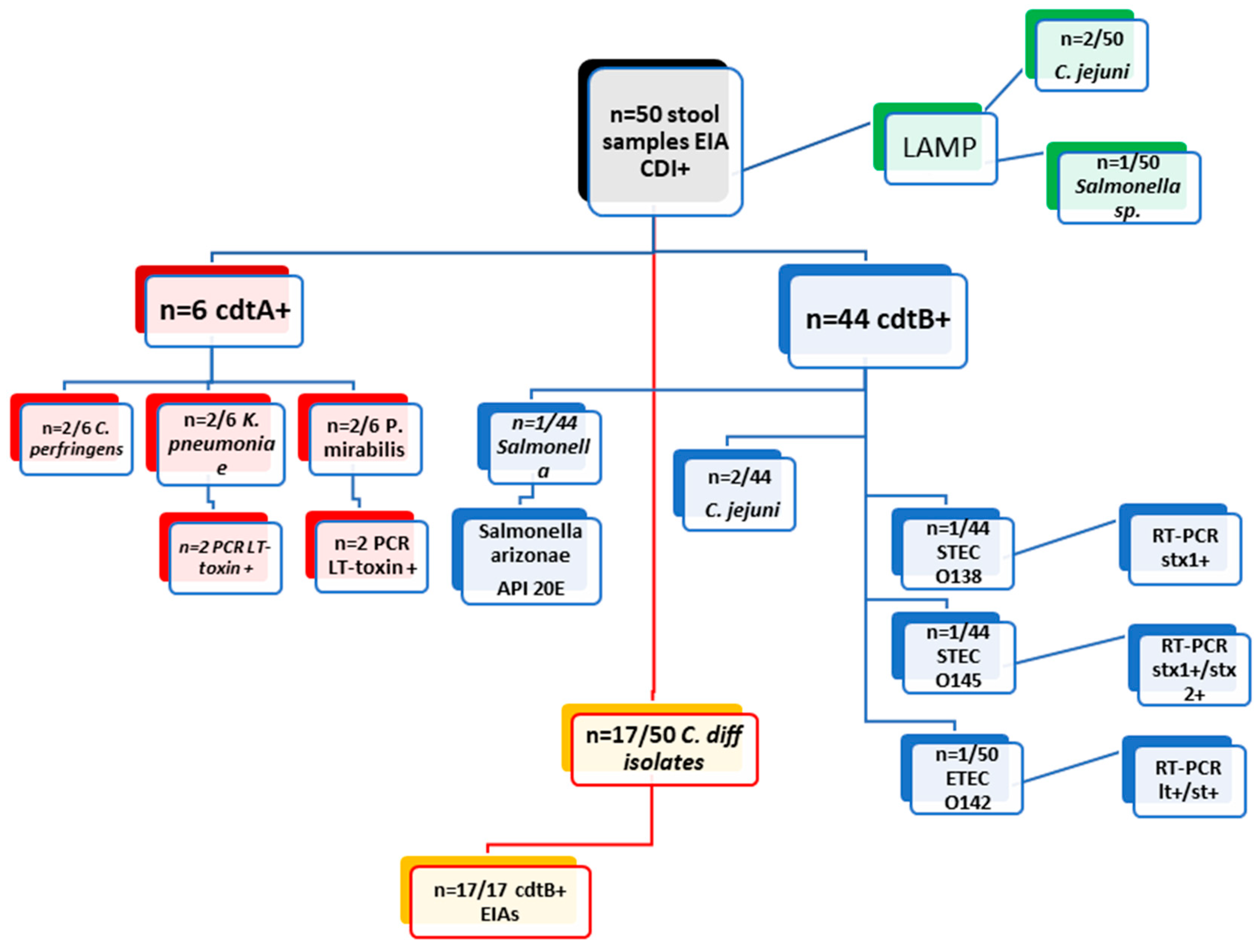

| Examination of 50 clinical stool samples cdtA+/cdtB+ by EIAs from DT-hospital | |||||||||

| methods | EIA cdtA + ( n= 6/50) | EIA cdtB + ( n= 44/50) | |||||||

| culture | C. perfringens (2/6) | K. pneumoniae (2/6) | P. Mirabilis (2/6) | Salmonella | C. difficile (17/44) | C. jejuni (2/44) | STEC O138 (1/44) | STEC O145 (n=1) | ETEC 142 (1/44) |

| PCR | x | LT toxin (n=2) | LT toxin (n=2) | x | x | x | stx1+ (n=1) | stx1+/stx2+ (n=1) | lt+/st+ (n=1) |

| API20E | x | x | x | Salmonella arizonae | x | x | x | x | x |

| LAMP (Salmonella/ Campylobacter) | negative | negative | negative | Salmonella | negative | C. jejuni (2/44) | negative | negative | negative |

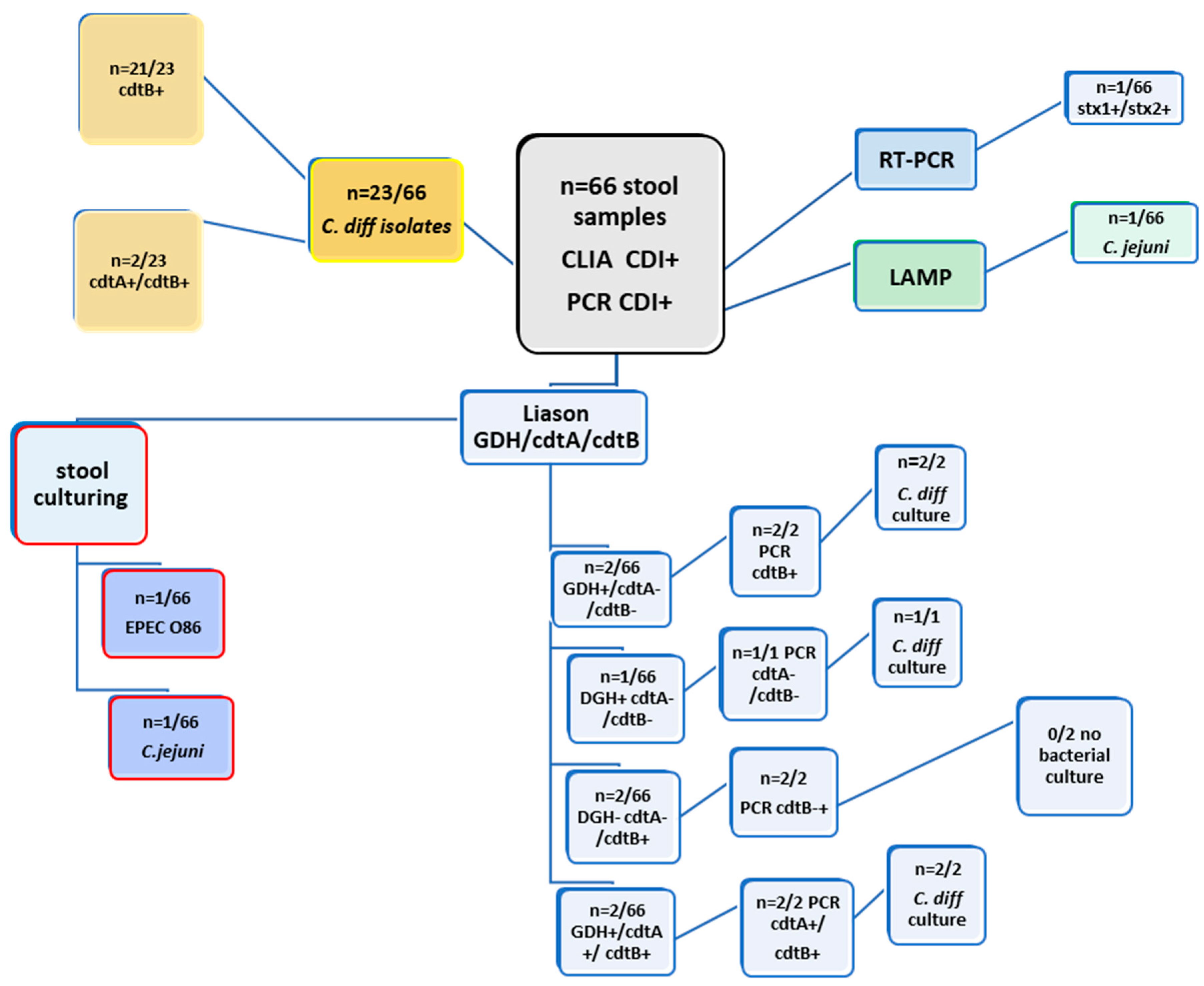

| Examination of 66 clinical stool samples by CLIA (GDH; cdtA/B) and PCR (cdtA; cdtB) from SF-hospital | ||||||||

| METHODS | Liason GDH | Liason cdtA | Liason cdtB | PCR cdtA | PCR cdtB | culture | LAMP | RT-PCR (STEC) |

| 2/66 | negative | negative | negative | 2/66 | C. difficile (n=2/66) | negative | x | |

| 1/66 | negative | negative | negative | negative | C.difficile(n=1/66) | negative | x | |

| negative | negative | 2/66 | negative | 2/66 | negative | negative | x | |

| negative | negative | 1/66 | negative | 1/66 | C.jejuni(n=1/66) | C.jejuni | x | |

| negative | negative | 1/66 | negative | 1/66 | EPEC O86 | negative | stx1+/stx2+ | |

| 2/66 | 2/66 | 2/66 | 2/66 | 2/66 | 2/66 | negative | x | |

| negative | negative | 21/23 | negative | 21/23 | C. difficile (n=23/66) | negative | x | |

| negative | 2/23 | 2/23 | negative | 2/23 | C.difficile (n=23/66) | negative | x | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).