1. Introduction

Clostridioides difficile (CD) is a spore-forming, anaerobic, gram-positive bacteria. CD infection (CDI), the most common cause of healthcare-associated infection (HCA) [

1] is an ongoing major global public health concern, and typically occurs after antibiotic use disrupts the normal gut microbiota. Despite recent downward trends in HCA-CDI, CDI is considered an urgent threat causing 235,700 cases in hospitalized patients and 16,200 deaths and an estimated

$1 billion in healthcare costs annually [

2,

3]. Incidence of CDI increased during the 2000’s coincident with the spread of a novel hypervirulent strain, designated PCR ribotype (RT) 027, North American Pulse Field 1 (NAP1), or restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) type BI. Despite effective treatment of the initial infection, 15-35% of CDI cases spontaneously recur after cessation of initial therapy [

4,

5].

The Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (HVAH) participates in the VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) trial, CSP #596: “Optimal Treatment of Recurrent C. difficile Infection (OpTION).” As part of this study pre-screening data are collected on all HVAH patients with positive CD stool test results and/or who are treated for CDI. Patient records are tracked to identify cases of recurrent CDI (rCDI) within 90 days after successful treatment.

The rapid global spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) resulted in the declaration of a national emergency in the United States and nationwide shutdowns on March 13, 2020. These pandemic shutdowns markedly altered hospitalizations even for non-COVID-19 patients. In order to study the interaction of COVID-19 and CDI, we examined rates of CDI, rCDI, and CD stool testing in 2020 and 2021 at our hospital in comparison to prior years. We also performed REA strain typing on stool samples collected prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Results

2.1. CD Stool Testing

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic from January 1, 2015 – December 31, 2019 a mean of 15.12 (95% CI: 14.20 – 16.03) CDI cases/month were diagnosed and/or treated at HVAH (

Table 1). During this time a mean of 15.45 submitted stool tests were positive for CD by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) monthly (95% CI: 14.53 – 16.37). Annually, a mean of 140.0 unique patients had NAAT+ stool test results in 2015 – 2019 (n=700) and a mean of 136.0 unique patients were treated for CDI during this time (n=680). Beginning in early 2020 and continuing throughout 2021 there was a significant 35.3% decline in monthly NAAT+ stool tests to a mean of 10.00 (95% CI: 8.94 – 11.06; P<0.01). This reduction in monthly NAAT+ stool tests remained consistent in both pandemic years with a mean of 9.33 (95% CI: 7.79 – 10.87; P<0.01) monthly NAAT+ tests in 2020 and a mean of 10.67 (95% CI: 9.06 – 12.28; P<0.01) monthly NAAT+ tests in 2021.

The number of monthly CDI diagnoses also declined significantly across 2020 – 2021 to a mean of 8.58 (95% CI: 7.68 – 9.49; P<0.01), representing a 43.2% fall in monthly CDI cases compared to the prior 5 years. Monthly CDI diagnosis was also consistently lower in both 2020 (8.17 CDI diagnoses/month (95% CI: 6.90 – 9.43; P<0.01) and 2021 (9.00 CDI diagnoses/month (95% CI: 7.54 – 10.46; P<0.01). The mean annual numbers of unique patients with NAAT+ stool testing (92.0; n=184) and mean annual unique CDI patients (75.0; n=150) were also lower in 2020 – 2021 compared to the prior 5 years.

The mean monthly number of rCDI cases was also significantly lower in 2020 – 2021 [1.92 (95% CI: 1.27 – 2.56) vs. 3.38 (95% CI: 2.89 – 3.87); P<0.01], representing a 43.4% decrease in monthly CDI recurrence. In the 5 years preceding the pandemic a total of 203 recurrences were documented among 907 CDI cases (22.4%) within 3 months. The rate of CDI recurrence was similar overall in 2020 – 2021 (46 recurrences out of 206 CDI cases; 22.3%). However a lower percentage of CDI cases recurred in the first year of the pandemic (15 recurrences out of 98 CDI cases; 15.3%) while the rate of CDI recurrence increased in 2021 (31 recurrences out of 108 CDI cases; 28.7%. The mean monthly number of CDI recurrences was significantly lower in 2020 (1.25; 95% CI: 0.53 – 1.97; P<0.01), but not in 2021 (2.58; 95% CI: 1.55 – 3.61; P=0.18).

Comparison of total CD positivity rate (fraction of all stool tests that were CD+ by NAAT) revealed a significant decline from a mean of 17.2% positivity in 2018 and 2019 (393 NAAT+ of 2287 tests run) to 14.3% positivity during 2020 – 2021 (240 NAAT+ of 1681 tests run; P = 0.01). CD positivity rate was lower in both 2020 (112 NAAT+ of 789 tests run; 14.2%; P=0.05) and in 2021 (128 NAAT+ of 892 tests run; 14.4%; P=0.05). Data for 2015 – 2017 were unavailable for comparison. Throughout the analysis period there was no change in the small percentage of cases that were treated for CDI without confirmatory stool testing.

Table 1.

Total CD Stool Testing at HVAH from 2015 - 2021.

Table 1.

Total CD Stool Testing at HVAH from 2015 - 2021.

| |

Pre-Pandemic (2015-2019) |

First Pandemic Year (2020) |

P-value*

|

Second Pandemic Year (2021) |

P-value†

|

Pandemic Years (2020-2021) |

P-value‡

|

| Mean Monthly NAAT1+ Tests (95% CI; n) |

15.45 (14.53 – 16.37; n=927) |

9.33 (7.79 – 10.87; n=112) |

<0.01 |

10.67 (9.06 – 12.28; n=128) |

<0.01 |

10.00 (8.94 – 11.06; n=240) |

<0.01 |

| Mean Monthly Total CDI2 Cases (95% CI; n) |

15.12 (14.20 – 16.03; n=907) |

8.17 (6.90 – 9.43; n=98) |

<0.01 |

9.00 (7.54 – 10.46; n=108) |

<0.01 |

8.58 (7.68 – 9.49; n=206) |

<0.01 |

| Mean Monthly rCDI3 Cases (95% CI; n) |

3.38 (2.89 – 3.87; n=203) |

1.25 (0.53 – 1.97; n=15) |

<0.01 |

2.58 (1.55 – 3.61; n=31) |

0.18 |

1.92 (1.27 – 2.56; n=46) |

<0.01 |

| No. Total NAAT+ CD4 Stool Tests in 2018-2021 (Total Stool Tests Run; %NAAT+) |

393 (2287; 17.2%) |

112 (789; 14.2%) |

0.05 |

128 (892; 14.4%) |

0.05 |

240 (1681; 14.3%) |

0.01 |

| Mean Monthly CD Colonization (95% CI; n) |

0.33 (0.15 – 0.52; n=20) |

1.17 (0.51 – 1.82; n=14) |

<0.01 |

1.67 (0.98 – 2.35; n=20) |

<0.01 |

1.42 (0.97 – 1.86; n=34) |

<0.01 |

1NAAT: Nucleic acid amplification test; 2CDI CD Infection;; 3rCDI: recurrent CDI; 4CD: Clostridioides difficile.

*Comparing 2020 vs. 2015 – 2019; †Comparing 2021 vs. 2015 – 2019; ‡Comparing 2020 – 2021 vs. 2015 – 2019. |

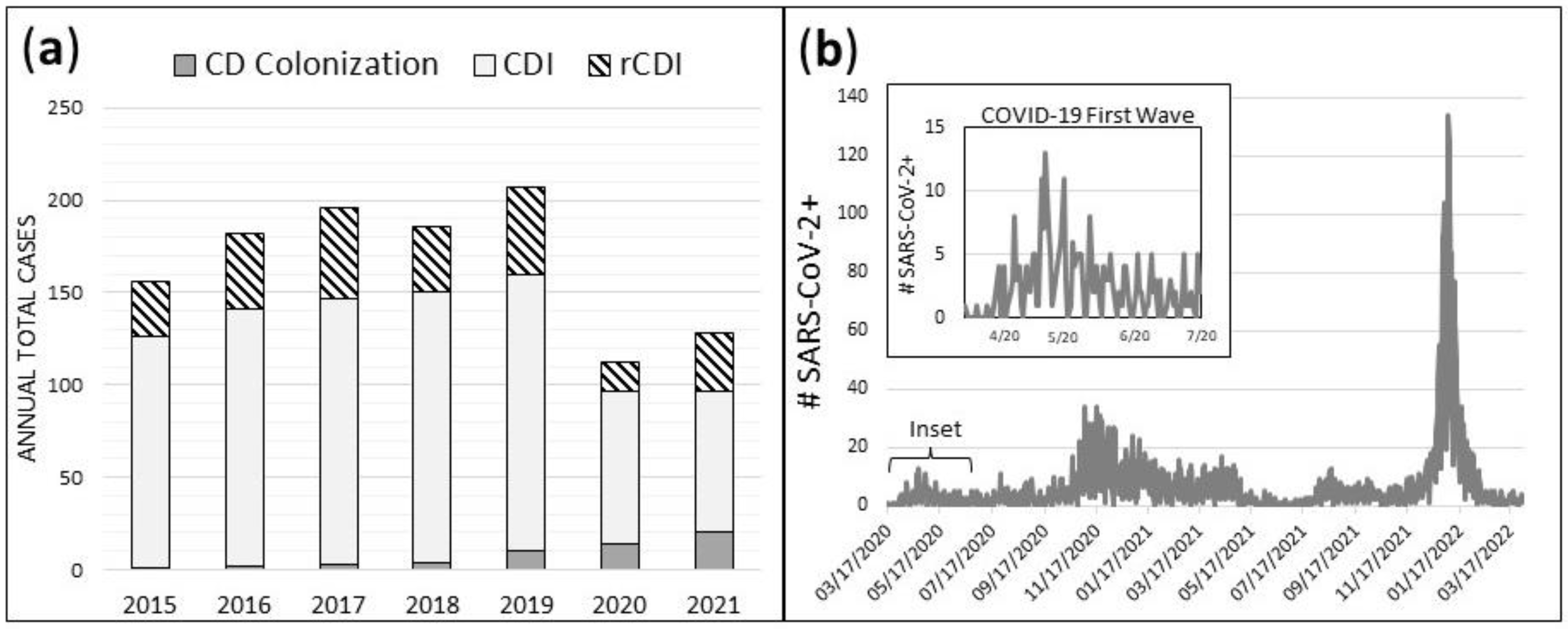

Prior to implementation of reflex enzyme immunosorbent assay (EIA) toxin stool testing in September of 2019, CD colonization was diagnosed rarely, and most NAAT+ patients were treated for CDI. After implementation of stool toxin testing which was perfomed following a NAAT+ stool test, CD colonization was more frequently diagnosed when toxin testing was negative coupled with a documented lack of ongoing diarrhea and/or presence of an identifiable alternative source of diarrhea. From 2015 – 2019, a mean of 0.33 cases/month (95% CI: 0.15 – 0.52) were diagnosed as CD colonization and were thus not treated for CDI (

Table 1). After implementation of the 2-step reflex to EIA toxin testing algorithm in September 2019, monthly CD colonization diagnoses increased more than 4-fold in 2020 – 2021 to 1.42 cases/month (95% CI: 0.97 – 1.86); P < 0.01). Monthly CD colonization diagnosis was significantly higher in both 2020 (1.17; 95% CI: 0.51 – 1.82; P<0.01) and in 2021 (1.67; 95% CI: 0.98 – 2.35; P<0.01). Throughout our study period CDI diagnosis was defined as a case that required medical treatment for CD infection regardless of toxin positivity status. While increased CD colonization diagnosis in 2020 – 2021 reduced the proportion of all NAAT+ cases that were treated for CDI, it did not account for the overall reduction in NAAT+ stool testing, CDI, and rCDI during this time period. Our hospital documented a total of only 112 NAAT+ stool tests in 2020, and 128 NAAT+ stool tests in 2021 compared to a mean of 185.4 NAAT+ stool tests/year over the prior 5 years (

Figure 1a). Daily case count of SARS-CoV-2+ patients at HVAH from March 17, 2020 – March 31, 2022 is shown for comparison (

Figure 1b). Daily case count of SARS-CoV-2+ patients at HVAH during the first pandemic wave from March 17, 2020 – June 30, 2020 are shown in

Figure 1b (inset).

Figure 1.

Total annual cases of CD colonization, CDI, and rCDI (a), and daily case count of SARS-CoV-2+ patients at HVAH from March 17, 2020 – March 31, 2022 (b).

Figure 1.

Total annual cases of CD colonization, CDI, and rCDI (a), and daily case count of SARS-CoV-2+ patients at HVAH from March 17, 2020 – March 31, 2022 (b).

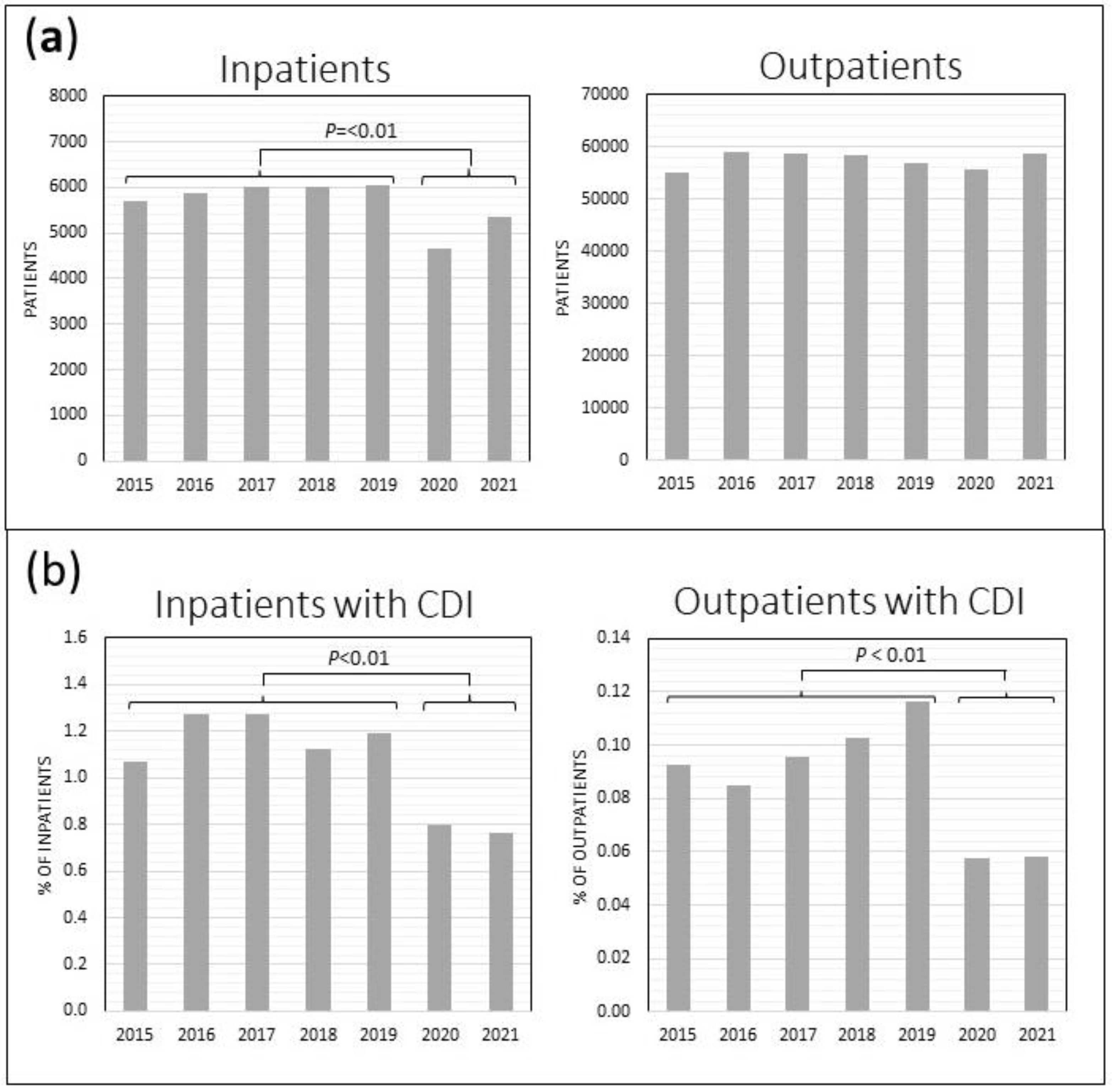

Overall annual HVAH patient volume decreased during the pandemic years. There was a 15.6% decline in unique inpatient admissions in 2020 – 2021 compared to the prior 5 years (5009/year vs. 5933/year; P<0.01), while the outpatient volume remained unchanged (57,597 vs. 57,102 unique outpatients/year,

Figure 2a

). However, there was a significant 34.2% decline in the frequency of CDI diagnosis among inpatients in 2020 – 2021 (0.78% vs 1.19% of inpatient admissions, P<0.01) as well as a 41.2% decline in CDI diagnosis among unique outpatients per year (0.058% vs 0.098%, P<0.01) in 2020 – 2021 compared to the prior 5 years (

Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

HVAH inpatient and outpatient census (a), and rate of CDI diagnosis among inpatients and outpatients (b). Inpatients include those in the acute care wards and the contiguous extended care facility.

Figure 2.

HVAH inpatient and outpatient census (a), and rate of CDI diagnosis among inpatients and outpatients (b). Inpatients include those in the acute care wards and the contiguous extended care facility.

The majority of CDI diagnoses were among hospital inpatients, and there were no changes in the relative frequency of inpatient diagnosis (69%) compared to outpatient diagnosis (31%) during the period of our analysis. The relative rates of healthcare-onset (HO)-CDI (40%), community-onset (CO)-CDI (47%) and community-onset, health care facility associated (CO-HCFA) CDI (13%) also remained constant from 2015 – 2021.

2.2. REA Typing and Patient Characteristics.

We compared mean patient age, white blood cell count (WBC), serum creatinine, serum albumin, and body temperature on the day of NAAT+ CD stool testing for all patients at HVAC from October 1, 2019 – March 31, 2022 (

Table 2). During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (

Figure 1b) there was a significant increase in mean body temperature compared to the period prior to the COVID-19 lockdown (99.1F vs. 98.2F;

P<0.01). There were no significant changes in mean patient age, serum creatinine, or serum albumin during the study period. Results were similar when only patients with active CDI were considered by excluding patients with CD colonization from the analysis (data not shown).

Table 2.

CD Strain REA Typing, CDI Outcome and Case Characteristics.

Table 2.

CD Strain REA Typing, CDI Outcome and Case Characteristics.

| |

All Encounters |

Pre-Pandemic

(10/1/19 - 3/7/20) |

Initial Pandemic Wave

(3/8/20 - 6/30/20) |

Post - Initial Wave

(7/1/20 - 3/31/22) |

P-value |

| Case Characteristics |

(n=327) |

(n=82) |

(n=32) |

(n=213) |

|

| Median Age (IQR1) |

73 (67 – 78) |

73.0 (67 – 82) |

73.0 (68 – 82) |

73.0 (67 – 77) |

0.96*

|

| No. Male (%) |

316 (96.6) |

77 (93.9) |

31 (96.9) |

208 (97.7) |

0.28†

|

| No. Immunocompromised (%) |

63 (19.3) |

9 (11.0) |

7 (21.9) |

47 (22.2) |

0.09†

|

| No. PPI2 (%) |

192 (58.9) |

45 (55.0) |

19 (59.4) |

128 (60.4) |

0.69†

|

| Mean Temperature, F (95% CI) |

98.2 (98.0 – 98.3) |

98.2 (97.9 – 98.6) |

99.1 (98.4 – 99.8) |

98.0 (97.8 – 98.1) |

<0.01‡

|

| Mean WBC3 (95% CI) |

10.5 (9.8 – 11.2) |

11.3 (9.7 – 12.8) |

8.7 (7.3 – 10.0) |

10.5 (9.6 – 11.4) |

0.17‡

|

| Mean Creatinine (95% CI) |

2.0 (1.8 – 2.3) |

1.7 (1.4 – 2.0) |

1.4 (1.1 – 1.8) |

2.3 (1.9 – 2.6) |

0.05‡

|

| Mean Albumin (95% CI) |

2.6 (2.5 – 2.7) |

2.4 (2.2 – 2.6) |

2.7 (2.5 – 2.9) |

2.6 (2.5 – 2.8) |

0.14‡

|

| REA4 Strain Typing |

(n=159) |

(n=44) |

(n=15) |

(n=100) |

|

| No. REA Group Y (RT 014/020) (%) |

32 (20.1) |

12 (27.3) |

1 (6.7) |

19 (19.0) |

0.21†

|

| No. REA Group BI (RT 027) (%) |

19 (12.0) |

4 (9.1) |

4 (26.7) |

11 (11.0) |

0.17†

|

| No. REA Group DH (RT 106) (%) |

20 (12.6) |

3 (6.8) |

2 (13.3) |

15 (15.0) |

0.39†

|

| Other REA Groups (%) |

88 (55.4) |

25 (56.8) |

8 (53.3) |

55 (55.0) |

0.97†

|

*Kruskal-Wallis test comparing differences across three time periods; †Chi-square analysis comparing differences across three time periods; ‡One-way ANOVA analysis comparing differences across three time periods.

1IQR: Interquartile range; 2PPI: Proton pump inhibitors; 3WBC: White blood cell count; 4REA: Restriction endonuclease analysis; 5RT: PCR ribotype. |

We performed REA typing of stool samples collected between October 1, 2019 and March 31, 2022. Prior to March 8, 2020 REA group Y was the most prevalent CD strain, accounting for 27.3% of isolates (n=12;

Table 2). During the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 8, 2020 – June 30, 2020) there was an increase in the prevalence of REA strain type BI (26.7% vs. 9.1%;

P=0.17). Although the small number of BI infections did not contribute to an overall increase in CDI recurrence or deaths within 90 days, there was evidence of increased severity. Of four CDI cases where strain type BI was recovered during this initial pandemic wave, two developed a subsequent CDI recurrence, and one died within three months. There was also a concomitant decline in prevalence in REA types Y (6.7% vs. 27.3%). The incidence of strain type BI subsequently declined (26.7% vs 11.0%) after the initial COVID-19 wave (July 1, 2020 – March 31, 2022;

P=0.09). After adjusting for risk factors for CDI, the odds of developing an REA group BI CDI was higher during the first wave the COVID-19 pandemic when compared to the pre-pandemic time period (aOR: 6.41, 95% CI: 1.03 – 39.91;

Table 3). There was a subsequent decrease in odds of developing an REA group BI infection after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (aOR: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.04 – 0.99).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Key REA Groups Between Time Periods.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Key REA Groups Between Time Periods.

| First Pandemic Wave Compared to Pre-Pandemic Period* |

| |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI1) |

| REA2 Group BI (RT 027) |

6.41 (1.03 – 39.91) |

| REA Group DH (RT 106) |

2.87 (0.35 – 23.27) |

| REA Group Y (RT 014/020) |

0.13 (0.01 – 1.26) |

| Post First Pandemic Wave Compared to First Pandemic Wave† |

| REA Group BI (RT 027) |

0.20 (0.04 – 0.99) |

| REA Group DH (RT 106) |

0.35 (0.04 – 2.82) |

| REA Group Y (RT 014/020) |

3.56 (0.41 – 31.43) |

*Pre-Pandemic Period: October 1, 2019 – March 7, 2020; First Pandemic Wave: March 8, 2020 – June 30, 2020; †Post First Pandemic Wave: July 1, 2020 – March 31, 2022.

1CI: Confidence Interval; 2REA: Restriction Endonuclease Analysis. |

3. Discussion

There was a sudden, dramatic decline in CDI and rCDI diagnosis at HVAH beginning in April 2020. Others have similarly reported declines in CDI diagnosis during the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic [

6,

7], including within the VA Healthcare system [

8]. In contrast, some reports have found lower levels of CO-CDI but not HO-CDI [

9], while others have reported no significant change [

10], or modestly increased CDI rates in 2020 and 2021 [

11]. Some have suggested that rates of CD testing, rather than actual infections declined [

12], or that patients were more likely to delay getting care early in the pandemic [

13]. While our study was limited to a single large VA hospital, our analysis captured both CDI testing and treatment, and found no increase in empiric treatment of CDI. Reduced CDI levels at HVAH are therefore unlikely to be related solely to lower testing volume or delays in seeking treatment. The relevance of the decline in CDI should be considered in light of hospitalizations for COVID-19 and the high rate of antibiotic use in these patients. A review of 1007 abstracts found the majority (58-95%) of COVID-19 inpatients received empiric antimicrobial treatment to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia and other secondary infections despite low rates (8%) of bacterial or fungal coinfections [

14].

Co-infection with CDI and SARS-CoV-2 has occurred in a minority of patients with significant co-morbidities despite high rates of antibiotic use in COVID-19 patients [

14,

15]. We found this to be the case at HVAH with only 6 co-infected patients in 2020 and 2021, all of whom had histories of significant co-morbidities including cancer, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive lung disease, or hepatitis. Improved isolation measures in COVID-19 wards and antimicrobial stewardship programs potentially helped prevent outbreaks of CDI [

16]. Conversely, several other hospital acquired infections were significantly associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations [

7].

Infection control measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, including limiting visitors, increased hand-hygiene, use of personal protective equipment, application of universal precautions and isolation of COVID-19 patients on restricted wards may have helped to reduce the spread of CDI in healthcare settings [

17]. Likewise, community masking policies, business and school closures, prohibitions on indoor gatherings, and increased hand-hygiene and cleaning may have reduced spread of CDI and respiratory viral infections [

18,

19,

20].

Beginning on March 31, 2020, all non-essential healthcare visits at HVAH were cancelled or conducted by Telehealth. Nationwide there were striking declines in virtually all non-COVID-19 related healthcare encounters including visits to the emergency department [

21], outpatient hospital visits [

22], surgeries [

23], and even hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarctions [

24] that continued throughout 2020. HVAH hospital census data show a significant reduction in inpatient admissions that may have partially accounted for the drop in CDI among inpatients, though there was no such drop in outpatient volume to account for the decline in CDI among outpatients. Furthermore, we saw no indication of a shift toward CO-CDI with reduced healthcare usage and inpatient volume at HVAH.

There were nationwide increases in antibiotic prescriptions in hospitals with higher numbers of COVID-19 cases, but a sharp drop in nationwide outpatient antibiotic prescriptions coincident with the decrease in overall healthcare usage in 2020 [

25]. Since inpatient antibiotic use may have been primarily related to COVID-19 and was not associated with increased CDI, a decline in outpatient antibiotic use could have contributed to the decline in CO-CDI cases. Nationwide outpatient antibiotic prescriptions returned to near pre-pandemic levels by June 2021. However, outpatient antibiotic prescription numbers at HVAH were not lower in 2020, in contrast to the national trend. Other factors therefore likely contribute to the dramatic declines in NAAT+ stool tests, CDI cases, and CDI recurrence seen at HVAH in 2020 – 2021.

The addition of reflex to EIA toxin testing at HVAH in September 2019 resulted in significantly more patients being diagnosed with CD colonization and therefore not treated for CDI. Others have noted that inappropriate diagnosis of CDI has previously erroneously inflated CDI case numbers [

26] potentially resulting in over-treatment of patients without active infection. Our analysis includes a distinction between CDI and CD colonization and reveals a significant decline in all NAAT+ stool tests as well as CDI at HVAH in 2020 and 2021.

We found a significant spike in the prevalence of the hypervirulent CD strain BI (NAP1/RT 027) during the first four months of the pandemic at our hospital. This is in contrast to recent trends showing declining prevalence of this strain through June 2020 [

27]. While our data is from a limited sample set, we note that declining trends in BI shown by Gentry

et al were not apparent in 2020 in the West North Central region of the US, where our hospital is located.

BI is associated with more severe HO-CDI, and greater likelihood of CDI recurrence and death [

28,

29]. Despite the increased prevalence of this strain, we found no change in the likelihood of CDI recurrence from cases that occurred during this time, likely due to the small number of total cases. The increase in BI during the initial pandemic wave was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in REA group Y. Vendrik,

et al conducted surveillance of CDI in nine sentinel Dutch hospitals and performed PCR ribotyping on recovered CD isolates. They found an increase of RT 020 and decrease of RT 014 infections during the first year of the pandemic in the Netherlands that could not be explained by the spread of specific RT 020 clones [

13]. Both RT 020 and RT 014 correlate with REA Group Y strains [

30].

Beyond a modest increase in mean body temperature, we found no evidence that CDI patients at HVAH were sicker during the pandemic. This finding is unsurprising since HVAH CDI patients were almost exclusively a separate population from COVID-19 patients, and we found no evidence of greater CDI disease severity, more frequent recurrence, or that patients were delaying receiving care for CDI.

Here, we have shown that the lockdowns resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with a dramatic and ongoing decline in CD stool testing, CDI and CDI recurrence at one VA hospital. During the first wave of the pandemic, there was an increase in the prevalence of hypervirulent hospital-associated CD strain type BI/RT 027.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

We performed a retrospective review of all laboratory stool testing for CD and a review of the electronic medical record for CDI treatment at HVAH from January 1, 2015 – December 31, 2021. Most CDI cases (1105 of 1162; 95.1%) were confirmed with NAAT stool testing at HVAH (Xpert CD, Cepheid) or an outside hospital with documentation in the medical record. The remainder were treated empirically as CDI; no stool testing was performed, but on chart review, these patients had consistent symptoms and responded to specific antibiotic treatment for CDI. Prior to September 1, 2019, laboratory diagnosis of CDI utilized NAAT testing only. Beginning September 1, 2019 a NAAT+ test was reflexed to EIA toxin test for CD (Cdiff quick check complete, Alere/TechLab). In cases where stool testing was positive by NAAT (with or without a positive toxin test) and the medical record documented that treatment for CDI was unnecessary the case was considered CD colonization. HO-CDI, CO-CDI, and CO-HCFA-CDI were defined according to standard definitions [

31]. We defined rCDI as a second CDI diagnosis ≤90 days after successful initial treatment. Census of unique HVAH inpatients/outpatients was obtained from a search of Ambulatory Care Reporting Project records by Patient Administrative Services. Outpatient antibiotic use at HVAH was obtained from the PBM Power BI Outpatient Antibiotic Use Dashboard on the VHA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force SharePoint site.

4.2. REA Typing

NAAT+ stool samples collected during routine testing for CD at HVAH were frozen for subsequent testing, then thawed and inoculated on taurocholate-cefoxitin-cycloserine-fructose agar plates (TCCFA) and incubated for 48 – 72 hours in an anaerobic chamber [

32]. Distinct colonies with a typical CD morphology were subcultured onto BBL anaerobic blood agar and incubated anaerobically for 48 – 72 hours. CD isolates were frozen at -80⁰C prior to subsequent analysis. REA typing was performed on CD isolates as previously described [

33]. Briefly, total cellular DNA was subjected to

HindIII digestion, and DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel. The resulting restriction patterns were compared with patterns from previously characterized strains. Patterns showing a 90% similarity index were placed in the same REA group. Correlation of REA strain types with PCR Ribotype (RT) designations were shown in parentheses. [

30,

34].

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The χ2 and Fisher exact test were used to compare prevalence of CDI cases and REA types within groups between time periods. Student’s T-test was used to compare parametric variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare non-parametric variables across two dependent variables. If more than two dependent variables were compared, One-way ANOVA was utilized for parametric variables and Kruskal-Wallis for non-parametric variables. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

A series of multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the relationships between the time periods defined as 1) Pre-COVID (October 1, 2019 – March 7, 2020), 2) Initial COVID Wave (March 8, 2020 – June 30, 2020), and 3) Subsequent COVID Waves (July 1, 2020 – March 31, 2022) and CDI attributed to REA group BI, Y, and DH strains individually. The dates defining the initial COVID wave were chosen to capture all CDI cases that occurred during the week of the declaration of national emergency on March 13, 2020 to the end of the first spike in daily COVID-19 cases at our hospital. Variables included in the model included antimicrobial exposures within 6 months prior to CDI diagnosis that have previously demonstrated a high risk for CDI: 1) β-lactam antibiotics (cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminopenicillins, β-lactamase antibiotics), 2) macrolides, and 3) fluroquinolones. All other antibiotic exposures were grouped together as ‘other antibiotics’ excluding metronidazole and IV vancomycin. Metronidazole exposure was included as a separate covariate. Additionally, the model included age, immunocompromised status, and proton pump exposure. Immunocompromised status was defined as a history of hematologic malignancy, active chemotherapy, or immunomodulating medications. Patients with two or more separate clinical episodes of NAAT+ testing were considered separate ‘encounters.’ Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Results were reported adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

5. Conclusions

Here, we have shown that the pandemic lockdowns were associated with a dramatic and ongoing decline in Clostridioides difficile positive stool testing and CD infection rates at one VA hospital. We also found a temporary increase in the prevalence of the hypervirulent CD strain type BI (NAP1/RT 027).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.W., A.M.S., .SJ. and D.N.G.; Methodology, L.M.W., A.M.S., S.J., D.N.G. and L.G.; Validation, A.M.S. and L.G.; Formal Analysis, A.M.S. and L.G.; Investigation, L.M.W., A.C. and A.M.S.; Data Curation, L.M.W. and A.M.S.; Resources, S.P., C.M. and D.L.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, L.M.W. and A.M.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, L.M.W., A.M.S., A.C., C.M., S.P., D.L., D.N.G. and S.J.; Visualization, L.M.W., A.M.S., D.N.G. and S.J.; Supervision, C.M., D.L., D.N.G. and S.J.; Project Administration, D.N.G. and S.J.; Funding Acquisition, D.N.G. and S.J.

Funding

Salary support for LMW came from the VA CSP for “Optimal Treatment for Recurrent C. difficile Infection (OpTION).” A.M.S., A.C., C.M., L.G., S.P., D.L., D.N.G., and S.J. receive funding through the United States Veteran Affairs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Veterans Administration Central Institutional Review Board (Protocol CIRB 15-03; IRBNet #1613104 approved 11/10/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the VA CIRB because data was used for screening purposes to identify patients for potential enrollment in VA CSP#596. No identifiable data was used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), Marcus Johnson, MPH, MBA, MHA, the Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES), and the Hines Microbiology Lab for assistance. We thank Xue Li, PhD for help with statistics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Magill SSOL, E.; Janelle, S.J.; Thompson, D.L.; Dumyati, G.; Nadle, J.; Wilson, L.E.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Greissman, S.; Ray, S.M.; Beldavs, Z.; Gross, C., et al. Changes in Prevalence of Health Care–Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine 2018; 379: 1732-1744.

- Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG, Johnston H, Olson D, Farley MM et al. Trends in U.S. Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection and Outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1320-1330.

- Antibiotic / Antimicrobial Resistance (AR / AMR); Biggest Threats & Data; Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile). Centers for Disesase Control and Prevention 2021.

- Kelly CP. Can we identify patients at high risk of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection? Clinical Microbiology & Infection 2012; 18: 21-27.

- Shields K A-CR, Theethira TG, Alonso CD, Kelly C. Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection: From Colonization to Cure. Anaerobe 2015; 34: 59-73. [CrossRef]

- Sipos S, Vlad C, Prejbeanu R, Haragus H, Vlad D, Cristian H et al. Impact of COVID-19 prevention measures on Clostridioides difficile infections in a regional acute care hospital. Exp Ther Med 2021; 22: 1215. [CrossRef]

- Weiner-Lastinger LM, Pattabiraman V, Konnor RY, Patel PR, Wong E, Xu SY et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: A summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 12-25. [CrossRef]

- Evans ME, Simbartl LA, Kralovic SM, Clifton M, DeRoos K, McCauley BP et al. Healthcare-associated infections in Veterans Affairs acute-care and long-term healthcare facilities during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023; 44: 420-426. [CrossRef]

- Rose AN, Baggs J, Kazakova SV, Guh AY, Yi SH, McCarthy NL et al. Trends in facility-level rates of Clostridioides difficile infections in US hospitals, 2019-2020. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023; 44: 238-245.

- Nielsen RT, Dalby T, Emborg HD, Larsen AR, Petersen A, Torpdahl M et al. COVID-19 preventive measures coincided with a marked decline in other infectious diseases in Denmark, spring 2020. Epidemiol Infect 2022; 150: e138. [CrossRef]

- Advani SD, Sickbert-Bennett E, Moehring R, Cromer A, Lokhnygina Y, Dodds-Ashley E et al. The Disproportionate Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Healthcare-Associated Infections in Community Hospitals: Need for Expanding the Infectious Disease Workforce. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: e34-e41. [CrossRef]

- Hawes AM, Desai A, Patel PK. Did Clostridioides difficile testing and infection rates change during the COVID-19 pandemic? Anaerobe 2021; 70: 102384.

- Vendrik KEW, Baktash A, Goeman JJ, Harmanus C, Notermans DW, de Greeff SC et al. Comparison of trends in Clostridioides difficile infections in hospitalised patients during the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective sentinel surveillance study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 19: 100424. [CrossRef]

- Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, Ranganathan N, Skolimowska K, Gilchrist M et al. Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals With Coronavirus: A Rapid Review To Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: 2459-2468. [CrossRef]

- Granata G, Petrosillo N, Al Moghazi S, Caraffa E, Puro V, Tillotson G et al. The burden of Clostridioides difficile infection in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaerobe 2022; 74: 102484. [CrossRef]

- Kullar R JS, McFarland LV, Goldstein EJC. Potential Roles for Probiotics in the Treatment of COVID-19 Patients wnad Prevention of Complications Associated with Increawed Antibiotic Use. Antibiotics 2021; 10: 408.

- Ochoa-Hein E, Rajme-López S, Rodríguez-Aldama JC, Huertas-Jiménez MA, Chávez-Ríos AR, de Paz-García R et al. Substantial reduction of healthcare facility-onset Clostridioides difficile infection (HO-CDI) rates after conversion of a hospital for exclusive treatment of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49: 966-968.

- Prevention CfDCa. FluView Interactive: ILI and Viral Surveillance.

- Wiese AD, Everson J, Grijalva CG. Social Distancing Measures: Evidence of Interruption of Seasonal Influenza Activity and Early Lessons of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e141-e143.

- Wee LEI, Conceicao EP, Tan JY, Magesparan KD, Amin IBM, Ismail BBS et al. Unintended consequences of infection prevention and control measures during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49: 469-477. [CrossRef]

- Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits - United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69: 699-704.

- McCracken CE, Gander JC, McDonald B, Goodrich GK, Tavel HM, Basra S et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Trends in Outpatient Clinic Utilization: A Tale of 2 Departments. Med Care 2023; 61: S4-s11.

- O’Reilly-Shah VN, Van Cleve W, Long DR, Moll V, Evans FM, Sunshine JE et al. Impact of COVID-19 response on global surgical volumes: an ongoing observational study. Bull World Health Organ 2020; 98: 671-682. [CrossRef]

- Gluckman TJ, Wilson MA, Chiu ST, Penny BW, Chepuri VB, Waggoner JW et al. Case Rates, Treatment Approaches, and Outcomes in Acute Myocardial Infarction During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5: 1419-1424. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan A. Antibiotic Resistance (AR), Antibiotic Use (AU), and COVID-19. In: Bacteria PACoCA-R (ed), 2021.

- Lee HS, Plechot K, Gohil S, Le J. Clostridium difficile: Diagnosis and the Consequence of Over Diagnosis. Infect Dis Ther 2021; 10: 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Gentry CA, Williams RJ, 2nd, Campbell D. Continued decline in the prevalence of the Clostridioides difficile BI/NAP1/027 strain across the United States Veterans Health Administration. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021; 100: 115308.

- Figueroa I, Johnson S, Sambol SP, Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Gerding DN. Relapse versus reinfection: recurrent Clostridium difficile infection following treatment with fidaxomicin or vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55 Suppl 2: S104-109. [CrossRef]

- Petrella LA, Sambol SP, Cheknis A, Nagaro K, Kean Y, Sears PS et al. Decreased cure and increased recurrence rates for Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic C. difficile BI strain. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55: 351-357. [CrossRef]

- Kociolek LK, Perdue ER, Fawley WN, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Johnson S. Correlation between restriction endonuclease analysis and PCR ribotyping for the identification of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile clinical strains. Anaerobe 2018; 54: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Multidrug-resistant organisms and Clostridioides difficile infection (MDRO/ CDI) module. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

- Kociolek LK, Patel SJ, Shulman ST, Gerding DN. Molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections in children: a retrospective cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36: 445-451. [CrossRef]

- Clabots CR, Johnson S, Bettin KM, Mathie PA, Mulligan ME, Schaberg DR et al. Development of a rapid and efficient restriction endonuclease analysis typing system for Clostridium difficile and correlation with other typing systems. J Clin Microbiol 1993; 31: 1870-1875. [CrossRef]

- Manzo CE, Merrigan MM, Johnson S, Gerding DN, Riley TV, Silva J, Jr. et al. International typing study of Clostridium difficile. Anaerobe 2014; 28: 4-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).