Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

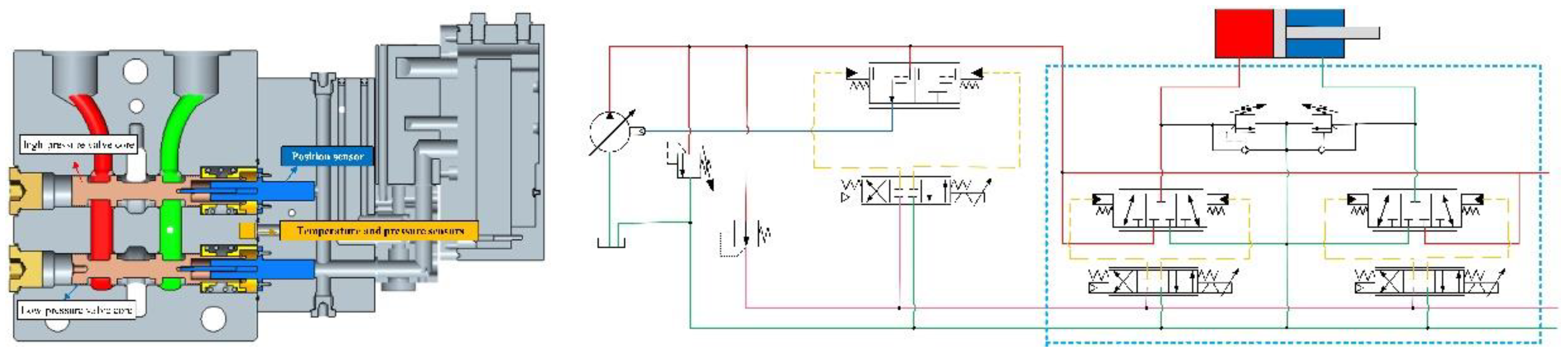

2. Problem Formulation

| supply pressure | Return pressure | ||

| Left chamber pressure of the main valve | Main valve right chamber pressure | ||

| Pressure bearing area of the left chamber of the main valve | Pressure bearing area of the right chamber of the main valve | ||

| Main valve core quality | viscous friction coefficient | ||

| Volume of the left chamber of the main valve | Volume of the right chamber of the main valve | ||

| Initial volume of the left chamber of the main valve | Initial volume of the right chamber of the main valve | ||

| Elastic bulk modulus | Main valve core driving force | ||

| Control input voltage | Main valve spring stiffness | ||

| Pilot valve flow coefficient | Hydraulic oil density | ||

| Load flow rate input to the main valve | Pilot valve electrical gain coefficient |

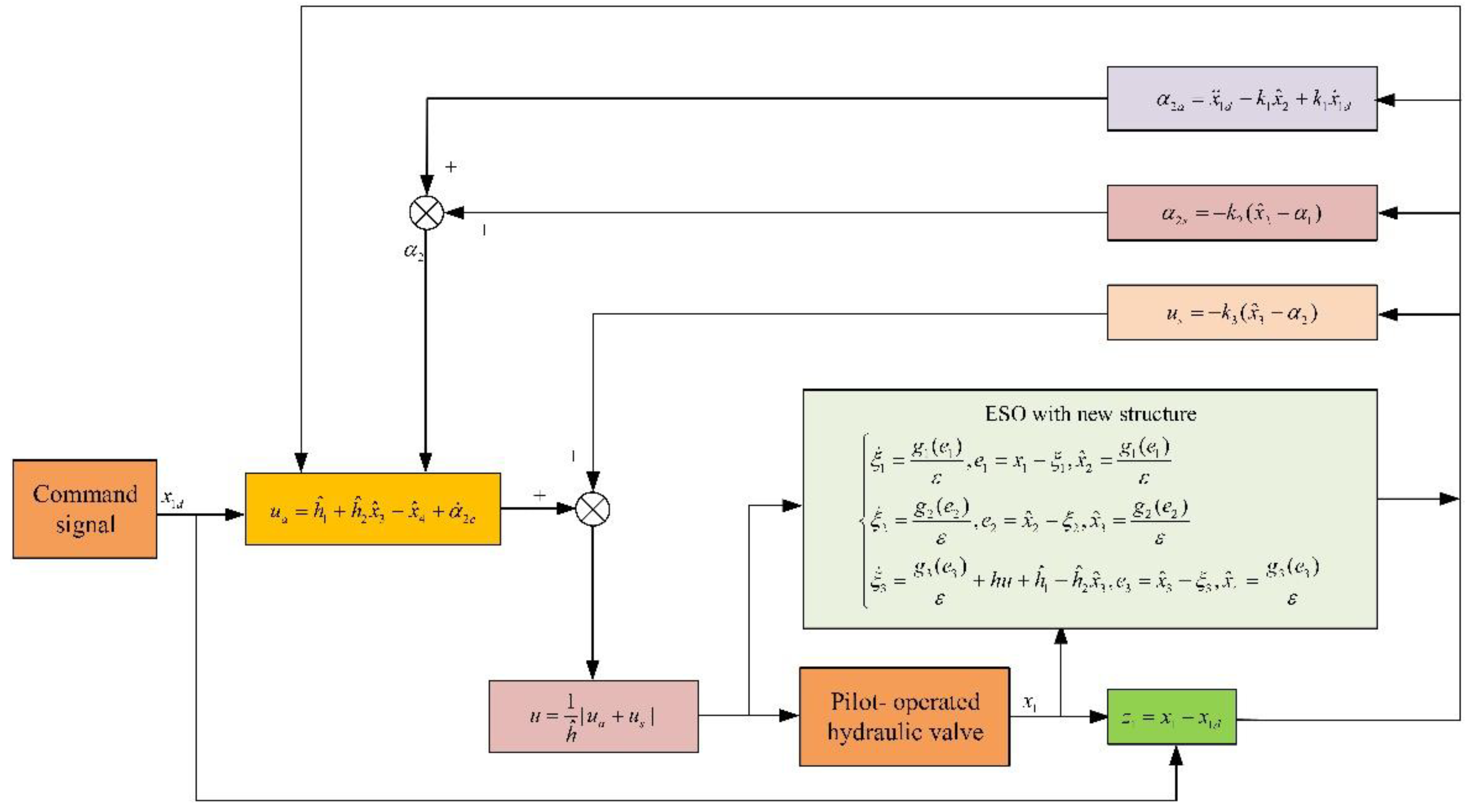

3. Cascade Observer and Output Feedback Controller Design

3.1. Model Design and Issues to Be Addressed

3.2. Design of Extended State Observer with Cascade Structure

3.3. Formatting of Mathematical Components

3.4. Design of Output Feedback Controller

3.5. Proof of Convergence of Backstepping Controller

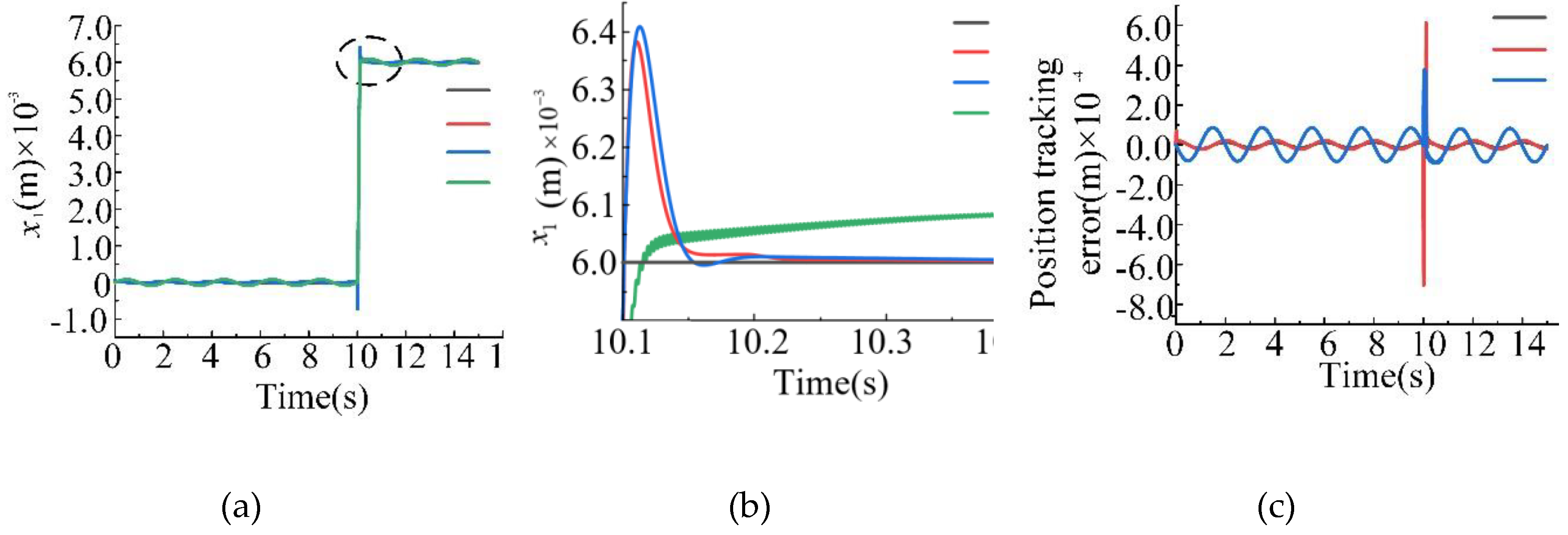

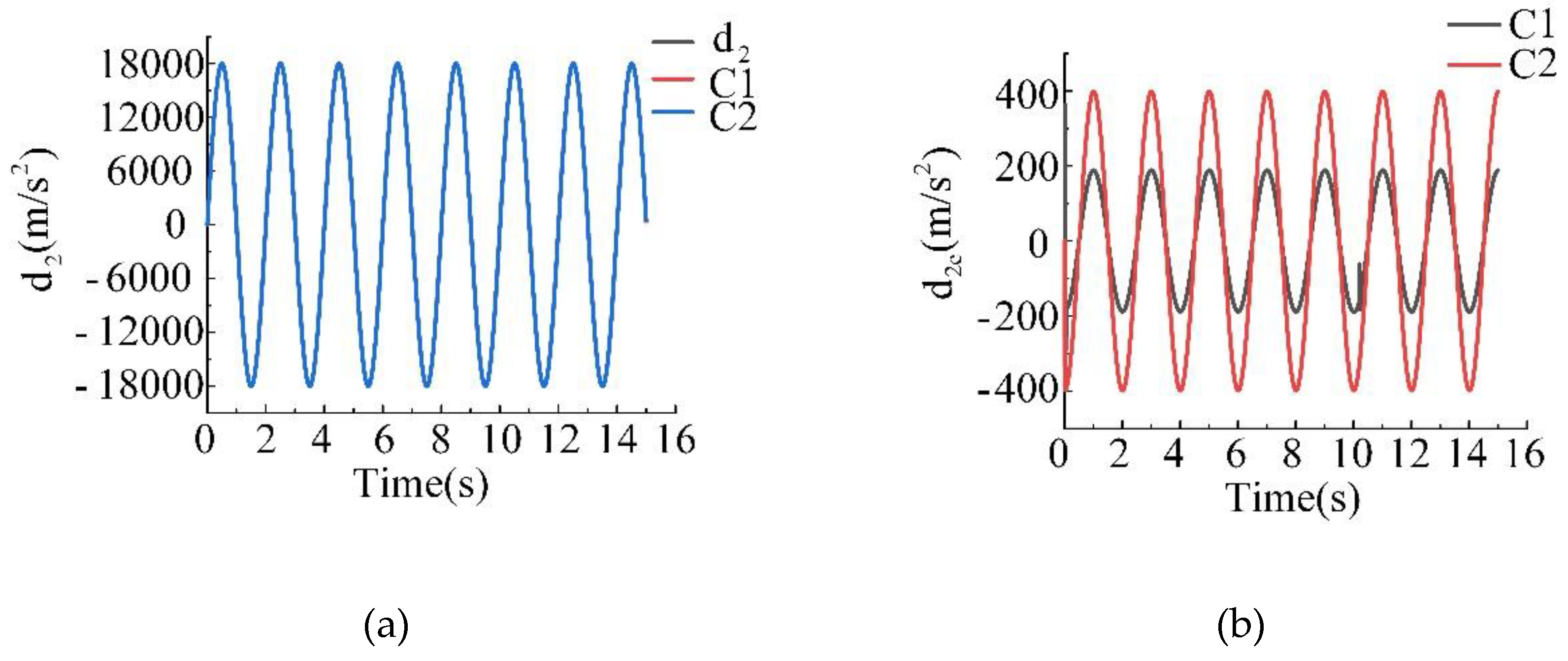

4. Application Verification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LESO | Linear extended state observer |

| USE | Uniform exponential stability |

| IARC | Indirect adaptive robust control |

| DT-SMC | Discrete-time sliding mode controller |

| ADRC | Active Disturbance Rejection Control |

| GESO | Generalized extended state observer |

| DCMSS | Disturbance Compensation Motion Control System for Servo Motors |

| LVDT | Linear variable differential transformer |

| ESO | Extended state observer |

| supply pressure | |

| Left chamber pressure of the main valve | |

| Pressure bearing area of the left chamber of the main valve | |

| Main valve core quality | |

| Volume of the left chamber of the main valve | |

| Initial volume of the left chamber of the main valve | |

| Elastic bulk modulus | |

| Control input voltage | |

| Pilot valve flow coefficient | |

| Load flow rate input to the main valve | |

| Return pressure | |

| Main valve right chamber pressure | |

| Pressure bearing area of the right chamber of the main valve | |

| viscous friction coefficient | |

| Volume of the right chamber of the main valve | |

| Initial volume of the right chamber of the main valve | |

| Main valve core driving force | |

| Main valve spring stiffness | |

| Hydraulic oil density | |

| Pilot valve electrical gain coefficient | |

| Represents the modeling error including nonlinear friction and the concentrated disturbance caused by external disturbances | |

| System load force modeling error | |

| State variable | |

| Flow gain corresponding to the displacement of the pilot valve core, | |

| Expected load pressure signal | |

| Define error vector | |

| System modeling error | |

| State-transition matrix of the system | |

| Disturbance in the system | |

| Hurwitz matrix | |

| Positive-definite matrix |

References

- B. Yao, F. Bu, J. Reedy and G. T. C. Chiu, „Adaptive robust motion control of single-rod hydraulic actuators: Theory and experiments,” Proceedings of the 1999 American Control Conference (Cat. No. 99CH36251), San Diego, CA, USA, 1999, pp. 759-763 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- C. Guan and S. Pan, „Nonlinear Adaptive Robust Control of Single-Rod Electro-Hydraulic Actuator With Unknown Nonlinear Parameters,” in IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 434-445, May 2008. [CrossRef]

- W. Sun, H. Gao and B. Yao, „Adaptive Robust Vibration Control of Full-Car Active Suspensions With Electrohydraulic Actuators,” in IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 2417-2422, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohanty and B. Yao, „Indirect Adaptive Robust Control of Hydraulic Manipulators With Accurate Parameter Estimates,” in IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 567-575, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wei, L. Qian, S. Nie and Q. Yin, „Adaptive Backstepping Sliding Mode Control for Electro-hydraulic Position Servo System of The Artillery Projectile Transfer Arm,” 2019 IEEE 4th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chengdu, China, 2019, pp. 893-898. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin, Y. Shi and R. Burton, „Modeling and Robust Discrete-Time Sliding-Mode Control Design for a Fluid Power Electrohydraulic Actuator (EHA) System,” in IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1-10, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Fang Yiming, Jiao Zongxia, Wang Wenbin, et al. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode control for hydraulic servo position systems of rolling mills [J]. Journal of Electrical Machinery and Control,2011,15(10):95-10. [CrossRef]

- Q. Guo, J. Yin, T. Yu and D. Jiang, „Saturated Adaptive Control of an Electrohydraulic Actuator with Parametric Uncertainty and Load Disturbance,” in IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 7930-7941, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Guichao Yang, Jianyong Yao, „Output feedback control of electro-hydraulic servo actuators with matched and mismatched disturbances rejection, „Journal of the Franklin Institute, vol 356, Issue 16,2019. [CrossRef]

- Han J. From PID to Active Disturbance Rejection Control[J]. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics,2009,56(3).

- J. Yao, Z. Jiao, D. Ma, Extended-state-observer-based output feedback nonlinear robust control of hydraulic systems with backstepping, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 61 (11) (2014) 6285–6293.

- L. Zhou, L. Cheng, C. Pan and Z. Jiang, „Generalized Extended State Observer Based Speed Control for DC Motor Servo System,” 2018 37th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Wuhan, China, 2018, pp. 221-226. [CrossRef]

- Kim W,Won D,Shin D, et al. Output feedback nonlinear control for electro-hydraulic systems[J]. Mechatronics,2012,22(6).

- E. H. El Yaagoubi, A. El Assoudi and H. Hammouri, „High gain observer: attenuation of the peak phenomena,” Proceedings of the 2004 American Control Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 2004, pp. 4393-4397 vol.5. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Khalil, „High-Gain Observers in Feedback Control: Application to Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors,” in IEEE Control Systems Magazine, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 25-41, June 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, J. Wang, D. Shi, J. Wu and L. Shi, „Event-Triggered Sampled-Data Control: An Active Disturbance Rejection Approach,” in IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 2052-2063, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Chong, D. Nešić, R. Postoyan and L. Kuhlmann, „Parameter and State Estimation of Nonlinear Systems Using a Multi-Observer Under the Supervisory Framework,” in IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 60, no. 9, pp. 2336-2349, Sept. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ricardo G. Sanfelice, Laurent Praly, „On the performance of high-gain observers with gain adaptation under measurement noise, „Automatica, vol 47, Issue 10,201. [CrossRef]

- D. Astolfi and L. Marconi, „A High-Gain Nonlinear Observer With Limited Gain Power,” in IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 60, no. 11, pp. 3059-3064, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Maopeng Ran, Juncheng Li, Lihua Xie, „A new extended state observer for uncertain nonlinear systems,” Automatica, vol 131, 2021,109772. [CrossRef]

- Ziying Lin, Jianyong Yao, Wenxiang Deng, „Input constraint control for hydraulic systems with asymptotic tracking, „ ISA Transactions, Volume 129, Part A,2022,Pages 616-627, ISSN 0019-0578. [CrossRef]

- Rugh, W. J. 1996. Linear System Theory (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

| (kg) | 1.05 | (Pa) | |

| (m²) | (N/m) | 15580 | |

| (m³) | (N/(m/s)) | 350 | |

| (Pa) | (Pa) | 0 | |

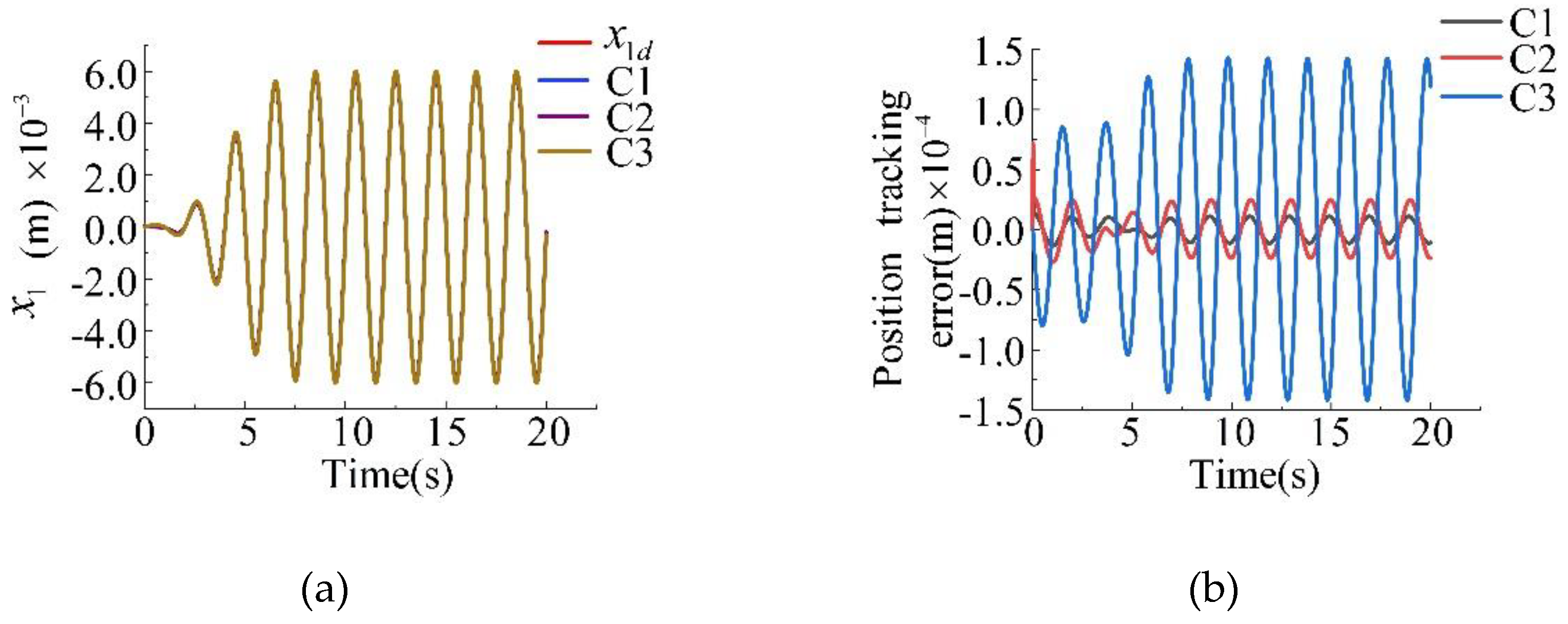

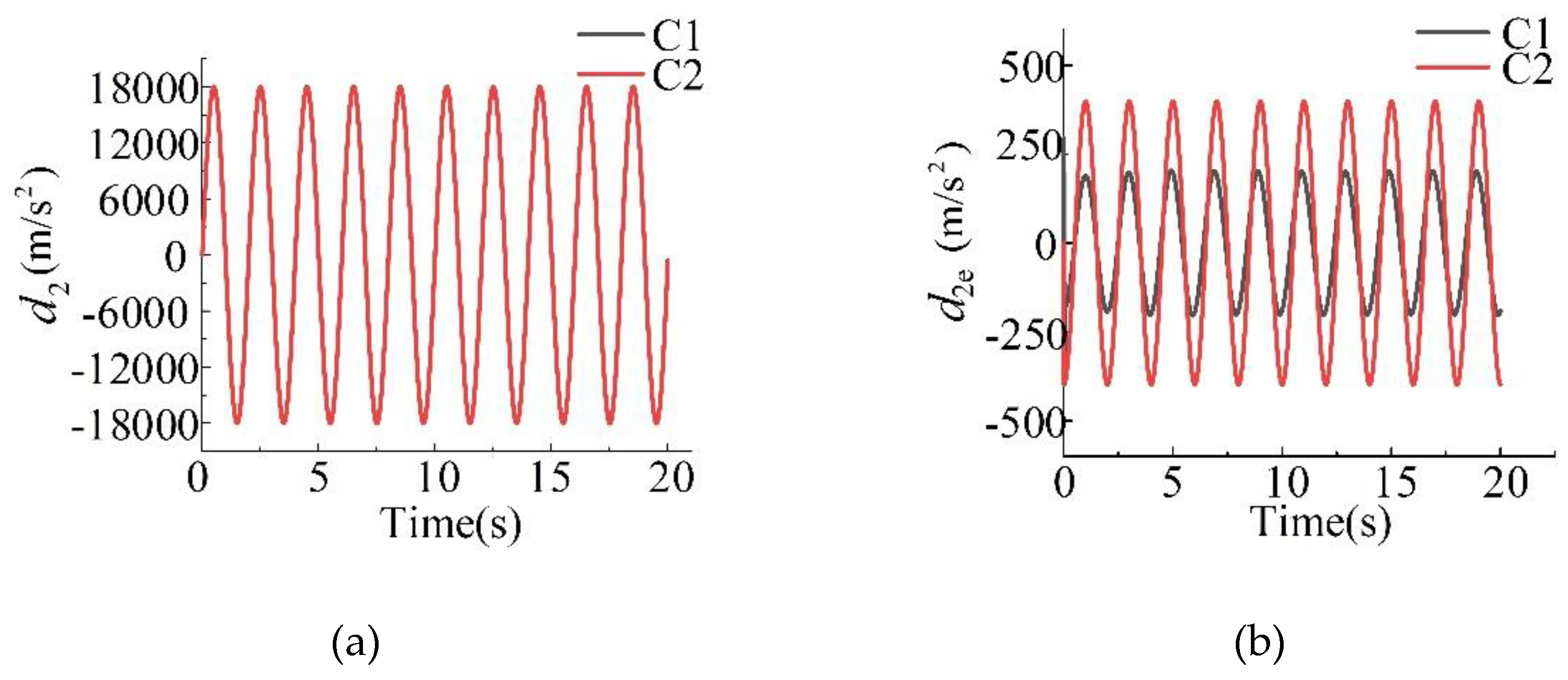

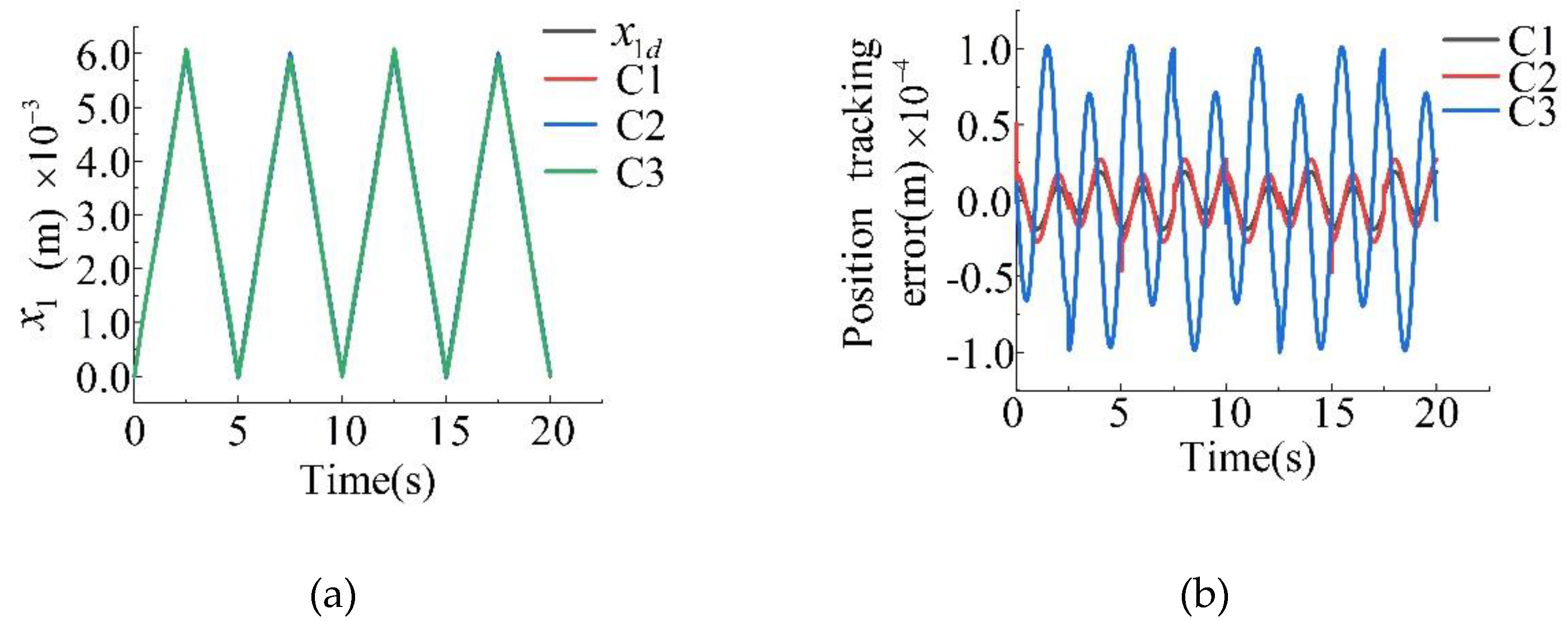

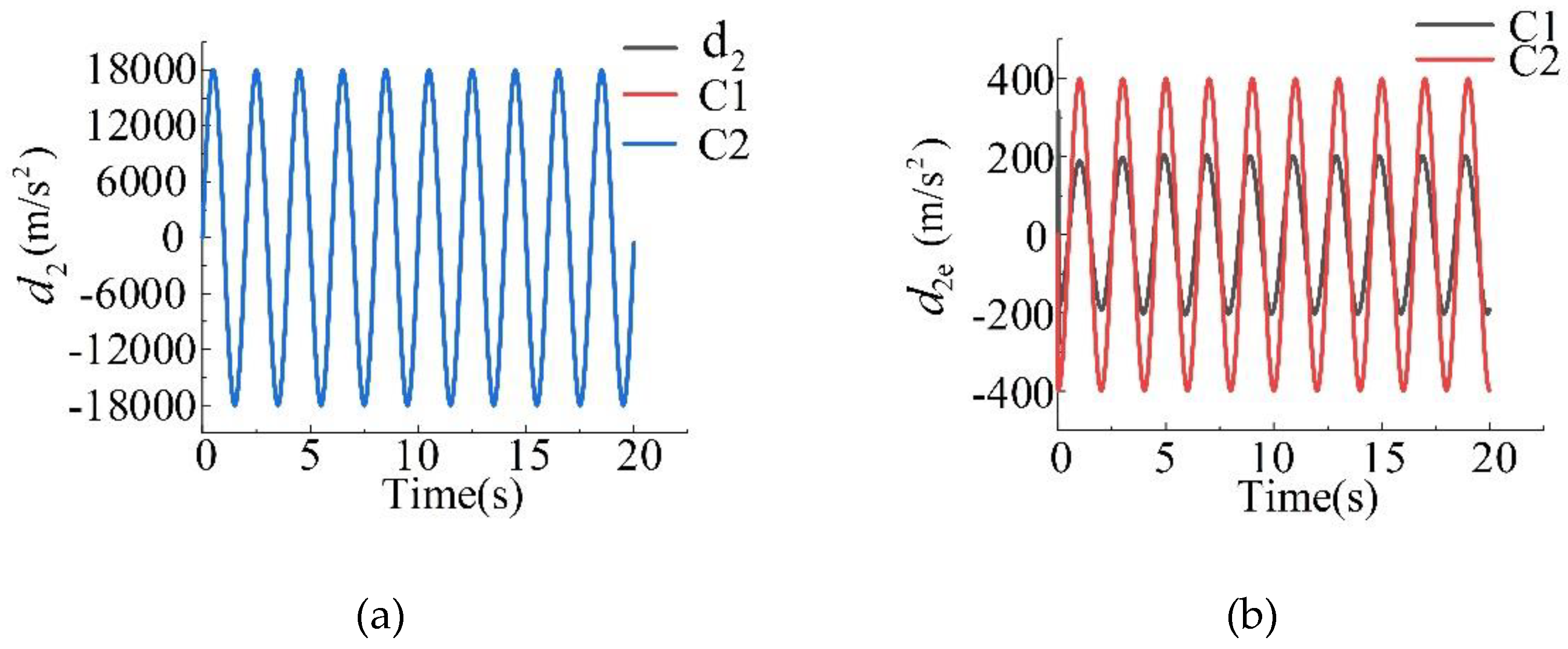

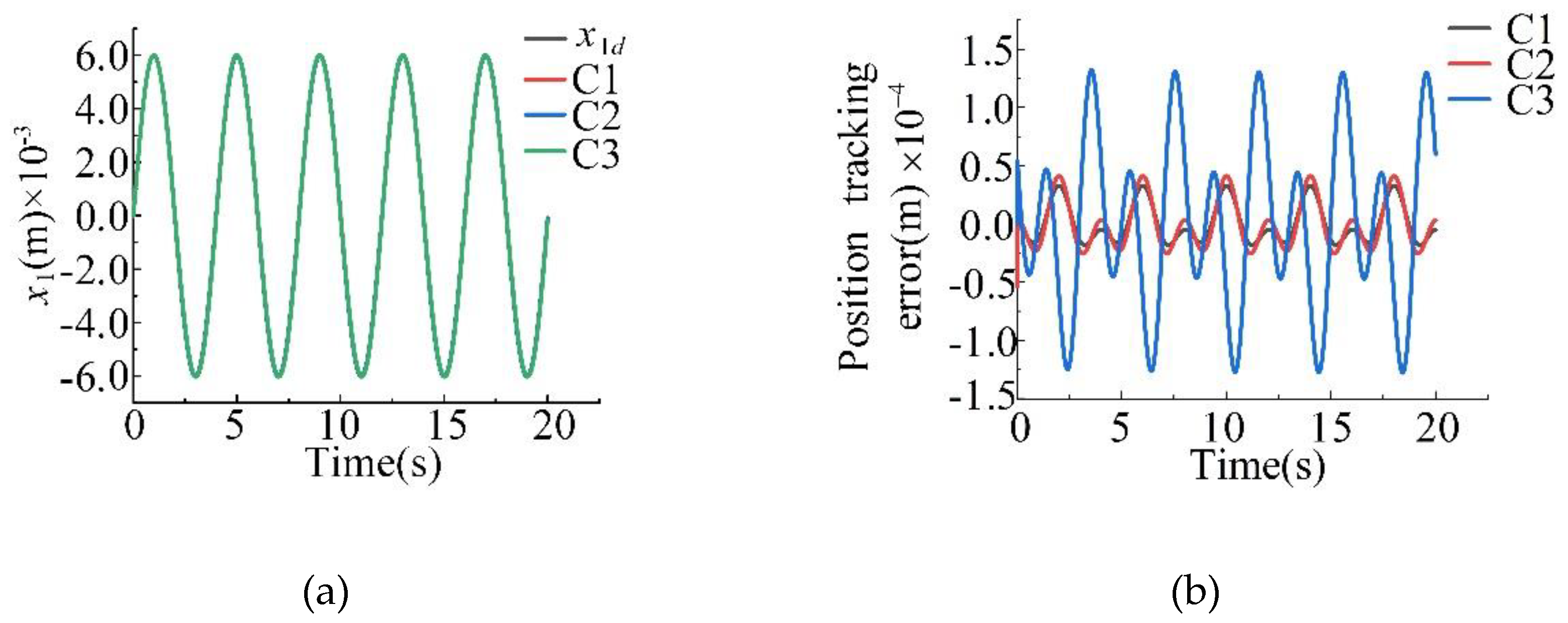

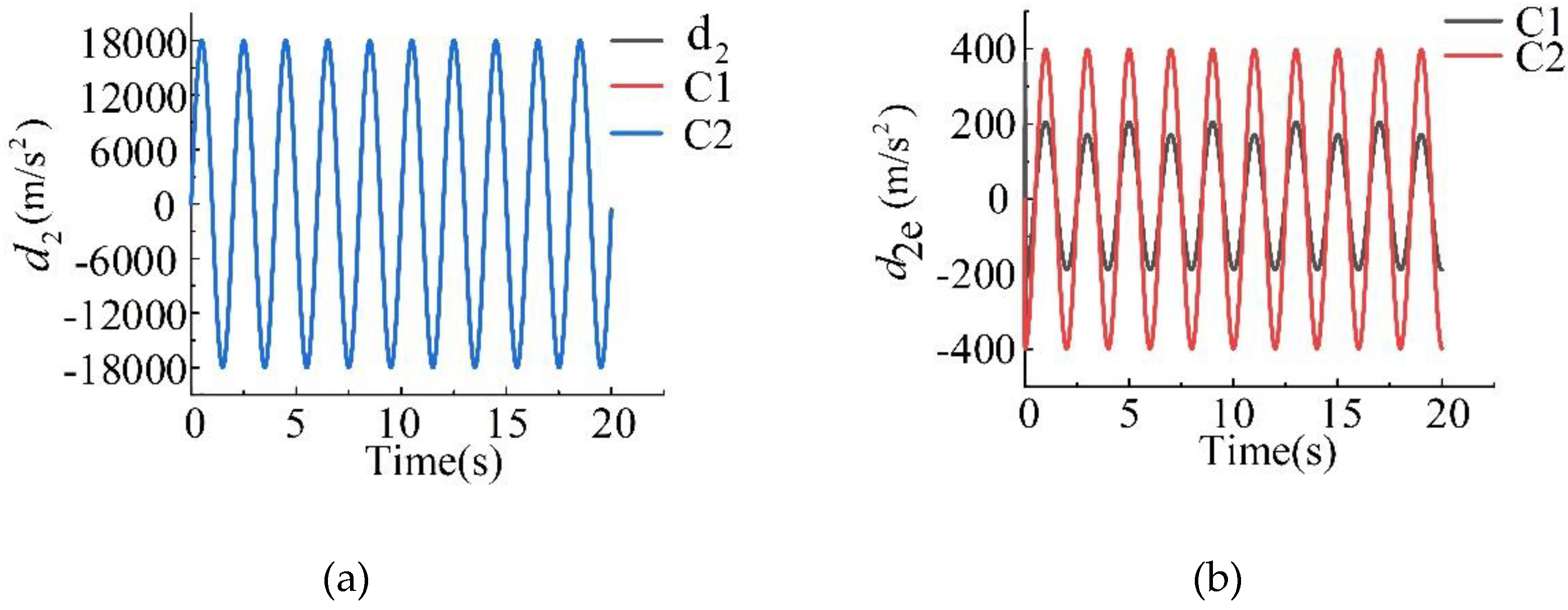

| C1 | |

| C2 | |

| C3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).