1. Introduction

Electrical stimulation (ES) has demonstrated a wide range of effects on various biological processes, including galvanotaxis and cell proliferation [

1]. Additionally, it exhibits anti-inflammatory properties through the actions of specialized cells in the autonomic nervous system, such as in bioelectronic medicine and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which depend on the inflammatory reflex [

2,

3]).

Based on this, it is clear that ES anti-inflammatory applications hold great translational potential, given the ubiquitous role of inflammation in the silent subclinical inflammatory phase that precedes non-communicable diseases (NCDs), whose impact can be recognized to be pandemic [

4] and mobilizes worldwide efforts (Sustainable Development Goal, SGD 3.4).

Two major challenges are to be faced to proceed to actual medical translation: the generation of a continuum between basic research findings and medical applications (mechanistic insights into the effectiveness of ES) and standardization of experimental settings enabling meta-analyses.

It is to contribute directly to both challenges that we recently proposed investigating the impact of electrical stimuli on inflammation and wound healing within a three-dimensional bioconstructed sample, highly reproducible, for the systematic observation of ES effects in different contexts [

5]. This recent work has shown how, at the transcriptional-metabolomic level, ES effects are dependent on the surrounding microenvironment, whether physiological or inflamed, on the nature of the stimulus, and, of course, on time. Notably, in our experimental setting, direct current (DC) stimuli tend to have a more pronounced effect compared to alternate current (AC) ones. In particular, DC at

shows moderate pro-inflammatory activity in a physiological context, while DC at

exhibits, in our setting, anti-inflammatory properties. Further, AC at

and

is observed to promote proliferation in inflamed states, with an inverse effect under physiological conditions. Finally, we observed senescence-like events: first as a natural process occurring over time (i.e., in the absence of stimuli), and faster so in inflamed samples; and second under DC at

and AC at

, in physiological samples.

Building upon these insights, the present study explores the epigenomic dimension, focusing on DNA methylation. Our objective is to examine whether different types of electrical stimuli can modulate DNA methylation patterns in such a short time frame (

). Further, given the long established ability of methylation signals to correlate with biological aging (

methylage) [

6,

7], we exploit the specific cellular epigenetic clock EpiTOC [

8] for this additional analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The experimental setup is described in detail in [

5]. Briefly, we constructed a 3D

in vitro model composed of a collagen matrix embedded with human fibroblasts overlaid with human keratinocytes, stimulated with four different types of ES (

in DC and

at

in AC) sampled at three time points (baseline, labeled 0, and then

post-stimulation). Inflammation (INFL) was mimicked by administration of TNF-

prior to electrostimulation, non-INFL samples are labeled physiologic (PHYS). The study design is reported in

Table 1. All samples are intuitively named after the labels described.

2.2. Methylomics

DNA was extracted using Quick-DNA/RNA™Microprep Plus Kit from Zymo Research (Irvine, CA, USA), stored at -80 ℃and further processed by bisulfite treatment with Zymo EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA methylation was assessed via Infinium MethylationEPIC v1.0 BeadChip Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) following the producer’s indications. The iScan System (Illumina, San Diego, USA) was used to read the BeadChips and methylation data was obtained in the form of Intensity Data (IDAT) files and processed using the

ChAMP package in R [

9]. Data are stored and available on GEO with ID GSE280243.

2.3. Differential Analysis

Following data import, quality control was performed using Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) and density plots to assess data distribution and identify outliers. Normalization with Beta Mixture Quantile dilation (BMIQ), and batch effect correction (

ComBat, accounting for ’Run’ and ’Array’), were checked through Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots. After

logit-transforming the batch-corrected counts, the interactions between State, Time, and Stimulus was linearly modeled and differential analysis was run using the

limma package [

10]. Differentially Methylated Probes (DMPs) were finally identified using the

topTable function.

2.4. Enrichment

To gain insights into the biological pathways and processes associated with the DMPs, enrichment was computed with function

gometh from the

missMethyl package [

11] for the GO

molecular functions categories. CpG sites are mapped to Entrez Gene IDs, and enrichment is computed taking into account both the number of CpG sites per gene on the EPIC array and the CpGs annotated for multiple genes. Results are presented as dotplots where the intensity of the color corresponds to the quantity of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the radius is inversely proportional to the corrected q-value (FDR-qvalue Bonferroni-corrected for the number of contrasts analyzed). Enrichment is run contrast-wise, however, for the sake of readability, discussion and comparison to previous work [

5], are run with constrasts grouped under six main questions, see

Table 1).

2.5. Methylage

To apply the EpiTOC model [

8] and calculate the corresponding

methylage, binary variables were constructed on the batch-corrected, normalized

stored in fifty-seven matrices (one per contrast). Statistical comparisons between the two sample groups in each contrast were then performed using t-test. For conditions with one sample (unbalanced number of biological replicae), the sample’s value was simply duplicated to allow for the test to proceed. Correction for multiple hypotheses was computed with a diversity of approaches using the

mt.rawp2adjp function from R package

multtest.Contrasts, t-statistics, p-values, and accelerations are reported in Table S1.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, to guide our exploration across the numerous samples available, we explore six questions, listed in the first column of

Table 2 via the enrichment results of the corresponding fifty-seven contrasts shown in the second column. To ease the discussion, the third column recalls the joint effects on transcriptomics and metabolomics extracted from [

5], and finally the fourth column summarizes the discussion on methylomics that is presented below. In particular, enrichment is presented question-wise with a dot plot, indicating enrichment of the contrasts (on the x-axis) for the gene sets on the y-axis. The challenge we face lies in the large number of contrasts, given the complex experimental design.

Finally, to ease the reading,

methylage results are briefly discussed here, due to their limited significance, with the complete results of the analysis being made available in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. Results that show a statistically significant difference in methylage (t-test) include the conditions for which transcriptomics suggested an activity possibly related to senescence [

5], i.e. ageing of the sample due to inflammation (no stimuli) and ageing associated to the DC5 stimulus in PHYS conditions. The latter is associated on the transcriptomics side to

transitional activities (i.e. referred to the process associated with a transition from a state to another) due to the deactivation of EMT and upregulation of MYC, which echoes the increased methylage observed in several cancer types [

12]. A mild

decrease in ageing when inflamed samples undergo DC1 stimulation can also be observed. None of those, however, survives statistical correction for multiple hypotheses (Table S1, PHYS.48.DC5vsNO, PHYS.1.DC5vsDC1, PHYS.1.DC5vsAC100, highlighted in yellow).

Nevertheless, we deem remarkable to report one exception (Table S1 highlighted in green): the difference between INFL and PHYS samples presents at 48h a positive (

) significant (

) difference that (almost) survives multiple hypothesis correction (

). The interesting observation lies in the vanishing, and partial reversing, of this difference when

and

s are applied: at

, comparisons between PHYS and INFL samples, following these stimuli (Table S1, highlighted in pink), report a one order of magnitude smaller, mildly negative, non-significant difference, suggesting that these stimuli have the potential to control the senescence process associated to INFL. This is not the case for

(in blue), which, as shown earlier [

5] and here reported in

Table 2 Question 2 increases inflammation in PHYS samples, reducing their difference with INFL samples. Certainly, more investigation is warranted in this direction to elucidate the potential relevance of these observations.

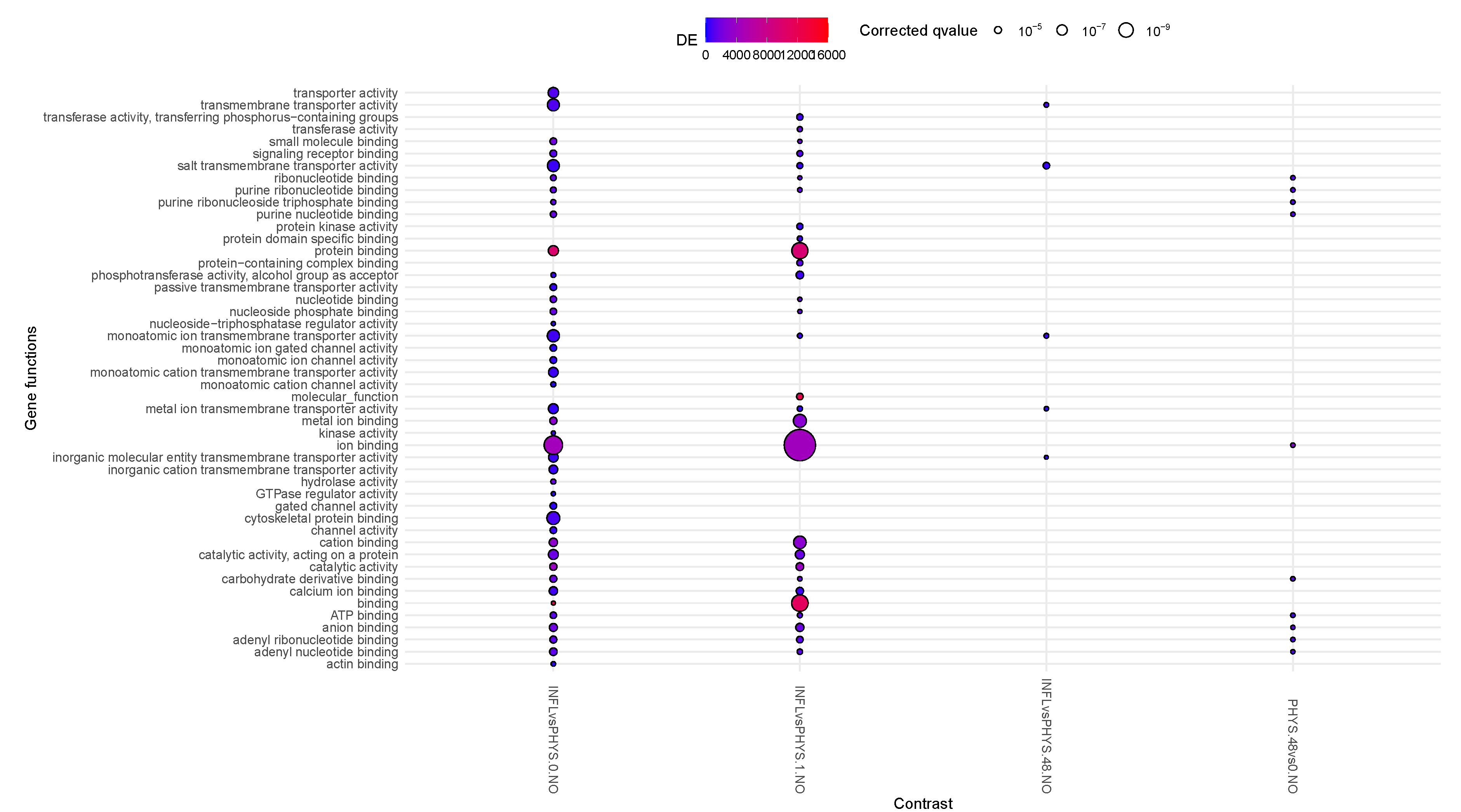

3.1. Question 1: Impact of Time

Inflamed samples do not show statistically relevant changes, while PHYS samples present over time a decrease in binding (ion, cation) (

Figure 1). The difference between PHYS and INFL at the methylomic level is represented by a reduced transmembrane transporter activity, stable over time and supported at earlier times by transient enhanced

ion binding and

catalitic activity which is coherent with a more pronounced cell stress response in INFL versus PHYS, also supported by an increase in methylage over time, whose acceleration is more relevant in INFL.

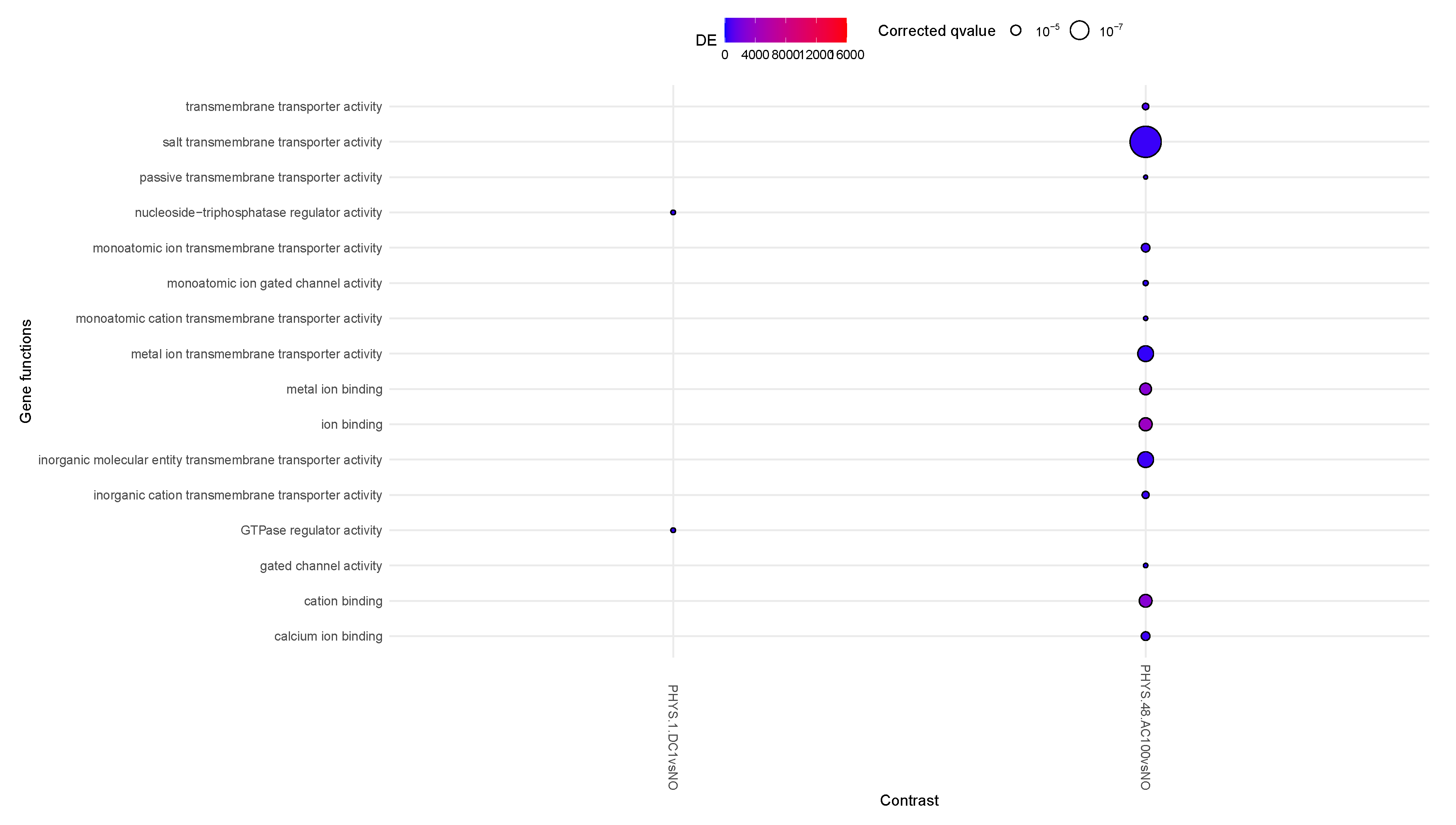

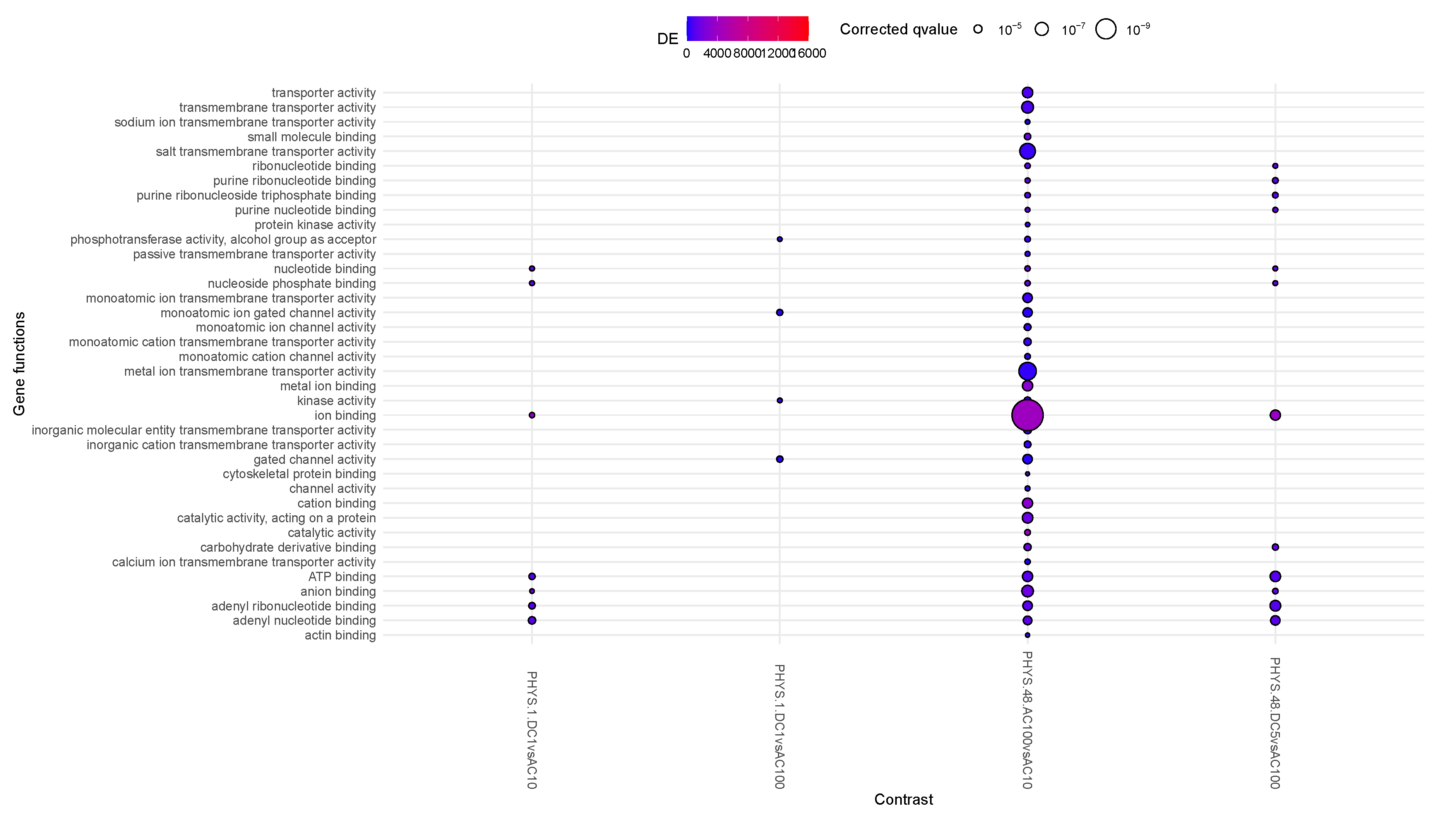

3.2. Question 2: Impact of Stimuli on Physiological Samples

In

Figure 2, very little activity appears to involve differential methylation. At steady state, only AC100 appears to strongly decrease transmembrane transportation and mildly increase ion binding. Transiently for DC1, we observe a decrease in GTPase regulator activity. DC5 appears to mildly increase methylage, supporting the idea that such stimuli on non-inflamed samples should be administered with caution.

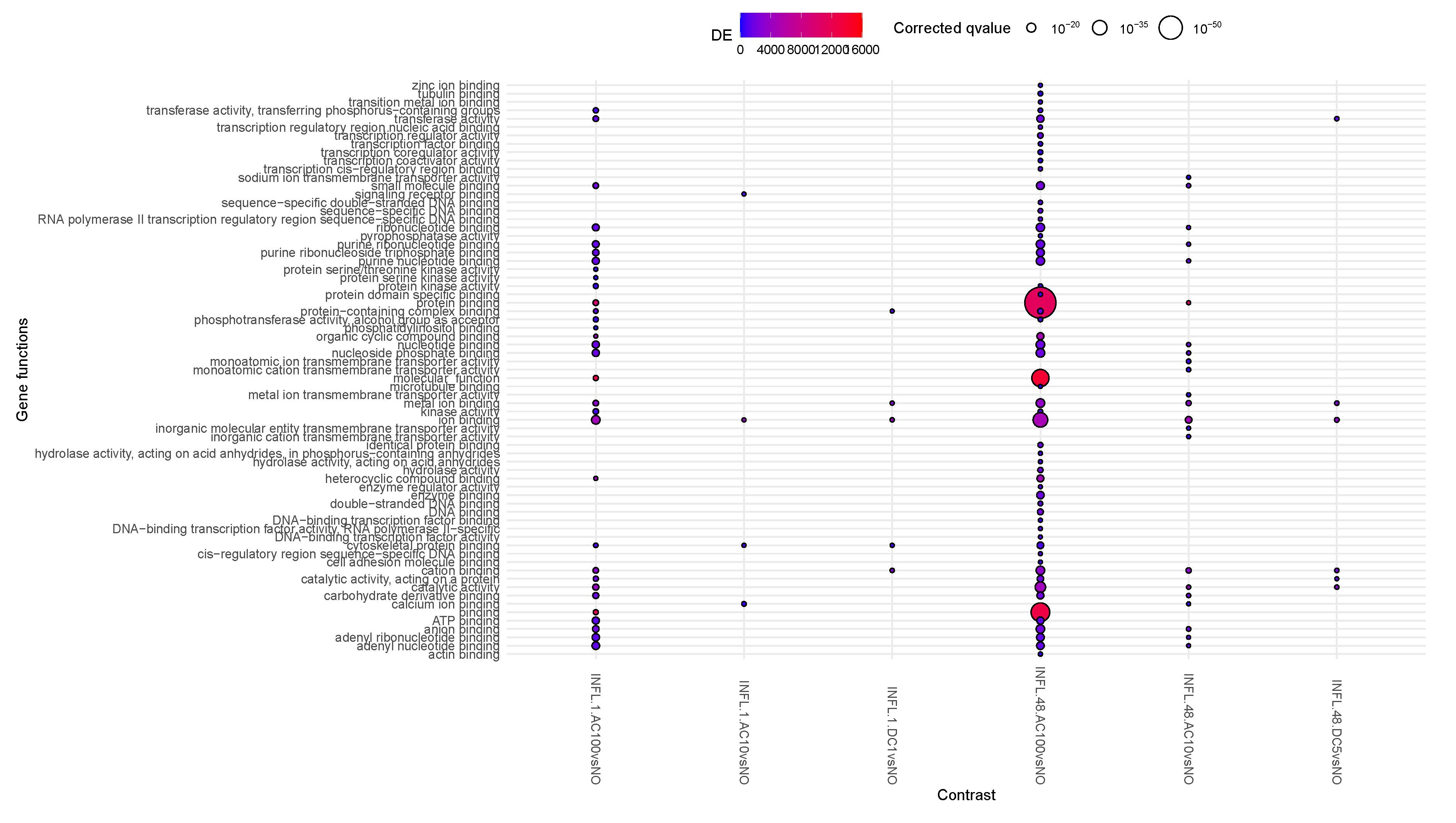

3.3. Question 3: Effects of Stimuli on Inflamed Samples

Moving down along the enriched functions (

Figure 3), the major number of relevant contrasts refer to AC100, at all time points, with large enhancement of protein binding activity, and a reduction of the translational activity at time 48h. Overall, the reduction in translational activity and proliferation supported at the transcriptional and epigenomic level possibly indicates a complex interaction of cellular stress responses, epigenetic modifications, shifts in gene expression patterns, potential differentiation cues, and changes in cellular communication. Together, these factors drive a transition from proliferation to maintenance and adaptation mechanisms under stress conditions. Methylation is a robust and long-lasting epigenetic modification, retaining a degree of plasticity, allowing to respond to developmental and environmental factors over time. This could therefore imply a stable and therefore durable effect of the observed phenomena triggered by AC100. In AC10, some of the same protein binding activity is visible, although milder, suggesting a frequency-dependent intensity of this activity, and transcription is replaced by transmembrane transporter activity.

presents in transcriptomics an early inflammatory activity followed by proliferation, echoing the phase of wound healing (epithelial mesenchymal transition type 2) [

13], accompanied by a mild reduction in methylage.

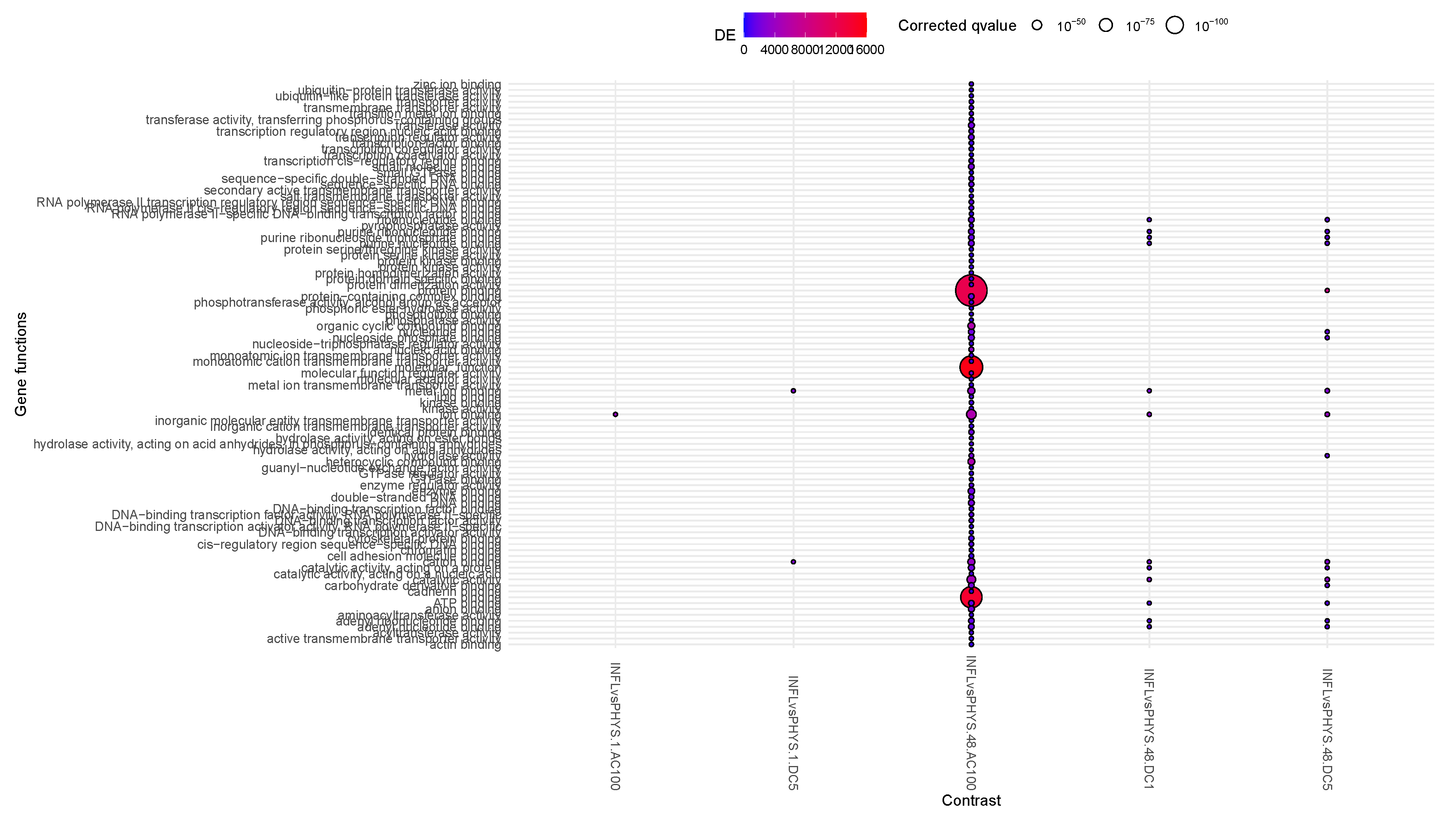

3.4. Question 4: Impact of States on Stimulus

This question aims at clarifying the information gained in Questions 2 and 3, by directly assessing the differential activity occurring in PHYS versus INFL.

The differential effect of AC100 is striking and indicates how in the long term (48h), this stimulus preserves the already observed transmembrane transporter activity difference observed between INFL and PHYS in the absence of stimuli (Question 1). Further, AC100 enhances molecular functions activation and binding, the latter being elicited also at a milder level by DC1-5. Conversely, no enrichment is visible for AC10, indicating that the differences between PHYS and INFL at in the absence of stimuli (reduced transmembrane transporter activity) are canceled out, at the methylation level, by AC10, in other words this suggest that AC10 has the ability to restore this transmembrane activity.

3.5. Question 5: Differential Impact of Stimuli on PHYS

This question clarifies Question 2, regarding the differential effects of stimuli on PHYS samples.

When looking at the plot in

Figure 5,

PHYS.48.AC100vsAC10 and, to a minor extent

PHYS.48.DC5vsAC100, increase the catalytic activity in the cells and reduces transmembrane transporter activity. This activity appears to be graded: with AC100, then DC5 and AC10 slowly reducing their differential effects (in other words, DC5 is equivalent to AC10 on PHYS) . DC1 appears to be involved only transiently (1h) in methylation activity.

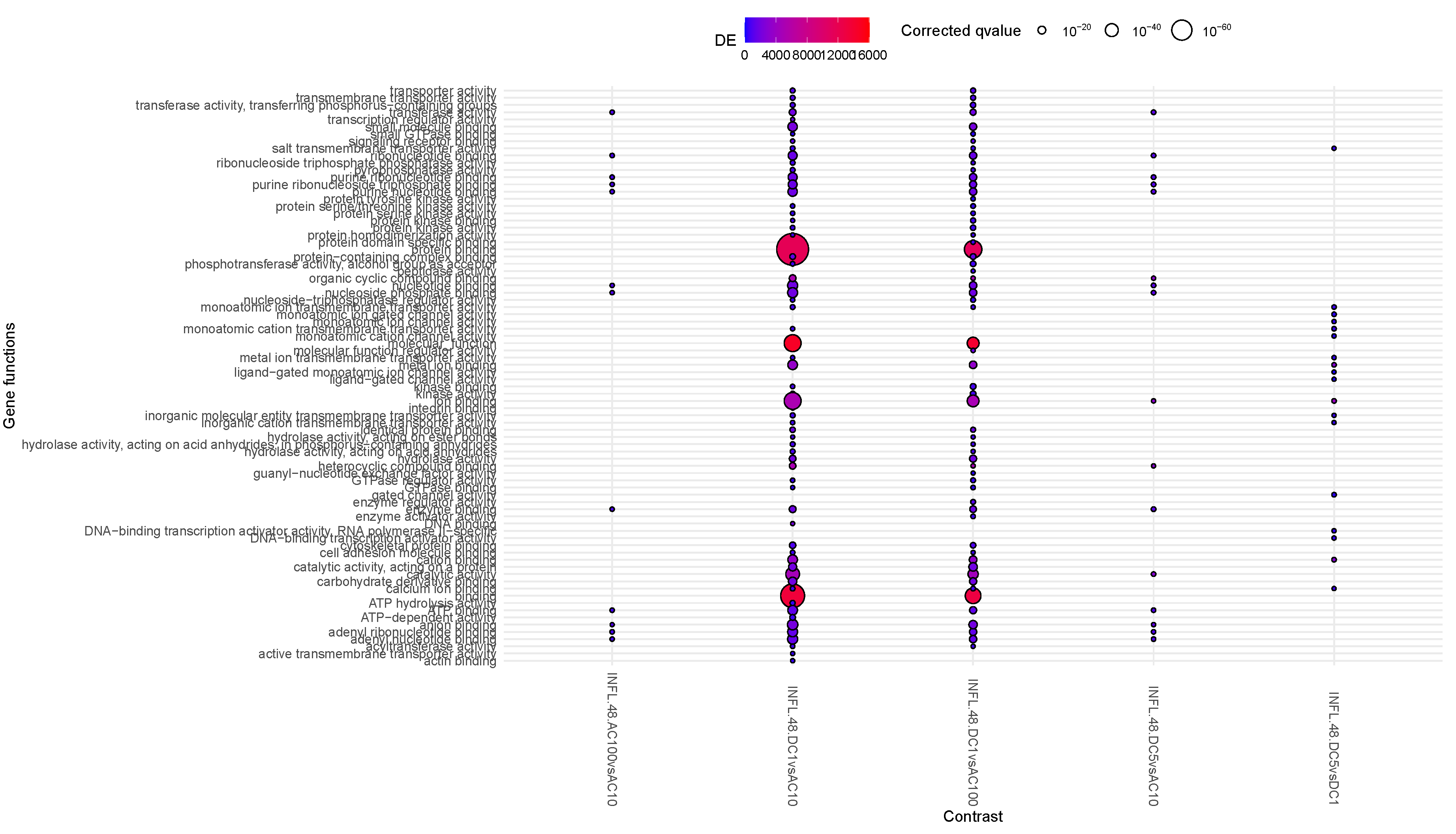

3.6. Question 6: Differential Impact of Stimuli on INFL

Finally, Question 6 deepens the observations of Question 3, on the effects of stimuli on INFL samples.

Early activity (1h) appears to be non-differential, i.e. all stimuli elicit the same type of activation, or no early genes are involved. Conversely, in the long term, several differences are visible. From the observation drawn in Question 3, the visible effects of ACs provoke a shared enhancement of ion binding, which is not differential, however, differences in intensity and the differential transmembrane vs translational activity turn out to present a significant difference in purine binding, reduced in AC100 (INFL48AC100vsAC10). Conversely, voltage impacts on metal ion binding and transmembrane transportation (INFL48DC5vsDC1). Finally, DC1 vs any AC appears to elicit molecular functions activity via protein binding and transporter activity, and reduced purine binding more effectively at 10Hz than 100Hz, where we see a mildly reduced set of enriched functions. This is even more pronounced at 5V DC, which presents no differential activity when compared to AC100, and the reduced purine binding in AC10 (INFL48DC5vsAC10). Overall purine binding appears to represent the core of the activity of AC10.

4. Conclusions

We complete with this work our first systematic exploration of the molecular landscape affected by ES in inflamed conditions. Despite the clear limits of our model, of the number of stimuli, we retain form this work that ES is a versatile tool, able to elicit a variety of effects that are time, state (inflamed or not), modulation (direct or alternate current) and voltage intensity dependent. While this offers additional and unprecedented information on the effects of ES, more detailed mechanistic insights are needed to accelerate the potential for translation. Importantly, our result confirms that caution in the application of ES should be taken, given the very diverse effects obtained. Finally, we wish to highlight that while the simplicity of our construct represents a limit in the translation of the result, it also clearly highlights how ES has an impact on basic and highly conserved mechanisms that are unrelated to the autonomic nervous system, and which should be taken into consideration. We hope that this first overview will trigger more complete and yet systematic analyses to better elucidate the potential and limitations of such approaches for the greatest benefit of patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Methylage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N., L.N and F.F.; methodology C.N., L.N, F.F., C.A. and D.L.; formal analysis, B.D.P., S.V., A.P.; data curation S.D.M, M.D, T.G; writing original draft preparation, review and editing C.N., T.G. and B.D.P; visualization, C.N. and B.D.P; supervision, C.N., L.N., F.F; project administration, C.N., L.N., F.F, D.L.; funding acquisition, C.N., L.T., L.N. and F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CronXCov Fast Track covid-19 call Area Park Trieste

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Methylomic data are available at Gene expression Omnibus with ID GSE280243.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rabbani, M.; Rahman, E.; Powner, M.B.; Triantis, I.F. Making sense of electrical stimulation: a meta-analysis for wound healing. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2024, 52, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, D.; Farmer, D.G.; Yao, S.T. The splanchnic anti-inflammatory pathway: could it be the efferent arm of the inflammatory reflex? Experimental physiology 2016, 101, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Alleyne, G. Recognizing noncommunicable diseases as a global health security threat. Bull World Health Organ 2018, 96, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietro, B.; Villata, S.; Dal MOnego, S.; Degasperi, M.; Ghini, V.; Guarnieri, T.; Plaksienko, A.; Liu, Y.; Pecchioli, V.; Manni, L.; et al. Differential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Electrostimulation in a Standardized Setting. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lena, P.; Sala, C.; Nardini, C. Evaluation of different computational methods for DNA methylation-based biological age. Brief Bioinform 2022, 23, bbac274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wong, A.; Kuh, D.; Paul, D.S.; Rakyan, V.K.; Leslie, R.D.; Zheng, S.C.; Widschwendter, M.; Beck, S.; Teschendorff, A.E. Correlation of an epigenetic mitotic clock with cancer risk. Genome Biology 2016, 17, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Morris, T.J.; Webster, A.P.; Yang, Z.; Beck, S.; Feber, A.; Teschendorff, A.E. ChAMP: updated methylation analysis pipeline for Illumina BeadChips. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3982–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipson, B.; Maksimovic, J. missMethyl: Analysing Illumina HumanMethylation BeadChip Data. dim (Mval) 2022, 1, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Durso, D.F.; Bacalini, M.G.; Sala, C.; Pirazzini, C.; Marasco, E.; Bonafé, M.; do Valle, Í.F.; Gentilini, D.; Castellani, G.; Faria, A.M.C.; et al. Acceleration of leukocytes’ epigenetic age as an early tumor and sex-specific marker of breast and colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23237–23245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 1420–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).