Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The RadonEye Monitor

Calibration

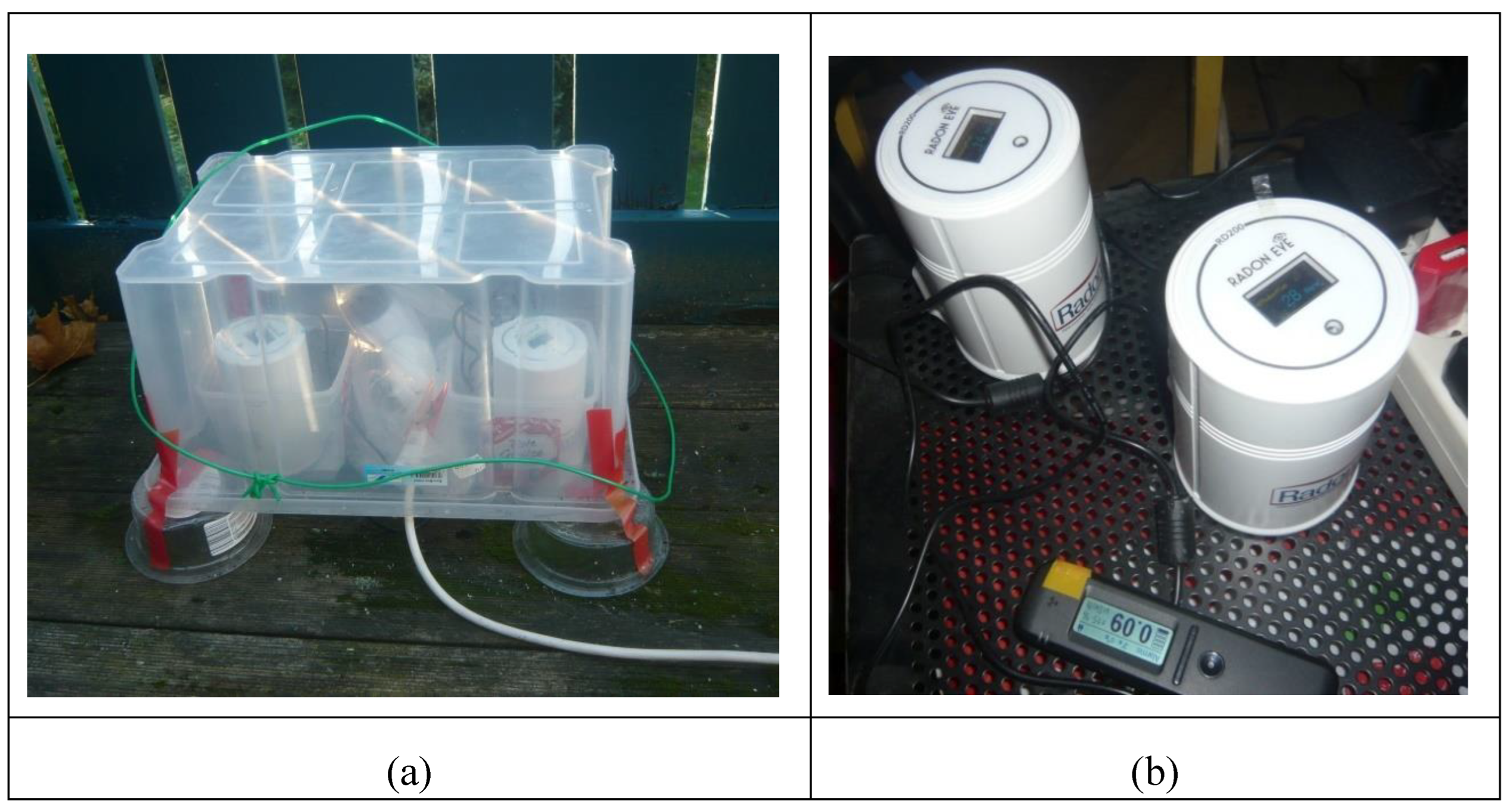

2.2. Parallel Exposure

2.3. Response to Thoron Exposure

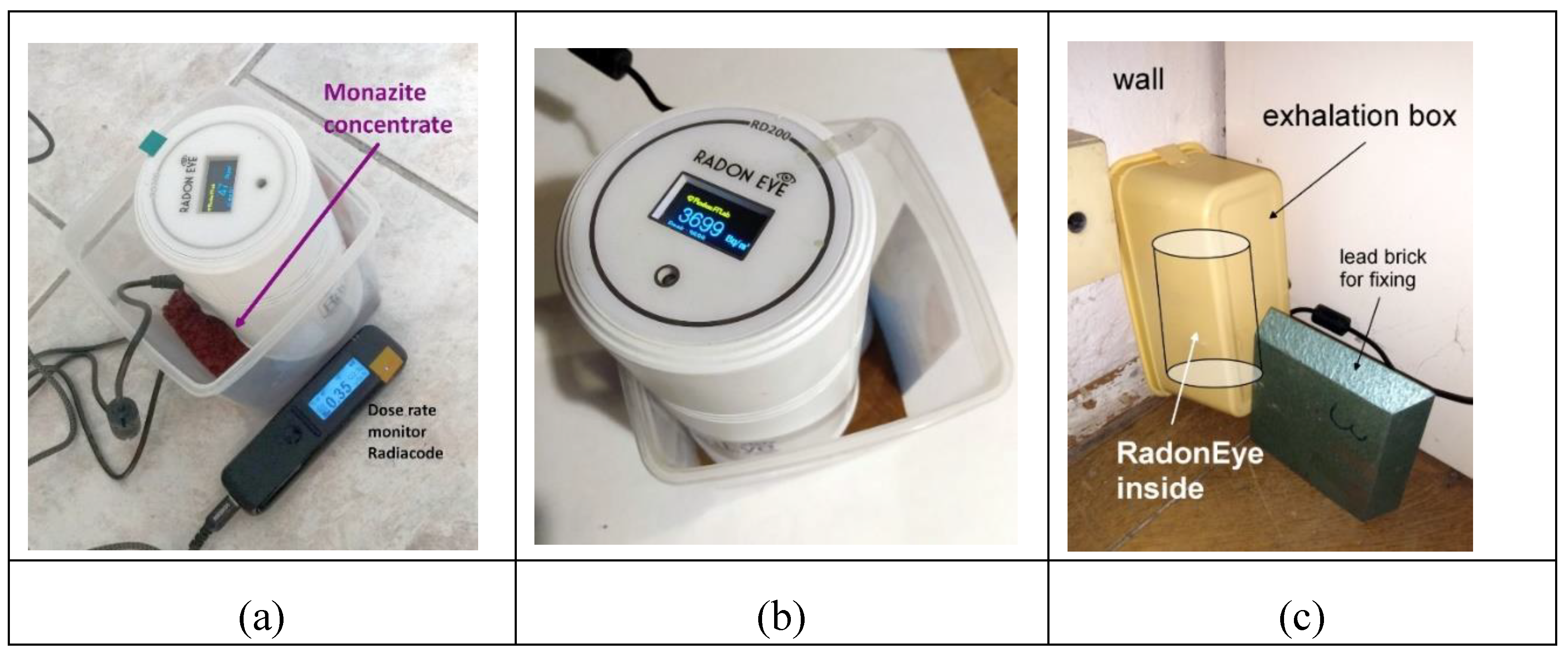

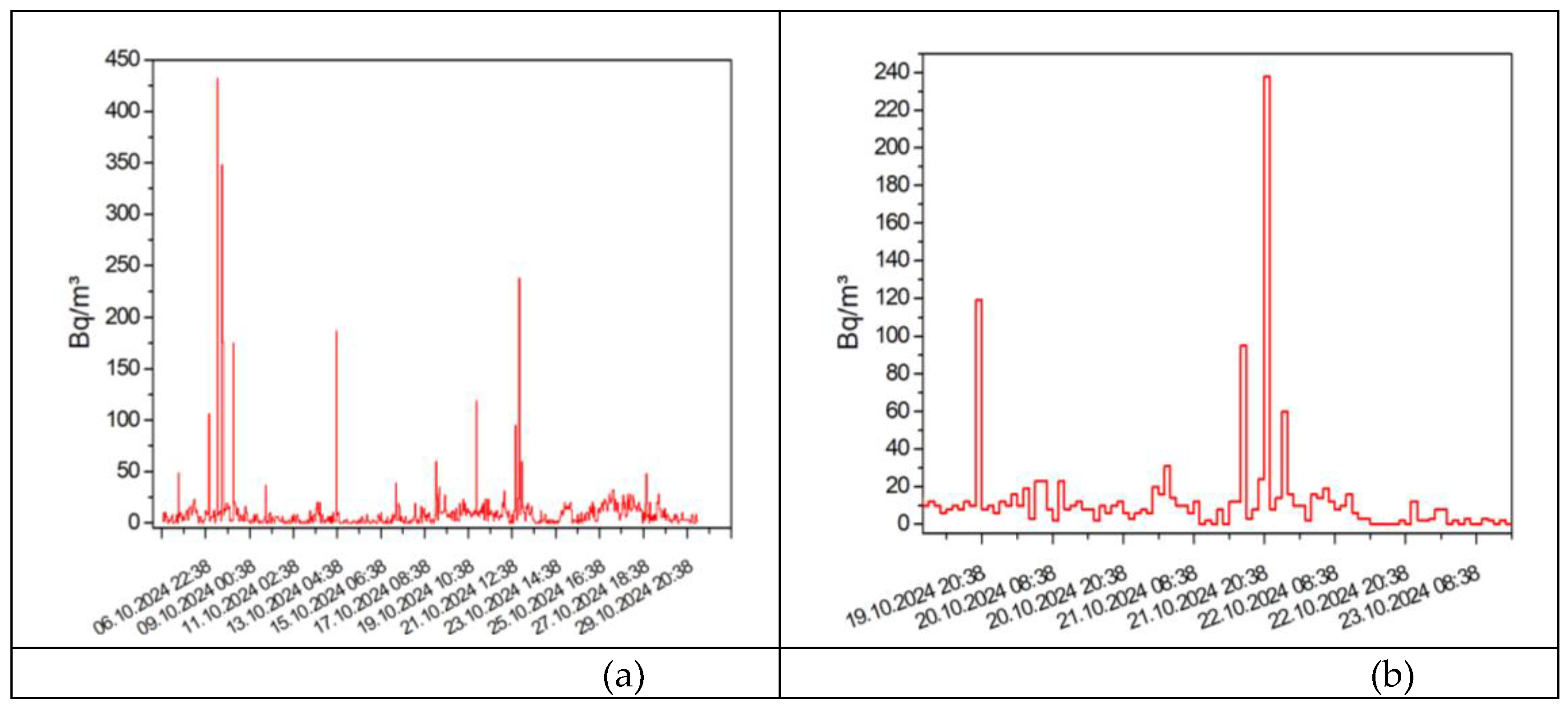

2.4. Anomalies

2.5. Correlation Between Parallel Time Series

2.6. Software

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Deviation from Nominal Calibration

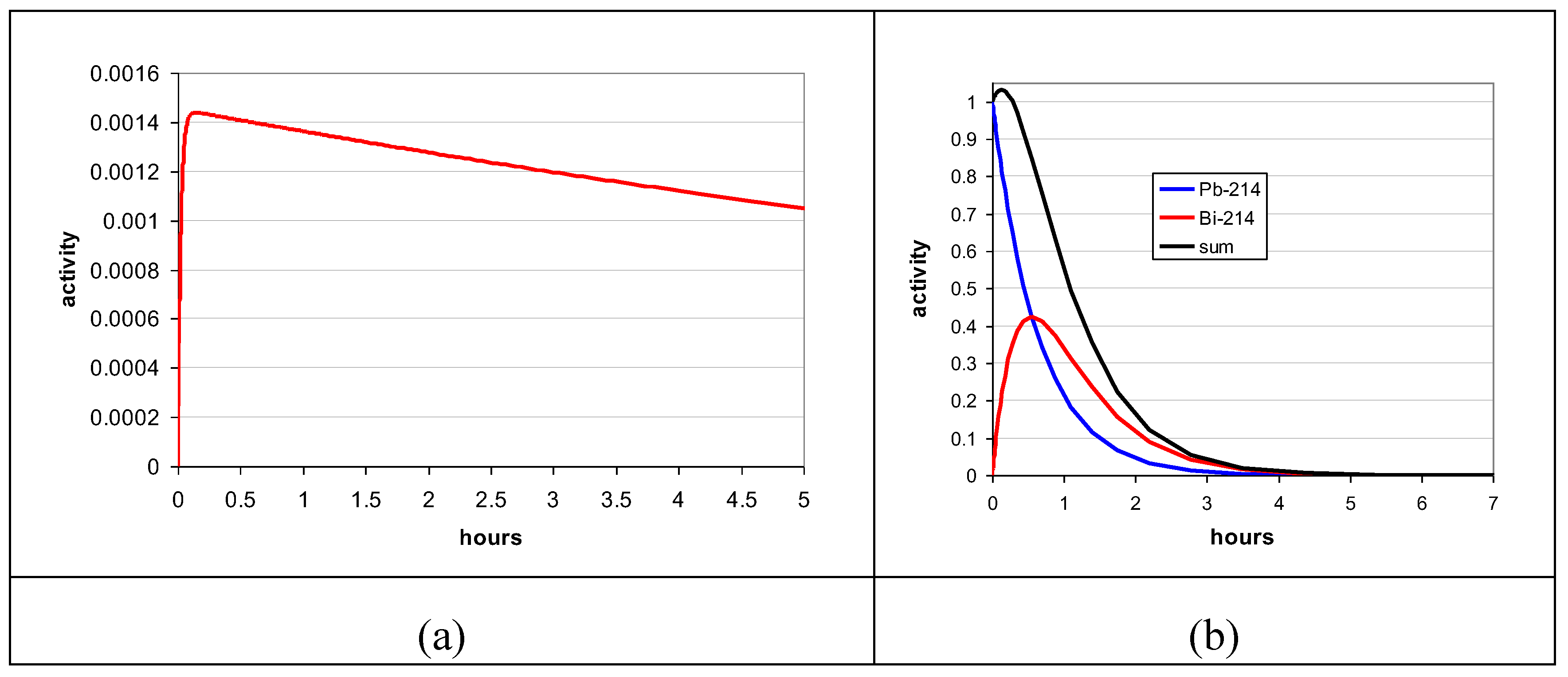

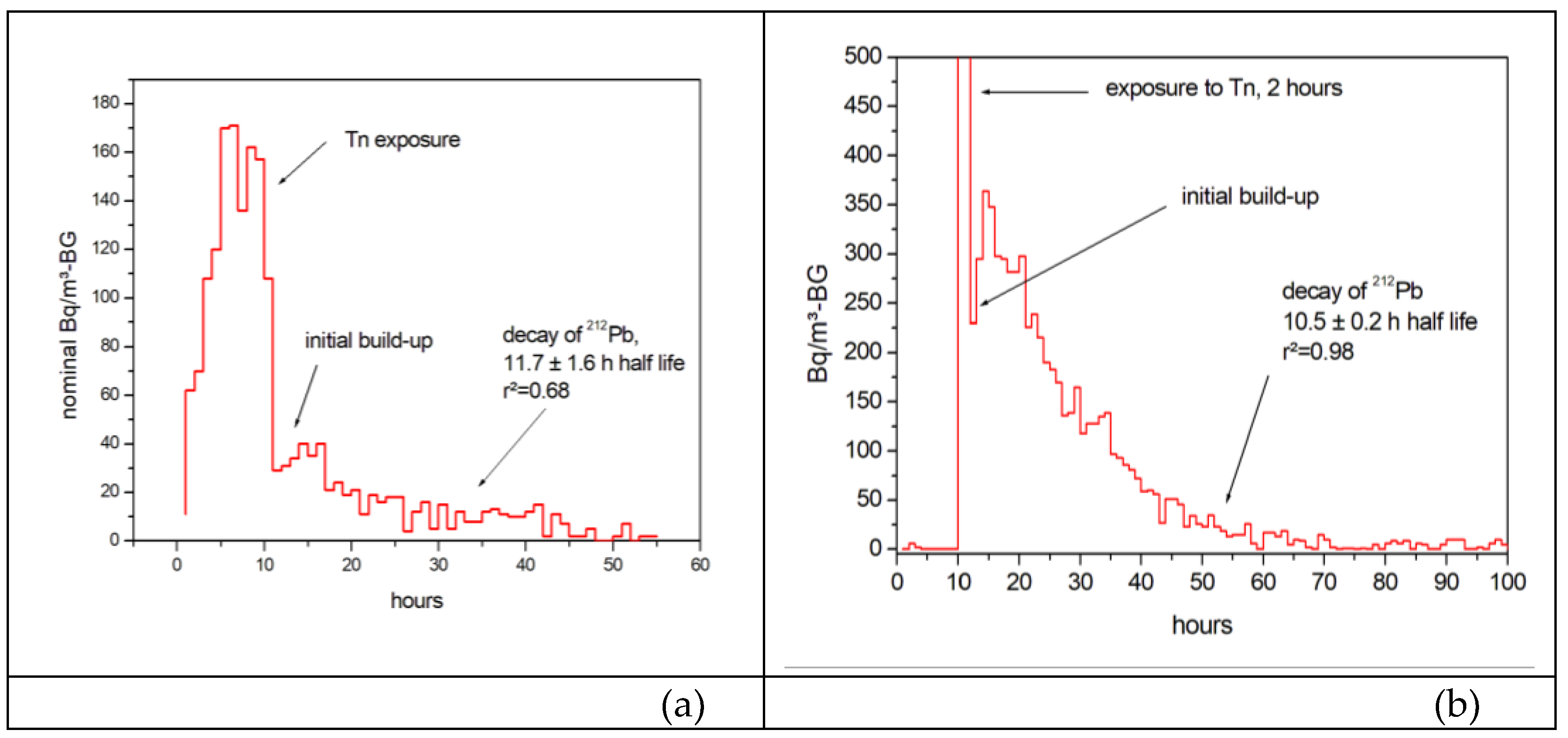

3.2. Thoron Effect on the RadonEye

3.2.1. Experiments Tn-1 and Tn-2

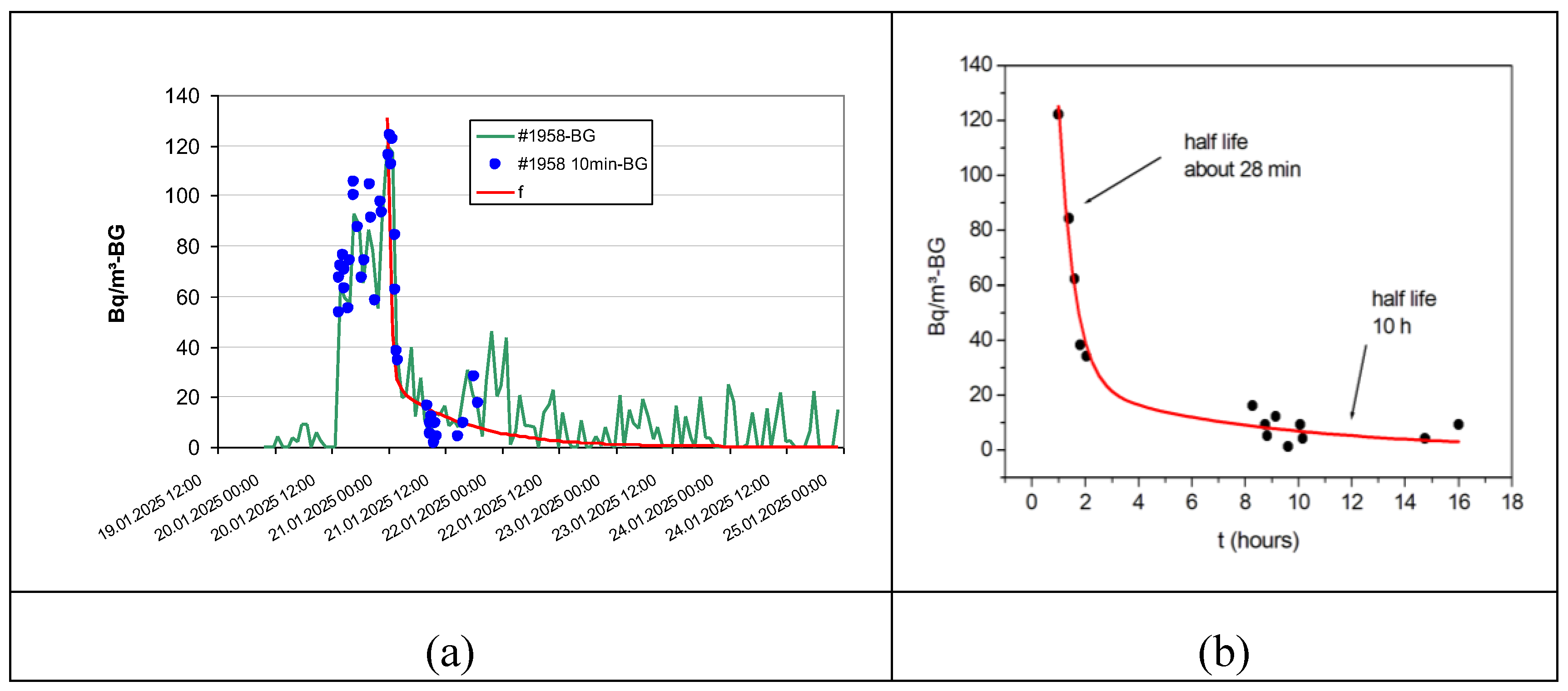

3.2.2. Experiment Tn-3

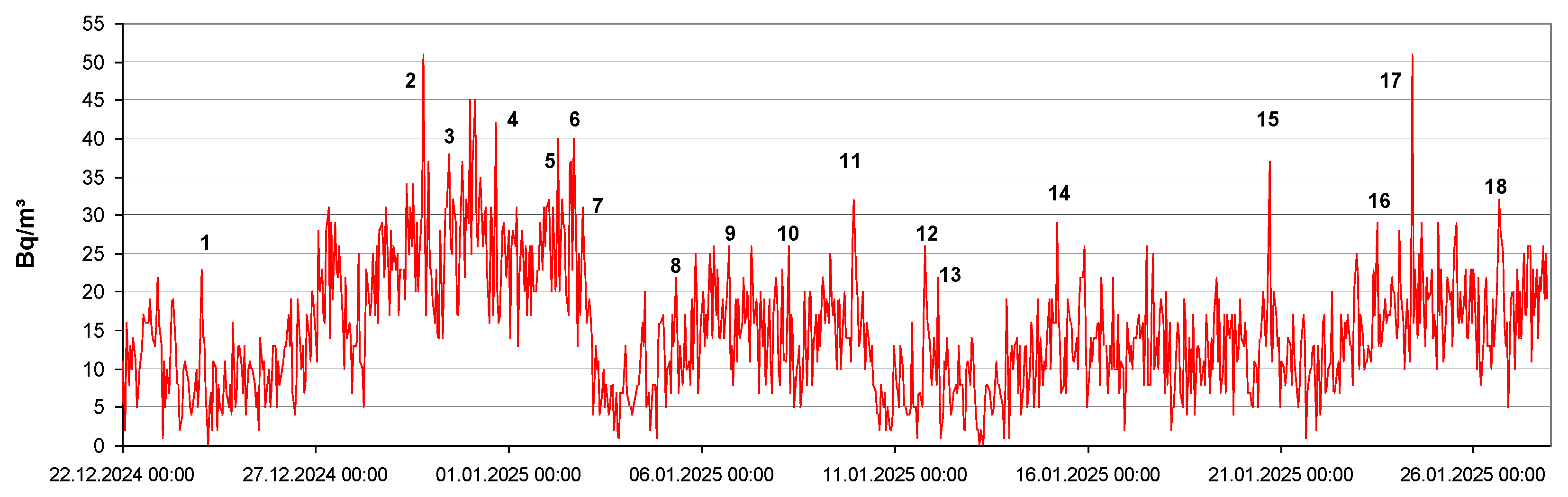

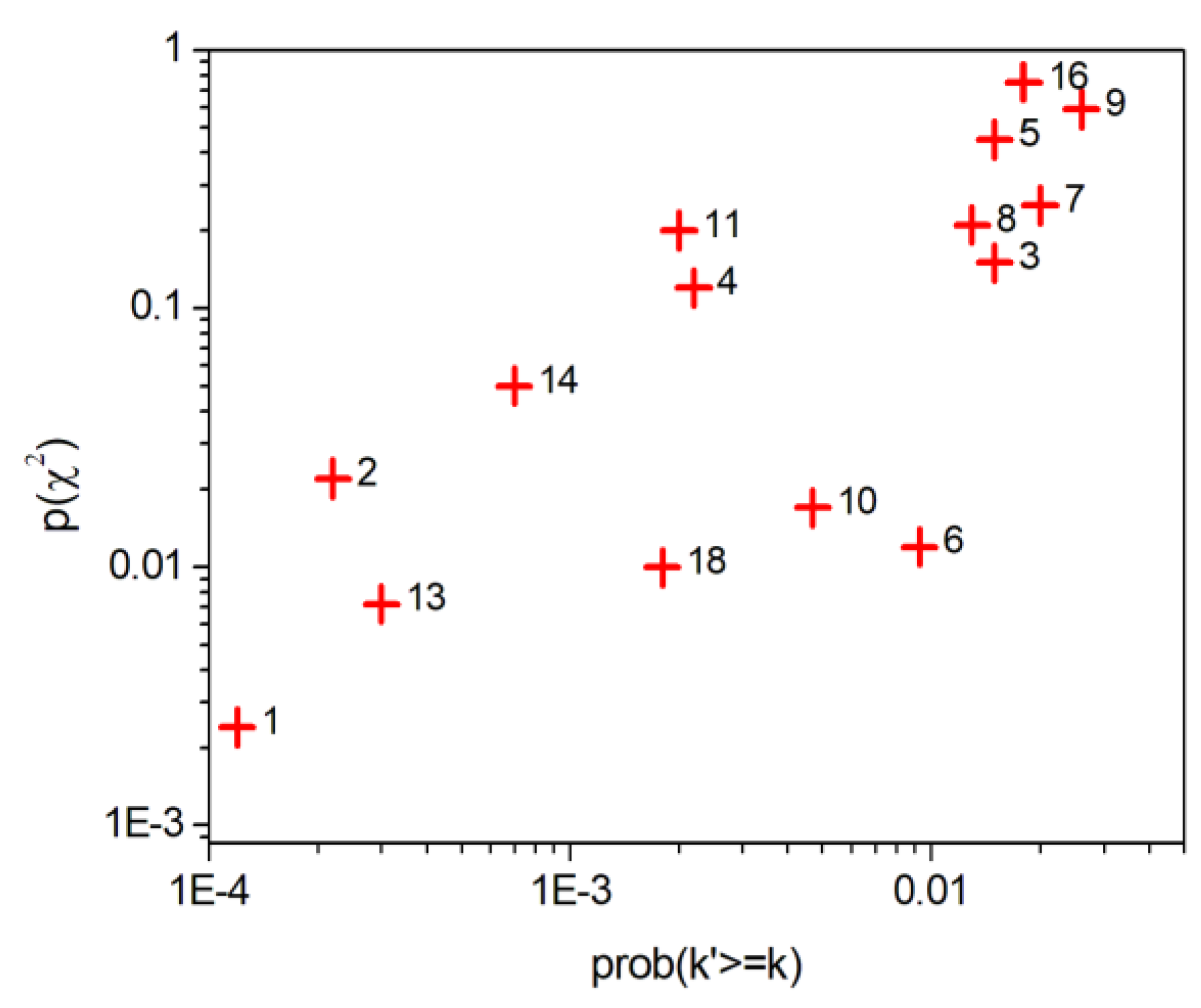

3.3. Anomalies

3.3.1. Series RE22207111958

3.3.2. Series GJ17RE000076

3.4. Missing Concentration Values

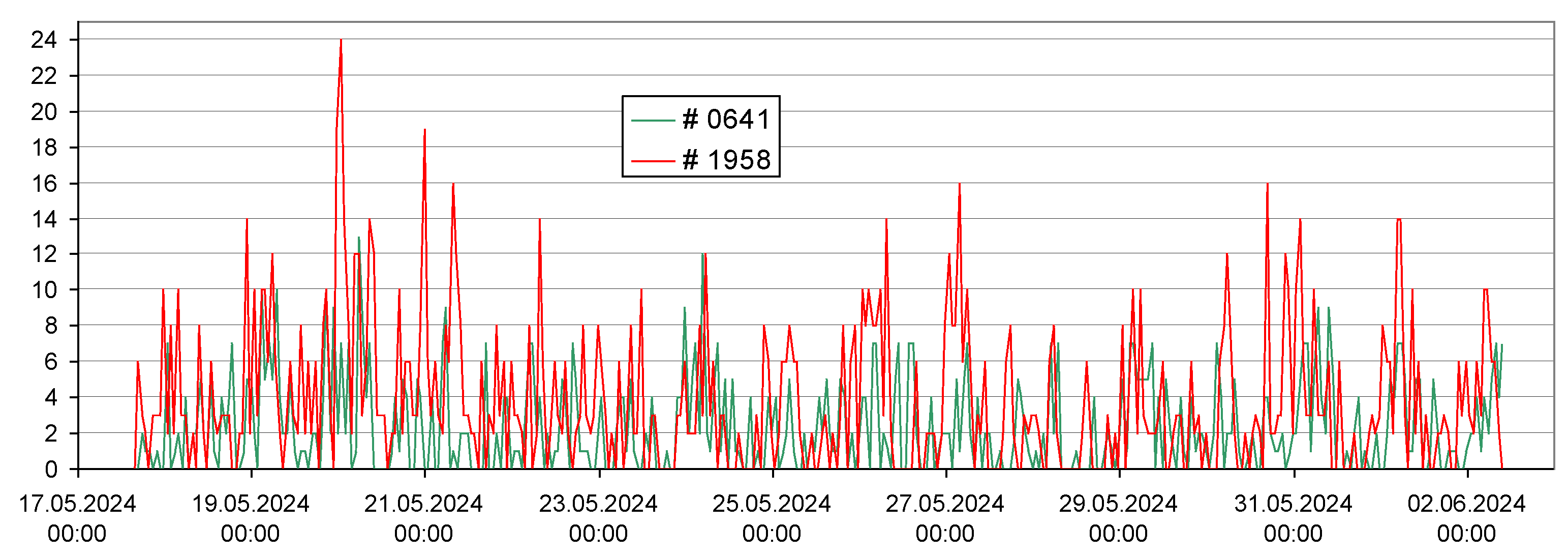

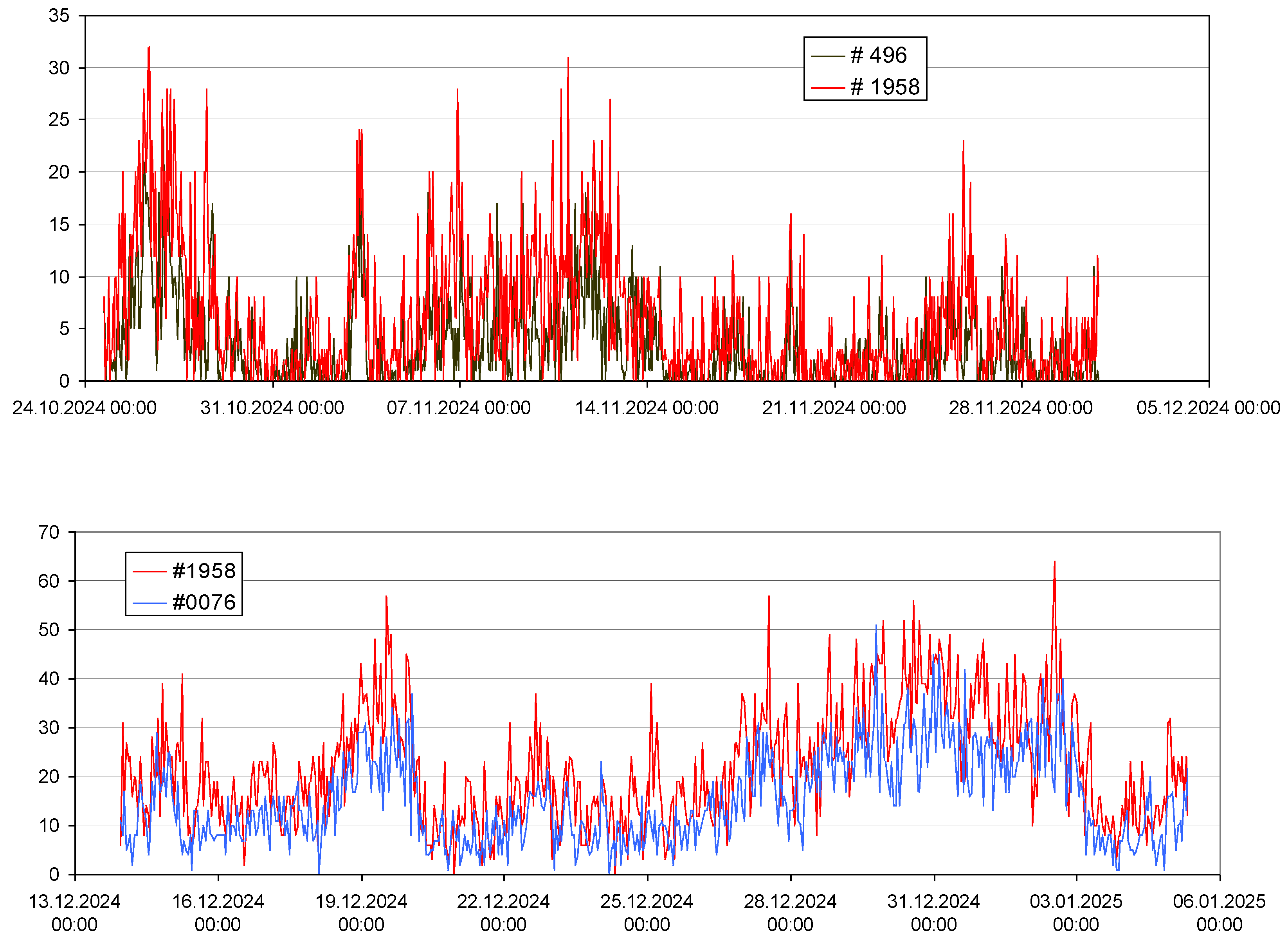

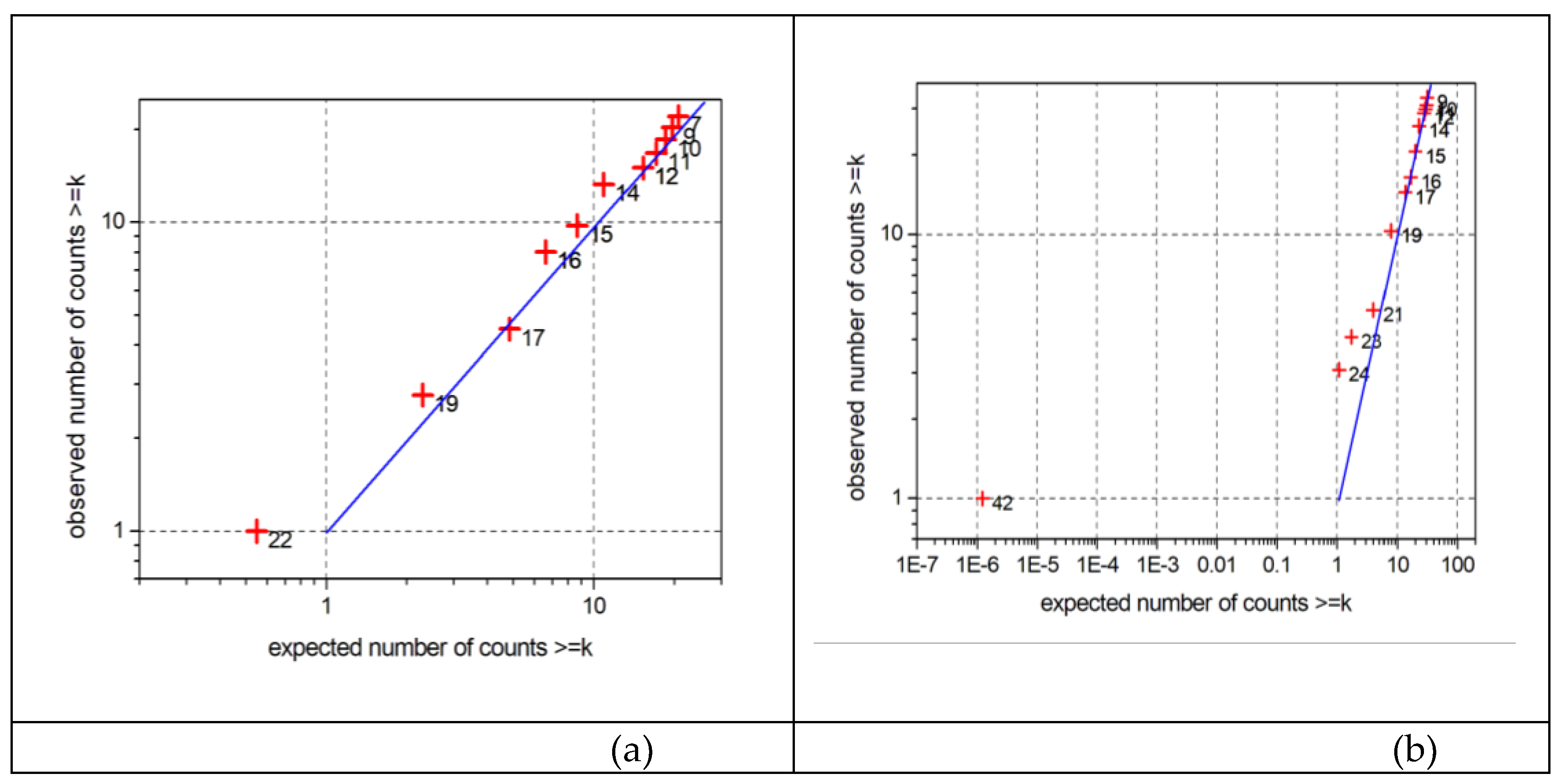

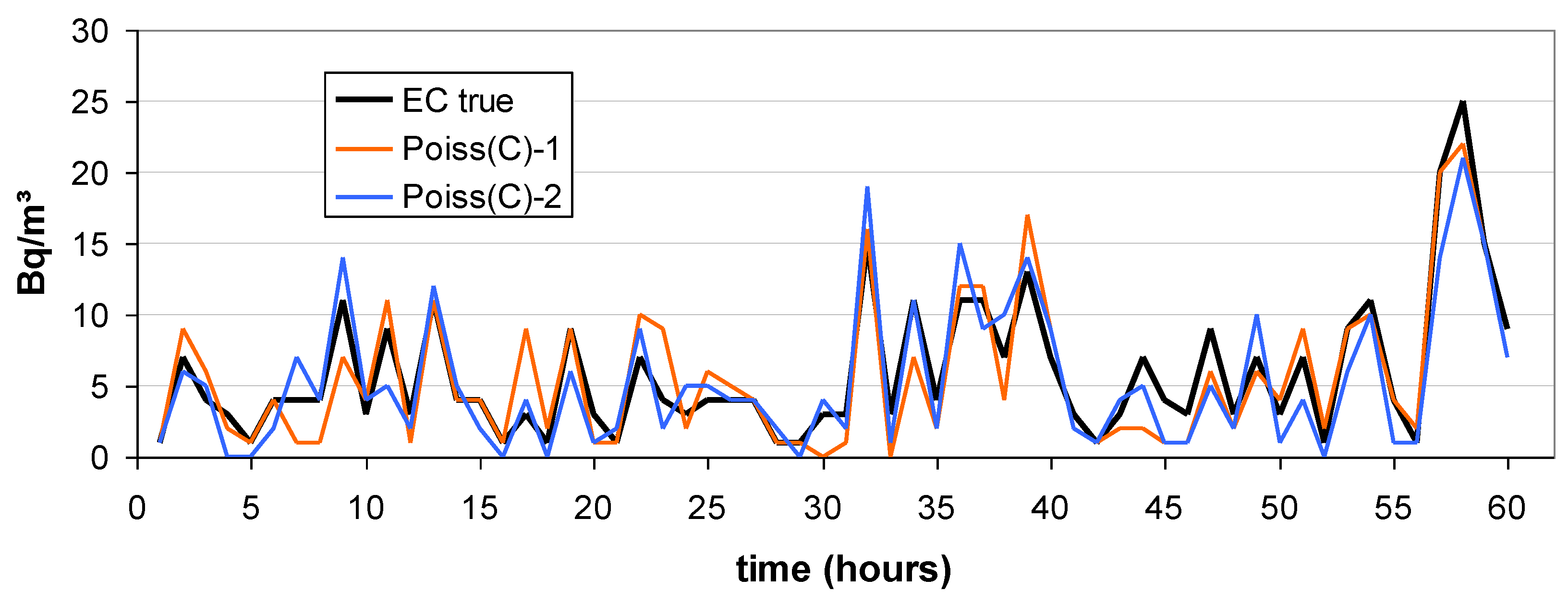

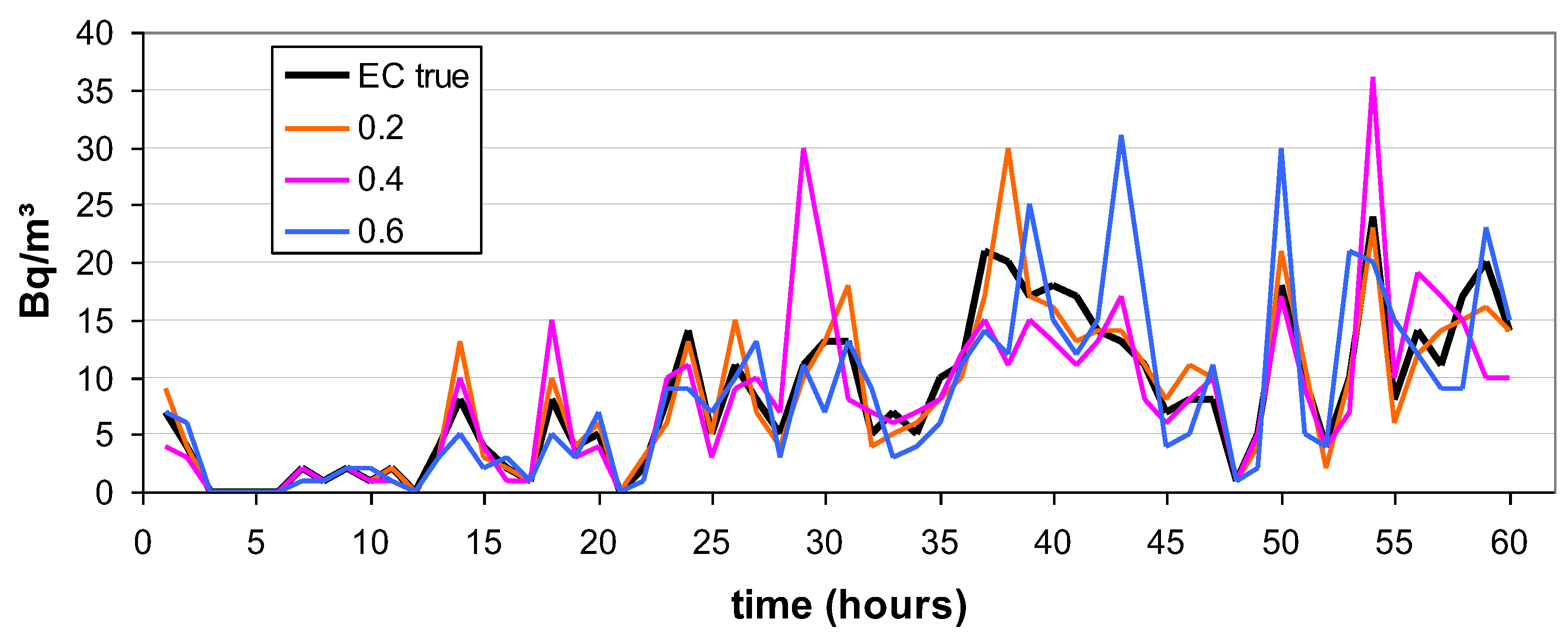

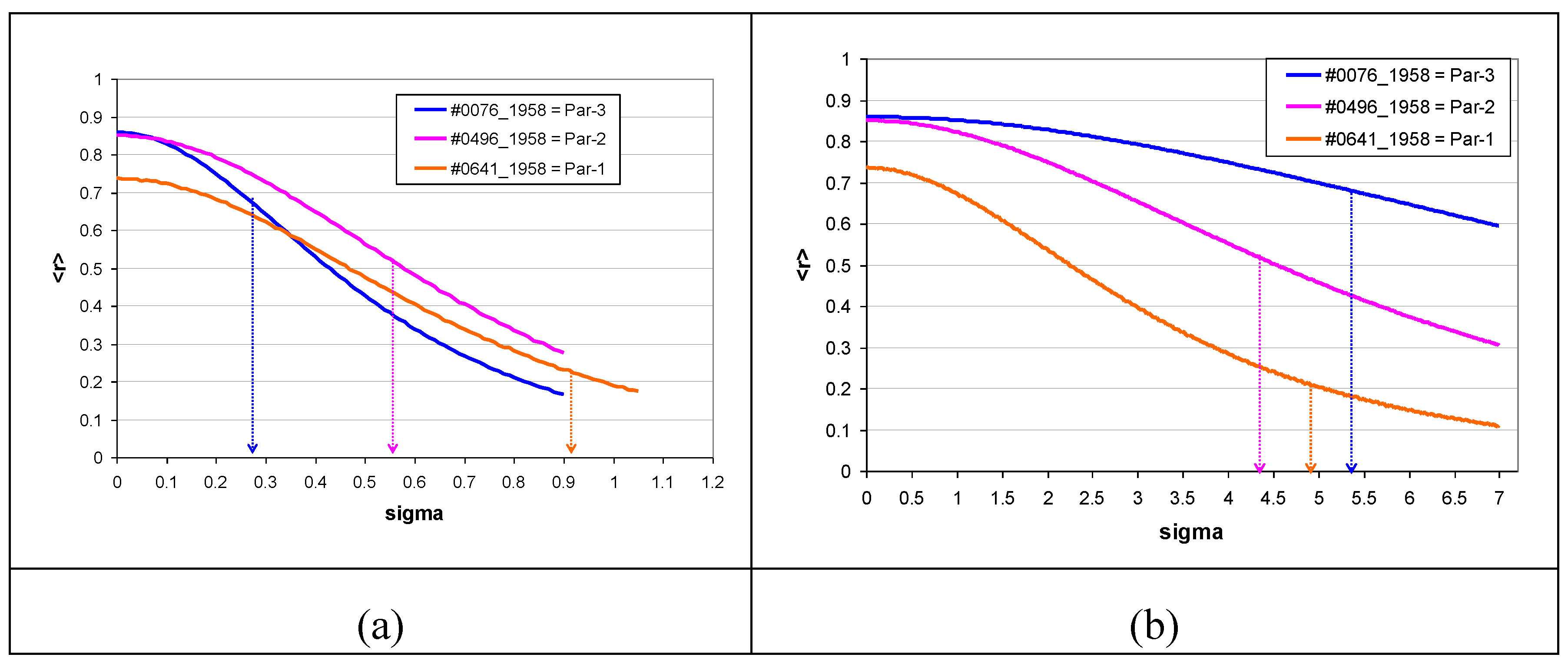

3.5. Correlation Between Parallel Time Series

3.5.1. Analysis 1

3.5.2. Analysis 2

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Calibration Issues

4.2. Thoron

4.3. Anomalies

4.4. Statistical Issues, Missing Concentration Values

4.5. Citizen Science and Professional Use

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajo Zeeb, Ferid Shannoun (eds): WHO handbook on indoor radon: a public health perspective, 2009. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547673 (accessed 14.1.2025).

- Vohland, K.; Landzandstra, A.; Ceccaroni, L.; Lemmens, R.; Perelló, J.; Ponti, M.; Samson, R.; Wagenknecht, K. (Eds.) The Science of Citizen Science; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bossew P., Benà E., Chambers S., Janik M. Analysis of outdoor and indoor radon concentration time series recorded with RadonEye monitors. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1468. [CrossRef]

- Radon FTLab (no year): http://radonftlab.com/ (accessed 14.1.2025).

- Radon Eye operation manual, Model RD 200, no year. https://merona.blob.core.windows.net/radonftlab-web/20220404_RadonEye_%EC%82%AC%EC%9A%A9%EC%9E%90%EC%84%A4%EB%AA%85%EC%84%9C(%EC%98%81%EB%AC%B8).pdf (accessed 14.1.2025).

- No title, no year: https://www.radonshop.com/mediafiles/Anleitungen/Radon/FTLab_RadonEye-RD200/FTLab_RadonEye_ManualEN.pdf (accessed 20.3.2025).

- Radon-220 (Thoron) decay chain (https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/69157-radon-220-thoron-decay-chain ), MATLAB Central File Exchange. (Accessed 11.1.2025).

- EPA, Radionuclide Decay Chain (n.y.): https://epa-prgs.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/radionuclides/chain.pl (accessed 21.1.2025).

- Bossew P., Kuča P., Helebrant J. True and spurious anomalies in ambient dose rate monitoring. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 2023, 199(18), 2183–2188; [CrossRef]

- Devroye, Luc (1986). “Discrete Univariate Distributions”. https://luc.devroye.org/chapter_ten.pdf (accessed 20.1.2025).

- Hammer, Ø., Harper, D.A.T., Ryan, P.D. 2001. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 2024, 4(1): 9pp. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm. Download: https://www.nhm.uio.no/english/research/resources/past/ (accessed 20.3.2025).

- Beck T., Foerster E., Biel M., Feige S. Measurement Performance of Electronic Radon Monitors. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1180. [CrossRef]

- Tsapalov, A.; Kovler, K.; Bossew, P. Strategy and Metrological Support for Indoor Radon Measurements Using Popular Low-Cost Active Monitors with High and Low Sensitivity. Sensors 2024, 24,4764. [CrossRef]

| Experiment | par-1 | par-2 | par-3 | |||

| Device# | #1958 | #0641 | #1958 | #0496 | #1958 | #0076 |

| Date | 17.5.-2.6.2024 | 24.10.-3.11.2024 | 13.12.2024-5.1.2025 | |||

| n | 379 | 893 | 538 | |||

| AM | 3.8 | 2.4 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 22.1 | 15.4 |

| SD | 4.0 | 2.6 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 11.8 | 9.1 |

| SE | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.39 |

| AM1/AM2 ± SE | 1.58 ± 0.12 | 1.66 ± 0.09 | 1.44 ± 0.05 | |||

| paired test | ||||||

| t | 9.2e-11 | 6.7e-36 | 2.3e-54 | |||

| sign | 2.0e-7 | 1.7e-21 | 8.0e-43 | |||

| Wilcoxon | 6.0e-10 | 2.1e-34 | 8.5e-49 | |||

| unpaired | ||||||

| t(uneq var) | 3.7e-9 | 7.1e-21 | 3.5e-24 | |||

| M-W | 9.6e-7 | 2.2e-16 | 1.2e-21 | |||

| F eq var | 6.9e-18 | 1.9e-33 | 5.2e-9 | |||

| K-S | 1.2e-8 | 4.0e-22 | 1.7e-16 | |||

| A-D | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| correlation | ||||||

| Pearson r | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.67 | |||

| Spearman ρ | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.68 | |||

| event # | date | Rn | cts k | BG (cts) | prob(k’≥k) | p(χ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24.12., 0:48 | 23 | 19 | 6.94 | 1.2e-4 | 0.0024 |

| 2 | 29.12., 18:48 | 51 | 42 | 22.93 | 2.2e-4 | 0.022 |

| 3 | 30.12., 10:48 | 38 | 32 | 21.00 | 0.015 | 0.15 |

| 4 | 31.12., 15:48 | 42 | 35 | 20.50 | 0.0022 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 2.1., 6:48 | 40 | 33 | 21.82 | 0.015 | 0.45 |

| 6 | 2.1., 16:48 | 40 | 33 | 21.00 | 0.0093 | 0.012 |

| 7 | 2.1., 21:48 | 31 | 26 | 16.6 | 0.020 | 0.25 |

| 8 | 5.1., 7:48 | 22 | 19 | 10.67 | 0.013 | 0.21 |

| 9 | 6.1., 16:47 | 26 | 22 | 13.85 | 0.026 | 0.59 |

| 10 | 8.1., 5:47 | 26 | 22 | 11.74 | 0.0047 | 0.017 |

| 11 | 9.1., 22:47 | 32 | 27 | 14.41 | 0.0020 | 0.20 |

| 12 | 11.1., 18:47 | 26 | 22 | 8.09 | 3.9e-5 | 6.0e-6 |

| 13 | 12.1., 2:47 | 22 | 19 | 7.50 | 3.0e-4 | 0.0072 |

| 14 | 15.1., 4:47 | 29 | 24 | 11.33 | 7.0e-4 | 0.050 |

| 15 | 20.1., 16:47 | 37 | 31 | 10.22 | 1.3e-7 | 1.8e-5 |

| 16 | 23.1., 11:47 | 29 | 24 | 14.87 | 0.018 | 0.75 |

| 17 | 24.1., 9:47 | 51 | 42 | 15.87 | 3.8e-8 | 1.2e-4 |

| 18 | 26.1., 15:48 | 32 | 27 | 14.32 | 0.0018 | 0.010 |

| device id. | missing concentration values (Bq/m³) |

|---|---|

| GJ17RE000076 | 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24,... |

| RE22207111958 | 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 18,... |

| HG04RE000641 | 3, 6, 8, 11, 13,... |

| HK01RE000496 | 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, … |

| Experiment | series | 〈r〉 ± SD | empir. r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Par-1 | #0641 | 0.738 ± 0.0235 | 0.22 |

| #1958 | 0.735 ± 0.025 | ||

| Par-2 | #0496 | 0.851 ± 0.010 | 0.51 |

| #1958 | 0.821 ± 0.011 | ||

| Par-3 | #0076 | 0.860 ± 0.009 | 0.68 |

| #1958 | 0.829 ± 0.015 | ||

| rnd-1 | 0.514 ± 0.030 | ||

| rnd-2 | 0.703 ± 0.020 |

| Experiment | series | σopt | empir. r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| model LN | model SQR+, b=0.5 | |||

| Par-1 | #0641 | 0.92 | 4.76 | 0.22 |

| #1958 | 0.92 | 4.89 | ||

| Par-2 | #0496 | 0.56 | 4.42 | 0.51 |

| #1958 | 0.52 | 3.80 | ||

| Par-3 | #0076 | 0.26 | 5.54 | 0.67 |

| #1958 | 0.22 | 4.58 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).