Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

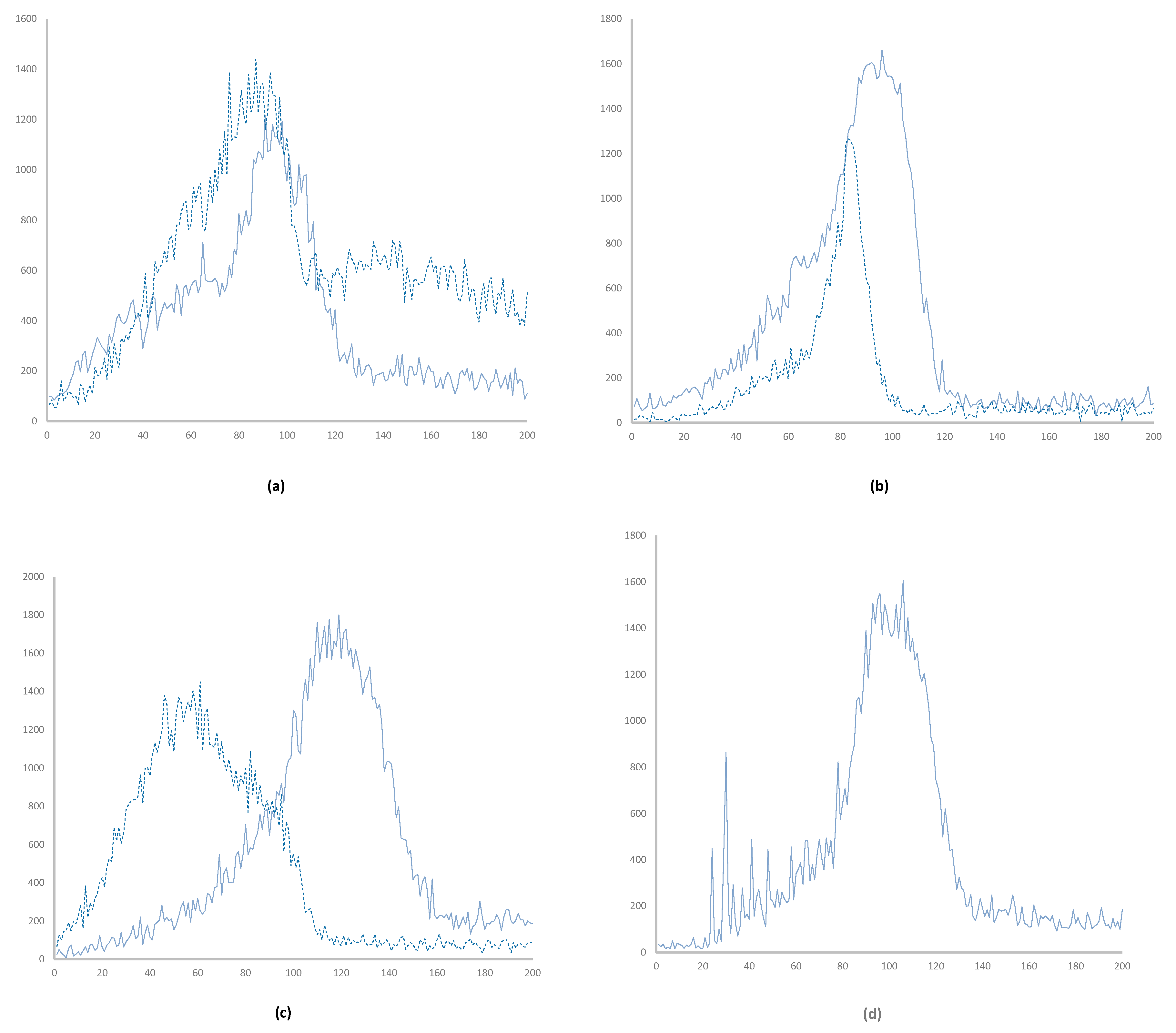

- Class A Low (Figure 2a) is characterized by high TL signal at low temperatures. Possible reasons causing this anomaly include: organic (usually carbon) contamination of the Teflon cover on the TLD element, from user’s dirty fingers, aging of Teflon foils, which causes them to split from TLD element and to transfer heat less efficiently to the TLD element, nitrogen flow problems during heating of the TLD elements by hot-gas, and residual radiation from a prior exposure to a relatively high dose.

- -

- Class A High (Figure 2a) is characterized by high TL signal at high temperatures. Some possible reasons causing this anomaly include: pre- and post-irradiation annealing procedures, TLD heating rate issues (GPs move to higher temperatures as the heating rate increases), and spectral response of either the photocathode or other optics such as IR filters.

- -

- Class B Wide (Figure 2b) is characterized by wide GPs compared to normal GPs. Some possible reasons for this anomaly include: TLD batch characteristics, the position of the TLD element between Teflon foils that was set in the factory, aging of Teflon foils, which causes them to split from TLD element and to transfer heat less efficiently to the TLD element.

- -

- Class D Spikes (Figure 2d) is characterized by spikes over the GC. These spikes may be caused by static electricity (especially in TLD readers, which are located in extremely low humidity areas), light emanates from burning particles, which arise from contamination on the TLD sample surface or on the Teflon foils from either dust or oily fingerprints, electrical network interruptions, or reader electronic interferences.

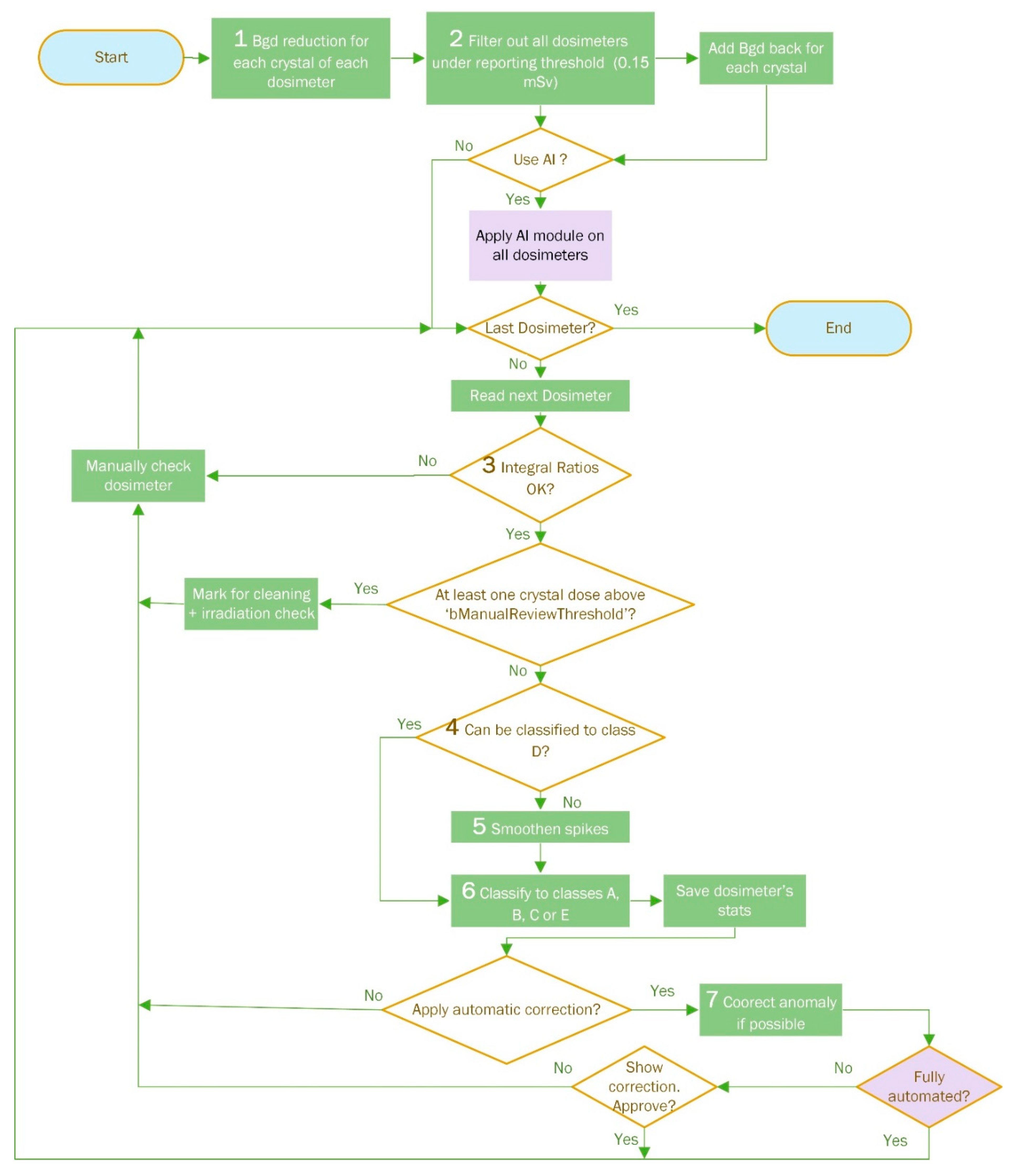

TLDetect SW & Pipeline

2. Materials and Methods

Detailed Algorithm Stages Review

- i.

- Background reduction

- ii.

- Filtering out low dose dosimeters

- iii.

- AI Filter for normal GCs

- iv.

- Integral ratios filter

- v.

- Class D classification smoothening

- vi.

- Smoothening

- vii.

- Classify GC to either Class A, B, C or E

- a.

- Class A classification

- b.

- Class C classification

- c.

- Class B classification

- d.

- Class E classification

- viii.

- Anomaly correction

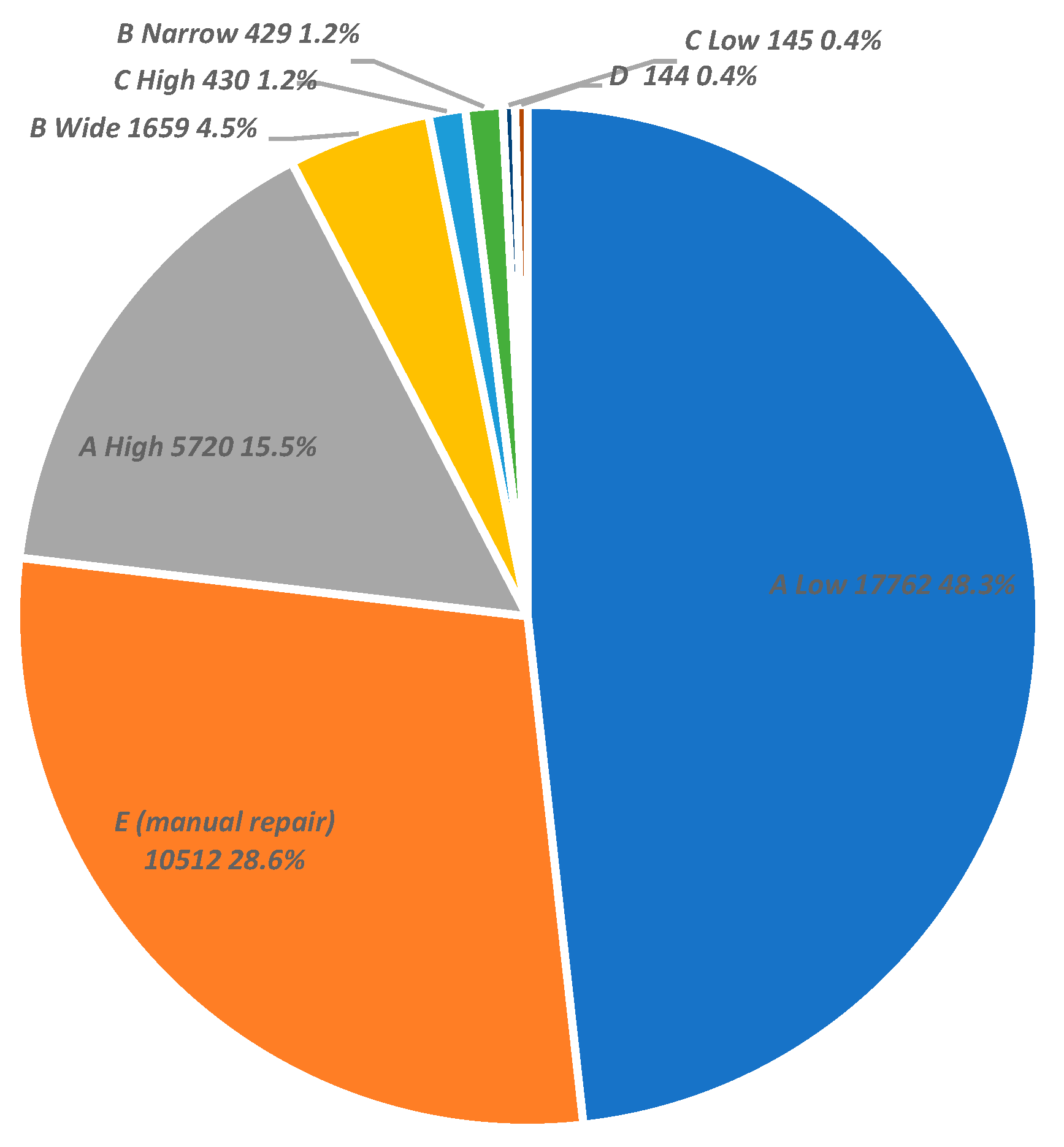

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Business Intelligence Tool

3.2. Results

References

- Occupational radiation exposure among diagnostic radiology workers in the Saudi ministry of health hospitals and medical centers: a five-year national retrospective study. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. (2021), p. 101249.

- Assessment of occupational exposure of radiation workers at a tertiary hospital in Anhui province, China, during 2013-18. Radiaion Protection Dosimetry, 190 (3) (2020), 237-242.

- Baudin C, Vacquier B et Al. Occupational exposure to ionizing radiation in medical staff: trends during the 2009-2019 period in a multicentric study. Eur Radiol. 2023 Aug;33(8):5675-5684. [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Stewart, K.S. , Fontanarosa, D., Malacova, E. et al. A comparison of patient dose and occupational eye dose to the operator and nursing staff during transcatheter cardiac and endovascular procedures. Sci Rep 13, 2391 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Richardson D B, Leuraud K, Laurier D, Gillies M, Haylock R, Kelly-Reif K et al. Cancer mortality after low dose exposure to ionising radiation in workers in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (INWORKS): cohort study BMJ 2023; 382 :e074520. [CrossRef]

- Hiba Omer, H. Salah, N. Tamam, Omer Mahgoub, A. Sulieman, Rufida Ahmed, M. Abuzaid, Ibrahim E. Saad, Kholoud S. Almogren, D.A. Bradley, Assessment of occupational exposure from PET and PET/CT scanning in Saudi Arabia, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, Volume 204, 2023, 110642, ISSN 0969-806X. [CrossRef]

- Boice, J. D. , Cohen, S. S., Mumma, M. T., Howard, S. C., Yoder, R. C., & Dauer, L. T. (2022). Mortality among medical radiation workers in the United States, 1965–2016. International Journal of Radiation Biology, 99(2), 183–207. [CrossRef]

- Cha ES, Zablotska LB, Bang YJ, et al. Occupational radiation exposure and morbidity of circulatory disease among diagnostic medical radiation workers in South Korea. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020;77:752-760.

- M. Alkhorayef, Fareed H. Mayhoub, Hassan Salah, A. Sulieman, H.I. Al-Mohammed, M. Almuwannis, C. Kappas, D.A. Bradley, Assessment of occupational exposure and radiation risks in nuclear medicine departments, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, Volume 170, 2020, 108529, ISSN 0969-806X. [CrossRef]

- Jinghua Zhou, Wei Li, Jun Deng, Kui Li, Jing Jin, Huadong Zhang, Trend and distribution analysis of occupational radiation exposure among medical practices in Chongqing, China (2008–2020), Radiation Protection Dosimetry, Volume 199, Issue 17, October 2023, Pages 2083–2088. [CrossRef]

- Enrique Garcia-Sayan, Renuka Jain, Priscilla Wessly, G. Burkhard Mackensen, Brianna Johnson, Nishath Quader, Radiation Exposure to the Interventional Echocardiographers and Sonographers: A Call to Action. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, Volume 37, Issue 7, 2024, Pages 698-705, ISSN 0894-7317. [CrossRef]

- Azizova, T.V. , Bannikova, M.V., Briks, K.V. et al. Incidence risks for subtypes of heart diseases in a Russian cohort of Mayak Production Association nuclear workers. Radiat Environ Biophys 2023, 62, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikezawa, K. , Hayashi, S., Takenaka, M. et al. Occupational radiation exposure to the lens of the eyes and its protection during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Sci Rep 13, 7824 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj, A.N. , Lagarde, C.S., 2004. Glow curve evaluation in routine personal dosimetry. Health Phys. 86.

- Horowitz, Y.S. , Moscovitch, M., 2013. Highlights and pitfalls of 20 years of application of computerised glow curve analysis to thermoluminescence research and dosimetry. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 153, 1–22.

- Horowitz, Y.S. , Yossian, D., 1995a. Computerized glow curve deconvolution applied to the analysis of the kinetics of peak 5 in LiF: Mg,Ti (TLD-100). J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 28, 1495.

- Horowitz, Y.S. , Yossian, D., 1995b. Computerised glow curve deconvolution: application to thermoluminescence dosimetry. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 60. Horowitz, Y.S., Oster, L., Datz, H., 2007. The thermoluminescence dose–response and other characteristics of the high-temperature TL in LiF: Mg,Ti (TLD-100). Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 124, 191–205.

- Karmakar, M. , Bhattacharyya, S., Sarkar, A., Mazumdar, P.S., Singh, S.D., 2017. Analysis of thermoluminescence glow curves using derivatives of different orders. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 175, 493–502.

- A.M. Sadek, M.A. Farag, A.I. Abd El-Hafez, G. Kitis. TL-SDA: A designed toolkit for the deconvolution analysis of thermoluminescence glow curves, Applied Radiation and Isotopes, Volume 206, 2024, 111202, ISSN 0969-8043. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Kitis G, Sadek AM, Karsu Asal EC, Li Z. Thermoluminescence glow-curve deconvolution using analytical expressions: A unified presentation. Appl Radiat Isot. 2021 Feb;168:109440. [CrossRef]

- Stadtmann, H. , Wilding, G., 2017. Glow curve deconvolution for the routine readout of LiF: Mg,Ti. Radiat. Meas. 106, 278–284.

- Osorio, P.V. , Stadtmann, H., Lankmayr, E., 2001. A new algorithm for identifying abnormal glow curves in thermoluminescence personal dosimetry. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 96, 139–141.

- Osorio, P.V. , Stadtmann, H., Lankmayr, E., 2002. An example of abnormal glow curves identification in personnel thermoluminescent dosimetry. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 53, 117–122.

- Pradhan, S.M. , Sneha, C., Adtani, M.M., 2011. A method of identification of abnormal glow curves in individual monitoring using CaSO4:Dy teflon TLD and hot gas reader. Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 144, 195–198.

- Moscovitch M et al 1995 A TLD dose algorithm using artificial neural networks Radioact. Radiochem. 6 46a.

- Mentzel F, Derugin E, Jansen H, Kröninger K, Nackenhorst O, Walbersloh J and Weingarten J 2021 No more glowing in the dark: how deep learning improves exposure date estimation in thermoluminescence dosimetry J. Radiol. Prot. 41 S506.

- Toktamis D, Er M B and Isik E 2022 Classification of thermoluminescence features of the natural halite with machine learning Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 177 360–71.

- Kröninger K, Mentzel F, Theinert R and Walbersloh J 2019 A machine learning approach to glow curve analysis Radiat. Meas. 125 34–39.

- Mentzel F et al 2020 Extending information relevant for personal dose monitoring obtained from glow curves of thermoluminescence dosimeters using artificial neural networks Radiat. Meas. 136 106375.

- Isik E 2022 Thermoluminescence characteristics of calcite with a Gaussian process regression model of machine learning Luminescence 37 1321–7.

- Pathan M S, Pradhan S M, Selvam T P and Sapra B K 2023 A machine learning approach for correcting glow curve anomalies in CaSO4 : Dy-based TLD dosimeters used in personnel monitoring J. Radiol. Prot. 43 031503.

- Pathan M S, Pradhan S M and Palani Selvam T 2020 Machine learning algorithms for identification of abnormal glow curves and associated abnormality in CaSO4 :Dy-based personnel monitoring dosimeters Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 190 342–51.

- G. Amit, H. Datz. Improvement of Dose Estimation Process Using Artificial Neural Networks. Radiation Protection Dosimetry, pp 1-8 (2018). [CrossRef]

- G. Amit, G. Datz. Automatic detection of anomalous thermoluminescent dosimeter glow curves using machine learning. Radiation Measurements 2018, 117, 80–85. [CrossRef]

- G. Amit, H. Datz. Computerized Categorization of TLD Glow Curve Anomalies Using Multi-Class Classification Support Vector Machines. Radiation Measurements 125, pp 1-6 (2019).

- Pathan M S, Pradhan S M, Datta D and Selvam T P 2019 Study of effect of consecutive heating on thermoluminescence glow curves of multi-element TL dosemeter in hot gas-based reader system Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 187 509–17.

- Sadek A M, Abdou N Y and Alazab H A 2022 Uncertainty of LiF thermoluminescence at low dose levels: experimental results Appl. Radiat. Isot. 185 110245.

- Uncertainty of thermoluminescence at low dose levels: a Monte-Carlo simulation study. Radiat. Protect. Dosim., 192 (2020), pp. 14-26.

- Piniella V O, Stadtmann H and Lankmayr E 2002 An example of abnormal glow curves identification in personnel thermoluminescent dosimetry J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 53 117–22.

- Pradhan S M, Sneha C and Adtani M M 2011 A method of identification of abnormal glow curves in individual monitoring using CaSO4:Dy Teflon TLD and hot gas reader Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 144 195–8.

- Pathan M S, Pradhan S M and Selvam T P 2020 Machine learning algorithms for identification of abnormal glow curves and associated abnormality in CaSO4:Dy-based personnel monitoring dosimeters Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 190 342–51.

- Horowitz, Y.S. , Oster, L., Datz, H., 2007. The thermoluminescence dose–response and other characteristics of the high-temperature TL in LiF:Mg,Ti (TLD-100). Radiat. Protect. Dosim. 124, 191–205.

- Publication no. ALGM-W05-U-0908-003. WinAlgorithms: Dose Calculation Algorithm for Types 8805, 8810, 8814 and 8815 Dosimeters User’s Manual. Table 10.1 Characteristic Element Ratios.

- QlikTech International, AB. (2011), “Business Discovery: Powerful, User-Driven BI: A QlikView White Paper.” Retrieved from http://www.qlik.com/us/explore/resources/whitepapers/business-discovery-powerful-user-driven-bi.

| Definition | Sub class | Anomaly class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background TL signal at low temperatures | Low | Class A | |

| High background TL signal at high temperatures | High | ||

| Invalid GC width – too wide GC | Wide | Class B | |

| Invalid GC width – too narrow GC | Narrow | ||

| GC shifted towards low temperatures | Low | Class C | |

| GC shifted towards high temperatures | High | ||

| Too many spikes | - | Class D |

| Units | Description | Class / Module | Parameter name |

|---|---|---|---|

| mrem | Above this value, a dosimeter will be manually checked | General | ManualReviewThreshold |

| bool | Correct automatically without approval or not. | bFullAutomated | |

| mrem | Threshold under which 1st crystal is filtered out | Threshold1 | |

| Threshold under which 2nd crystal is filtered out | Threshold2 | ||

| Threshold under which 3rd crystal is filtered out | Threshold3 | ||

| Threshold under which neutron crystal is filtered out | ThresholdNeut | ||

| Threshold under which ring crystal is not checked | ThresholdRing | ||

| Weekly background | RadiationPerWeek | ||

| 0-1 | Ratio filter factor #1 | Crystals_Quotient | |

| 0-1 | Ratio filter factor #2 | ratio_table_threshold | |

| string | File path for winrems SQL data | MDBPath | |

| bool | Use AI filter | Machine Learning | bUseAI |

| - | ANN Model file name | training_model_file | |

| - | Above this threshold GC is classified normal | ai_probability_threshold | |

| % | Bgd max height relative to GC max height | Class A | MaxBgdHeight |

| Bgd min height relative to GC max height | MinBgdHeight | ||

| - | Minimal channel of high temperature | BgdHTTLChLow | |

| - | Maximal channel of high temperature | BgdHTTLChHigh | |

| - | Minimal channel of low temperature | BgdLTTLChLow | |

| - | Maximal channel of low temperature | BgdLTTLChHigh | |

| - | Max channel index for A_LTTL cut | LowCutCh | |

| - | Min channel index for A_HTTL cut | HighCutCh | |

| - | Minimal channel for width measure | Class B | TLDWideLowCh |

| - | Maximal channel for width measure | TLDWideHighCh | |

| % | Average height between minimal and maximal channels relative to max GC height | WideAvgVal | |

| - | Half width of narrow GC in # of channels unit | half_width_num_ch | |

| % | GC height relative to max height outside the narrow channels | NarrowAvgVal | |

| - | Max allowed shift from channel 95 | MaxAllowedShift | |

| - | Number of spikes found in GC | Class D | NSpikes |

| % | Percent difference between two neighbor channels | SpikeNeighDiff |

| L4/L3 | L3/L1 | L3/L2 | L1/L4 | E(keV) | Beam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 7.80 | 2.10 | 0.15 | 20 | NS 25 |

| 0.92 | 3.19 | 1.47 | 0.34 | 24 | NS30 |

| 0.95 | 1.50 | 1.15 | 0.70 | 33 | NS40 |

| 0.96 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 48 | NS60 |

| 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.09 | 65 | NS80 |

| 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.11 | 83 | NS100 |

| 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 100 | NS120 |

| 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 118 | NS150 |

| 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 164 | NS200 |

| 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 208 | NS250 |

| 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 250 | NS300 |

| 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 118 | H150 |

| 0.79 | 8.88 | 2.90 | 0.14 | 20 | M30 |

| 0.93 | 1.96 | 1.35 | 0.55 | 35 | M60 |

| 0.96 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 53 | M100 |

| 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 73 | M150 |

| 0.96 | 1.41 | 1.15 | 0.74 | 38 | S60 |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 662 | Cs137 |

| 0.00 | 6200 | 6200 | 0.05 | Tl204 | |

| 0.30 | 4.98 | 67.5 | 0.68 | Sr90 / Y90 | |

| 0.23 | 6.44 | 24.2 | 0.69 | DU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).