1. Introduction

Individuals aged 80 years and older constitute a distinct age group referred to as the "oldest old" [

1]. With the global increase in life expectancy, this population is projected to triple by the year 2050 [

2]. The growing elderly population places a significant burden on healthcare systems by increasing the demand for medical care. Especially in oldest old individuals, the high burden of comorbid diseases, weakened immune systems and decreased functional capacity increase the susceptibility to infections and increase the risk of complications. Pneumonia in oldest old patients is often associated with more severe clinical presentations and frequently necessitates intensive care admission in the presence of any infection [

3]. Moreover, the incidence of pneumonia cases requiring intensive care among this age group has been reported to be rising [

4]. Therefore, accurate prediction of disease prognosis in oldest old individuals is of great importance to ensure early and appropriate interventions.

Neutrophils are key components of the innate immune system and serve as the first line of defense against infections. During infectious and inflammatory processes, changes in neutrophil levels act as important biomarkers that reflect disease severity and systemic inflammation [

5]. Albumin, on the other hand, is a major plasma protein with antioxidant properties and plays a critical role in modulating immune responses. Albumin levels may decrease due to inflammation, nutritional status, and alterations in organ function, and this decline is closely associated with disease severity [

6].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the prognostic value of inflammatory biomarkers, with the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) emerging as a novel parameter in this context [

7]. NPAR is being investigated as an indicator of inflammation and systemic response in both acute and chronic disease settings [

8]. Current studies suggest that NPAR may be associated with the prognosis of various clinical conditions such as acute kidney injury, stroke, cardiovascular diseases, and sepsis [

9,

10,

11]. However, data on the relationship between NPAR and disease progression in elderly patients with pneumonia, as well as its potential clinical utility, remain limited. In this study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of NPAR in elderly patients with pneumonia and to evaluate its impact on disease severity and clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study included patients aged 80 years and older who were followed in the intensive care units of our hospital between October 1, 2022, and May 31, 2024. Data of patients diagnosed with pneumonia were retrospectively reviewed using the hospital information system and medical records.

This study was approved by the Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee with the decision number 2839 dated July 16, 2024 and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The diagnosis of pneumonia was established based on the presence of the following three criteria after excluding alternative diagnoses:

Symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection: Fever (>38°C), cough, purulent sputum, or a change in the character of respiratory secretions.

Radiographic findings consistent with pneumonia: Newly developed infiltrates on chest radiography or thoracic computed tomography.

Laboratory findings suggestive of infection: Leukocytosis, leukopenia, or elevated acute phase reactants.

2.1. Exclusion Criteria: Patients Who Were Not Included in the Study Were Identified Based on the Following Exclusion Criteria

Incomplete or insufficient patient data: Missing essential clinical, laboratory, or radiological data in the hospital information system or patient records.

Primary diagnoses other than pneumonia: Patients whose primary diagnosis was not pneumonia and who had alternative conditions that could mimic lower respiratory tract infections (e.g., pulmonary embolism, pulmonary edema due to congestive heart failure, interstitial lung diseases, pulmonary infiltrates due to malignancy).

Immunosuppressed patients: Patients with a history of chemotherapy, long-term corticosteroid use (>20 mg/day prednisone equivalent), immunosuppressive therapy, or solid organ/bone marrow transplantation.

Severe hematologic diseases: Patients with significant immune system impairment due to leukemia, lymphoma, or severe bone marrow failure.

End-stage renal or liver failure: Patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease (stage 5 requiring dialysis) or cirrhosis classified as Child-Pugh class C.

Diseases associated with hypoalbuminemia: Patients diagnosed with conditions that could cause hypoalbuminemia, such as chronic liver diseases or nephrotic syndrome.

2.2. Data Collection and Evaluation

Patients’ comorbidities were recorded, and the most common comorbidities were identified. The impact of these comorbidities on mortality was also analyzed. Demographic data, clinical findings, complete blood count and biochemical parameters obtained within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, acute phase reactants, imaging findings, administered treatments, need for respiratory and vasopressor support, requirement for renal replacement therapy, and patient outcomes were collected through the hospital information system and patient files.

In this study, the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) was calculated and its association with clinical outcomes was analyzed. Neutrophil percentage was measured using the Mindray BC-6800 automated hematology analyzer (Shenzhen Mindray Bio-medical Electronics Co., Ltd., China) and recorded as a percentage. Serum albumin levels were measured in g/L using the Beckman Coulter AU680 chemistry analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). NPAR was calculated by dividing the neutrophil percentage by the serum albumin level.

2.3. Assessment of Sepsis and Disease Severity

Sepsis was defined according to the Sepsis-3 International Consensus Criteria. In patients diagnosed with pneumonia, sepsis was identified when the Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was ≥2. Patients who required vasopressor support to maintain a mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg despite adequate fluid resuscitation were considered to have septic shock.

To objectively assess disease severity, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, which is widely used in intensive care settings, was calculated.

2.4. Calculation of SpO₂/FiO₂

In this study, the SpO₂/FiO₂ ratio was calculated to evaluate the patients' oxygenation status. SpO₂ values were obtained using a standard pulse oximeter, and the FiO₂ level was recorded based on the concentration of inspired oxygen. For patients receiving supplemental oxygen, FiO₂ was estimated according to the oxygen flow rate and the method of oxygen delivery. The SpO₂/FiO₂ ratio was calculated by dividing the SpO₂ value by the FiO₂ value. This ratio was used to classify the hypoxemic status of patients.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). The normality of distribution for continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD), while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR, 25th–75th percentiles). Appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests were used to compare differences between groups. For comparisons between two independent groups, the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was applied for continuous variables. The chi-square test (χ²) or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. The prognostic performance of NPAR in predicting mortality was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each variable, and optimal cutoff values were presented along with sensitivity and specificity. For survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated, and differences between groups were assessed using the Log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with mortality. Initially, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to identify candidate variables, and significant variables were then included in the multivariate model. Results of the model were reported as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 135 patients were included in the study. Patients were divided into two groups as NPAR ≤ 0.286 and NPAR> 0.286, based on the cut-off value of 0.286 determined as a result of ROC analysis to evaluate the prognostic value of NPAR.

When the clinical characteristics of the patients were compared between groups, disease severity markers were found to be higher and mortality rates significantly increased in the high NPAR group. SOFA (p = 0.002) and APACHE II (p = 0.007) scores were significantly higher in patients with elevated NPAR. The need for invasive mechanical ventilation (p = 0.003), vasopressor therapy (p = 0.042), and the incidence of sepsis (p = 0.035) were also significantly greater in the high NPAR group. Moreover, mortality was significantly higher in patients with elevated NPAR (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients According to Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio (NPAR) Levels.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients According to Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio (NPAR) Levels.

| Variable |

All Patients 135 (100%)

N (%)

Mean ± SD |

NPAR ≤ 0.286 48 (35.6%)

N (%)

Mean ± SD *

|

NPAR > 0.286 87 (64.4%)

N (%)

Mean ± SD |

p-value |

| Age (years) |

86.87 ± 4.95 |

86.65 ± 5.23 |

86.99 ± 4.82 |

0.638 |

| Male sex |

66 (48.9%) |

22 (33.3%) |

44 (66.7%) |

0.599 |

| SOFA score |

6.84 ± 3.00 |

5.85 ± 2.94 |

7.39 ± 2.90 |

0.002 |

| APACHE II score |

22.83 ± 6.63 |

20.90 ± 7.53 |

23.90 ± 5.85 |

0.007 |

| Renal replacement therapy |

33 (24.4%) |

10 (20.8%) |

23 (26.4%) |

0.470 |

| Vasopressor requirement |

43 (31.9%) |

10 (20.8%) |

33 (37.9%) |

0.042 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation |

60 (44.4%) |

13 (27.1%) |

47 (54.0%) |

0.003 |

| Presence of comorbidities |

111 (82.2%) |

47 (97.9%) |

64 (73.6%) |

<0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease |

50 (37.0%) |

25 (52.1%) |

25 (28.7%) |

0.007 |

| Hypertension |

67 (49.6%) |

34 (70.8%) |

33 (37.9%) |

<0.001 |

| Severity of the disease |

|

|

|

|

| No sepsis |

41 (30.4%) |

20 (41.7%) |

21 (24.1%) |

0.035 |

| Sepsis |

94 (69.6%) |

28 (58.3%) |

66 (75.9%) |

| SpO2/FiO2** |

|

|

|

|

| SpO₂/FiO₂ > 315 |

21 (15.6%) |

6 (12.5%) |

15 (17.2%) |

0.087 |

| 235 < SpO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 315 |

43 (31.9%) |

21 (43.8%) |

22 (25.3%) |

| 148 < SpO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 235 |

42 (31.8%) |

17 (35.4%) |

25 (28.7%) |

| SpO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 148 |

29 (21.5%) |

4 (8.3%) |

25 (28.7%) |

| Mortality |

53 (39.3%) |

9 (18.8%) |

44 (50.6%) |

<0.001 |

When laboratory findings were compared according to NPAR levels, inflammatory and metabolic markers were found to be significantly elevated in the high NPAR group. Higher NPAR levels were associated with increased procalcitonin (p = 0.020) and lactate (p = 0.003) levels (

Table 2).

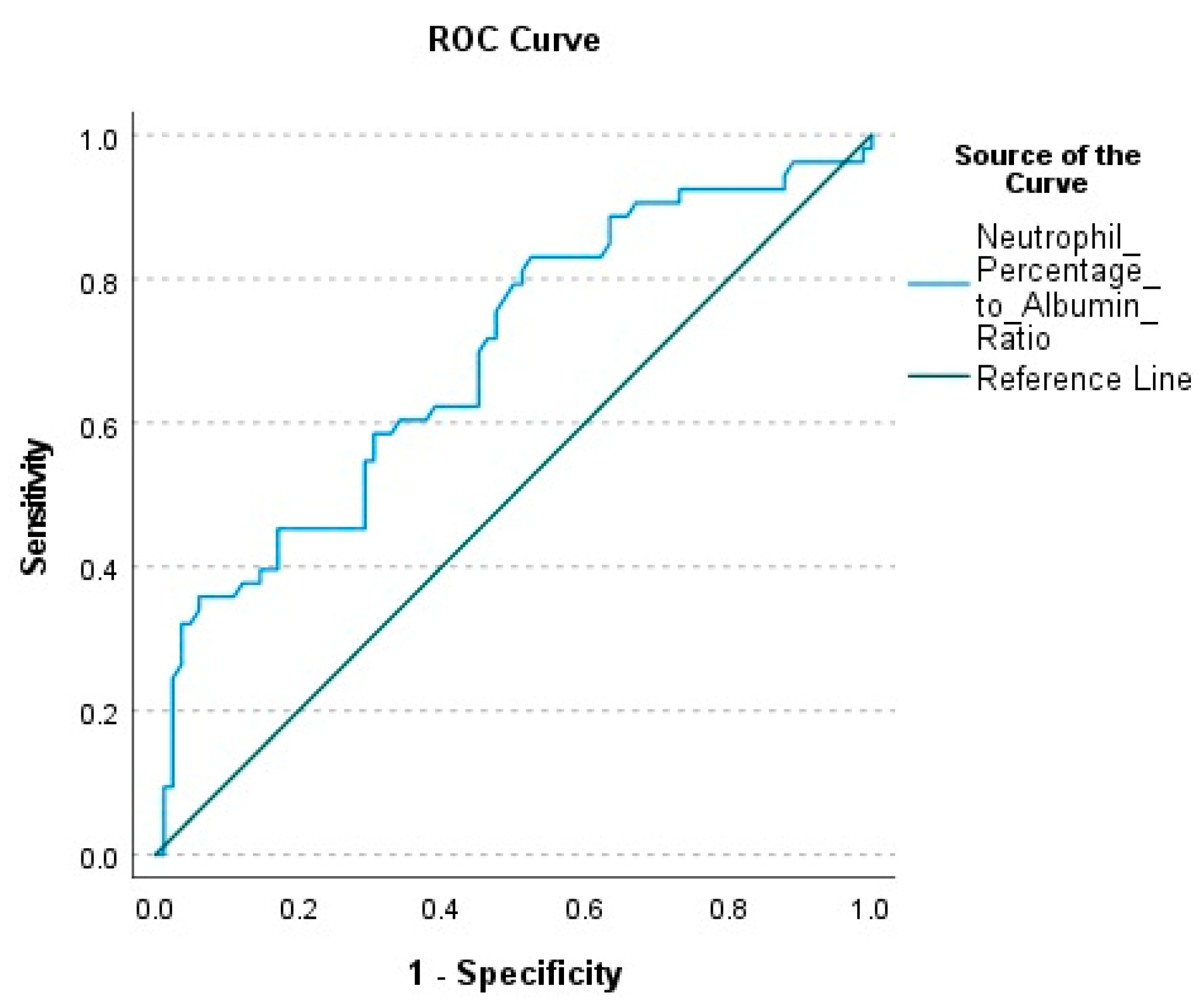

NPAR was calculated as 0.291 (0.244–2.16) in survivors and 0.422 (0.298–3.092) in deceased patients. This difference between the groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The AUC value calculated to evaluate the mortality prediction power of NPAR was found to be 0.692. (p < 0.001). The optimal cut-off value was determined as 0.286, with a sensitivity of 83%, specificity of 47.6%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 50.6%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 81.2% (

Table 3) (

Figure 1).

In the univariate Cox regression analysis, patients with NPAR > 0.286 had a significantly increased risk of mortality (HR = 3.318, 95% CI: 1.616–6.812, p = 0.001). Similarly, mortality was significantly increased in patients with high APACHE-II and SOFA scores. The need for renal replacement therapy and vasopressor support were also significantly related to mortality. The strongest association was observed with the requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV); patients who required IMV had an approximately 20-fold higher risk of mortality (HR = 20.297, 95% CI: 8.019–51.374, p < 0.001). In contrast, variables such as cardiovascular disease (p = 0.524), hypertension (p = 0.172), and the presence of comorbidities (p = 0.078) were not significantly associated with mortality.

In the multivariate analysis, an NPAR level > 0.286 was identified as an independent risk factor for mortality (HR = 2.488, 95% CI: 1.167–5.302, p = 0.018). The APACHE II score remained significantly associated with increased mortality risk (HR = 1.077, 95% CI: 1.013–1.147, p = 0.019), whereas the SOFA score was not found to be an independent predictor in the multivariate model (p = 0.156). The need for renal replacement therapy was also determined to be an independent predictor of mortality (HR = 1.969, 95% CI: 1.046–3.705, p = 0.036). The requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation remained the strongest independent risk factor.

Table 4.

Cox Regression Analysis Results for Factors Associated with Mortality.

Table 4.

Cox Regression Analysis Results for Factors Associated with Mortality.

| Variable |

Univariate Cox Regression |

Multivariate Cox Regression |

| |

HR (95% CI) |

p-value |

HR (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Presence of comorbidities |

2.290 (0.911–5.760) |

0.078 |

|

|

| Cardiovascular disease |

0.830 (0.469–1.471) |

0.524 |

|

|

| Hypertension |

0.682 (0.394–1.180) |

0.172 |

|

|

| APACHE II score |

1.163 (1.118–1.209) |

<0.001 |

1.077 (1.013–1.147) |

0.019 |

| SOFA score |

1.291 (1.193–1.398) |

<0.001 |

1.100 (0.964–1.254) |

0.156 |

| NPAR* > 0.286 |

3.318 (1.616–6.812) |

0.001 |

2.488 (1.167–5.302) |

0.018 |

| Need for renal replacement therapy |

3.788 (2.185–6.567) |

<0.001 |

1.969 (1.046–3.705) |

0.036 |

| Need for vasopressor therapy |

4.166 (2.385–7.279) |

<0.001 |

0.616 (0.311–1.220) |

0.165 |

| Need for invasive mechanical ventilation |

20.297 (8.019–51.374) |

<0.001 |

9.446 (3.402–26.229) |

<0.001 |

When comorbid conditions were evaluated, the rates of hypertension and cardiovascular disease were found to be higher in the low NPAR group (p < 0.001 and p = 0.007, respectively). However, when the association of comorbidities with mortality was assessed using Cox regression analysis, neither hypertension (p = 0.172) nor cardiovascular disease (p = 0.524) showed a statistically significant relationship.

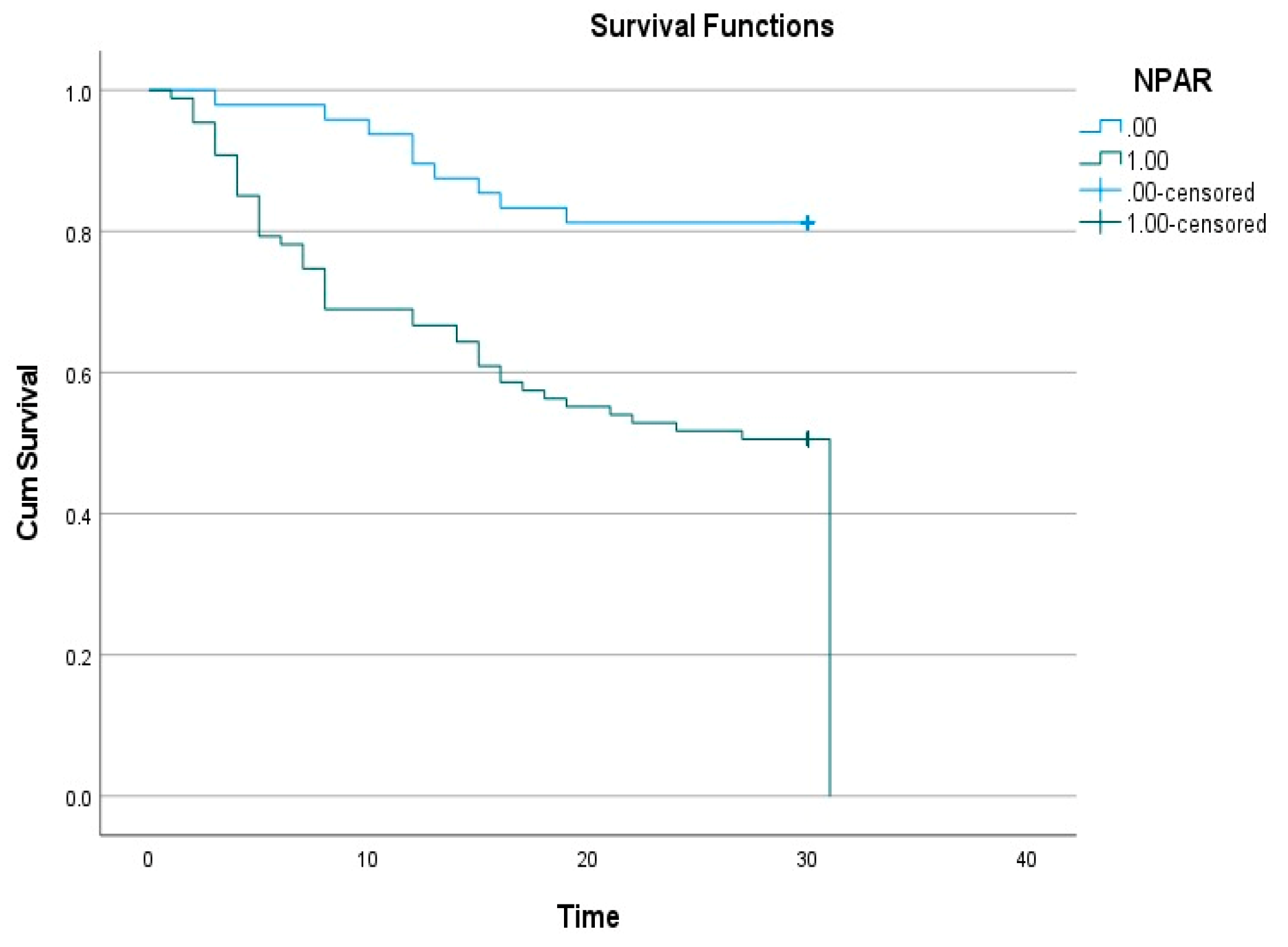

According to the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, the survival rate was significantly lower in the high NPAR group (

Figure 2). The log-rank test revealed a statistically significant difference in survival times between the NPAR groups (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to evaluate the prognostic value of the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) in pneumonia patients aged 80 years and older admitted to the intensive care unit. Our findings demonstrate that elevated NPAR levels are significantly associated with disease severity markers such as SOFA and APACHE II scores, and may be linked to worse clinical outcomes during the intensive care course. The results of the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that higher NPAR levels were associated with significantly lower survival rates. Furthermore, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, NPAR was identified as an independent predictor of mortality, and this association was found to be independent of other clinical variables such as comorbidities, disease severity, and organ failure. Elevated NPAR was also significantly associated with the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), vasopressor use, and the development of sepsis. This suggests that NPAR may also reflect critical clinical conditions such as hemodynamic instability and organ dysfunction. Based on these findings, NPAR—being a simple, rapid, and widely accessible laboratory parameter—may be considered a clinically useful biomarker for predicting disease severity and mortality risk in pneumonia patients aged 80 years and older. However, for a more comprehensive evaluation of this relationship, large-scale, multicenter prospective studies including different patient populations are needed.

Serum albumin is a negative acute-phase reactant associated with inflammatory processes and exerts antioxidant effects through its interaction with bioactive lipid mediators that play key roles in the immune system [

12]. Malnutrition has previously been shown to be associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with pneumonia [

13]. It is well established that, with advancing age, nutritional deficiencies are directly related to immune system impairment. In our study, hypoalbuminemia, along with elevated NPAR, was significantly associated with increased mortality. This finding suggests that low albumin levels may influence pneumonia prognosis through mechanisms related to both inflammation and nutritional status. Therefore, in elderly patients with pneumonia, clinicians should consider not only nutritional status but also the underlying inflammatory state. When necessary, in addition to early nutritional support, interventions targeting the control of the inflammatory response should also be prioritized.

Neutrophils are key components of the systemic inflammatory response to infection and represent one of the most important cells of the innate immune system. Moreover, they are known to be closely associated with organ dysfunction in the setting of severe infections and sepsis [

14]. In recent years, NPAR has been evaluated across various disease groups and has emerged as a promising prognostic biomarker. Elevated NPAR levels have been shown to be associated with mortality in patients with cerebrovascular diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [

8,

9,

15]. In a study conducted on ICU patients diagnosed with sepsis, NPAR measured at admission was reported to be a significant predictor of 28-day mortality [

16]. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated that increased NPAR is associated with mortality in pneumonia patients aged 80 years and older.

According to the intensive care unit admission criteria established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the need for vasopressors and mechanical ventilation are considered major indicators in critically ill patients [

17]. In our study, mortality was found to be higher in patients who required vasopressor support and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), and these factors were identified as independent predictors of mortality. Additionally, patients with elevated NPAR levels were significantly more likely to require vasopressor therapy and IMV. These findings suggest that NPAR may reflect not only inflammatory processes but also critical clinical conditions such as hemodynamic instability and respiratory failure.

The APACHE II and SOFA scores are widely used scoring systems for assessing disease severity and predicting mortality in critically ill patients [

18,

19,

20]. In our study, the APACHE II score was found to be an independent prognostic predictor of mortality, whereas the SOFA score did not remain significant in the multivariate analysis. Additionally, increases in both APACHE II and SOFA scores were significantly associated with elevated NPAR levels. An NPAR level > 0.286 was shown to be an independent predictor of mortality. These findings suggest that NPAR may serve as a biomarker reflecting disease severity and could assist in the early identification of clinical deterioration. However, large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are needed to validate these findings.

This study has several limitations. First, due to its single-center and retrospective design, the generalizability of the findings to broader populations is limited. Additionally, data on the timing of antibiotic initiation and the duration between hospital admission and ICU transfer were not available, which prevented a comprehensive assessment of their impact on mortality and disease severity. When evaluating the prognostic power of NPAR, it was observed that while its sensitivity was high, its specificity was relatively low. This suggests that NPAR alone may not be sufficient for mortality prediction and should be interpreted in conjunction with other prognostic markers. Lastly, the lack of long-term follow-up data to assess temporal changes and the dynamic course of NPAR represents a significant limitation in determining its prognostic utility. Therefore, large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are warranted to more thoroughly evaluate the clinical utility and prognostic potential of NPAR.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) may serve as a prognostic biomarker in pneumonia patients aged 80 years and older admitted to the intensive care unit. Elevated NPAR levels were significantly associated with increased disease severity, higher mortality, and a greater need for invasive mechanical ventilation. Cox regression analysis identified NPAR as an independent predictor of mortality, supporting its potential for clinical use. Given that it is an easily calculable and widely accessible parameter, NPAR may be a useful adjunct biomarker in predicting mortality and guiding clinical decision-making in elderly patients with pneumonia. However, large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are needed to validate these findings and further assess the role of NPAR in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and A.H.S.; methodology, T.Ö. and M.Y.; software, O.M. and D.Ç.; validation, M.D. and G.E.D.; formal analysis, E.A., H.T.M. and Ö.F.T.; investigation, M.A. and E.U.; resources, M.A. and A.H.S.; data curation, O.M., H.T.M. and Ö.F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and A.H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and G.E.D.; visualization, E.U.; supervision, D.Ç.; project administration, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding: grants, or other support was received for conducting this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Ankara Ataturk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital (Decision no: 2839, dated 16.07.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cillóniz C.; Dominedò C.; Pericàs J. M.; Rodriguez-Hurtado D.; Torres A. Community- acquired pneumonia in critically ill very old patients: a growing problem. Eur Respir Rev. 2020, Vol. 19;29(155):190126. [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: World Population Prospects 2019. Ten Key Findings,. 2019.

- Lee S. I.; Huh J. W.; Hong S. B.; Koh Y.; Lim C. M. Age Distribution and Clinical Results of Critically Ill Patients above 65-Year-Old in an Aging Society: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2024, Vols. 87(3):338-348.

- Laporte L.; Hermetet C.; Jouan Y.; Gaborit C.; Rouve E.; Shea K. M.; Si-Tahar M.; Dequin P. F.; Grammatico-Guillon L.; Guillon A. Ten-year trends in intensive care admissions for respiratory infections in the elderly. Ann Intensive Care. 2018, Vol. 15;8(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Othman A.; Sekheri M.; Filep J. G. Roles of neutrophil granule proteins in orchestrating inflammation and immunity. FEBS J. 2022 , Vols. 289(14):3932-3953.

- Eckart A.; Struja T.; Kutz A.; Baumgartner A.; Baumgartner T.; Zurfluh S.; Neeser O.; Huber A.; Stanga Z.; Mueller B.; et al. Relationship of Nutritional Status, Inflammation, and Serum Albumin Levels During Acute Illness: A Prospective Study. Am J Med. 2020, Vols. 133(6):713-722.e7. [CrossRef]

- Liu C. F.; Chien L. W. Predictive Role of Neutrophil-Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio (NPAR) in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Nondiabetic US Adults: Evidence from NHANES 2017-2018. Nutrients. 2023, Vol. 14;15(8):1892.

- Lan C. C.; Su W. L.; Yang M. C.; Chen S. Y.; Wu Y. K. Predictive role of neutrophil- percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: Evidence from NHANES 2011-2018. Respirology. 2023, Vol. 28(12):11.

- Lv X. N.; Shen Y. Q.; Li Z. Q.; Deng L.; Wang Z. J.; Cheng J.; Hu X.; Pu M. J.; Yang W. S.; Xie P.; et al. Neutrophil percentage to albumin ratio is associated with stroke- associated pneumonia and poor outcome in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 2023, Vol. 14;14:1173718.

- Cai J.; Li M.; Wang W.; Luo R.; Zhang Z.; Liu H. The Relationship Between the Neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin Ratio and Rates of 28-Day Mortality in Atrial Fibrillation Patients 80 Years of Age or Older. J Inflamm Res. 2023, Vols. 17;16:1629-163.

- Xu M.; Huan J.; Zhu L.; Xu J.; Song K. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2024, Vol. 46(1):2294149.

- Wiedermann C. J. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, Vol. 26;22(9):4496. [CrossRef]

- Lin C. J.; Chang Y. C.; Tsou M. T.; Chan H. L.; Chen Y. J.; Hwang L. C. Factors associated with hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in home health care patients in Taiwan. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020, Vols. 32(1):149-155.

- Zhang F.; Zhang Z.; Ma X. Neutrophil extracellular traps and coagulation dysfunction in sepsis. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2017, Vols. 29(8):752-755.

- Wang X.; Zhang Y.; Wang Y.; Liu J.; Xu X.; Liu J.; Chen M.; Shi L. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023, Vol. 18;23(1):568.

- Hu C.; He Y.; Li J.; Zhang C.; Hu Q.; Li W.; Hao C. Association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio and 28-day mortality in Chinese patients with sepsis. J Int Med Res. 2023, Vol. 51(6):3000605231178512.

- Mandell L. A.; Wunderink R. G.; Anzueto A.; Bartlett J. G.; Campbell G. D.; Dean N. C.; Dowell S. F.; File T. M. Jr.; Musher D. M.; Niederman M. S.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, Vol. 1;44.

- Farajzadeh M.; Nasrollahi E.; Bahramvand Y.; Mohammadkarimi V.; Dalfardi B.; Anushiravani A. The use of APACHE II Scoring System for predicting clinical outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a report from a resource-limited center. Shraz E-Med J. 2021, Vol. 22:e102858.

- Mumtaz H.; Ejaz M. K.; Tayyab M.; Vohra L. I.; Sapkota S.; Hasan M.; Saqib M. APACHE scoring as an indicator of mortality rate in ICU patients: a cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023, Vols. 24;85(3):416-421. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh N.; Hasheminik M.; Shafigh E.; Alipour H.; Sayyadi S.; Kazeminia N.; Khoundabi B.; Salarian S. Prediction of mortality in ICU patients: A comparison between the SOFA score and other indicators. Nurs Crit Care. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).