Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

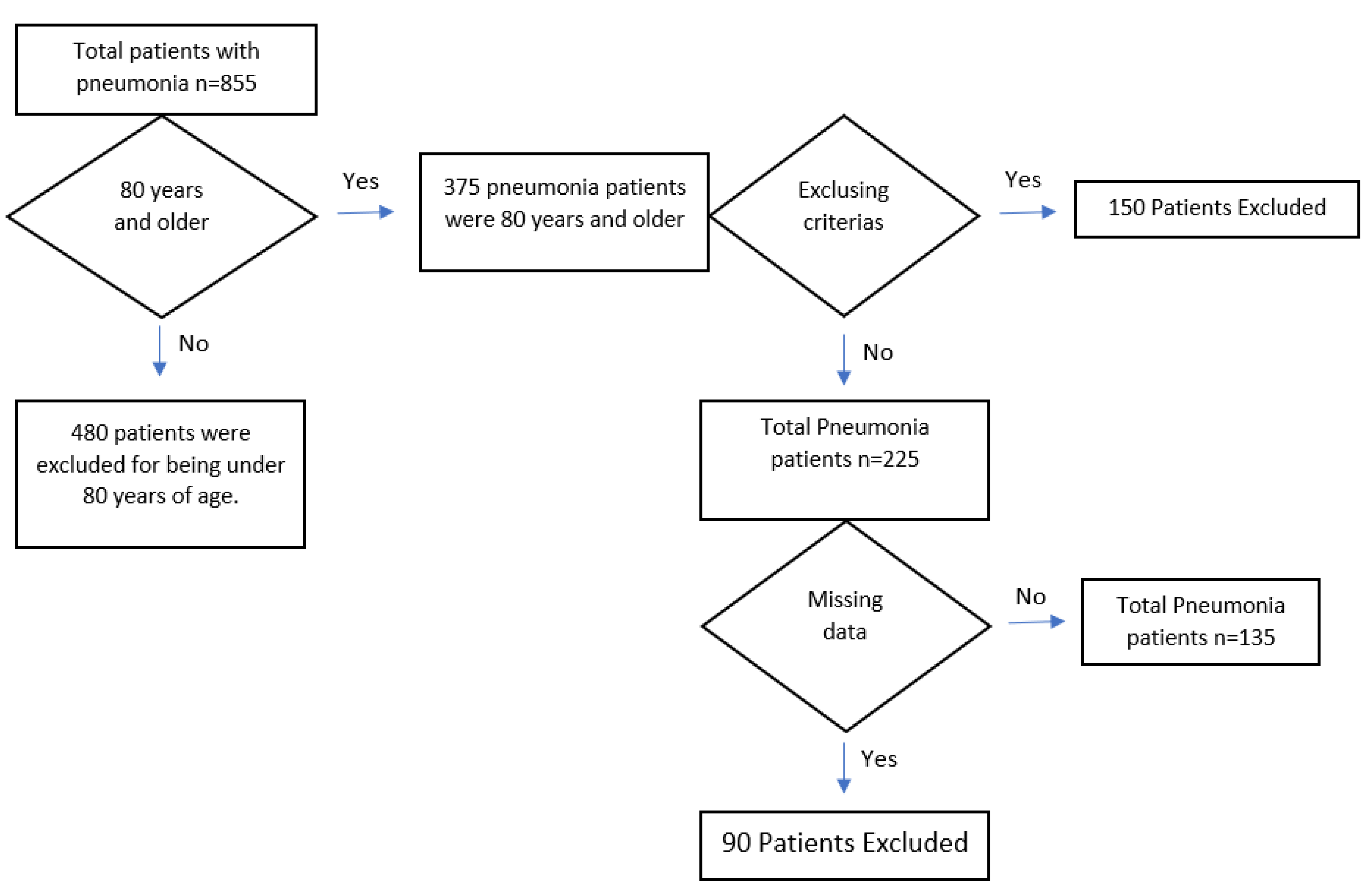

Objectives: Individuals aged 80 and above, classified as the oldest old, are a growing population frequently requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admissions due to pneumonia. The disease in this group is complicated by comorbidities, immune dysfunction, and antibiotic-resistant infections. This study aimed to identify factors influencing mortality in elderly ICU patients. Materials and Methods: This retrospective study included 135 patients aged 80+ diagnosed with pneumonia in the ICU. Demographic data, clinical findings, laboratory results, and outcomes were analyzed. APACHE-II and SOFA scores were calculated upon admission. One-month in-hospital mortality was the primary endpoint, and predictors of mortality were examined. Results: The average age was 86.87, with a 39.2% mortality rate. APACHE II and SOFA scores were strong predictors of mortality. Factors associated with increased mortality included hemodialysis(p<0.001), invasive mechanical ventilation(p<0.001), low albumin(p=0.006), high procalcitonin(p=0.003), Neutrophil Percentage/Albumin Ratio (NPAR)(p<0.001), urea (p<0.001), and creatinine(p=0.010). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) emerged as an independent risk factor. Conclusions: Mortality in elderly pneumonia patients is multifactorial. APACHE II, SOFA scores, and markers such as NPAR and COPD significantly affect outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of strategies to prevent organ dysfunction, monitor nutritional status, and manage infections in this vulnerable population.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selecetion

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria for Pneumonia

- Presence of lower respiratory tract infection symptoms: fever (>38°C), cough, purulent sputum, or changes in the characteristics of respiratory secretions.

- Radiographic infiltration consistent with pneumonia.

- Laboratory findings compatible with an infection diagnosis: leukocytosis, leukopenia, or increases in acute-phase reactants.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Microbiological Analysis

2.5. Sepsis and Severity Scoring

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019: Ten Key Findings. 2019.

- Cillóniz C, Dominedò C, Pericàs JM et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in critically ill very old patients: a growing problem. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(155):190126.

- Lee SI, Huh JW, Hong SB, Koh Y, Lim CM. Age distribution and clinical results of critically ill patients above 65 years old in an aging society: A retrospective cohort study. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2024;87(3):338-348.

- Niederman MS. Natural enemy or friend? Pneumonia in the very elderly critically ill patient. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(155):200031.

- Laporte L, Hermetet C, Jouan Y et al. Ten-year trends in intensive care admissions for respiratory infections in the elderly. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):84.

- Ozturk R, Kinikli S, Cesur S. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Turkish Journal of Clinics and Laboratory. 2015;63-72.

- Ulug M, Celen MK, Geyik MG et al. The evaluation of cultures of endotracheal aspirates and isolated bacteria in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Düzce Medical Journal. 2011;13(1):21-25.

- Montull B, Menéndez R, Torres A et al. Predictors of severe sepsis among patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145929.

- Williams JC, Ford ML, Coopersmith CM. Cancer and sepsis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023;137(11):881-893.

- Ma H, Liu T, Zhang Y et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res. 2020;9(12):839-848.

- Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44.

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW. Update in adult community-acquired pneumonia: key points from the new American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America 2019 guideline. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(3):203-207.

- Farajzadeh M, Nasrollahi E, Bahramvand Y et al. The use of APACHE II scoring system for predicting clinical outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a report from a resource-limited center. Shiraz E-Med J. 2021;22:e102858.

- Mumtaz H, Ejaz MK, Tayyab M et al. APACHE scoring as an indicator of mortality rate in ICU patients: a cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(3):416-421.

- Shafigh N, Hasheminik M, Shafigh E et al. Prediction of mortality in ICU patients: A comparison between the SOFA score and other indicators. Nurs Crit Care. 2023.

- Do SN, Dao CX, Nguyen TA et al. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score for predicting mortality in patients with sepsis in Vietnamese intensive care units: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e064870.

- Peerapornratana S, Manrique-Caballero CL, Gómez H et al. Acute kidney injury from sepsis: current concepts, epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. Kidney Int. 2019;96(5):1083-1099.

- Chen X, Guo J, Mahmoud S et al. Regulatory roles of SP-A and exosomes in pneumonia-induced acute lung and kidney injuries. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1188023.

- Wiedermann CJ. Hypoalbuminemia as surrogate and culprit of infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4496.

- Lin CJ, Chang YC, Tsou MT et al. Factors associated with hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in home health care patients in Taiwan. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(1):149-155.

- Cui N, Zhang H, Chen Z et al. Prognostic significance of PCT and CRP evaluation for adult ICU patients with sepsis and septic shock: retrospective analysis of 59 cases. J Int Med Res. 2019;47(4):1573-1579.

- Kahveci U, Ozkan S, Melekoglu A et al. The role of plasma presepsin levels in determining the incidence of septic shock and mortality in patients with sepsis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(1):123-130.

- Maves RC, Enwezor CH. Uses of procalcitonin as a biomarker in critical care medicine. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(4):897-909.

- Self WH, Grijalva CG, Williams DJ et al. Procalcitonin as an early marker of the need for invasive respiratory or vasopressor support in adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2016;150(4):819-828.

- Tan M, Lu Y, Jiang H, Zhang L. The diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for sepsis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(4):5852-5859.

- Schupp T, Weidner K, Rusnak J et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin during the course of sepsis and septic shock. Ir J Med Sci. 2024;193(1):457-468.

- Zhang F, Zhang Z, Ma X. Neutrophil extracellular traps and coagulation dysfunction in sepsis. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2017;29(8):752-755.

- Lan CC, Su WL, Yang MC, Chen SY et al. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: Evidence from NHANES 2011-2018. Respirology. 2023;28(12):11.

- Lv XN, Shen YQ, Li ZQ et al. Neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with stroke-associated pneumonia and poor outcome in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1173718.

- Wang X, Zhang Y, Wang Y et al. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):568.

- Hu C, He Y, Li J et al. Association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio and 28-day mortality in Chinese patients with sepsis. J Int Med Res. 2023;51(6):3000605231178512.

| Variable | All Patients (N=135, %100) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Comorbidities | 111 (82.2%) |

| Hypertension | 67 (49.6%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 25 (18.5%) |

| Neurological Disease | 33 (24.4%) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 46 (34.1%) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 19 (14.1%) |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 50 (37%) |

| Malignancy | 10 (7.4%) |

| Bacterial Growth in Cultures | 78 (57.7%) |

| Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Growth | 30 (22.2%) |

| Survivors (N=82, %60.8) N (%) Mean±SD |

Deceased (N=53,%39.2) N (%) Mean±SD |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), | 86.37±4.90 | 87.64±4.97 | 0.463 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 38 (57.6%) | 28 (42.4%) | 0.163 |

| Male | 44 (63.8%) | 25 (36.2%) | |

| Presence of resistant bacteria in culture | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (56.7%) | 0.027 |

| SOFA Score | 5.59±2.57 | 8.79±2.56 | <0.001 |

| APACHE-II Score | 19.35±5.71 | 28.21±3.73 | <0.001 |

| Need for hemodialysis | 9 (10.9%) | 24 (89.1%) | <0.001 |

| Need for vasopressors | 11 (12.1%) | 32 (87.9%) | <0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 9.39±8.33 | 10.32±7.09 | 0.198 |

| Need for invasive mechanical ventilation | 12 (14.6%) | 48 (85.4%) | <0.001 |

| Duration on mechanical ventilation (days) | 1.34±4.29 | 4.43±4.55 | <0.001 |

| Presence of comorbidity | 63 (76.8%) | 48 (90.6%) | 0.042 |

| COPD* | 22 (26.8%) | 24 (45.3%) | 0.028 |

| Malignancy | 3 (3.7%) | 7 (13.2%) | 0.039 |

| Severity of illness | |||

| Pneumonia | 37 (90.1%) | 4 (0.9%) |

<0.001** |

| Pneumosepsis | 36 (69.2%) | 16 (30.8%) | |

| Septic shock | 9 (21.4%) | 33 (78.6%) |

| Laboratory Findings | All Patients (N=135) Median (IQR 25–75) |

Survivors (N=82) Median (IQR 25–75) |

Deceased (N=53) Median (IQR 25–75) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 51 (9.40–141.00) | 62.86 (10.37–136.25) | 32.20 (8.80–148.00) | 0.456 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.30 (0.12–0.92) | 0.19 (0.06–0.67) | 0.46 (0.21–2.63) | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.00 (2.60–3.50) | 3.20 (2.70–3.50) | 2.90 (2.40–3.40) | 0.006 |

| Neutrophils (˟10³/µL) | 10.20 (7.57–14.30) | 9.92 (7.35–14.07) | 10.60 (7.65–15.70) | 0.620 |

| Neutrophil percentage | 86.80 (79.60–91.80) | 85.00 (78.02–90.90) | 89.00 (85.00–92.60) | 0.004 |

| NPAR* | 3.21 (2.55–25.80) | 2.91 (2.44–21.60) | 4.22 (2.98–30.92) | <0.001 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 60 (36–90) | 51 (34–75) | 82 (54.50–108) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.29 (1.00–1.95) | 1.13 (0.89–1.76) | 1.52 (1.18–2.10) | 0.010 |

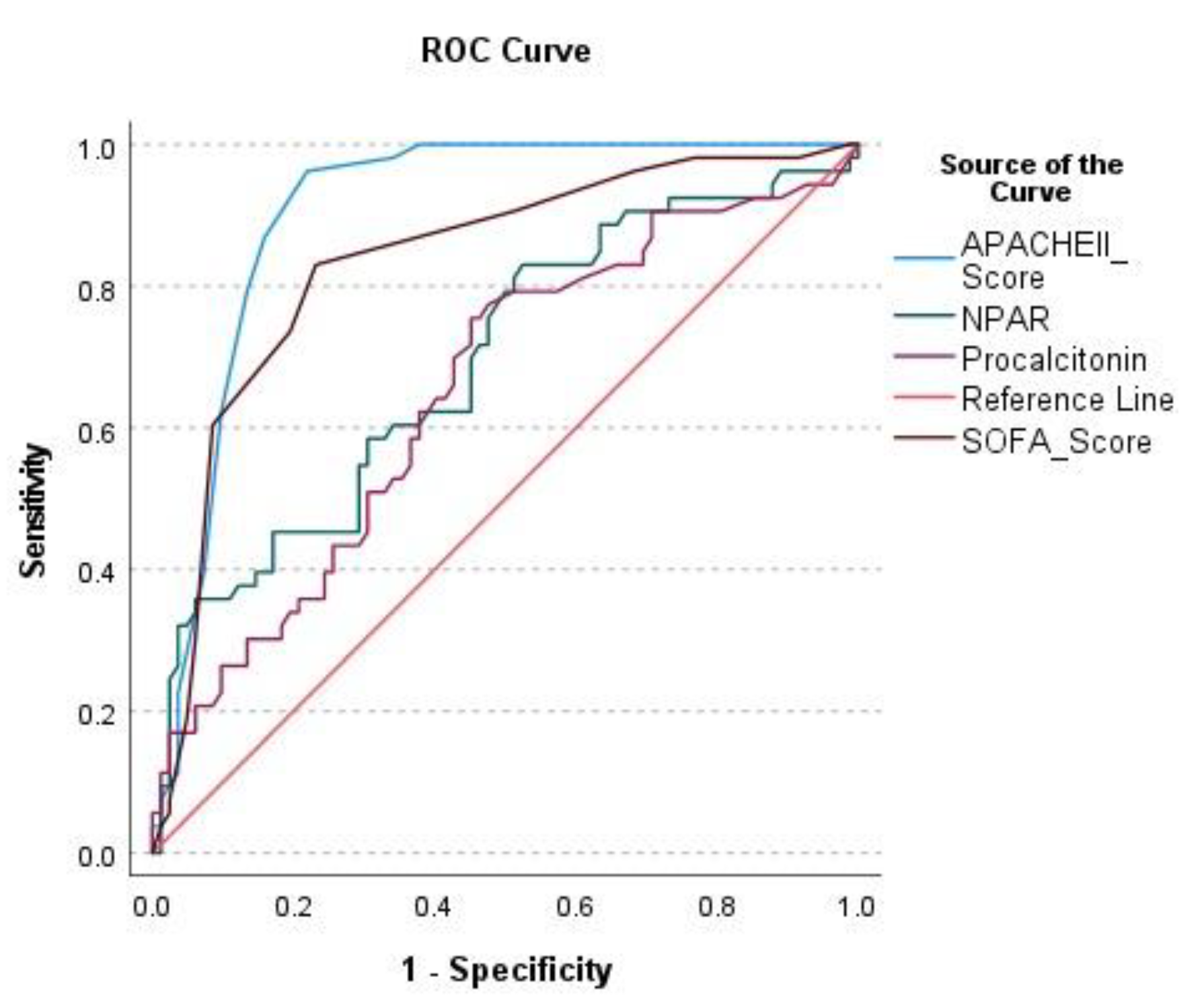

| AUC | 95% Confidence Interval | Cut-Off Value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR- | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APACHE II | 0.905 | 0.853–0.957 | 23.50 | 96.2 | 78.0 | 73.9 | 97.0 | 4.38 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

| SOFA | 0.834 | 0.762–0.906 | 6.50 | 83.0 | 76.8 | 69.8 | 87.5 | 3.58 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| NPAR* | 0.692 | 0.599–0.784 | 2.86 | 83.0 | 47.6 | 50.6 | 81.2 | 1.58 | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Procalcitonin | 0.652 | 0.557–0.747 | 0.21 | 75.5 | 54.9 | 51.9 | 77.6 | 1.67 | 0.45 | 0.002 |

| Variable | Univariate Cox Regression | Multivariate Cox Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Presence of resistant bacteria in culture | 1.447 (0.802–2.610) | 0.219 | - | - |

| Presence of comorbidities | 2.290 (0.911–5.760) | 0.078 | - | - |

| COPD* | 1.765 (1.022–3.046) | 0.041 | 2.069 (1.162–3.684) | 0.014 |

| Malignancy | 2.456 (1.105–5.460) | 0.028 | 1.824 (0.801–4.152) | 0.152 |

| NPAR** | 1.035 (1.016–1.055) | <0.001 | 1.040 (1.021–1.060) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).