1. Introduction

Population aging is a now evident global phenomenon and one of the most significant challenges of our century. According to WHO estimates, the number and percentage of people aged 65 and over are increasing. This increase is occurring at an unprecedented rate and will accelerate in the coming decades, worldwide. In 2019, the number of people aged 65 and over was 1 billion. By 2030, 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged 65 or over. By 2050, the global population of people aged 65 and over will double (2.1 billion). The number of people aged 80 and over is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050, reaching 426 million. While population ageing has been a reality for many years in high-income countries (e.g., Western Europe, the United States, and Japan), currently emerging economies are experiencing the most significant change. By 2050, it is estimated that two-thirds of the world's population aged 65 and over will live in low- and middle-income countries. [

1]

This will lead to a subsequent increase in the number of people affected by several chronic pathologies, or by the well-known geriatric syndrome which is frailty. By frailty, we mean the state of greater vulnerability, or reduced resilience, in response to a stressful event, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes, including falls, delirium, and disability [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], along with a significant rise in care burden and expenses due to hospitalizations [

8,

9,

10].

Elderly people, in particular frail elderly people, hospitalized in acute hospital departments already suffer from chronic diseases, with signs and symptoms of physical and cognitive deterioration, malnutrition and in complex home therapies characterized by the intake of numerous drugs [

11]. Malnutrition is a high-risk condition for the development of frailty, where malnutrition refers to a broad group of conditions, including undernutrition (wasting, stunting and underweight), inadequate intake of vitamins or minerals, as well as overweight and obesity, resulting in diet-related non-communicable diseases [

12]. In addition, hospitalized older patients can show a high rate of short- and long-term mortality [

13].

In acutely ill patients, disease-related malnutrition may occur due to a catabolic state triggered by systemic inflammation secondary to a concomitant disease.

Malnutrition prevalence among in-hospital patients ranges between 15% and 70% [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Several factors may contribute to malnutrition, such as underlying illnesses, aging, socioeconomic situations, as well as in-hospital medical procedures that impact food intake, lack of monitoring of the nutritional status, and lack of standardized nutrition care protocols [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Independently of other factors, malnutrition at admission among hospitalized patients is one of the most important negative predictors influencing the risk of increased incidence of complications (e.g., infections, pressure ulcers), as well as higher length of stays (LOS) in hospital, higher readmission rates, poor treatment outcomes of the primary disease and comorbidities, higher healthcare costs, and increased patient mortality [

26,

27,

28,

29].

Albumin is an acute-phase protein, synthesized by the liver, and has several key functions: It is the primary serum binding protein responsible for the transport of various substances, e.g., fatty acids, hormones, and drugs. Especially in the elderly, this is important, as the concentration of unbound drugs in the circulation is increased, and the increased bioavailability may lead to adverse effects in hypoalbuminemia. [

30].

Albumin also has an anti-thrombotic effect, and it is essential in the maintenance of normal plasma colloid oncotic pressure. Normally, albumin has a long half-life (15–19 days), but the plasma albumin can fall by 10–15 g/L in 3 to 5 days in critically ill patients.

Hypoalbuminemia has previously been associated with increased short-term mortality, length of hospital stays, and complications in in-hospital patients. [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]

Serum albumin levels are also a well-known marker in the measurement of malnutrition. Hypoalbuminemia, which is remarkably prevalent in elderly population, has already been identified as an unfavourable prognostic marker [

37,

38].

Serum albumin levels are indicative of the sum of hepatic synthesis (12–15 g/day), plasma distribution, and protein loss [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

Results from a previous large cohort study have shown that hypoalbuminemia is associated with increased 30-day all-cause mortality in acutely admitted medical patients. Serum values of albumin can be used as a predictive tool for mortality, with an acceptable discriminatory power, as vital signs, or a combination of other blood tests [

50].

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a cheap, easy, and rapid inflammatory marker; it can be a proper predictor of mortality. Measuring CRP at hospital admission may help identify patients at increased risk of adverse outcomes, such as both short- and long-term mortality risk [

51,

52,

53,

54]. It is known that elevated levels of CRP are associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality [

55,

56,

57], that is, even a single measurement of plasma CRP is significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, while no association has been observed between genetically elevated levels of CRP and risk of mortality. Elevated levels of CRP may constitute an important indicator of a latent inflammatory disease, which, the latter certainly, could lead to early death [

58].

It is therefore evident that CRP and serum albumin (Alb) are useful markers for predicting morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients [

59,

60], since CRP is an effective marker of acute inflammation [

61,

62], while serum albumin (Alb) is an effective indicator of malnutrition status in critically ill patients [

63,

64]. The CRP/Alb ratio has also recently been used to predict the prognosis of patients with severe sepsis or septic shock [

65,

66], where an elevated CRP/Alb ratio at admission may be associated with a higher mortality rate in adult patients with sepsis (The prognostic value of the C-reactive protein to albumin ratio in patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis). Furthermore, a high CRP/Alb ratio at ICU admission, for example, in patients with severe burns, is independently and significantly associated with increased mortality rates, i.e., lower 30-day survival post-burn [

67]

CRP/Alb ratio has also been shown to be a useful prognostic marker in non-septic or otherwise non-infectious patients, for example in patients with heart failure, where a previous study showed that a high CRP/Alb ratio is significantly associated with high in-hospital and out-of-hospital all-cause mortality in patients with acute and chronic heart failure. A high CRP/ALB ratio is associated with frequent and repeated hospital admissions, as well as a higher risk of developing severe heart failure [

68]. Therefore, the CRP/ALB ratio may be useful for the assessment of critically ill patients, as it effectively reflects both inflammation and malnutrition [

69,

70]. In other words, a high CRP/ALB ratio at admission may be independently associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality, as demonstrated by a previous study. However, the same study did not identify the CRP/ALB ratio as a useful marker in predicting 30-day mortality in critically ill patients, compared to other prognostic factors such as APACHE II or Charlson Comorbidity Index [

71,

72].

Considering also patients who are not necessarily critically ill, the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, together with the mid-upper arm circumference and the assessment of impaired self-nutrition, are easily obtainable indicators of an altered energy and protein intake and poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized older people [

73]. This means that the CRP/ALB ratio, assessing both inflammation and malnutrition with a cost-effectiveness ratio, could represent a useful additional parameter for the risk stratification of hospital mortality in older patients, independently of the diagnosis, although it seems that this association is stronger in men than in women [

74,

75].

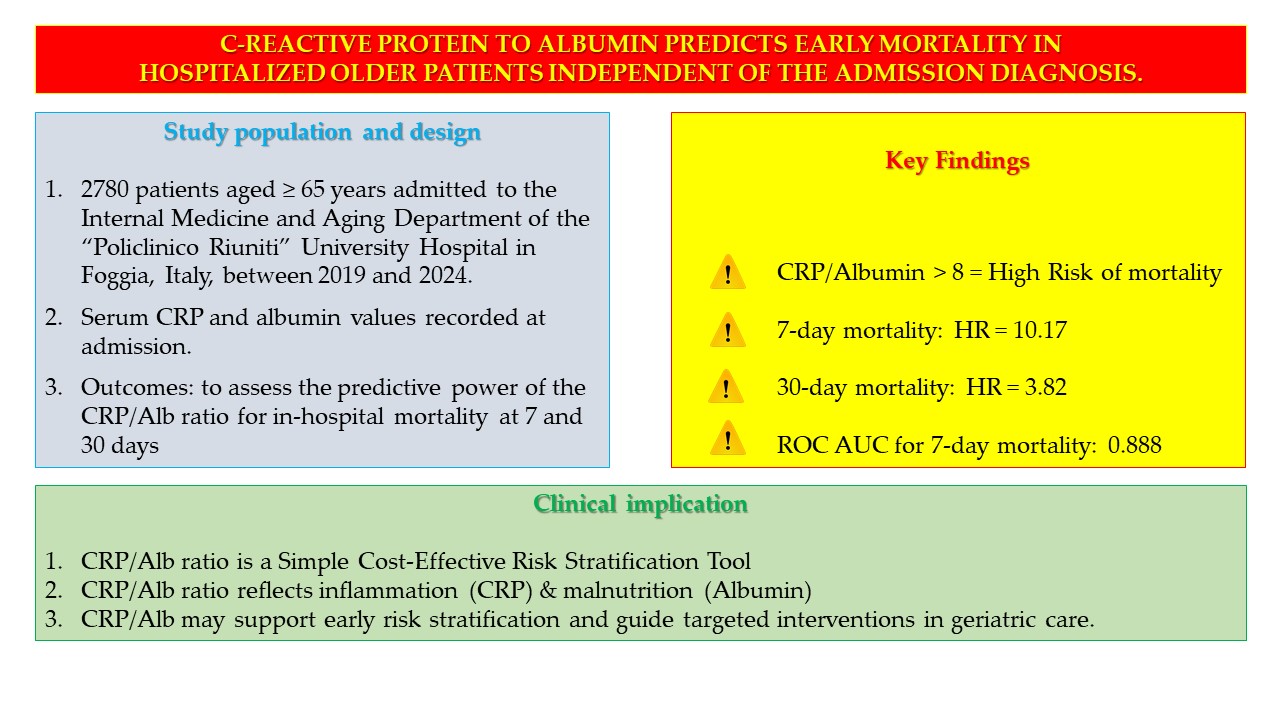

We conducted an observational, retrospective study on a cohort of elderly patients admitted to an internal and aging medicine department at the “Policlinico Riuniti” University Hospital of Foggia, Italy to assess the prognostic value of the CRP/Alb ratio in predicting the risk of in-hospital mortality during the first 7 days and after 30 days of hospitalization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

We examined a cohort of 3571 elderly patients admitted to the Internal Medicine and Aging Department of the “Policlinico Riuniti” University Hospital in Foggia, Italy, between 1 January 2019, and 31 December 2024. Study exclusion criteria were age less than 65 years at the time of admission; patients discharged against medical advice; patients transferred to other departments or other hospitals; and patients discharged to nursing homes or rehabilitation institutions. The final cohort consisted of 2780 subjects.

2.2. Methods

Serum values of C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum albumin, length of stay (LOS), and outcome of hospitalization, i.e., discharge home or death and were recorded from all patients. We must underline that all patients analysed in our study were treated with medical therapy. In some cases, the therapy they were already taking at home had been confirmed in whole and in part; in others, the therapy had been modified depending on the clinical situation.

2.3. Statistics

After performing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and having verified from the test that all the data examined did not follow the normal distribution (p < 0.001), the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test corrected with the Monte Carlo exact test for the comparison of means for independent samples was performed; also, the non-parametric Spearman test for the calculation of correlations was performed.

Analysis of the ROC curve was also performed to measure the sensitivity and specificity, or the predictive value of mortality of CRP/Alb ratio, as well as to identify the optimal thresh-old value (best cut-off). We used Cox regression in survival analysis in the prediction of mortality, expressed by the Hazard Ratio (HR), Both ROC curve and Cox regression were performed after correction for sex.

Finally, the Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to estimate the survival of patients during the observation period, in relation to the examined parameters. The Log-rank test, stratified by age at admission, was performed to compare the two Kaplan–Meier survival curves.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (Armonk, NY, USA), and STATA SE 14.2 (College Station, TX, USA), with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

The features of the sample examined are presented in

Table 1. Women were more represented than men (p = 0.005). As expected, women were older than men (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were observed between men and women for both LOS and serum values Albumin. Men had higher CRP values (p = 0.006), and higher CRP/Alb ratio values than women (p = 0.006).

As shown in

Table 2, after correcting by sex, the correlation analysis showed, a direct relationship between CRP values and CRP/Alb ratio and LOS (p < 0.001), and an inverse relationship between Albumin values and LOS (p < 0.001), as expected, were observed; no statistically significant correlation was observed between age at admission and LOS (p = 0.441).

Four hundred and forty-four patients died during hospitalization. The main causes of death are reported in

Table 3. According to previous studies, and according to data collected by the Italian National Cause of Death Register, managed by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) [

76,

77] severe sepsis is the most frequent cause of in-hospital death. As shown in

Table 4, the deceased were older than the not deceased (p < 0.001), with no significant differences between males and females (p = 0.276), and in terms of LOS (p = 0.368). Deceased patients had lower albumin, higher CRP levels, and higher CRP/Alb ratio (p < 0.001) compared to non-deceased patients.

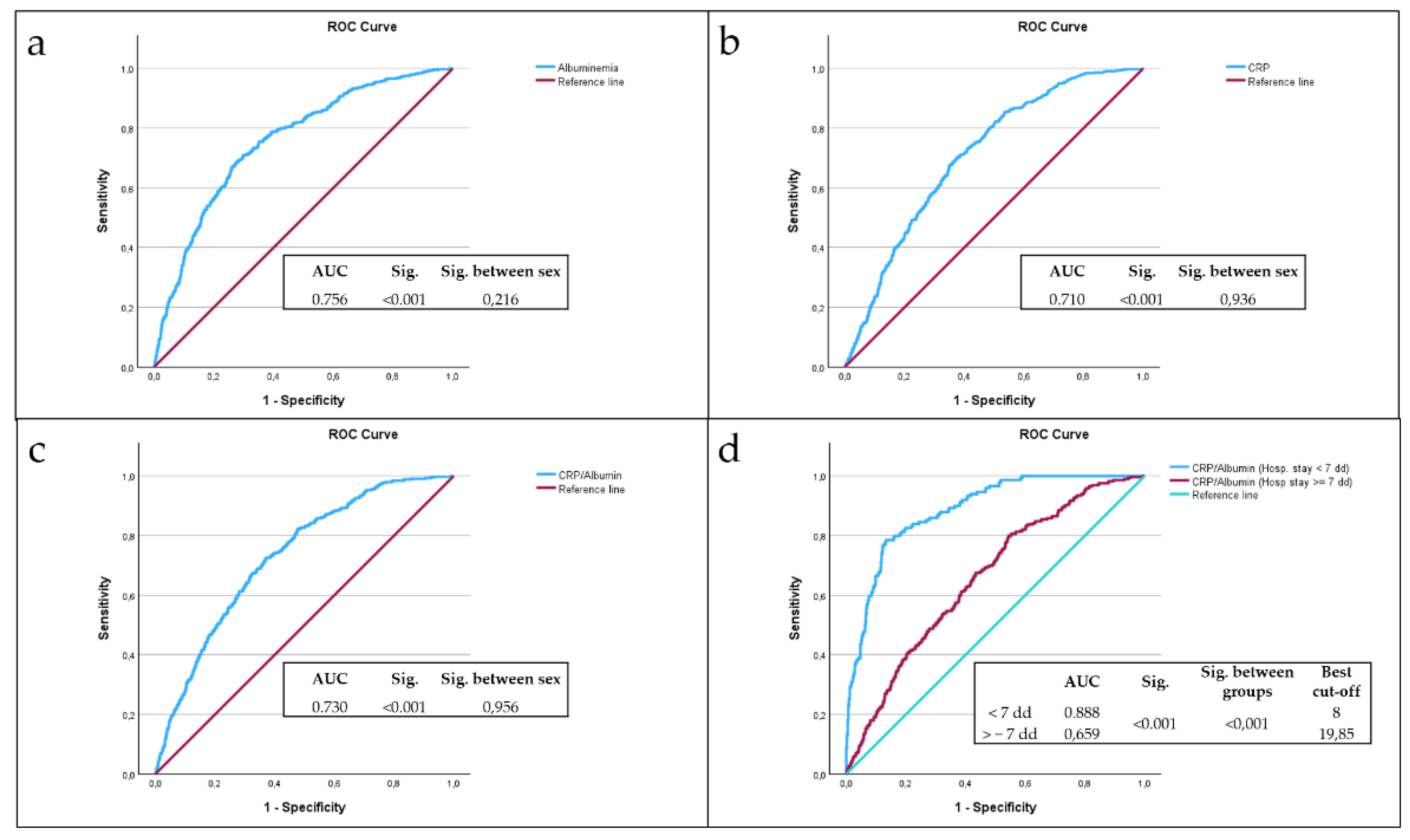

The analysis of the ROC curves showed that albumin (

Figure 1a), CRP (

Figure 1b) and CRP/Alb ratio (

Figure 1c) are significant predictors of mortality. Comparing the area under the curve (AUC), the most accurate predictor of mortality is albumin, with an AUC of 0.756, without any difference between sex (p = 0.216); CRP showed an AUC of 0.710 without any difference between sex (p = 0.936). CRP/Alb ratio showed an AUC of 0.730, without any difference between sex (p = 0.956). After dividing the sample by hospital stay days, i.e. by hospital stay days less than seven days or equal to or greater than seven days, CRP/Alb ratio among subjects with hospital stays of less than seven days is a more accurate predictor of mortality than subjects with hospital stays of equal to or greater than seven days (p < 0.001), with an AUC of 0.888 and the best cut-off of 8 (

Figure 1d).

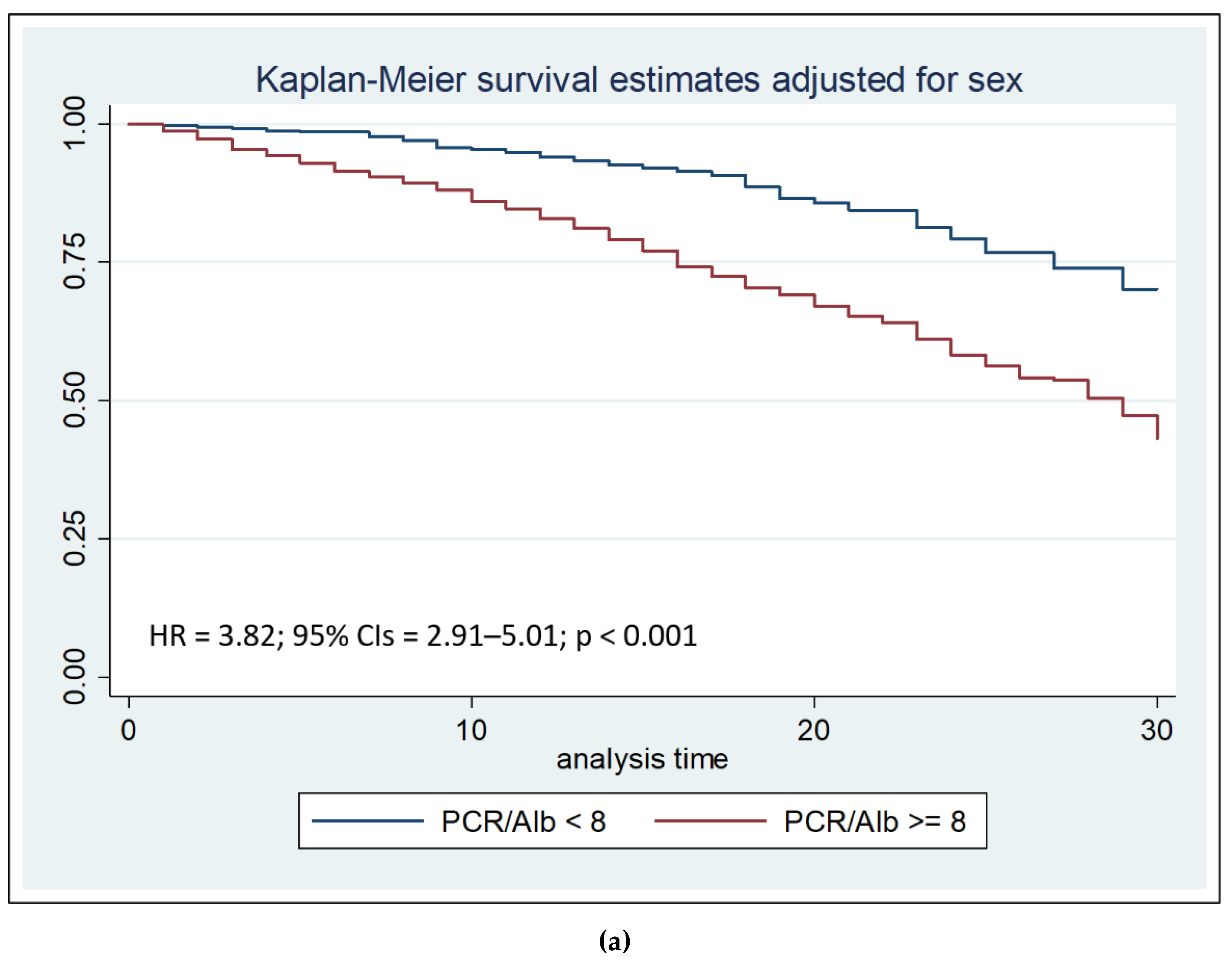

After correcting for sex and hospital stay days less or equal to or greater than seven days, the Cox regression analysis with the Breslow method was performed. The result of the analysis highlighted that the CRP/Alb ratio more than 8 is an independent risk factors for mortality during the first thirty days of hospitalization (HR = 3.82, 95% Confidence Intervals = 2.91–5.01, p < 0.001) (

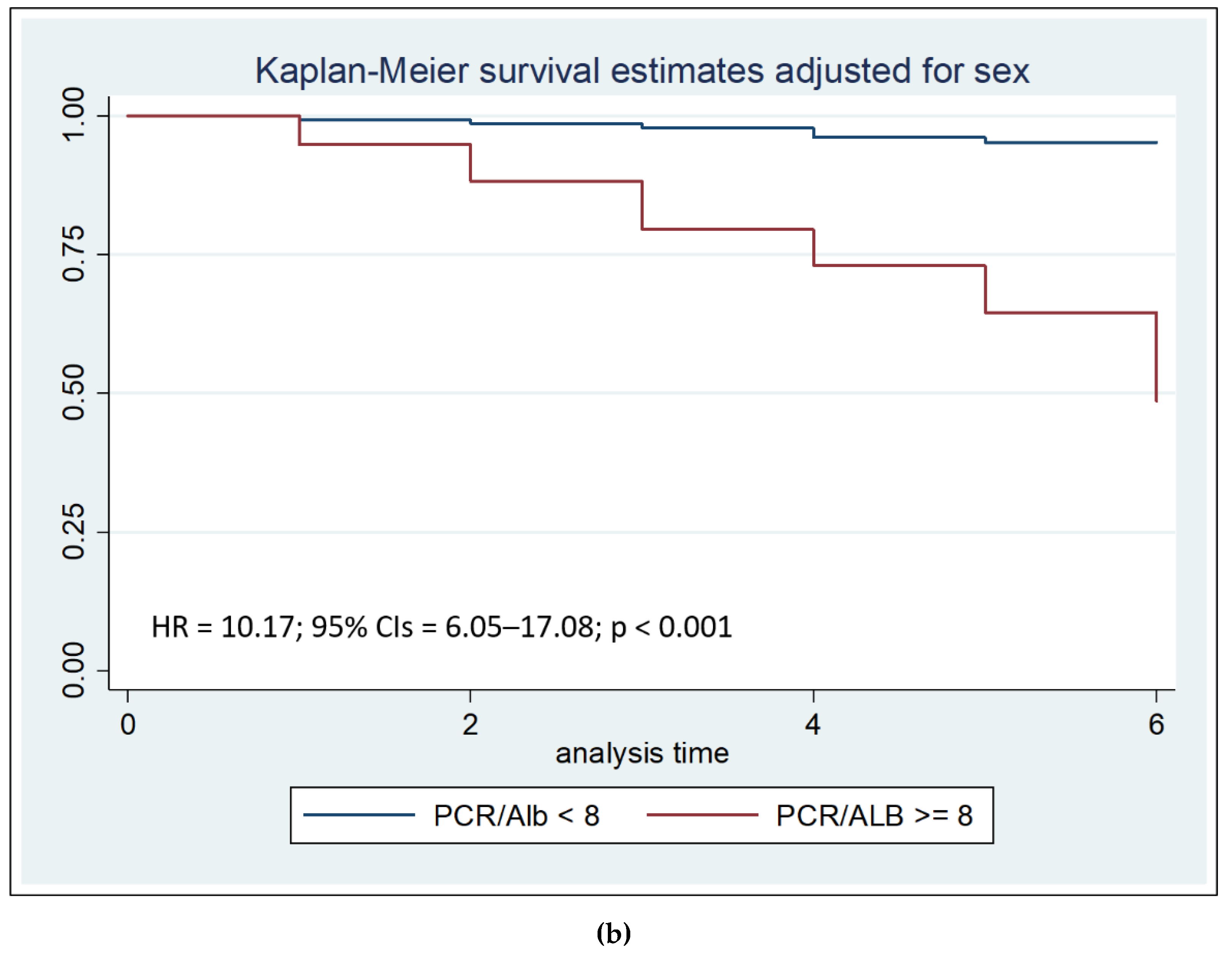

Figure 2a). Particularly, a CRP/Alb ratio of more than 8 is a strong independent risk factor for mortality during the first seven days of hospitalization (HR = 10.17, 95% Confidence Intervals = 6.05–17.08, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2b).

We then performed survival analysis using the Log-rank test, stratified by sex, to compare the two Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Survival analysis showed that both after thirty days than after seven days from admission, CRP/Alb ratio more than 8 was associated with reduced survival (p < 0.001).

Finally, for 370 patients, the hospitalization was a rehospitalization, that is, a new hospitalization within thirty days of a previous discharge. Concerning these patients, a CRP/Alb ratio more than 8 constituted a significant risk factor for of mortality, particularly during the first seven days of hospitalization, as shown in

Table 5 (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The present study offers important insights into the predictive value of the C-reactive protein to albumin (CRP/Alb) ratio for early mortality among hospitalized older adults, independent of their admission diagnosis. In a context where hospital mortality and rehospitalization are prevalent and burdensome, especially among patients over 65 years of age, the findings underscore the clinical utility of a simple, accessible biomarker that captures both inflammatory and nutritional status.

Malnutrition and systemic inflammation are widely recognized as independent risk factors for adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients. In the geriatric population, these conditions are even more critical due to the complex interplay between chronic comorbidities, frailty, and diminished physiological reserves. The literature has consistently highlighted the role of hypoalbuminemia as a marker of malnutrition and poor prognosis [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

50], as well as the role of elevated CRP as an indicator of acute or chronic inflammation and mortality risk [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

74].

This study analyzed a large, homogeneous cohort of elderly patients (n = 2780), which is a major strength. All participants were aged 65 years and older, eliminating the confounding impact of younger, potentially more resilient individuals. With 444 deaths recorded during hospitalization (16% of the sample), the study provides robust data to support the association between baseline CRP/Alb ratios and early in-hospital mortality.

The results showed that deceased patients had significantly higher CRP and lower albumin levels compared to survivors. The CRP/Alb ratio was higher in deceased patients, confirming the ratio’s ability to reflect a state of combined inflammation and malnutrition. These findings align with previous studies that have identified the CRP/Alb ratio as a significant predictor of poor outcomes in critically ill and elderly patients [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

69,

70].

The ROC curve analysis demonstrated that while both albumin and CRP independently predicted mortality, the CRP/Alb ratio had a comparable AUC (0.730) to albumin alone (0.756) and was slightly more accurate than CRP (AUC = 0.710). Notably, when analyzing patients with hospital stays under seven days, the CRP/Alb ratio’s predictive accuracy increased substantially, with an AUC of 0.888. This supports the hypothesis that CRP/Alb is particularly useful in identifying patients at risk of early mortality—a critical insight for acute care management.

Furthermore, Cox regression analysis confirmed that a CRP/Alb ratio >8 was an independent predictor of mortality within 30 days, and especially within the first 7 days (HR = 10.17, p < 0.001). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis reinforced these findings by demonstrating significantly lower survival rates in patients with a CRP/Alb ratio greater than 8, both at 7 and 30 days after admission. These results are consistent with previous research showing the CRP/Alb ratio's ability to predict early outcomes in various patient populations, including those with sepsis, burns, and cardiac conditions [

65,

66,

67,

68].

Beyond the predictive value of CRP/Alb, the study’s design and population allow us to generalize the findings to the broader aging inpatient population. As the global population continues to age, projected to double in the next two decades [

1], health systems must find reliable tools for early risk stratification. A biomarker that is both inexpensive and quickly obtainable, such as the CRP/Alb ratio, fits well into this model of predictive, proactive care.

One of the key implications of this study is the reinforcement of the idea that malnutrition and inflammation are not merely secondary considerations in acute care—they are fundamental to outcomes. The bidirectional relationship between inflammation and nutrition is well established; systemic inflammation promotes protein catabolism and reduces albumin synthesis, while malnutrition impairs immune function, exacerbating inflammation. The CRP/Alb ratio, by capturing both dimensions, provides a more holistic risk assessment than either marker alone.

The study also offers valuable data regarding rehospitalized patients. Among the 370 patients readmitted within 30 days, a CRP/Alb ratio >8 was again associated with significantly higher early mortality. This supports existing literature showing that patients with poor nutritional and inflammatory profiles at the time of discharge are at increased risk of adverse outcomes upon readmission [

73,

74].

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First and foremost, the retrospective nature of the study imposes inherent limitations regarding causality. Although strong associations are observed, it is not possible to determine whether changes in CRP/Alb levels directly influence outcomes or merely reflect underlying disease severity. Furthermore, only laboratory values collected at the time of admission were included in the analysis. Data on CRP and albumin at discharge or near death—potentially more informative in understanding the progression of illness—were not available. Future studies would benefit from serial measurements to examine dynamic changes in the CRP/Alb ratio and their relation to treatment response and recovery.

Another limitation is the absence of detailed comorbidity data, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index or APACHE II scores, which could offer a more nuanced understanding of the predictive power of CRP/Alb compared to established clinical indices. While our data did adjust for sex and length of stay, other potential confounders such as medication use, primary diagnoses, and functional status were not included in the regression models.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes meaningfully to a growing body of literature advocating for the use of simple biochemical markers in risk stratification. In clinical practice, particularly in resource-limited settings, the ability to assess mortality risk using routinely collected data is highly advantageous. The CRP/Alb ratio provides such a tool and could be incorporated into early assessment protocols for elderly patients admitted to internal medicine wards.

Our findings align with those of a previous study, which confirmed that CRP and albumin-based inflammation scores are independent predictors of mortality in older adults across a wide range of diagnoses [

74]. Moreover, this study emphasizes the need for systematic nutritional assessment at the time of hospitalization, echoing ESPEN guidelines on the importance of early and accurate nutritional screening [

4]. Interventions such as early nutritional supplementation, anti-inflammatory treatment, or closer monitoring could be guided by CRP/Alb-based stratification.

It is also important to consider the potential for sex-based differences in biomarker interpretation. While this study did not observe a statistically significant difference in CRP/Alb predictive capacity between men and women, previous work has suggested sex-specific inflammatory responses and outcomes [

75]. Further research with sex-disaggregated data could provide more detailed insights.

In conclusion, this study reinforces the role of CRP/Alb ratio as a significant, independent predictor of short-term mortality in elderly hospitalized patients. It also suggests that this marker may be especially valuable for identifying those at risk of early death during short hospital stays or in the context of rehospitalization. While prospective validation is required, the simplicity and accessibility of CRP and albumin testing make their ratio an attractive candidate for widespread clinical implementation.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective study on a large and homogeneous cohort of elderly inpatients confirms the prognostic value of the CRP/albumin ratio in predicting early in-hospital mortality. The CRP/Alb ratio, which reflects the dual impact of inflammation and malnutrition, emerged as an independent risk factor for mortality during hospitalization, with particularly high predictive power within the first seven days of admission. A threshold value of 8 for the CRP/Alb ratio was identified as a strong discriminator of risk.

The strengths of this study include its large sample size and the homogeneity of the population, limited to patients aged 65 and above, which enhances its applicability to geriatric care. However, its retrospective nature and reliance on admission-only laboratory data are notable limitations. The lack of discharge or pre-mortem values limits the capacity to track biomarker evolution and treatment response.

Despite these limitations, the findings underscore the clinical utility of the CRP/Alb ratio as a simple, cost-effective tool for early mortality risk stratification in elderly hospitalized patients. Future prospective studies with serial biomarker measurements and more detailed clinical data are warranted to validate these findings and integrate the CRP/Alb ratio into comprehensive geriatric assessment protocols. Integrating this biomarker into routine evaluation could support timely interventions and improve outcomes in a rapidly aging patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., A.L.B. and F.B.; methodology, C.C. and A.L.B.; software, C.C..; validation, G.S.; formal analysis, C.C. and F.B.; investigation, C.C.; data curation, C.C.; writing and original draft preparation, C.C.; writing and review and editing, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Policlinico Riuniti di Foggia (protocol code 161/2023, approval date 23 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cereda, E.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; de Groot, L.; Großhauser, F.; Kiesswetter, E.; Norman, K.; et al. Management of Malnutrition in Older Patients—Current Approaches, Evidence and Open Questions. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanson, G.; Bertocchi, L.; Dal Bo, E.; Di Pasquale, C.L.; Zanetti, M. Identifying reliable predictors of protein-energy malnutrition in hospitalized frail older adults: A prospective longitudinal study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walston, J.; Hadley, E.C.; Ferrucci, L; Guralnik, J.M.; Newman, A.B.; Studenski, S.A.; Ershler, W.B.; Harris, T.; Fried, L.P. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: Toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 991–1001.

- Eeles, E.M.; White, S.V.; O’Mahony, S.M.; Bayer, A.J.; Hubbard, R.E. The impact of frailty and delirium on mortality in older inpatients. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Morsiani, C.; Conte, M; Santoro, A.; Grignolio, A.; et al. The Continuum of aging and age-related diseases: common mechanisms but different rates. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018, 5, 61.

- Pisano, C.; Polisano, D.; Balistreri, C.R.; Altieri, C.; Nardi, P.; Bertoldo, F.; et al. Role of cachexia and fragility in the patient candidate for cardiac surgery. Nutrients. 2021, 13(2), 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C.; Ho, F.K. Frailty, sarcopenia, cachexia and malnutrition as comorbid conditions and their associations with mortality: a prospective study from UK Biobank. J Public Health (Oxf ). 2022, 44(2), e172–80.

- Slee, A.; Birch, D.; Stokoe, D. The relationship between malnutrition risk and clinical outcomes in a cohort of frail older hospital patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2016, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Lee, S.B.; Oh, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Choi, S.P.; Wee, J.H. Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2018, 5(4), 249–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigoz, Y. The mini nutritional assessment (MNA) review of the literature e what does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging 2006, 10(6), 466–85. discussion 485–7.

- Pirlich, M.; Schutz, T.; Norman, K.; Gastell, S.; Lubke, H.J.; Bischoff, S.C.; et al. The German hospital malnutrition study. Clin Nutr 2006, 25(4), 563–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, M.; Ash, S.; Bauer, J.; Gaskill, D. Prevalence of malnutrition in adults in Queensland public hospitals and residential aged care facilities. Nutr Diet 2007, 64(3), 172–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrup, J.; Sorensen, J.M. The magnitude of the problem of malnutrition in Europe. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Clin Perform Program 2009, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Waitzberg, D.L.; Caiaffa, W.T.; Correia, M.I.T.D. Hospital malnutrition: the Brazilian national survey (IBRANUTRI): a study of 4000 patients. Nutrition 2001, 17(7–8), 573–80.

- Aghdassi, E.; McArthur, M.; Liu, B.; McGeer, A.; Simor, A.; Allard, J.P. Dietary intake of elderly living in Toronto long-term care facilities: comparison to the dietary reference intake. Rejuvenation Res 2007, 10(3), 301–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Watt, K.; Veitch, R.; Cantor, M.; Duerksen, D.R. Malnutrition is prevalent in hospitalized medical patients: are housestaff identifying the malnourished patient? Nutrition 2006, 22(4), 350–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalon, L.; Laporte, M.; Carrier, N. Nutrition screening for seniors in health care facilities: a survey of health professionals. Can J Diet Pract Res 2011, 72(4), 162–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirlich, M.; Schutz, T.; Kemps, M.; Luhman, N.; Minko, N.; Lubke, H.J.; et al. Social risk factors for hospital malnutrition. Nutrition 2005, 21(3), 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, T.F.; Matos, L.C.; Teixeira, M.A.; Tavares, M.M.; Alvares, L.; Antunes, A. Undernutrition and associated factors among hospitalized patients. Clin Nutr 2010, 29(5), 580–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrup, J.; Johansen, N.; Plum, L.M.; Bak, L.; Larsen, I.H.; Martinsen, A.; et al. Incidence of nutritional risk and causes of inadequate nutritional care in hospitals. Clin Nutr 2002, 21(6), 461–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, J.P.; Keller, H.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N.; Laporte, M.; Duerksen, D.R.; Gramlich, L.; et al. Decline in nutritional status is associated with prolonged length of stay in hospitalized patients admitted for 7 days or more: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Nutrition 2016, 35, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, M.L.; Morley, J.E. Evaluation of protein-energy malnutrition in older people, Part II: Laboratory evaluation. Nutrition 2000, 16, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrie, E.; Lew, N. Death risk in hemodialysis patients: The predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1990, 15, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Renal Data System. Combined conditions and correlation with mortality risk among 3399 incident hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1992, 20 (Suppl. 2), 32.

- Guijarro, C.; Massy, Z.A.; Wiederkehr, M.R.; Ma, J.Z.; Kasiske, B.L. Serum albumin and mortality after renal transplantation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1996, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tal, S.; Guller, V.; Shavit, Y.; Stern, F.; Malnick, S. Mortality predictors in hospitalized elderly patients. Quarterly Jour of Medicine. 2011, 104(11), 933–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, O., Whelan, B.; Bennett, K.; O’Riordan, D.; Silke, B. Serum albumin as an outcome predictor in hospital emergency medical admissions. Eur J Int Med. 2010, 21, 17–20.

- Marik, P.E. The treatment of hypoalbuminemia in the critically ill patient. Heart Lung. 1993 22: 166–70.

- Haller, C. Hypoalbuminemia in Renal Failure. Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Considerations. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2005, 28, 307–310. [CrossRef]

- Namendys-Silva, S.A.; Gonzalez-Herrera, M.O. Herrera-Gomez, A. Hypoalbuminemia in Critically Ill patients With Cancer: Incidence and Mortality. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2011, 28(4), 253–257.

- Oster, H.S.; Dolev, Y.; Kehat, O.; Weis-Meilik, A.; Mittelman, M. Serum Hypoalbuminemia Is a Long-Term Prognostic Marker in Medical Hospitalized Patients, Irrespective of the Underlying Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akirov, A.; Masri-Iraqi, H.; Atamna, A.; Shimon, I. Low Albumin Levels Are Associated with Mortality Risk in Hospitalized Patients. The American Journal of Medicine. 2017, 130, 1465.e11–1465e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwasser, P.; Feldman, J. Association of serum albumin and mortality risk. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, I.; Dupuy, A-M.; Lacroux, A.; Cristol, J-P.; Delcourt, C.; and the Pathologies Oculaires Liees a l’Age Study Group. Biomarkers of Inflammation and Malnutrition Associated with Early Death in Healthy Elderly People. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008, 56, 840–846.

- Omran, M.L.; Morley, J.E. Evaluation of protein-energy malnutrition in older people, Part II: Laboratory evaluation. Nutrition. 2000, 16, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrie, E.; Lew, N. Death risk in hemodialysis patients: The predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1990, 15, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Renal Data System. Combined conditions and correlation with mortality risk among 3399 incident hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1992, 20 (Suppl. 2), 32.

- Guijarro, C.; Massy, Z.A.; Wiederkehr, M.R.; Ma, J.Z.; Kasiske, B.L. Serum albumin and mortality after renal transplantation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1996, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Draper, E.A.; Zimmerman, J.E.; Bergner, M.; Bastos, P.G.; Sirio, C.A.; Murphy, D.J.; Lotring, T.; Damiano, A.; et al. The APACHE III prognostic system-risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991, 100, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A.; Shaper, A.G.; Whincup, P.H. Association between serum albumin and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes. Lancet. 1989, 2, 1434–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillum, R.F.; Makuc, D.M. Serum albumin, coronary heart disease, and death. Am. Heart J. 1992, 123, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Barrett-Connor, E.L.; Edelstein, S.L. Albumin levels as a predictor of mortality in the healthy elderly. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corti, M.C.; Guralnik, J.M.; Salive, M.E.; Sorkin, J.D. Serum albumin level and physical disability as predictors of mortality in older persons. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994, 272, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.R.; Morris, J.K.; Wald, N.J.; Hale, A.K. Serum albumin and mortality in the BUPA study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 23, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, L.H.; Eichner, J.E.; Orchard, T.J.; Grandits, G.A.; McCallum, L.; Tracy, R.P. The relation between serum albumin and risk of coronary heart disease in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991, 134, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, S.; Cuadras, D.; Gomez-Busto, F.; Artaza-Artabe, I.; Marin-Ciancas, F.; Malafarina, V. Serum albumin and health in older people: review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2015, 81(1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devran, Ö.; Karakurt, Z.; Adıgüzel, N.; Güngör, G.; Moçin, Ö.Y.; Balcı, M.K.; et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of mortality in patients affected with severe sepsis in intensive care unit. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine 2012, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, S.M.; Lobo, F.R.; Bota, D.P.; Lopes-Ferreira, F.; Soliman, H.M.; Mélot, C.; Vincent, J.L. C-reactive protein levels correlate with mortality and organ failure in critically ill patients. Chest 2003, 123, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.F.; Kilstein, J,; Bagilet, D,; Pezzotto, S.M. C-reactive protein as a marker of mortality in intensive care unit. Med Intensiva 2008, 32, 424–430.

- Marsik, C.; Kazemi-Shirazi, L.; Schickbauer, T.; Winkler, S.; Joukhadar, C.; Wagner, O.F.; Endler, G. C-Reactive Protein and All-Cause Mortality in a Large Hospital-Based Cohort. Clinical Chemistry 2008, 54(2), 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.J.; Arnold, A.M.; Manolio, T.A.; Polak, J.F.; Psaty, B.M.; Hirsch, C.H.; Kuller, L.H.; Cushman, M. Association of carotid artery intima-media thickness, plaques, and C-reactive protein with future cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2007, 116, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.J.; Poole, C.D.; Conway, P. Evaluation of the association between the first observation and the longitudinal change in C-reactive protein, and all-cause mortality. Heart 2008, 94, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacho, J.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. C-reactive protein and all-cause mortality—the Copenhagen City Heart Study. European Heart Journal 2010, 31, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinge, M.E.; Henriksen, D.P.; Hallas, P.; Brabrand, M. Hypoalbuminemia Is a Strong Predictor of 30-Day All-Cause Mortality in Acutely Admitted Medical Patients: A Prospective, Observational, Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9(8), e105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devran, O.; Karakurt, Z.; Adiguzel, N.; Gungor, G.; Mocin, O.Y.; Balci, M.K.; Celik, E.; Salturk, C.; Takir, H.B.; Kargin, F.; et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of mortality in patients affected with severe sepsis in intensive care unit. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2012, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, E.A.; Li, X.M.; Yi, H. Comparison and relationship of thyroid hormones, il-6, il-10 and albumin as mortality predictors in case-mix critically ill patients. Cytokine 2016, 81, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povoa, P. C-reactive protein: A valuable marker of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2002, 28, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.K.; Ji, E.; Na, H-s.; Min, B.; Jeon, Y-T.; Do S-H.; Song, I-A.; Park, H-P.; Hwang, J-W. C-Reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio Predicts 30-Day and 1-Year Mortality in Postoperative Patients after Admission to the Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 39.

- Carriere, I.; Dupuy, A.M.; Lacroux, A.; Cristol, J.P.; Delcourt, C. Pathologies Oculaires Liees a l’Age Study Group. Biomarkers of inflammation and malnutrition associated with early death in healthy elderly people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 840–846.

- Dominguez de Villota, E.; Mosquera, J.M.; Rubio, J.J.; Galdos, P.; Diez Balda, V.; de la Serna, J.L.; Tomas, M.I. Association of a low serum albumin with infection and increased mortality in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1980, 7, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Ahn, J.Y.; Song, J.E.; Choi, H.; Ann, H.W.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Jeon, Y.D.; Kim, S.B.; Jeong, S.J.; et al. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock treated with early goal-directed therapy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzani, O.T.; Zampieri, F.G.; Forte, D.N.; Azevedo, L.C.; Park, M. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts 90-day mortality of septic patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, W.; Dong, Y.; Li, L. C-Reactive Protein-to-Albumin Ratio Predicts Sepsis and Prognosis in Patients with Severe Burn Injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 6621101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R.B.; Oktafia, P.; Saputra, P.B.T.; Purwati, D.D.; Saputra, M.E.; Maghfirah, I.; Faizah, N.N.; Oktaviono, Y.H. Alkaff, F.F. The roles of C-reactive protein-albumin ratio as a novel prognostic biomarker in heart failure patients: A systematic review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024, 49(5), 102475.

- Iwata, M.; Kuzuya, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Iguchi, A. Prognostic value of serum albumin combined with serum C-reactive protein levels in older hospitalized patients: continuing importance of serum albumin. Aging Clin Exp Res 2006, 18, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L. M.; et al. Predicting the outcome of artificial nutrition by clinical and functional indices. Nutrition 2009, 25, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.K.; Song, I-A.; Lee, J.H. Clinical usefulness of C-reactive protein to albumin ratio in predicting 30-day mortality in critically ill patients: A retrospective analysis. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 14977.

- Llop-Talaveron, J.; Badia-Tahull, M.B.; Leiva-Badosa, E. An inflammation-based prognostic score, the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts the morbidity and mortality of patients on parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2018, 37(5), 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, G.; Bertocchi, L.; Dal Bo, E.; Di Pasquale, C.L.; Zanetti, M. Identifying reliable predictors of protein-energy malnutrition in hospitalized frail older adults: A prospective longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018, 82, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rosa, M.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Giuliani, A.; Carella, M.; Magro, D.; Biscetti, L.; et al. Inflammation scores based on C-reactive protein and albumin predict mortality in hospitalized older patients independent of the admission diagnosis. Immun Ageing. 2024, 21(1), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baune, B.T.; Rothermundt, M.; Ladwig, K.H.; Meisinger, C.; Berger, K. Systemic inflammation (Interleukin 6) predicts all-cause mortality in men: results from a 9-year follow-up of the MEMO Study. Age (Dordr). 2011, 33(2), 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, E.; Grippo, F.; Frova, L.; Pantosti, A.; Pezzotti, P.; Fedeli, U. The increase of sepsis-related mortality in Italy: a nationwide study, 2003-2015. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019 Sep;38(9):1701-1708.

- National Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://esploradati.istat.it/databrowser/#/it/dw/categories/IT1,Z0810HEA,1.0/HEA_DEATH/DCIS_CMORTEM (accessed on 6 May 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).