Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

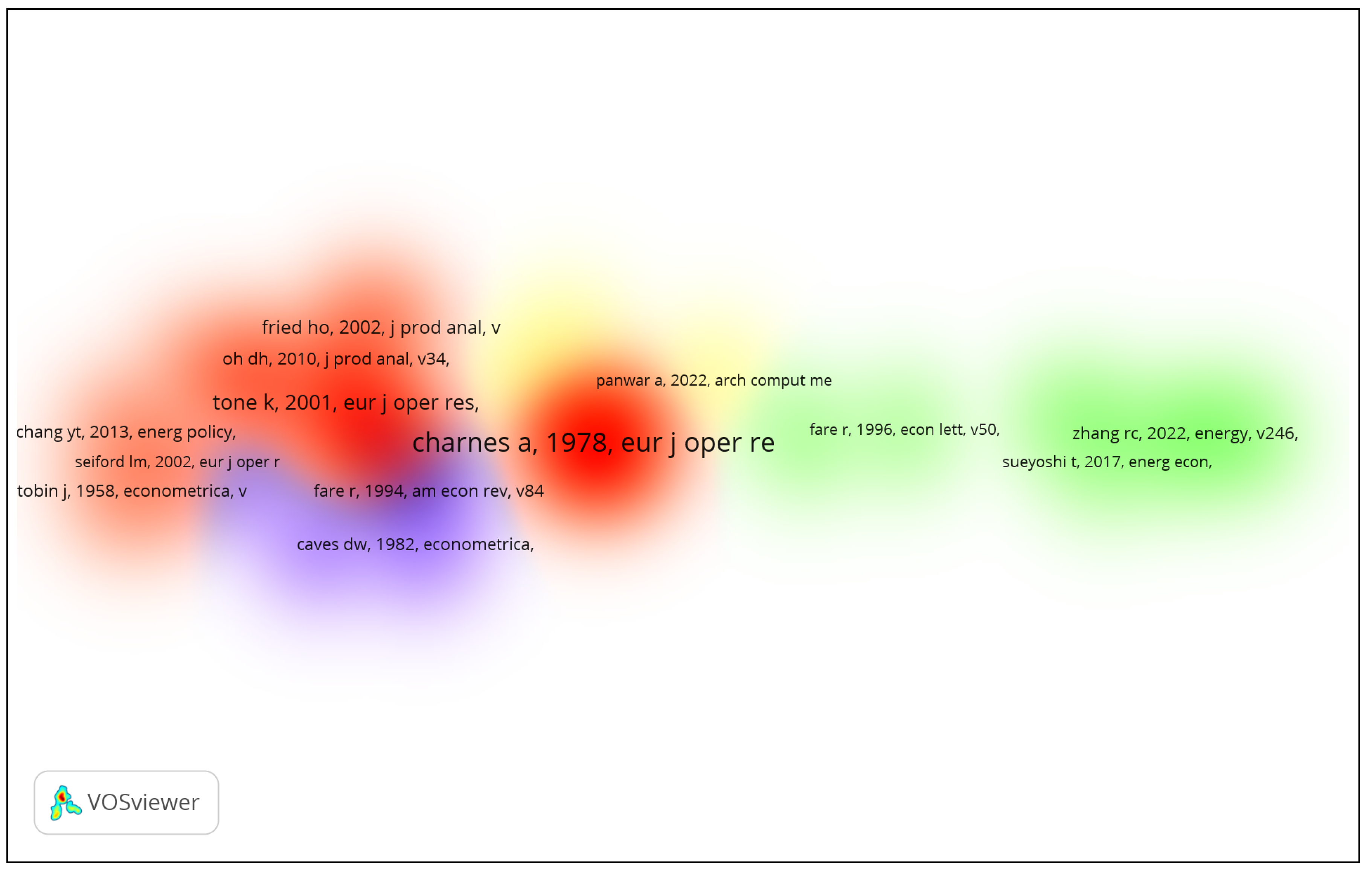

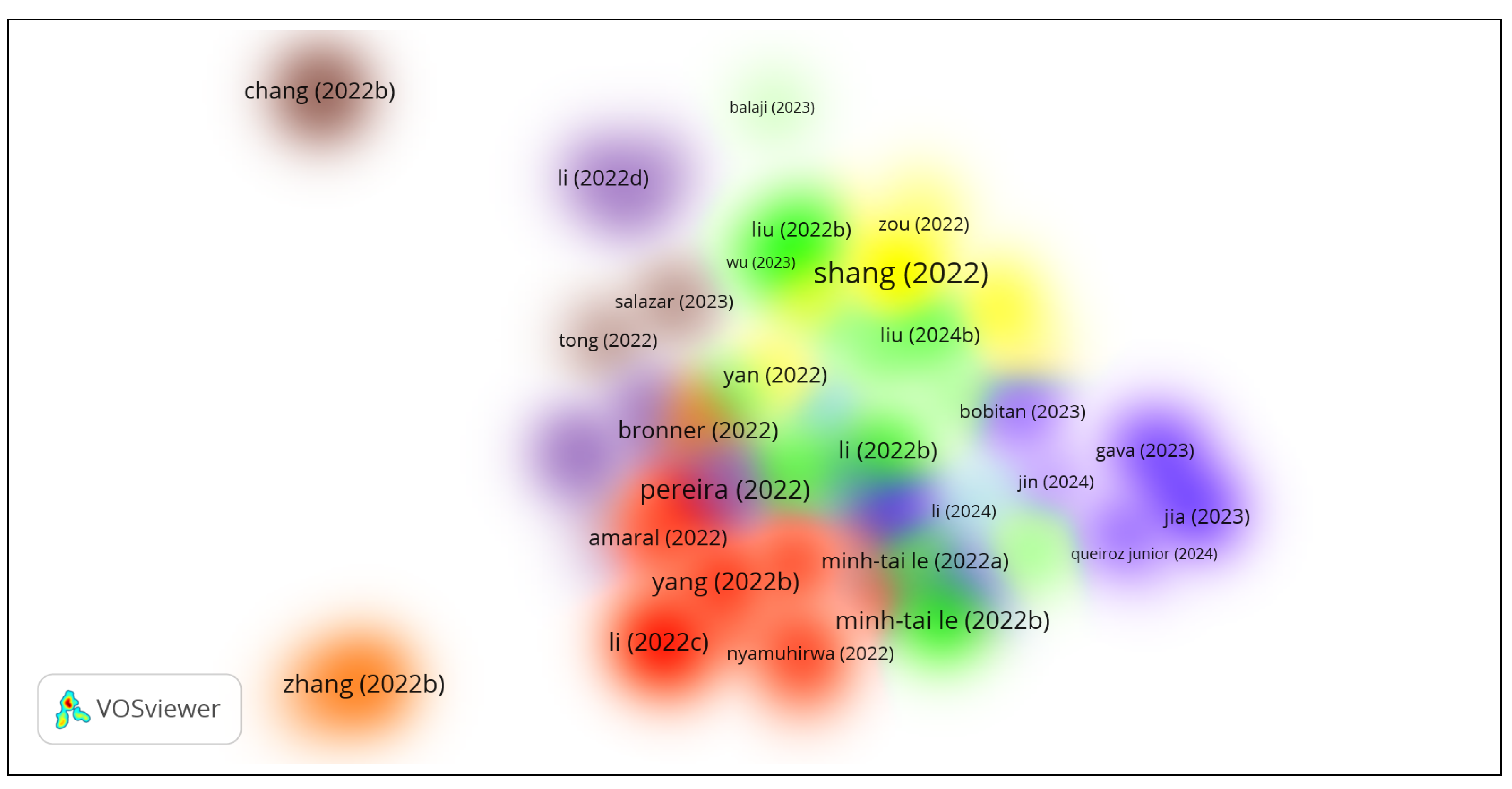

2. Related Works

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Selection

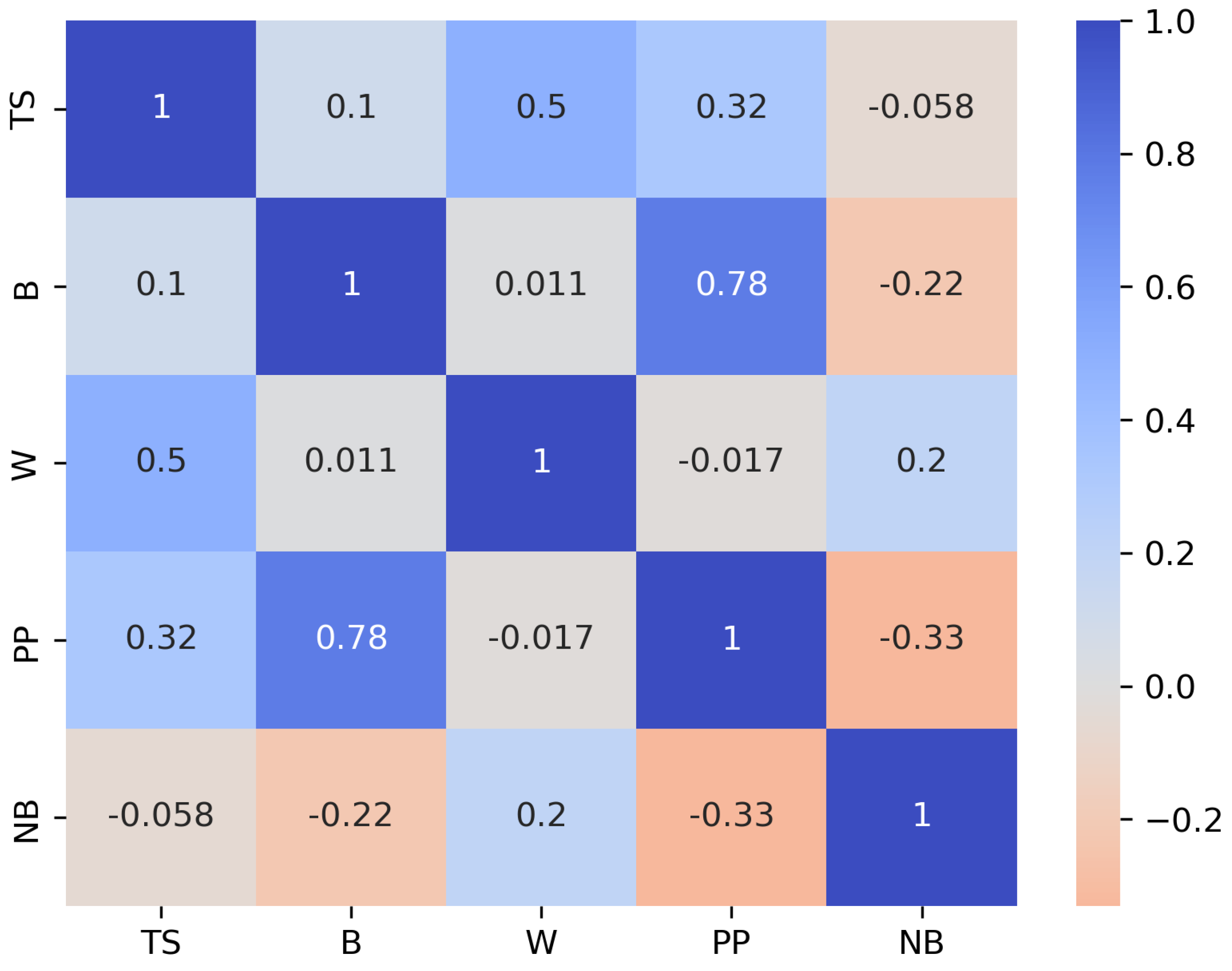

3.2. Variables Selection

3.3. Data Gathering

3.4. Outlier Detection

3.5. Return to Scale

3.6. Model Orientation

3.7. Bootstrap

4. Results

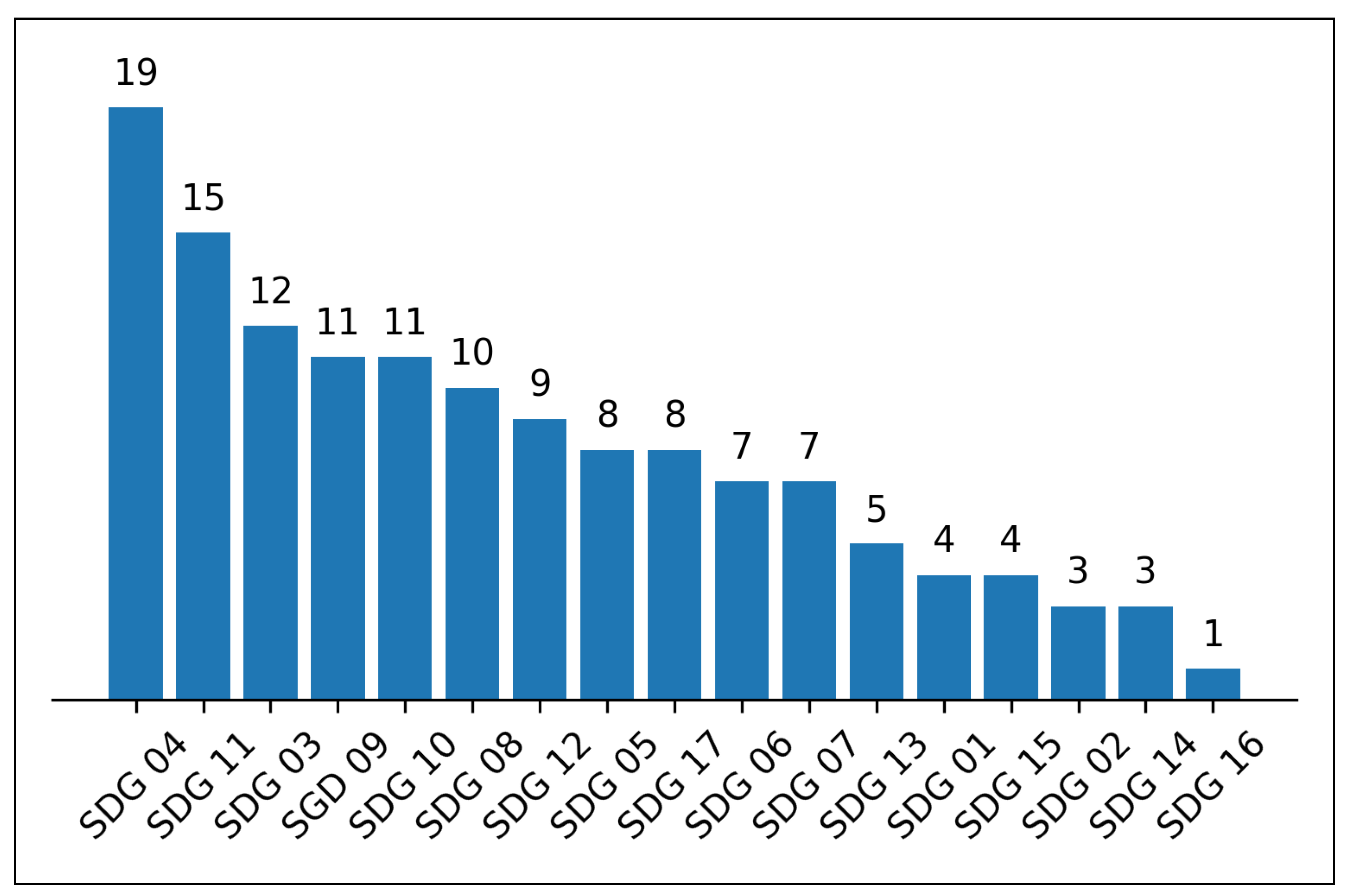

4.1. Projects Profile

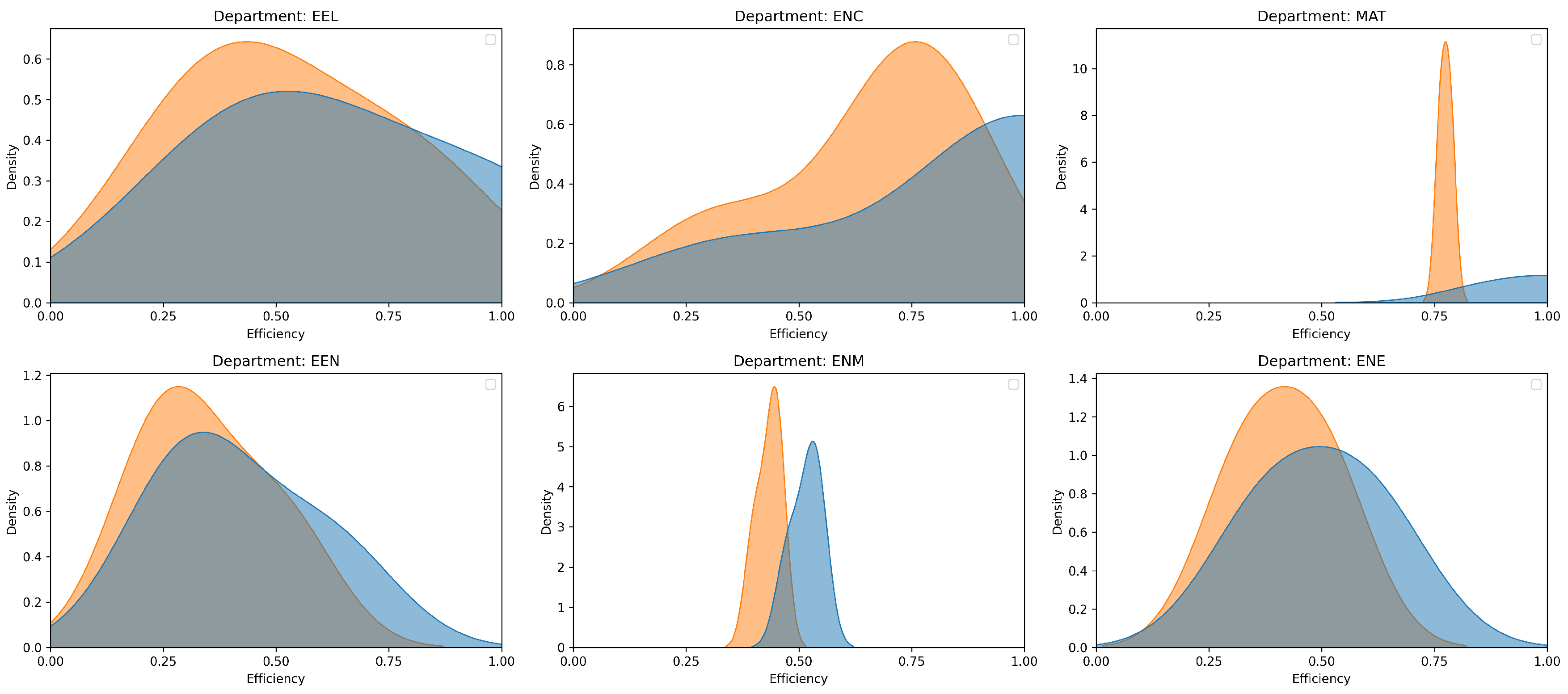

4.2. Bootstrap DEA Application

5. Discussions

6. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DMU | TS | B | W | PP | NB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMU 1 | 37 | $ 8,330.00 | 2430 | 1 | 50 |

| DMU 2 | 19 | $ 0.00 | 1140 | 0 | 1000 |

| DMU 3 | 9 | $ 4,080.00 | 1292 | 1 | 183 |

| DMU 4 | 13 | $ 850.00 | 875 | 2 | 62 |

| DMU 5 | 22 | $ 8,500.00 | 3396 | 2 | 161 |

| DMU 6 | 9 | $ 680.00 | 1658 | 0 | 750 |

| DMU 7 | 8 | $ 510.00 | 1000 | 0 | 255 |

| DMU 8 | 4 | $ 1,360.00 | 360 | 0 | 50 |

| DMU 9 | 29 | $ 73.10 | 3400 | 0 | 400 |

| DMU 10 | 16 | $ 170.00 | 480 | 0 | 260 |

| DMU 11 | 17 | $ 51.00 | 1522 | 0 | 50 |

| DMU 12 | 3 | $ 2,856.00 | 735 | 1 | 500 |

| DMU 13 | 15 | $ 22,666.67 | 1820 | 1 | 100 |

| DMU 14 | 6 | $ 0.00 | 1155 | 2 | 5 |

| DMU 15 | 5 | $ 68.00 | 555 | 0 | 57 |

| DMU 16 | 92 | $ 15,164.00 | 1952 | 4 | 59 |

| DMU 17 | 2 | $ 51,000.00 | 126 | 2 | 100 |

| DMU 18 | 42 | $ 13,804.00 | 5762 | 0 | 510 |

| DMU 19 | 24 | $ 68,000.00 | 1680 | 8 | 70 |

| DMU 20 | 20 | $ 0.00 | 1530 | 0 | 20 |

| Outlier 1 | 12 | $ 1,071.00 | 1360 | 0 | 30000 |

| Outlier 2 | 5 | $ 0.00 | 1095 | 1 | 8500 |

| Outlier 3 | 3 | $ 61,443.38 | 27 | 0 | 1500 |

Appendix B

| DMU | TS | B | W | PP | NB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMU 1 | 36 | $ 8,330.00 | 2430 | 1 | 50 |

| DMU 2 | 19 | $ 0.00 | 1140 | 0 | 1000 |

| DMU 3 | 9 | $ 4,080.00 | 1292 | 1 | 183 |

| DMU 4 | 13 | $ 850.00 | 875 | 2 | 62 |

| DMU 5 | 22 | $ 8,500.00 | 3217 | 2 | 161 |

| DMU 6 | 9 | $ 680.00 | 1658 | 0 | 750 |

| DMU 7 | 8 | $ 510.00 | 986 | 0 | 255 |

| DMU 8 | 4 | $ 1,360.00 | 360 | 0 | 50 |

| DMU 9 | 27 | $ 73.10 | 2662 | 0 | 400 |

| DMU 10 | 15 | $ 170.00 | 480 | 0 | 260 |

| DMU 11 | 17 | $ 51.00 | 1488 | 0 | 50 |

| DMU 12 | 3 | $ 2,856.00 | 735 | 1 | 500 |

| DMU 13 | 15 | $ 22,666.67 | 1815 | 1 | 100 |

| DMU 14 | 6 | $ 0.00 | 1155 | 2 | 5 |

| DMU 15 | 5 | $ 68.00 | 555 | 0 | 57 |

| DMU 16 | 42 | $ 15,164.00 | 1952 | 4 | 63 |

| DMU 17 | 2 | $ 51,000.00 | 126 | 2 | 100 |

| DMU 18 | 42 | $ 13,804.00 | 5079 | 0 | 510 |

| DMU 19 | 24 | $ 68,000.00 | 1680 | 8 | 70 |

| DMU 20 | 19 | $ 0.00 | 1496 | 0 | 20 |

References

- Ebi, K. L., Vanos, J., Baldwin, J. W., Bell, J. E., Hondula, D. M., Errett, N. A., ... & Berry, P. (2021). Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annual review of public health, 42(1), 293-315.

- Brundtland, G. H., & Khalid, M. (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford University Press.

- USAID (2024). Brazil Climate Change Country Profile: Climate. U.S. Agency for International Development. Retrieved January 5, 2025, from https://www.usaid.gov/climate/country-profiles/brazil.

- Grupo de Trabalho da Sociedade Civil para a Agenda 2030 (2024). VIII Relatório Luz da Sociedade Civil da Agenda 2030. Grupo de Trabalho da Sociedade Civil para a Agenda 2030 (GT Agenda 2030).

- Geissdoerfer, M., et al. (2017). The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm?. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757-768. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1-2), 62-77.

- Sachs, J. D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

- Curi Filho, W. R., and Wood, T. (2021). "Avaliação do Impacto das Universidades em Suas Comunidades." Cadernos EBAPE. BR, 19(3): 496–509. [CrossRef]

- QS (2024). QS World University Rankings: Sustainability 2024. Retrieved from https://www.topuniversities.com/sustainability-rankings?countries=br.

- Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429-444. [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. (2001). A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 130(3), 498-509. [CrossRef]

- Fried, H. O., Lovell, C. A. K., Schmidt, S. S., & Yaisawarng, S. (2002). Accounting for environmental effects and statistical noise in data envelopment analysis. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 17(1), 91-114. [CrossRef]

- Caves, D. W., Christensen, L. R., & Diewert, W. E. (1982). The economic theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output, and productivity. Econometrica, 50(6), 1393-1414. [CrossRef]

- Färe, R., Grosskopf, S., Norris, M., & Zhang, Z. (1994). Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries. The American economic review, 66-83.

- Zhang, R., Wei, Q., Li, A., & Chen, S. (2022). A new intermediate network data envelopment analysis model for evaluating China’s sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 356, 131845. [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T., & Goto, M. (2017). World trend in energy: an extension to DEA applied to energy and environment. Journal of Economic Structures, 6, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N., Olfati, M., Pant, P., & Snasel, V. (2022). Review of the evolution of data envelopment analysis: A bibliometric approach. Sustainability, 14(4), 2219.

- Tsaples, G., & Papathanasiou, J. (2021). Data envelopment analysis and the concept of sustainability: A review and analysis of the literature. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 138, 110664. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Song, M., & Zhao, X. (2022). The development of China’s Circular Economy: From the perspective of environmental regulation. Waste Management, 149, 186-198. [CrossRef]

- Xia, B., Dong, S., Li, Z., Zhao, M., Sun, D., Zhang, W., & Li, Y. (2022). Eco-efficiency and its drivers in tourism sectors with respect to carbon emissions from the supply chain: An integrated EEIO and DEA approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6951. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W., Zhang, L., Xu, J., Xie, Y., & Chen, H. (2022). Spatial–temporal evolution characteristics and influencing factors of industrial pollution control efficiency in China. Sustainability, 14(9), 5152. [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Wang, P., & Pal, R. (2022). Measuring sustainable technology R&D innovation in China: A unified approach using DEA-SBM and projection analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 209, 118393.

- Le, M. T., & Nhieu, N. L. (2022). An offshore wind–wave energy station location analysis by a novel behavioral dual-side spherical fuzzy approach: the case study of Vietnam. Applied Sciences, 12(10), 5201. [CrossRef]

- Qin, W., & Qi, X. (2022). Evaluation of green logistics efficiency in Northwest China. Sustainability, 14(11), 6848. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Yang, Y., Luo, G., Huang, J., & Wu, T. (2022). The economic recovery from traffic restriction policies during the COVID-19 through the perspective of regional differences and sustainable development: Based on human mobility data in China. Sustainability, 14(11), 6453. [CrossRef]

- Gava, O., Antón, A., Carmassi, G., Pardossi, A., Incrocci, L., & Bartolini, F. (2023). Reusing drainage water and substrate to improve the environmental and economic performance of Mediterranean greenhouse cropping. Journal of Cleaner Production, 413, 137510. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Huo, Y., & Yin, S. (2022). Sustainable financing efficiency and environmental value in China’s energy conservation and environmental protection industry under the double carbon target. Sustainability, 14(15), 9604. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., Yang, Y., Gong, G., & Gui, Q. (2022). The spatial network structure of tourism efficiency and its influencing factors in China: A social network analysis. Sustainability, 14(16), 9921. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Lu, X., Sun, Y., Yao, J., & Zhu, W. (2022). A Comprehensive Performance Evaluation of Chinese Energy Supply Chain under “Double-Carbon” Goals Based on AHP and Three-Stage DEA. Sustainability, 14(16), 10149. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M., Liu, J., Shi, H., & Guo, T. (2022). The effect of off-farm employment on agricultural production efficiency: micro evidence in China. Sustainability, 14(6), 3385. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, C., Cárdenas-Retamal, R., & Jaime, M. (2023). Environmental efficiency in the salmon industry—an exploratory analysis around the 2007 ISA virus outbreak and subsequent regulations in Chile. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(8), 8107-8135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Razzaq, A., Qin, J., Feng, Z., Ye, F., & Xiao, M. (2022). Does the expansion of farmers’ operation scale improve the efficiency of agricultural production in China? Implications for environmental sustainability. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 918060. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Wang, N., & Sun, G. (2022). Measurement of innovation-driven development performance of large-scale environmental protection enterprises investing in public–private partnership projects based on the hybrid method. Sustainability, 14(9), 5096. [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Park, S., An, S., Choi, W., & Lee, M. (2023). Research on Analyzing the Efficiency of R&D Projects for Climate Change Response Using DEA–Malmquist. Sustainability, 15(10), 8433. [CrossRef]

- Ebnerasoul, M., Ghannadpour, S. F., & Haeri, A. (2023). A collective efficacy-based approach for bi-objective sustainable project portfolio selection using interdependency network model between projects. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(12), 13981-14001. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zhang, R., & Li, A. (2024). A new concept of education-innovation-economy-environment sustainability system: a new framework of strategy-based network data envelopment analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1-45.

- Li, R., Luo, Y., Chen, B., Huang, H., & Liu, P. (2024). Efficiency of scientific and technological resource allocation in Chengdu–Chongqing–Mianyang Urban agglomeration: based on DEA–Malmquist index model. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(4), 10461-10483. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Han, G., Yang, H., & Li, X. (2024). A sustainable development study on innovation factor allocation efficiency and spatial correlation based on regions along the belt and road in China. Sustainability, 16(7), 2990. [CrossRef]

- You, M., Huang, Y., Wu, N., & Yuan, X. (2025). Efficiency Evaluation and Resource Optimization of Forestry Carbon Sequestration Projects: A Case Study of State-Owned Forest Farms in Fujian Province. Sustainability, 17(1), 375. [CrossRef]

- Callens, I., and Tyteca, D. (1999). "Towards Indicators of Sustainable Development for Firms: A Productive Efficiency Perspective." Ecological Economics, 28(1): 41–53.

- Zhou, H., Yang, Y., Chen, Y., & Zhu, J. (2018). Data envelopment analysis application in sustainability: The origins, development and future directions. European Journal of Operational Research, 264(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P., & Petersen, N. C. (1993). A procedure for ranking efficient units in data envelopment analysis. Management science, 39(10), 1261-1264. [CrossRef]

- Lovell, C. A. K., & Rouse, R. (2003). Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units using data envelopment analysis. Operations Research, 51(3), 493-503.

- Emrouznejad, A., & Cabanda, E. (2014). Super-efficiency in DEA: A review of the literature. International Journal of Applied Management Science, 6(3), 167-188.

- Simar, L., Wilson, P. W., & Paul, L. (2002). A general methodology for bootstrapping in data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 53(1), 23-29.

- Peña, J. M. (2008). Data Envelopment Analysis: A Methodology for Assessing the Efficiency of Decision-Making Units. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Serrano, A. L., Saiki, G. M., Rosano-Penã, C., Rodrigues, G. A. P., Albuquerque, R. D. O., & García Villalba, L. J. (2024). Bootstrap method of eco-efficiency in the Brazilian agricultural industry. Systems, 12(4), 136. [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. (1997). A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 130(3), 498-509. [CrossRef]

| Article | Overview |

|---|---|

| [22] | Use of a DEA-SBM-PA model to evaluate Green Technology R&D Efficiency in China (2011–2017). The results highlight efficiency disparities and identify improvement potentials for inefficient provinces. |

| [33] | Application of DEA with stochastic frontier analysis to assess innovation-driven performance in 20 environmental protection enterprises (2018–2020). The findings suggest optimizing resource use and labor-capital transformation for better efficiency. |

| [34] | Analyzis of 1,500 climate change R&D projects in Korea (2014–2020) using DEA. The results highlight inefficiencies in both technical and scale perspectives and propose improvement strategies to enhance national R&D efficiency. |

| [35] | Proposal of a sustainable model for project portfolio selection using DEA and Bayesian network modeling. The authors show the model outperforms traditional methods in a real case with 21 projects. |

| [36] | Introduction of a new sustainability system combining network DEA, K-means clustering, and Gini coefficient to evaluate university performance in promoting economic growth and environmental protection in China (2007–2019). The results show efficiency regress, with education-innovation gaining more priority over economy-environment. |

| [37] | Use of DEA-Malmquist analysis to evaluate technological resource allocation efficiency in the Chengdu-Chongqing-Mianyang region (2010–2019). The findings show an upward trend in efficiency, driven by technological progress and strong policy support. |

| [38] | Application of a super-efficient SBM-DEA-Malmquist model to evaluate innovation factor allocation along the Belt and Road in China (2012–2021). The results show strong agglomeration, with policy recommendations for enhancing regional innovation development. |

| [39] | Use of DEA to assess the operational efficiency of 14 state-owned forestry carbon sink projects in Fujian, identifying management capability and climate conditions as key efficiency factors. The findings suggest investment barriers limit small-scale forest farms from engaging in such projects. |

| Type | Variable | Abbreviation | Unit of Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Team Size | TS | People |

| Project Budget | B | USD | |

| Workload | W | Hours | |

| Output | Published Papers | PP | Papers |

| Number of Beneficiaries | NB | People |

| DMU | Depart | With Correction | 95% Confidence Level | Without Correction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||

| DMU 4 | EEL | 0.8131 | 0.7031 | 0.9723 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 7 | EEL | 0.4690 | 0.4064 | 0.5558 | 0.5669 |

| DMU 13 | EEL | 0.3076 | 0.2649 | 0.3672 | 0.3754 |

| DMU 6 | ENC | 0.8030 | 0.6689 | 0.9754 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 17 | ENC | 0.7457 | 0.6211 | 0.9861 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 2 | ENC | 0.7429 | 0.6266 | 0.9766 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 20 | ENC | 0.3184 | 0.2751 | 0.3616 | 0.3668 |

| DMU 14 | MAT | 0.7846 | 0.6709 | 0.9772 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 12 | MAT | 0.7637 | 0.6576 | 0.9803 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 3 | EEN | 0.5136 | 0.4468 | 0.6053 | 0.6211 |

| DMU 1 | EEN | 0.2962 | 0.2548 | 0.3424 | 0.3514 |

| DMU 18 | EEN | 0.2310 | 0.1933 | 0.2738 | 0.2794 |

| DMU 5 | ENM | 0.4466 | 0.3804 | 0.5287 | 0.5393 |

| DMU 8 | ENM | 0.4503 | 0.3919 | 0.5194 | 0.5297 |

| DMU 15 | ENM | 0.4020 | 0.3531 | 0.4687 | 0.4768 |

| DMU 9 | ENE | 0.5031 | 0.4266 | 0.5923 | 0.6065 |

| DMU 11 | ENE | 0.3315 | 0.2893 | 0.3771 | 0.3836 |

| DMU 19 | DSC | 0.7567 | 0.6339 | 0.9666 | 1.0000 |

| DMU 16 | EPR | 0.7190 | 0.6260 | 0.8339 | 0.8597 |

| DMU 10 | EAU | 0.5739 | 0.4902 | 0.6841 | 0.6974 |

| DMU | TS | B | W | PP | NB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMU 1 | 2.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 2 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 3 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 4 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 5 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 6 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 7 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 8 | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 9 | 8.1% | 0.0% | 21.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 10 | 9.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 11 | 2.7% | 0.0% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 12 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 13 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 14 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 15 | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 16 | 53.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.5% |

| DMU 17 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 18 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 11.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 19 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| DMU 20 | 4.0% | 0.0% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).