1. Introduction

In Ghana, agriculture is the backbone of the economy, supporting about 60% of the population, particularly in rural areas where smallholder farmers (SHFs) play a vital role in producing both food and cash crops [

1,

2]. SHFs are integral to the nation’s agricultural output and food security, contributing significantly to rural livelihoods and economic stability [

3]. Sustainable agricultural development is essential for reducing poverty and ensuring food security, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), which seeks to end hunger, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture [

4,

5].

Recognizing this, the United Nations (UN) and international development organizations have identified microfinance as a pivotal tool for poverty reduction (SDG 1: No Poverty) and economic empowerment (SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth) [

6,

7]. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are critical in enhancing financial inclusion, particularly for low-income populations and SHFs, who often lack access to formal banking services [

8,

9]. The ability of SHFs to invest in productive assets, manage risks, and expand agricultural activities depends on their access to affordable financial services, reinforcing the importance of financial inclusion as a driver of economic resilience and food security [

10,

11].

The Financial Inclusion Theory (FIT) underscores the importance of accessible financial services in reducing poverty, fostering economic growth, and enabling all individuals to participate fully in economic activities [

10,

12]. In line with this, the Government of Ghana has long recognized microfinance as a key strategy for promoting financial inclusion and supporting sustainable agriculture (SDG 2) and poverty reduction (SDG 1). This commitment was formalized through policies such as the Ghana Microfinance Policy (GHAMP) [

13] and the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy II [

14]. In 2011, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) brought MFIs under its regulatory supervision to enhance financial inclusion for low-income and rural communities, a move that aligned with global efforts to increase access to loans and promote inclusive economic growth (SDG 8). This was supported by legislative frameworks such as the Non-Banking Act of 2008 (Act 774) and the now-repealed Banking Act of 2004 (Act 673), which facilitated the licensing of approximately 484 MFIs by 2015 [

15].

The massive closure of MFIs poses a significant threat to financial inclusion and SHF productivity in Ghana, potentially hindering progress towards SDG 2 (Zero Hunger). Without access to loans, insurance, and business development services (BDS), SHFs face significant constraints in sustaining agricultural productivity and this may affect the overall rural economy in Ghana. Given the crucial role that MFIs play in supporting SHFs, it is essential to understand how their closure affects SHF productivity and the overall local economy in Ghana, as numerous studies on the financial sector crisis have focused on its impact on corporate businesses and the causes and corrective measures to address the crisis in different subsectors. Therefore, it is both urgent and necessary to investigate the impact of the closure of over 300 MFIs on the productivity of their dependent SHFs in Ghana, as understanding this impact is critical for developing policies and interventions that can support the affected SHFs and ensure sustainable agricultural practices, productivity and food security in the wake of the financial sector reform (FSR). Hence, the study seeks to address the research question: Does the closure of MFIs in Ghana affect the productivity of SHFs?

1.1 Closure of Microfinance Institutions

Despite government’s commitments to formalize the microfinance sector, the rapid expansion of MFIs led to significant regulatory challenges, including non-compliance, mismanagement, and the emergence of fraudulent operators [

16]. This situation mirrors Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan theory, which argues that institutional oversight is necessary to ensure order and stability. By 2014, the BoG had to intervene, shutting down approximately 50 MFIs due to operational unsustainability, which created uncertainty and financial distress among rural populations who rely heavily on MFIs’ services. The 2017 - 2019 FSR intensified these challenges, leading to the closure of 420 financial institutions, including 347 MFIs [

17].

MFIs play a crucial role in promoting financial inclusion (SDG 8), enhancing food security (SDG 2), and reducing poverty (SDG 1) by providing SHFs and other low-income groups with access to credit, savings, insurance, payment and transfer services and BDS. These financial and non-financial services help strengthen economic resilience and mitigate vulnerability to agricultural shocks [

12,

18,

19]. The Financial Inclusion Theory (FIT) highlights the importance of accessible financial services in fostering economic participation and productivity [

10,

12]. However, in contexts where financial access is already constrained, disruptions to MFI operations can have severe consequences on SHF productivity and economic growth. Despite the critical role of MFIs in serving underserved populations, regulatory actions such as widespread closures, if not carefully managed, risk excluding vulnerable groups from essential financial and non-financial services. In Ghana, for instance, the BoG did not implement adequate safeguards to protect SHFs and other low-income individuals who rely on MFIs before initiating their closure, raising concerns about the broader implications of such regulatory decision.

Moreover, the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) helps to contextualize the livelihood disruptions that SHFs may face due to the loss of MFI services. According to the SLF, households depend on five types of livelihood assets: financial, human, social, physical, and natural capital [

20,

21]. MFIs were central to SHFs' financial and human capital, offering loans, savings, insurance, and BDS that supported agricultural investments, risks mitigation and prudent farm management [

8,

22]. The closure of over 300 MFIs in Ghana directly undermined these financial and non-financial services, leaving SHFs vulnerable to external shocks and reducing their capacity to sustain agricultural productivity. Furthermore, the loss of social capital - trust-based networks formed through MFIs’ group lending mechanisms - exacerbated financial exclusion and economic instability [

23].

Notwithstanding these challenges, microfinance remains a crucial component of financial (loan, insurance) and non-financial (business development services [BDS], financial literacy and agricultural extension technology programs) services [

8,

24], for rural populations. Ledgerwood [

8], emphasizes that MFIs are designed to effectively respond to client needs, ensuring that financial products remain accessible, simple, and manageable. Access to loan is essential for enhancing agricultural productivity, increasing food production (SDG 2), and supporting rural livelihoods [

22]. From the SLF perspective, financial access strengthens SHFs' ability to accumulate assets, diversify income sources, and enhance resilience against agricultural shocks [

21,

25]. Well-structured financial services are fundamental to the development of the agricultural sector [

26].

In Ghana, where SHFs depend on microfinance services such as loans to purchase agricultural inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds, machinery), insurance to mitigate extreme weather conditions and market risks, and BDS (agricultural extension technology and financial literacy trainings) to manage farms, the closure of MFIs raises serious concerns about the long-term sustainability of rural livelihoods, agricultural productivity, and national food security [

4].

Agricultural productivity, defined by the FAO, is the ratio of agricultural outputs (such as crops, livestock, etc.) to inputs (such as land, labor, water, fertilizers, etc.) used in production [

27]. In this context productivity is measured in terms of yield per land area, where yield refers to the amount of agricultural product, that is, crops produced per unit of land area, typically expressed in tons per hectare (t/ha). Despite the closure of MFIs, it is possible for SHFs to maintain or even improve their productivity by leveraging the human capital (skills, knowledge, experiences) [

21,

23,

24], and social capital (social networks) [

8,

20,

28], developed through previous interactions with MFIs. The adaptability of SHFs in the face of formal financial and non-financial services disruptions (the results of MFI closures) highlights their resilience and capacity to utilize alternative resources to sustain agricultural productivity.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilized a Social Survey Research Design, incorporating both purposive and probability sampling techniques [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The choice of this design aligns with both SLF and FIT as they assess how disruptions in financial, human, and social capital (such as MFI closures) affect the overall livelihood assets of SHFs [

20,

21] and how the loss of MFIs impacts SHFs’ access to essential financial services [

10,

12].

The target population consisted of SHFs in Ghana, distributed across the three main agroecological zones: Northern, Middle Belt, and Southern Zones. To ensure a representative selection of SHFs affected by MFI closures, one region from each zone was randomly selected for data collection. The SLF-guided approach to sampling considered the livelihood vulnerabilities and financial dependency of SHFs, ensuring that the study captured both financial and non-financial livelihood impacts. Apart from purposively sampling the only active MFI in the Northern region, the sampling strategy involved systematic and random sampling of MFIs in the selected regions - Northern, Ashanti, and Western - to ensure inclusion of diverse financial and non-financial access experiences among SHFs.

The sampling process involved selecting 30% of active and closed MFIs in each of the selected region, with SHF clients forming the sampling frame. A total of 600 respondents were initially planned, split evenly between active and closed MFIs across the regions. However, after conducting fieldwork, one additional respondent from a closed MFI in the Western region was included, bringing the total to 601 respondents (301 from 11 closed MFIs and 300 from 11 active MFIs). The SLF approach ensured that the selection process reflected SHFs' access to MFIs’ services before (2018) and after (2020) the FSR, while FIT provided the theoretical lens to examine the financial exclusion impact resulting from MFI closures. Data were collected through interview schedules administered by the researcher and three assistants, with support from MFI staff.

2.1. Methods for Assessing the Financial and Livelihood Impact of Microfinance Closures on Smallholder Farmer Productivity

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (SPSSFW), version 20 was used to analyze the collected data. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to assess SHFs’ awareness of MFI closures and their alternative sources of support. Since SLF posits that financial access is a key determinant of livelihood sustainability, the study employed Independent Samples t-tests to evaluate differences in financial services (MFI services) utilization and crop yields before and after the MFI closures. This method is appropriate for comparing mean differences between independent groups, particularly, when assessing changes in financial access and agricultural productivity due to financial exclusion [

33].

To evaluate the impact of MFI closures on SHF productivity, the Standardized Mean Differences (SMDs) technique was employed. SMDs are widely used as effect sizes (ESs) to quantify the magnitude of differences between groups, making them relevant for assessing the financial exclusion effect measured through changes in crops yields [

33,

34]. The study applied Cohen’s d to estimate the magnitude of the impact of MFI closures on SHFs’ crops yields before and after the FSR [

35]. From an SLF perspective, the analysis of changes in crops yields serves as an indicator of how financial shocks impact SHFs' access to livelihood assets, particularly, financial (loans, insurance) and human capital (skills, knowledge, experiences). Similarly, FIT suggests that restricted financial access limits productivity, which justifies the use of effect size estimation to measure the extent of financial distress resulting from MFI closures [

10]. The adjusted effect size (ES) was calculated by subtracting the pre-ES from the post-ES, and the outcomes interpreted based on literature [

34,

36,

37,

38].

Confidence Intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the reliability of the estimated ESs, providing insight into the potential variability around observed impacts [

33,

34]. Given FIT’s emphasis on financial accessibility and economic stability, the inclusion of CIs adds statistical rigor to the findings, ensuring reliable estimates of financial exclusion’s effects on SHF productivity. Stata 18 software was used for computing ESs and CIs, facilitating a detailed analysis of the impact of MFI closures on SHFs before and after the FSR.

The data collection focused on SHFs' retrospective use of MFI services (loans, insurance, BDS), and yields of crops (rice, maize) before and after the 2019 BoG’s FSR that led to the mass closure of MFIs. This approach aligns with SLF’s emphasis on understanding how the livelihood assets influence SHFs’ agricultural productivity [

28] and FIT’s focus on measuring financial exclusion and its consequences on agricultural productivity.

2.2. Study Area

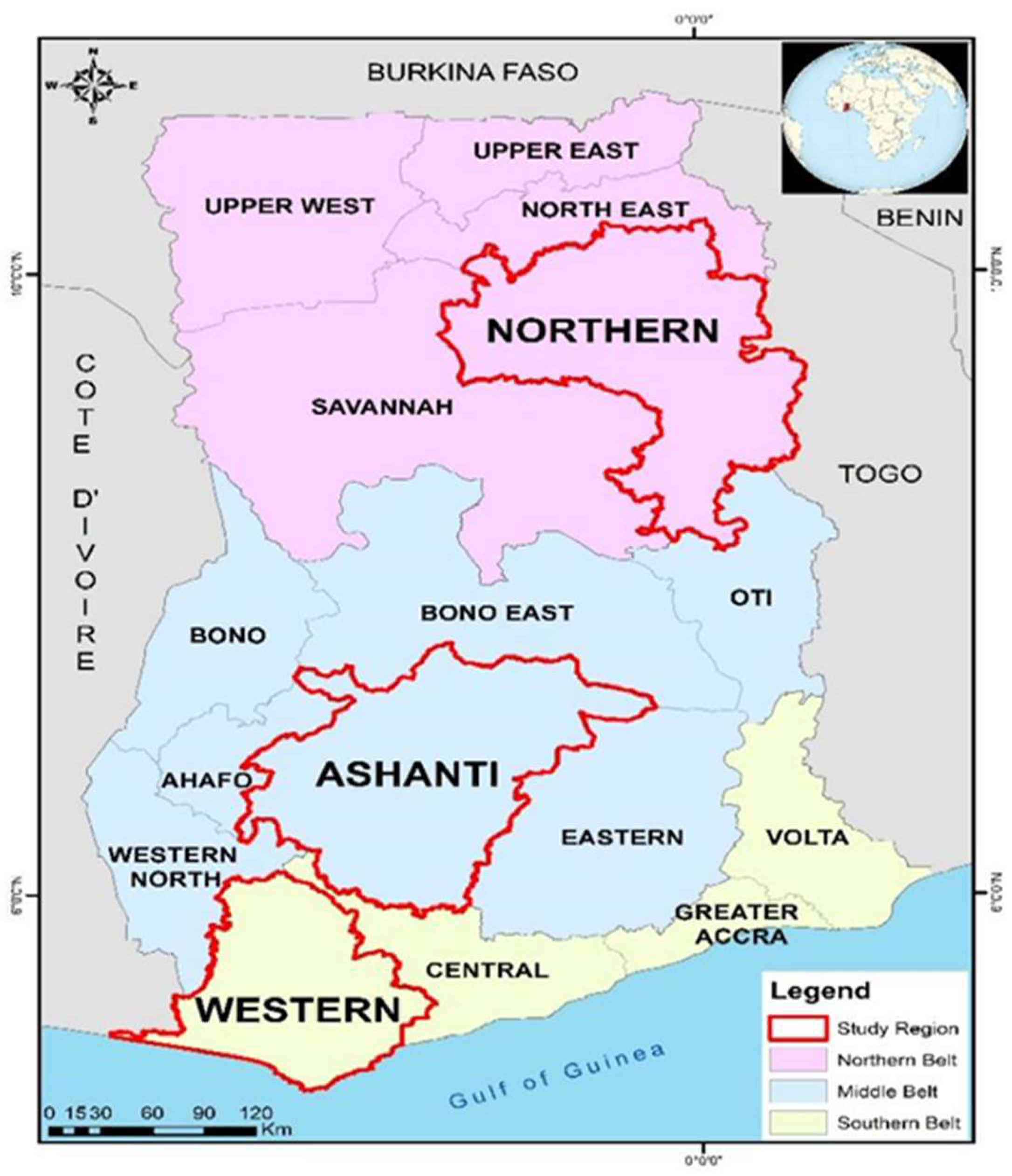

Ghana, located in West Africa, is broadly classified into three agroecological zones based on vegetation cover: the Northern Zone, Middle Belt, and Southern Zone, each with distinct climatic and agricultural conditions [

39] (

Figure 1).

These zones are also referred to as the Savannah Zone (Northern Belt), the Forest Zone (Middle Belt), and the Coastal Zone (Southern Belt) [

40]. Since SLF highlights the importance of the environment in shaping livelihood outcomes, these agroecological classifications are crucial for understanding the livelihood challenges SHFs face in different regions [

41].

Ghana is divided into sixteen political regions, grouped based on shared cultural, economic, and historical characteristics. The Northern Zone consists of five (5) regions, the Middle Belt comprises seven (7) regions, and the Southern Zone includes four (4) regions (

Figure 1). The study focused on the Northern, Ashanti, and Western regions, selected to represent Ghana’s agroecological diversity and financial inclusion levels. Since agriculture in Ghana is predominantly carried out by SHFs who are key clients of MFIs as suggested in literature [

8,

9,

12], it was essential to select study regions where MFI closures significantly affected rural financial access. The SLF framework justified this regional selection by emphasizing the livelihood vulnerabilities of SHFs, while FIT provided a theoretical basis for understanding how financial exclusion in these regions disrupts agricultural activities [

10,

12,

20,

21].

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the analysis and discussion of the study. The findings examined include SHFs' awareness of the massive closure of MFIs, alternative support sources available to SHFs for farming, utilization of MFI services (loans, insurance, and BDS), and the impact of MFI closures on SHFs' crops yields (rice and maize).

3.1. SHFs’ Awareness of MFI Closures: Financial and Livelihood Implications Within FIT and SLF Frameworks

The findings in

Table 1 reveal that 99.3% of SHFs were aware of the FSR that led to the closure of over 300 MFIs in 2019.

The high awareness level underscores the significance of MFIs in the livelihoods of SHFs and their integration into Ghana’s rural financial system. From an SLF perspective, this finding suggests that financial capital, which is central to rural livelihoods, was a well-recognized asset among SHFs [

20,

21]. The closure of MFIs meant a direct depletion of financial capital, which disrupted livelihood strategies and increased vulnerability among SHFs. Similarly, the widespread awareness of MFI closures demonstrates how deeply embedded these institutions were supporting SHFs, reinforcing FIT’s claim that inclusive financial systems are critical for economic stability [

18,

19].

3.2 Alternative Sources of Support and Their Implications for SHFs’ Livelihoods and Financial Inclusion

Table 2 reveals that 54.1% of SHFs relied on relatives for financial and material support, while 26.1% combined personal savings with family assistance. Only 13.3% depended solely on savings, and 6.5% used a revolving fund strategy between farm and non-farm activities.

The SLF framework suggests that when financial capital is disrupted, individuals rely on other livelihood assets - such as social capital (relatives [family] and community networks) and human capital (skills, knowledge [financial literacy], experiences,) to cope [

21,

25]. The findings support this claim, as SHFs turned to their social networks (relatives) and diversified financial strategies to mitigate the impact of MFI closures.

From an FIT perspective, this reliance on informal financial mechanisms highlights the risks of financial exclusion which can undermine progress towards achievement of economic stability (SDG 8). Without access to formal credit systems, SHFs may face higher borrowing costs, limited investment capacity, and reduced ability to expand agricultural activities [

11], which may jeopardize the attainment of food security (SDG 2). The fact that only a small percentage of SHFs depended solely on savings indicates the critical role MFIs played in providing financial services that informal networks alone could not fully replace.

3.3 SHFs’ Utilization of MFI Loans (Loan Investment in Farms): Implications for Financial Inclusion and Livelihoods

Table 3 shows a significant reduction (less than 1% significant level [SL]) in loan investments for SHFs of closed MFIs after the FSR. In 2018, there was no meaningful difference (-0.010) in loan investments in farms between SHFs of active and closed MFIs. However, by 2020, the mean difference widened to -0.650, indicating a severe reduction in loan access for SHFs of closed MFIs, a threat to economic stability (SDG 8).

FIT explains this outcome as a classic consequence of financial exclusion - when MFIs are closed, credit-dependent SHFs struggle to secure loans from alternative sources, leading to lower investment in farming [

18], which may jeopardize sustainable agriculture (SDG 2).

From an SLF standpoint, this decline in loan access indicates a depletion of financial capital, which, in turn, weakens other livelihood assets. Without access to loans, SHFs face difficulty investing in agricultural inputs (physical capital - fertilizers, pesticides, improved seeds, farm tools), hiring labor (human capital), or expanding farming operations [

28]. This further increases vulnerability and forces SHFs to seek informal and sometimes costlier financial sources for agricultural investments, affecting profitable and sustainable agriculture (SDGs 8 and 2).

3.4 SHFs’ Use of Insurance Services for Risk Management: Implications for Financial Inclusion and Livelihoods

Table 4 reveals that in 2018, both groups of SHFs had almost similar access to MFI insurance services (-0.04189 difference). However, by 2020, the utilization gap widened significantly (-0.94305), less than 1% SL, indicating that SHFs from closed MFIs lost access to insurance services almost entirely, a situation which may be very detrimental to sustainable agriculture (SDG 2).

This finding aligns with FIT’s assertion that financial exclusion increases vulnerability to economic shocks [

10,

12]. Without insurance cover, SHFs are more exposed to risks such as crop failure due to extreme weather conditions, illness, or loss of assets, making it difficult to recover from financial setbacks.

From an SLF perspective, insurance is a critical form of financial capital that helps SHFs build resilience against unexpected shocks [

20]. The loss of MFI-provided insurance further weakened SHFs’ financial security, leaving them more susceptible to livelihood disruptions. This can affect SHFs’ farm activities and economic growth (SDG 8).

3.5 SHFs’ Use of BDS for Agricultural Growth and Food Security (SDG 2): Implications for FIT and SLF

The results in

Table 5 indicate that before the FSR, both SHF groups had nearly equal access to BDS (-0.03298 difference). However, by 2020, the gap widened significantly (-0.98997 difference), less than 1% SL, with SHFs of closed MFIs losing nearly all access to BDS.

From an SLF standpoint, the loss of BDS means a reduction in the provision of agricultural extension technology and literacy training programs or services which equip SHFs with financial management knowledge, skills and experiences (human capital) and business networks (social capital), which are essential for improving productivity and market access [

25]. This reduction may affect sustainable agriculture (SDG 2).

FIT also emphasizes that financial services go beyond credit and savings - MFIs play a broader role in providing financial literacy training, and advisory services [

8,

12]. The absence of these services deprived SHFs of essential financial management principles and modern agricultural technical know-how, hindering their ability to maximize productivity and manage their farms effectively post-closure, a threat to agricultural sustainability (SDG 2).

3.6 Impact of MFI Closures on SHFs’ Crop Yields: Implications for SDG 2 (Food Security), SDG 8 (Economic Growth), SLF, and FIT

3.6.1 Impact of MFI Closures on Rice Yields: Implications for Agricultural Productivity, SDG 2 (Food Security), SLF, and FIT

Table 6 presents the mean differences in rice yields before (-0.16544 t/ha) and after (-0.21828 t/ha) the FSR for SHFs affected by MFI closures. These differences were found to be statistically insignificant, indicating that there was no substantial change in rice productivity following the MFI closures. This suggests that while the loss of microfinance services may have posed financial challenges, it did not necessarily result in an immediate and significant decline in rice output.

From an SLF perspective, this outcome may be attributed to SHFs’ ability to leverage social capital (family and community support networks) and human capital (knowledge, skills, and farming experience) gained from previous engagements with MFIs [

21]. These factors likely contributed to stability in rice productivity despite the absence of formal financial and non-financial services.

Furthermore, FIT posits that financial exclusion does not always lead to productivity declines, as farmers may adopt alternative financial strategies to sustain operations [

12,

28]. Some SHFs might have mitigated the impact of MFI closures by relying on personal savings, informal credit arrangements, or community-based financial support systems, allowing them to maintain investment levels in farm inputs.

While the results indicate no significant decline in rice yields post-closure, they highlight the adaptive capacity of SHFs in managing financial shocks. However, the long-term implications of sustained financial exclusion warrant further investigation, particularly in ensuring continuous agricultural growth and food security (SDG 2) while promoting decent work and economic resilience (SDG 8).

3.6.1.1 Effect Size Estimation of Rice Yields: Implications for Agricultural Productivity, SDG 2 (Food Security), SLF, and FIT

According to FIT, the closure of MFIs should have significantly disrupted SHFs' productivity by limiting access to credit in 2020 which will in turn affect crops yields. However, the effect size estimation suggests that financial intermediation, while important, did not appear to be the sole determinant of rice yields. The small effect sizes - approximately -0.2 t/ha (2018) and -0.3 t/ha (2020) - observed in

Table 7, according to Cohen’s principle [

35], indicate that SHFs of closed MFIs might have been less financially dependent on MFIs for rice farming.

The SLF provides an alternative explanation. for our findings. The estimation of the small effect size post-closure, suggests that SHFs likely leveraged support from relatives and trust-based networks (social capital) and knowledge, experiences, and skills (human capital) gained through past interactions with MFIs to maintain productivity [

20,

21]. These suggest that adaptive strategies help mitigate financial shocks in smallholder agriculture, thus supporting sustainable practices and food security (SDG 2).

3.6.1.2. Adjusted Effect Size of Rice Yields: Implications for Agricultural Productivity, SDG 2 (Food Security), SLF, and FIT

The adjusted effect size, approximately -0.08 t/ha, presented in

Table 8, further supports the argument that while MFI closures had some impact on rice yields for SHFs of the closed MFIs, the effect was minimal in practical terms.

From an FIT perspective, this suggests that the affected SHFs had alternative financial sources, whereas from an SLF viewpoint, this supports the idea that SHFs’ resilience strategies helped maintain productivity. This is a possibility that can be harnessed for sustainable agricultural productivity (SDG 2).

3.6.2. Impact of MFI Closures on Maize Yields: Implications for Agricultural Productivity, SDG 2 (Food Security), SLF, and FIT

Table 9 presents the mean differences in maize yields before (0.03644 t/ha) and after (0.04504 t/ha) the FSR. These differences were found to be positive and statistically insignificant, indicating that there was no substantial change in maize yields of the affected SHFs relative to their counterparts in the active group following the MFI closures. This suggests that, despite the loss of formal financial and non-financial services, the SHFs of the closed group did not experience a significant decline in maize yields.

From an SLF perspective, the resilience of SHFs can be attributed to their adaptive capacity and diversification of financial sources [

25]. Farmers might have compensated for financial constraints by leveraging alternative livelihood strategies, such as, accessing community-based and family support networks (social capital), or adopting modern but low-cost farming inputs (physical capital), and agricultural technical skills, financial management knowledge, and practical farming experiences (human capital) acquired through prior MFIs’ extension training and literacy programs (BDS) to maintain production levels [

8,

20,

21].

Similarly, FIT suggests that when access to formal credit is disrupted, SHFs may turn to informal financing mechanisms such as family support, community savings groups, or trust-based credit arrangements [

10,

12]. These alternative financial channels might have helped sustain investment in agricultural inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds, pesticides, irrigation facilities, farming tools), thereby maintaining maize yields.

While the findings indicate that SHFs were able to avoid immediate productivity losses, the long-term consequences of continued financial exclusion permit further investigation. Ensuring sustained agricultural growth and food security (SDG 2) requires strengthening resilient financing models that support smallholder farmers beyond short-term coping strategies.

3.6.2.1. Effect Size Estimation of Maize Yields: Implications for Agricultural Productivity, SDG 2 (Food Security), SLF, and FIT

FIT suggests that access to financial institutions, such as MFIs, is critical for economic productivity. However, the magnitude of the effect sizes - approximately 0.1 t/ha in 2018 and 2020 respectively - observed in

Table 10, per Cohen’s principle are small effect sizes [

35].

These suggest that maize yields were not heavily dependent on MFI financing. According to FIT, if financial intermediation was a primary factor in maize cultivation, the closure of MFIs should have resulted in a large negative ES post-closure, which did not occur. This indicates that the affected SHFs were either not solely dependent on MFIs for maize production or relied on alternative sources of financial support [

10,

28].

The SLF provides further explanation for these small effect sizes. Rather than being entirely dependent on financial capital (loans), the affected SHFs appeared to rely on social (relatives, community networks) and human capital (skills, knowledge, experiences) [

8,

21,

28], as well as other adaptive strategies, to maintain maize productivity (SDG 2). These highlight the importance of resilience mechanisms in agricultural communities.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Key Findings and Their Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study align with the FIT and the SLF in explaining the effects of MFI closures on SHFs. From an FIT perspective, financial exclusion due to MFI closures restricted SHFs' access to essential financial and non-financial services, limiting their ability to invest in farm activities and reinforcing poverty cycles. From an SLF standpoint, SHFs adapted by leveraging alternative livelihood assets, including human, social, and physical capital.

With this and all the remaining results and discussions, the key findings and their theoretical implications are summarized as follows:

Loan Services and Financial Exclusion: Before the FSR, there was no significant difference in loan investments between SHFs from closed and active MFIs. However, post-FSR, SHFs from closed MFIs faced a sharp decline in loan access, leading to reduced investments in farm activities. FIT explains that financial exclusion restricts investment opportunities, reinforcing economic vulnerability and limiting progress toward SDG 1 (poverty reduction).

Insurance Services and Agricultural Risk Management: Insurance usage was comparable across the two groups of SHFs before the FSR, but post-FSR, SHFs from closed MFIs lost access to formal insurance, increasing their exposure to agricultural risks. This loss undermined sustainable agriculture and economic stability (SDGs 2 and 8). SLF highlights how the reduction in financial capital forced SHFs to rely on informal safety nets, which are often inadequate for long-term resilience.

BDS Utilization and Productivity: The FSR significantly affected access to business development services (BDS), such as agricultural extension technology and financial literacy trainings, which are essential for productivity. FIT suggests that financial exclusion disrupts access to such non-financial services, which are critical for productivity and economic stability. This disruption undermined efforts toward SDGs 2 and 8, as SHFs lost opportunities to enhance farm efficiency and market competitiveness.

Rice and Maize Yields and SHFs’ Adaptation: Despite financial disruptions, no significant differences in rice and maize yields were observed before or after the FSR. The estimated effect sizes further indicate that while MFI closures had a notable impact, SHFs demonstrated resilience by leveraging alternative resources to sustain agricultural productivity (SDG 2). SLF explains this adaptation through the use of resilience mechanisms such as human capital, financial strategies, social networks, innovations, informal finance, and family support.

This study found that, following the FSR, the affected SHFs faced immediate financial and non-financial services disruption due to MFI closures but demonstrated remarkable resilience. Leveraging prior MFI engagements, informal financial networks, community-based resources, and family support, the affected farmers sustained productivity. These resilience mechanisms underscore the critical role of informal and alternative financial mechanisms in rural livelihoods, suggesting a need for policy, financial inclusion and rural agricultural development interventions that strengthen these informal systems and integrate them with formal financial infrastructures to ensure sustainable smallholder agriculture and rural economic development aligned with global goals such as SDG 2 (food security), SDG 1 (poverty alleviation) and SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth).

4.2. Policy Implications and Recommendations: A Financial Inclusion and Livelihoods Perspective

The findings underscore the importance of financial inclusion in supporting SHFs' productivity and economic stability (FIT’s perspective). While alternative coping mechanisms (SLF’s perspective) have helped in the short term, long-term solutions are needed to ensure financial sustainability and agricultural productivity. The following recommendations are proposed:

Enhancing Alternative Loan Services: Given the decline in loan access post-FSR, expanding mobile-based microloans, rural credit schemes, and community lending models is essential. FIT emphasizes that inclusive financial systems are necessary for sustained economic growth (SDG 8).

Expanding Agricultural Insurance to enhance Financial Resilience (SLF Perspective): SLF highlights the importance of financial capital in mitigating livelihood risks. The loss of insurance access post-FSR left SHFs vulnerable to risks. Subsidized insurance or public-private partnerships should be introduced to provide affordable insurance coverage tailored to SHFs' needs, ensuring continued investment in agricultural productivity (SDG 2).

Strengthening BDS and Financial Literacy: BDS plays a crucial role in enhancing human capital, as emphasized by SLF, by equipping SHFs with knowledge and skills to optimize farm productivity. Alternative support channels should be developed through NGOs, agricultural extension services, digital platforms, and cooperatives to provide SHFs with ongoing training in agricultural technical know-how and farm management, financial literacy, as well as market access (SDGs 2 and 8).

Supporting SHFs’ Resilience and Productivity: SLF admits that a diversified livelihood strategy, including physical, human, social, financial and natural capital, enhances adaptability and economic security. The maintenance of stable rice and maize yields post-FSR suggests that SHFs adapted well, but sustaining this resilience requires investments in improved seeds, climate-resilient practices, and agricultural technology, reducing production risks, and increasing productivity (SDG 2). Strengthening market access is also crucial for ensuring economic stability (SDG 8).

Promoting Financial Resilience and Diversification: Encouraging income diversification, improved savings mechanisms, and climate-resilient farming practices can enhance SHFs’ long-term agricultural productivity, food security, decent work and economic growth (SDGs 2 and 8).

Addressing these gaps will not only enhance SHFs' rice and maize productivity and economic stability but also contribute to sustainable agricultural development, poverty reduction, and financial inclusion (SDGs 1, 2, and 8).

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study encountered several challenges, notably delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions, which significantly prolonged data collection, particularly in the Ashanti region. To mitigate financial constraints, we reviewed the budget and supplemented it with additional support from my wife, ensuring the successful completion of data collection.

Additionally, the research specifically examined the impact of MFI closures on SHFs agricultural productivity but did not include a comparative analysis between SHFs with and without prior MFI engagements. Future research should explore these differences to provide deeper insights into the financial inclusion gap left by MFI closures and its broader implications for agricultural resilience and rural livelihoods.

Author Contributions Statement

Conceptualization: Joseph Apor Adjei (J. A. A.), Investigation: J. A. A., Data curation: J. A.A. and Seth Dankyi Boateng (S. D. B.), Methodology: J.A.A. and S.D.B., Data Analysis: J.A.A., Research administration: J. A. A., S. D. B., and Keiichi ISHII (K. I.), Resources: J. A. A. and K. I., Supervision: S. D. B., and K. I., Writing - original draft: J. A. A., Writing - reviewing and editing it critically for intellectual content: J.A.A., K. I. and S.D.B., Validation: K. I. and S. D. B., All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this research.

Ethical Approval Statement

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Agricultural Economics, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University. The research adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring they were fully aware of the study's purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participation was entirely voluntary, with respondents having the freedom to withdraw at any time without any consequences.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is available upon request. Due to ethical concerns and participant confidentiality, access is restricted to authorized users.

Acknowledgments

I dedicate this manuscript to my wife, Linda Eshun, for her unwavering support and financial assistance during data collection challenges caused by COVID-19. Special thanks to my research assistants - Samuel Mensah, GodBless Adu-Gyamfi, and Godfred Amihere - for their valuable assistance in the field surveys. I am grateful to Dr. Colecraft Aidoo, Dr. Francis Seglah, Assistant Professor Estudius Francis Megazi, Frank Botchway, Frank Amofa-Agyemang, Mustapha Nyemewero, and Ebow Dublin for their diverse contributions. Special appreciation to Joseph Archer, my driver, whose dedication ensured safe travels throughout the study regions.

References

- Amfo, B.; Ali, E.B.; Ansah, I.G.K. Agricultural productivity and financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa: A panel data analysis. AFR 2021, 81, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Ohene-Ntow, I.D.; Asuming-Brempong, S. Agricultural credit allocation and constraints analyses of selected maize farmers in Ghana. JEMT 2013, 2, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akudugu, M.A.; Guo, E.; Dadzie, S.K. Adoption of modern agricultural production technologies by farm households in Ghana: What factors influence their decisions? JBAH 2012, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture: Leveraging Food Systems for Inclusive Rural Transformation 2017. FAO of the United Nations; Rome, Italy; 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/58fe36c1-b29a-45d7-b684-d3b3287f3f60/content (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019; UN DESA: New York, USA, 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP). Microfinance and Financial Inclusion: A Tool for Poverty Reduction. Policy Research Working Paper No. 55377; CGAP Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/CGAP-Access-to-Financial-Services-and-the-Financial-Inclusion-Agenda-around-the-World-Jan-2011.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Honohan, P. Finance for All? Policies and Pitfalls in Expanding Access (World Bank Policy Research Report). World Bank Publications; Washington, D.C., USA; 2008: 99-133. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/932501468136179348 (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Ledgerwood, J. Microfinance Handbook: An institutional and financial perspective. World Bank, Washington D. C., USA, 1999; 33-128.

- Asante-Addo, C.; Weible, D.; Zeller, M. Farmers' demand for financial services in Ghana: The case of maize farmers. AFR 2017, 77, 29–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. World Bank Publications; Washington, DC, USA, 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/29510.

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. 1st ed. Public Affairs; New York, NY, USA, 2011; 1333-182.

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Microfinance meets the market. JEP 2009, 23, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Microfinance Policy (GHAMP). Ghana Microfinance Policy Paper. FinDev Gateway 2006, 1-22. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/mfg-en-paper-ghana-microfinance-policy-nov-2006.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS) II. Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy. National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) 2006, 22-37. Available online: https://ndpc.gov.gh/media/Growth_and_Poverty_Reduction_Strategy_GPRS_II_2006-2009.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Bank of Ghana (BoG). Operating Rules and Guidelines for Microfinance Institutions. Bank of Ghana 2019. Available online: https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Operating-Rules-and-Guidelines-for-Microfinance-Institutions.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Gillespie, N.; Dietz, G. Trust repair after organization-level failure. AMR 2009, 34, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Ghana. Request for Expressions of Interest: Short-Term Consultant to Support Bank of Ghana Resolutions Office. Ministry of Finance, Ghana 2022. Available online: https://mofep.gov.gh/adverts/2022-09-27/request-for-expressions-of-interest-gh-mof-fsd-315018-cs-indv (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Expanding credit access: Using randomized supply decisions to estimate the impacts. RFS 2010, 23, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, A.; Kalmi, P.; Ruuskanen, O.P. Social capital and access to credit: Evidence from Uganda. The JDS 2016, 52, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Institute of Development Studies (IDS) Sustainable Livelihoods Research Program (SLP) Series 7, Working Paper 72, Brighton, UK; 1998. Available online: https://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/david.harvey/AEF806/Sconnes1998.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Department for International Development (DFID). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. DFID Publications; London, UK; 1999. Available online: https://www.livelihoodscentre.org/-/sustainable-livelihoods-guidance-sheets (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Zeller, M.; Schrieder, G.; von Braun, J.; Heidhues, F. Rural Finance for Food Security for the Poor: Implications for Research and Policy (Food Policy Review No. 4). International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); Washington, D.C., USA; 1997. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5056546_Rural_finance_for_food_security_for_the_poor (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Hitchins, R.; Elliott, D.; Gibson, A. Making business service markets work for the rural poor: A review of experience. EDM 2005, 16, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Savonitto, B.; Thuysbaert, B.; Udry, C. Impact of savings groups on the lives of the poor. PNAS 2017, 114, 3079–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, F. Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK; 2000; 10-199.

- Lin, J.Y.; Martin, W. The financial crisis and its impacts on global agriculture. AE 2010, 41, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). World agriculture: Towards 2030/2050. Prospects for food, nutrition, agriculture, and major commodity groups. FAO of the United Nations; Rome, Italy, 2006. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/em2009/docs/FAO_2006_.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science 2016, 354, 1288–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J., Jr. Survey research methods (Fifth Edition). SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA, 2014; 1-154.

- Sudman, S. Applied sampling. Academic Press, New York, New York 10003, USA, 1976; 1-222.

- Bailey, K.D. Methods of social research (Fourth Edition). Free Press, New York, N.Y. 10022, USA, 1994; 3-523.

- Kish, L. Survey sampling. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA, 1965; 1-59.

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics without maths for psychology: Using SPSS for Windows, (Third Edition). Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, England, 2004; 1-159, 206-289.

- Durlak, J.A. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. JPePsy 2009, 34, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Second Edition). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA, 1988.

- Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W. School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior: Update of a meta-analysis. AJPM 2007, 33, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.B.; Gottfredson, D.C.; Najaka, S.S. School-based prevention of problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. JQC 2001, 17, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacha-Haase, T.; Thompson, B. How to estimate and interpret various effect sizes. JCP 2004, 51, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessah, E.; Amponsah, W.; Ansah, S.O.; Afrifa, A.; Yahaya, B.; Wemegah, C.S.; Tanu, M.; Amekudzi, L.K.; Agyare, W.A. Climatic zoning of Ghana using selected meteorological variables for the period 1976-2018. MA 2022, 29, e2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessah, E.; Boakye, E.A.; Agodzo, S.K.; Nyadzi, E.; Larbi, I.; Awotwi, A. Increased seasonal rainfall in the twenty-first century over Ghana and its potential implications for agriculture productivity. EDS 2021, 23, 12342–12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darfour, B.; Rosentrater, K.A. Agriculture and food security in Ghana. In Proceedings of the 2016 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Orlando, USA, 17th to 20th July, 2016. (Paper No. 162460507, pp. 1–16). American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).