The analysis of the available data suggests that the effective implementation of a diverse set of financial tools can significantly contribute to enhancing the sustainability and growth of family farms. These results emphasize the need for tailored financial instruments that specifically address the unique challenges faced by family farms, particularly those led by women, and support their integration into the circular economy. The study further highlights the importance of aligning these financial instruments with supportive public policies to ensure a comprehensive and efficient approach to rural development. By leveraging such tools, family farms can be better equipped to face economic and environmental challenges while fostering long-term resilience and sustainability.

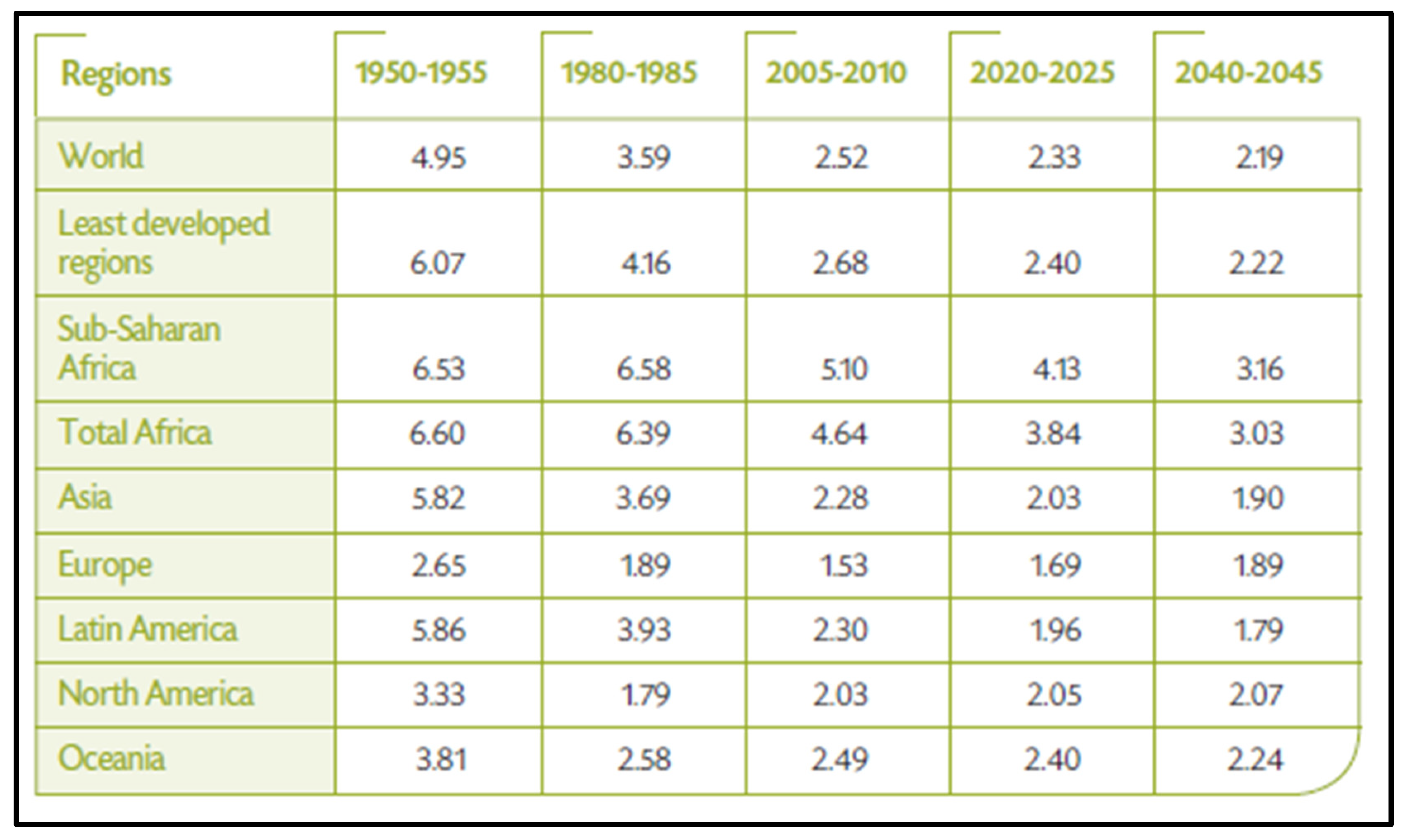

The Agricultural Population

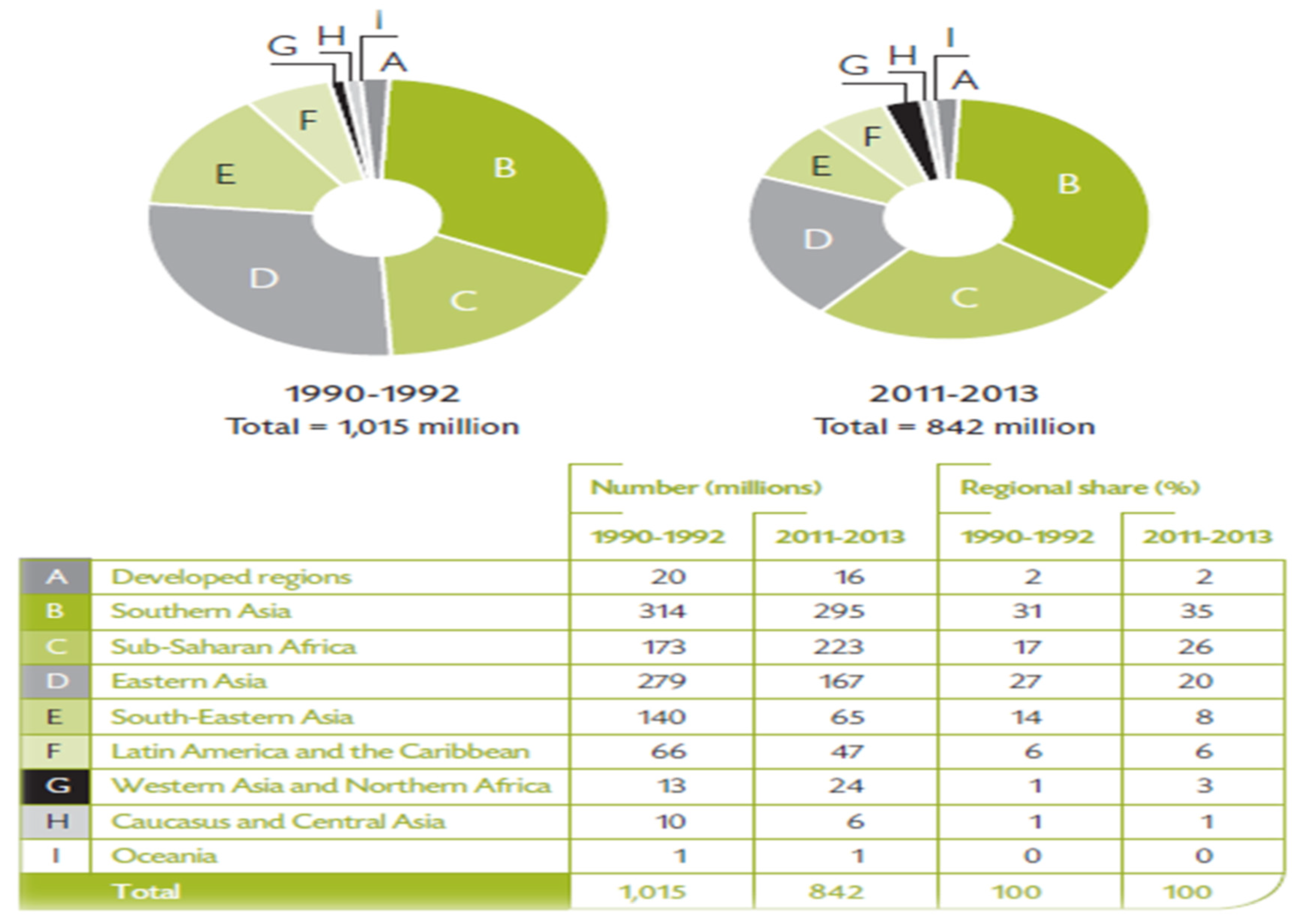

The agricultural population today stands at 2.6 billion people, representing nearly 40% of the world’s population. This includes 1.3 billion active workers, making agriculture the largest industry in the world, far surpassing all other industrial and service sectors, which are much more segmented and specific. The role of agriculture in global activity varies considerably depending on the regions of the world and their stage in the economic transition process.

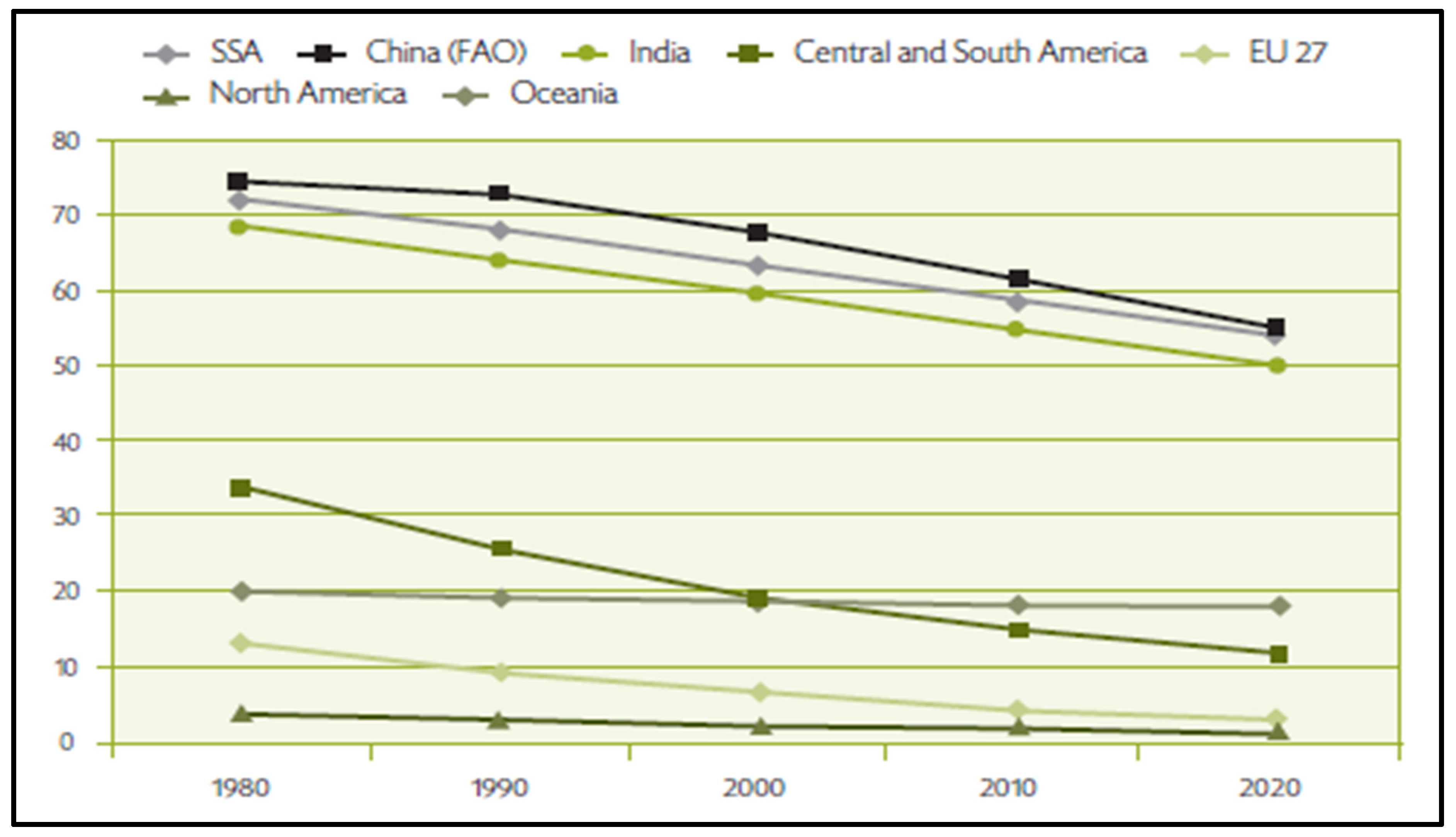

In Europe and North America, the first regions to initiate structural transformation, the proportion of active agricultural workers has fallen below 5%. However, the situation is much more contrasted in the rest of the world (see

Figure 1).

The number of active agricultural workers in Latin America has decreased by a factor of 2.5 since 1980 (-56%), whereas Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Asia, particularly India and China, have experienced a much slower decline (between -15% and -20%). These regions continue to maintain a high proportion of active agricultural workers (between 55% and 65%).

As a result, and due to the demographic weight of the vast Asian continent, agricultural workers are overwhelmingly concentrated in Asia (see Chart 2): 78% of the global total, or over one billion workers, including 497 million in China, 267 million in India, and 258 million in other Asian countries. With 15% of active workers (203 million), SSA is the second-largest agricultural region, while the “weight” of the rest of the world accounts for only 7% of the global total (83 million active workers).

Figure 2.

Geographical breakdown of agricultural workers in 2010. Source: FAOSTAT.

Figure 2.

Geographical breakdown of agricultural workers in 2010. Source: FAOSTAT.

Family Farms and Natural Resources

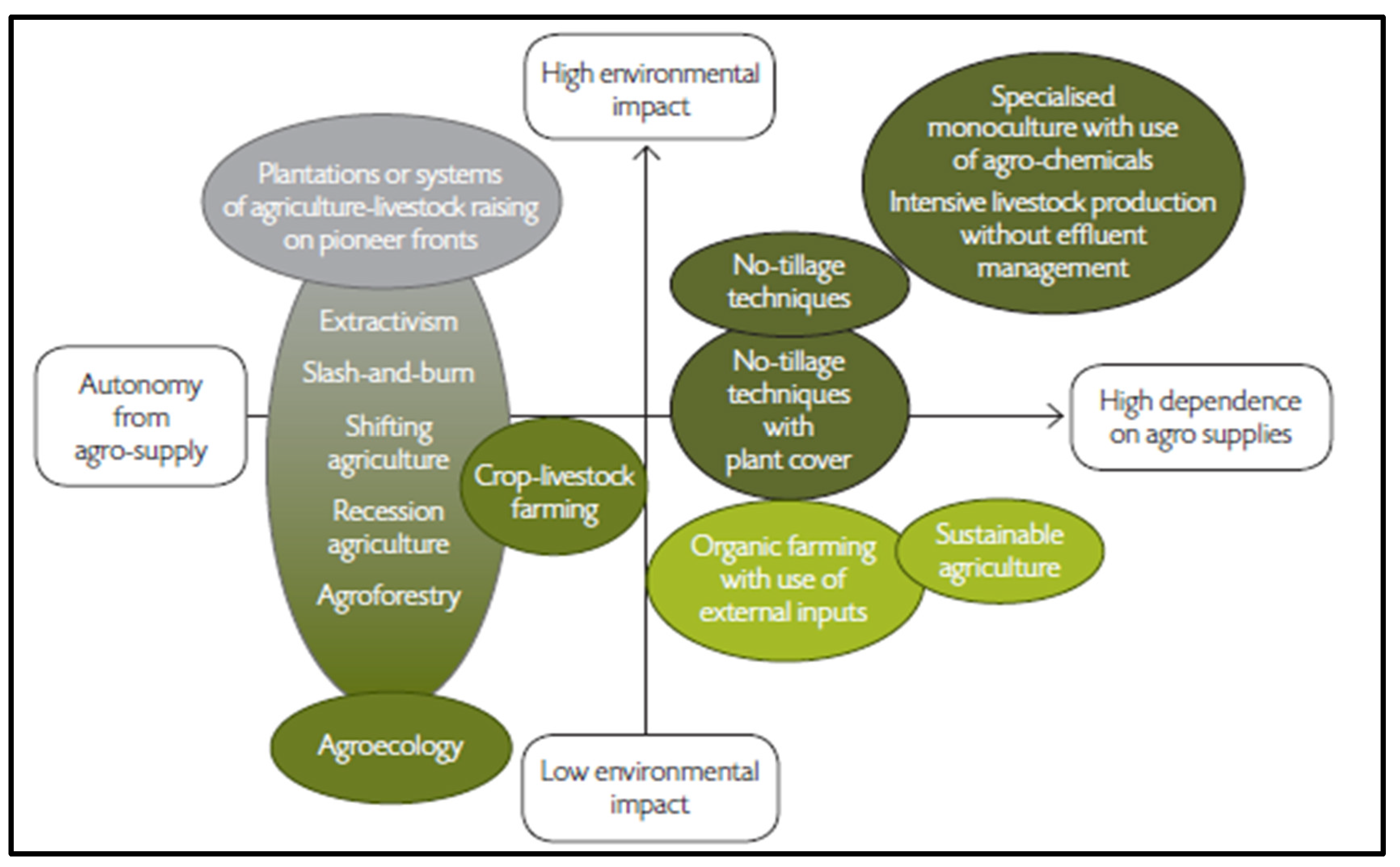

Do family farms contribute to the degradation or conservation of nature? Is the environmental impact greater or lesser than that of corporate farms? These questions, which are of particular importance today, often lead to partisan and passionate positions.

Family farm organizations, particularly producer organizations, rural associations, and farmer unions, along with their allies (universities, national and international NGOs), frequently argue that family farms ensure responsible management of natural resources, as their conservation ensures the sustainability of the production unit. Family farms, whose location and production intensity do not essentially depend on market signals, would thus seem to pay more attention to the environmental implications of their activities than corporate farms. Large producer organizations, however, do not share this analysis and often associate environmental degradation with family agriculture, citing the inefficiency of the latter’s techniques. Family farming can also generate diffuse pollution, which is difficult to address due to its geographical dispersion. This is, for example, the case with effluents from artisanal palm oil extraction, which are discharged into rivers in the Gulf of Guinea countries, while effluents from industrial oil mills must be treated according to national legislation. However, artisanal extraction continues to be key to olive oil development outside the supply areas of oil mills, as farmers have no other outlets for their production. Indeed, the issue of environmental impact is largely embedded in official representations of the causes of degradation and its assessment.

Figure 6.

Relative position of technical systems concerning their environmental impact and their dependence on agro-supply. Sourcea: May 2015 / Family Farming Around the World / ©AFD.

Figure 6.

Relative position of technical systems concerning their environmental impact and their dependence on agro-supply. Sourcea: May 2015 / Family Farming Around the World / ©AFD.

It is very important to take urgent action to combat climate change and assess its impact, including in the policy of innovative financial instruments.

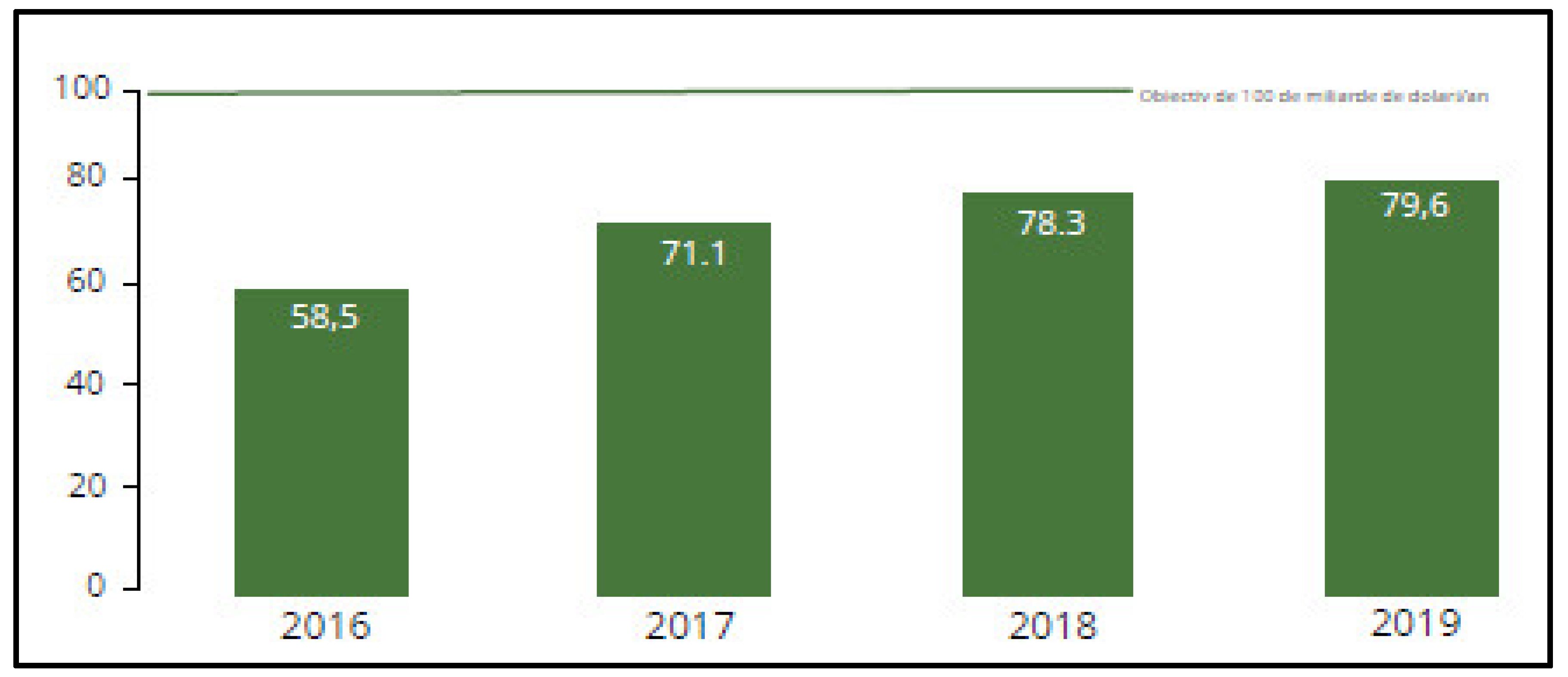

Figure 8.

Climate finance provided and mobilized for developing countries, 2016–2019 (billions of dollars). Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021. Climate Finance provided and mobilised by developed countries: aggregate trends updated with 2019 data. Paris: OECD.

Figure 8.

Climate finance provided and mobilized for developing countries, 2016–2019 (billions of dollars). Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021. Climate Finance provided and mobilised by developed countries: aggregate trends updated with 2019 data. Paris: OECD.

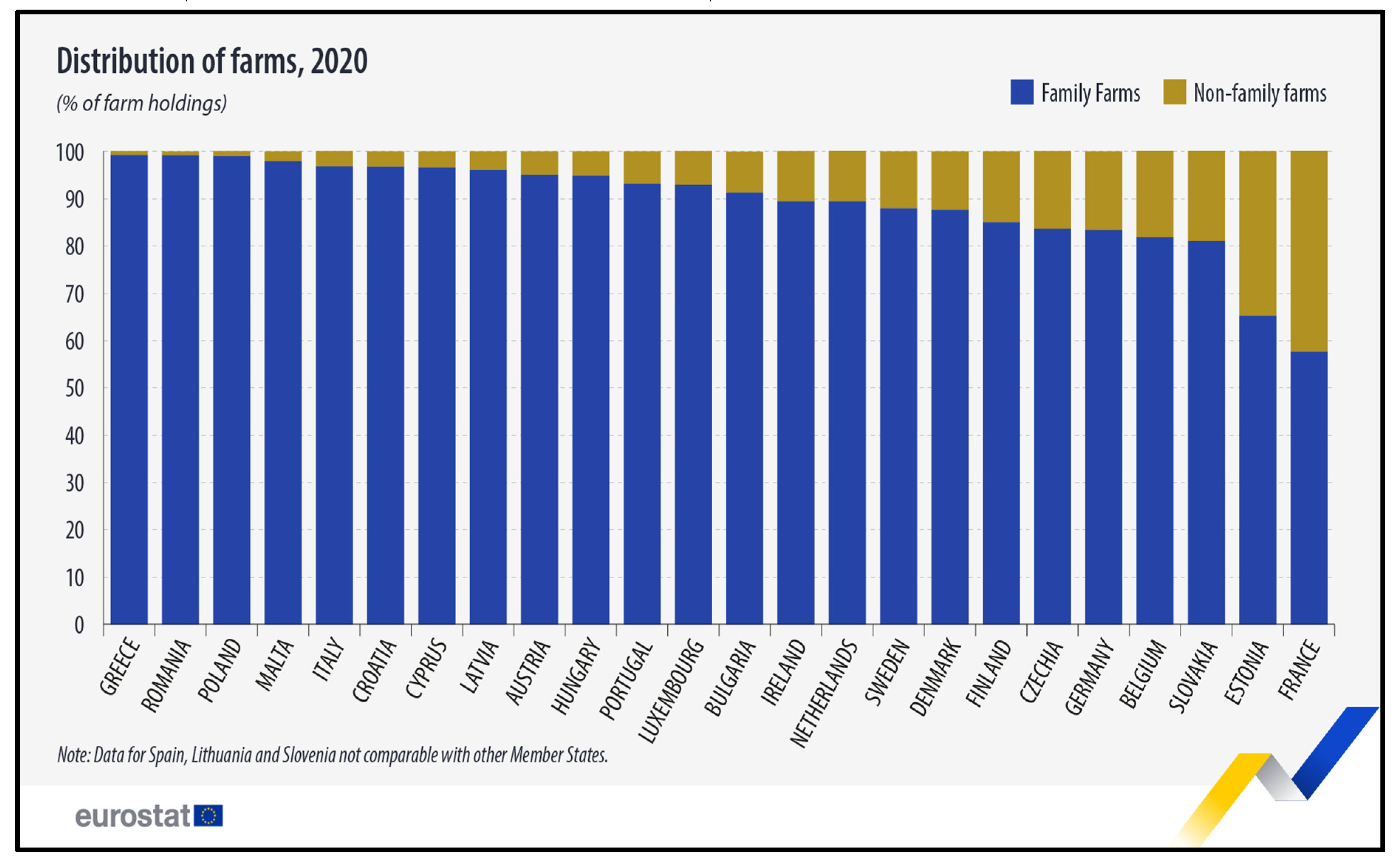

Eurostat published an analysis regarding the share of family farms in the EU for the year 2020. According to the statistics, 93% of the 9.1 million farms in the EU were family-run. Family farms are dominant in the agricultural structure in terms of the number of holdings, labor recruitment, and, to a lesser extent, the area of land cultivated. In Romania, 99% of all farms were family-run four years ago (in 2020).

In the European Union, in 2020, there were 9.1 million farms, with the overwhelming majority of them (about 93%) being classified as family farms (i.e., farms run by families where 50% or more of the agricultural labor force was provided by family members). Family farms dominate the agricultural structure in the EU in terms of the number of holdings, their contribution to agricultural employment, and, to a lesser extent, the area of land they cultivate and the value of the production generated, according to data published by Eurostat (

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20231024-2).

99% of the farms in Romania are family-run. Nearly 6 in 10 farms (about 57%) were managed solely by the owner and family members. For another 36% of farms, family contributions accounted for at least 50% of the total labor.

The majority of agricultural land used in 2020 was managed by family farms (about 61% of the 157.4 million hectares in use), the majority of total agricultural labor (nearly 78%), a majority of animal farms (nearly 55%), and standard production (about 56%).

Family farms accounted for at least 80% of all farms in all EU countries, except for Estonia (65%) and France (58%). The EU countries with the highest shares of family farms were Greece, Romania, and Poland (all with about a 99% share of all farms).

Figure 9.

Specific characteristics of the programming periods 2014-2020, respectively 2021-2027.

Figure 9.

Specific characteristics of the programming periods 2014-2020, respectively 2021-2027.

Figure 10.

Prezentarea domeniilor prioritare incluse în Planurile de redresare și reziliență la nivel național în perioada 2021-2025. Source: Data processing by the European Commission, 2020.

Figure 10.

Prezentarea domeniilor prioritare incluse în Planurile de redresare și reziliență la nivel național în perioada 2021-2025. Source: Data processing by the European Commission, 2020.

Relevant for defining the mechanism of Innovative Financial Instruments for Family Farms at the local level are the financial indicators of the population (primary and derived), and as an example, I mention:

Indicator: Financial Indebtedness Ratio of the Population (involved in family-type farms)

Symbol: Cip

Degree of synthesis: Derived indicator

Data source: Financial Accounts – BNR and Statistical Yearbook

Calculation formula: Cip = DTP / POP (1)

Explanation of the notation above:

DTP = total financial debts of the population, regardless of type (bank or non-bank), instrument, and institution, recorded at the end of the year.

POP = total population: a group of individuals united by citizenship ties and by establishing residence within the state’s territory, in relation to which the latter exercises its sovereign power. It represents the entire dataset from which a sample is selected, and with which the auditor wants to formulate conclusions, statistically evaluated at the end of the year, according to the data in the Statistical Yearbook.

Economic significance: The indicator highlights the financial debt per capita, the population’s borrowing capacity, which primarily depends on the quality of the financial system and the income level and purchasing power of the population. The indicator can be calculated either by stock or flow (debts incurred during the year).

Utility in economic analysis: It allows for an overall analysis, as well as by types of indebtedness (through derived detailed indicators) of the population’s borrowing capacity and enables a comparative analysis over time or space.

Use within the study: the indicator can be correlated with other generic indicators of savings and financial indebtedness of the population involved in family farms, as well as with specific indicators of the population’s financial condition. Additionally, the indicator can be integrated into the network of indicators evaluating the financial condition of the population involved in family-type farms, highlighting their interconnections and co-determinations in the perspective of a complex synthetic evaluation indicator.

Relevant for defining Innovative Financial Instruments for Family Farms at the local level are the financial indicators of the population (primary and derived), and as an example, I mention:Indicator: Financial Indebtedness Ratio of the Population (involved in family-type farms)

Table 6.

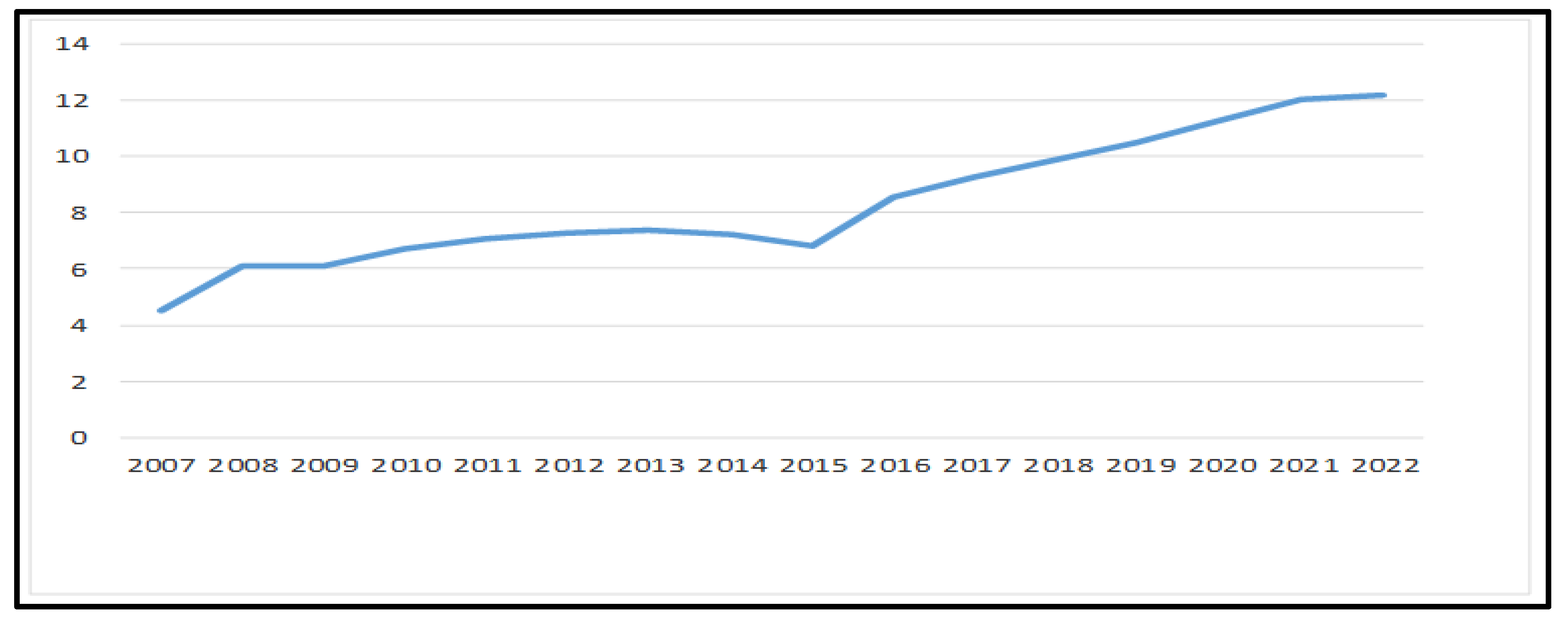

Evolution of the indebtedness ratio in the period 2007 – 2022.

Table 6.

Evolution of the indebtedness ratio in the period 2007 – 2022.

| indicator |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| DTP th.lei |

101479 |

137544 |

137835 |

151112 |

158433 |

163460 |

165072 |

161484 |

151870 |

189838 |

205594 |

219986 |

233185 |

249,508 |

265831 |

267293 |

| POP th loc |

22562 |

22542 |

22516 |

22481 |

22434 |

22391 |

22346 |

22298 |

22242 |

22223 |

22215 |

22197 |

22175 |

22142 |

22047 |

21943 |

| Cip th lei/loc |

4,50 |

6,10 |

6,12 |

6,72 |

7,06 |

7,30 |

7,39 |

7,24 |

6,83 |

8,54 |

9,25 |

9,91 |

10,52 |

11,27 |

12,05 |

12,18 |

Figure 11.

Evolution of the population’s debt ratio during the period 2007 – 2022. Source: Own processing based on data published by the National Bank of Romania (from National Financial Accounts 2007 - 2021 and monthly bulletins from 2007 - 2023) and the National Institute of Statistics (Statistical Yearbook of Romania, 2007 - 2022 editions, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, 2007 - 2023, Press Releases), Financial Stability Report, 2007-2022 editions, BNR, Bucharest.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the population’s debt ratio during the period 2007 – 2022. Source: Own processing based on data published by the National Bank of Romania (from National Financial Accounts 2007 - 2021 and monthly bulletins from 2007 - 2023) and the National Institute of Statistics (Statistical Yearbook of Romania, 2007 - 2022 editions, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, 2007 - 2023, Press Releases), Financial Stability Report, 2007-2022 editions, BNR, Bucharest.