1. Introduction

Vortex-induced vibration (VIV) is a common phenomenon in various engineering structures, including the cables of long-span bridges [

1,

2,

3], wind turbine towers [

4,

5], and risers of offshore platforms [

6,

7]. When a bluff body is placed in a flowing fluid, alternating vortex shedding occurs on both sides of the boundary layer. This vortex shedding causes periodic variations in the lift and drag forces acting on the body, which, in turn, induces vibrations in the structure. The interaction between the fluid and the structure is referred to as VIV [

8]. When the vortex-shedding frequency approaches the structure’s natural frequency, the vibration amplitude may increase dramatically, potentially causing fatigue failure and posing a significant threat to the structural integrity, thereby reducing the structure's service life [

9].

The investigation of VIV can be approached through various methods, including experimental research [

10,

11], semi-empirical models [

12,

13], and numerical simulation [

14,

15]. Experimental studies enable the observation of phenomena through physical models and the collection of data; however, this approach is costly and time-consuming due to the need for model fabrication. Based on experimental data and theoretical research, several semi-empirical models were proposed to predict the VIV characteristics [

16]. With advancements in computational technology, numerical simulations have become a crucial tool for VIV research, including methods like Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) [

17,

18], Large Eddy Simulation [

19,

20], as well as Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) models [

21,

22,

23]. Numerical simulations offer a cost-effective means to address most VIV problems and can precisely predict both the flow field and structural motion. Nevertheless, numerical simulations require significant computational resources, making efficient predictions a challenge [

24], when dealing with high Reynolds number turbulent flows and complex geometries. Therefore, accurately and efficiently solving VIV problems remains a highly demanding task.

Deep learning (DL), as one of the core research areas in AI, has been widely applied across various industries [

25]. Compared to traditional machine learning, deep learning offers superior data processing capabilities. As the volume of data increases, the performance of deep learning models improves substantially, whereas traditional machine learning models tend to stabilize after a certain threshold, beyond which no further improvement occurs [

26]. Deep learning is particularly effective at nonlinear fitting, allowing for the adjustment of network architectures through combinations of linear and nonlinear modules. In theory, it can map any function and solve complex problems in high-dimensional data [

27]. In fluid dynamics, the application of deep learning has been growing, offering approximate solutions to a range of fluid dynamics problems [

28]. Jin et al. [

29] proposed a data-driven model integrating Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), using pressure data around a cylinder at different Reynolds numbers to predict the velocity field. Sekar et al. [

30] built a data-driven method combining CNN and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) for rapid flow field prediction. Kim et al. [

31] utilized existing experimental data and deep neural networks to model VIVs of a cylinder, significantly reducing the need for experimental data. However, data-driven models require large amounts of training data to ensure predictive accuracy and are often not robust to noisy data [

32]. Moreover, since these models do not incorporate physical prior knowledge, they lack interpretability and cannot provide guarantees of convergence [

33].

To elevate the interpretability and robustness of data driven models and reduce their reliance on large datasets, Raissi et al. [

33] introduced prior knowledge into the DL framework, proposing the Physics Informed Neural Network (PINN) to solve problems about partial differential equations. Through incorporating a physical information loss term into the loss function, PINN remarkably improves model performance in data-scarce scenarios. The implementation of this approach makes PINN capable of better capturing and simulating physical phenomena with fewer training data, improving the model’s predictive accuracy and reliability. Raissi et al. [

34] incorporated the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations as physical constraints in PINN, utilizing spatiotemporal data of both velocity field and structural motion to reconstruct the fluid’s velocity and pressure fields, as well as to infer the lift and drag forces acting on the structures. Cheng et al. [

35] integrated the RANS equations (with additional viscosity parameters) into the loss function to solve VIV and wake-induced vibrations (WIV) at various reduced velocities in turbulent flows. Tang et al. [

36] proposed a Transfer Learning-Physics-Informed Neural Network to study VIVs of cylinders, leveraging transfer learning to reduce PINN's dependence on large datasets and thus lower training costs. Zhu et al. [

37] applied PINN to learn VIV response data under varying stiffness conditions, enabling the prediction of VIV responses and the inference of structural stiffness. The PINN loss function combines data loss and various physical information losses with fixed weights. This approach enables PINN to simultaneously learn from data while embedding physical laws, improving both its predictive capability and generalization. However, during training, the gradients of the various loss terms in the PINN loss function can vary significantly during backpropagation, resulting in imbalanced training of each loss component. Wang et al. [

38] identified this issue and explored potential solutions.

To elevate the performance and robustness of PINNs in solving complicated problems, many researchers have proposed different optimization algorithms. Xiang et al. [

39] introduced an optimization algorithm for PINNs that automatically updates the weights in the training process. This method constructs a Gaussian probabilistic model, defines the loss function based on maximum likelihood estimation, and validates its effectiveness and robustness by solving classical partial differential problems. Chen et al. [

40] delved into the impact of various weightings on PINN’s solution of the Richards-Richardson equation (RRE) and proposed a principled loss-function-based method that automatically adjusts the loss function weights without needing any hyperparameters, lowering PINN’s reliance on the initial weight settings. Tarbiyati et al. [

41] trained and determined the initial weights of PINNs by solving partial differential equations with finite difference methods, and used the equation solutions to enhance the performance. In the application of PINNs to solve the Navier-Stokes equations, researchers have also proposed optimization algorithms. Li et al. [

42] were inspired by the minmax algorithm and introduced a dynamic weighting strategy for solving both the forward and inverse issues of the Navier-Stokes equations. This strategy identifies the difficulty level of the training data and adjusts the weights of more difficult data to accelerate the training process, balancing the contributions of various data loss terms to the network. Hou et al. [

43] proposed an adaptive loss balance PINN (LB-PINN) to reconstruct the propeller wake flow field. Through introducing adaptive weights, this method balances the different losses in the network, elevating the flow field reconstruction accuracy. Shi et al. [

44] framed PINN as a multi task learning problem and introduced a method that automatically adjusts loss weights, balancing the training speed of different loss components and stabilizing the network’s training process.

In this study, we explore an Adaptive Weight Physics-Informed Neural Network (AW-PINN) incorporating the principles of multi-task learning. The neural network's training process is enhanced by AW-PINN's integration of the Gradient Normalization (GradNorm) algorithm to elevate the model's capacity to predict complicated phenomena in fluid dynamics. In AW-PINN, we use the gradient norm of the weight loss function with respect to the hidden layer weights of the network as the indicator for the training speed, and the average of the gradient norm of all weight loss terms as a common scale. AW-PINN adjusts the training speed of each loss term by the regulation of the weights of different loss components and adjusts their contribution to overall training. The network slows down its own training speed when the gradient norm of a certain loss term surpasses the target gradient norm, thereby reducing the weight of a particular loss term, so that all of the loss components can be trained at a comparable rate. We apply PINN, AW-PINN, and other optimization algorithms to different VIV datasets. Through comparisons of test errors across multiple datasets, we demonstrate that AW-PINN outperforms the other algorithms in performance and exhibits superior stability compared to other PINN optimization methods. The remainder of this research is organized as follows:

Section 2 delivers a detailed description of the cylinder VIV problem, along with the principles behind PINN, GradNorm, and AW-PINN;

Section 3 presents the training of various network models using datasets generated from numerical simulations, and verifies the stability of these models using additional datasets;

Section 4 concludes the study.

2. Problem and Model

2.1. Research Problem

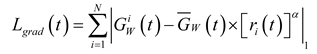

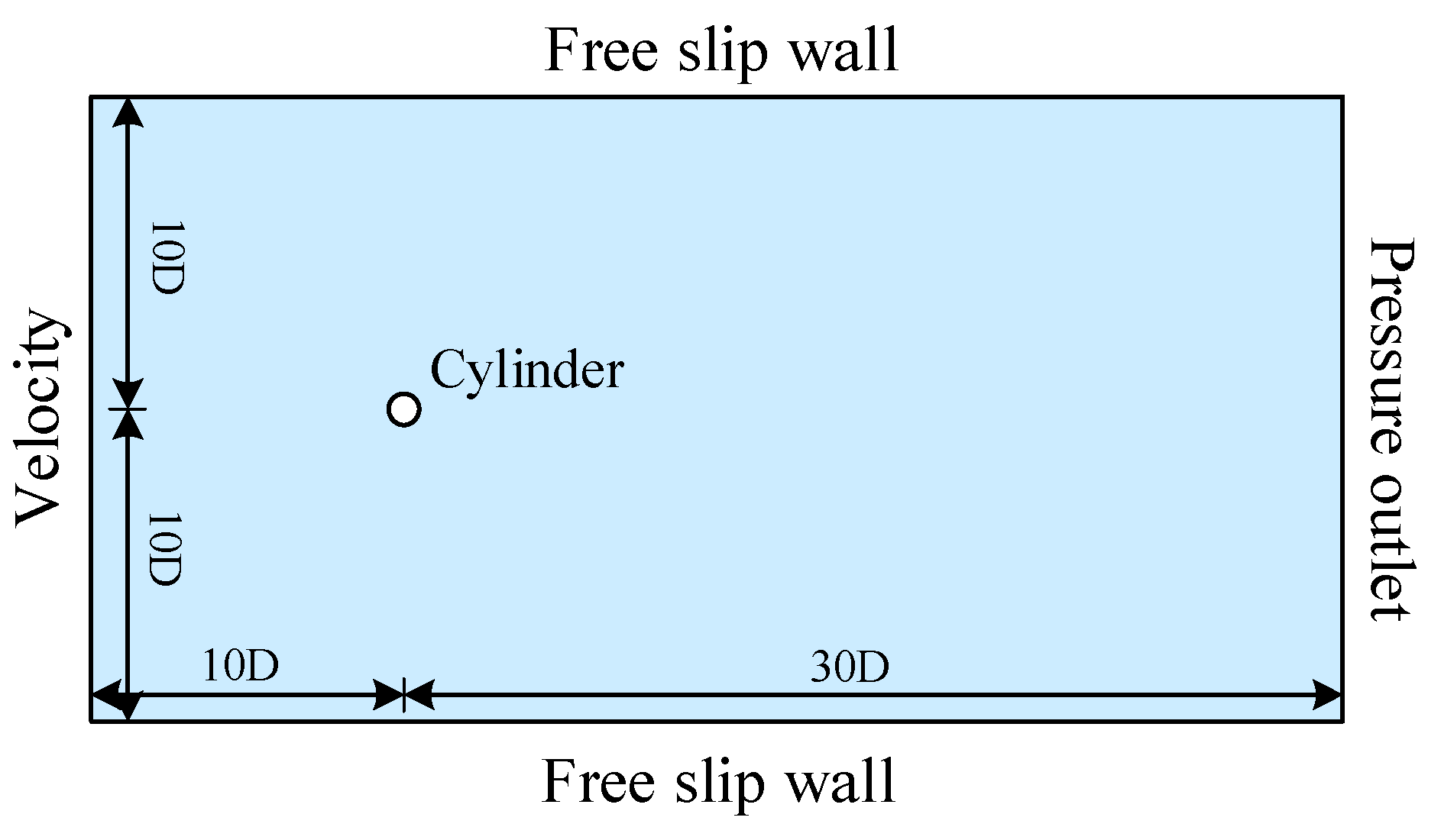

This study focuses on cylindrical structures, which are widely used in engineering, and investigates the application of the AW-PINN to solve the problem of VIV in cylinders. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the study considers a two-dimensional elastically supported cylindrical structure and analyzes the two-dimensional VIV problem. The cylinder is simplified as a mass-spring-damping system that can move freely in both the streamwise direction (x-direction) and the transverse direction (y-direction).

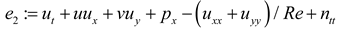

In the rectangular coordinate system, the origin is set at the center of the cylinder, and a moving reference frame, which moves along with the cylinder, is established. The continuity equation for incompressible fluid as well as the momentum conservation equation (Navier-Stokes equations) [

45] in the moving reference system are given by:

where

u and

v represent the streamwise and transverse velocities of the flow field;

p is the pressure in the flow field, and

and

are the streamwise as well as transverse displacements of the cylinder.

Re is the dimensionless parameter, which characterizes the fluid flow behavior.

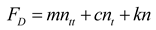

The structural dynamics governing equation for the motion of the cylinder is given by:

where

FD and

FL denote the drag and lift forces acting on the cylinder;

m signifies the mass of the cylinder;

c and

k represent the damping and stiffness of the cylinder.

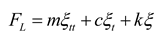

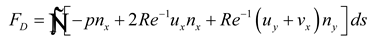

After reconstructing the velocity and pressure fields, the lift and drag forces acting on the cylinder can be inferred from the velocity gradients and the pressure field, as expressed in the following equation:

where

nx and

ny are the outward normal components of the cylinder's surface;

ds is the arc length of the cylinder's surface.

2.2. Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN)

A PINN is essentially a deep neural network (DNN) augmented with physical prior knowledge, enabling it to accurately approximate any continuous function. In the training of a PINN, partial differential equations (PDEs) residuals at specified points in the computational domain, along with the initial and boundary conditions are added to the loss function. This ensures that the predicted results align with the prior knowledge embedded in physical laws. The training of a PINN is not only data driven, but also constrained via physical principles, thereby enhancing the model's precision and reliability. Compared to traditional DNNs, PINNs reduce dependence on the training dataset, enhance the interpretability of the network model, and demonstrate superior generalization capabilities. Leveraging the widely-used automatic differentiation technique in DNNs, PINNs can accurately compute the derivatives of network outputs with respect to input variables, which facilitates the calculation of the PDE residuals to serve as physical constraints.

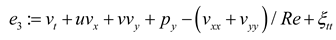

The objective of this research is to build the flow field of two-dimensional VIV, and predict the displacement of a cylindrical structure in the absence of flow field pressure data. The physical prior knowledge of PINN consists of the continuity equation and the momentum conservation equation (Navier-Stokes equations) for incompressible fluids, as shown in equations (1a), (1b), and (1c). Here,

,

, and

represent the residuals of the three physical equations, as detailed below.

where,

x and

y are spatial variables;

t is the time variable. The velocity and pressure of the flow field, with respect to spatial and temporal derivatives, are nonlinear differential operators, which are computed by the neural network through automatic differentiation techniques.

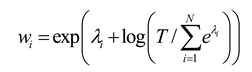

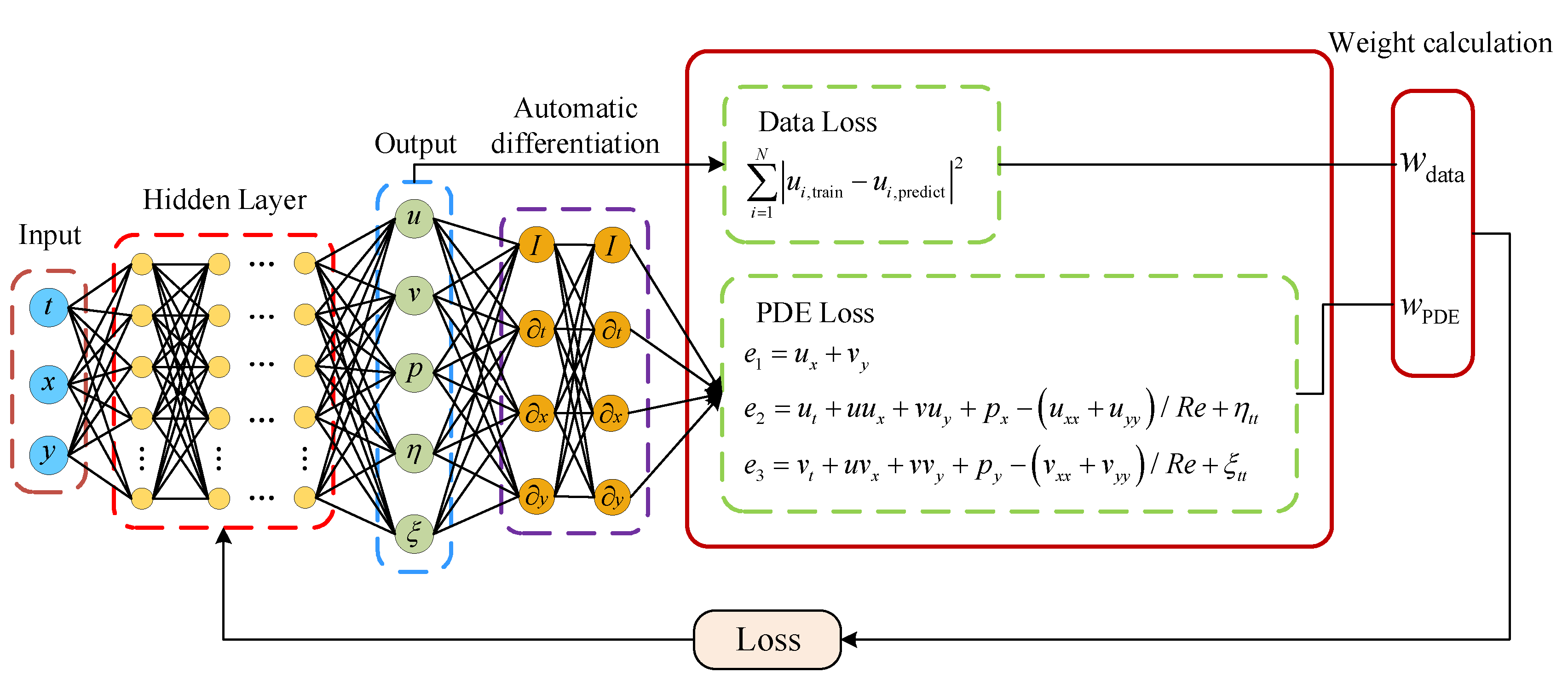

The structure of the PINN used for two-dimensional VIV of a cylindrical body is displayed in

Figure 2, where the physical constraints of the continuity equation and the Navier-Stokes equations are incorporated into a fully connected network. The network architecture employed in this research is built upon the design proposed by Cheng et al. [

35]. The PINN consists of a 14-layer neural network, encompassing an input layer, an output layer, as well as 12 hidden layers, with each hidden layer containing 64 neurons. The network weights are initialized via Xavier initialization, while the biases are initialized to 0. The activation function chosen is the sine function to introduce nonlinearity. The inputs to the network include spatial coordinates (

x,

y) and time

t, and the outputs of the network are the downstream velocity

u, lateral velocity

v, pressure

p of the flow field, and the downstream displacement

and lateral displacement

of the cylindrical body. The loss function is composed of two components: the data loss and the equation loss. The data loss is the error between the predicted values of the neural network and the data set, which includes four components: downstream velocity

u, lateral velocity

v, downstream displacement

n, and lateral displacement

r. By calculating the network outputs and various partial derivatives, we substitute these results into the governing equations, which allows us to compute the equation losses

,

, and

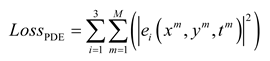

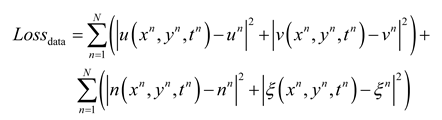

of the partial differential equations. The PINN loss function is as follows:

where

N is the number of training data points in the dataset;

M is the number of configuration points for the equation losses.

represents the data loss, and

represents the equation losses for the three physical equations.

2.3. GradNorm Algorithm

The loss function of the PINN encompasses both data loss and the residual losses of different physical equations. The gradients of these different losses during backpropagation can vary significantly, which may lead the model to focus disproportionately on certain losses while neglecting others. This can lead to poor convergence speed of the model as well as inadequate performance of the model in prediction. In order to elevate the model's learning capacity, we need to properly weight these different losses, which means we need to balance their gradients, and make the training more uniform. As a result, the multi task learning algorithms from computer vision can be utilized during the training of the PINN to increase the stability of the network model.

In multi-task learning, simply summing the losses of varying tasks to form the total loss does not account for the varying contributions of each task's backpropagation gradients to the network model. When there are significant discrepancies between the gradients of different tasks, those with smaller gradients may not receive sufficient learning, preventing a balance in the losses across tasks. Introducing fixed weights in the loss function can help balance these gradient differences, but assigning small weights to high gradient tasks will unnecessarily limit the learning of tasks, which ultimately impedes the effective learning of tasks with larger gradients. To solve this issue, in multi-task learning optimization, regarding the task weights as trainable parameters enables the model to automatically adjust the weights during training in response to variations in task gradients, ensuring a more balanced learning process for all tasks.

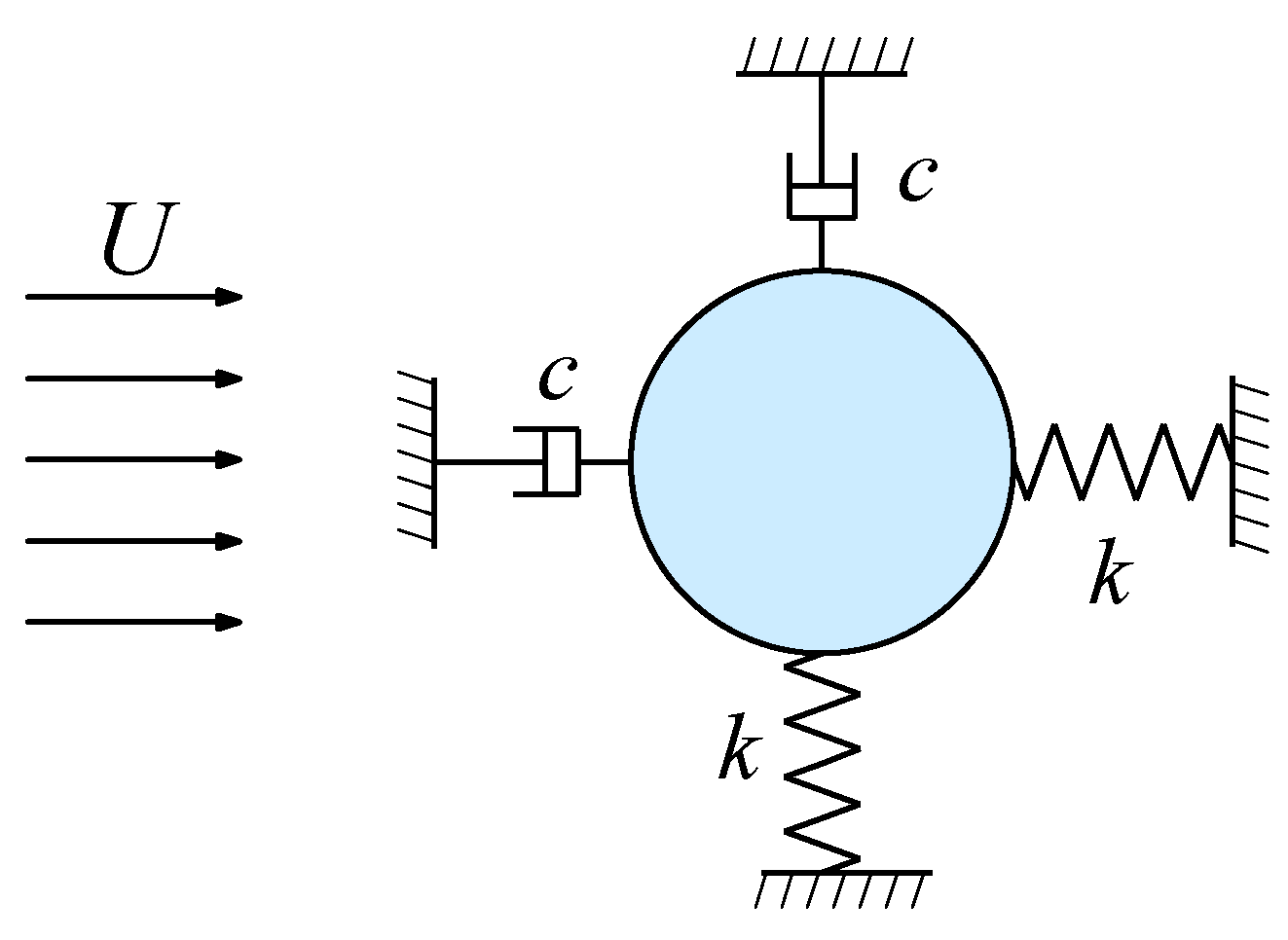

In this study, we propose a PINN with adaptive weights for solving the vortex-induced vibration problem, building on the GradNorm algorithm for multi-task optimization in computer vision [

46]. The GradNorm algorithm adjusts the weight of each task dynamically in the process of training, so that the contributions of varying loss components in the overall loss function are balanced, making the model learn each task more evenly. In particular, the GradNorm algorithm compares the actual gradient norm of a task with the target gradient norm of each task, and accordingly scales the task weights. When the actual gradient norm of a task exceeds the target gradient norm, the algorithm reduces the weight of that task, allowing tasks with larger actual gradients to receive smaller weights, while tasks with smaller gradients are assigned larger weights. This approach allows the model to balance gradient norm across all tasks, so that all tasks learn at a similar rate. The implementation of the GradNorm algorithm’s loss function is as follows:

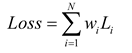

In the algorithm, the multi task loss function is a linear function of the single-task losses, and the loss function is as follows:

where

N is the number of tasks,

w and

Li are the single-task weights and losses.

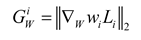

The gradient norm of the weighted loss for a single task is as follows:

where

signifies the gradient norm of the weighted loss

with respect to the network weights

, and

is a subset of the neural network weights. To save computational resources, the weights of the last shared layer are selected.

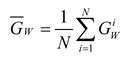

The average gradient norm is the mean value of the gradient norms across all tasks, given by:

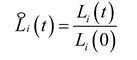

The loss ratio and relative inverse training rate for a single task at the

t-th iteration are:

Where

is the loss of task

i at the

t-th iteration;

is the initial loss of task

i.

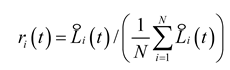

The average gradient norm

serves as the scaling factor for the gradient norms of different tasks, allowing the relative size of the gradients to be determined. The relative inverse training rate

of a task helps balance the task gradients. If

is larger, the training speed of the task will be slower, so the weighted gradient of the task should be higher to accelerate the task's training speed. The loss function of GradNorm is the sum of the L1 norms of the differences between the actual gradient norms and the target gradient norms of all tasks, as shown in the following equation:

where

is the target gradient norm for task

i, and

is a network hyperparameter representing the strength of the adjustment to align the tasks with the average training rate. The larger

is, the stronger the constraint on the balance of the training rate.

After the loss function for the weights is obtained, is calculated, and the task weights are updated using backpropagation. After each weight update, the weights are re-normalized by setting .

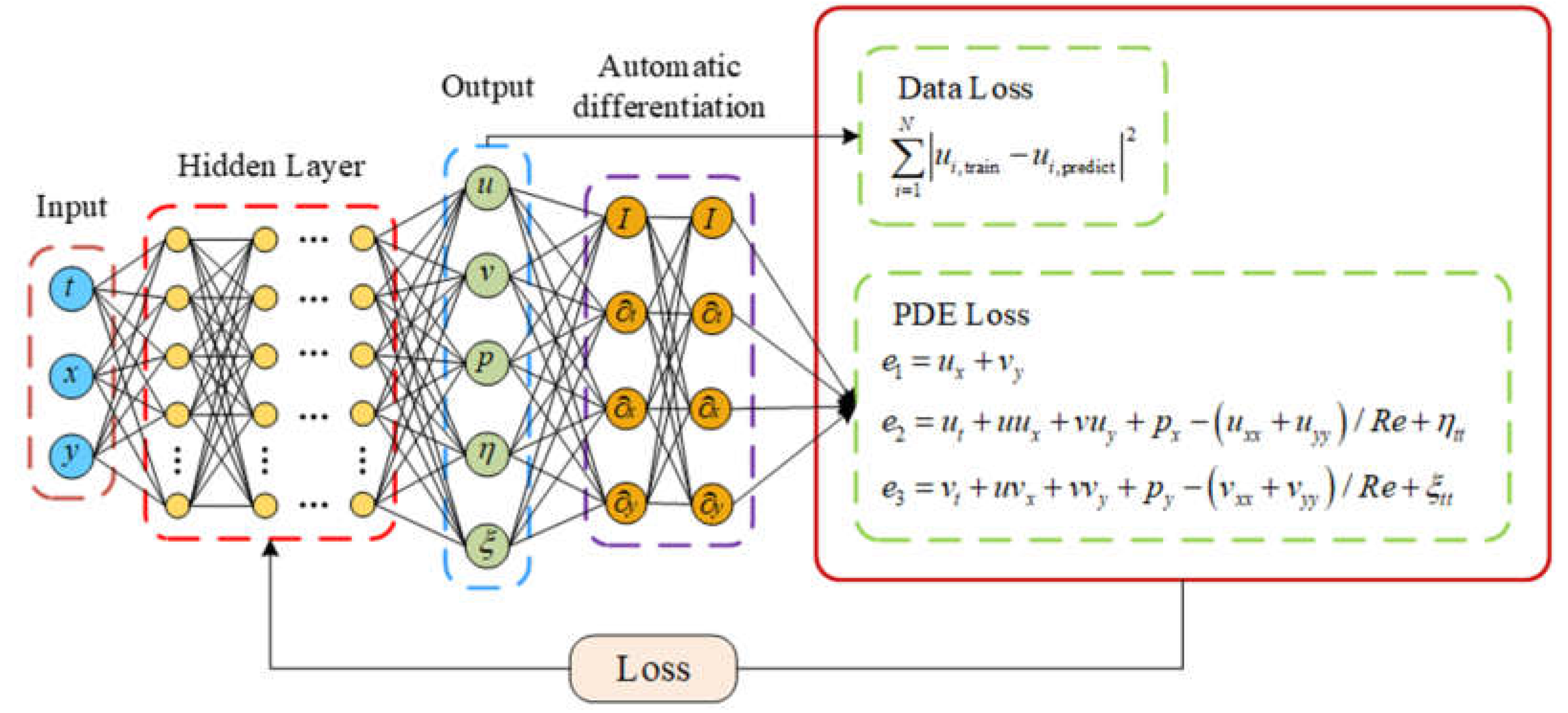

2.4. Adaptive Weight Physics-Informed Neural Network (AW-PINN)

Building on the work presented in this study, we introduce an improved version of the GradNorm algorithm, which is applied as a multi-loss training method for PINNs. The proposed model, AW-PINN, automatically adjusts the weights of each task during training, ensuring that the learning rates are balanced across tasks without favoring any single one. By adopting this approach, we enhance the overall capability of the model to learn effectively. The implementation of AW-PINN is outlined as follows.

The task losses following the initialization of a PINN exhibit considerable uncertainty. Directly employing the initial task losses as for computing the relative inverse training rates may prevent the algorithm from accurately determining these rates, leading to significant uncertainty in the performance of AW-PINN. To address this, we perform pre-training with equal weights before applying the GradNorm algorithm, which makes the network achieve a stable initialization. Employing task losses after pretraining, represented as , effectively reduces the performance uncertainty caused by initialization. Moreover, appropriate pre-training can improve the model’s learning ability and enhance its predictive performance.

In the GradNorm algorithm, the task weights are updated by computing

and then employing backpropagation to update the weight of task

i. This weight update approach does not impose any constraints on the sign of the weights. However, in AW-PINN, the weights may become negative, resulting in negatively weighted task losses that adversely affect the model's training process. To ensure that the task weights remain positive throughout training, we define the weights as an exponential function, as follows:

where

is an intermediate value representing the task weight. By computing

, and updating

for task

during backpropagation, the updated task weight can be obtained. The total sum of task weights is normalized to the number of tasks using Eq. (15), ensuring that the influence of individual tasks remains balanced during training and preventing any imbalance issues. The AW-PINN algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Adaptive Weight Optimization Algorithm for PINN (AW-PINN) |

Step 1: Initialization

Initialize network weights and biases

Initialize task weights .

Select the value of α and designate the shared layer (the last hidden layer).

Step 2: Pre-training with Equal Weights

For iteration from the first to the n-th iteration:

Calculate .

Train the network with equal weights.

Step 3: Training with Adaptive Weighting Method

At the n-th iteration, proceed as follows:

Compute the total loss

Calculate , ,, and .

Compute

Compute , and

Update the loss weights with , and update the network weights using .

Set ), and re-normalize .

End.

|

The AW-PINN model architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3. After completing the PINN training, the data loss and equation loss are obtained. The hidden layers of the network serve as shared layers, with the last hidden layer selected to compute the gradient norm loss. This loss is then used to update the task weights for the subsequent iteration. The loss function of AW-PINN is as follows:

4. Conclusions

This study presents an Adaptive Weight Physics-Informed Neural Network (AW-PINN), designed to enhance the overall performance of the network model by adjusting the training speed of different loss terms, thereby balancing the model's learning process. The model optimizes the training speed of various loss terms by automatically adjusting the weight values, which in turn adapts the gradient magnitudes of the shared layers in the network. The study applies four models to different datasets and compares their results with numerical simulation data, leading to the following conclusions:

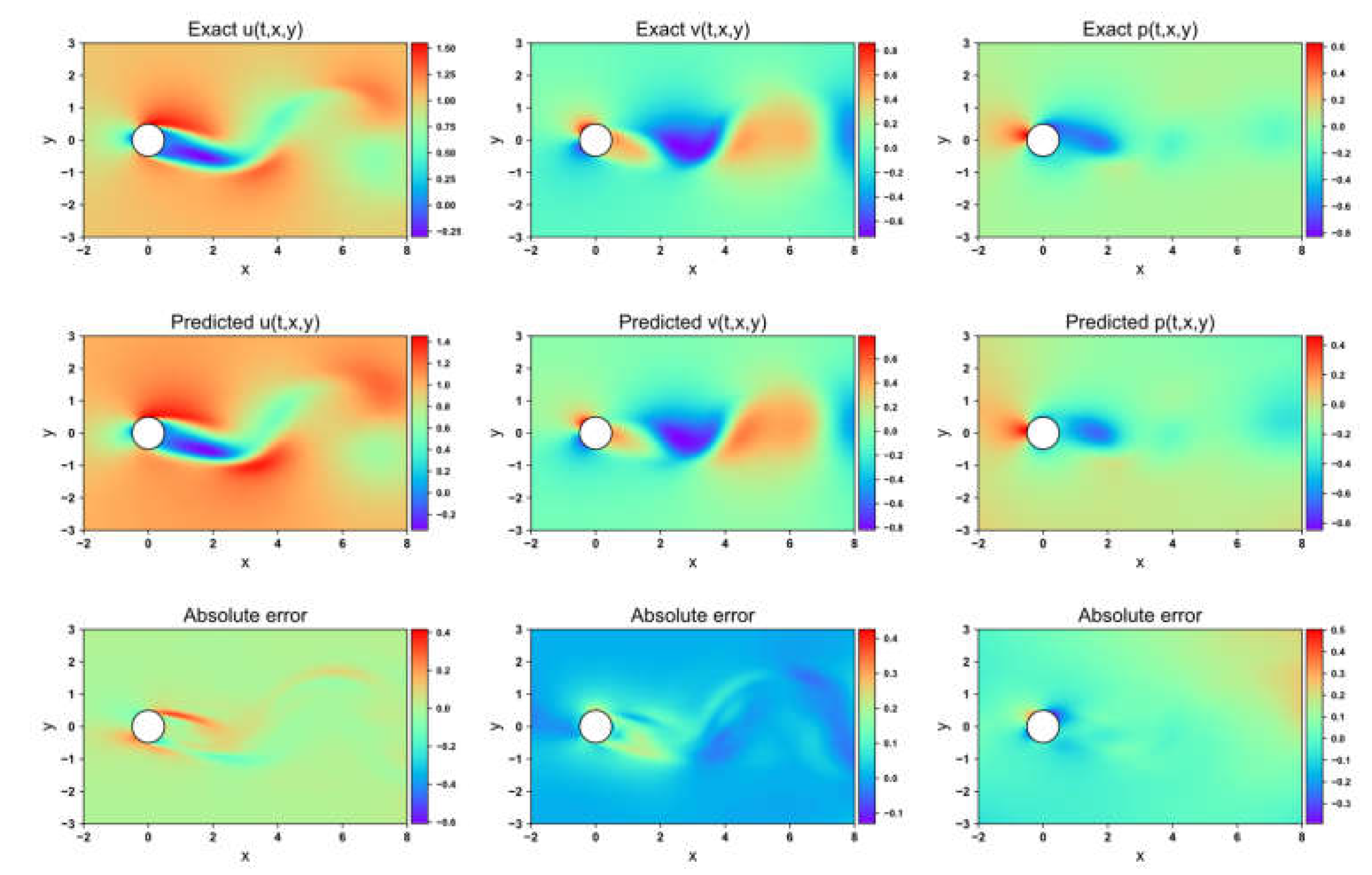

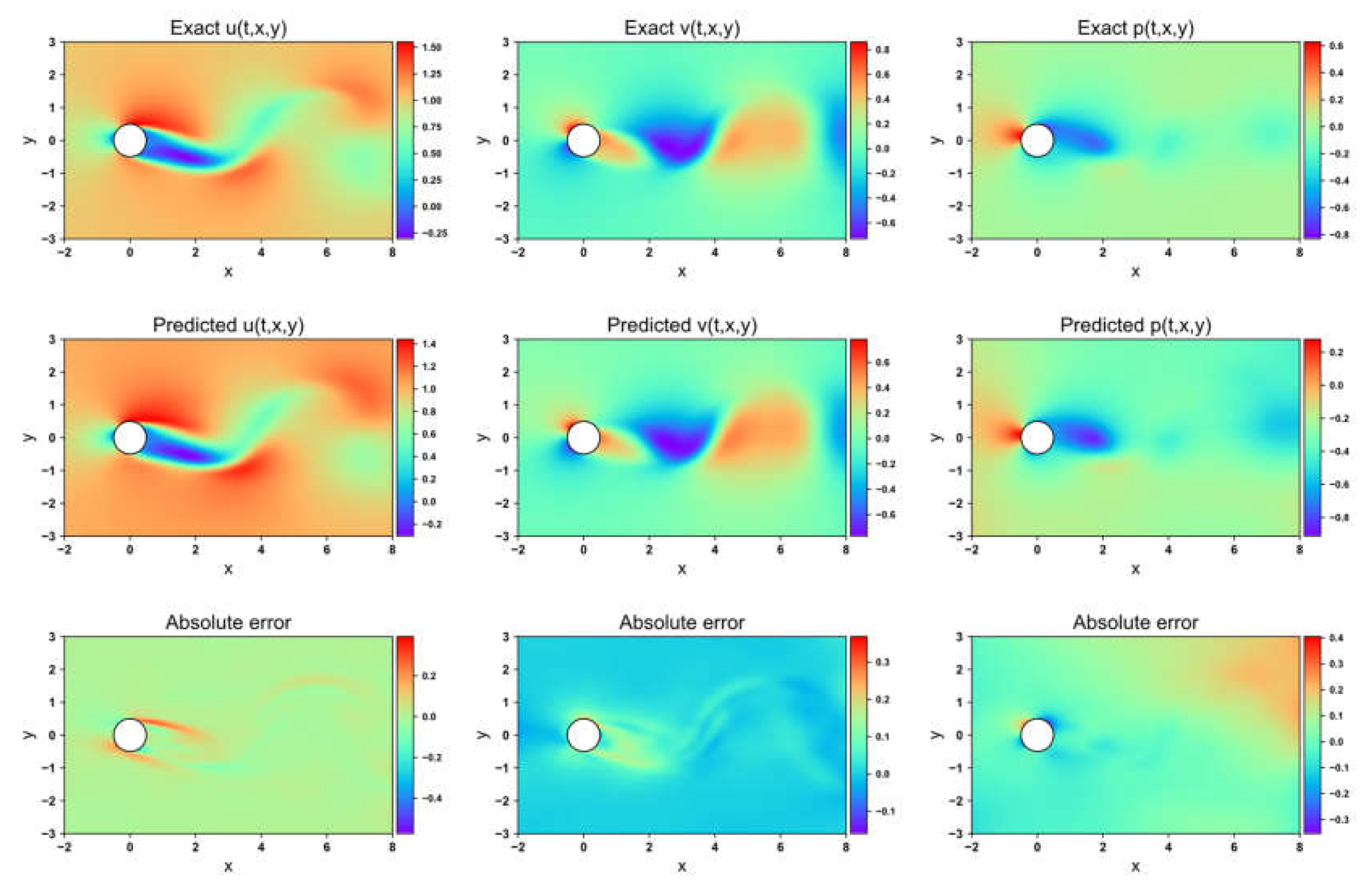

(1) The PINN model can utilize a limited amount of velocity data as the training set to accurately reconstruct the velocity and pressure fields of the VIV problem. Due to the absence of pressure data and the characteristics of the Navier-Stokes equations in the dataset, the pressure field reconstructed by PINN exhibits a constant difference in mean pressure compared to the numerical simulation results. However, it is capable of accurately predicting the distribution trend of the pressure. Additionally, the mean squared errors of the reconstructed velocity and pressure fields by PINN both converge to the order of 10-3.

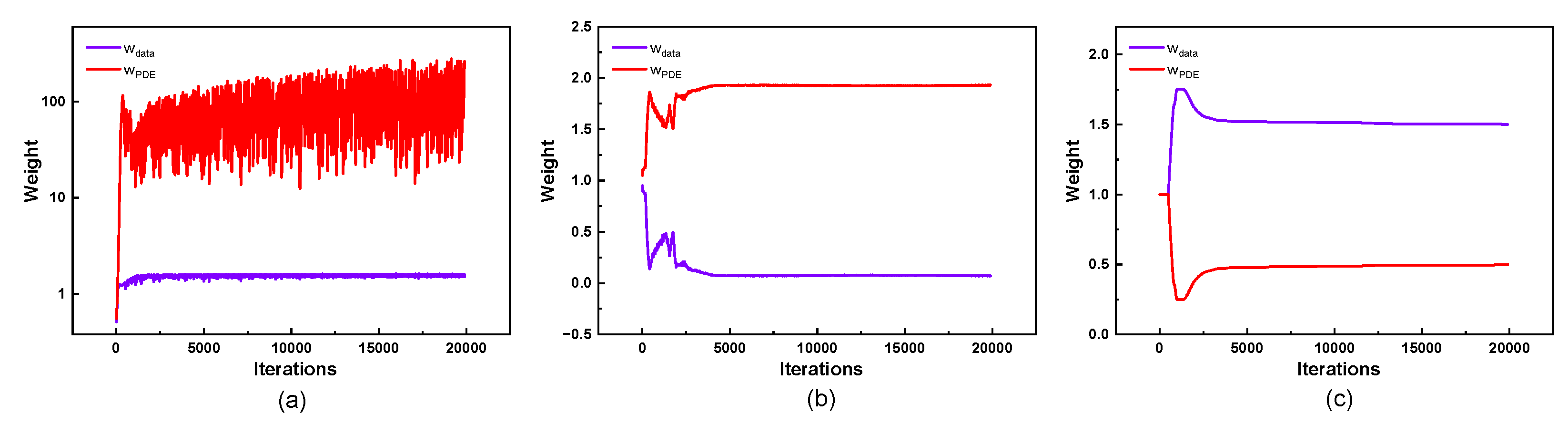

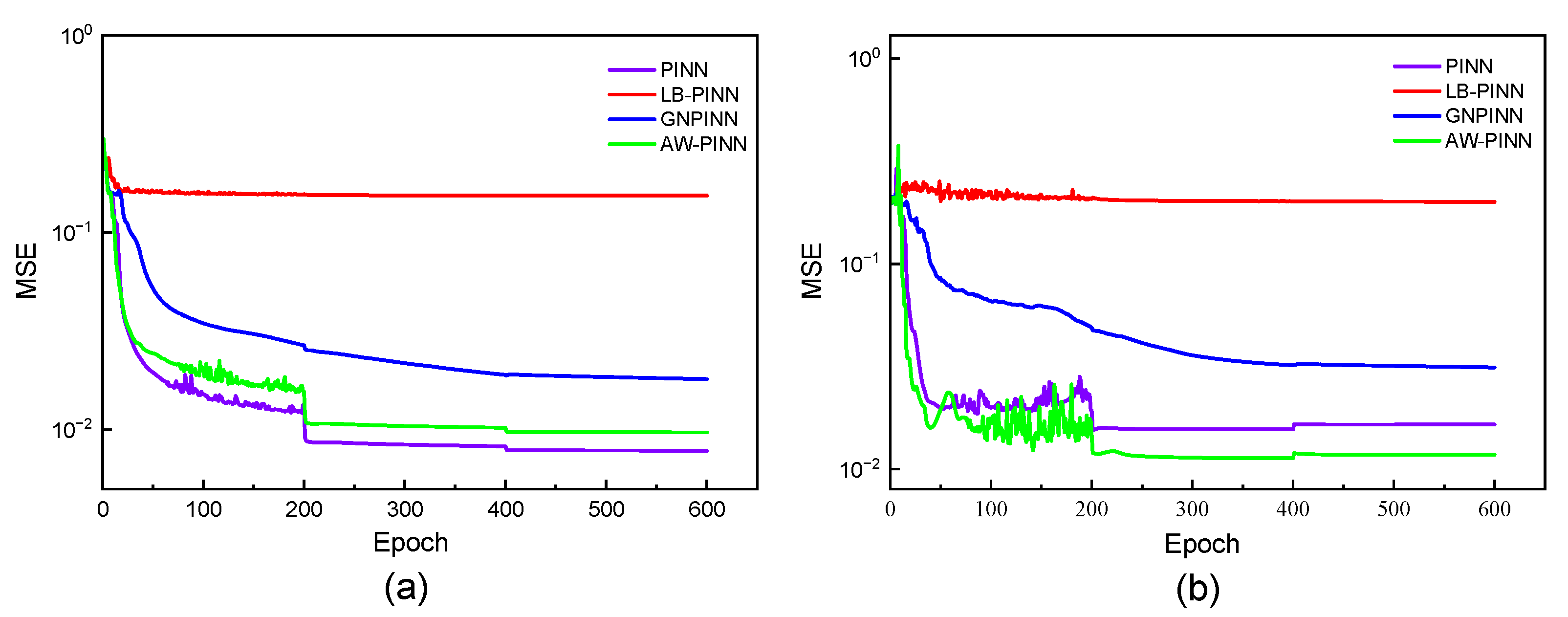

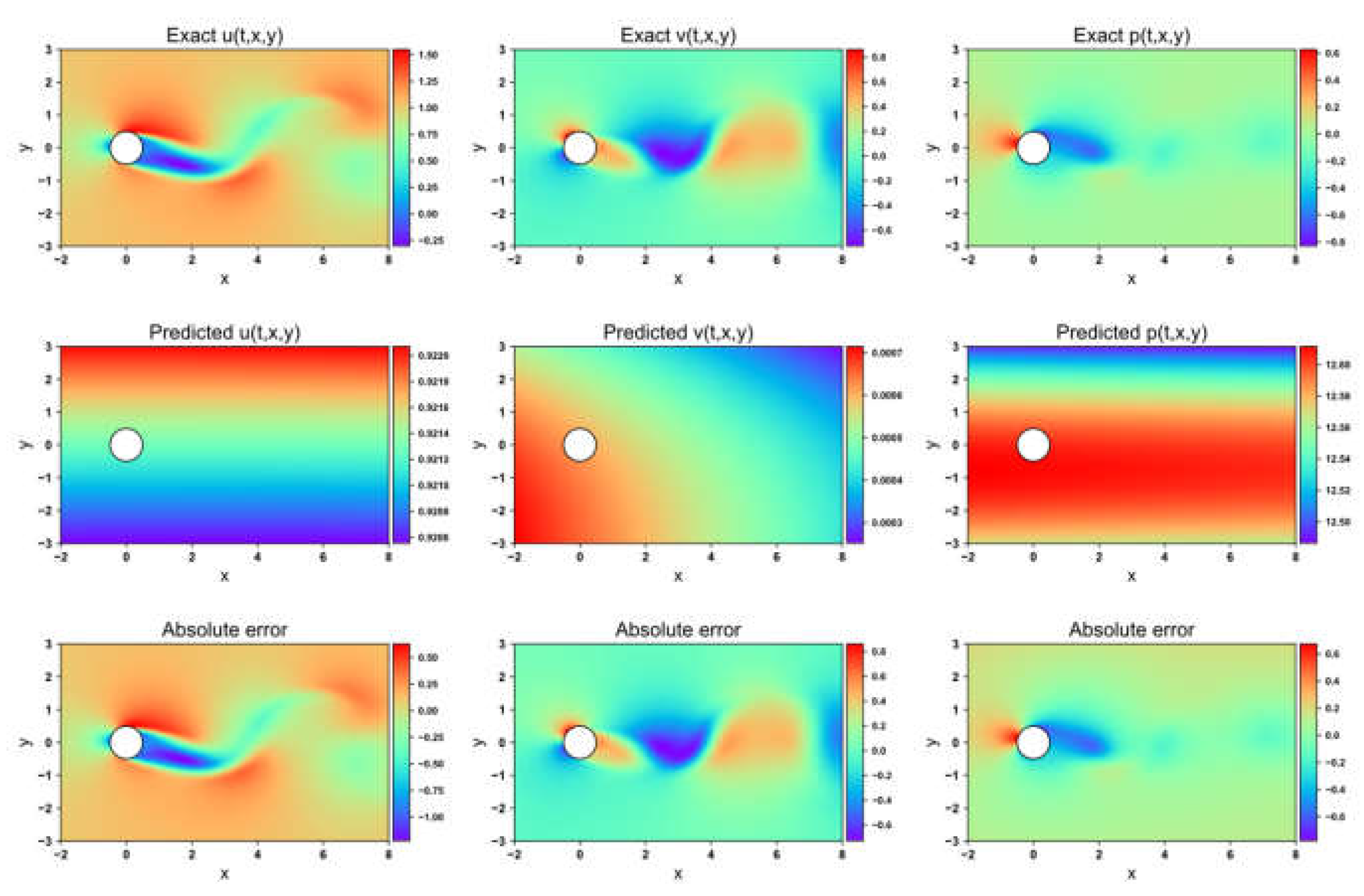

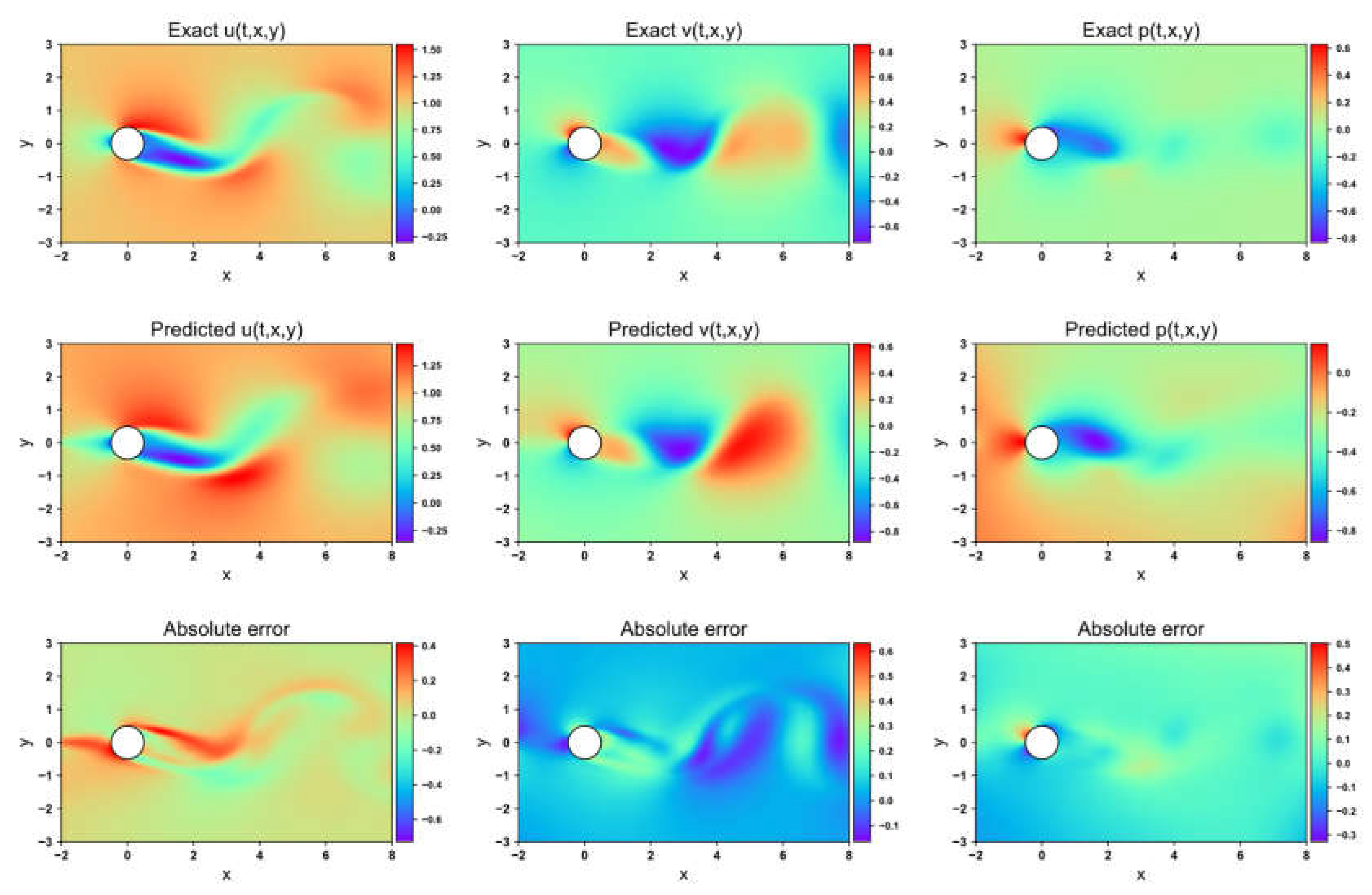

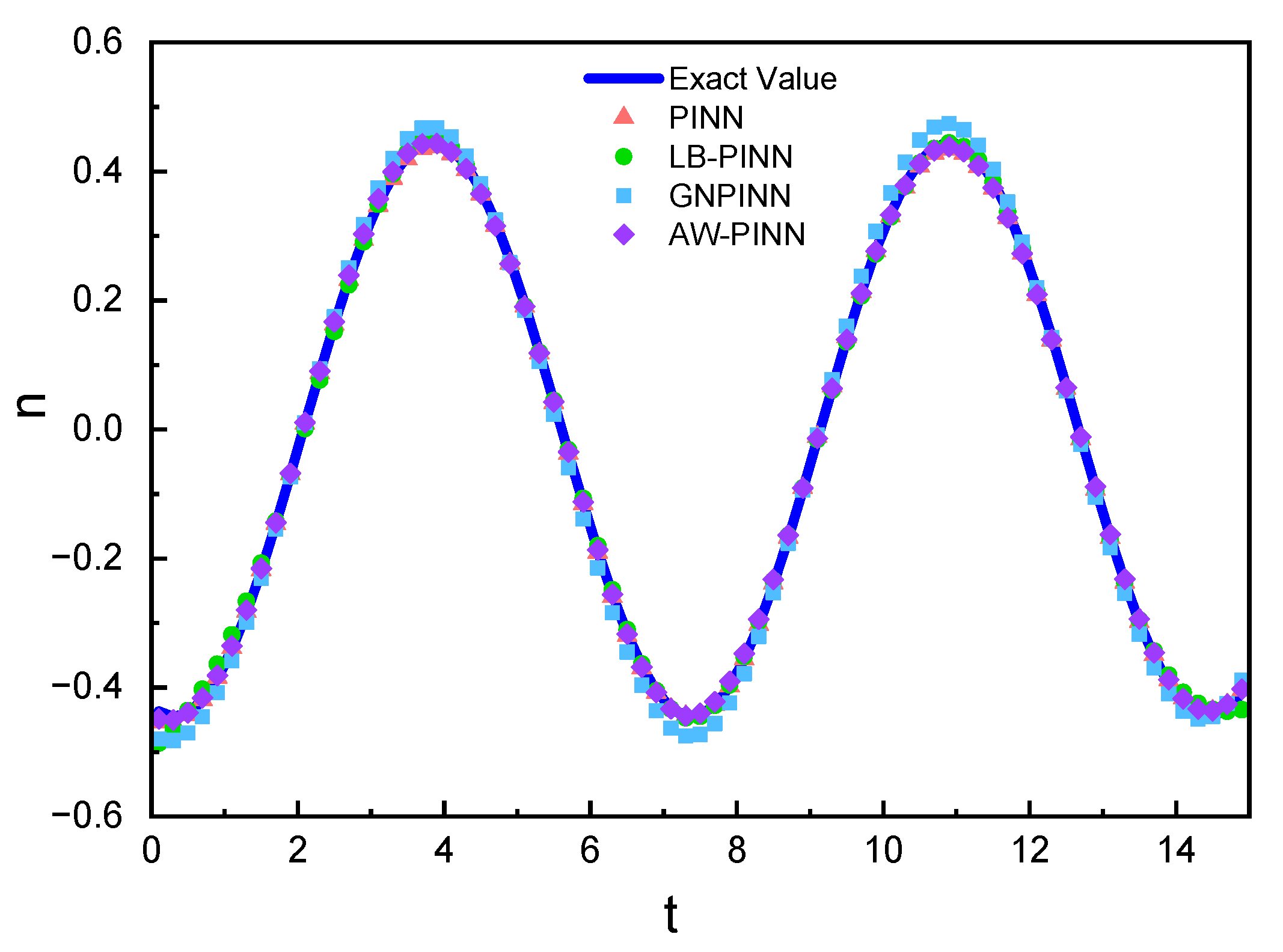

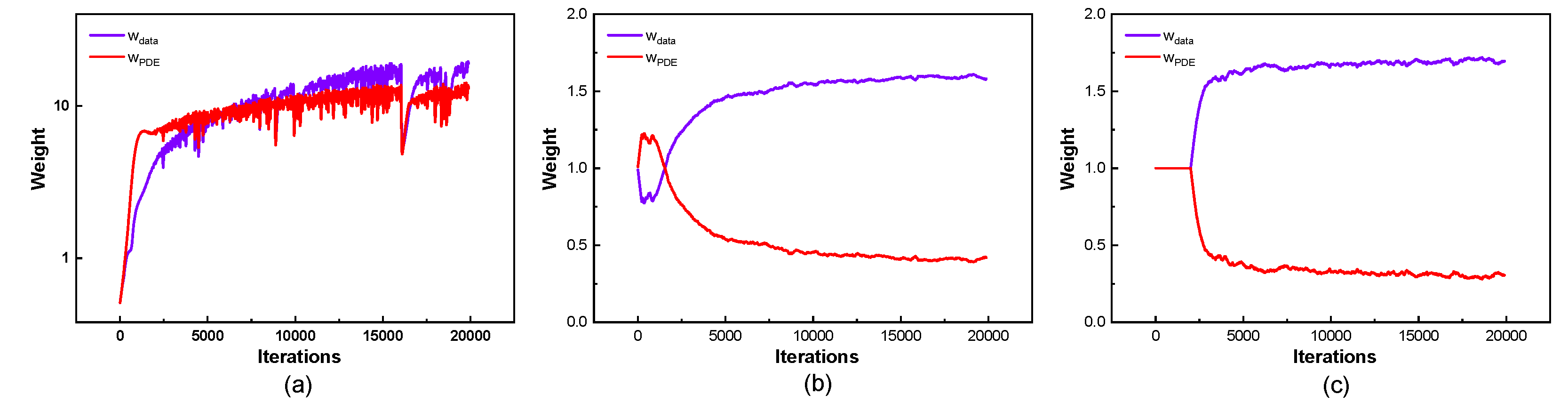

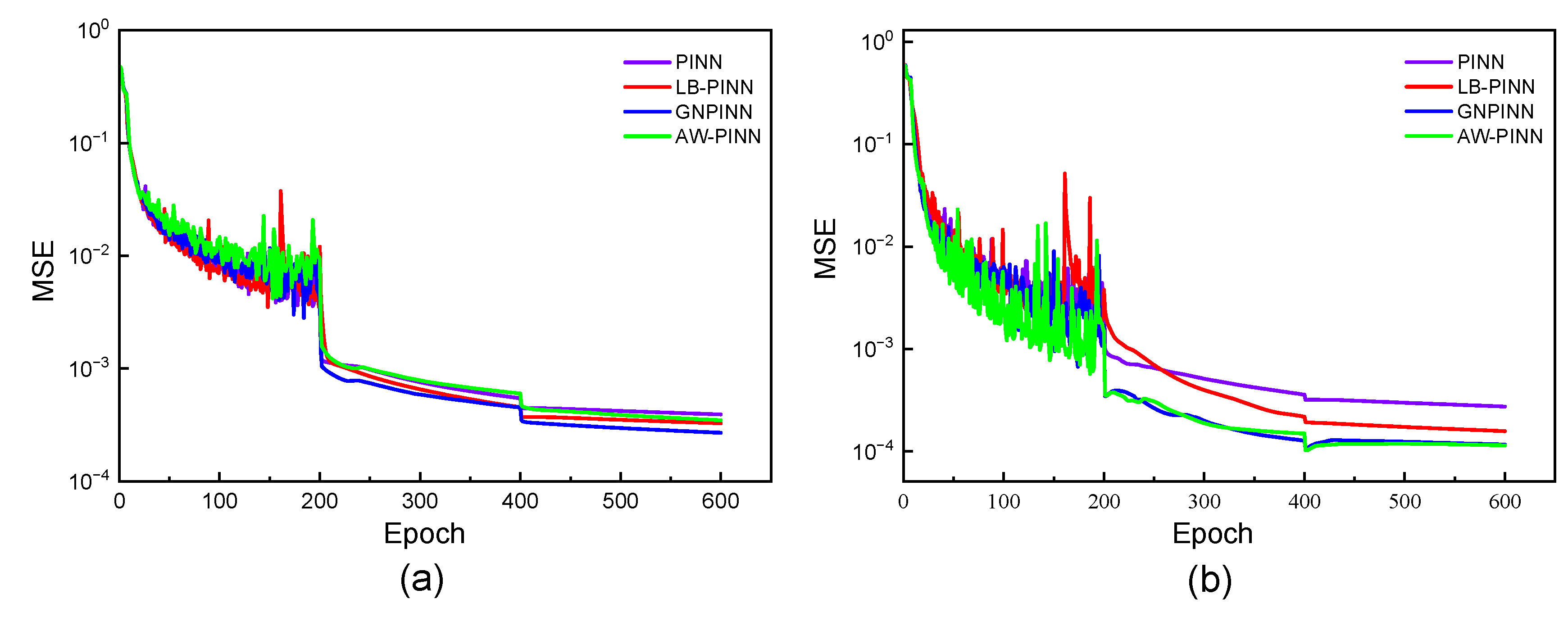

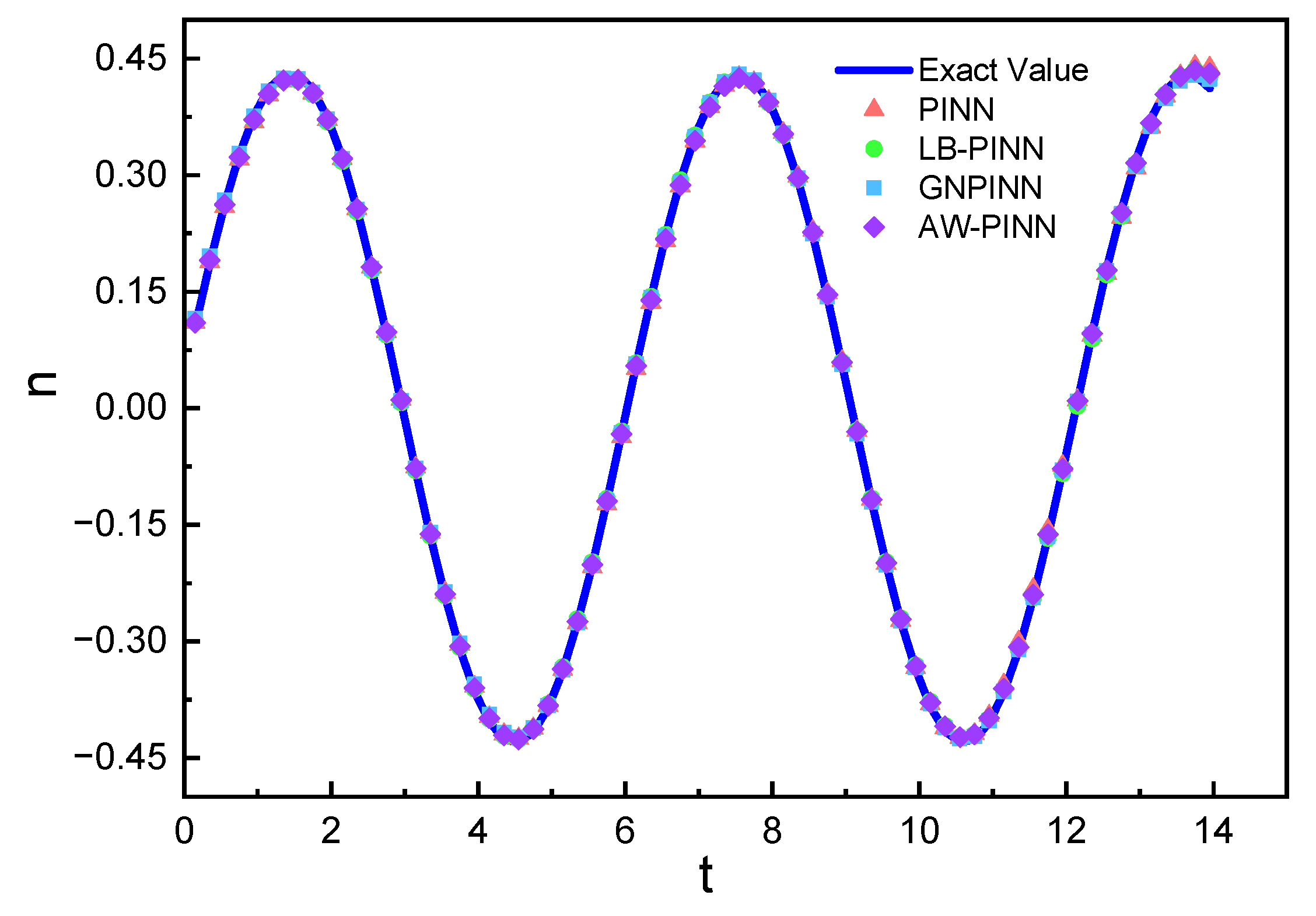

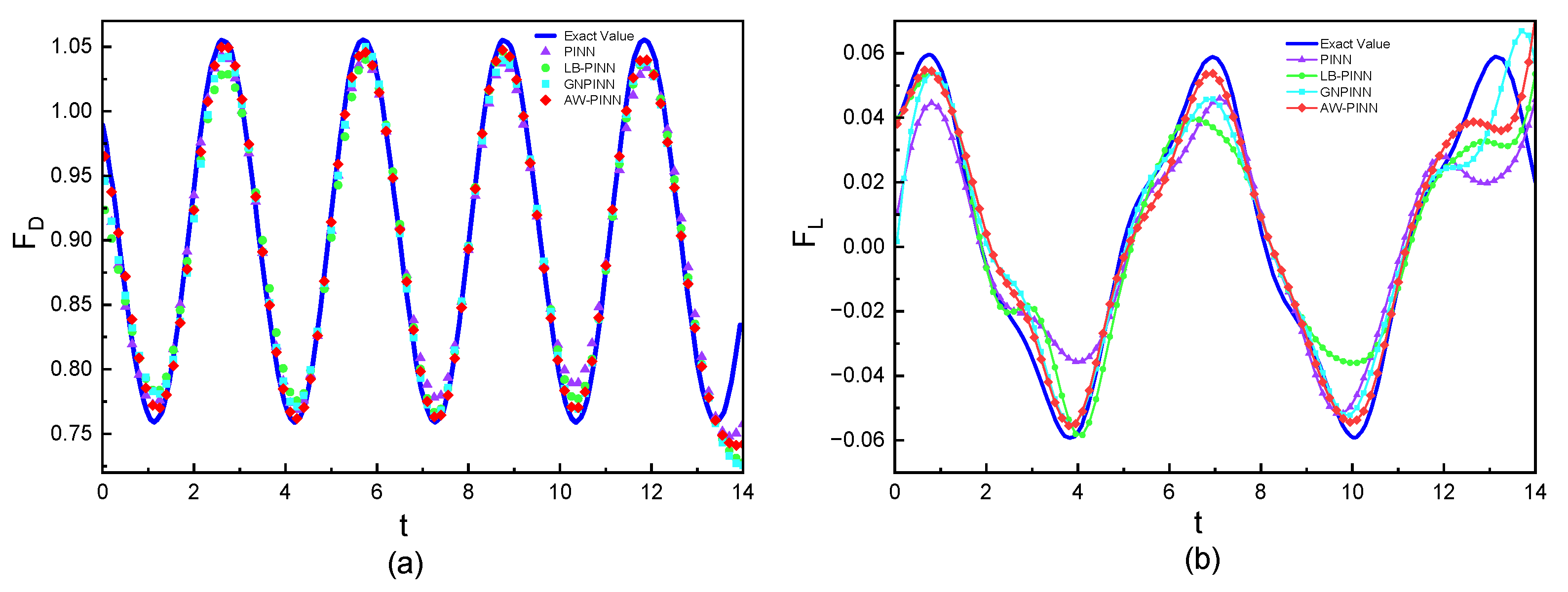

(2) When addressing the single-degree-of-freedom vortex-induced vibration problem, both LB-PINN and GNPINN demonstrate strong performance. GNPINN achieves a mean squared error that is half of the PINN model in predicting the flow field velocity and structural displacement, and reduces the flow field pressure prediction error to one-third, significantly improving model performance. Although LB-PINN also enhances model performance, the improvement in flow field velocity prediction accuracy is limited. However, in the case of the two-degree-of-freedom VIV problem, both models tend to prioritize equation loss during training, resulting in larger prediction errors compared to PINN and failing to effectively address the two-degree-of-freedom VIV problem.

(3) Among all the models, AW-PINN exhibits the best performance in the single-degree-of-freedom VIV problem, significantly improving prediction accuracy. Compared to the other two optimization models, AW-PINN shows better stability in the two-degree-of-freedom VIV problem, as it tends to prioritize training data loss, significantly improving the prediction precision of flow field velocity and structural displacement, while also enhancing the prediction precision of the flow field pressure.

Although AW-PINN demonstrates superior performance compared to PINN, there are still some challenges to address. For example, AW-PINN requires the calculation of the loss gradient with respect to the network's shared layers, which increases the computational resources needed for training. Therefore, applying the network to large datasets and complex models using GPU parallel technology remains a challenge. Additionally, in practical applications, network models must balance multiple loss terms, necessitating further verification of the model’s performance and stability when managing multiple loss terms.

Figure 1.

Physical model of two-degree-of freedom (2-DOF) vortex-induced vibration

Figure 1.

Physical model of two-degree-of freedom (2-DOF) vortex-induced vibration

Figure 2.

Network architecture of PINN for solving vortex induced vibration problems

Figure 2.

Network architecture of PINN for solving vortex induced vibration problems

Figure 3.

Network architecture of AW-PINN for solving vortex-induced vibration problem

Figure 3.

Network architecture of AW-PINN for solving vortex-induced vibration problem

Figure 4.

Computational domain and boundary conditions of the flow field

Figure 4.

Computational domain and boundary conditions of the flow field

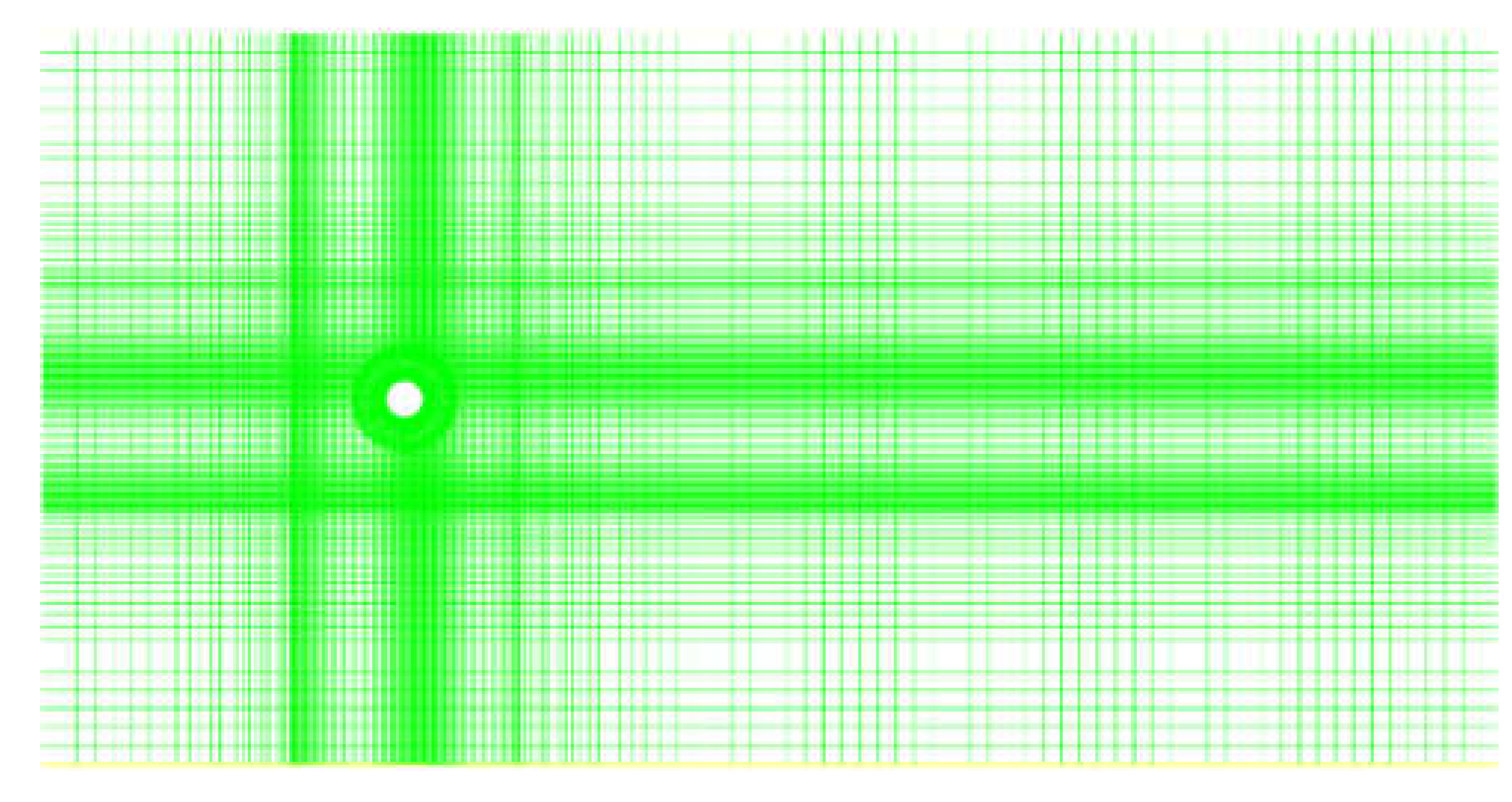

Figure 5.

Meshing for computational domains

Figure 5.

Meshing for computational domains

Figure 6.

Adaptive weight changes in the 2-DOF cylinder:(a) LB-PINN; (b) GNPINN; (c) AW-PINN

Figure 6.

Adaptive weight changes in the 2-DOF cylinder:(a) LB-PINN; (b) GNPINN; (c) AW-PINN

Figure 7.

Mean square error of four models in the 2-DOF cylinder:(a) Training loss curves; (b) Test error curves

Figure 7.

Mean square error of four models in the 2-DOF cylinder:(a) Training loss curves; (b) Test error curves

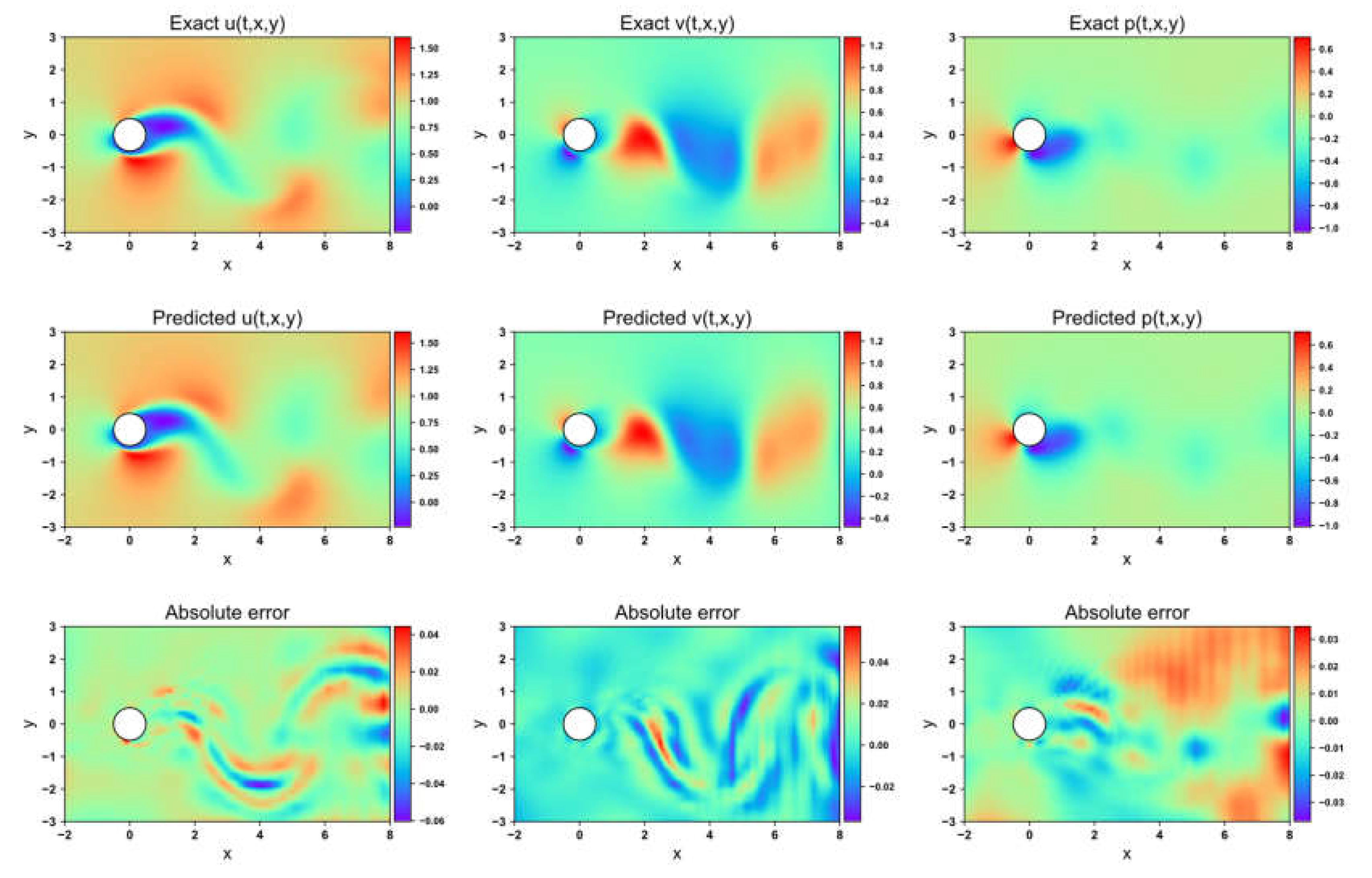

Figure 8.

Flow field prediction for PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 8.

Flow field prediction for PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

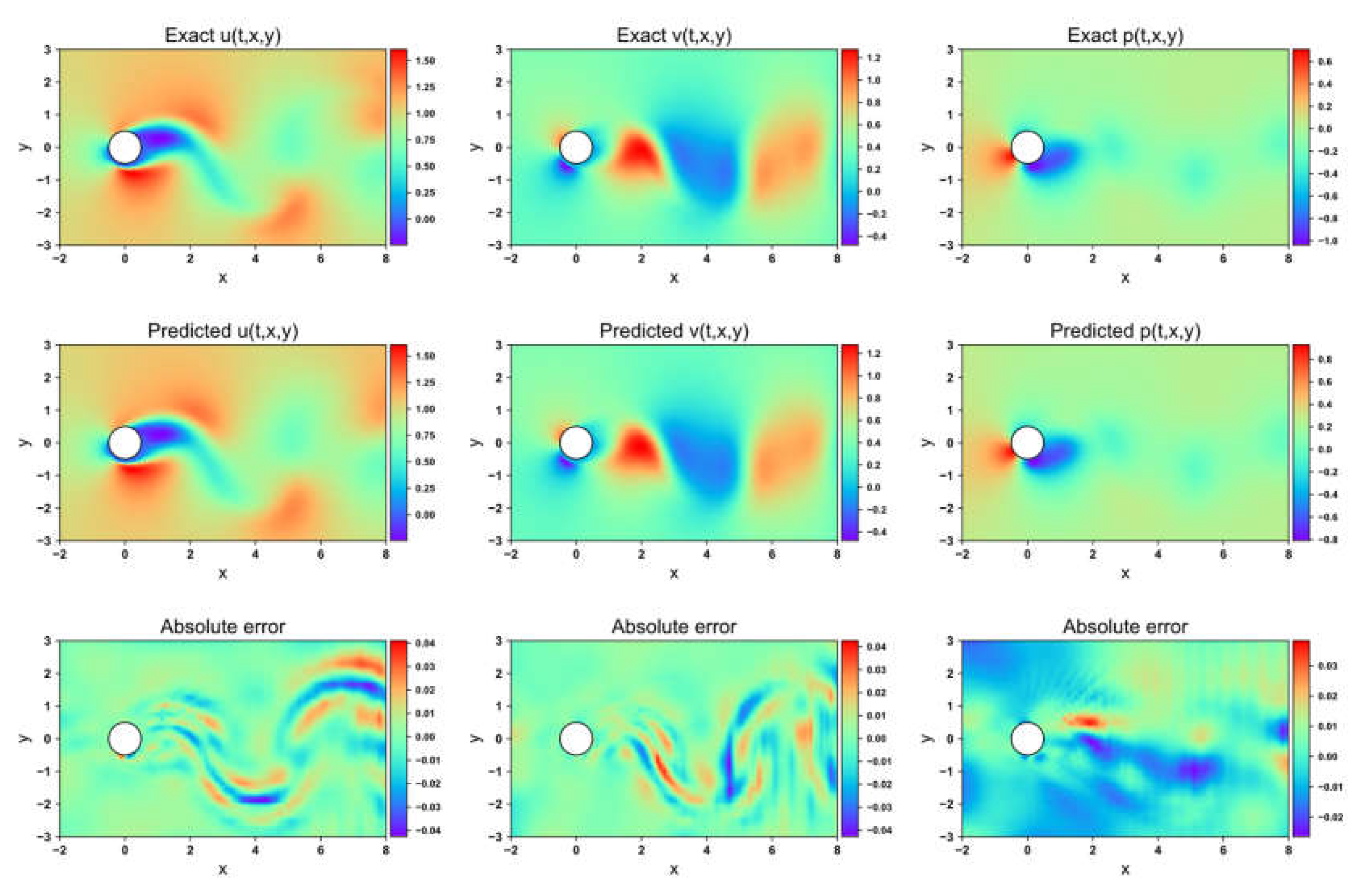

Figure 9.

Flow field prediction for LB-PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 9.

Flow field prediction for LB-PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

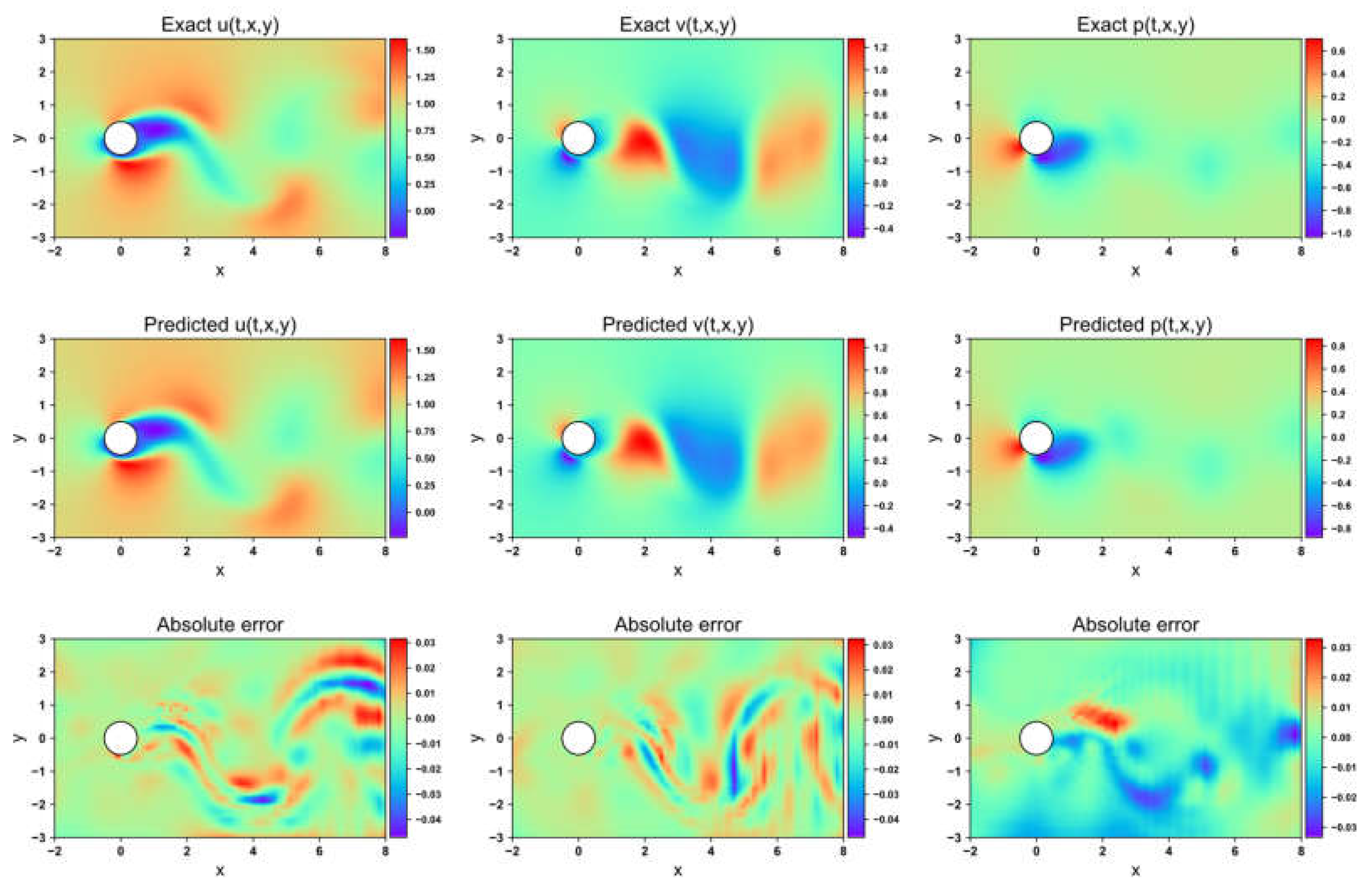

Figure 10.

Flow field prediction for GNPINN in 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 10.

Flow field prediction for GNPINN in 2-DOF cylinder

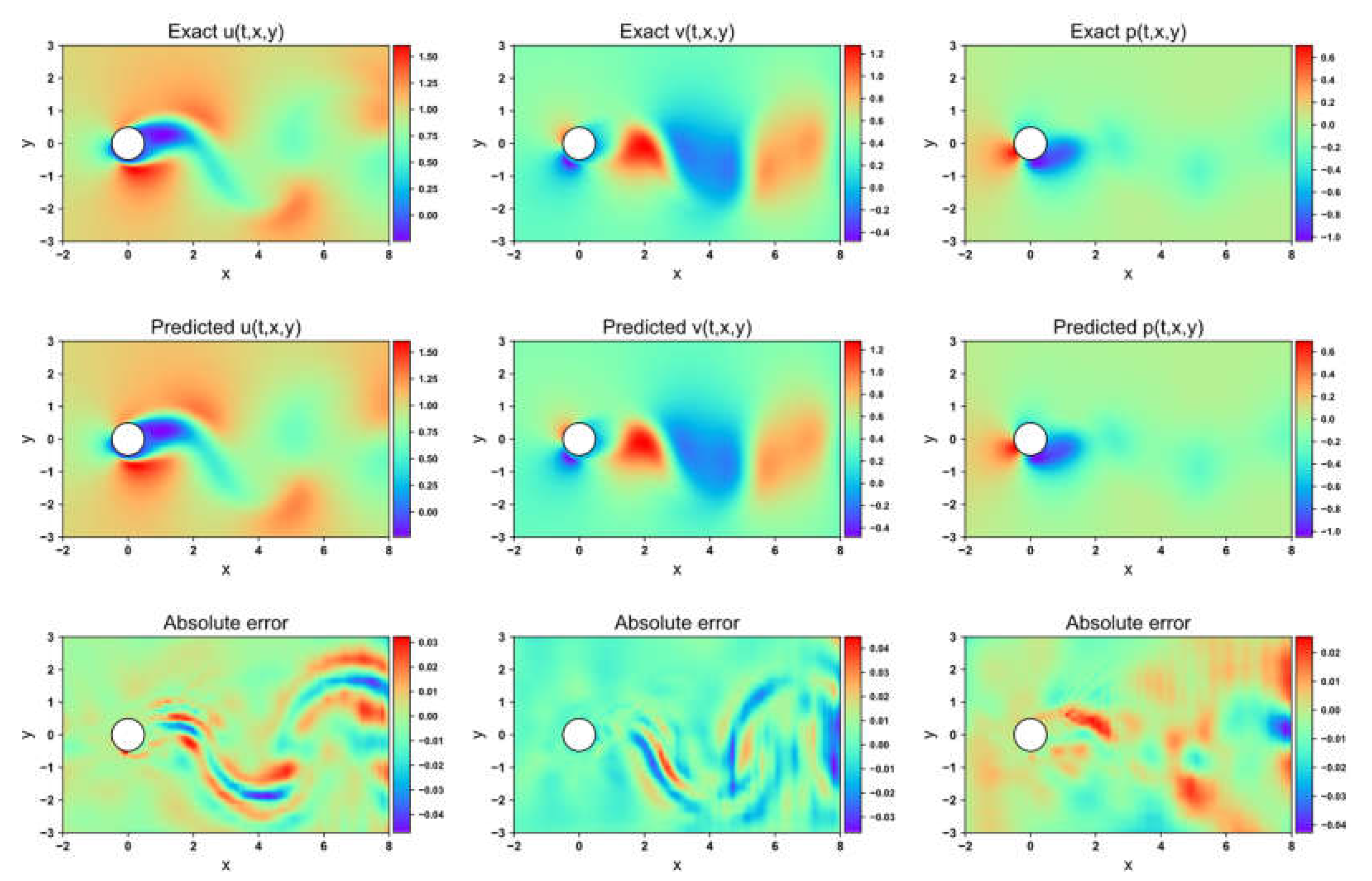

Figure 11.

Flow field prediction for AW-PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 11.

Flow field prediction for AW-PINN in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 12.

Transverse structural displacement prediction in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 12.

Transverse structural displacement prediction in the 2-DOF cylinder

Figure 13.

Adaptive weight changes in the 1-DOF cylinder: (a) LB-PINN;(b) GNPINN;(c) AW-PINN

Figure 13.

Adaptive weight changes in the 1-DOF cylinder: (a) LB-PINN;(b) GNPINN;(c) AW-PINN

Figure 14.

Mean square error of four models in the 1-DOF cylinder:(a) training loss curves;(b) test error curves

Figure 14.

Mean square error of four models in the 1-DOF cylinder:(a) training loss curves;(b) test error curves

Figure 15.

Flow field prediction for PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 15.

Flow field prediction for PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 16.

Flow field prediction for LB-PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 16.

Flow field prediction for LB-PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 17.

Flow field prediction for GNPINN in 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 17.

Flow field prediction for GNPINN in 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 18.

Flow field prediction for AW-PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 18.

Flow field prediction for AW-PINN in the 1-DOF cylinder

Figure 19.

Transverse structural displacement prediction in the 1-DOF cylinder.

Figure 19.

Transverse structural displacement prediction in the 1-DOF cylinder.

Figure 20.

Force prediction of cylinder:(a) drag of cylinder(b) lift of cylinder

Figure 20.

Force prediction of cylinder:(a) drag of cylinder(b) lift of cylinder

Table 1.

Comparison of numerical simulation results with other studies

Table 1.

Comparison of numerical simulation results with other studies

| Numerical result |

|

|

|

|

| Bao et al. |

0.030 |

0.61 |

0.29 |

2.03 |

| This study |

0.031 |

0.60 |

0.27 |

2.08 |

Table 2.

Overview of different models

Table 2.

Overview of different models

| Model |

Brief description of the model |

| PINN |

The baseline PINN trained with an equal weight loss function.[34] |

| LB-PINN |

The loss function is optimized using uncertainty to enhance PINN performance.[43] |

| GNPINN |

Loss weights are adjusted based on gradient normalization to optimize PINN.[44] |

| AW-PINN |

The PINN optimization method proposed in this study. |

Table 3.

Mean squared errors of predictions by different models

Table 3.

Mean squared errors of predictions by different models

| Model |

Mean Squared Error |

| u |

v |

p |

n |

r |

| PINN |

3.53×10-3 |

5.14×10-3 |

6.55×10-3 |

1.02×10-3 |

2.79×10-4 |

| LB-PINN |

1.05×10-1 |

5.17×10-2 |

4.23×10-2 |

4.58×10-5 |

1.02×10-3 |

| GNPINN |

1.04×10-2 |

1.12×10-2 |

7.09×10-3 |

1.86×10-3 |

7.39×10-4 |

| AW-PINN |

2.30×10-3 |

3.29×10-3 |

5.47×10-3 |

5.69×10-4 |

1.46×10-4 |

Table 4.

Mean squared error using the validation dataset

Table 4.

Mean squared error using the validation dataset

| Model |

Mean Squared Error |

| u |

v |

p |

n |

| PINN |

5.58×10-5 |

5.64×10-5 |

1.35×10-4 |

2.65×10-5 |

| LB-PINN |

4.26×10-5 |

4.14×10-5 |

5.66×10-5 |

1.70×10-5 |

| GNPINN |

3.25×10-5 |

3.00×10-5 |

4.14×10-5 |

1.24×10-5 |

| AW-PINN |

3.09×10-5 |

2.96×10-5 |

4.25×10-5 |

1.14×10-5 |