Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

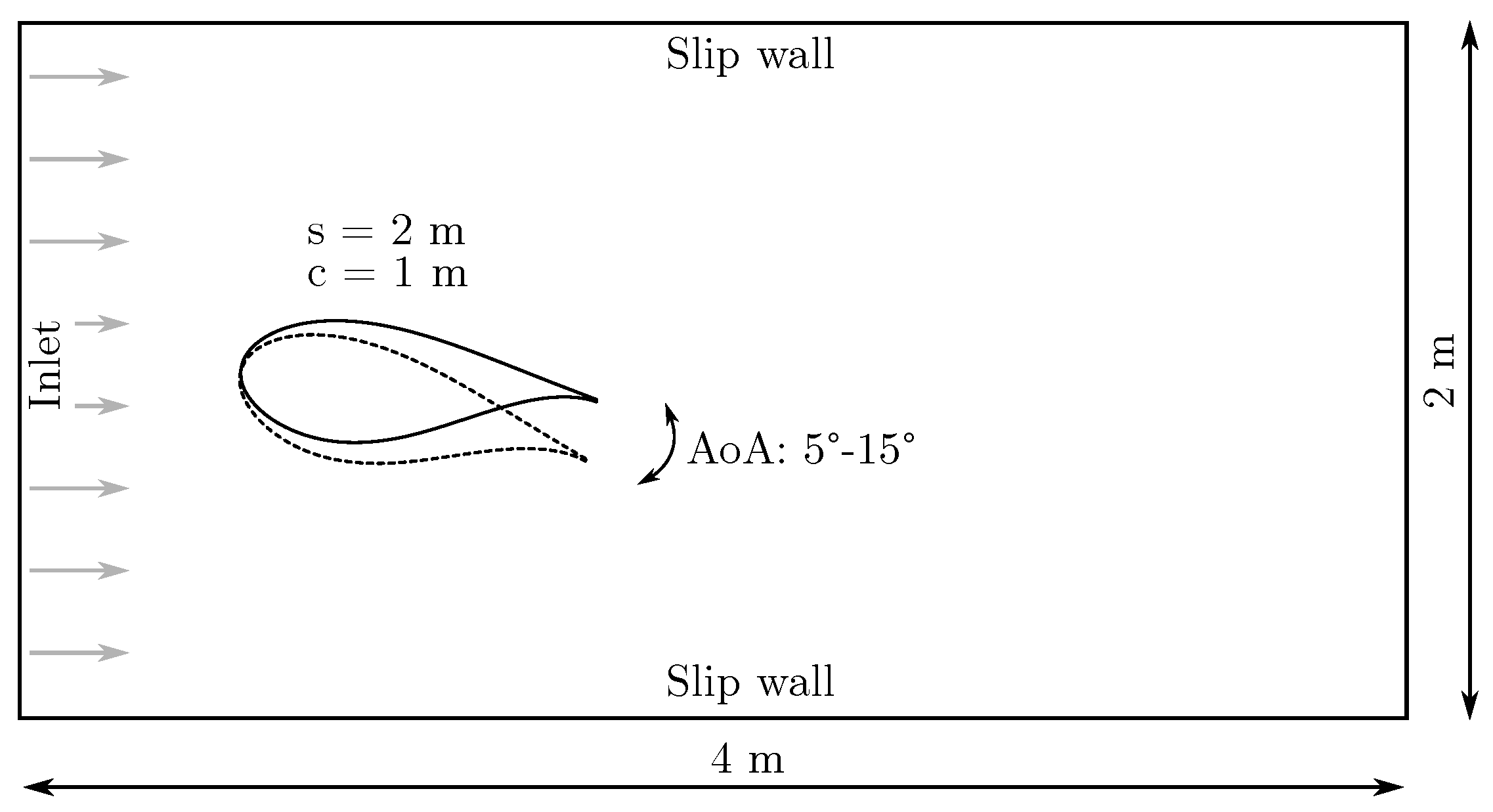

2.1. Variable Geometry Problem Definition

2.2. Governing Euations

2.3. PINN-Based Surrogate Method

2.4. Reference Data

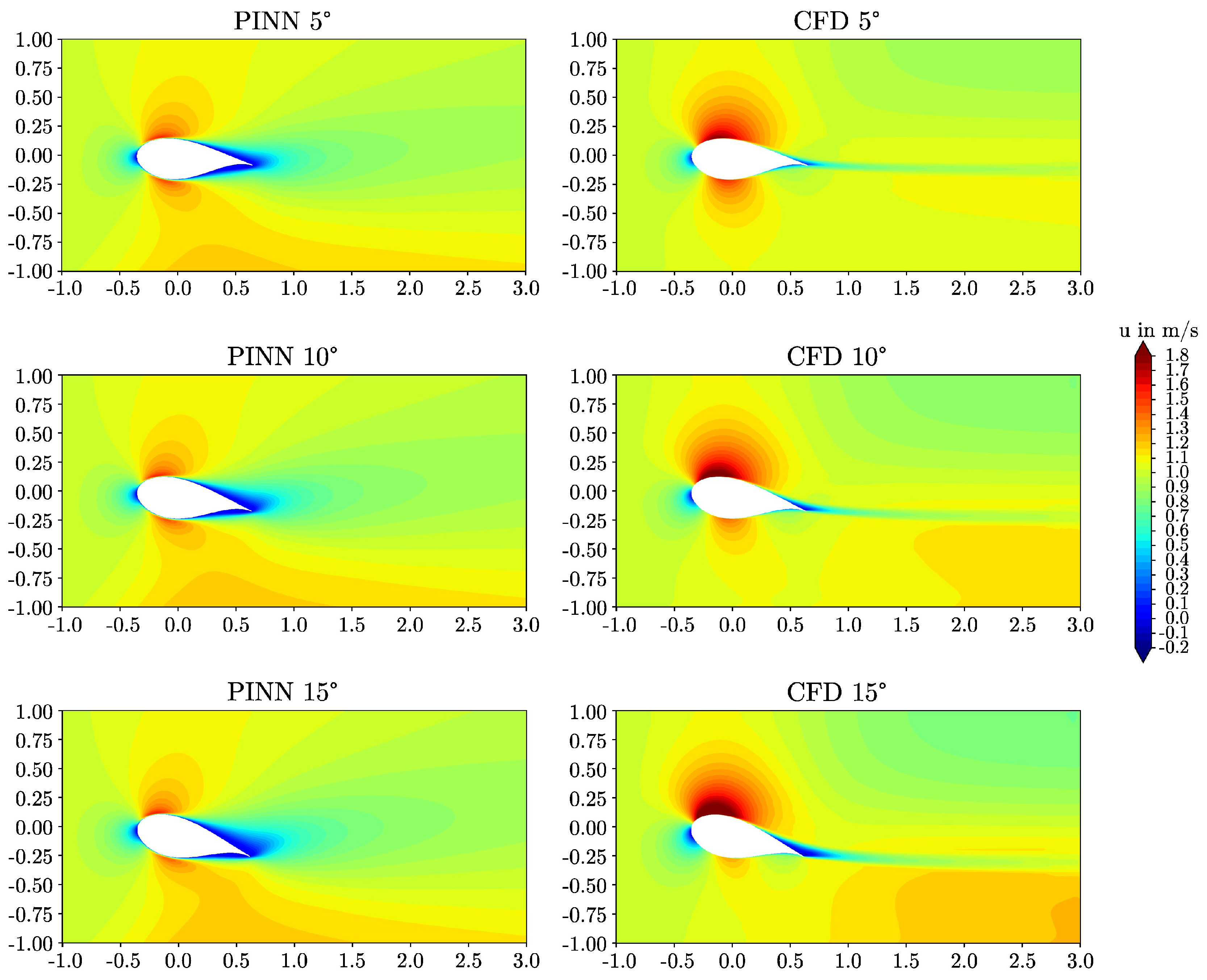

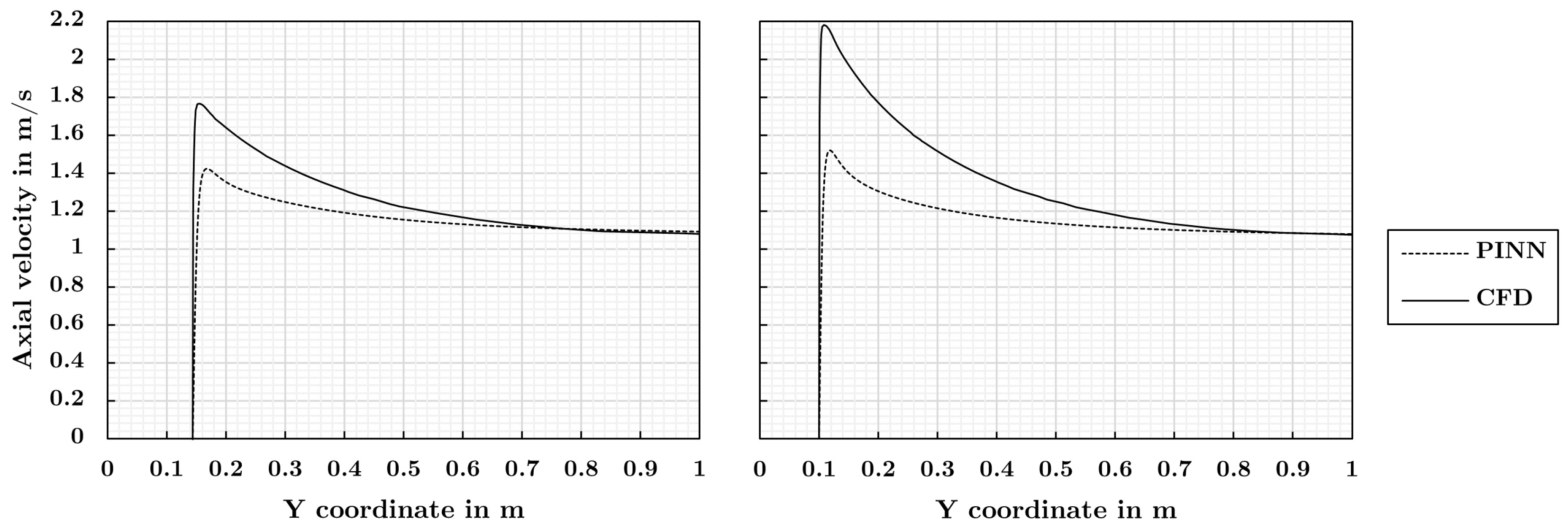

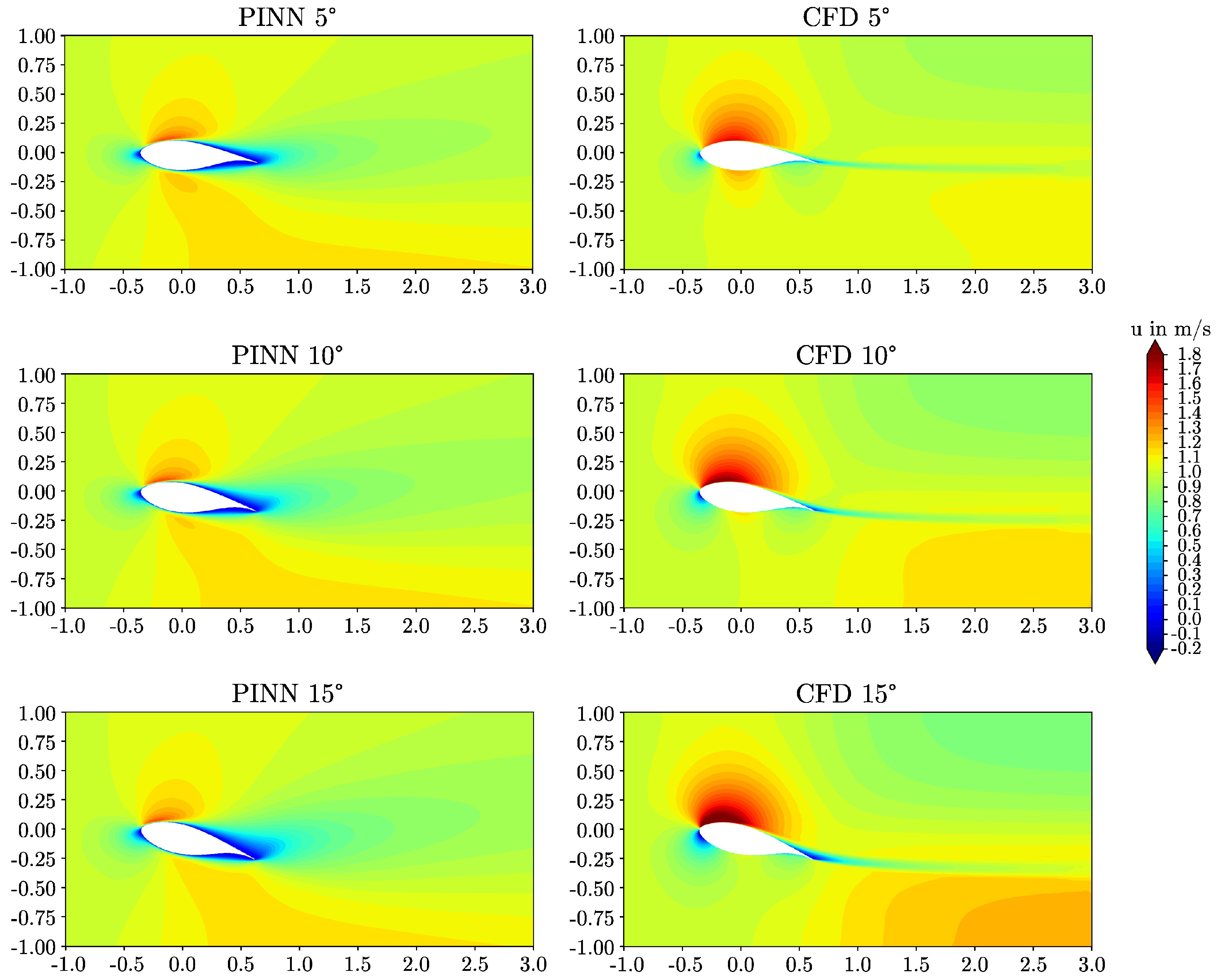

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Summary and Conclusions

- Using the investigated method, it was possible to train a single network to learn the family of flow fields corresponding to variable angles of attack between 5° and 15° without generation of a computational grid. This is a substantial advantage over traditional solvers that could only by used to calculate a single solution field for a single angle of attack at a time. After successful improvement of the method, this trait would make physics-informed deep learning a powerful tool for surrogate modeling.

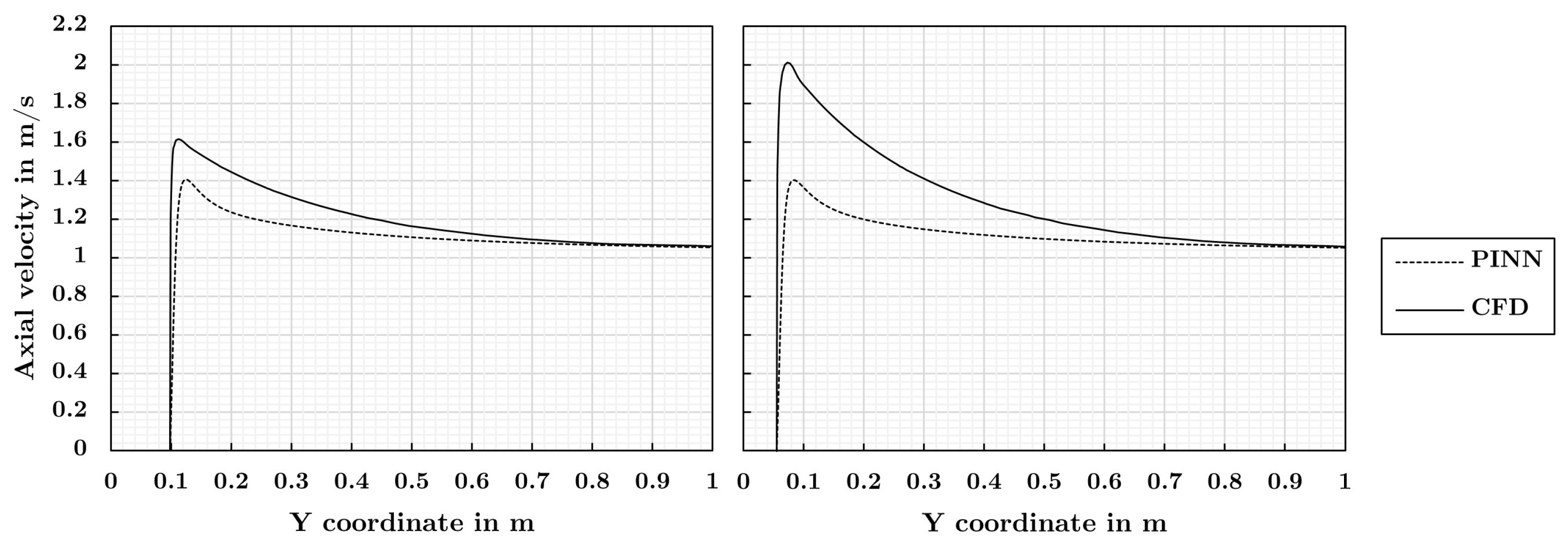

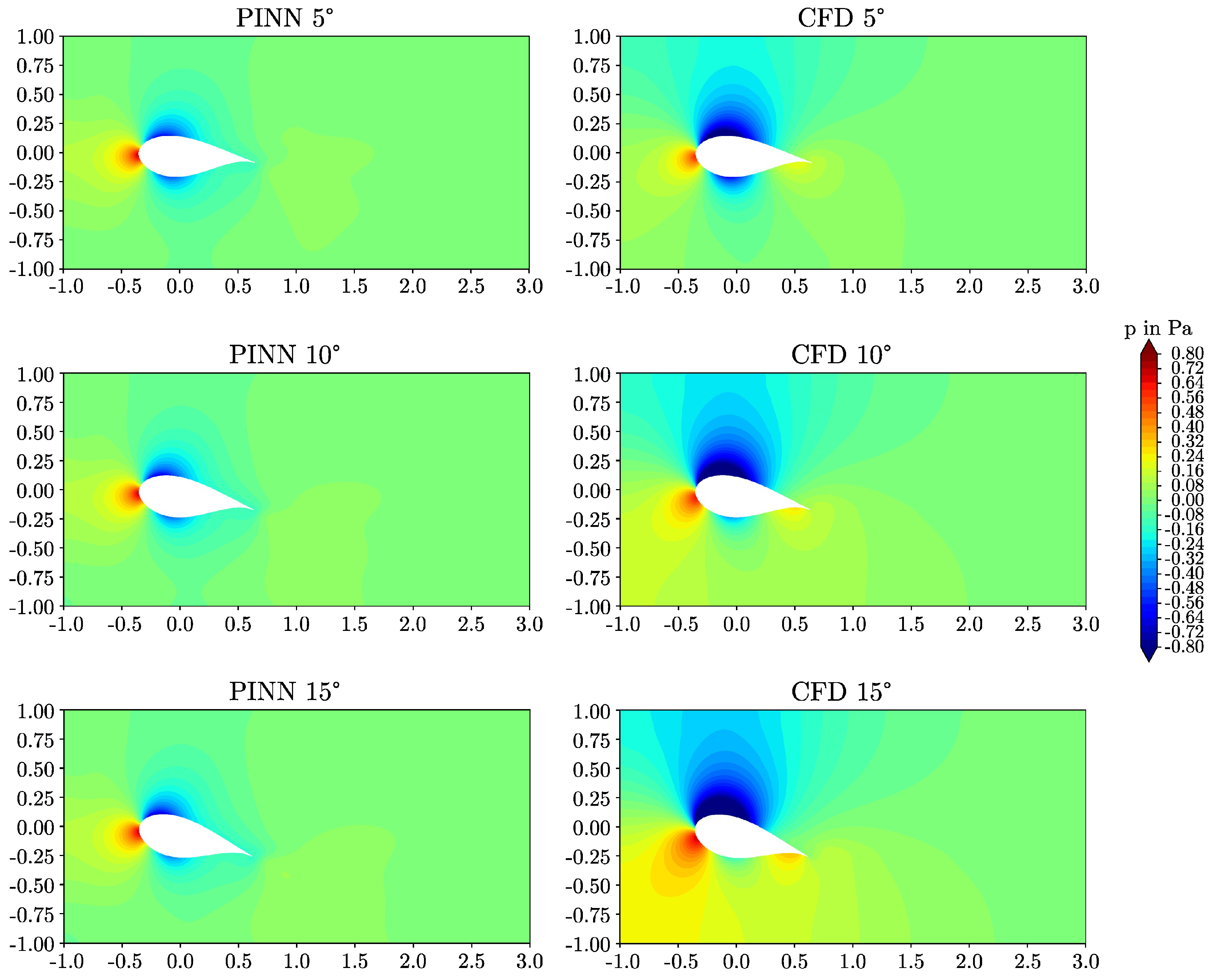

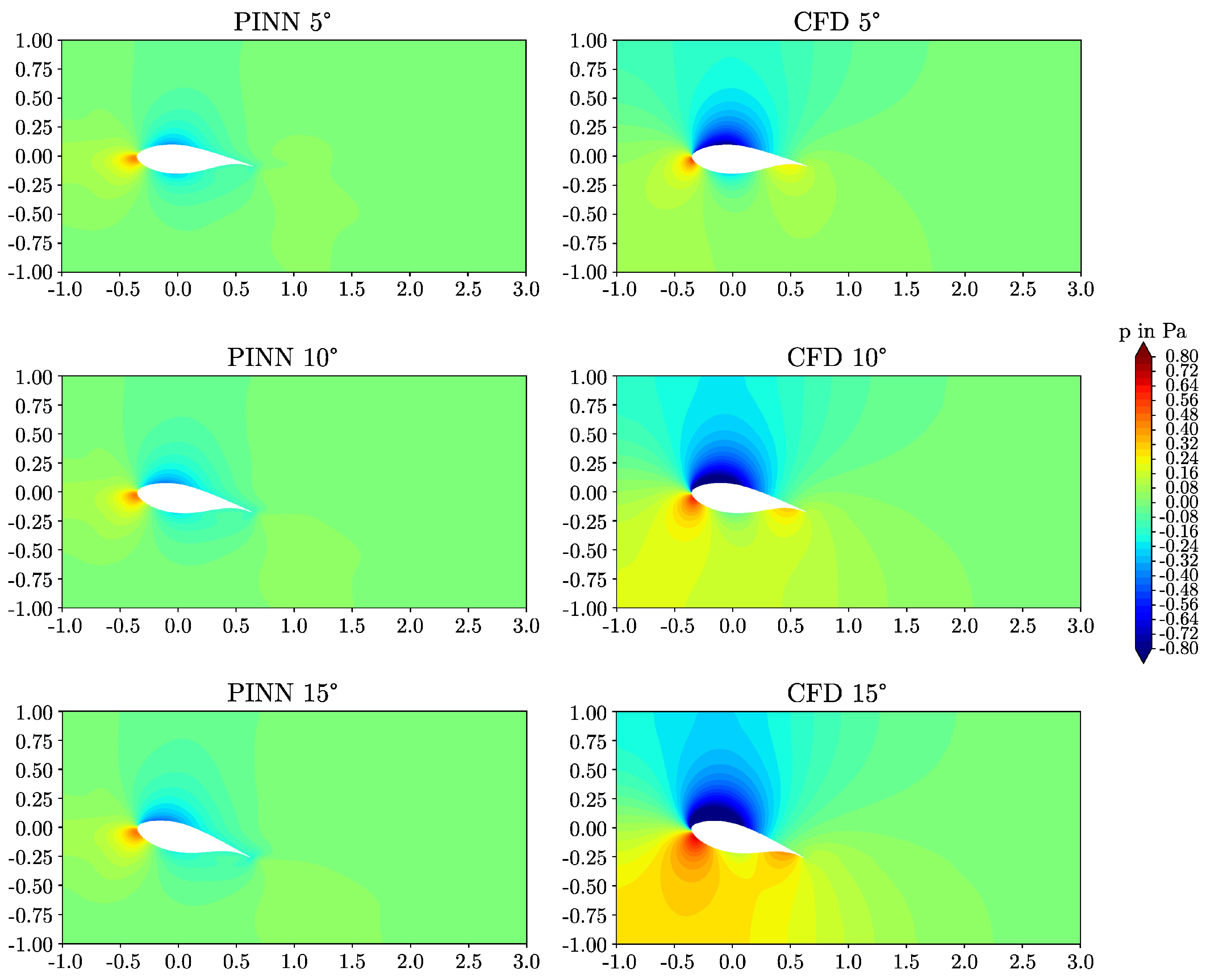

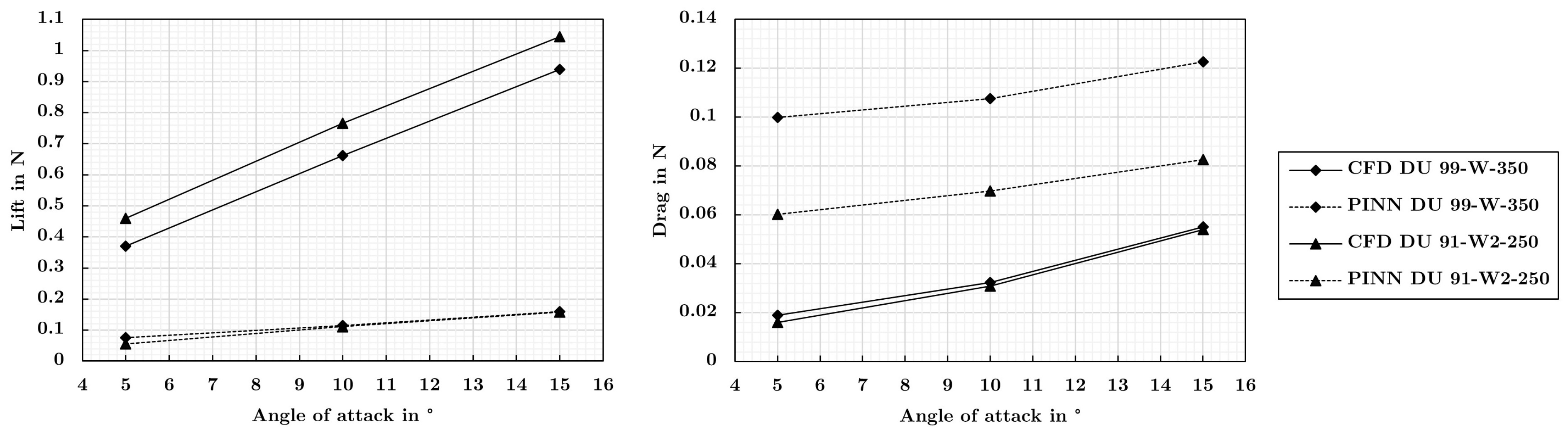

- The models captured qualitative features of the high Reynolds number flow fields such as high gradient boundary layers, stagnation regions, and wakes. Furthermore, the models recognized lift and drag values increasing with the angle of attack and the higher drag of the thicker airfoil. It is remarkable that all of these features were predicted without incorporating labeled reference data into the training routine.

- However, compared to the reference simulations, the extremes of the velocity and pressure fields were underestimated and the thicknesses of the shear layers were overestimated by the PINNs. Consequently, the lift was underestimated and the drag was overestimated for both airfoils. With the observed performance, PINNs can not currently compete with traditional computations in terms of accuracy. The difficulty of the deep learning problem and the resulting limited accuracy of the predictions is a consequence of the elevated Reynolds number of the problem. More work is necessary to further develop the PINN-based surrogate method.

- Future studies should focus on successfully implementing two equation turbulence models and reducing the training error by applying more advanced training methods. The present study is aimed to outline the potential capabilities of simultaneous unsupervised physics-informed deep learning and to encourage further research and methodological developments of the technique under application to high Reynolds number flows.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- E. H. W. Ang, G. Wang, and B. F. Ng. Physics-informed neural networks for low reynolds number flows over cylinder. Energies, 16(12), 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Arthurs and A. P. King. Active training of physics-informed neural networks to aggregate and interpolate parametric solutions to the navier-stokes equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 438:None, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Rao, H. Sun, and Y. Liu. Physics-informed deep learning for incompressible laminar flows. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters, 10(3):207–212, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Dwivedi, N. Parashar, and B. Srinivasan. Distributed physics informed neural network for data-efficient solution to partial differential equations, 2019. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.08967v1.

- H. Eivazi, M. Tahani, P. Schlatter, and R. Vinuesa. Physics-informed neural networks for solving reynolds-averaged navier–stokes equations. Physics of Fluids, 34(7):075117, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Fernández-Delgado, M. S. Sirsat, E. Cernadas, S. Alawadi, S. Barro, and M. Febrero-Bande. An extensive experimental survey of regression methods. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society, 111:11–34, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghosh, A. Chakraborty, G. O. Brikis, and B. Dey. Rans-pinn based simulation surrogates for predicting turbulent flows. 2023. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.06034.pdf.

- J. H. Harmening, F.-J. Peitzmann, and O. el Moctar. Effect of network architecture on physics-informed deep learning of the reynolds-averaged turbulent flow field around cylinders without training data. Frontiers in Physics, 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Harmening, F. Pioch, and D. Schramm. Physics informed neural networks as multidimensional surrogate models of cfd simulations. In Machine Learning und Artificial Intelligence in Strömungsmechanik und Strukturanalyse, Wiesbaden, Germany, 16.–17. may, pages 71–80. NAFEMS, may 2022.

- O. Hennigh, S. Narasimhan, M. A. Nabian, A. Subramaniam, K. Tangsali, Z. Fang, M. Rietmann, W. Byeon, and S. Choudhry. Nvidia simnet™: An ai-accelerated multi-physics simulation framework. In M. Paszynski, D. Kranzlmüller, V. V. Krzhizhanovskaya, J. J. Dongarra, and P. M. Sloot, editors, Computational Science – ICCS 2021, volume 12746 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 447–461. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021.

- W. Huang, X. Zhang, W. Zhou, and Y. Liu. Learning time-averaged turbulent flow field of jet in crossflow from limited observations using physics-informed neural networks. Physics of Fluids, 35(2), 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Harmening, F. Pioch, L. Fuhrig, F.-J. Peitzmann, D. Schramm, and O. el Moctar. Data-assisted training of a physics-informed neural network to predict the reynolds-averaged turbulent flow field around a stalled airfoil under variable angles of attack. 2023. Preprint at https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202304.1244/v1.

- X. Jin, S. Cai, H. Li, and G. E. Karniadakis. Nsfnets (navier-stokes flow nets): Physics-informed neural networks for the incompressible navier-stokes equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 426:109951, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Jonkman, S. Butterfield, W. Musial, and G. Scott. Definition of a 5-mw reference wind turbine for offshore system development, 2009.

- V. Kag, K. Seshasayanan, and V. Gopinath. Physics-informed data based neural networks for two-dimensional turbulence. Physics of Fluids, 34(5), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, Y. Choi, D. Widemann, and T. Zohdi. A fast and accurate physics-informed neural network reduced order model with shallow masked autoencoder. Journal of Computational Physics, 451:110841, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Krishnapriyan, A. Gholami, S. Zhe, R. Kirby, and M. W. Mahoney. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. In M. Ranzato, A. Beygelzimer, Y. Dauphin, P.S. Liang, and J. Wortman Vaughan, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 34, pages 26548–26560. Curran Associates, Inc, 2021.

- I. E. Lagaris, A. Likas, and D. I. Fotiadis. Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial differential equations. IEEE transactions on neural networks, 9(5):987–1000, 1998. [CrossRef]

- R. Laubscher and P. Rousseau. Application of a mixed variable physics-informed neural network to solve the incompressible steady-state and transient mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations for flow over in-line heated tubes. Applied Soft Computing, 114:108050, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Lu, X. Meng, Z. Mao, and G. E. Karniadakis. Deepxde: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Review, 63(1):208–228, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Ma, Y. Zhang, N. Thuerey, X. H. null, and O. J. Haidn. Physics-driven learning of the steady navier-stokes equations using deep convolutional neural networks. Communications in Computational Physics, 32(3):715–736, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Patel, V. Mons, O. Marquet, and G. Rigas. Turbulence model augmented physics informed neural networks for mean flow reconstruction, 2023. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.01065v1.

- F. Pioch, J. H. Harmening, A. M. Müller, F.-J. Peitzmann, D. Schramm, and O. el Moctar. Turbulence modeling for physics-informed neural networks: Comparison of different rans models for the backward-facing step flow. Fluids, 8(2):43, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Raissi, P. Perdikaris, and G. E. Karniadakis. Physics informed deep learning (part i): Data-driven solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations, 2017. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.10561v1.

- M. Raissi, P. Perdikaris, and G. E. Karniadakis. Physics informed deep learning (part ii): Data-driven discovery of nonlinear partial differential equations, 2017. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.10566v1.

- M. Raissi, P. Perdikaris, and G. E. Karniadakis. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 378:686–707, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Raissi, A. Yazdani, and G. E. Karniadakis. Hidden fluid mechanics: Learning velocity and pressure fields from flow visualizations. Science (New York, N.Y.), 367(6481):1026–1030, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, H. Gao, S. Pan, and J.-X. Wang. Surrogate modeling for fluid flows based on physics-constrained deep learning without simulation data. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 361:112732, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, U. Sengupta, and M. Juniper. Physics-informed deep learning for simultaneous surrogate modeling and pde-constrained optimization of an airfoil geometry. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 411:116042, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Wandel, M. Weinmann, and R. Klein. Teaching the incompressible navier-stokes equations to fast neural surrogate models in 3d. Physics of Fluids, 33(4):047117, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, Y. Liu, and S. Wang. Dense velocity reconstruction from particle image velocimetry/particle tracking velocimetry using a physics-informed neural network. Physics of Fluids, 34(1):017116, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, K. Kashinath, M. Mustafa, A. Albert, and R. Yu. Towards physics-informed deep learning for turbulent flow prediction. In R. Gupta, Y. Liu, M. Shah, S. Rajan, J. Tang, and B. A. Prakash, editors, Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pages 1457–1466, New York, NY, USA, 08232020. ACM.

- S. Wang, S. Sankaran, H. Wang, and P. Perdikaris. An expert’s guide to training physics-informed neural networks, 2023. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2308.08468.pdf.

- M.-J. Xiao, T.-C. Yu, Y.-S. Zhang, and H. Yong. Physics-informed neural networks for the reynolds-averaged navier–stokes modeling of rayleigh–taylor turbulent mixing. Computers & Fluids, 266:106025, 2023.

- H. Xu, W. Zhang, and Y. Wang. Explore missing flow dynamics by physics-informed deep learning: The parameterized governing systems. Physics of Fluids, 33(9):095116, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, N. Zabaras, P.-S. Koutsourelakis, and P. Perdikaris. Physics-constrained deep learning for high-dimensional surrogate modeling and uncertainty quantification without labeled data. Journal of Computational Physics, 394(1):56–81, 2019. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).