Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. MRT-LBM

2.2. PINN-MRT

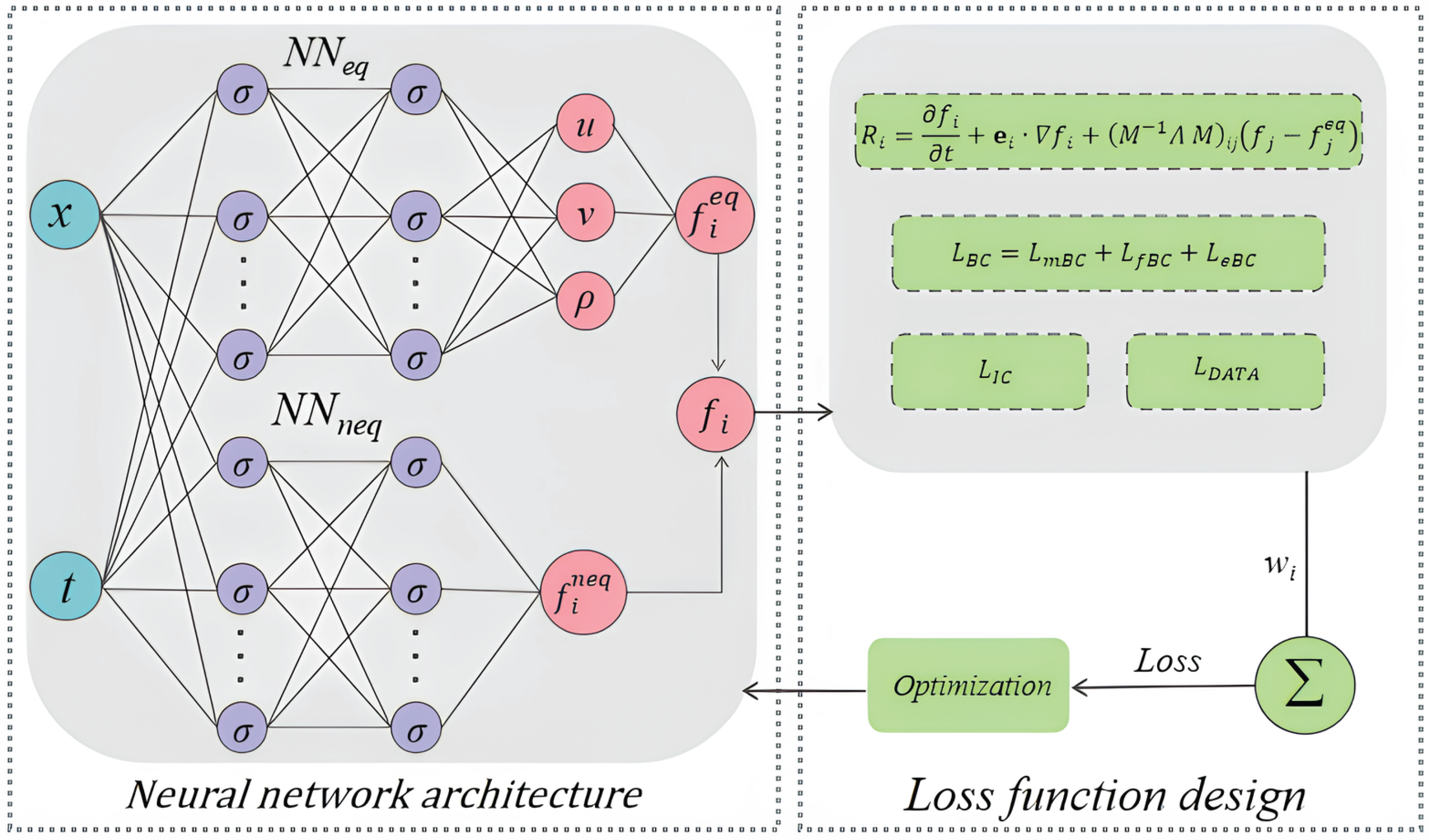

2.2.1. Neural Network Architecture

2.2.2. Loss Function Design

- Macroscopic boundary loss : Constrains the predicted macroscopic variables on the boundaries to match the prescribed physical values.

- Distribution function consistency loss : Constrains the predicted equilibrium and non-equilibrium distribution functions to match the theoretically defined boundary distributions.

- Boundary PDE residual loss : Imposes constraints on the neural network outputs by penalizing the residuals of the governing equations at the boundaries.

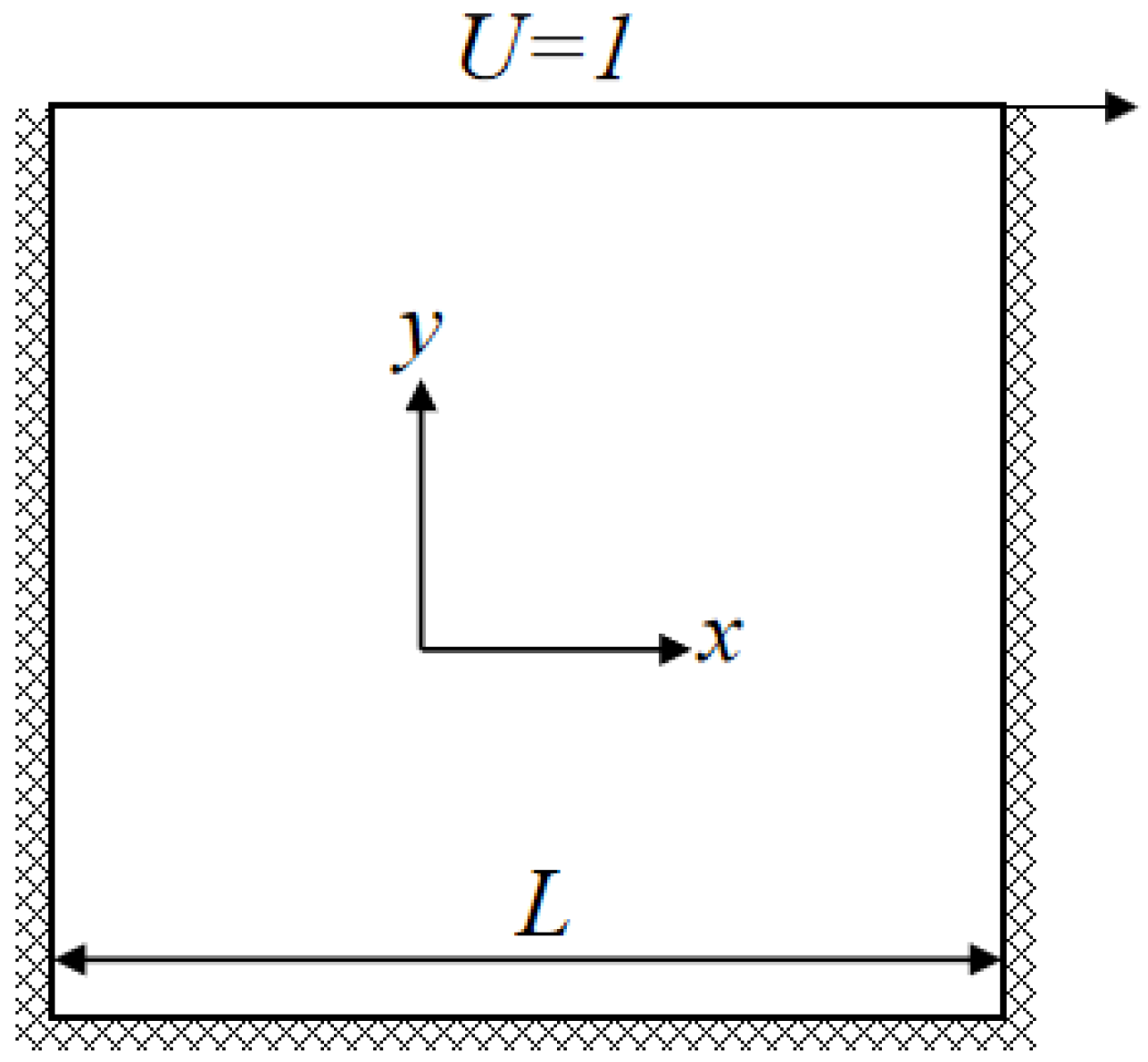

3. Benchmark Modeling

4. Results

4.1. Inverse Problem

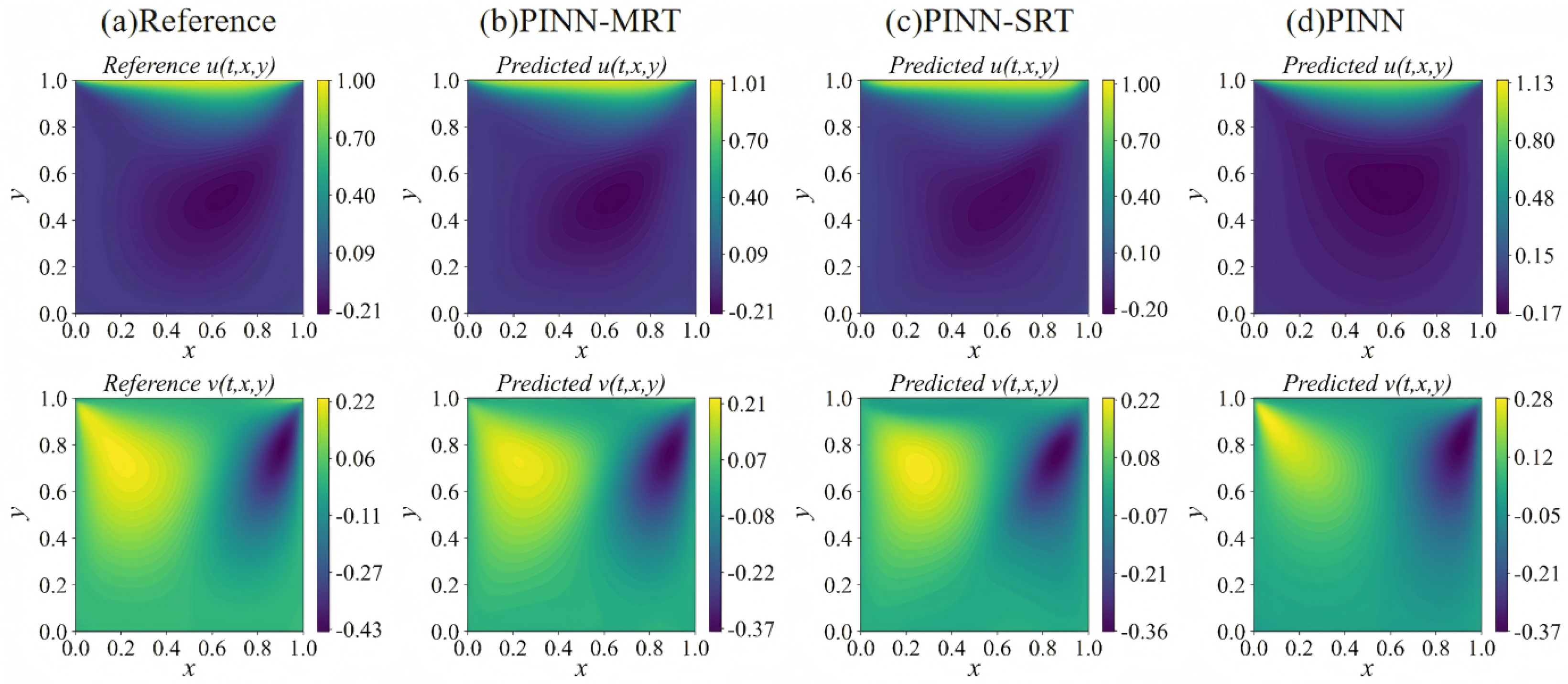

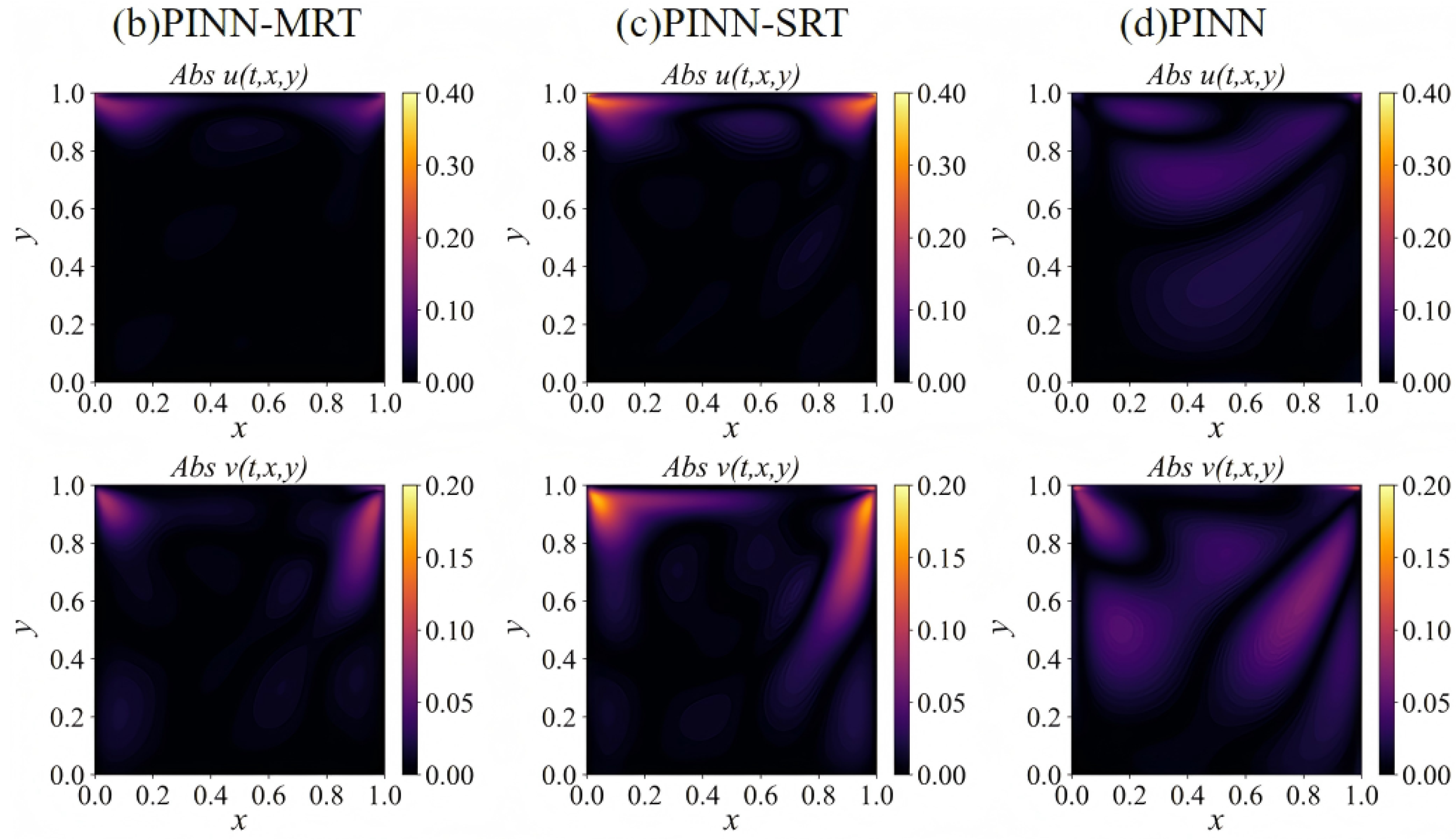

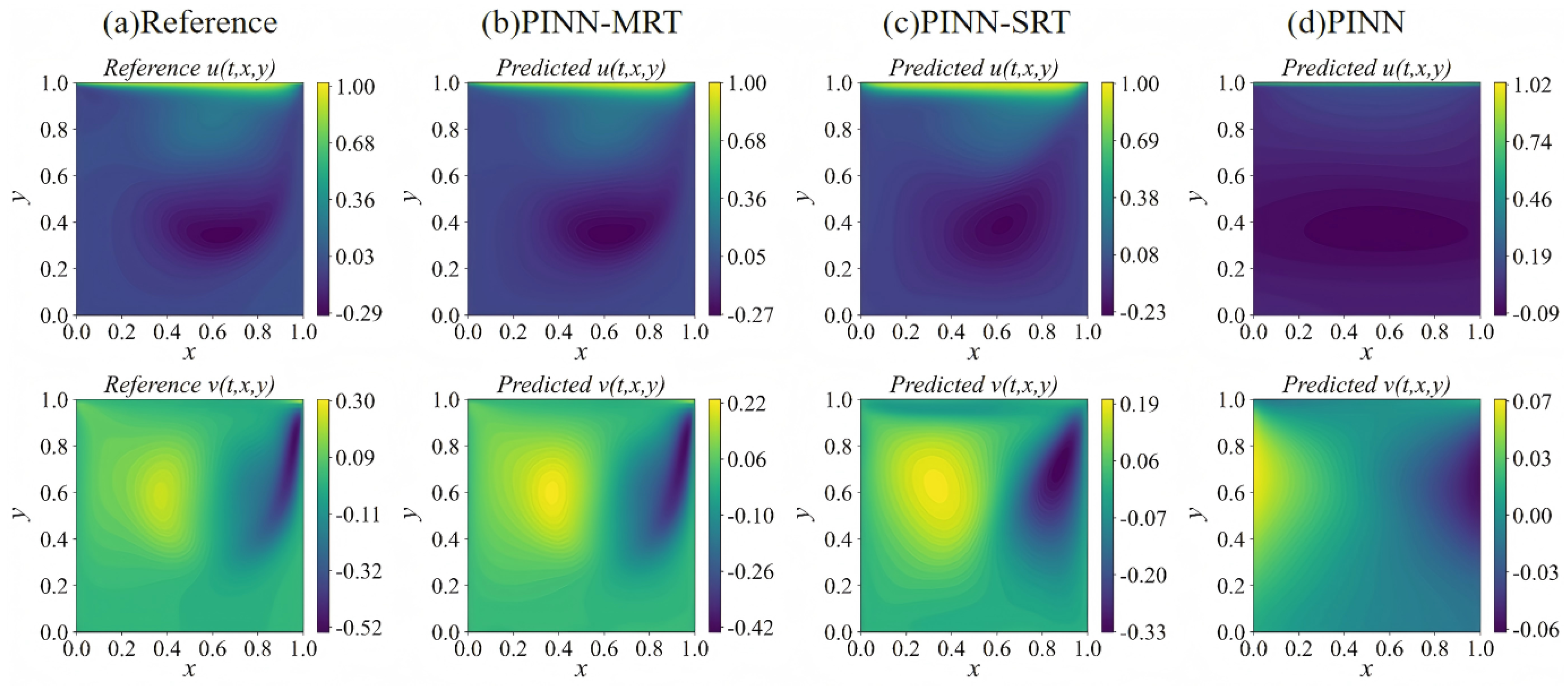

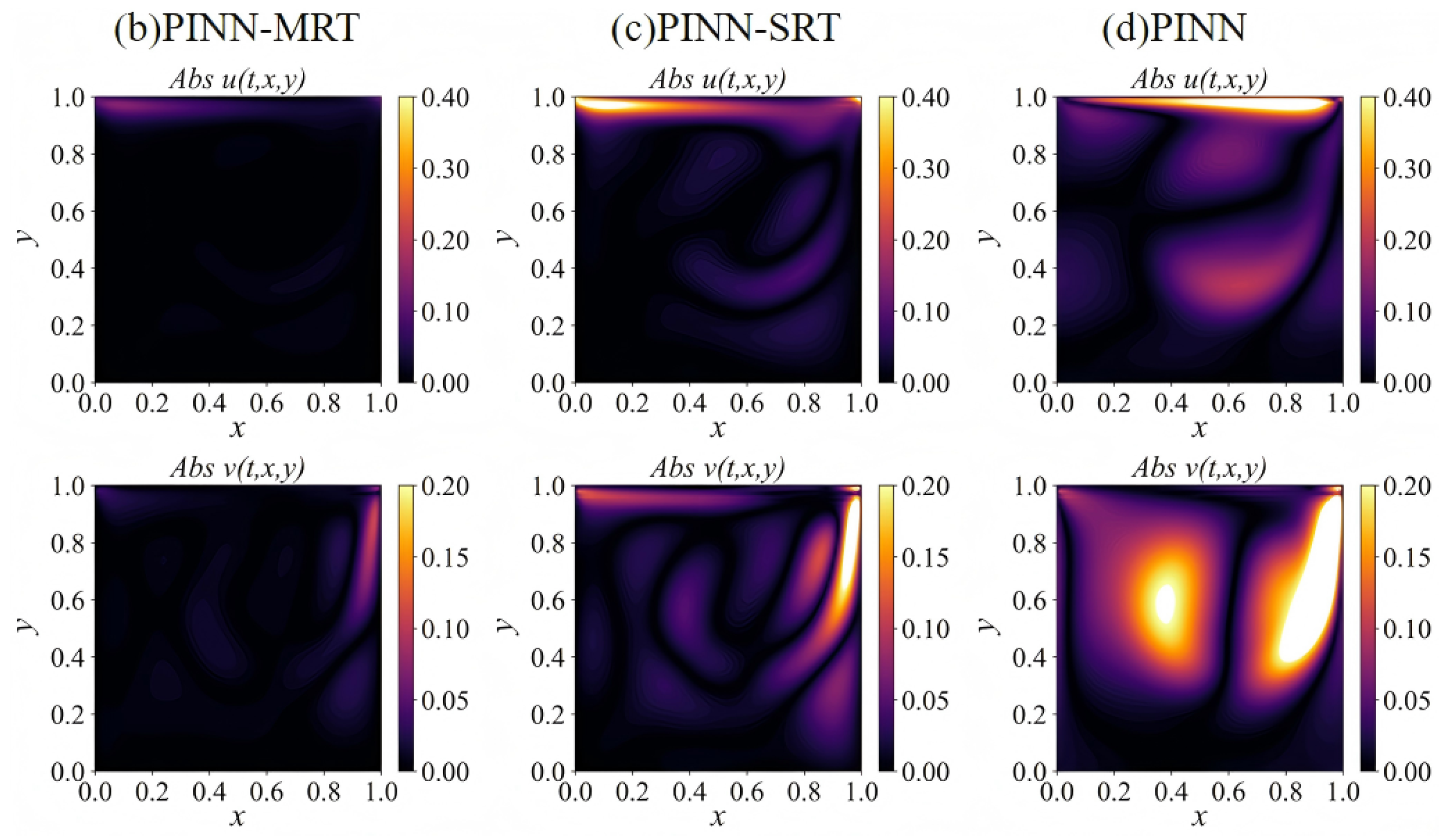

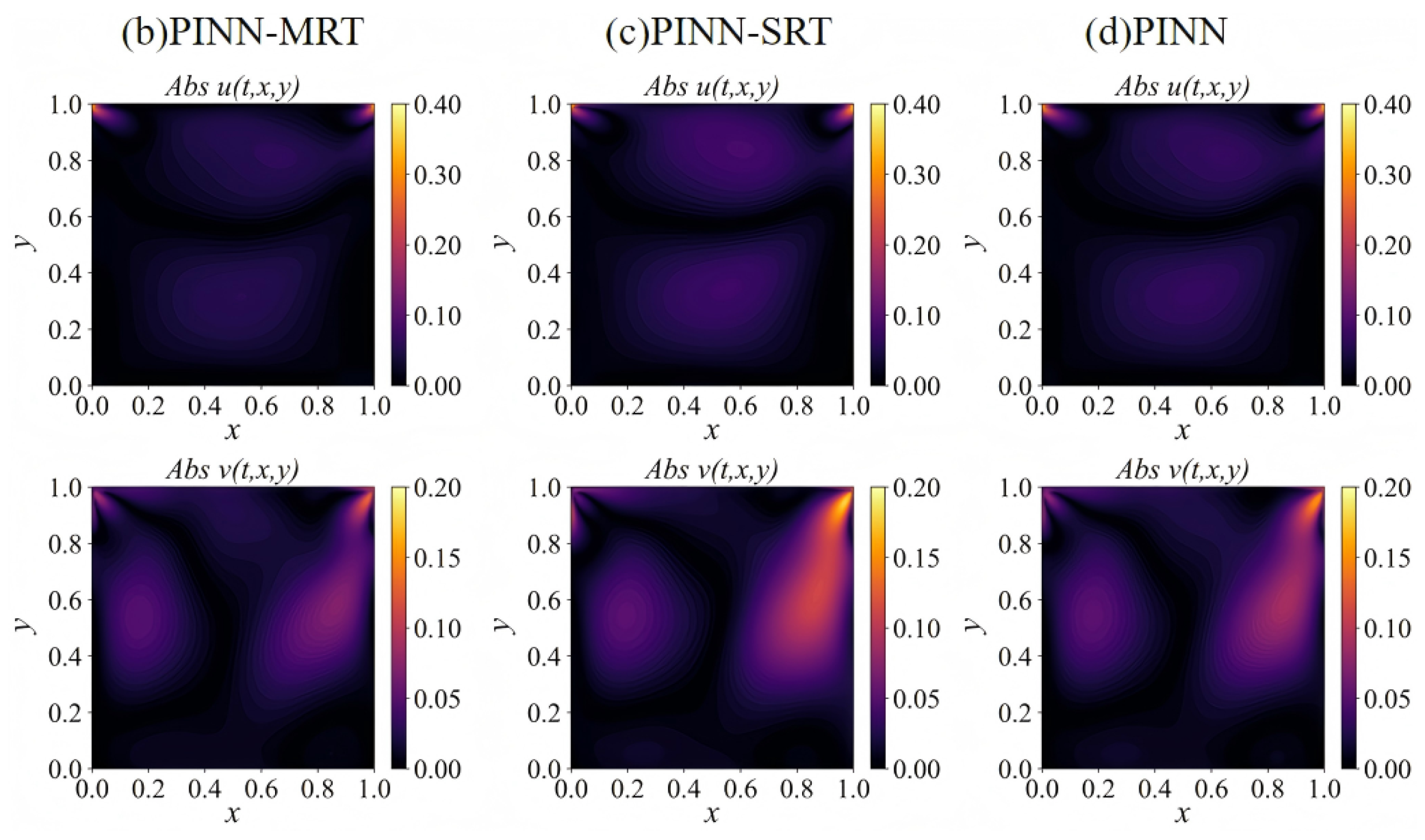

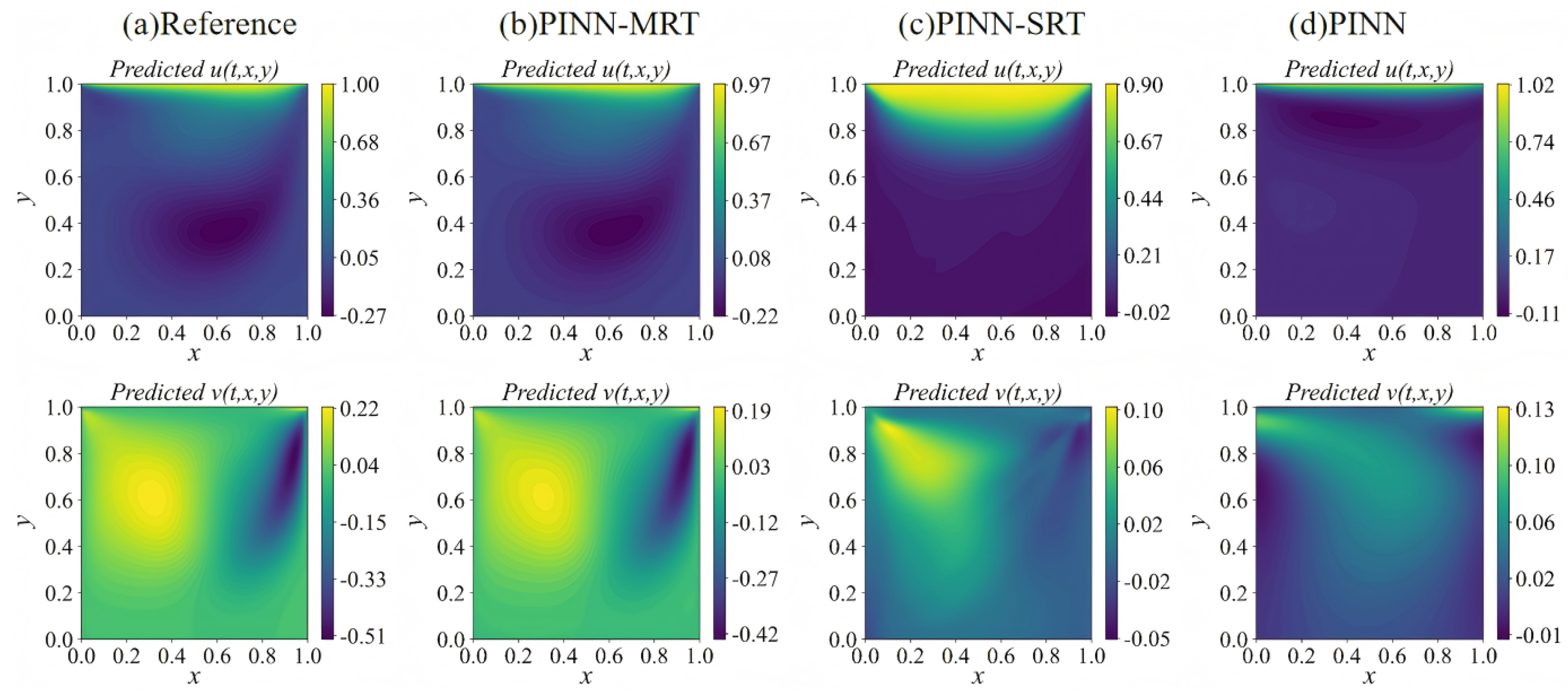

4.1.1. Flow Field Analysis

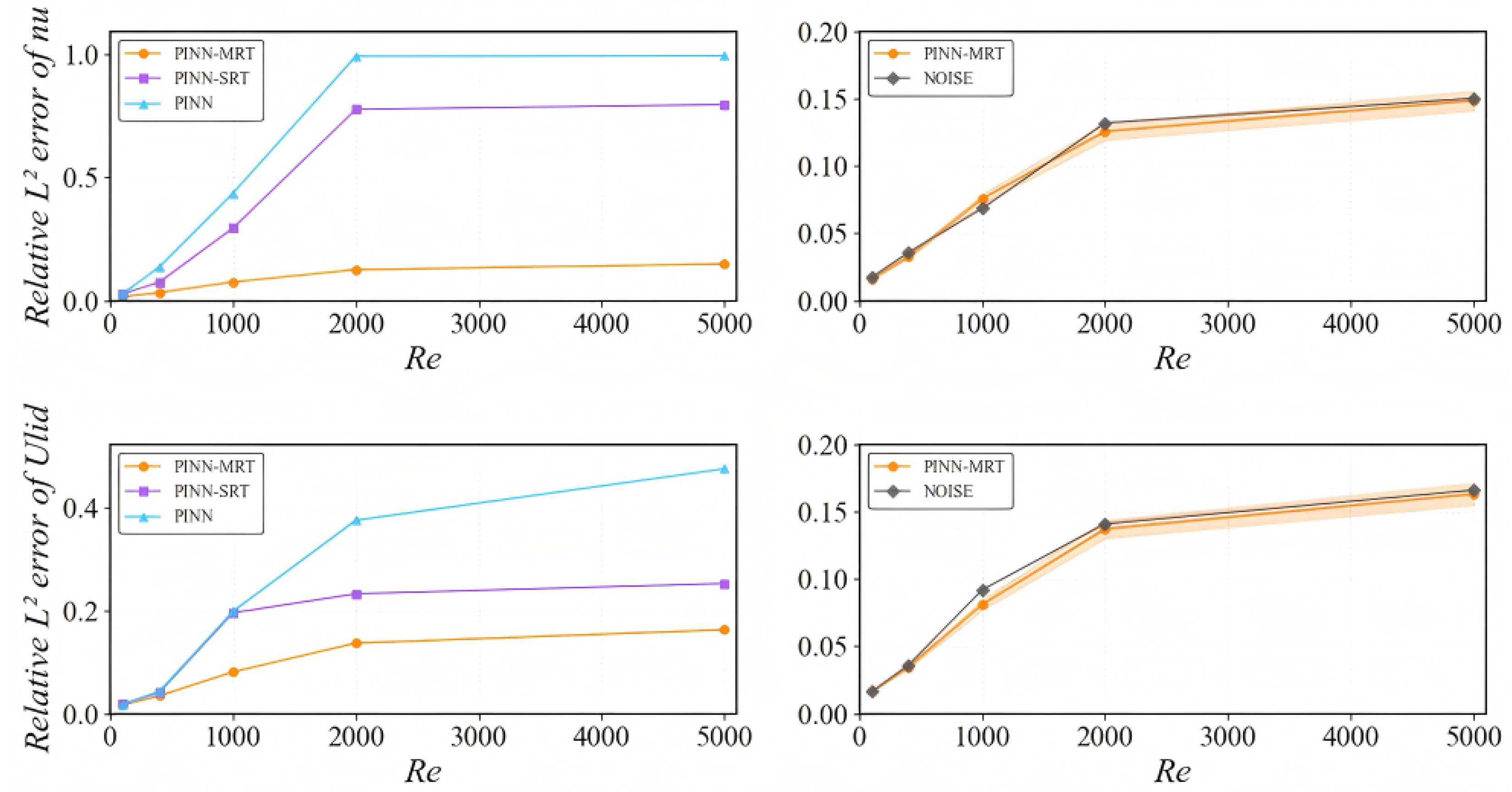

4.1.2. Parameter Inversion

4.2. Forward Problem

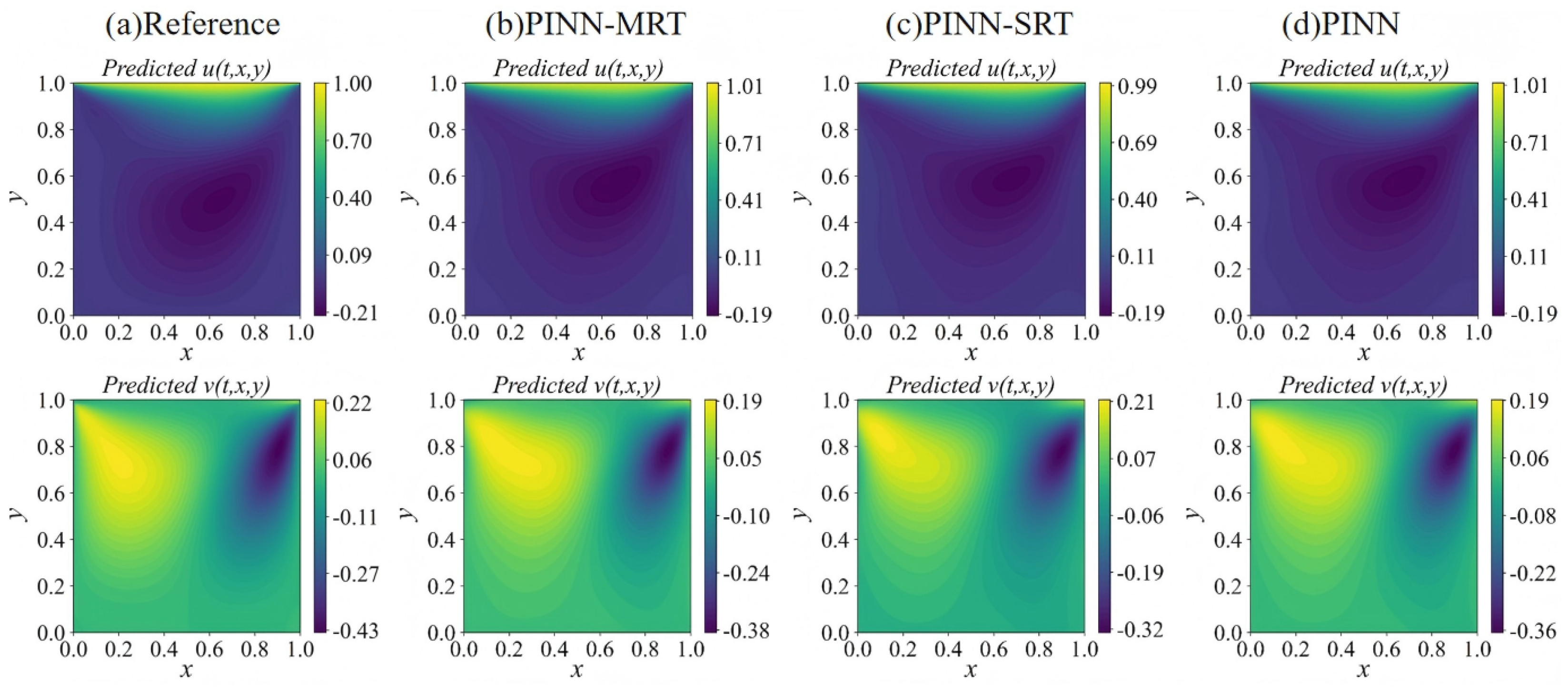

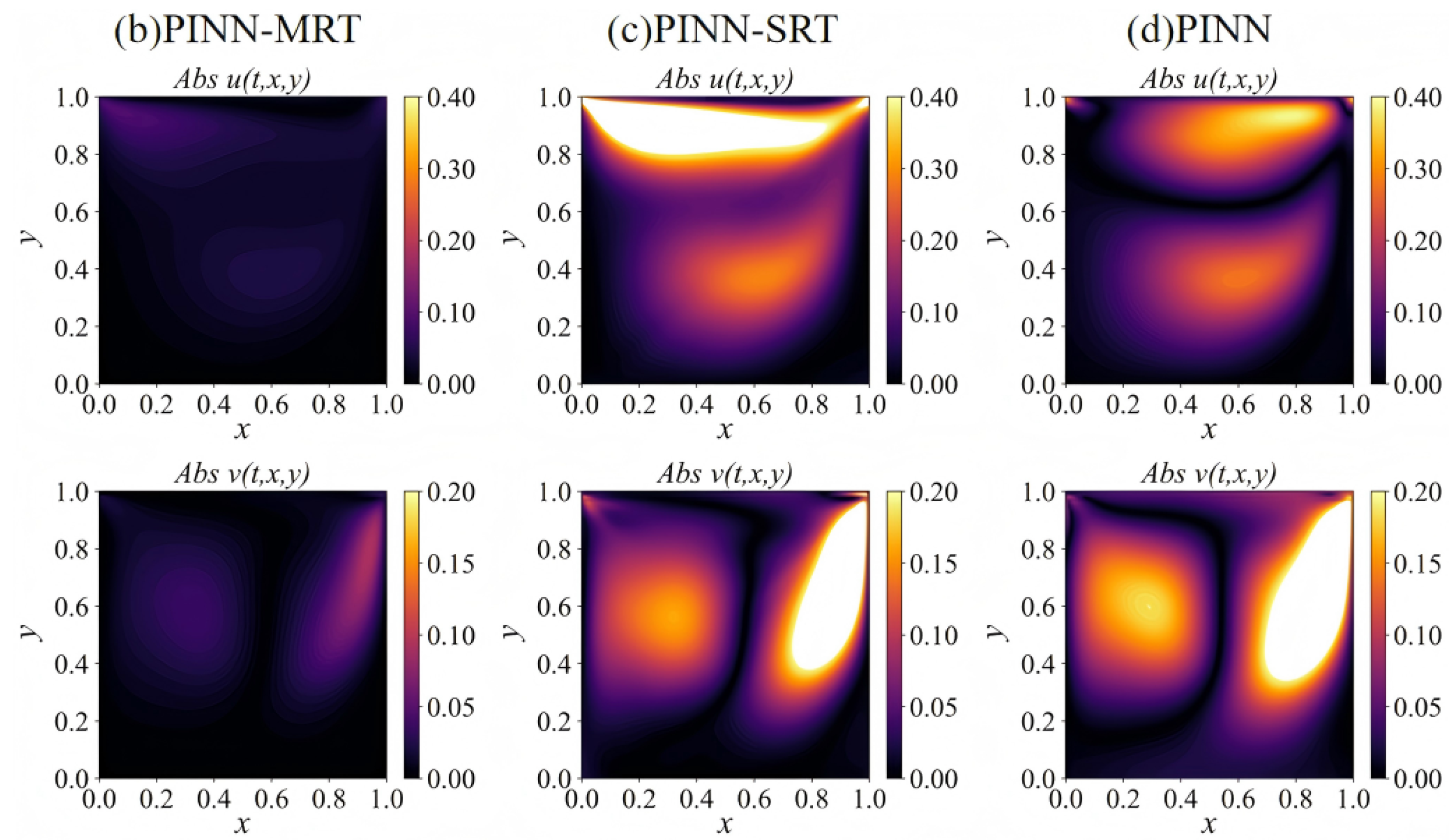

4.2.1. Flow Field Analysis

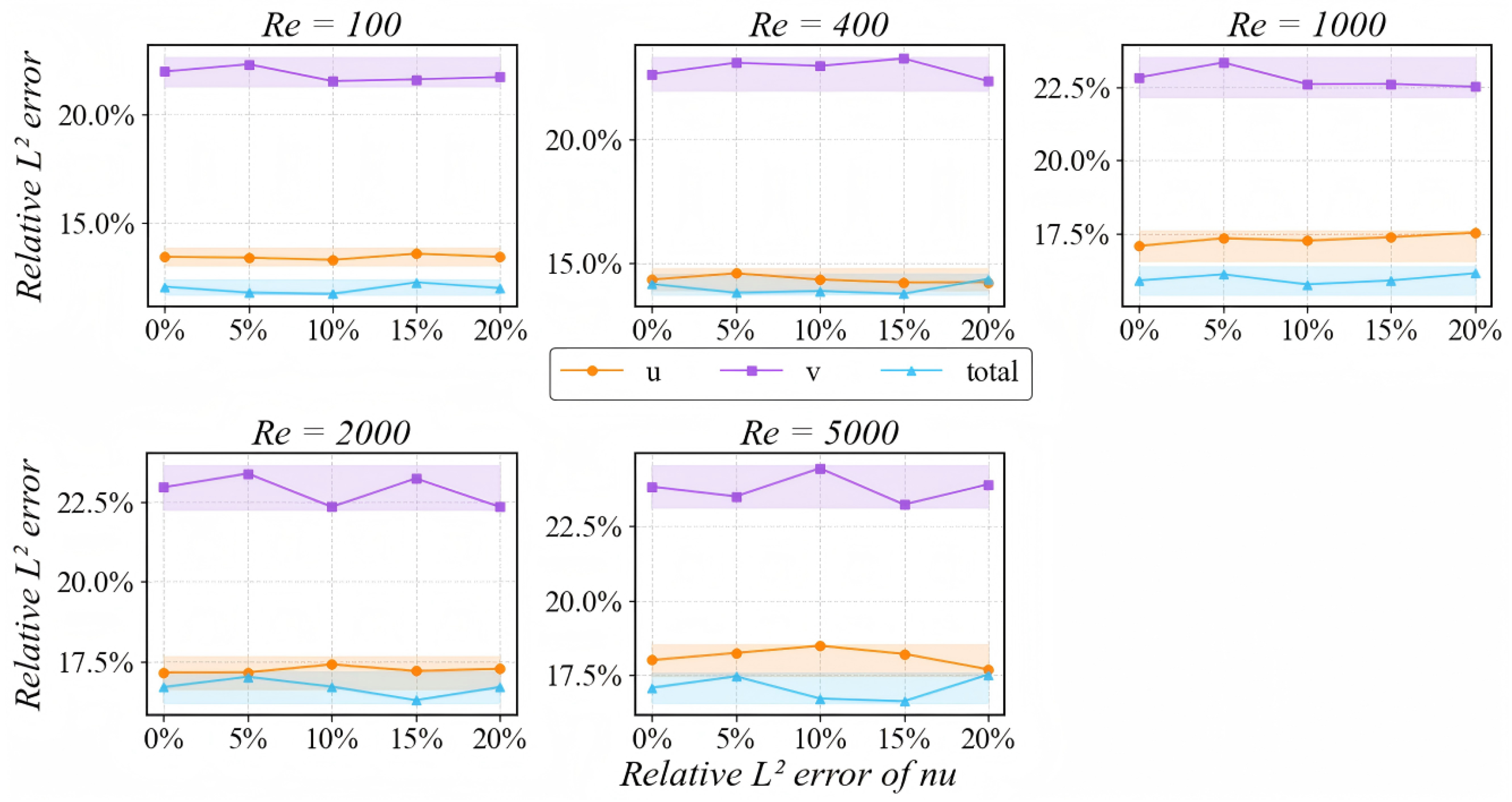

4.2.2. Viscosity Sensitivity

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Runchal, A.K. Evolution of CFD as an engineering science. A personal perspective with emphasis on the finite volume method. Comptes Rendus. Mécanique 2022, 350, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P.; Pandey, A.K.; Sirohi, R.; Hoang, A.T.; Kim, S.H. Recent advances in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modelling of photobioreactors: Design and applications. Bioresource technology 2022, 350, 126920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, J.; Zou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of flow control strategies for supersonic/hypersonic fluid dynamics. Aerospace Research Communications 2024, 2, 13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Yeoh, G.H.; Liu, C.; Tao, Y. Computational fluid dynamics: a practical approach; Elsevier, 2023.

- Hafeez, M.B.; Krawczuk, M. A Review: Applications of the Spectral Finite Element Method: MB Hafeez and M. Krawczuk. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023, 30, 3453–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cantwell, C.D.; Monteserin, C.; Eskilsson, C.; Engsig-Karup, A.P.; Sherwin, S.J. Spectral/hp element methods: Recent developments, applications, and perspectives. Journal of Hydrodynamics 2018, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droniou, J. Finite volume schemes for diffusion equations: introduction to and review of modern methods. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2014, 24, 1575–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational physics 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, E.Z.; Zeng, G.Z.; Ni, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.W.; Hao, S. Time-averaged flow field reconstruction based on a multifidelity model using physics-informed neural network (PINN) and nonlinear information fusion. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow 2024, 34, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wei, J.; Kang, L.; Liu, Y.; Rao, X. Physics-informed neural network (PINNs) for convection equations in polymer flooding reservoirs. Physics of Fluids 2025, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.; Gupta, A.; Ong, Y.S. Can transfer neuroevolution tractably solve your differential equations? IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine 2021, 16, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM review 2021, 63, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shin, S.; Kim, T.; Park, B.; Choi, H.; Lee, A.; Choi, M.; Lee, S. Physics informed neural networks for fluid flow analysis with repetitive parameter initialization. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 16740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Humieres, D. Generalized lattice-Boltzmann equations. Rarefied gas dynamics 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Shi, B.; Wang, N. Lattice BGK model for incompressible Navier–Stokes equation. Journal of Computational Physics 2000, 165, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Doolen, G.D. Lattice Boltzmann method for fluid flows. Annual review of fluid mechanics 1998, 30, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Physics-informed learning of governing equations from scarce data. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Q.; Meng, X.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks for solving forward and inverse flow problems via the Boltzmann-BGK formulation. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 447, 110676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Huang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Ji, T. A hybrid algorithm of lattice Boltzmann method and finite difference–based lattice Boltzmann method for viscous flows. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2017, 85, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Su, R.; Shen, X.; Deng, T.; Zhang, D.; Chang, D.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, S. Modeling of indoor airflow around thermal manikins by multiple-relaxation-time lattice Boltzmann method with LES approaches. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications 2020, 77, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zha, Y.; Feng, M.; Shan, M.; Yang, Y.; Yin, C.; Han, Q. Numerical investigation on jet-enhancement effect and interaction of out-of-phase cavitation bubbles excited by thermal nucleation. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 1073. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Z.; Shi, B.; Guo, Z. A multiple-relaxation-time lattice Boltzmann model for general nonlinear anisotropic convection–diffusion equations. Journal of Scientific Computing 2016, 69, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T.; Kusumaatmaja, H.; Kuzmin, A.; Shardt, O.; Silva, G.; Viggen, E.M. The lattice Boltzmann method; Vol. 10, Springer, 2017.

- Yang, Y.; Tu, J.; Shan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, H. Acoustic cavitation dynamics of bubble clusters near solid wall: A multiphase lattice Boltzmann approach. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2025, 114, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, M.; Zha, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Yin, C.; Han, Q. Morphological characteristics and cleaning effects of collapsing cavitation bubble in fractal cracks. Physics of Fluids 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, D.; Wu, H.; Qin, C.; Fei, Q. Physics-informed neural networks for solcing inverse problems in phase field models. Neural Networks, 1076. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap, A.D.; Mao, Z.; Adams, N.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks for inverse problems in supersonic flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 466, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Pestourie, R.; Yao, W.; Wang, Z.; Verdugo, F.; Johnson, S.G. Physics-informed neural networks with hard constraints for inverse design. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2021, 43, B1105–B1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Cai, S.; Li, H.; Karniadakis, G.E. NSFnets (Navier-Stokes flow nets): Physics-informed neural networks for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 426, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, P.; Luo, L.S. Theory of the lattice Boltzmann method: Dispersion, dissipation, isotropy, Galilean invariance, and stability. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 61, 6546–6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markidis, S. The Old and the New: Can Physics-Informed Deep-Learning Replace Traditional Linear Solvers? 2021; arXiv:math.NA/2103.09655]. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Yao, J.; Su, C.; Su, H.; Wang, Z.; Lu, F.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lu, L.; et al. 2023; arXiv:cs.LG/2306.08827].

- Jagtap, A.D.; Karniadakis, G.E. Extended physics-informed neural networks (XPINNs): A generalized space-time domain decomposition based deep learning framework for nonlinear partial differential equations. Communications in Computational Physics 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Yao, W. Accelerating physics-informed neural network training with prior dictionaries. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.08151, arXiv:2004.08151 2020.

- Yu, J.; Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Karniadakis, G.E. Gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse PDE problems. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2022, 393, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Network structure | 5-layer fully connected network (1 input, 3 hidden, 1 output) |

| Hidden neurons | 60 neurons per hidden layer |

| Activation function | Tanh |

| Trainable parameter | Both and are randomly initialized in |

| Loss function | |

| Data source | FDM |

| Data location | Random sampling |

| Sampling distribution | 20,000 collocation pts; 5,000 boundary pts; 1,000 data pts |

| Optimizer | Adam (80,000 iterations, initial LR , exponential decay) |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Network structure | 7-layer fully connected network (1 input, 5 hidden, 1 output) |

| Hidden neurons | 60 neurons per hidden layer in ; 100 in |

| Activation function | Tanh |

| Trainable parameter | None |

| Loss function | |

| Data source | None |

| Data location | None |

| Sampling distribution | 20,000 collocation pts; 5,000 boundary pts |

| Optimizer | Adam (80,000 iterations, initial LR , exponential decay) |

| Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Re = 100 | ||

| PINN | [0.0005, 0.0763] | [0.0005, 0.0654] |

| PINN-SRT | [0.0002, 0.0531] | [0.0003, 0.0526] |

| PINN-MRT | [0.0003, 0.0447] | [0.0004, 0.0310] |

| Re = 1000 | ||

| PINN | – | – |

| PINN-SRT | [0.0005, 0.2195] | [0.0001, 0.1318] |

| PINN-MRT | [0.0005, 0.0573] | [0.0001, 0.0635] |

| PINN-MRT | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re = 100 | 9.067 | 11.942 | 4.549 |

| Re = 1000 | 12.179 | 17.048 | 9.894 |

| Re = 2000 | 14.088 | 20.369 | 13.845 |

| Re = 5000 | 15.281 | 21.262 | 14.121 |

| Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Re = 100 | ||

| PINN | [0.0001, 0.0765] | [0.0000, 0.0248] |

| PINN-SRT | [0.0004, 0.0851] | [0.0005, 0.1050] |

| PINN-MRT | [0.0003, 0.0447] | [0.0004, 0.0310] |

| Re = 400 | ||

| PINN | [0.0002, 0.3099] | [0.0059, 0.3688] |

| PINN-SRT | [0.0041, 0.5389] | [0.0003, 0.3197] |

| PINN-MRT | [0.0003, 0.1114] | [0.0004, 0.0508] |

| PINN-MRT | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re = 100 | 13.436 | 22.014 | 12.058 |

| Re = 400 | 14.328 | 22.669 | 14.145 |

| Re = 1000 | 17.086 | 22.834 | 15.910 |

| Re = 2000 | 17.152 | 22.962 | 16.691 |

| Re = 5000 | 18.003 | 23.815 | 17.076 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).