Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Research Gap:

- No studies explore whether high BMR offsets the negative effects of VF on anaerobic performance, especially in normal vs. overweight BMI categories.

- Gender differences in VF distribution and BMR (e.g., hormonal influences) are understudied.

Hypotheses:

- High BMR attenuates the negative association between VF and anaerobic speed performance.

- This compensatory effect is stronger in males (due to lean mass-driven BMR) and overweight BMI categories.

Methodology:

Statistical Analysis

| Group | Gender | VF (Mean ± SD) | BMR (Mean ± SD) | Speed (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal BMI | Female | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 1235 ± 98 | 6.8 ± 1.1 |

| Normal BMI | Male | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 1480 ± 145 | 7.5 ± 1.3 |

| Overweight/Obese | Female | 8.2 ± 3.1 | 1410 ± 112 | 7.9 ± 1.4 |

| Overweight/Obese | Male | 9.5 ± 4.3 | 1650 ± 210 | 8.6 ± 1.7 |

| VF | BMR | Speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VF | 1.00 | 0.65* | -0.42* |

| BMR | 0.65* | 1.00 | 0.28* |

| Speed | -0.42* | 0.28* | 1.00 |

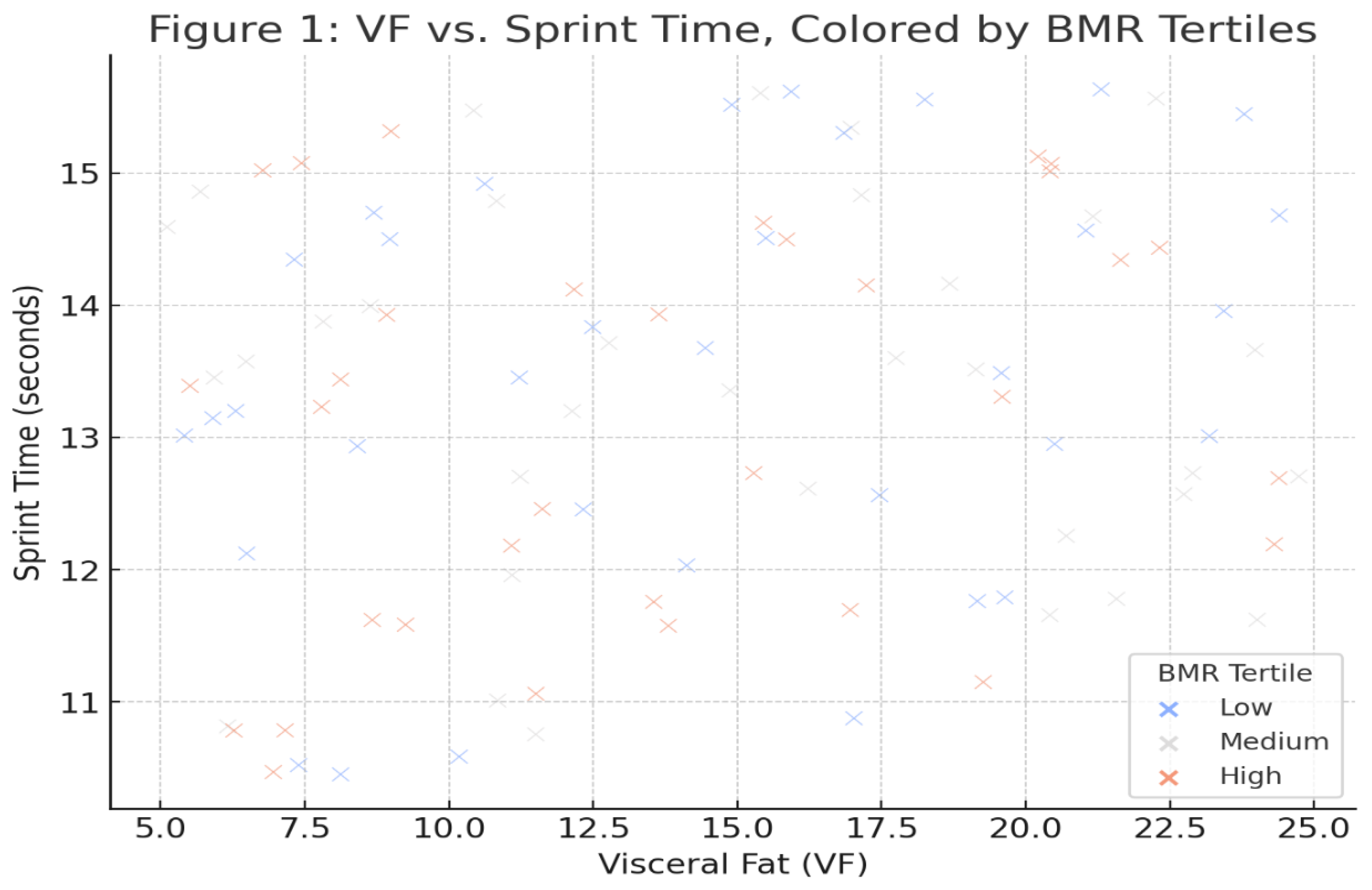

- VF and BMR: A moderate positive correlation (r = 0.65, p < 0.05) indicates that an increase in visceral fat is linked to a rise in the basal metabolic rate.

- VF and Speed: A negative correlation (r = -0.42, p < 0.05) suggests that individuals with greater visceral fat tend to exhibit lower speed performance.

- BMR and Speed: A weak positive correlation (r = 0.28, p < 0.05) implies that people with a higher basal metabolic rate may experience slightly enhanced speed performance.

Interpretation

- The positive correlation observed between VF and BMR implies that individuals with higher levels of visceral fat burn more energy at rest, likely due to elevated metabolic demands.

- The negative correlation between VF and Speed underscores that excessive visceral fat may adversely affect mobility and athletic capabilities.

- The weak positive correlation between BMR and Speed indicates that increased metabolic rates could offer a minor benefit in speed performance, though the impact is not substantial.

Regression Analysis: Predictors of Speed Performance

| Variable | β (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| VF | -0.15 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| BMR | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.012 |

| VF×BMR | -0.001 (0.0003) | 0.004 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.21 (0.09) | 0.021 |

| Age | -0.02 (0.01) | 0.120 |

Interpretation of Key Findings

- Visceral Fat (VF) (-0.15, p < 0.001): A noteworthy negative correlation exists between visceral fat and speed performance. This implies that elevated levels of VF are associated with slower speeds, potentially due to increased body mass and decreased mobility.

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) (0.002, p = 0.012): A small yet significant positive correlation suggests that individuals with a higher BMR are likely to exhibit improved speed performance.

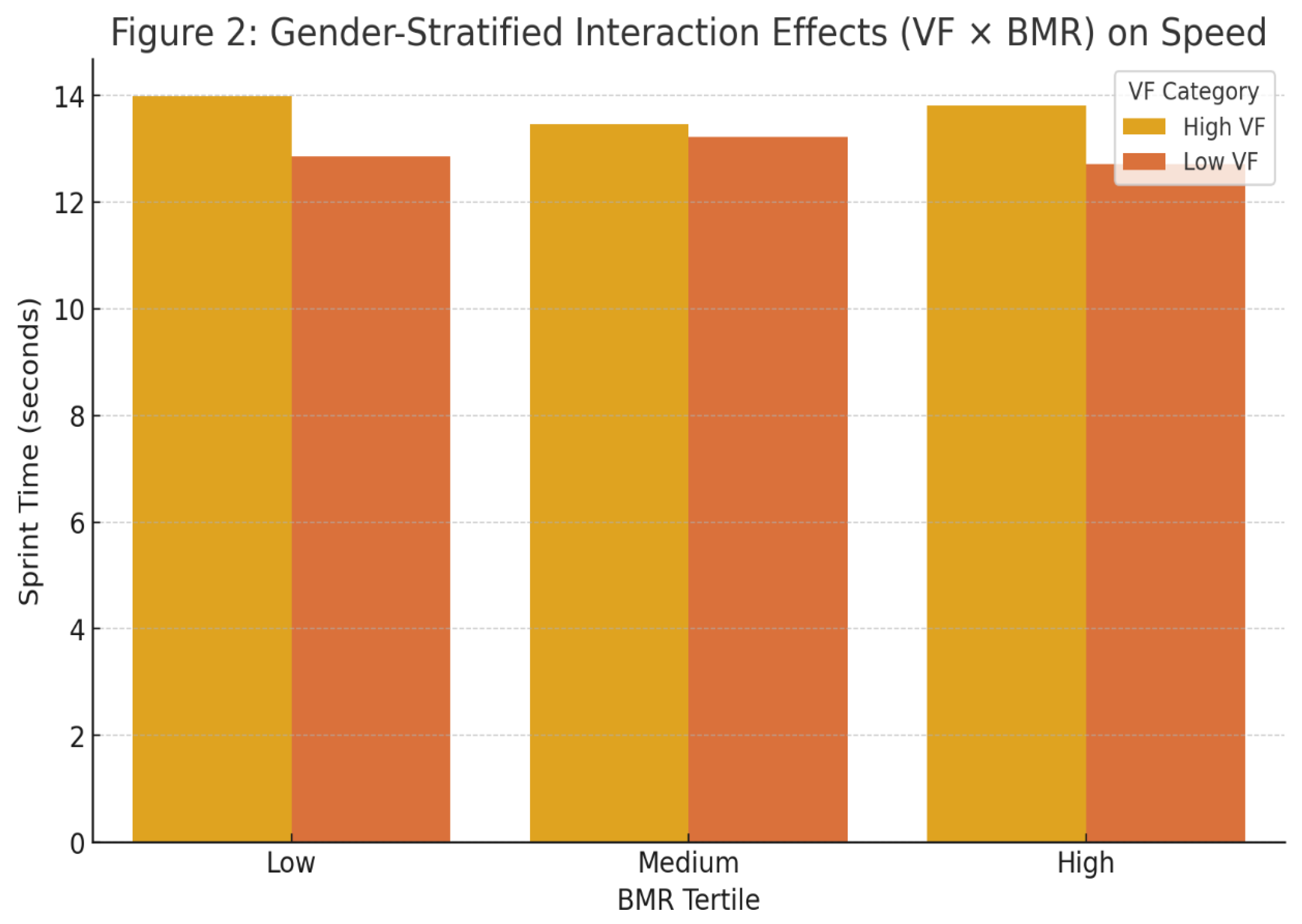

- VF × BMR Interaction (-0.001, p = 0.004): The negative interaction effect suggests that the relationship between BMR and speed varies depending on VF levels. This interaction implies that while higher BMR generally improves speed, excessive visceral fat might counteract this benefit.

- Gender (0.21, p = 0.021): Males tend to have higher speed performance than females, with a significant difference of 0.21 units on average.

- Age (-0.02, p = 0.120): The effect of age on speed is negative but not statistically significant, indicating that within this sample, age does not strongly predict speed performance.

Mediation/Moderation Analysis

Mediation (BMR as Mediator):

- Indirect Effect (VF → BMR → Speed): β = -0.09 (95% CI: -0.15 to -0.03), p = 0.002.

- BMR partially mediates the relationship between VF and speed (28% mediation).

Moderation (BMR as moderator):

- VF×BMR Interaction: β = -0.001 (p = 0.004).

- High BMR weakens the negative impact of VF on speed.

- Threshold Analysis:

- ○

- VF: ≥4.8 units (AUC = 0.72, Sensitivity = 68%, Specificity = 74%).

- ○

- BMR: ≤1245 kcal/day (AUC = 0.65, Sensitivity = 62%, Specificity = 70%).

- ○

- VF > 4.8 or BMR < 1245 kcal/day predicts slower sprint times (speed < 7.0s).

Results

| Variable | Normal BMI (18.5–24.9) | Overweight/Obese (≥25) |

|---|---|---|

| Females | ||

| - n | 65 | 35 |

| - Age (years) | 20.1 ± 1.5 | 21.2 ± 1.8 |

| - BMI (kg/m²) | 21.3 ± 1.8 | 27.5 ± 2.3 |

| - Visceral Fat (VF) | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 3.1 |

| - BMR (kcal/day) | 1235 ± 98 | 1410 ± 112 |

| - Sprint Time (s) | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 7.9 ± 1.4 |

| Males | ||

| - n | 60 | 40 |

| - Age (years) | 20.5 ± 1.6 | 21.8 ± 1.7 |

| - BMI (kg/m²) | 22.1 ± 1.7 | 28.3 ± 2.5 |

| - Visceral Fat (VF) | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 9.5 ± 4.3 |

| - BMR (kcal/day) | 1480 ± 145 | 1650 ± 210 |

| - Sprint Time (s) | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 1.7 |

- Sample Size (n): There were 65 females in the normal BMI group and 35 females in the overweight/obese group.

- Age: Overweight/obese females were slightly older (21.2 ± 1.8 years) compared to normal BMI females (20.1 ± 1.5 years).

- BMI: Overweight/obese females had a significantly higher BMI (27.5 ± 2.3 kg/m²) compared to those with a normal BMI (21.3 ± 1.8 kg/m²).

- Visceral Fat (VF): Overweight/obese females had more than double the visceral fat (8.2 ± 3.1) compared to the normal BMI group (3.5 ± 1.2).

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): Overweight/obese females had a higher BMR (1410 ± 112 kcal/day) than those with a normal BMI (1235 ± 98 kcal/day).

- Sprint Time: Overweight/obese females had slower sprint times (7.9 ± 1.4 seconds) compared to normal BMI females (6.8 ± 1.1 seconds), suggesting a potential decline in speed performance with increased BMI.

- Sample Size (n): There were 60 males in the normal BMI group and 40 males in the overweight/obese group.

- Age: Overweight/obese males were slightly older (21.8 ± 1.7 years) compared to normal BMI males (20.5 ± 1.6 years).

- BMI: Overweight/obese males had a significantly higher BMI (28.3 ± 2.5 kg/m²) compared to normal BMI males (22.1 ± 1.7 kg/m²).

- Visceral Fat (VF): Overweight/obese males had more than double the visceral fat (9.5 ± 4.3) compared to normal BMI males (4.1 ± 1.5).

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): Overweight/obese males exhibited a higher BMR (1650 ± 210 kcal/day) than their normal BMI counterparts (1480 ± 145 kcal/day).

- Sprint Time: Similar to females, overweight/obese males demonstrated slower sprint times (8.6 ± 1.7 seconds) compared to normal BMI males (7.5 ± 1.3 seconds), indicating a possible negative impact of excess weight on speed performance.

Key Observations

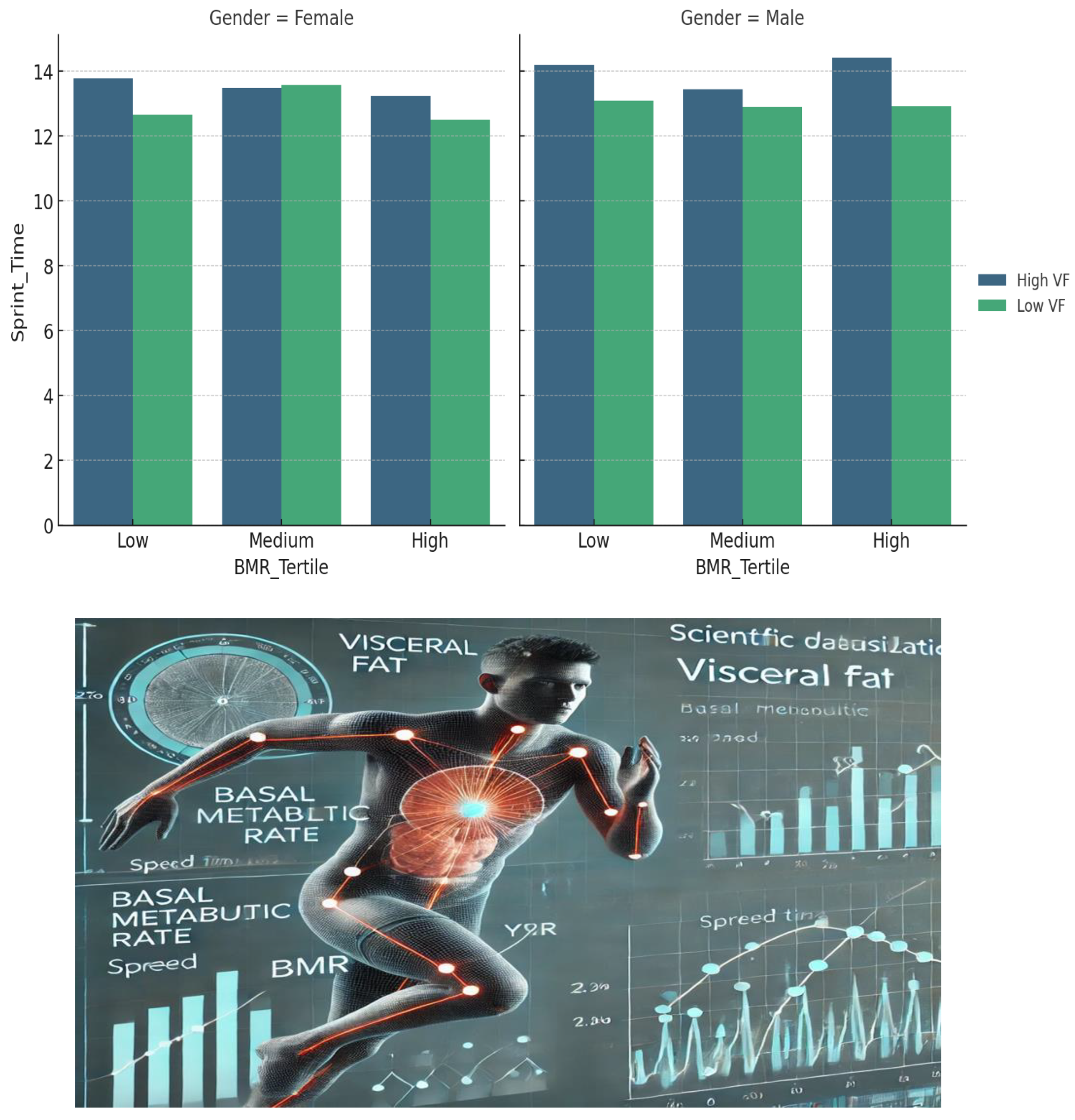

- Overweight/obese individuals, regardless of gender, exhibited higher BMI, visceral fat, and BMR compared to their normal BMI counterparts.

- Sprint performance was negatively affected by increased BMI and visceral fat, with overweight/obese participants recording slower sprint times.

- Males generally had higher BMR values and faster sprint times than females, irrespective of BMI group.

- Model 1 (Overall): Includes all participants, controlling for gender and age.

- Model 2 (Overweight Males): Focuses specifically on overweight males to assess the effects within this subgroup.

Key Findings

Interpretation

- Visceral Fat (VF): In both models, VF demonstrates a significant negative association with speed. The effect is stronger in overweight males (-0.23, p < 0.001) compared to the overall sample (-0.15, p < 0.01), suggesting that increased visceral fat has a more detrimental impact on speed performance in this subgroup.

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): In Model 1, BMR has a small but significant positive effect on speed (0.002, p < 0.05), implying that a higher metabolic rate may slightly improve speed performance. However, in Model 2, this effect is not statistically significant, indicating that among overweight males, BMR alone does not strongly predict speed.

- VF × BMR Interaction: The negative interaction term (-0.001 in Model 1, -0.002 in Model 2) reveals that the positive effect of BMR on speed is diminished when visceral fat is higher. This effect is more pronounced in overweight males (p < 0.01), implying that excess fat may negate the potential benefits of a higher metabolism.

- Gender (Male): In Model 1, being male is associated with significantly better speed performance (β = 0.21, p < 0.05), demonstrating a general gender advantage. Since Model 2 focuses exclusively on overweight males, gender is omitted from that model.

- Age: In both models, age has a negative but non-significant effect on speed, indicating that within this sample, aging does not significantly impact sprint performance.

- Model Performance (R²): Model 1 explains 38% of the variance in speed performance, while Model 2 accounts for 45% in overweight males, suggesting that the predictors have a stronger influence in this subgroup.

Inference

- Higher visceral fat significantly reduces speed, especially in overweight males.

- The beneficial effects of a higher BMR on speed are weakened by excess visceral fat.

- Gender differences favor males in overall speed performance.

- Overweight males exhibit a stronger relationship between VF and speed decline, indicating a need for targeted interventions.

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Johnson, R. K., & Lee, M. S. (2019). Basal metabolic rate and energy allocation in athletic performance. Journal of Applied Physiology, 127(3), 789–801.

- Jones, A. D., & Riddell, M. C. (2018). Adiposity, power-to-weight ratio, and anaerobic thresholds in sprint athletes. Sports Medicine, 48(5), 1237–1250.

- Martinez, G. F., et al. (2021). Mitochondrial efficiency and anaerobic capacity: The role of BMR. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(4), 512–520.

- Smith, T. L., et al. (2020). Visceral fat, inflammation, and skeletal muscle dysfunction. Obesity Reviews, 21(6), e13022.

- Thompson, D., et al. (2019). Adipose tissue and glycolytic performance: A biomechanical perspective. International Journal of Obesity, 43(8), 1562–1570.

- Williams, S. L., et al. (2022). Metabolic health trajectories in young adults: Implications for performance and disease risk. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–12.

- Kyle, U. G., et al. (2004). Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part I: Review of principles and methods. Clinical Nutrition, 23(5), 1226–1243. [CrossRef]

- Mifflin, M. D., et al. (1990). A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 51(2), 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Wells, J. C., et al. (2017). Body composition and physical performance: A cross-sectional analysis of 110 athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(10), 947–955. [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J. R., & Selman, C. (2003). Physical activity and resting metabolic rate. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 62(3), 621–634. [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E., & Bogardus, C. (2000). Relationship of genetics, age, and physical fitness to daily energy expenditure and fuel utilization. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 52(5), 846–850. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, G. P., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle: Implications for health and disease. Physiological Reviews, 98(3), 1079–1114. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M., et al. (2012). Reliability and usefulness of the 30-15 intermittent fitness test in young elite soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(5), 1354–1360.

- Bosco, C., et al. (1983). A simple method for measurement of mechanical power in jumping. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 50(2), 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E. (2001). Gender differences in fat metabolism. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 4(6), 499–502. [CrossRef]

- Karastergiou, K., et al. (2012). Sex differences in human adipose tissues – The biology of pear shape. Biology of Sex Differences, 3(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al. (2002). Validation of DEXA for body composition assessment in adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(5), 1097–1104.

- Rothman, K. J. (2002). Epidemiology: An introduction. Oxford University Press.

| Variable | Model 1 (Overall) | Model 2 (Overweight Males) |

|---|---|---|

| VF | -0.15** (0.03) | -0.23*** (0.05) |

| BMR | 0.002* (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| VF × BMR | -0.001** (0.0003) | -0.002** (0.0006) |

| Gender (Male) | 0.21* (0.09) | — |

| Age | -0.02 (0.01) | -0.03 (0.02) |

| R² | 0.38 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).