I. Introduction and Background

The detection of gas leaks [

1,

2,

3] is a widely studied problem in energy distribution, refrigeration, compressed-air, and vacuum systems [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], and in the certification of sealed structures for the packaging, automotive, and aerospace industries [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. In many cases, reliable identification of leaks, either during manufacture or after deployment, is critically important to both the safety and efficiency of these systems [

1,

6,

7,

8,

17].

At the highest level, detection methods can be classified [

2,

3] according to whether their primary utility is for

pinpointing the location or

quantifying the size of a given leak. These are sometimes delineated as ‘point source’ versus ‘systemic’ methods [

10]. Both types have important use-cases, and in fact some techniques are capable of determining, within certain limits, both the location and the size of a leak.

The size of a leak is characterized by its ‘leak rate’,

qL = Δ(

P·V)/Δ

t (e.g., with S.I. units of Pa m

3 s

-1) [

1], which essentially predicts the loss (or gain) of pressure per unit time in a fixed volume. Quantitative methods are often compared on the basis of their minimum detectable leak rate,

qL,min. Systemic tracer-gas (typically helium) techniques that use mass spectrometry are the gold standard, and can detect leak rates as small as ~10

-12 Pa m

3 s

-1 when referenced to vacuum [

4]. However, these systems are relatively complex and costly. Much simpler pressure-change techniques can achieve sensitivities approaching ~ 10

-6 Pa m

3 s

-1 under optimal conditions [

17].

To locate a leak, visual ‘bubble inspection’ tests are commonly employed. While these are somewhat laborious and time-consuming, a skilled technician can locate leaks as small as ~10

-4 Pa m

3 s

-1 [

17]. An alternative option is provided by ‘sniffers’ [

1], which are variously based on thermal conductivity, electrochemical, or mass-spectrometry sensors, and are able to detect and locate leaks in the ~10

-6 - 10

-2 Pa m

3 s

-1 range [

4]. However, these devices are often gas-specific and can be challenging to use in closed areas where the target gas accumulates, or in open, windy areas where the target gas is not efficiently collected.

Ultrasonic [

2,

3] (i.e., aero-acoustic [

19,

20]) leak detection relies on the airborne acoustic signals emitted by a turbulent gas jet. Its attributes include a passive and non-invasive nature and an ability to sense a leak for any type of gas. However, it is traditionally viewed as a low-sensitivity tool, useful mainly for rapid but strictly qualitative identification and localization of a leak [

2,

4]. In spite of this, the commercial and industrial use of ultrasonic leak detectors is on the rise, driven in part by advances in the on-board computing and signal processing capabilities of low-cost portable instruments. For example, ‘ultrasonic sniffers’ [

21] are sometimes preferred over traditional chemical sniffers for locating leaks in HVAC and refrigeration systems [

9].

In order to generate detectable sound, a gas leak must lie in a turbulent flow regime [

22], which places a fundamental lower limit (e.g.,

qL,min ~ 10

-4 to 10

-3 Pa m

3 s

-1 [

1,

4]) on the detectable leak rate. However, the practical limit is often significantly higher (e.g.,

qL,min ~ 10

-1 Pa m

3 s

-1 [

17]), due to the impact of interfering signals in the environment and electrical noise in the ultrasonic microphone. Thus, airborne ultrasound techniques have traditionally been restricted to locating relatively large leaks (i.e., large holes, and at relatively large pressures). This is illustrated by several recent studies [

5,

6,

7,

9,

13,

16,

19,

20], all of which involved hole sizes in the ~0.1 – 1 mm range and leak rates in the ~ 1 - 10 Pa m

3 s

-1 range.

Aside from noise, another reason that conventional (i.e., electrical) ultrasonic microphones have low sensitivity is that they capture only a small portion (i.e., the low-frequency ‘tail’) of the acoustic power spectrum emitted by a turbulent gas jet, especially for very small holes. In this study, we used a broadband, optomechanical ultrasound sensor to capture the full-range acoustic emissions and show that this offers potential to extend the use of aeroacoustic methods to the detection of smaller holes and lower leak rates than has traditionally been possible, in addition to providing enhanced quantitative information about the leak.

II. Experimental Overview

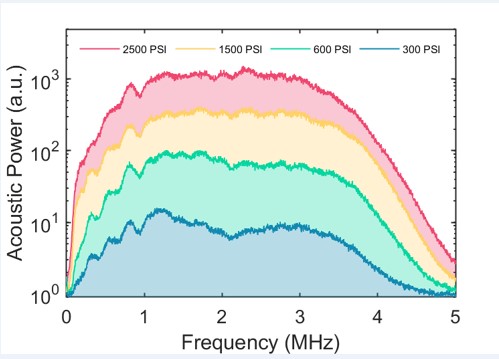

The leak artefacts used in our study are nominally circular, laser-machined holes (Lenox Laser, Inc.) with diameters of ~ 5, 10, 20, 50, and 75 μm, formed at the end of ‘barb’-style gas fittings. In the manufacture of these holes, a steel endplate of the fitting, with thickness of ~ 200 μm, is subjected to high-power laser pulses until a hole of desired size is formed at the bottom of a much larger crater. The approximate size and circular shape of the holes was verified using an optical microscope, as shown for example in

Figure 1(a) for the ~50 μm hole. Additional images are provided in the Supplementary Material (SM) document. The manufacturer specifies a tolerance of +/- 20% for the 5 μm hole and +/- 10% for the others, as indicated by error bars in several plots below.

The barbs were attached to high-pressure tubing and pressurized using either a conventional air compressor for pressures up to ~ 100 psi, or using an air-rifle compressor (Vevor) for pressures up to ~3000 psi. As shown in

Figure 1b,c, the microphone was positioned near the micromachined hole to capture acoustic emissions from the gas jets emanating through the hole.

The optomechanical sensor used to detect air-coupled ultrasound in this work is similar to those we have described in great detail elsewhere [

23]. These sensors are monolithic, curved mirror Fabry-Perot resonators with their flexible upper mirror acting as the mechanical resonator (i.e., essentially as a tiny ‘eardrum’), and separated from a bottom mirror by a partially evacuated cavity. As in our recent work [

24], the sensor chip used here was mounted in a microphone assembly attached to an optical fiber for laser-based readout of the mechanical motion. The particular sensor used to obtain the results below has its first mechanical resonance at ~ 3.7 MHz, and provides a nearly frequency independent noise-equivalent-pressure (NEP) of ~ 50 μPa Hz

-1/2 over the entire ~ 20 kHz to 6 MHz range of interest here. Additional details on the experimental setup, the laser-machined barbs, and the sensor (including its calibration for ultrasound measurement) are provided in the SM document.

IV. Experimental Results

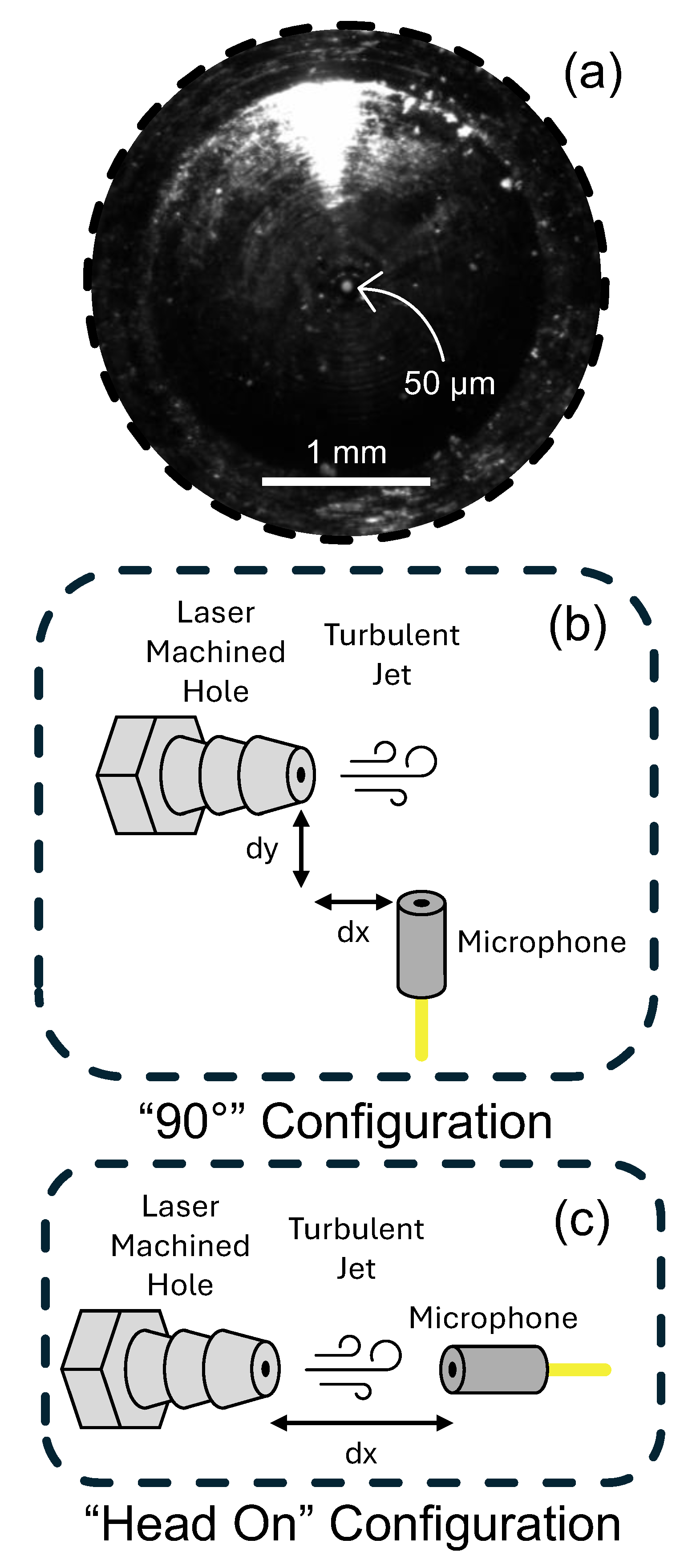

We first studied the acoustic spectra for each of 5 available hole sizes (~ 5, 10, 20, 50, and 75 μm hole diameters), with the internal pressure set to ~ 1000 psi and a hole-to-microphone distance on the order of ~ 1 cm. For each experiment, this spacing was measured with ~ 1 mm precision and was subsequently used to produce an ‘attenuation-corrected’ plot as explained below. As mentioned above, the manufacturer specifies tolerances on the hole diameter, and this uncertainty is indicated through the inclusion of error bars on several of the plots below.

Figure 2(a) shows results for the ~ 75 μm hole, where the red dotted curve is the raw (but calibrated, as explained in the SM document) data reported by the optomechanical microphone. The blue curve is the same measurement, but with the data adjusted on a point-by-point basis to remove the frequency-dependent attenuation of ultrasound by absorption or scattering in air. To estimate this attenuation, we used the simple empirical formula [

33]

α = 1.6 × 10

-12 f [

2], where

f is the acoustic frequency and

α is in units of dB/cm. For example, at 1 cm source-microphone spacing this implies an attenuation of acoustic pressure by a factor of ~ 2× at 2 MHz, ~ 5× at 3 MHz, ~20× at 4 MHz, and ~ 100× at 5 MHz. At MHz frequencies, air-absorption clearly dominates over other sources of attenuation, such as that due to diffraction of spherical waves. Moreover, this rapid scaling of the attenuation is the reason that most air-coupled ultrasound applications are traditionally restricted to frequencies below ~ 2 MHz.

With the frequency-dependent attenuation removed, the adjusted experimental data could be fit very well to the LSS/

F spectrum expected for downstream observation points [

30,

31]. This was true for all 5 hole sizes studied. The analogous case for the~ 10 μm hole is shown in

Figure 2(b), and typical fits for the 5, 20, and 50 μm holes can be found in the SM document. From these fits, the peak of each frequency spectrum was estimated and this data was compared against a Strouhal-relationship scaling curve as shown in

Figure 2(c). For the two largest holes, it was possible to extract the peak frequency with relatively high confidence, and these data points suggested a value of St ~ 0.14. For the 3 smaller holes, much of the spectrum lies above the practical range (i.e., considering air absorption) of the optomechanical sensor, making the estimation of the peak frequency more prone to fitting error. Nevertheless, these fits suggested St ~ 0.1, which is also reasonable given the discussion in Section III.B and elsewhere [

11,

16].

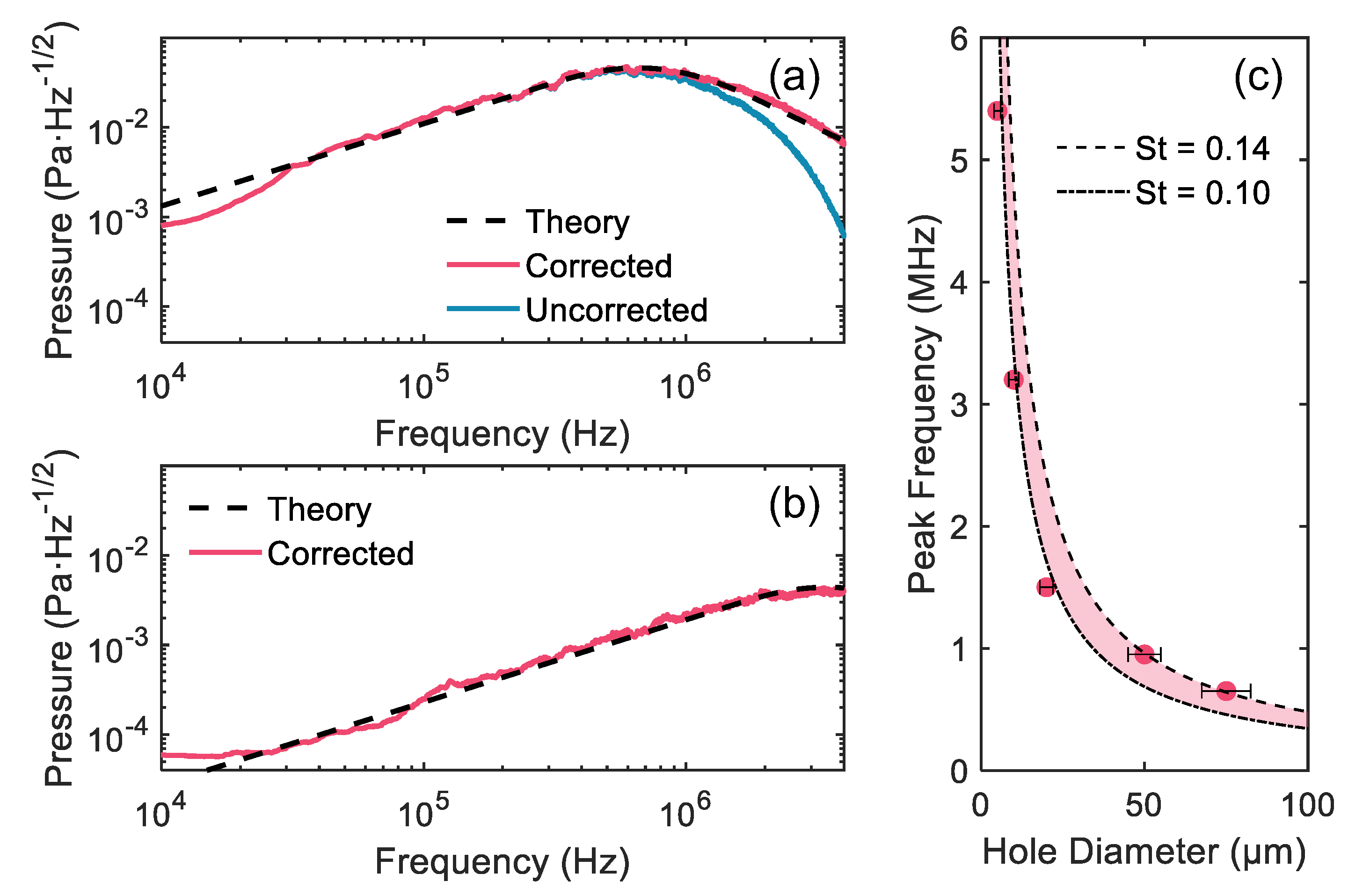

We next consider the variation of the acoustic spectrum and power with internal static pressure for the ~ 5 μm diameter hole. Raw spectra are plotted for various internal pressures (

P1) in

Figure 3(a), and the acoustic power (~ square of acoustic pressure) at an arbitrarily chosen frequency of 2 MHz is plotted versus internal pressure of the barb fitting in

Figure 3(b). This data was collected with ~ 1 cm hole-to-microphone spacing and with the microphone oriented in the downstream direction (i.e., nearly head-on, see

Figure 1). As above, acoustic power spanning the entire ~ 0 – 5 MHz range is measured at close spacing. In keeping with the discussion in Section III.B and assuming choked flow conditions at all internal pressures,

Figure 3(b) verifies that the acoustic power scales approximately with the square of internal pressure for fixed hole diameter. Small deviations from this scaling are likely attributable in part to a large uncertainty in the internal pressure, which was estimated from the analog gauge built into the compressor.

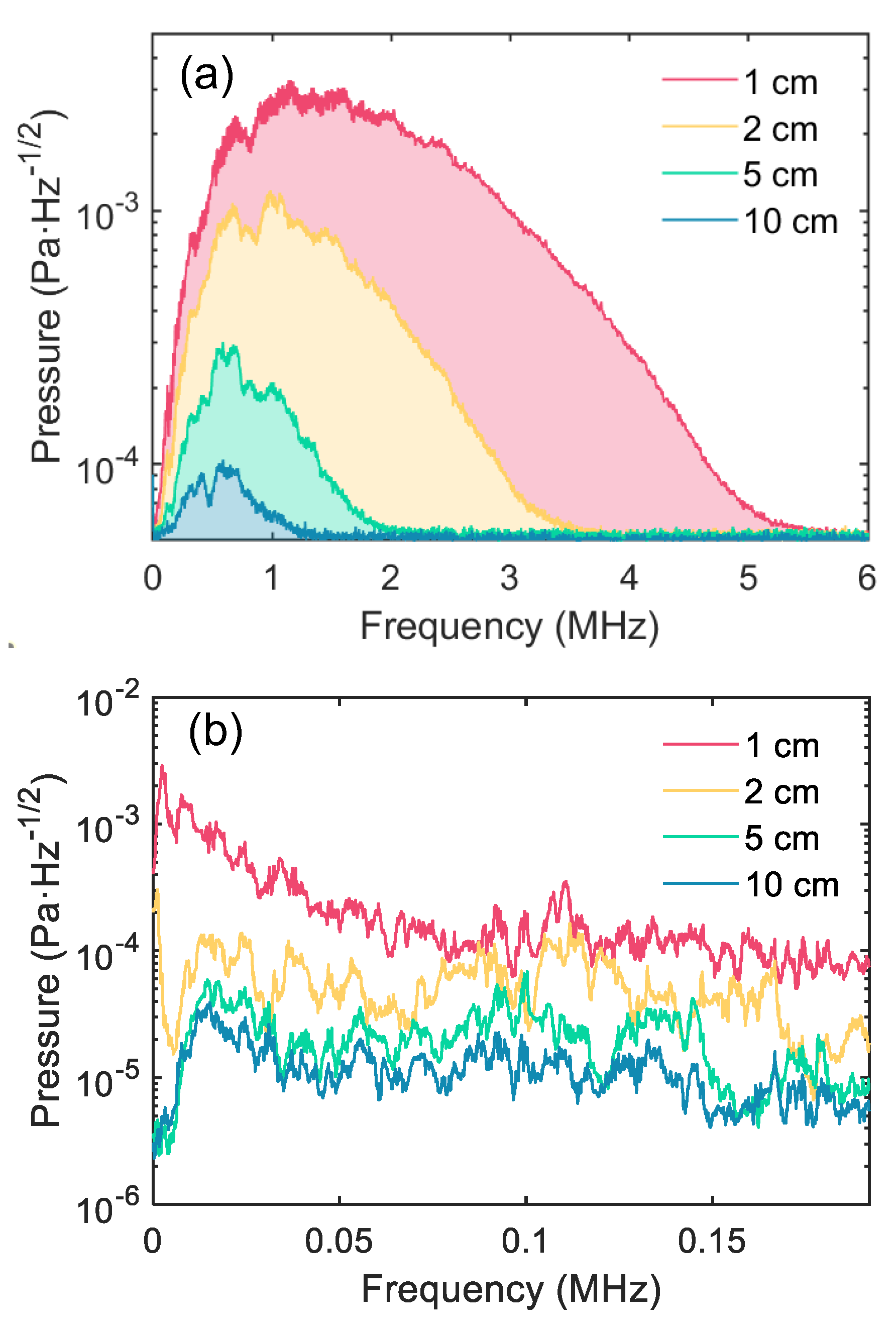

Given the significant impact of air absorption above ~ 2 MHz, it is interesting to consider the dependence of the received aeroacosutical signals on the hole-to-microphone spacing. For this experiment, the ~ 5 μm diameter hole was pressurized to ~ 1000 psi, the optomechanical sensor and a commercial ultrasonic microphone (Dodotronic Ultramic 384KBLE [

34]) were sequentially oriented head-on to the hole, and spectra were collected at various distances. The impact of air absorption is clearly seen in the spectra recorded by the optomechanical sensor shown in

Figure 4(a). As distance is increased, the portion of the aeroacoustic spectrum lying above the sensor’s noise floor (~ 50 μPa/Hz

1/2) shifts progressively downwards. Nevertheless, even at ~ 10 cm distance there is content extending beyond ~ 1 MHz and the peak received energy is above ~ 0.5 MHz.

The commercial microphone has a bandwidth in the ~ 0 – 192 kHz range, and is constructed around a MEMS sensor (Knowles FG-23629 [

35]). Since the microphone manufacturer provides limited specifications regarding noise and sensitivity, we used the self-noise specified by Knowles (NEP ~ 5 μPa/Hz

1/2 [

35]) to scale the spectra in this case, and also made an assumption that the microphone is operating near the mechanical-thermal noise limit [

36]. Regardless of the accuracy of this calibration, the data in

Figure 4(b) illustrate a few interesting points. First, the commercial microphone is also able to detect the sound emitted by this small leak, which is not surprising given that its noise floor is likely somewhat lower than that of the optomechanical sensor used. However, the SNR is limited by the low spectral content of the aeroacoustic spectrum in the range of the electrical microphone. Moreover, the bandwidth of the electrical microphone greatly limits the amount of information that can be extracted from the shape of the received spectrum, in contrast with the optomechanical sensor results shown in

Figure 4(a). Consistent with this, most commercial ultrasonic leak detectors simply rely on sound pressure level in a narrow frequency range (often near ~ 40 kHz) to identify a leak. Proposals for characterizing a leak based on such narrowband measurements exist, but require prior knowledge about the location of the hole [

20] or an ability to vary the internal static pressure of the system [

11]. The more complete picture provided by the optomechanical sensor invokes the possibility of an intelligent ‘sniffer’, which could be guided towards a leak by either a human operator or a robot, and might enable a characterization of the leak rate and hole size and shape based on fusing the data collected at various distances.

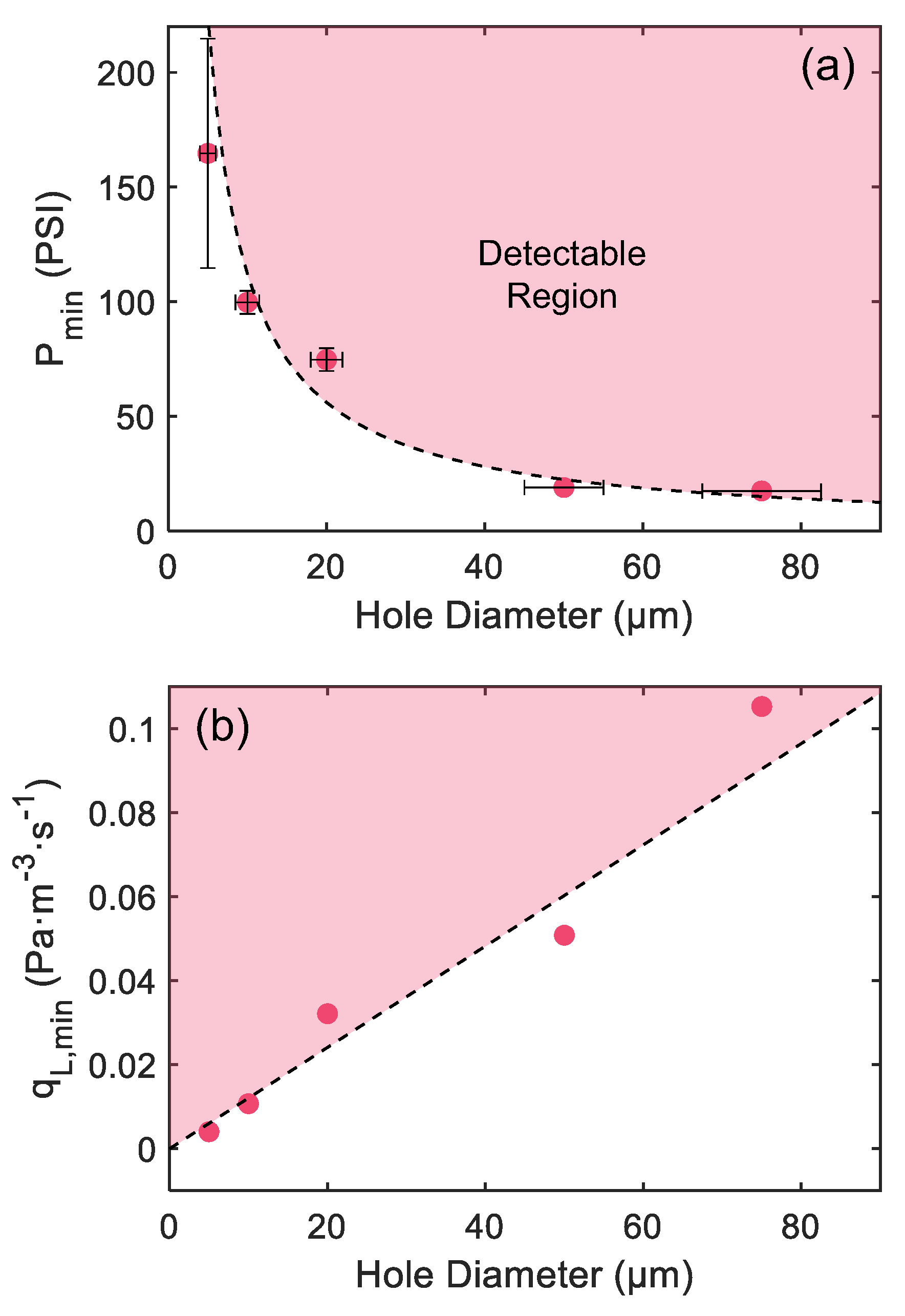

Finally, we considered the minimum internal pressure required to produce measurable acoustic signals for each of the 5 hole sizes studied. For this experiment, the microphone was placed in a nearly head-on orientation and at ~ 1 cm hole-to-microphone spacing. As shown in

Figure 5(a), the experimental results are in good agreement with the predictions of the basic flow model outlined in Section III.A, and furthermore assuming a minimum Reynolds number Re

min = 1000 for the onset of turbulent flow. While the results shown are for the optomechanical sensor, similar results were obtained using the commercial microphone described above. This supports the conclusion that it is the onset of turbulence, rather than other details such as the microphone self-noise, which determines the minimum detectable flow.

These same results are re-plotted in

Figure 5(b), but in this case in terms of the estimated minimum leak rate to produce measurable sound. The predicted minimum leak rate for the largest hole (> 0.1 Pa m

3 s

-1) is entirely consistent with experimental results for similar and larger hole sizes in the literature [

5,

6,

7,

9,

13,

16,

19,

20]. In keeping with the discussion in Section III.B, this minimum leak rate scales downwards in proportion to hole size and approaches ~ 10

-3 Pa m

3 s

-1 for the smallest hole. This is consistent with the minimum (i.e., ‘in principle’) detectable leak rate for aeroacoustic detection that have been stated in some sources [

3,

4,

17], but typically without a complete theoretical justification. The wide bandwidth of the optomechanical sensor used here enables a more complete understanding of these limits.

Some caveats should be added with respect to these estimated minimum leak rates. First, our estimates are based on conservative assumptions regarding the appropriate flow model as discussed in Section III.A and also in the SM document. Second, the results shown were obtained using relatively smooth, round holes, which are likely not the most efficient types of orifices for generating turbulence and thus sound. Real leaks are often shaped more like cracks [

8] or slits [

10] with rough and sharp edges, and it is possible that those orifices would generate turbulence at lower flow rates. Finally, methods for creating sound from laminar jets are known, such as by combining the bubble technique with aeroacoustic detection

6, or by arranging the jetting gas to be incident on some sort of ‘flow mixer’. In light of this, it seems likely that the minimum leak rates estimated from the inherent onset of turbulent flow do not represent an

ultimate limit. Using a combined approach, it seems possible that a sufficiently broadband and sensitive microphone might be capable of detecting leak rates well below 10

3 Pa m

3 s

-1, which would be competitive with chemical and mass spectrometry sniffers. These admittedly speculative points are left for future study.

V. Summary and Conclusions

Using an optomechanical microphone, we have reported on the acoustic emissions of gas jets emanating from orifices as small as ~ 5 μm. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the aeroacoustic, turbulent jet noise spectra for such small orifices. The results were enabled by the high sensitivity and bandwidth of the optomechanical sensor used. The experimental results, such as the dependence of the acoustic intensity and spectrum on the hole size and static pressure differential, show good agreement with predictions for compressible flow and aeroacoustic sound generation from the literature.

Regarding the aeroacoustic detection of gas leaks, our results help to clarify the minimum leak rates that can be feasibly detected. Importantly, we showed that the minimum leak rate, as determined by the onset of turbulence, scales downward in proportion to hole size. This minimum rate was conservatively estimated to be on the order of ~ 10-3 Pa m3 s-1 for the smallest holes studied here. Moreover, as hole size is reduced, the spectral energy shifts increasingly towards higher frequencies and well beyond the range of conventional (electrical) ultrasonic microphones. However, air absorption at MHz frequencies implies that the detection of such high frequencies is only possible for relatively small hole-to-microphone spacing. In the present study, this distance was on the order of < 10 cm.

Nevertheless, the optomechanical sensor exhibits great potential for use as an ‘acoustic sniffer’ with capabilities beyond that of conventional ultrasonic detectors. Notably, electrical microphones capture only a small portion (the low frequency ‘tail’) of the aeroacoustic spectrum emitted by small leaks, and are thus typically limited to reporting only the relative sound intensity levels. Moreover, the portion of the spectrum that they detect is often polluted by other ultrasonic noise sources in a typical industrial environment. The more complete picture provided by the optomechanical microphone, perhaps combined with machine learning techniques, could enable the detection of smaller leaks, and possibly the quantification of details such as hole size and shape and leak rate, based on the spatial-spectral dependence of the aeroacoustic noise spectrum. We hope to explore these possibilities in future work.