1. Introduction

Expanding and financing reliable electricity access in low- and middle-income countries is a central concern of international energy policy. The International Energy Agency (IEA), for example, routinely publishes reminders that hundreds of millions of people still lack access to electricity, most notably in countries in sub-Saharan Africa [

1]. Similar reports celebrate the continued expansion of energy access through the increased adoption of off-grid solar energy technology, demonstrated by strong sales of solar equipment in African countries [

2]. Yet such research tends to ignore an equally significant development: the rumble of diesel generators that often accompanies solar photovoltaic (PV) panel installations. (A note on generator fuel types: we acknowledge that small generators (typically those less with a real power of less than 10 kW) tend to operate on gasoline rather than diesel. However, while differences in fuel type may play a role in policy and regulatory design such as emissions regulations, the techno-political implications of both fuels are similar: noise, price, costs, et cetera. We thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to this distinction.)

The electricity source of last resort, diesel generators are to be found in many communities around the world that are unconnected to the grid. Generators are particularly important in countries where access to the grid is limited, as their ability to transform diesel into electricity enables other ‘modern’ amenities, including lighting, cooling and information technology in off-grid areas. In 2019, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimated that backup generators provided 9 percent of total electricity generation in sub-Saharan Africa [

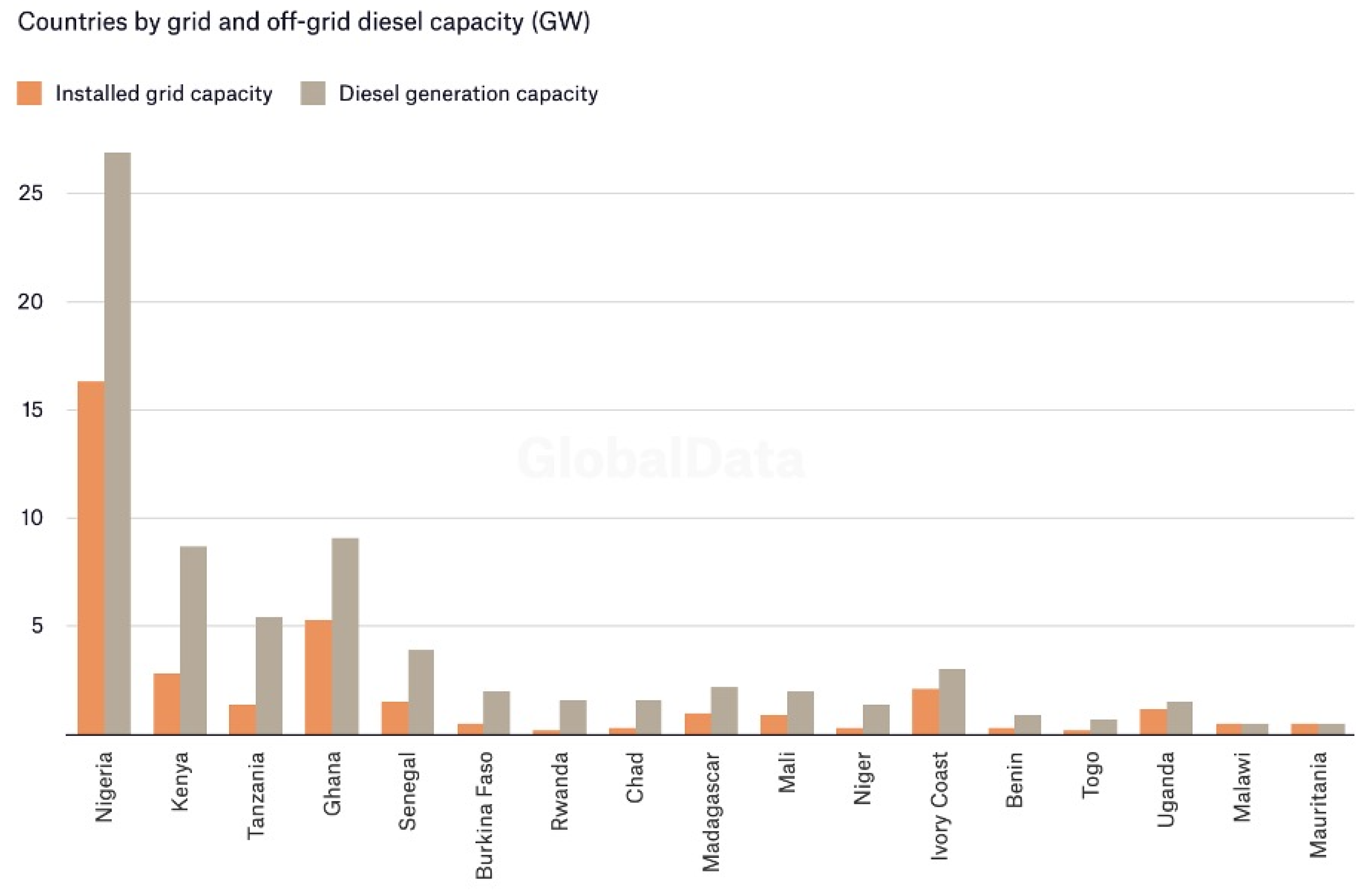

3]. Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy, estimated that by 2022, seventeen African countries had installed more diesel generation capacity than generation linked to the grid (

Figure 1), and that thirty-nine African countries had installed a total of 100 GW of diesel generation capacity [

4].

Importantly, however, the growing demand for generators is not limited to low- and middle-income countries. Armed conflict and extreme weather events have frayed the wires of electricity grids in wealthier countries [

1]. In Ukraine, diesel generators were in such high demand following the 2022 Russian invasion that generator imports were represented separately in national accounts [

2]. In the United States, makers of backup generators describe a “burst in new business" thanks to the intensification of the hurricane season [

3]. The newfound awareness of the fragility of the central grid has also led to increases in so-called ‘ancillary services’ within national grid systems, where grid service operators in countries such as the United Kingdom habitually award contingency contracts to generator companies to provide rapid backup supply [

4].

The increasing ubiquity of the diesel generator demands a careful reconsideration of the energy transition, particularly in terms of the technological, material and political-economic limitations of the zero-carbon imaginary [

5]. (Our thanks to an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this point.) Not only does total generator capacity far exceed that of off-grid solar energy [

11], but our research also suggests that generators play an important role in enabling the adoption of off-grid renewables by providing backup power on rainy days. The rise of the generator means that the energy transition in many countries incorporates not only renewable forms but also decentralised fossil fuel generation: in other words, that the expansion of off-grid solar PV is often inextricably linked to diesel generator technology, which solves the technical problems of variability and intermittency inherent in solar PV. After all, the diesel generator is not only a source of electricity, but diesel is a store of energy that can be converted to electricity at any time. Although China’s recent industrialisation of solar PV and lithium battery production has enabled both to be marketed on a global scale at greatly reduced costs [

6], hydrocarbons including diesel remain a more affordable and often more reliable medium for energy storage [

7].

This article’s central aim is to account for the profound success of the diesel generator at this historical juncture. We argue that there are several reasons for the dominance of the polluting but successful generator: at a material level, the generator’s reliability, affordability, modular and portable nature and the opportunities for rent-seeking it offers; at a structural level, the increased fragility of existing grids due to armed conflict and disaster, and the confluence of post-grid imaginaries with the highly limited success of the neoliberal unbundling agenda, the supposed efficacy of privatisation narratives and the collapse of the centralised grid in poorer countries [

8,

9]. The generator is the emblem of this fragmentation, but also ends up re-configuring the everyday political economy of energy access. Having established the reasons for the diesel generator’s success, we conclude by engaging in debates surrounding the energy transition. In particular, we argue that diesel generators are essential to the expansion of renewable microgrids, suggesting that changes in the global provision of energy typically involve addition rather than transition, a point already made many times [

10,

11,

12]. However, instead of despairing at the inexorable advance of diesel generators, we suggest that a clear-eyed reading of hybridised energy systems invites an appreciation for the interlinkages that underpin them.

2. Generators: Taken-for-Granted Yet Functional Technologies

This section first reviews the available literature on the diesel generator, arguing that the diesel generator is virtually always understood as a background technology with little focus on the social or political function of the generator itself. The section then tries to fill this gap by providing an overview of the history of the diesel generator, arguing that the simplicity of generator technology and its ability to provide electricity in the absence of other sources has facilitated its mass adoption. We chart the growth of this ancillary source of electricity provision, examining how it has become a key form of energy provision both in contexts that lack grid access and in those where electricity access is universal.

Although the diesel generator figures in much scholarship, including in the pages of

Energy Research and Social Science, it is almost invariably in passing: as a technical device operating in the background and devoid of any political or social dimensions. Generators figure in a variety of empirical contexts, such as in Indigenous areas of Brazil [

13], Nigeria [

14,

15], South Sudan [

16], Indigenous communities in northern Canada [

17], Liberia [

18], Ghana [

19], Spain [

20], and Lebanon [

21,

22], among others.

While a well-developed body of literature examines the economic and technical feasibility of diesel generators in a variety of settings [

23,

24], little research exists on the anthropology of the generator [

25], while research on the global political economy of energy mentions generators only in passing [

26,

27,

28]. This suggests an epistemological blind spot in the literature, which juxtaposes fossil-fuelled centralised grids with the spectre of decentralised renewable energy while overlooking the spread of decentralised fossil fuel infrastructure. Given this lacuna, we want to suggest that decentralised diesel generation has played a central – but under-examined – role in the global expansion of electricity access. Renewable energy access is accompanied and enabled in many cases by diesel generators, ensuring the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure by other means. In several national contexts, the unregulated governance of generators raises important questions about the social, economic and political advantages of the use of generators, over and above their environmental impacts [

3].

The generator is, in fact, an old technical innovation. The origins of the generator may be traced to the middle of the 19th century and the confluence of two innovations that occurred within a few years of one another: the development of the electromagnet by the British engineer Charles Parsons and the two-stroke internal combustion engine by the German engineer Nicolas Otto. Parsons is credited with having invented the first steam turbine in 1884 by distributing several turbines along an axis to remove the risk of damaging a single turbine [

29]. Otto’s development of the internal combustion engine would eventually lead to the mass production of small diesel generators produced by auto manufacturers. One hundred years later, generators would become indispensable to the provision of electricity in manifold international contexts, whether off-grid or on-grid. Generators proved enormously adaptable to specific power demands, capable of producing a few kilowatts or many megawatts. The hyper-mobile nature of generators meant that they could be rapidly deployed to virtually any location ready to use, making them a highly versatile source of electricity: today, generators power ninety per cent of freight ships globally as well as applications as diverse as construction, automotive and military equipment [

29].

As indicated above, generators have become the dominant energy technology in places with weak or absent grids, including Lebanon, Nigeria, Iraq, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Generator usage in these contexts is driven by several factors, including the failure of grid reform policies, poor macroeconomic conditions driven by subsidies on imported fuel and weak state institutions. In countries such as Lebanon, residents perceive the political and economic interests of generator operators to be a hindrance to electricity sector reform. In other countries, diesel generator installation has been even more prolific. In the Nigerian context, Daniel Jordan Smith has described the existence of generator ‘mafias’ in areas such as Umuahia, where locals are suspicious that government officials are implicated in the private ownership of diesel generator networks [

30]. Such claims are impossible to verify conclusively, as is the case in Lebanon. Mafia or not, the business works somewhat differently to the model in Lebanon: households typically own their own small generator, which they purchase from a distributor who may or may not be part of a local or national cartel. (In the Lebanese context, the category `mafia’ is contentious. Despite the prevalence of the term in national discourse, researchers, academics and generator owners themselves frequently point to the cartel of fuel import companies who supply the country with its requisite hydrocarbons as the `real’ energy mafia. The framing of local electricity suppliers as a mafia risks obscuring not only the diversity of governance structures in the generator sector but also distracting attention from the highly lucrative and rent-seeking behaviours of Lebanon’s petroleum importing companies.) In Iraq, Ali Al Wakeel’s analysis has shown that generators are typically owned by private entrepreneurs or municipal authorities, who charge various tariffs depending on the time of year and the number of hours available [

31], while Abeer El-Eryani has shown how, in Yemen, diesel generators have become an essential part of the war economy, with rents on imported diesel a central revenue source for the Ansar Allah administration [

32]. Diesel generators have also been an important part of electrifying rural areas in Afghanistan and provide significant back up capacity in India [

33,

34].

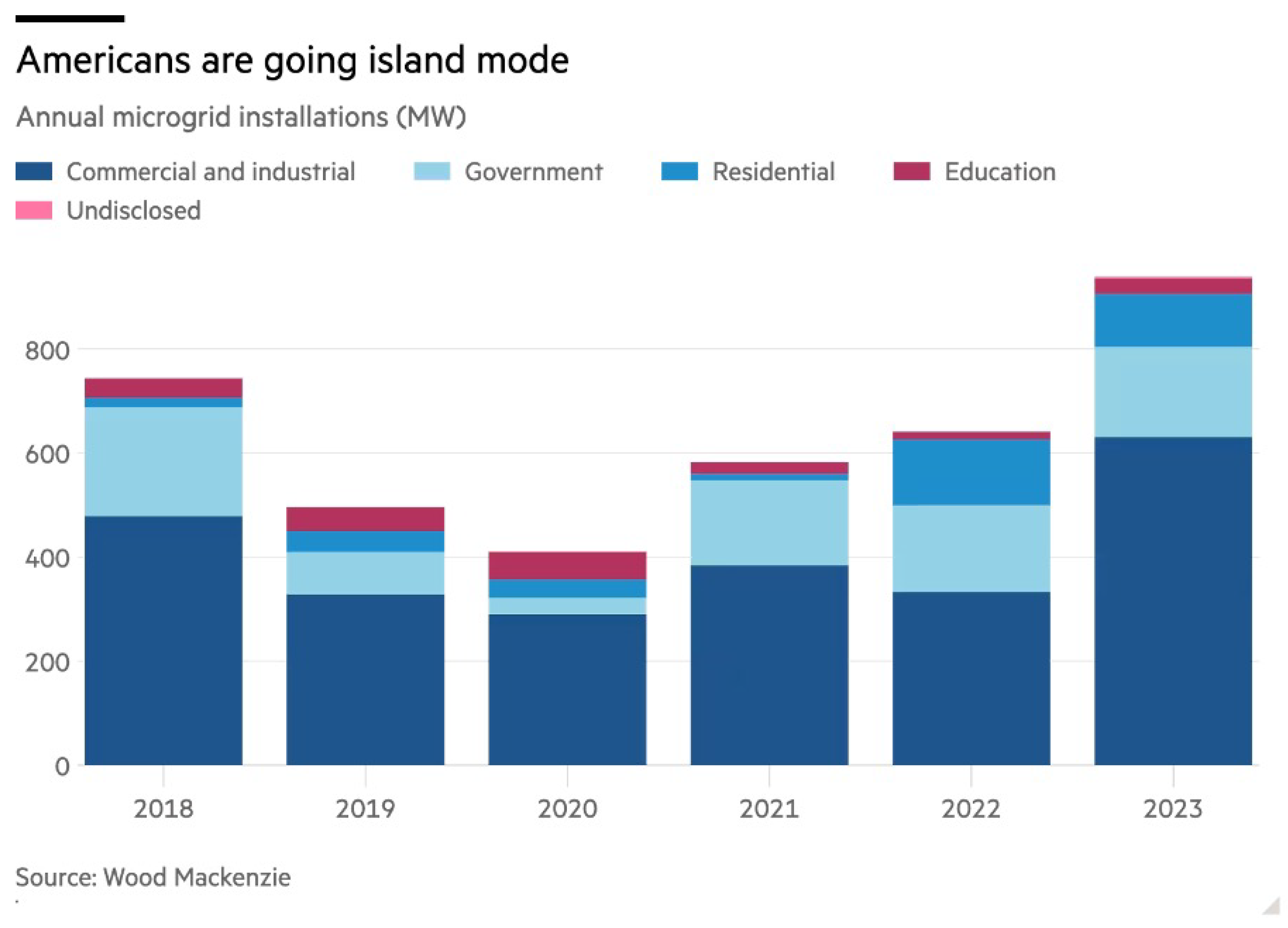

Importantly, it is not only poorer countries that exhibit growing reliance on diesel generators, but also wealthier ones including the UK and the USA. In these countries, diesel generation demand is being driven by multiple factors, including the perceived need to provide baseline capacity for increased renewables on the national electricity grid as well as a growing tendency by households in the United States and Europe to protect themselves from grid outages by purchasing diesel generators. Generator markets in wealthier countries are steadily expanding and have become interesting investment opportunities for large financial institutions. In the United States, where power outages are estimated to occur more frequently than in any other developed country [

35] and where power outages increased more than tenfold between the 1980s and 2012 [

42], businesses and households have steadily increased their purchases of diesel generators, which, although not always, frequently use diesel generators to complement solar PV and batteries (

Figure 2) [

36]. Increasing purchases of such microgrids is particularly noticeable in states such as California, which have been exposed to blackouts surrounding forest fires. The growing microgrid market has attracted the interest of multinational oil companies, utilities, private equity and commercial lenders, for whom the above-market, stable returns offered by microgrids constitute a lucrative investment proposition [

44]. And although generators are everywhere today, their manufacturers are not. The global generator market is dominated by several European and North American companies, including Caterpillar, Cummins, Generac, Kohler, Doosan and Rolls-Royce [

45].

Recent shocks in the global political economy have threatened to reduce the attractiveness of generators, and yet they continue to be relied upon. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the dramatic increase in global diesel prices and the removal of diesel subsidies have significantly increased the operating costs of diesel generators and increased the competitiveness of solar PV. Examining the case of Lebanon, where grid collapse and diesel shortages have led to a rapid adoption of off-grid solar, highlights the continued importance of diesel generators. While households in Lebanon have proven willing and capable of adapting their energy usage to the sun’s rhythm, community scale, or industrial solar operations are less capable of doing so. Such systems therefore tend to exhibit ‘hybridisation’, where they rely on a combination of solar PV and backup diesel generators; scholars have already begun to develop the idea of hybridised energy systems in a variety of contexts, including Lebanon and South Africa [

37,

38,

47]. In other words, since a truly decentralised energy transition cannot balance the irregularity of solar power through a large grid, such systems continue to rely on diesel generators to provide rainy-day backup.

3. Reading the Generator Through Science and Technology Studies

This section presents theoretical perspectives from Science and Technology Studies (STS), whose concern with the seemingly mundane offers a chance to explore the links between the ostensibly boring diesel generator and its major role in contemporary distributed electricity production [

39,

40,

41]. An STS lens lends itself to interpreting the diesel generator as a sociotechnical device that mediates and co-produces social, political and environmental relations beyond the reach of the grid. [

42]. Through their ability to transform the energy stored in fossil fuels into electricity – the medium of power that sustains modern life – they are crucial to weaving marginal places into the global networks of information [

43]. STS’s propensity to recognize the interplay between social, technological and environmental factors thus enables us to re-interpret the mundane generator as a controversial technology sitting at the nexus of some of humanity’s most pressing questions, from the political economy of centralised infrastructures to the urgency of improving electricity access, as well as the need to adapt to an increasingly volatile politics and unstable climate [

44,

45].

As technical devices, diesel generators encapsulate two sides of modernity: the polluting world of fossil power and the clean world of electrified modernity. Fossil power has played a central role in enabling the modern condition: politically, economically and environmentally[

46]. This energy regime is increasingly polluting the world we inhabit and wreaking political havoc where its resources are to be found [

47]. Infrastructures are not just technological, but also poetic [

48]: the irritating noises and smells produced by generators not only reflect infrastructural breakdown, but also conjure an image of the failure of social and political institutions tasked with providing electricity. As such, the diesel-generator constitutes a sociotechnical symbol – to use Larkin’s term, a poetics – of the failure of the modern nation state itself. At the same time, generators provide the figurative lifeblood of modernity, their electricity enabling the maintenance of contemporary life, from light at night to air-conditioning and telecommunication.

The stability and reliability of electricity grids have recently come under pressure from neoliberal policies, environmental disaster, and emerging technopolitical visions about decentralised renewable energy. Joanne Nucho has coined the term “post-grid imaginaries” to capture the growing frailty of the grid as both an infrastructure as well as an idea [

49]. Importantly, post-grid imaginaries present utopian and dystopian visions of the grid. In the dystopian vision, grids are critical infrastructures crumbling under the combination of neoliberal spending cuts and climate change-induced natural disasters. From a more positive front, post-grid imaginaries encapsulate the emancipatory potential of local and decentralised energy systems. In this reading, central grids are not imagined as the material instantiation of a caring government, but rather as the tentacles of an increasingly authoritarian (surveillance) state [

50].

While their rattling noise and smelly exhaust fumes often make them controversial in their immediate surroundings, generators remain a mundane energy technology and have received less attention than their glitzier cousins: solar, wind or even fusion. David Edgerton’s concept of the ‘shock of the old’ can be usefully applied here: those fantasising about the silent revolution of decentralised renewables are in for a shock, since they must also deal with the crude workings of a diesel generator to back them up during long nights and rainy days [

51]. Even though - or perhaps because - the diesel generator has been a stable technology for the last 70 years, it continues to play a vital role in converting the power stored in crude fossil fuels into modernity’s most decisive medium of power.

4. The Failure of Developmental Imaginaries

The fact that generators are there when grids fail to emerge must be situated within broader developments in global electricity governance. In part, the emergence of the generator is a reflection of failed efforts to unbundle and deregulate grids during the period between the 1990s and the 2020s, when state-owned utilities, the product of socialist techno-politics in post-colonial societies, came under increasing pressure from international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to ‘unbundle’ their generation, distribution and retail assets, which were to be privatised and managed by independent regulators. Policies of unbundling and privatisation in national electricity sectors around the world, an approach known as the `standard model’, envisioned independent power producers (IPPs) competing against one another to sell power into the grid. Creating competitive electricity markets, it was assumed, would drive down the cost of electricity, expand grid access, reduce public sector spending, promote private investment, and achieve various other successes notionally associated with privatisation.

However, the results of implementing the standard model have been mixed. In Nigeria, for example, generation and distribution capacity has increased significantly, but material challenges including poorly-maintained existing transmission infrastructure, a lack of reliable gas supply to thermal power plants and an ineffective independent regulator have prevented the full implementation of the standard model [

52,

53]. In something of a confession, the World Bank has since indicated that limited electricity sector reform may be attributed to the standard model’s failure to account for context-specific political economy factors [

54]. Subsequently, the World Bank openly acknowledged the failure of these unbundling processes in a 2020 report,

Rethinking Power Sector Reform in the Developing World, in which it conceded the authors conceded that the private reforms insisted upon were often unsuccessful and not always appropriate [65].

Against the backdrop of unreliable electricity supply, households have opted to purchase diesel generators to meet their domestic electricity consumption needs [

30]. In Lebanon, electricity sector reform has proved too politically controversial to implement despite legislation introduced in the 2000s. As a consequence, the Lebanese state-owned vertically integrated electricity company continues to govern the grid to varying degrees of success, with diesel generators assuming an increasingly large proportion of residential and commercial electricity demand [

21,66].

Also crucial to the generator’s success has been the slow deployment of so-called climate finance to raise the capital necessary to achieve energy transitions in countries with limited fiscal capacity and which face the rising cost of tackling the effects of climate change. With the arbitrary figure of USD 100 billion announced at the Copenhagen COP in 2008 only recently attained, poorer countries have historically struggled to attract the capital necessary to invest in grid, renewable and storage infrastructure. All of this must be understood within the broader context of a shift in development finance ideology, which Daniela Gabor has characterised as the shift from the Washington Consensus of the 1990s to a ‘Wall Street Consensus’ in which infrastructure is understood to be a private asset to be de-risked by public finance [

55]. Relatedly, Brett Christophers has pointed to the failed efforts to privatise national energy infrastructure pursued by international development institutions, and to the prolific profit-making opportunities inherent in fossil fuel infrastructure relative to renewable energy [

56]. This profit-making dynamic is no less present in diesel generators as it is in large-scale fossil-fuel energy generation and constitutes an important factor in the incentive to build out generator capacity in several countries where generators prevail. These policies have led to actors including the World Bank promoting solar-based technologies that promise to provide electricity off-grid, avoiding the high costs of grid expansion [69].

5. Discussion: Friend or Foe?

Thus far, we have argued that diesel generators play an important yet often neglected role in enabling the spread of decentralised renewable energy solutions. We now want to discuss the implications of the diesel generator for energy scholarship as well as proponents of locally-led energy transitions. We can do so by examining the solar microgrid, arguably the sociotechnical totem of energy democracy, or, to use Joanne Nucho’s terminology, a utopian ‘post-grid imaginary’ [

49].

Like a centralised grid, a solar microgrid provides electricity to households and businesses that are connected to it. The main difference is that of scale. Sometimes also referred to as a village grid, or mini grid, such systems connect a local community to a local source of (solar) power. Proponents of solar microgrids argue that they offer both a cleaner and significantly cheaper pathway to electricity access in the global south [70]. Besides such economic and ecological advantages, the idea of decentralised renewable energy has also captured the political imagination. Advocates of so-called energy democracy argue that empowering local communities to govern their own, clean energy infrastructure has positive political effects. Electricity produced by the community for the community, it is argued, increases accountability, efficiency and resilience from external shocks [71].

While we agree with the idea that solar microgrids can emancipate communities from polluting and less reliable centralised grids, we would also suggest that the glossy presentations of and stories about such systems tend to overlook the fact that diesel generators remain central to their operation. This is the case in Jabboule, a town in Lebanon that is home to one of Lebanon’s most advanced solar microgrids. Installed on the grounds of the local Maronite monastery, the system is state of the art, operating a football-field-sized 1 MW solar array, a container full of lithium batteries, an extensive medium voltage network, as well as hundreds of smart metres, that enable a cheap daytime tariff and a more expensive nighttime tariff. The less mentioned and somewhat dirty, but necessary, part of this system is a large diesel generator. It remains necessary to provide electricity on cloudy days, where the solar panels cannot pick up enough of the sun’s rays, as well as during the early hours of the day, when the battery has run out. The intermittency of solar power, combined with the high cost of electricity storage, necessitates the presence of a diesel generator that can pick up the ‘slack’ when the sun is not available.

The proliferation of solar mini-grids and microgrids in rural communities, without access to a functional grid, thus continues to depend on diesel and the dirty black box that can transform it into electricity at the push of a button. As extreme a case as the Lebanese energy landscape has been in the last five years, such developments are not unique to this small country in western Asia. Failing electricity grids, diesel shortages and price hikes have led to similar cases of rapid solarisation in countries including Yemen [72], Pakistan [73] and Nigeria [

57]. In both Pakistan and Nigeria, for example, the dual trend of unreliable central electricity grids and starkly increasing diesel prices has contributed to the growing adoption of solar PV as the cheapest source of electricity [

57,73]. However, the nightly and weather related interruptions, combined with the high cost of electricity storage, still necessitate fossil-powered backup systems, ensure constant demand for diesel generators.

6. Conclusion

The core question we want to pose in this article is: what are energy scholars to make of the enduring presence of fossil fuel electricity generation in decentralised renewable energy systems? A preliminary answer is that it depends on the scale of the generator. Moving just a few kilometres south of the village of Baaloul in Lebanon, it is possible to visit another ‘hybrid’ microgrid. Here, however, the energy mix is much more skewed towards the generator’s fossil power. Two 600 kVa machines, (capable of producing about 1,000 kW of power) stand opposite a meagre 150 solar panels, contributing at best some 80 kW of solar power. In this scenario, the village’s electricity remains largely fossil-based, with only some 20 percent of the power coming from the sun.

As we have tried to show, energy discourse emphasising the need to phase out coal and fossil gas infrastructure has tended to exhibit an epistemological bias towards centralised energy generation while ignoring the blossoming landscape of decentralised fossil fuel infrastructure in the form of diesel and gasoline generators. These generators have thrived in recent years thanks to several factors: the failure of the unbundling agenda to translate into expanded and affordable energy access in many countries, decaying grid infrastructure and the inability of electricity utilities to implement effective cost recovery electricity tariffs. The rise of the generator is thus linked to broader questions of state capacity and energy imaginaries that have understood the state as central to driving shifts in patterns of energy consumption and the reshaping of energy infrastructure writ large. Our article has tried to demonstrate that, in the absence of a strong centralised (state) grid, diesel generators have flourished. Although the manifold health and economic burdens that invariably accompany these generators have been well documented, generators have continued to expand as a primary source of electricity in many communities that lack connections to the centralised grid or the capital necessary to purchase renewable energy generation.

Our article also complicates the notion of a utopian post-grid imaginary that has gained currency in academic research and public discourse [

49]. As we have shown, decentralised energy provision frequently, if not always, involves continued reliance on back-up diesel generators for ‘rainy’ days. This reliance is not limited to lower-income countries, but also extends to wealthy countries such as the United Kingdom where generation capacity is awarded ancillary contracts. If, as we have tried to show, renewable energy transitions depend significantly on fossil generation capacity, ‘hybridity’ would seem to be the de facto outcome in many instances [

38].

With international `climate finance’ now explicitly seeking to bring an end to coal generation through mechanisms such as the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JET-Ps), it is worth asking whether diesel generators benefit from this attention on centralised, `legacy’ infrastructure. As spontaneous energy transitions are in motion across the world, generators serve not only as back-up but as enablers of the energy transition. This is particularly true in contexts affected by fragility and conflict, where communities avoid investing in expensive solar infrastructure by opting for generator subscriptions with higher variable costs and greater limitations on capacity. If the policy objective is to avoid the proliferation of new forms of fossil fuel infrastructure, the diesel generator must be contended with as a formidable and durable form of decentralised fossil fuel infrastructure.

The uncertainty caused by political crises and extreme weather events have presented an existential challenge to the stability and expansion of centralised electrical grids. In countries such as Lebanon, Nigeria, or Pakistan, large scale energy transition projects are quite literally ‘grid-locked’, forcing households and businesses to procure alternative, off-grid solutions. Small scale and decentralised solar energy are thus increasingly seen as a more efficient pathway to promote the dual goals of improving energy access and reducing CO2 emissions. As we have argued, the mundane technology of the diesel generator will play an unexpectedly large role in facilitating local and small scale energy transitions: for those promoting local solutions such as village and microgrids as a means of leap-frogging over the inertia of large, centralised grids, the rumbling diesel generator will likely remain a necessary companion for some time to come.

Given the dominance of the diesel generator in so many settings, it is our conviction that future scholarship should investigate not only the technical supporting role of diesel generators in local or national energy generation but, as we have tried to argue, the specific political economy engendered by the materiality of diesel generators. Creative methodologies may need to be developed to conduct such research. Our own fieldwork experience suggests that researchers who focus on the political economy of the diesel generator may encounter challenges typical of research in informal settings, including access to high-quality, publicly available and verifiable data, recruiting interview participants, and illegality, among other difficulties. Such challenges are not insurmountable [

58], although researchers of the diesel generator may have to rely on qualitative research methods to generate empirical findings [

59].

The need to provide empirical and theoretical substantiation for the new reality of diesel generators gains additional significance in the broader normative context of achieving energy and social justice. While this article has at times taken a light-hearted approach, it remains the case that generators can and do cause significant environmental, financial and political hardship among the populations who use them, particularly in cases where generators are owned and operated by private, rent-seeking actors [

3,66]. As urban populations increase, so too will demand for electricity; in the absence of alternative solutions, this electricity may well be provided by diesel generators, meaning that urban populations will become increasingly exposed to the immensely harmful emissions produced by diesel generators. Diesel generators have been estimated to produce around forty toxic air contaminants [

60], which contribute to increased rates of non-communicable disease including lung cancer, asthma and rhinitis [

60,

61].

Finally, our article thrusts the diesel generator into the debate surrounding the nature of the energy `transition’ and the question of whether it is in fact appropriate to speak of an energy transition at all. The historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz has recently argued that, given human societies’ tendency to use larger, not smaller, quantities of previously-exploited energy sources when exploiting new energy sources, the term `accumulation’ is more helpful than `transition’ [

12,

62,

63]. The success of the diesel generator only reinforces the impression of an almighty imbrication of renewable and non-renewable energy sources. In line with Fressoz and others who have made similar arguments [

10,

11], we do not deny the urgent need for the mass adoption of renewable energy forms; more solar energy is required, not less. Yet a clear-eyed approach to the installation of renewable energy is necessary, if only to counter the discursive strategies of renewable energy opponents that centre around its unreliability [

64]. Acknowledging the role of the diesel generator in the expansion of decentralised renewable energy requires us to examine, however reluctantly at times, the interlinkages necessary to secure electricity access.

References

- Bakke, G.A. The Grid: The Fraying Wires between Americans and Our Energy Future; Bloomsbury USA.

- Rathbone, J.P. Scenes from Ukraine: The Generator Anthem.

- Aeppel, T. US Maker of Generators Sees Demand Surge in Wake of Hurricanes.

- Espinoza, J.; Pfeifer, S. Sembcorp Swoops for UK Power Reserve.

- Tozer, L.; Klenk, N. Discourses of Carbon Neutrality and Imaginaries of Urban Futures. 35, 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Nahm, J. Testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

- Buenfil Román, V.; Espadas Baños, G.A.; Quej Solís, C.A.; Flota-Bañuelos, M.I.; Rivero, M.; Escalante Soberanis, M.A. Comparative Study on the Cost of Hybrid Energy and Energy Storage Systems in Remote Rural Communities near Yucatan, Mexico. 308, 118334. [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Hook, A.; Sovacool, B.K. Power Struggles: Governing Renewable Electricity in a Time of Technological Disruption. 118, 93–105. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Divergent Paths to a Common Goal? An Overview of Challenges to Electricity Sector Reform in Developing versus Developed Countries.

- Melosi, M. Energy Transitions in Historical Perspective. In Energy and Culture: Perspectives on the Power to Work; Routledge; pp. 3–18.

- York, R.; Bell, S.E. Energy Transitions or Additions?: Why a Transition from Fossil Fuels Requires More than the Growth of Renewable Energy. 51, 40–43.

- Fressoz, J.B. Sans Transition: Une Nouvelle Histoire de l’énergie; Seuil.

- Lembi, R.; Lopez, M.C.; Ramos, K.N.; Johansen, I.C. ; family=Silva, given=Lázaro João Santana, p.u.; Santos, M.R.P., Lacerda, G.Y.C., Neuls, G.S., Eds.; Moran, E. Towards Energy Justice and Energy Sovereignty: Participatory Co-Design of off-Grid Systems in the Brazilian Amazon. 119, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, R.; Strachan, P.A.; Singh, A.; Von Malmborg, F. Exploring the Dynamics of Socio-Technical Transitions: Advancing Grid-Connected Wind and Solar Energy Adoption in Nigeria. 119, 103850. [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Watkins, M.; Iwuamadi, C.K.; Ibrahim, J. Breaking the Cycle of Corruption in Nigeria’s Electricity Sector: Off-grid Solutions for Local Enterprises. 101, 103130. [CrossRef]

- Thiak, S.; Hira, A. Strategic Options for Building a New Electricity Grid in South Sudan: The Challenges of a New Post-Conflict Nation. 109, 103417. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N.; Martin, D.; Wood, B.; Hudson, A.; Battcock, A.; Atkins, T.; Oxford, K. Is ‘Eliminating’ Remote Diesel-Generation Just? Inuit Energy, Power, and Resistance in off-Grid Communities of NunatuKavut. 118, 103739. [CrossRef]

- Innis, P.G.; family=Assche, given=Kristof, p.u. Permanent Incompleteness: Slow Electricity Roll-out, Infrastructure Practices and Strategy Formation in Monrovia, Liberia. 99, 103056. [CrossRef]

- Eledi Kuusaana, J.A.; Monstadt, J.; Smith, S. Practicing Urban Resilience to Electricity Service Disruption in Accra, Ghana. 95, 102885. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rivas, U.; Tirado-Herrero, S.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Martínez-Crespo, J. Disconnected, yet in the Spotlight: Emergency Research on Extreme Energy Poverty in the Cañada Real Informal Settlement, Spain. 102, 103182. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; McCulloch, N.; Al-Masri, M.; Ayoub, M. From Dysfunctional to Functional Corruption: The Politics of Decentralized Electricity Provision in Lebanon. 86, 102399. [CrossRef]

- Abi Ghanem, D. , Insights from an Assemblage Perspective for a (Better) Understanding of Energy Transitions. In Dilemmas of Energy Transitions in the Global South, 1 ed.; Routledge; pp. 18–38. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.L.; Hoffmann, C.A.A. Replacing Diesel by Solar in the Amazon: Short-Term Economic Feasibility of PV-diesel Hybrid Systems. 32, 881–898.

- Mahmoud, M.M.; Ibrik, I.H. Techno-Economic Feasibility of Energy Supply of Remote Villages in Palestine by PV-systems, Diesel Generators and Electric Grid. 10, 128–138.

- Abdul-Salam, Y.; Phimister, E. The Politico-Economics of Electricity Planning in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Ghana. 88, 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Lawrence, A.; Watson, M. New Directions in the International Political Economy of Energy. 26, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Newell, P. Trasformismo or Transformation? The Global Political Economy of Energy Transitions. 26, 25–48. [CrossRef]

- Newell, P. Power Shift: The Global Political Economy of Energy Transitions; Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Smil, V. Creating the Twentieth Century : Technical Innovations of 1867-1914 and Their Lasting Impact; Oxford University Press.

- Smith, D.J. Every Household Its Own Government: Improvised Infrastructure, Entrepreneurial Citizens, and the State in Nigeria; Princeton University Press.

- Al-Wakeel, A. Local Energy Systems in Iraq: Neighbourhood Diesel Generators and Solar Photovoltaic Generation. In Microgrids and Local Energy Systems; Jenkins, N., Ed.; IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Al-Eryani, A. The Political Economy of Energy Security in Wartime Yemen. 16, 359–370.

- Banerjee, R. Comparison of Options for Distributed Generation in India. 34, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.; Silveira, S. Alternative Pathways for Providing Access to Electricity in Developing Countries. 57, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. Aging US Power Grid Blacks Out More Than Any Other Developed Nation.

- Chu, A.; Smyth, J.; Harris, L. ‘BYOP’: Americans Bring Their Own Power with Outages on the Rise.

- Verdeil; Jaglin, S. Electrical Hybridizations in Cities of the South: From Heterogeneity to New Conceptualizations of Energy Transition. 30, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chaplain, A. ; Verdeil. Governing Hybridized Electricity Systems: The Case of Decentralized Electricity in Lebanon. pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Akrich, M. The De-Scription of Technical Objects. In Shaping Technology Building Society; Bijker, W.E.; Law, J., Eds.; MIT Press; Vol. pp, pp. 205–224.

- Callon, M. Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. 32, 196–233. [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. On Actor-Network Theory : A Few Clarifications. 47, 369–381, [22351629]. 223.

- Jasanoff, S. Ordering Knowledge, Ordering Society. In States of Knowledge. The Co-Production of Science and Social Order; Jasanoff, S., Ed.; Routledge.

- Meiton, F. Electrical Palestine: Capital and Technology from Empire to Nation; University of California Press.

- Pritchard, S.B. Confluence: The Nature of Technology and the Remaking of the Rhône; Harvard University Press.

- Venturini, T.; Munk, A. Controversy Mapping: A Field Guide, first published ed.; Cambridge : Polity.

- Malm, A. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam-Power and the Roots of Global Warming; Verso.

- Niblett, M. Energy Regimes. In Fueling Culture: 101 Words for Energy and Environment; Szeman, I., Ed.; Fordham University Press; pp. 136–139. [CrossRef]

- Larkin, B. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. 42, 327–343.

- Nucho, J.R. Post-Grid Imaginaries: Electricity, Generators, and the Future of Energy. p. 9584764. 4764. [CrossRef]

- Winner, L. Do Artifacts Have Politics? 109, 121–136.

- Edgerton, D. The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900; Oxford University Press; [E2fiBwAAQBAJ].

- Ogunleye, E.K. Political Economy of Nigerian Power Sector Reform. 391.

- Arowolo, W.; Perez, Y. Market Reform in the Nigeria Power Sector: A Review of the Issues and Potential Solutions. 144, 111580. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.D.; Usman, Z. Taking Stock of the Political Economy of Power Sector Reforms in Developing Countries: A Literature Review.

- Gabor, D. The Wall Street Consensus. 52, 429–459.

- Christophers, B. Fossilised Capital: Price and Profit in the Energy Transition. 27, 146–159. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.A., Ed. Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid; Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ireland, R.D.; Ketchen, D.J. Toward a Research Agenda on the Informal Economy. 26, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, E.; Igudia, E. The Case for Mixed Methods Research: Embracing Qualitative Research to Understand the (Informal) Economy. 28, 1947–1970. [CrossRef]

- Awofeso, N. Generator Diesel Exhaust: A Major Hazard to Health and the Environment in Nigeria. 183, 1437–1437. [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, E.; Makaza, N. Health Effects of Diesel Engine Exhaust Emissions Exposure (DEEE) Can Mimic Allergic Asthma and Rhinitis. 15, 31. [CrossRef]

- Tooze, A. Trouble Transitioning. 47.

- Fressoz, J.B. Less Not More. 47.

- Paterson, M.; Wilshire, S.; Tobin, P. The Rise of Anti-Net Zero Populism in the UK: Comparing Rhetorical Strategies for Climate Policy Dismantling. 26, 332–350. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).