Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and In Situ CH4 Measurement

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Metagenomic Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Methane Flux and Environmental Factors

3.2. Effects of Wetland Degradation on Microbial Community

3.3. Differences of CH4 Metabolism Pathways Under Different Degradation

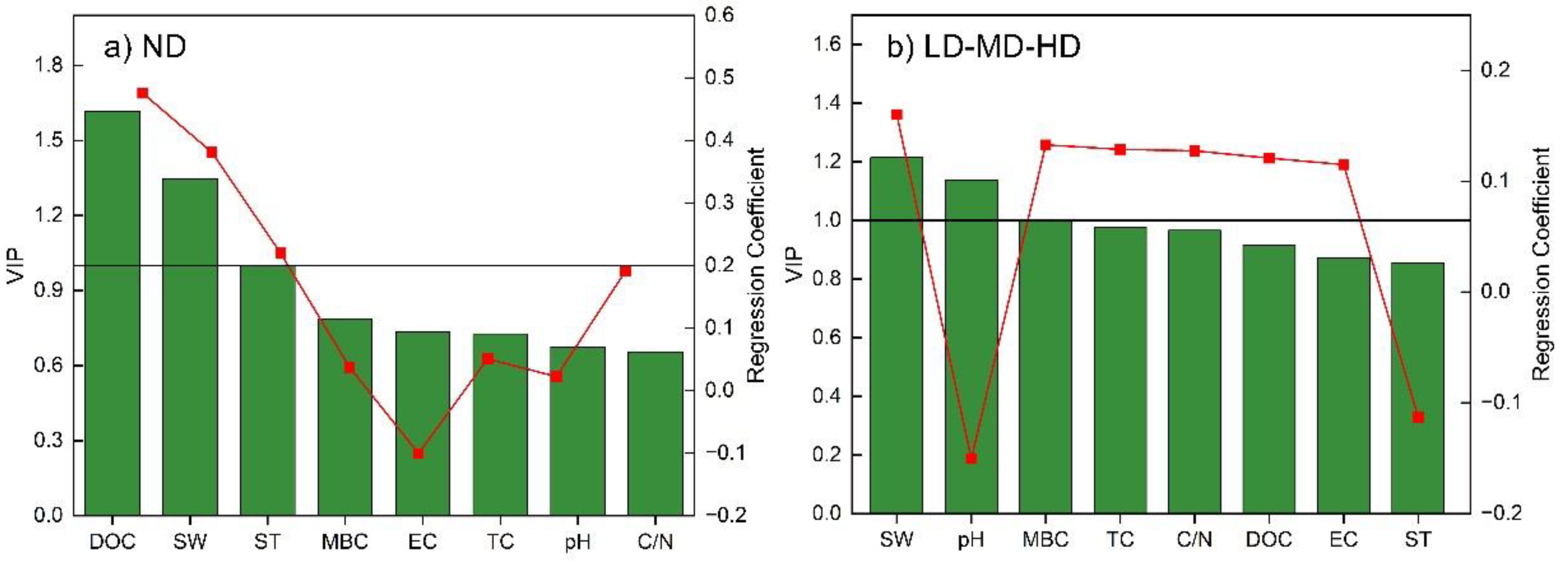

3.4. Factors Determining CH4 Emission Under Different Degradation

| Treatment | R2 | Q2 | Component | % of explained variability in Y |

Cumulative explained variability in Y (%) |

RMSECV | Q2 cum | |

| ND | 0.74 | 0.87 | 1 | 73.86 | 73.86 | 1.095 | 0.446 | |

| 2 | 22.24 | 96.10 | 0.839 | 0.871 | ||||

| LD-MD-HD | 0.78 | 0.73 | 1 | 78.06 | 78.06 | 1.029 | 0.729 | |

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Wetland Degradation on Magnitude of Methane Emissions

4.2. Effects of Wetland Degradation on Environmental Factors

4.3. Effects of Wetland Degradation on Microbial Communities Associated with Methane Production and Oxidation

4.4. Effects of Wetland Degradation on Methane Metabolism Pathways

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Wang Z, Zhao H, Zhao C. Temporal and spatial evolution characteristics of land use and landscape pattern in key wetland areas of the West Liao River Basin, Northeast China [J]. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Landscape Management 2022, 30, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone S L, Starr G, Staudhammer C L, et al. Effects of simulated drought on the carbon balance of Everglades short-hydroperiod marsh [J]. Global Change Biology 2013, 19, 2511–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedler J B, Kercher S. Wetland resources: status, trends, ecosystem services, and restorability [J]. Annu Rev Environ Resour 2005, 30, 39–74. [CrossRef]

- Khaledian Y, Kiani F, Ebrahimi S, et al. Assessment and monitoring of soil degradation during land use change using multivariate analysis [J]. Land Degradation & Development 2017, 28, 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hergoualc’h K, Hendry D T, Murdiyarso D, et al. Total and heterotrophic soil respiration in a swamp forest and oil palm plantations on peat in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia [J]. Biogeochemistry 2017, 135, 203–220. [CrossRef]

- van Lent J, Hergoualc’h K, Verchot L, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions along a peat swamp forest degradation gradient in the Peruvian Amazon: soil moisture and palm roots effects [J]. Mitigation Adapt Strategies Global Change 2019, 24, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise T, Dunn A L, Wofsy S C, et al. High sensitivity of peat decomposition to climate change through water-table feedback [J]. Nature Geoscience 2008, 1, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpert K E, Carnell P E, Trevathan-Tackett S M, et al. Reducing Emissions From Degraded Floodplain Wetlands [J]. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2020, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Günther A, Barthelmes A, Huth V, et al. Prompt rewetting of drained peatlands reduces climate warming despite methane emissions [J]. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou J, Ziegler A D, Chen D, et al. Rewetting global wetlands effectively reduces major greenhouse gas emissions [J]. Nature Geoscience 2022, 15, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Zhu X, Zuo Y, et al. Microbial mechanisms for methane source-to-sink transition after wetland conversion to cropland [J]. Geoderma 2023, 429. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zimmermann N E, Stenke A, et al. Emerging role of wetland methane emissions in driving 21st century climate change [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 9647–9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ballesta R, García-Navarro F J, Bravo Martín-Consuegra S, et al. The Impact of the Storage of Nutrients and Other Trace Elements on the Degradation of a Wetland [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research 2018, 12, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergoualc’h K, Dezzeo N, Verchot L V, et al. Spatial and temporal variability of soil N2O and CH4 fluxes along a degradation gradient in a palm swamp peat forest in the Peruvian Amazon [J]. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 7198–7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura M, Murase J, Lu Y. Carbon cycling in rice field ecosystems in the context of input, decomposition and translocation of organic materials and the fates of their end products (CO2 and CH4) [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2004, 36, 1399–1416. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Wang D, Ding Y, et al. Ebullition Controls on CH4 Emissions in an Urban, Eutrophic River: A Potential Time-Scale Bias in Determining the Aquatic CH4 Flux [J]. Environmental Science & Technology 2021, 55, 7287–7298.

- Yang P, Lai D Y, Yang H, et al. Large increase in CH4 emission following conversion of coastal marsh to aquaculture ponds caused by changing gas transport pathways [J]. Water Res 2022, 222, 118882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Zhang C-j, Liu P-f, et al. Non-syntrophic methanogenic hydrocarbon degradation by an archaeal species [J]. Nature 2022, 601, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun J, Crombie A T, Ul Haque M F, et al. Revealing the community and metabolic potential of active methanotrophs by targeted metagenomics in the Zoige wetland of the Tibetan Plateau [J]. Environmental Microbiology 2021, 23, 6520–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Yao Z, Ma L, et al. Annual methane emissions from degraded alpine wetlands in the eastern Tibetan Plateau [J]. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 657, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Kang X, Kang E, et al. Soil water content, carbon, and nitrogen determine the abundances of methanogens, methanotrophs, and methane emission in the Zoige alpine wetland [J]. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2021, 22, 470–481.

- Dou X, Zhou W, Zhang Q, et al. Greenhouse gas (CO2, CH4, N2O) emissions from soils following afforestation in central China [J]. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 126, 98–106. [CrossRef]

- McCalley C K, Woodcroft B J, Hodgkins S B, et al. Methane dynamics regulated by microbial community response to permafrost thaw [J]. Nature 2014, 514, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buan N, R. Methanogens: pushing the boundaries of biology [J]. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 2018, 2, 629–646. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M, W. Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase Genes: Unique Functional Markers for Methanogenic and Anaerobic Methane-Oxidizing Archaea [M]. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press. 2005; 428–442. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoping T, Guilin H. Study on classification system for wetland types in China [J]. Forest Research 2003, 16, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Xu X, Tian H, et al. Ecosystem–atmosphere exchange of CH4 and N2O and ecosystem respiration in wetlands in the Sanjiang Plain, Northeastern China [J]. Global Change Biol 2009, 15, 692–705. [CrossRef]

- Padhy S R, Bhattacharyya P, Dash P K, et al. Elucidation of dominant energy metabolic pathways of methane, sulphur and nitrogen in respect to mangrove-degradation for climate change mitigation [J]. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 303, 114151. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar H, Lupascu M, Sukri R S, et al. Significant sedge-mediated methane emissions from degraded tropical peatlands [J]. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16, 014002. [Google Scholar]

- Abulaizi M, Chen M, Yang Z, et al. Response of soil bacterial community to alpine wetland degradation in arid Central Asia [J]. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 13, 990597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan Z, Yang S, Chen L, et al. Responses of soil fungal community composition and function to wetland degradation in the Songnen Plain, northeastern China [J]. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15.

- Vargas A I, Schaffer B, Sternberg L d S L. Plant water uptake from soil through a vapor pathway [J]. Physiologia Plantarum 2020, 170, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulaizi M, Chen M, Yang Z, et al. Response of soil bacterial community to alpine wetland degradation in arid Central Asia [J]. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 990597. [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Gao J, Wang N, et al. Differences in soil microbial response to anthropogenic disturbances in Sanjiang and Momoge Wetlands, China [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2019, 95, fiz110.

- Huo L, Chen Z, Zou Y, et al. Effect of Zoige alpine wetland degradation on the density and fractions of soil organic carbon [J]. Ecological Engineering 2013, 51, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li M, Hao Y, Yan Z, et al. Long-term degradation from marshes into meadows shifts microbial functional diversity of soil phosphorus cycling in an alpine wetland of the Tibetan Plateau [J]. Land Degradation & Development 2022, 33, 628–637. [Google Scholar]

- Wan D, Yu P, Kong L, et al. Effects of inland salt marsh wetland degradation on plant community characteristics and soil properties [J]. Ecological Indicators 2024, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Qi Q, Tong S, et al. Soil Degradation Effects on Plant Diversity and Nutrient in Tussock Meadow Wetlands [J]. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2019, 19, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy S R, Bhattacharyya P, Nayak S K, et al. A unique bacterial and archaeal diversity make mangrove a green production system compared to rice in wetland ecology: A metagenomic approach [J]. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 781, 146713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Yu L, Zhang Z, et al. Molecular mechanisms of water table lowering and nitrogen deposition in affecting greenhouse gas emissions from a Tibetan alpine wetland [J]. Global change biology 2017, 23, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma W, Alhassan A-R M, Wang Y, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions as influenced by wetland vegetation degradation along a moisture gradient on the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of North-West China [J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2018, 112, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra F A, Prior S A, Runion G B, et al. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide and increased temperature on methane and nitrous oxide fluxes: evidence from field experiments [J]. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2012, 10, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller S, Goenrich M, Boecher R, et al. The key nickel enzyme of methanogenesis catalyses the anaerobic oxidation of methane [J]. Nature 2010, 465, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermler U, Grabarse W, Shima S, et al. Crystal Structure of Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase: The Key Enzyme of Biological Methane Formation [J]. Science 1997, 278, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruiz P, Gómez-Borraz T L, Revah S, et al. Methanotroph-microalgae co-culture for greenhouse gas mitigation: Effect of initial biomass ratio and methane concentration [J]. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho A, Kerckhof F-M, Luke C, et al. Conceptualizing functional traits and ecological characteristics of methane-oxidizing bacteria as life strategies [J]. Environmental Microbiology Reports 2013, 5, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou Y, Wei K, Li C, et al. Deterministic processes dominate soil methanotrophic community assembly in grassland soils [J]. Geoderma 2020, 359, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Cai Y, Jia Z. The pH-based ecological coherence of active canonical methanotrophs in paddy soils [J]. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng S, Deng S, Ma C, et al. Type I methanotrophs dominated methane oxidation and assimilation in rice paddy fields by the consequence of niche differentiation [J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2023, 60, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fest B, Hinko-Najera N, von Fischer J C, et al. Soil methane uptake increases under continuous throughfall reduction in a temperate evergreen, broadleaved eucalypt forest [J]. Ecosystems 2017, 20, 368–379. [CrossRef]

- Brumme R, Borken W. Site variation in methane oxidation as affected by atmospheric deposition and type of temperate forest ecosystem [J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 1999, 13, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith K A, Ball T, Conen F, et al. Exchange of greenhouse gases between soil and atmosphere: interactions of soil physical factors and biological processes [J]. European journal of soil science 2018, 69, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Wang J, Hu B. How methanotrophs respond to pH: a review of ecophysiology [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 13, 1034164. [Google Scholar]

- Tamas I, Smirnova A V, He Z, et al. The (d) evolution of methanotrophy in the Beijerinckiaceae—a comparative genomics analysis [J]. The ISME journal 2014, 8, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyuzhnaya M G, Yang S, Rozova O N, et al. Highly efficient methane biocatalysis revealed in a methanotrophic bacterium [J]. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier P L E, Meima-Franke M, Hordijk C A, et al. Microbial minorities modulate methane consumption through niche partitioning [J]. The ISME Journal 2013, 7, 2214–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria [J]. Microbiological reviews 1996, 60, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakemian A S, Rosenzweig A C. The biochemistry of methane oxidation [J]. Annu Rev Biochem 2007, 76, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma W, Alhassan A-R M, Wang Y, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions as influenced by wetland vegetation degradation along a moisture gradient on the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of North-West China [J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2018, 112, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Naafs B D A, Huang X, et al. Variations in wetland hydrology drive rapid changes in the microbial community, carbon metabolic activity, and greenhouse gas fluxes [J]. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2022, 317, 269–285. [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Chen J, Zhou F, et al. Relative increases in CH4 and CO2 emissions from wetlands under global warming dependent on soil carbon substrates [J]. Nature Geoscience 2024, 17, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelbener A, Ström L, Edwards P J, et al. Plant species from mesotrophic wetlands cause relatively high methane emissions from peat soil [J]. Plant and Soil 2010, 326, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneyew B G, Assefa W W. Anthropogenic effect on wetland biodiversity in Lake Tana Region: A case of Infranz Wetland, Northwestern Ethiopia [J]. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2021, 12.

- Craine J M, Gelderman T M. Soil moisture controls on temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition for a mesic grassland [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2011, 43, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams R T, Crawford R L. Methane production in Minnesota peatlands [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1984, 47, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn M A, Matthies C, Kusel K, et al. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis by moderately acid-tolerant methanogens of a methane-emitting acidic peat [J]. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsyurbenko O R, Friedrich M W, Simankova M V, et al. Shift from Acetoclastic to H2-Dependent Methanogenesis in a West Siberian Peat Bog at Low pH Values and Isolation of an Acidophilic Methanobacterium Strain [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007, 73, 2344–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Sun Y, Li L, et al. Acclimation of acid-tolerant methanogenic propionate-utilizing culture and microbial community dissecting [J]. Bioresour Technol 2018, 250, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Ban Q, Li J, et al. Response of Syntrophic Propionate Degradation to pH Decrease and Microbial Community Shifts in an UASB Reactor [J]. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 26, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song H, Peng C, Zhu Q, et al. Quantification and uncertainty of global upland soil methane sinks: Processes, controls, model limitations, and improvements [J]. Earth-Science Reviews 2024, 252.

- Le Mer J, Roger P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review [J]. European Journal of Soil Biology 2001, 37, 25–50. [CrossRef]

- Dinsmore K J, Skiba U M, Billett M F, et al. Effect of water table on greenhouse gas emissions from peatland mesocosms [J]. Plant and Soil 2009, 318, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang G, Chen H, Wu N, et al. Effects of soil warming, rainfall reduction and water table level on CH4 emissions from the Zoige peatland in China [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2014, 78, 83–89. [CrossRef]

- Bhullar G S, Edwards P J, Olde Venterink H. Variation in the plant-mediated methane transport and its importance for methane emission from intact wetland peat mesocosms [J]. Journal of Plant Ecology 2013, 6, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Methanogens | ND | LD | MD | HD | p value |

| hydrogenotrophic methanogens | Methanocellales | 324.54 ± 80.42 a | 1.49 ± 1.01 b | 1.44 ± 0.62 b | 0.88 ± 0.64 b | <0.01 |

| Methanobacteriales | 396.27 ± 73.90 a | 1.64 ± 1.37 ab | 0.50 ± 0.33 b | 0.69 ± 1.37 b | <0.01 | |

| Methanococcales | 29.94 ± 7.99 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | < 0.001 | |

| Methanomicrobiales | 183.49 ± 36.05 a | 0.79 ± 1.29 ab | 0.099 ± 0.15 b | 0.06 ± 0.10 b | <0.01 | |

| Methanopyrales | 3.94 ± 0.92 a | 0.18 ± 0.23 ab | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | < 0.001 | |

| methylotrophic methanogens | Methanomassiliicoccales | 72.94 ± 18.45 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.03 ± 0.05 b | 0.14 ± 0.22 b | <0.01 |

| Methanonatronarchaeales | 1.32 ± 0.53 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | < 0.001 | |

| Acetate- degrading methanogens | Methanothrix | 163.48 ± 50.81 a | 0.16 ± 0.24 ab | 0.03 ± 0.07 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | < 0.001 |

| Methanosarcina | 22.73 ± 5.15 a | 0.32 ± 0.35 b | 0.02 ± 0.05 b | 0.19 ± 0.32 b | <0.01 | |

| facultative methanogen | Methanosarcinales | 719.18 ± 149.06 a | 0.36 ± 0.40 b | 0.19 ± 0.13 b | 0.35 ± 0.49 b | <0.01 |

| Category | Methanotrophs | ND | LD | MD | HD | p value |

| Type II methanotrophs | Beijerinckiaceae | 16.21 ± 4.06 b | 30.02 ± 2.34 ab | 38.85 ± 4.29 a | 32.17 ± 2.42 ab | < 0.001 |

| Methylocystaceae | 27.53 ± 12.95 a | 19.19 ± 5.67 a | 19.50 ± 1.71 a | 19.24 ± 3.53 a | 0.457 | |

| Type I methanotrophs | Methylococcaceae | 22.13 ± 13.11 a | 2.58 ± 0.86 ab | 2.38 ± 0.89 b | 1.74 ± 0.72 b | <0.01 |

| Verrucomicrobia | Verrucomicrobiaceae | 3.75 ± 1.01 a | 0.70 ± 0.25 b | 1.16 ± 0.20 b | 1.00 ± 0.47 b | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).