I. Information nudging in the Platform Context

In the current platform environment, numerous content label forms for information nudging are present. Through a systematic examination of platform practices, the author has determined that there exists a distinct correspondence between these prototypes and the mainstream content label modalities on the platform. Among these, warning labels designed to suppress misinformation and certification labels aimed at promoting authenticity are the two most prevalent methods in practical applications. These two types of labels respectively commence from two critical aspects: discerning the accuracy of information content and evaluating the reliability of information sources. By means of specific label formats, they effectively direct and regulate the flow of information on the platform.

Subsequently, what represents the most typical and fundamental operationalization approach for information nudging within research? When reviewing existing inquiries into the effects of information nudging, researchers often operationalize information nudging into diverse content label expressions in accordance with their research requirements. The utilization of different operationalization methods might result in contradictory and disjointed research findings concerning the governance efficacy of information nudging. These isolated and scattered studies, which lack unification under fixed criteria, could potentially undermine our fundamental comprehension of the governance impacts of information nudging and content labels, as well as impede the further advancement of this field. Consequently, it is essential to distill the operationalization methods of information nudging to systematically validate its effects and bridge the gaps in research outcomes stemming from different operationalizations.

Specifically, a common research design involves operationalizing it as an error - suppressing warning label, namely the fact - warning label, which is presented in statements like alerting users that the information has not passed fact - checking (Nekmat, 2020; Shin et al., 2023). Another common research design is to operationalize it as a truth - promoting certification label, that is, the fact - certification label, presented in statements such as notifying users that the information has passed fact - checking and has been authenticated (Oeldorf - Hirsch et al., 2023). Additionally, numerous studies have delved deeper into the influence of various element variations of these labels on the label governance effect, such as multimodal labels (Jaynes & Boles, 1990), popularity labels (Xiang et al., 2023), and so on. Chan J et al. (2022) further discovered that including some risk details in warning labels can enhance the nudging effect of the labels. Ecker et al. (2020) also verified that the more abundant the risk details are, the more pronounced the intervention effect on users' information consumption behavior becomes. These studies are all conducted based on the additional variations of the aforementioned two operationalization methods, falling into the realm of advanced research rather than the investigation of the universal effects of information nudging.

II. Error Suppression and Truth Promotion: Differences in the Context of Platform Content Governance

Due to the differences in media systems among different countries, there are also significant differences in the operational expressions and research results of warning labels and authentication labels. There are differences in information nudging in the platform contexts of different countries: Firstly, there are differences in label preferences. Some countries represented by China tend to use truth-promoting authentication labels, and directly adopt the measure of deleting false information, with fewer error-suppressing warning labels. Some countries represented by the United States, on the other hand, tend to use error-suppressing warning labels and fully retain false information on the platform. Secondly, the main bodies of fact-checking actions are different, which leads to differences in the generation process of content labels such as warning labels and authentication labels.

Under the media system of the free market, since FactCheck.org was launched in the United States in 2003, the fact-checking movement has been booming globally. North American and European countries have successively established more than 300 fact-checking agencies that specifically provide fact-checking services (Singer, 2018). These agencies are third-party profit-making organizations independent of the government and the media (Humprecht, 2019). For example, the fact-checking website Snopes established in the United States in 1994 is considered one of the earliest and most well-known fact-checking agencies on the Internet, mainly verifying and refuting various rumors and urban legends. In addition, The Fact Checker fact-checking column created by The Washington Post has gradually developed into an independent fact-checking agency, which is committed to fact-checking political speeches and campaign advertisements. Full Fact is a British fact-checking agency established in 2008, which mainly uses a combination of manual checking and automated tools to conduct fact-checking on news and statements in the fields of politics, economy, society, etc. There are also many other third-party fact-checking agencies of this kind.

Many fact-checking labels are issued with the help of third-party fact-checking agencies. For example, platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok have already outsourced the work of evaluating the authenticity of content to these third-party fact-checking agencies in some form of cooperation. The organizations that Facebook cooperates with include fact-checking agencies such as Newsguard, FactCheck.org, and PolitiFact, and WhatsApp provides fact-checking resources through the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) on WhatsApp. Of course, these third-party fact-checking agencies representing authoritative judgments are not the only issuers of fact-checking labels. Some platforms will also combine supplementary technical identification with the wisdom of user groups.

III. Certification or Warning: Issues and Hypotheses Based on Governance Logic

The discussion commences with the choice between using certification labels and warning labels. Underlying these two forms of labels are the disparities in two governance logics: truth - promotion and error - suppression. The certification label represents the Confirmation Frame, while the warning label represents the Refutation Frame (Aruguete et al., 2023). Semantic research has firmly established that, in comparison to the refutation frame, the confirmation frame exerts a more positive influence on social communication. This is because it is a common belief that telling the truth is virtuous and telling lies is immoral (Kaup et al., 2006), and at the individual level, negative sentences impose a heavier cognitive burden than positive ones (Christensen, 2020:725 - 739). Consequently, these two framing expressions have a profound impact on an individual's perception of content quality. The confirmation frame tends to enhance an individual's perception of content quality, whereas the refutation frame has a diminishing effect (Oeldorf - Hirsch et al., 2023).

Furthermore, numerous scholars have delved into the impact of these two frames on an individual's information - consumption behavior. They have discovered that although the semantic meanings expressed by the two frames are equivalent, people are more inclined to disseminate and share fact - checking presented in a supportive attitude rather than in an opposing one (Shin & Thorson, 2017; Ekstrom & Lai, 2020). This is attributable to the fact that the low - cognitive - burden confirmation frame is more likely to trigger an individual's Hot Cognition - a spontaneous and rapid process. In contrast, the refutation frame is more likely to evoke an individual's deliberate and slow Cold Cognition. Comparatively, Hot Cognition is more conducive to eliciting outward - directed sharing and dissemination behaviors (Aruguete et al., 2023). In light of this, it is postulated that warning or certification labels can nudge changes in an individual's content evaluation and also influence their information - interaction behaviors. Thus, the following research hypotheses are put forward:

H1: Compared with the absence of content labels, text certification labels will result in: (a) a higher perception of information credibility, and (b) more active information - interaction behaviors.

H2: Compared with the absence of content labels, text warning labels will lead to: (a) a lower perception of information credibility, and (b) less active information - interaction behaviors.

Subsequently, the discussion turns to whether the labels of the platform - self - built verification resources possess a nudging effect. Internet users generally have a relatively high level of awareness regarding the generation and production processes of content labels and a basic understanding of content labels as a form of content review. However, in some countries, many users are unaware of how these warning and certification labels are crafted and generated, and they have no knowledge of the entities providing these labels and verification services. As a result, users may even harbor doubts about the labels, which might potentially lead to more cognitive resistance. On the other hand, even for those users who have some understanding of the generation and production processes of content labels, they may not necessarily accept and trust this content - review method (Liu & Zhou, 2022). Users often question the professionalism and authority of the platform's content determination and frequently challenge and refute the content - adjudication results of platform auditors (Einwiller & Kim, 2020). Therefore, it remains uncertain whether these content labels generated and produced by the platform can gain authoritative recognition from users and whether they can achieve the expected nudging effect. Hence, the following research question is raised:

RQ1: When users are aware that the content labels are produced through the platform - self - built fact - checking resources, will they still exhibit the same nudging effect?

In addition, an exploration of the information nudging effect from a cognitive perspective is also of interest. Previous studies on the nudging effect have been plagued by a lack of in - depth cognitive - measurement tools and have mainly relied on self - reporting methods such as questionnaires or behavioral experiments. In recent years, a multitude of researchers (including many communication scholars) have started to employ cognitive - neuroscience measurement tools such as electroencephalography (EEG), eye - tracking, and infrared technology. These tools measure an individual's physiological indicators to assess the user's information - processing level and explain communication - effect issues. EEG measurement tools are the most suitable and crucial instruments for exploring the user's information - cognition process (Clark et al., 2018). They can meticulously and objectively record and reflect an individual's cognitive engagement and mental workload, thereby revealing the individual's implicit and real - time cognitive performance. Currently, research on the brain activities in information processing triggered by information nudging is still in its infancy. Based on this, the following research question is proposed:

RQ2: How will content labels influence the brain - cognitive activities of users during information processing?

IV. Experimental Methods

This study adopts a between - subjects experimental design with a 2 (Nudge type: text warning label vs. text certification label) × 2 (awareness of the nudge subject: aware vs. unaware) factorial arrangement, and an additional control condition group with no nudge element of information displayed. All participants are randomly assigned to any one of the experimental conditions.

The manipulation of the nudge type is as follows: in the warning label condition, warning labels are marked on the reading materials, and in the certification label condition, certification labels are marked on the reading materials. The manipulation of the awareness of the nudge subject is as follows: in the aware condition, a lead - in statement is added before the experiment to inform the participants of the generation process of the content labels, while in the unaware condition, no such lead - in statement is added.

4.1. Experimental Subjects

G*Power 3.1 was employed to calculate the effect size, statistical power, and the number of subjects to be recruited. The results indicated that a minimum of 90 subjects was required to achieve a moderate effect size (f = 0.4) and an appropriate statistical power (1 - β = 0.8). In this experiment, a total of 100 undergraduate and postgraduate students were recruited, representing diverse disciplinary and cultural backgrounds.

To avoid the interference of prior familiarity and ensure that all subjects engaged attentively in news reading, a pre - experimental screening regarding topic familiarity was conducted. This screening consisted of two questions: Have you heard of this topic? and Have you seen any written or video materials related to this topic? Both questions were measured using a 7 - point Likert scale. Subjects whose scores on each question exceeded ±3 standard deviations were excluded. Additionally, a post - experimental screening for reading attention was carried out. Two reading - detail verification questions were adapted from the content details of the reading text. Subjects who answered these questions incorrectly were excluded.

Consequently, 2 subjects were excluded due to topic familiarity, 3 subjects were excluded based on the reading - attention check, and another 3 subjects were excluded because they failed the manipulation check. The sample sizes for each experimental condition are presented in

Table 1.

The final sample consisted of 92 subjects (43 males and 49 females), with a mean age of 22.72 ± 2.48 years. All subjects had normal or corrected - to - normal vision, were right - handed, and had no current or past history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. They were not taking any medications known to affect the central nervous system.

Prior to the experiment, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) were used to assess the subjects' recent emotional states. The results were as follows: BAI score was 26.13 ± 4.67, BDI score was 6.91 ± 6.76, negative affect score was 15.28 ± 5.77, and positive affect score was 28.59 ± 8.07. None of the subjects exhibited significant clinical anxiety or depressive symptoms. All subjects provided informed consent and received corresponding monetary compensation after the experiment.

4.2. Experimental Materials

4.2.1. Reading Materials for the Experimental Reading Task

The reading materials for the experimental reading task were selected as follows. Initially, five news texts were chosen. To eliminate potential confounding factors associated with the materials, eleven master's students with similar professional backgrounds were recruited in advance to rate these five texts. The ratings covered two aspects: emotional bias and content controversiality, both of which were measured using a 7 - point Likert scale. Subsequently, among the 60 texts (resulting from the combination of the five texts and the ratings), those with scores of emotional bias or content controversiality exceeding ±3 standard deviations were removed. From the remaining texts, the one with scores of both aspects closest to the mid - value of 3.5 was selected as the final reading material for the experiment. The ultimately chosen news text was a descriptive social news report with a title of approximately 10 words and a body text of around 4000 words, and its theme was Heavy Rainfalls in Many Places, and Meteorological Experts Warn of Caution.

4.2.2. Experimental Stimulus Manipulation

Regarding the warning label and the certification label, the design was based on the fact - checking label cases on the platforms. The labels were presented in the form of a gray - background and white - text prompt bar between the title and the body text of the reading material. The warning label read This content has not been verified and checked, while the certification label read This content has been verified and checked. The manipulation of user awareness was mainly achieved through an introduction. In the aware condition, users would see a description of the content label generation process in the introduction when entering the experiment: The platform uses content labels for fact - checking to prompt users. These content labels are provided by an in - house manual review team of the platform. The manual review team of the platform will attach corresponding labels to the relevant content after verification and inspection. In the unaware condition, users would not see this description in the introduction.

4.3. Experimental Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the experimental conditions. The reading materials containing experimental manipulations were presented to the participants via a computer. At the commencement of the formal experiment, the participants entered a bright, quiet, and enclosed experimental room, which was isolated from external electromagnetic signals and noise. The participants were seated on a chair 50 centimeters away from a desktop computer and informed that they were required to complete a news - reading and judgment task on the desktop computer. Subsequently, they wore an electroencephalogram (EEG) cap. Once the participants started reading the materials, the EEG signals during their news - reading process were recorded, and the recording ceased upon the completion of reading. After that, the participants were asked to answer a series of questionnaire items related to manipulation checks and the measurement of dependent variables, and then the experiment ended.

4.4. Data Measurement and Analysis

Self - report data were collected using scale questionnaires. The measurement mainly involved two dependent variables:

(1) Perceived information credibility. Based on the research of Oeldorf - Hirsch et al. (2023), it was measured by three questions: How accurate do you think this information is? / How true do you think this information is? / How credible do you think this information is? A 7 - point Likert scale was used for measurement (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), and finally, the average score of the three questions was calculated as the perceived information credibility score.

(2) Willingness to interact with information. According to the research of Oh et al. (2015), it was measured by three questions: Do you want to like this information? / Do you want to comment on this information? / Do you want to forward this information? A 7 - point Likert scale was used for measurement (1 = strongly do not want, 7 = strongly want), and the average score of the three questions was calculated as the willingness - to - interact - with - information score. The questionnaire data were collected through the Wenjuanxing platform and statistically analyzed using SPSS 26.0.

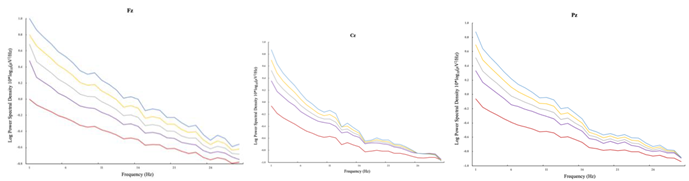

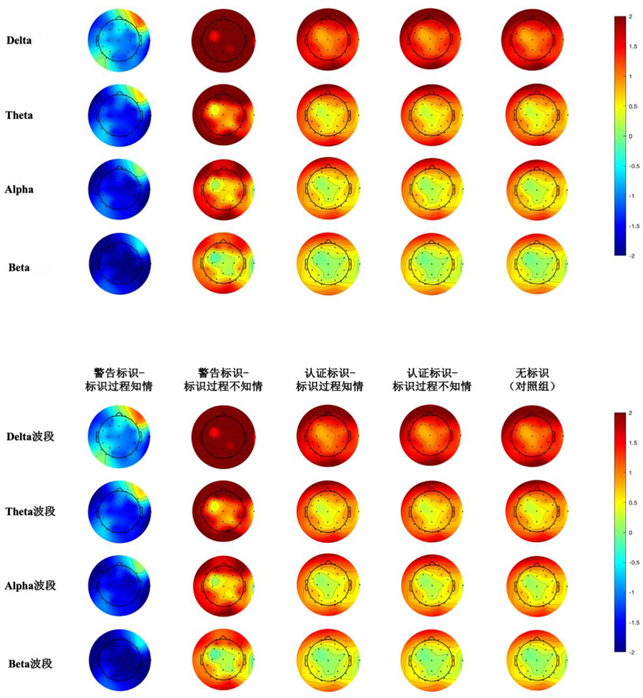

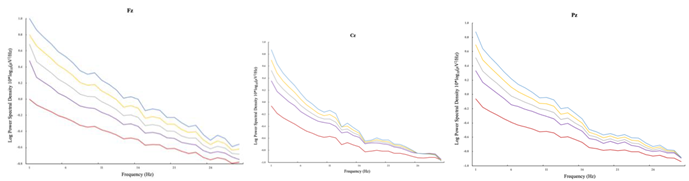

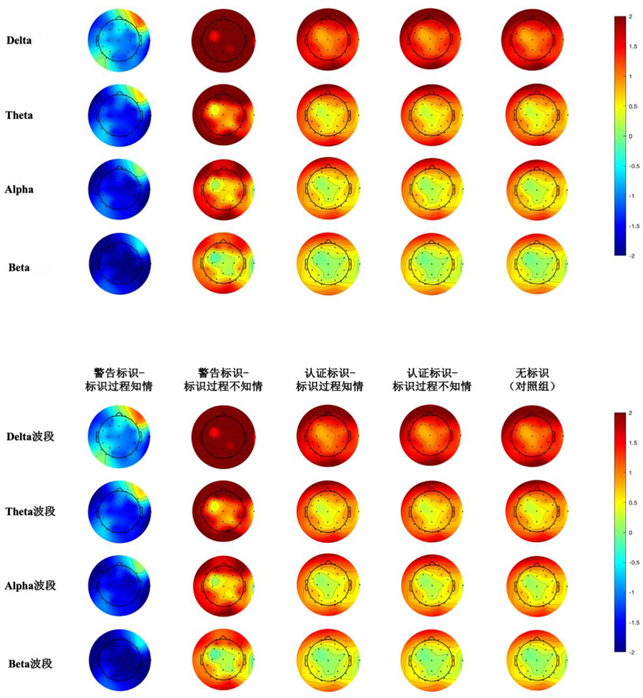

The electroencephalogram (EEG) data were recorded and collected using a 32 - channel wireless dry - electrode electroencephalograph of Cognionics Quick - 30 (CGX, San Diego, CA, United States). The channel positions were arranged according to the 10 - 20 system. The sampling rate of the EEG data was 1000 Hz, with direct - current recording. The ground was set at the forehead, and the recording bandwidth was 0 - 100 Hz. During the recording, the left mastoid was used as the reference electrode, and the data were converted to the average reference value of the bilateral mastoids for offline analysis. The EEG data were analyzed using EEGLAB 2023. First, the EEG signals were subjected to a 1 - 30 Hz band - pass filter, and then the EEG signals with large drifts were manually removed. Independent component analysis (ICA) was used to remove artifacts such as blinks, eye movements, and head movements. After obtaining clean data, the data from 9 electrode points, namely F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4, were selected for offline analysis. The power spectral density (PSD) values of the Delta (1 - 4 Hz), Theta (4 - 8Hz), Alpha (8 - 13 Hz), and Beta (13 - 30 Hz) bands at the 9 electrode points were extracted using the Fast Fourier Transform (with a Hanning window function, 1s width, and a 50% overlap ratio) function.

V. Experimental Results

5.1. Manipulation Checks

For the manipulation check of content labels, a question Did you see the content label? was set in the post - experimental questionnaire. Two participants were excluded as they did not notice the appearance and disappearance of the content label, while the rest passed the manipulation check.

Regarding the manipulation check of the awareness of the content - label subject, a question Did you see the introduction to the generation process of the content label? was also set in the post - experimental questionnaire. One participant was excluded for not noticing it, and the remaining participants passed the manipulation check.

5.2. Information Credibility Perception

Table 2 presents the statistical results of the information credibility perception scores of the participants under each experimental condition.

First, a one - way analysis of variance (One - Way ANOVA) was conducted to examine the differences in participants' information credibility perception under different types of information nudge labels. The results showed that the nudge type had a significant impact on participants' information credibility perception, F(2,89) = 24.606, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.356. The Bonferroni post - hoc comparison results indicated that the participants' information credibility perception in the warning - label condition was significantly lower than that in the no - label condition, and the participants' information credibility perception in the certification - label condition was significantly higher than that in the no - label condition. Thus, H1a and H2a were supported.

Subsequently, a univariate analysis of variance (Univariate) was performed to explore the impact of the participants' awareness of the nudge subject on their information credibility perception. The results showed that the main effect of the awareness of the nudge subject was not significant, F(4,87) = 0.074, p = 0.787, η²p = 0.001; the interaction effect between the awareness of the label and the label type was also not significant, F(4,87) = 0.017, p = 0.897, η²p = 0.001; meanwhile, the main effect of the label type remained significant, F(4,87) = 48.156, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.356. The Bonferroni post - hoc comparison results still showed that the participants' information credibility perception in the warning - label condition was significantly lower than that in the no - label condition, and the participants' information credibility perception in the certification - label condition was significantly higher than that in the no - label condition. Evidently, the fact that users know that the content labels are issued by the platform's self - built verification resources does not affect the nudge effect of the content labels themselves, and RQ1 was partially answered.

5.3. Information Interaction Willingness

Table 3 presents the statistical results of the information interaction willingness scores of the participants under each experimental condition.

First, a one - way analysis of variance (One - Way ANOVA) was carried out to test the differences in participants' information interaction willingness under different types of information nudge labels. The results demonstrated that the nudge type had a significant impact on information interaction willingness, F(2,89) = 14.619, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.247. The Bonferroni post - hoc comparison results indicated that the participants' information interaction willingness in the warning - label condition was significantly lower than that in the no - label condition, while the difference in the participants' information interaction willingness between the certification - label condition and the no - label condition was not significant. Further examination by separating the three measurement dimensions of information interaction willingness revealed that the presence or absence of labels had a significant impact on the willingness to like and forward information, F(2,89) = 17.077, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.277, F(2,89) = 27.050, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.378. The Bonferroni post - hoc comparison results showed that the participants' willingness to forward information in the warning - label condition was significantly lower than that in the no - label condition, and the participants' willingness to like information in the certification - label condition was significantly higher than that in the no - label condition. Evidently, the impact of label types on users' information interaction willingness was mainly manifested in the dimensions of liking and forwarding, rather than the commenting dimension. The warning label had a significant nudge effect of suppressing forwarding, and the certification label had a significant nudge effect of increasing liking and forwarding. Therefore, H1b and H2b were partially supported.

Subsequently, a univariate analysis of variance (Univariate) was performed to explore the impact of the awareness of the information nudge subject on the participants' information interaction willingness. The results showed that the main effect of the awareness of the nudge subject was not significant, F(4,87) = 0.135, p = 0.714, η²p = 0.002; the interaction effect between the awareness of the label and the label type was also not significant, F(4,87) = 0.135, p = 0.714, η²p = 0.002; meanwhile, the main effect of the label type remained significant, F(4,87) = 52.744, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.377. The Bonferroni post - hoc comparison results showed that the participants' information interaction willingness in the warning - label condition was significantly lower than that in the no - label condition, and the participants' information interaction willingness in the certification - label condition was significantly higher than that in the no - label condition. This difference was still mainly reflected in the dimensions of information liking and forwarding. Evidently, the fact that users know that the content labels are issued by the platform's self - built verification resources does not affect the nudge effect of the content labels themselves, and RQ1 was partially answered.

Table 4.

The power spectral density of brain electrical activity under various experimental conditions (μV2/Hz) (M ± SD).

Table 4.

The power spectral density of brain electrical activity under various experimental conditions (μV2/Hz) (M ± SD).

| |

|

No identification is allowed in the main text |

Authentication identification in the main text |

No identification (control group) |

| |

|

Be informed during the identification process |

Be uninformed during the identification process |

Be informed during the identification process |

Be uninformed during the identification process |

Delta Band

(1-4Hz)

|

Frontal |

7.27 ± 3.32 |

5.27 ± 3.73 |

6.07 ± 3.40 |

6.03 ± 3.65 |

5.95 ± 3.99 |

| Central |

6.05 ± 3.97 |

7.18 ± 3.33 |

5.46 ± 2.97 |

6.54 ± 3.58 |

7.70 ± 3.07 |

| Parietal |

6.83 ± 3.60 |

5.65 ± 3.64 |

4.93 ± 3.38 |

4.77 ± 3.79 |

5.85 ± 3.96 |

Theta Band

(4-8Hz)

|

Frontal |

2.49 ± 0.51 |

2.41 ± 0.49 |

2.49 ± 0.50 |

2.47 ± 0.59 |

2.63 ± 0.69 |

| Central |

2.95 ± 2.10 |

2.52 ± 1.48 |

2.29 ± 0.90 |

2.16 ± 0.72 |

2.46 ± 1.64 |

| Parietal |

2.26 ± 1.31 |

2.15 ± 1.46 |

2.19 ± 1.21 |

1.92 ± 0.97 |

2.23 ± 1.63 |

Alpha Band

(8-13Hz)

|

Frontal |

5.01 ± 3.28 |

3.52 ± 3.14 |

2.93 ± 2.40 |

3.10 ± 2.60 |

3.20 ±2.44 |

| Central |

4.33 ± 2.66 |

4.61 ± 3.41 |

3.63 ± 2.30 |

3.53 ± 2.84 |

3.09 ±2.32 |

| Parietal |

4.85 ± 3.00 |

4.41 ± 3.26 |

3.62 ± 2.19 |

3.36 ± 2.43 |

4.03 ± 2.85 |

Beta Band

(13-30Hz)

|

Frontal |

1.44 ± 4.34 |

1.36 ± 4.59 |

2.02 ± 3.44 |

1.65 ± 4.56 |

1.66 ± 4.36 |

| Central |

0.87 ± 5.54 |

0.08 ± 4.36 |

0.31 ± 4.30 |

0.43 ± 5.74 |

0.76 ± 4.25 |

| Parietal |

0.81 ± 3.07 |

0.10 ± 4.59 |

0.20 ± 4.40 |

0.24 ± 4.67 |

1.31 ± 4.37 |

VI. Results Discussion

Set against the backdrop of information nudging in the platform context, this chapter attempts to explore the impact of information nudging on users' content perception and interaction willingness. By setting two nudging scenarios (fact - warning label vs. fact - certification label) and two nudging awareness conditions (aware of the nudging subject vs. unaware of the nudging subject), the participants' information credibility perception, information interaction willingness, and micro - level electroencephalogram (EEG) activity index changes were examined. The behavioral results show that, compared with the non - nudging control condition, regardless of whether users are aware of the nudging subject, the fact - warning label can significantly reduce users' information credibility perception and information interaction willingness, and the fact - certification label can significantly enhance users' information credibility perception and their willingness to like and forward information. Thus, H1a and H2a are supported, and H1b and H2b are partially supported. The EEG results show that in the Alpha band, the main effect of the nudging type is significant, and the fact - warning label can significantly increase the Alpha - band activity in users' brains; moreover, no significant effects of the experimental manipulation conditions on the activities of other brain regions were found. The following elaborates on these main results.

6.1. The nudging Type Significantly Affects Information Credibility Perception

The experiment reveals that content labels, as a means of fact - check nudging, can produce significant nudging effects. That is, the valence of content labels (warning or certification) further influences individuals' judgment of information credibility.

This finding is consistent with previous research results on information consumption and the heuristic - cue effect (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972). As a heuristic cue when users encounter information, content labels can potentially clarify the implicit information in news and activate users' existing cognitive biases to complete subsequent cognitive processing activities (Otis, 2022). Fact - checking labels, as a means of disclosing information quality, can affect users' credibility assessment of labeled information by triggering users' previous information - consumption experiences (Nekmat, 2020; Liu et al., 2023). However, the effect in this experiment is larger than that in previous fact - checking - label studies, and the nudging effect is more obvious, showing some inconsistency. Previous studies have shown that the impact of information nudging on users' cognition is not significant, and when evaluating information quality, the influence of the content itself is greater than that of content labels (Aruguete et al., 2023). Moreover, some research results even show that the impact of content labels on information evaluation is minimal (Oeldorf - Hirsch et al., 2023). These studies emphasize that users' directional beliefs (such as prior preferences, prior motives, political inclinations, party choices, media biases, etc.) are the decisive factors in determining users' information perception. Minor interface cues such as content labels can only have a significant effect when they conform to users' directional beliefs or are consistent with them (Weeks & De Zúñiga, 2019). The reason for the inconsistent conclusions may be that, considering the actual application context of current fact - checking labels on Chinese platforms, the reading text selected in this experiment is a popular science and social article related to scientific knowledge. In other studies, scholars considered the label - application context of the platform, and the selected reading texts were all highly political news such as political news and election news. Relatively speaking, the intensity of directional beliefs activated by users when consuming articles on the two themes is different. Directional beliefs and motives are more important in the consumption of political news but not in popular - science articles. Borrowing the perspective of persuasion research, when it comes to the dissemination of political fact - checking, the recipient factor seems to be as important as the communicator and information factors, or even more important (O’Keefe, 2002:211). Therefore, this difference in results may also be due to the difference in the nature of the reading text. As emphasized in many studies, many measures to correct false information are effective, but political information is a unique type of information that is difficult to correct easily (Amazeen et al., 2016; Bode & Vraga, 2015; Nyhan & Reifler, 2010).

This result also has practical significance. On the one hand, the experiment proves that content labels with two valences can produce the expected nudging effects on individuals' information perception. This indicates that in platform practice, both error suppression and truth promotion should be carried out as two equal - weight governance paths. Governance does not mean blindly negative management; it can also take positive actions to promote the spread of truth, which is also a feasible governance idea. On the other hand, although the experiment verifies an obvious nudging effect, this effect may be limited by the subject group and the reading text, which further confirms the necessity of in - depth research on personalized nudging. A new proposition lies before us. When information nudging is effective but not for all users and all content, how exactly should policymakers consider its feasible advantages and infeasible limitations and integrate them into the future Internet content governance system? In different media - system climates, how much space is left for the soft governance tool of information nudging? These are all topics that future policy and regulation researchers can further explore.

6.2. The nudging Type Significantly Affects Information Interaction Willingness

The experiment uncovered that the warning label exerts a remarkable nudging effect in suppressing individuals' information interaction willingness, particularly the willingness to forward. Conversely, the certification label does not possess such a conspicuous enhancing nudging effect; it merely demonstrates a relatively notable promotion effect on the willingness to like.

This finding aligns with previous research results regarding fact - warning labels and the willingness to share. Concerning this effect, some scholars attribute it to individuals' loss emotions. They posit that the willingness to share information is regulated by cold cognition. When information is presented within a refuting or loss - narrative framework, it activates individuals' negative emotions, thereby diminishing their inclination to act impulsively (Taber & Lodge, 2006). Additionally, some scholars ascribe this effect to the outcome of the redistribution of attention resources. They contend that the reduction in the willingness to share caused by warning labels is mainly manifested in creating cognitive friction. That is, it prompts users to pause in the rapid - paced consumption rhythm of browsing infinite information flows and redirect their attention resources to the process of evaluating information quality, thus reducing the willingness to share false information, as people tend to share true information on social media (Pennycook et al., 2021). Irrespective of the explanation, it is acknowledged that warning labels can significantly decrease information participation and restrict the likelihood of the re - spread of false information. However, the experiment failed to detect a similar enhancing nudging effect for the certification label. In other words, the experiment did not find that the certification label can significantly boost individuals' information - sharing willingness, which is inconsistent with existing research conclusions (Aruguete et al., 2023). This might be because, in comparison to not sharing / not forwarding,sharing / forwarding is a behavior - decision - making process that is more influenced by diverse factors. Sharing is a behavior that demands more motivation to initiate than not sharing. It could be due to social motives, platform - usage habits, and so on (Oh & Syn, 2015). Simply put, an individual may decide not to forward a piece of information because it is untrue, yet it is challenging to decide to forward a piece of information solely because it is true. Therefore, the certification label cannot straightforwardly achieve the expected truth - promotion effect. It requires the addition of other motivational incentives to effectively increase the probability of the re - spread of true information by users within the platform context. As proposed in the research of Trifiro and Gerson (2019), the difficulty of nudging different users' behaviors varies. Compared with active users (who are fond of commenting, liking, and sharing content on social platforms), it is more arduous to enhance the sharing willingness of passive users (who dislike commenting, liking, and sharing content on social platforms). nudging needs to take individual characteristics into more consideration. The certification label has a distinct promoting nudging effect on the willingness to like information, indicating that the certification label is not entirely ineffective for information interaction willingness and truth - promotion governance. As a social - public and popularity indicator, as well as an algorithm - calculation indicator, the number of likes can potentially rectify individuals' information perception in the foreground and can also be integrated into the platform's algorithm framework as a traffic indicator in the background to facilitate the push and exposure of true information (Bode et al., 2020). Hence, the certification label can also indirectly contribute to the re - spread of true information, albeit with an effect less pronounced than that of the warning label.

The practical implication of this result is that platform managers need to treat the two types of content labels, error - suppression and truth - promotion, differently. Although both can produce a nudging effect, the error - suppression content label has a more evident nudging effect on behavior suppression. In other words, to influence individuals' information - sharing willingness, it is more effective to inform users that the information is subjective and biased rather than objective and of high quality. To achieve the same behavior - promoting nudging effect, the truth - promotion content label needs to be more customized according to users' actual situations, flexibly incorporating various incentive elements to more effectively create a virtuous communication scenario for the secondary and multiple dissemination of truth through labels.

6.3. The nudging Type Significantly Affects Brain Alpha - Wave Activity

Previous research predominantly concentrated on the effects of nudging at the behavioral level rather than the cognitive level. This is chiefly because scholars lacked research tools to meticulously examine the cognitive - processing process. They generally regarded behavior as the external manifestation of cognition and thus focused on behavioral changes in a rather general way. This experiment endeavors to utilize new research tools to meticulously explore the changes in individuals' implicit and micro - level cognitive - processing processes during information nudging.

The experiment revealed that the most prominent effect of information nudging lies in its impact on brain Alpha - wave activity. The power spectral density of the Alpha band in the warning - label condition was significantly higher than that in the no - label condition and the certification - label condition. Existing literature commonly posits that the enhancement of Alpha - band activity is associated with cognitive complexity (Borghini et al., 2014). Consequently, this finding indicates that the warning label can evoke stronger cognitive activity and complexity in individuals, attracting them to allocate more cognitive resources to information processing and inhibiting the occurrence of other cognitive activities unrelated to information processing, thereby enhancing the depth of cognitive processing. From the perspective of brain activity, this finding may imply that the nudging effect of the warning label might not be simply a result of activating individuals' heuristic system (System 1), but is more likely to be exerted through activating individuals' deliberative system (System 2). That is, the warning label may trigger individuals' analytical thinking for careful deliberation. Hence, the cognitive complexity under the cue of this label is higher, which validates the previous speculation regarding the action mechanism of information nudging. Scholars believe that the warning label represents a form of cognitive friction. Prompted by the warning label, users slow down the pace of information processing and redirect their limited attention to evaluating information quality, thus facilitating in - depth information processing (Pennycook et al., 2020). Moreover, the experiment discovered that the power spectral density of the Alpha band in the certification - label condition was nearly identical to that in the no - label condition, suggesting that the certification label neither reduces individuals' cognitive complexity nor deepens their cognitive processing, and has a minimal impact on individuals' cognitive - processing process. Therefore, it can be reasonably conjectured that the changes in individuals' information credibility perception and information interaction willingness induced by the certification label may be more attributable to the cognitive inertia of heuristic thinking. It cannot deepen individuals' information - processing degree per se and is more likely to exert the nudging effect by relying on individuals' heuristic system (System 1) (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972). In summary, the results of exploring brain activity from the perspective of cognitive neuroscience can be mutually corroborated with the aforementioned behavioral results. We can further expound that the impact of the warning label in information nudging on individuals' cognition and behavior is more likely to be the outcome of analytical thinking, achieved by enhancing the depth of individuals' information processing, while the impact of the certification label is more likely to be the result of heuristic thinking, realized by cueing to initiate individuals' information - processing inertia. However, this is merely a preliminary exploration of brain activity, and there remains ample research space to explore the cognitive - processing process from the perspective of brain activity in the future.

This result also holds practical significance. It provides a more profound understanding of the action mechanism of information nudging from the perspective of brain activity, uncovering that error - suppression and truth - promotion may activate different thinking systems and cognitive modes in individuals. This indicates that the effect of information nudging not only lies in providing and disclosing information details themselves but also in how to guide individuals to conduct cognitive processing, further emphasizing the necessity of considering individuals' cognitive processes in information design. Understanding how different types of information nudging influence individuals' cognitive processes is conducive to designing more effective information - presentation methods. For instance, when managers need individuals to rapidly respond to information as expected, they can make more use of certification - type content labels to promote individuals' thinking inertia and induce behavior. When managers require individuals to think carefully and deepen the depth of information processing, they can adopt refuting - loss - type warning - label frameworks to induce individuals' analytical thinking and improve individuals' behaviors and decisions. Meanwhile, this result also alerts platforms to the potential risks that information nudging may entail in practice. Although the warning label can guide individuals to conduct more in - depth cognitive processing and promote cognitive complexity, if misused, it may also lead to individuals' over - interpretation or misinterpretation of information, imposing unnecessary cognitive burdens. Therefore, when applying information nudging in practice, it is essential to fully consider individuals' cognitive characteristics and situational factors to ensure the effectiveness and safety of information nudging. Only by fully taking into account individuals' cognitive processes and characteristics can more effective information - nudging strategies be devised to specifically improve individuals' behaviors and decisions, thereby bringing more positive impacts to individuals and society.

6.4. The Influence of Awareness of the nudging Subject Is Not Significant

Contrary to expectations, the experimental results show that the awareness of the nudging subject has no significant impact on individuals' information credibility perception and information interaction willingness. That is to say, whether users know that the content labels are issued by the platform's self - built verification resources does not affect the nudging effect of the content labels themselves.

In existing research on the sources of fact - checking, scholars generally assume and confirm that the source of fact - checking (i.e., who initiates the fact - checking) has an impact on the effect of fact - checking work. There is a large body of debate on who can be the arbiter of truth and who users tend to believe is the arbiter of truth (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). However, these studies have not reached a conclusion on whether a certain type of fact - checking is more effective than others (Moon et al., 2022). Some recent studies have found that the credibility of fact - checking work by human experts is on the decline. Users sometimes doubt the third - party independence of these expert groups (Su, 2021). The recent prevalence of anti - intellectualism also indicates the general public's skeptical and distrustful attitudes and trends towards intellectuals and various experts (Merkley, 2020). Therefore, the effectiveness of fact - checking labels can also be affected. Before the experiment, the author hypothesized that the different implementation contexts of fact - checking at home and abroad might also affect the effectiveness of fact - checking labels. Domestic users often do not recognize the professionalism and authority of the platform's content determination and even frequently challenge and refute the content determination results of platform auditors (Einwiller & Kim, 2020). The experimental results show that when the platform serves as the source of fact - checking, it does not affect the nudging effect and governance effectiveness. In other words, the platform is an acceptable, professional, and authoritative information auditor for users. Scholars have always been exploring the dilemma of platform governance in fact - checking. While the power of the platform is regulated, it is difficult for the platform to complete all information audits on its own. This has led to misunderstandings about platform governance in the outside world (De Kloet et al., 2019). The first misunderstanding is that the platform does nothing. Due to the platform's dual role as both a rule - maker and an executor, some people believe that it is difficult for the platform to conduct self - supervision, or they question the publicity of its rules and the effectiveness of its implementation, and misunderstand the platform as the culprit of the spread of false information. The second misunderstanding is that the platform or society can eliminate all false information with one click. The governance advantage of the platform lies in using artificial intelligence technology to improve the efficiency of information processing to a certain extent, such as realizing information early warning, personalized distribution, and accurate labeling. The accurate judgment of false information requires the joint efforts of the government, professional media, users, and other parties. It is difficult for the platform to achieve this on its own. The third misunderstanding is that the platform is the root source of false information. In fact, false information existed before the Internet platform. Currently, false information or rumors are widespread, and many false information spreads across platforms. It is difficult to attribute the occurrence of false information to a certain platform or subject. Multi - subject and multi - platform joint governance is needed. Therefore, objectively evaluating the governance ability of the platform is also a difficult problem in clarifying the allocation of rights and responsibilities in the governance of false information. On the one hand, we should not rely too much on the platform; on the other hand, we should not completely deny the role of the platform.

This leaves another research topic: How should we view the possible impact of the information nudging subject on its nudging effect? Given that human experts may have more or less biases and limitations when serving as the main body of fact - checking work, new sources such as artificial intelligence and crowdsourced collective intelligence have gradually become alternative fact - checkers (Margolin et al., 2017). Some studies have found that artificial intelligence is considered a more objective and accurate source of information than humans (Sundar, 2020), especially when the content is politically controversial, fact - checking by artificial intelligence can bring better governance effects than human fact - checking (Edwards et al., 2019). In addition, some studies have found that the crowdsourced collective wisdom formed through user participation has a more effective false - information correction effect and can effectively enhance information credibility (Huang & Sundar, 2020). However, some studies have also found that the crowdsourced clues of fact - checking information do not affect individuals' judgment of facts (Bode et al., 2020). Regarding these mixed research results, this chapter also hopes to inspire more research to engage in exploring the generation mechanism of information nudging and the impact of the subject on its nudging effect. What are the different governance effects of the three different information nudging mechanisms, namely algorithm - identification, authority - determination, and user - participation? How should the combination strength and space of these mechanisms be arranged to achieve the optimal effect? These are all issues that urgently need to be addressed and explored in the future.

VII. Summary

This study mainly employed an experimental method combined with cognitive - neuroscience measurement tools. Among a sample of 100 subjects, by setting two nudging scenarios (fact - warning label vs. fact - certification label) and two nudging awareness conditions (aware of the nudging subject vs. unaware of the nudging subject), the effect of information nudging was investigated in the platform context, mainly answering three questions:

(1) How does information nudging affect individuals' information credibility perception?

(2) How does information nudging affect individuals' information interaction willingness?

(3) How does information nudging affect the cognitive - processing activities in individuals' brains?

In summary, the following important conclusions were drawn:

First, the valence of content labels (whether warning or certification) further influences individuals' judgment of information credibility. This indicates that in platform practice, both error - suppression and truth - promotion should be carried out as two equal - weight governance paths. Governance does not mean blindly negative management; it can also take positive actions to promote the spread of truth.

Second, the valence of content labels has different nudging effects on individuals' information interaction willingness. The warning label has a significant nudging effect of suppressing individuals' information interaction willingness, especially the willingness to forward. However, the certification label does not have such a significant enhancing nudging effect and only has a relatively obvious promoting effect on the willingness to like. This enlightens platform managers to treat the two types of content labels, error - suppression and truth - promotion, differently. For example, to influence individuals' information - sharing willingness, it is better to use a warning label rather than a certification label.

Third, whether users know that the content labels are issued by the platform's self - built verification resources does not affect the nudging effect of the content labels themselves. This further demonstrates that even in different media systems, information nudging still has the governance potential to be implemented in the platform context. Users recognize and accept the platform as the content - review party to rate, evaluate, and prompt the content quality.

Fourth, the most significant effect of information nudging is on brain Alpha - wave activity. The power spectral density of the Alpha band in the warning - label condition is significantly higher than that in the no - label condition and the certification - label condition. This indicates that the warning label significantly enhances individuals' cognitive - processing depth and cognitive complexity, providing a deeper understanding of the action mechanism of information nudging from the perspective of brain activity. It shows that the effect of information nudging lies not only in activating heuristic thinking but also in inducing analytical thinking.

References

- Amazeen, M.A.; Thorson, E.; Muddiman, A.; et al. Correcting political and consumer misperceptions: The effectiveness and effects of rating scale versus contextual correction formats. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2016, 95, 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aruguete, N.; Bachmann, I.; Calvo, E.; et al. Truth be told: How “true” and “false” labels influence user engagement with fact-checks. New Media & Society 2023, 14, 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication 2015, 65, 619–638. [Google Scholar]

- Chan JC, K.; O'Donnell, R.; Manley, K.D. Warning weakens retrieval-enhanced suggestibility only when it is given shortly after misinformation: The critical importance of timing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 2022, 32, 375–391. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K.R. The neurology of negation; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.; Leslie, K.R.; García-García, M.; et al. How advertisers can keep mobile users engaged and reduce video-ad blocking. Journal of Advertising Research 2018, 58, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker UK, H.; Lewandowsky, S.; Chadwick, M. Can corrections spread misinformation to new audiences? Testing for the elusive familiarity backfire effect. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2020, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einwiller, S.; Kim, S. How online content providers moderate user-generated content to prevent harmful online communication: An analysis of policies and their implementation. Policy & Internet 2020, 12, 184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom, P.D.; Lai, C.K. The selective communication of political information. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2020, 12, 789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Humprecht, E. How do they debunk “fake news”? A cross-national comparison of transparency in fact checks. Digital Journalism 2019, 8, 310–327. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, L.S.; Boles, D.B. The effect of symbols on warning compliance. Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting 1990, 34, 984–987. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness. Cognitive Psychology 1972, 3, 430–454. [Google Scholar]

- Kaup, B.; Ludtke, J.; Zwaan, R.A. Processing negated sentences with contradictory predicates: Is a door that is not open mentally closed? Journal of Pragmatics 2006, 38, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, G. The nudging effect of AIGC labeling on users’ perceptions of automated news: Evidence from EEG. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, R. “Let’s check it seriously”: Localizing fact-checking practice in China. International Journal of Communication 2022, 16, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nekmat, E. Nudge effect of fact-check alerts: Source influence and media skepticism on sharing of news misinformation in social media. Social Media + Society 2020, 6, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior 2010, 32, 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Oeldorf-Hirsch, A.; Schmierbach, M.; Appelman, A.; et al. The influence of fact-checking is disputed! The role of party identification in processing and sharing fact-checked social media posts. American Behavioral Scientist 2023, 27, 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, D.J. Persuasion: Theory and research; SAGE, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Otis, A. The effects of transparency cues on news source credibility online: An investigation of ‘opinion labels’. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 2022, 14, 488–492. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Kee, K.F.; Shin, E.Y. The nudging effect of accuracy alerts for combating the diffusion of misinformation: Algorithmic news sources, trust in algorithms, and users’ discernment of fake news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 2023, 67, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Thorson, K. Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. Journal of Communication 2017, 67, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, J.B. Fact-checkers as entrepreneurs. Journalism Practice 2018, 12, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, B.E.; De Zúñiga, H.G. What’s next? Six observations for the future of political misinformation research. American Behavioral Scientist 2019, 65, 277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z. Reducing younger and older adults’ engagement with COVID-19 misinformation: The effects of accuracy nudge and exogenous cues. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2023, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

The Distribution of Sample Sizes under Each Experimental Condition.

Table 1.

The Distribution of Sample Sizes under Each Experimental Condition.

| |

No identification is allowed in the main text |

Authentication identification in the main text |

No identification (control group) |

| Be informed during the identification |

N = 19 |

N = 18 |

N = 18 |

| Be uninformed during the identification process |

N = 19 |

N = 18 |

Table 2.

Perception of information credibility under various experimental conditions(M ± SD).

Table 2.

Perception of information credibility under various experimental conditions(M ± SD).

| |

No identification is allowed in the main text |

Authentication identification in the main text |

No identification (control group) |

| Be informed during the identification process |

3.07 ± 0.58 |

3.96 ± 0.56 |

3.48 ± 0.61 |

| Be uninformed during the identification process |

3.02 ± 0.50 |

3.94 ± 0.56 |

Table 3.

The willingness to interact with information under various experimental conditions(M ± SD).

Table 3.

The willingness to interact with information under various experimental conditions(M ± SD).

| |

No identification is allowed in the main text |

Authentication identification in the main text |

No identification (control group) |

| Be informed during the identification process |

3.05 ± 0.52 |

3.76 ± 0.56 |

3.46 ± 0.61 |

| Be uninformed during the identification process |

3.07 ± 0.68 |

3.81 ± 0.54 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).