Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

Design

| ‘Cronbach alpha | |

|---|---|

| Brand awareness | 0.78947 |

| Investments risks & CSR | 0.8824 |

| Brand preferences & culture | 0.88725 |

| Perceptions | 0.88235 |

| Brand image | 0.9245 |

| Brand reputation | 0.83768 |

| Brand communication | 0.92308 |

| Brand equity | 0.917 |

| Sustainability | 0.882245 |

3. Background Literature

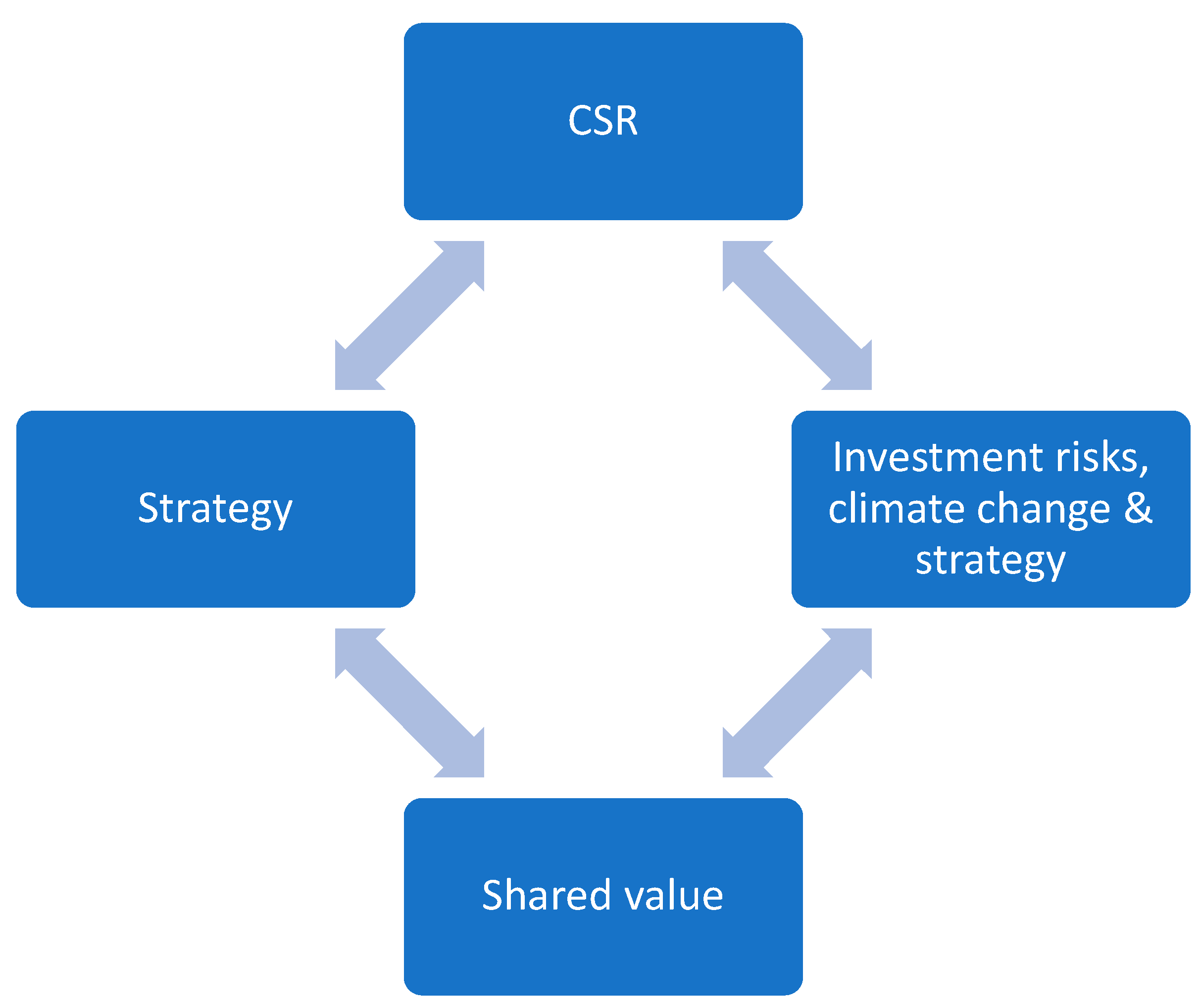

3.1. Theoretical Framework

- Investment risks, climate change & strategy:

- Research Question(s) and Hypotheses

3.2. Propositions & Frame work for Hypothesis:

3.3. Formulations & Hypothesis:

3.3.1. Hypotheses:

- Corporations can achieve optimal utilization of resources by engaging n ‘CSR, and embracing as an investment risks against wasteful expenditures, such as seeking legal redress against ligations, activism and motivations against careless activities from climate change events.

- As an investment risks and the manner being embedded into the ‘CSR strategy of an organization, a reputable brand can be built and translate to a brand equity.

- A sustainable business model can be achieved by adopting ‘CSR as a strategic tool from investment risks and a derivative of operational efficiency, effective organizational and financial performances.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Reliability Test & Validity

| ‘Cronbach alpha | ‘Composite reliability | ‘AVE | ‘Factorial loadings ‘** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand awareness | 0.78947 | 0.87200 | 0.623 | 0.7893 |

| Images & brand reputation | 0.83768 | 0.84100 | 0.640 | 0.790 0.825 |

| CSR. brand & image | 0.84906 | 0.88100 | 0.79725 | 0.8928 |

| Image, preferences & brand | 0.92308 | 0.93500 | 0.78325 | 0.8850 |

| ‘investment risks, CSR & brand * | 0.88720 | 0.95600 | 0.84375 | 0.9185 |

| ‘brand preferences & perceptions | 0.98640 | 0.96700 | 0.8785 |

0.93728 |

| Investment asks from litigation | 0.8225 | 0.88825 | 0.8821 | 0.9250 0.8982 0.9224 0.9224 |

| Operational efficiency | 0.9978 | 0.9988 | 0.8823 | 0.8900 |

| Financial stability & performances | 0.8978 | 0.8254 | 0.7224 | 0.8490 0.8882 |

| CSR, brand & reputation | 0.97820 | 0.9824 | 0.8825 | 0.9801 0.9394 |

| CSR, Image & brand reputation | 0.92245 | 0.92556 | 0.8254 | 0.9225 0.9085 0.8908 |

| Consumer preferences & brand image | 0.84906 | 0.8524 | 0.7234 | 0.8505 |

| Image & brand communication | 0.8225 | 0.89724 | 0.75524 | 0.8690 |

| ‘Brand, inclinations, media & culture | 0.89640 | 0.938 | 0.7900 | 0.8888 0.8824 |

| ‘Brand, lifestyles, culture & interactions | 0.92310 | 0.94000 | 0.79225 | 0.8001 0.825 0.8824 |

| Communication, brand, preferences & culture | 0.82502 | 0.8725 | 0.79234 | 0.8901 |

| ‘Parameter or variables | ‘Indicators | ‘Estimate | ‘T value |

|---|---|---|---|

| - perception of consumers and employees from reputation - perception from awareness, communication & message - perception of effectiveness from experiences & activities or engagement - perception of image - perception from association, culture & link or lifestyles |

P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 |

0.770 0.728 0.625 0.725 0.885 |

4.225 5.225 3.602 9.772 6.825 |

| - investment risks from climate changes \& events - investment risks from litigation - investment risks & incentives - investment risks, resources & incentives |

R. 1 R 2 R. 3 R. 4 |

0.326 0.424 0.238 0.221 |

4.880 6.824 6.200 2.594 |

| - sustainability and performances - operational efficiency and performances - operational efficiency, performances & effectiveness - enhanced financial performances - future growth and sustainability |

S 1 S 2 S 3 S4 S5 |

0.384 0.644 0.625 0.724 0.86 |

9.224 8.225 12.829 6.24 7.24 |

| Brand reputation - investment risks | 0.224 | 12.40 | |

| Brand equity - investment risks | 0.625 | 8.25 |

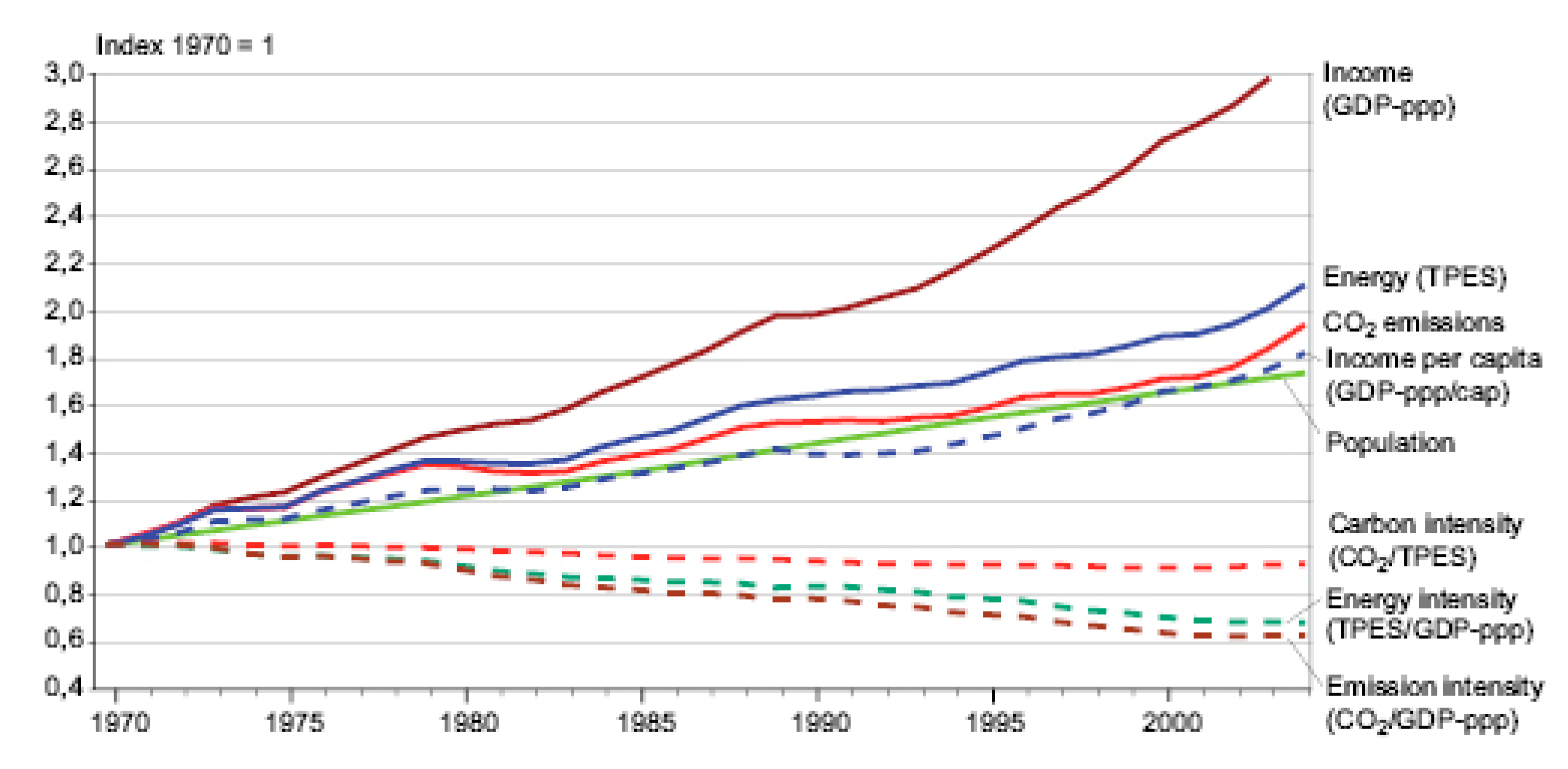

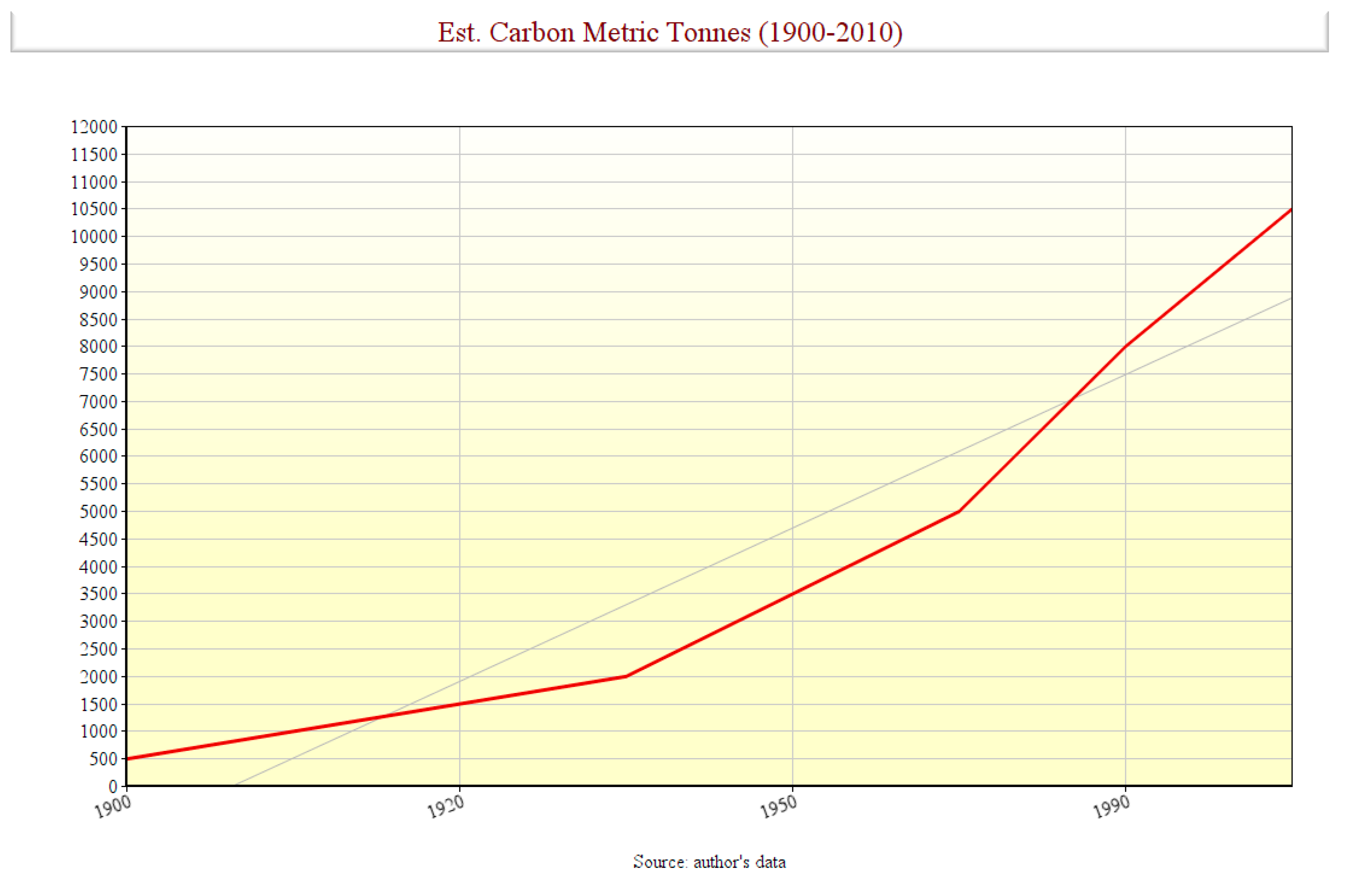

4.2. Climate Change, Mitigation, Models, Projections and Litigation

4.2.1. Climate Change: ’Combating Climate Changes, Stabilization & Mitigation Efforts! ‘*

The ultimate or prime objective of this Convention … is to achieve … stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic or man-made interference with the climate system and manifestations that could be seen.(UNFCCC (UN Report, 1992)

4.3. Qualitative Results on Consumer’s Perception: ‘Themes & Analysis:

- ‘Responses:

- Themes:

6. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| CSR: | Corporate social responsibility |

| ‘BE: | Brand equity |

| ‘BR: | Brand relationship |

| ‘CR: | Corporate responsibility or reputation |

| ‘ESG: | Environment, society & governance |

| ‘EU: | European Union |

| ‘UNFCCC: | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| ‘IPCC: | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ‘WOM: | Wood of mouth |

| CV: | Coefficient of variance or variations |

| z – tabulated: | tab) and z – calculated: cal) |

| t-cal: | calculated t-test statistics from formula or expression |

| tc: | critical value from the t-test |

| μ: | mean or sample mean |

| μ0: | hypothesized or drawn population mean |

| ‘AVE: | Average Variance Extracted |

| S.D: | Standard deviation |

| SEM: | Structural equation modeling |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1.1 Observations and Ratings: ‘Based on Likert Ratings (1 – 5)

- ‘N.B:

| (a) Summary and Statistics | |||||

| N | Mean | Std. dev., | Std. err | ||

| Group 1 | 50 | 4.758 | 0.825 | 0.1069 | |

| Group 2 | 75 | 4.895 | 0.423 | 0.0724 | |

| ‘Source: ‘Author’s draft from present study, 2024. | |||||

| (b): ANOVA Summary & Statistics | |||||

| ‘Source | ‘Df | SS | MS | F | P |

| Between Groups | 1 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.6001 | 0.445 |

| Within Groups | 124 | 3.4995 | 0.125 | ||

| Total | 125 | 3.5745 | |||

| p -value: 0.445. F: 0.6001. ‘Source: ‘Author’s draft from present study, 2024 | |||||

Appendix A.1.2 Extrapolated/Simulation: ‘A Simulated/Extrapolated Responses and Illustrations of Consumers Responses based on Perceptions of Organizations– Business Models Attributes from ‘CSR & Features from the Research Questions, Interview and Survey

Notes

- I.

- Shanks & Roegner. (2007). Aquatic Climate Change Adaptation Services Program-Pacific ……publications.gc.ca>collection_2016>mpo-df0>Fs97-4-3049-eng

- II.

- III.

- ‘https://www.ejiltalk.org/a-new-classic change in climate-change-litigation: the –dutch-supreme court-decision—in-the-urgenda-case/

References

- Adewole, O. Translating brand reputation into equity from the stakeholder’s theory: an approach to value creation based on consumer’s perception & interactions. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility. 2024, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R. R. , Vveinhardt, J., Warraich, U. A., Hasan, S. S. U., & Baloch A. Customer Satisfaction & Loyalty and Organizational Complaint Handling: Economic Aspects of Business Operation of Airline Industry. Inzinerine Ekonomik–Engineering Economics. 2020, 31, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R. R. , Hussain, S., Pahi, M. H., Usas, A., & Jasinskas, E. Social Media Handling and Extended Technology Acceptance Model (ETAM): Evidence from SEM-Based Multivariate Approach. Transformation in Business & Economics. 2019, 18, 246–271. [Google Scholar]

- Alafeshat, R. , & Tanova, C. Servant leadership style and high-performance work system practices: Pathway to a sustainable jordanian airline industry. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G. , Sajjad, I., Elahi, N. S., Farooqi, S., & Nisar, A. The influence of prosocial motivation and civility on work engagement:The mediating role of thriving at work. Cogent Business and Management. 2018, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Adewole O, Fajemiroye J.A and Esholomo J.O. “An Assessment and Model for Dynamic Behaviour and Climate Change Mitigation Action Plan” Published in International Journal of Trend in Research and Development (IJTRD) 2018, 5. http://www.ijtrd.com/papers/IJTRD16758.pdf.

- Aguilera, R. , Rupp, D., Williams, C. and Ganapathi, J. ‘Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations.’ Academy of Management Review. 2007, 32, 36–863. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H. and Glavas, A. ‘What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda.’ Journal of Management. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Gary, and Philip Kotler (2008). Principles of Marketing, 12th ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ, Pearson Educational Inc.

- Brooks, C.; Oikonomou, I. The effects of environmental, social and governance disclosures and performance on firm value: A review of the literature in accounting and finance. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, M. C. , and Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics. 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J. In whose Name? The Accountability of Corporate Social Responsibility: Development in Practice. 2005, 15, 362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bendixen, M. , & Abratt, R. Corporate identity, ethics and reputation in supplier-buyer relationships. Journal of Business Ethics. 2007, 76, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbeim, R. E. Business ethics and corporate social responsibility: Defining an organization’s ethics brand. Vital Speeches of the Day. 2006, 72, 501–503. [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, T. Corporate gains: Corporate social responsibility can be the strategic engine for long-term corporate profits and responsible social development. Alternatives Journal 2005, 31, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J. What to do when stakeholders matter. Public Management Review 2005, 6, 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.L.; Wicks, A.C.; Kotha, S.; Jones, T.M. Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 488–506. [Google Scholar]

- Clipa, A.-M. , Clipa, C.-I., Danilet, M., & Andrei, A. G. Enhancing sustainable employment relationships: An empirical investigation of the influence of trust in employer and subjective value in employment contract negotiations. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, C. (2018). Introduction to Multivariate Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Camilleri, M.A. Corporate sustainability and responsibility: creating value for business, society and the environment, Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility (AJSSR), ISSN 2365-6417, Springer, Cham 2017, 2, p. 59-74. [CrossRef]

- Çifci, S. , Ekinci, Y., Whyatt, G., Japutra, A., Molinillo, S., and Siala, H. A cross validation of consumer-based brand equity models: driving customer equity in retail brands. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3740–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, A. F. , Rogerson, J.M., & Rampedi, I. Integrated reporting vs. sustainability reporting for corporate responsibility in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. 2015, 29, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. B. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organizational Dynamics 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. B/. & Buchholtz, A.K. (2011). Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management. Australia: Thomson South-Western.

- Crane, A. & Kazmi, B.A. Business and Children: Mapping Impacts, Managing Responsibilities. Journal of Business Ethics. 2010, 91, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. B. (2008). A history of corporate social responsibility: concepts and practices. In A. M. Andrew Crane, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 19–46). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 39-48.

- Carroll, A.B. A three dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A. , McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., and Siegel, D. S. (2008). “The corporate social responsibility agenda,” in The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, eds A. McWilliams, D. E. Rupp, and D. S. Seigel (Oxford: Oxford University Press). [CrossRef]

- FATMAWATI1, I. , & FAUZAN2 N. Building Customer Trust through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Effects of Corporate Reputation and Word of Mouth Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business. 2021, 8, 0793–0805, Print ISSN: 2288-4637 / Online ISSN 2288-4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Frynas, J.G. , & Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics, the environment & responsibility. 2016, 25, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein, M. (2013). The Reagan-Thatcher revolution. https://www.dw.com/en/the-reagan-thatcher-revolution/a-16732731. Accessed 9 Nov 2018.

- Ferrell, O.C. , and Michael D. Hartline. (2011). Marketing Strategy. Msason, OH: South – Western Cengage Learning.

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, B.S; et al. (2007). “Issues related to mitigation in the long term context”. In B. Metz et al. eds., Climate change, 2007: Multi - guide Contribution of Workshop Group 111 to the Forum. Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved, 20 May, 2007.

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. , and Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman M (1970) The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine (September 13), 32–33.

- Gavana, G.; Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A.M. Related party transactions and earnings management: The moderating effect of esg performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchi, M. , Vonthron, A.-M., & Ghislieri, C. Perceived job insecurity and sustainable wellbeing: Do coping strategies help? Sustainability. 2019, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P. C, Merrill C.B, Hansen J.M. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: an empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg Manag J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Management Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, A. and Piderit, S.K. ‘How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees.’ The Journal of Corporate Citizenship. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gotsi, M. , and Wilson, A.M. Corporate reputation: seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, K. , Arshed, N., Yazdani, N., and Munir, M. Motivating business towards innovation: a panel data study using dynamic capability framework. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P. “Strategic corporate responsibility: a theory review and synthesis”, Journal of Global Responsibility 2018, 9, 388–414. [CrossRef]

- Ifada, L. M. , Ghozali, I., & Faisal. Corporate social responsibility, normative pressure and firm value: Evidence from companies listed on Indonesia stock exchange. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 2021, 1194, 390–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanović-Đukić, M. Podsticanje društveno odgovornog poslovanja preduzeća u funkciji pridruživanja Srbije EU. Ekonomske teme 2011, 49, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S. , Rosenberg, S., and McCabe, B. Corporate social responsibility behaviors and corporate reputation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Jain, P.K.; Rezaee, Z. Value-relevance of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from short selling. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2016, 28, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. and Neville, B. ‘Convergence vs divergence in CSR in developing countries: An embedded multi-layered institutional lens.’ Journal of Business Ethics. 2011, 102, 599–621. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. ESG disclosure and Firm performance: A bibliometric and meta analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Finance. 2022, 61, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khediri, K. B. CSR and investment efficiency in Western European countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2021, 28, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusanova, R. , Choi, S.B., & Kang, S.-W. Sustainable workplace: The moderating role of office design on the relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational citizenship behaviour in Uzbekistan. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. , Kim, J., Mmarshall, R., & Afzali, H. Stakeholder influence, institutional duality, and csr involvement of mnc subsidiaries. journal of business research. 2018, 91, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, N. Primena Principa poslovanja i prava dece u strategiji društveno odgovornog poslovanja preduzeća u Srbiji. Sociologija 2017, 59, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutti, R. & Hegerl, G. The equilibrium sensitivity of the earth’s temperature to radiation changes. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 735–743. [Google Scholar]

- López-González, E. , Martínez-Ferrero, J., and García-Meca, E. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: a contingency approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1044–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. , and Lu, W. Corporate social responsibility, firm performance, and firm risk: the role of firm reputation. Asia Pacific J. Account. Econ. 2019, 27, 2991–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Koh, L. The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , Graves, S.B., & Waddock, S. Doing good does not preclude doing well: Corporate responsibility and financial performance. Social Responsibility Journal. 2018, 14, 764–781. [Google Scholar]

- Morejón, B. R. G. , & Lorenzo, A.F. Responsabilidad social empresarial y competitividad en las clínicas de salud privadas de Quito, Ecuador. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo. 2020, 8, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy, John, and Tom Butler. “A Critical Realist Method for Applied Business Research.” Journal of Critical Realism. 2018, 17, 160–175. [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. P. , Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A. and Siegel, D. S. ‘Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future.’ Personnel Psychology. 2013, 66, 805–824. [Google Scholar]

- Mallah, M. F. , & Jaaron, A.A. M. An investigation of the interrelationship between corporate social responsibility and sustainability in manufacturing organisations: An empirical study. International Journal of Business Performance Management. 2021, 22, 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Ortega, O. , & Wallace, R. Business, Human Rights and Children: The Developing International Agenda. Denning Law Journal 2013, 105-128.

- Morsing, M. and Perrini, F. ‘CSR in SMEs: do SMEs matter for the CSR agenda?’. Business Ethics: A European Review. 2009, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, D. , & Moon J. ‘‘Implicit’ and ‘Explicit’ CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility’. Academy of Management Review. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I. , & Ferrell, O.C. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and human benefits. Journal of the Academy Management Science. 2005, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I. & Ferrell, O.C, & Ferrell, L. A Stakeholder Model for Implementing Social Responsibility in Marketing. European Journal of Marketing. 2005, 39, 956–977. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I. and Ferrell O.C. ‘Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework’. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Michelon, G. , Boesso, G. & Kumar, K. Examining the link between strategic corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: An analysis of the best corporate citizens. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2013, 20, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A. & Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. P. , Munilla, L.S., & Darroch, J. The role of strategic conversations with stakeholders in the formation of corporate social responsibility strategy. Journal of Business Ethics. 2006, 69, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M. and Perrini, F. ‘CSR in SMEs: do SMEs matter for the CSR agenda?’. Business Ethics: A European Review. 2009, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, A.C.; Rezaee, Z. Business sustainability factors and stock price informativeness. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101688. [Google Scholar]

- Newburry, W. , Deephouse, D. L., and Gardberg, N. A. (2019). “Global aspects of reputation and strategic management,” in Global Aspects of Reputation and Strategic Management, eds D. Deephouse, N. Gardberg, and W. Newburry (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited). [CrossRef]

- Orviz Martínez, N. , Cuervo Carabel, T., & Arce García, S. Review of scientific research in ISO 9001 and ISO 14001: A bibliometric analysis. Cuadernos de Gestión. 2021, 21, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo López, O. , Vargas Barrera, L.., & Suárez Giraldo, K. Determinación de brechas estructurales en la integración de la responsabilidad social en empresas del sector textil-confección de la región Centro-Sur de Caldas. Revista Ciencias Estratégicas. 2016, 24, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M. , Siegel, D.S. and Waldman, D. A. ‘Strategic corporate social responsibility and environmental sustainability.’ Business and Society. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M. and Swanson, D. 2006. ‘Socially responsible human resource management: Charting new territory.’ In J. Deckop (Ed.), Human Resource Management Ethics: 3-25. Greenwich: IAP.

- Popkova, E. , Delo, P., & Segi, B. S. Corporate social responsibility amid social distancing during the COVID-19 crisis: BRICS vs. OECD countries. Research in International Business and Finance. 2021, 55, 101315. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. , & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 1 – 17 (Accessed January-February, 2011).

- Porter, M.E. ; & Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Revuelto-Taboada, L. , Canet Giner, M.T., & Balbastre-Benavent, F. High-commitment work practices and the social responsibility issue: Interaction and benefits. Ustainability. 2021, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rettab, B. , and Mellahi, K. (2019). “CSR and corporate performance with special reference to the middle east,” in Practising CSR in the Middle East, eds B. Rettab and K. Mellahi (Berlin: Springer), 101–118. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R. , (2011). Does Corporate Social Responsibility Increase Profits? Retrieved from http://www.environmentalleader.com/2011/05/26/does-corporate-social-responsibility-increase-profits/.

- Suki, N. M. , and Suki, N. M. (2019). “Correlations between awareness of green marketing, corporate social responsibility, product image, corporate reputation, and consumer purchase intention,” in Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, eds Management Association and Information Resources (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Setzer., & Vanhala, (2019). Climate change litigation: A review of research on courts and litigants in climate governance. Wiley Online (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/wcc.580).

- Shao, D. , Zhou, E., Gao, P., Long, L., & Xiong, J. Double-edged effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee task performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating by role ambiguity and moderating by prosocial motivation. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulić, V. , & Pavlović, M. Corporate social responsibility in relations with social community: Determinants, development, management aspects. Ekonomika. 2018, 64, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salvini, G. , Dentoni, D., Ligtenberg, A., Herold, M., & Bregt, A. K. Roles and drivers of agribusiness shaping climate-smart landscapes: A review. Sustainable Development. 2018, 26, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. , and Thai, V.V. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction, relationship maintenance and loyalty in the shipping industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R. , Freeman, R.E., & Hockerts, K. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Scandinavia: An overview. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, Randy. Is Social Responsibility Good? Journal for Quality& Participation. 2010, 3, 13–17.

- Smith, J.; et al. Assessing dangerous climate change through an update of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ‘reasons for concern’. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 2009; 106, 4133–4137. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R. , Langer, M.E., Konrad, A., & Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, stakeholders and sustainable development I: A theoretical exploration of business-society relations. Journal of Business Ethics. 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S. H. & Mastrandrea, M.D. (2005) Probabilistic assessment of ‘dangerous’ climate change and emissions pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005, 102, 15-728–15-735. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, J. Managing in the post-managerialist era: Towards socially responsible corporate governance. Management Decision 2004, 42, 601–611. [Google Scholar]

- Tzempelikos, N. , and Gounaris, S. (2017). “A conceptual and empirical examination of key account management orientation and its implications–the role of trust,” in The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World, ed C. L. Campbell Berlin: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z. , Arslan, A., & Puhakka, V. Corporate social responsibility strategy, sustainableproduct attributes, and export performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2021, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations: 1992. Framework Convention on Climate Change, United Nations Conf. on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- UNFCCC (9 May 1992). United Nations Framework Convection on Climate Change, New York, archived from the original on 14 April 2005.

- UNFCC (25 October 2005). Sixth Compilation and Synthesis of initial national common actions from parties not included in Annex 1to the convention note by the Secretariat Executive Summary. Document code FCCC/SBI/2005/18, Geneva Switzerland: United Nations Office.

- UNFCCC. (2009). Copenhagen Accord (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). See http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/l07.pdf.

- Yadav, R. S. , Dash, S.S., Chakraborty, S., & Kumar, M. Perceived CSR and corporate reputation: The mediating role of employee trust. Vikalpa. 2018, 43, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Luo, S. Sustainable development, ESG performance and company market value: Mediating effect of financial performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadek, S. The Path to Corporate Responsibility. Harvard Business Review. 2004, 82, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).