1. Introduction

The introduction and ongoing development of injectable biostimulators in the field of aesthetic medicine has revolutionized skin rejuvenation and volume restoration.[

1] These materials, known for their ability to stimulate the neocollagenesis,[

2,

3] offer a minimally-invasive alternative to surgical procedures. Seeking natural results, a growing number of patients demand these treatments to promote skin tightening and volumization through collagen induction.[

4] Among the various collagen biostimulators available, Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA) is of great popularity both among aesthetic practitioners and patients as it has shown to be a particularly effective and long-lasting product.[

5] PLLA is a synthetic, biodegradable polymer that has a long and well-researched history of use in both medical and cosmetic applications.[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] Once injected, PLLA microparticles stimulate fibroblasts in the skin to produce new collagen, resulting in a gradual increase in skin thickness and firmness.[

5,

11] Thus, PLLA helps not only restore lost volume but also improve skin quality by enhancing the skin’s overall structural integrity.[

12]

In light of PLLA’s collagen-stimulating effects, it is logical to consider the architecture of the injected skin area. In fact, the skin's thickness, the amount of subcutaneous fat, and the overall dermal structure can vary significantly over the body.[

13] These differences suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach to PLLA concentration may not be optimal. Adjusting the concentration to align with the specific structural skin characteristics of the target area could theoretically enhance both the safety and effectiveness of the treatment.[

14]

The temples and neck, in particular, present unique challenges compared to mid-face or other facial areas in which the clinical efficacy and safety profile of PLLA injections have been extensively investigated in previous studies.[

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] The skin in the temples is relatively thin and is characterized by a sparse layer of subcutaneous fat, rendering it more susceptible to injection-related complications in general and product show in specific.[

20] Further, the intricate layered arrangement in this facial region requires an in-depth understanding of topographic anatomy to provide not only efficacious but also safe aesthetic treatments.[

21] Similarly, the neck has a complex anatomy with heterogenous thickness of the skin and underyling layers (e.g., subcutaneous fat, and decussating SMAS in the midline), predisposing for higher risks of adverse events such as nodule formation when treated with standard concentrations of collagen biostimulators. These skin differences call for a tailored approach when using PLLA in these regions to minimize the risks while maximizing aesthetic results.[

20] Given the unique challenges specific to these facial regions, evenly-spread injections of hyperdiluted PLLA employing a fanning technique seem to be a viable option to administer this product effectively.[

17,

21]

This study, therefore, aims to evaluate patient satisfaction and safety associated with injections of hyperdiluted PLLA in these specific areas. By prospectively analyzing treatment outcomes, we sought to determine whether this anatomically aligned approach could mitigate potential complications while delivering effective aesthetic results. Our insights can be leveraged by both patients and providers: For patients, understanding the safety and efficacy of hyperdiluted PLLA injections in the temples and neck can provide reassurance and inform their choices about aesthetic treatments. For injectors, the study offers valuable insights into how adjusting PLLA concentrations to suit the anatomical and structural nuances of each target area can help enhance treatment outcomes and reduce the risk of complications. By doing so, practitioners may achieve more consistent and satisfactory results, ultimately leading to higher patient satisfaction and better overall results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setup

This controlled prospective single-center study aimed to investigate the procedural safety and patient satisfaction following a single-session treatment of the temples and neck using the PLLA-based soft tissue filler Rennova Elleva® (Rennova, Goiânia, Brazil). The study was conducted between November 2023 to September 2024 in the private practice of the senior author, REDACTED. Prior to their inclusion in the study, patients were informed about the aims and written informed consent for their participation and use of their data was obtained.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In general, female patients with moderate to severe skin sagging of the face and neck, were eligible for this study. It was essential for participants to commit not to undergo any other facial treatments during the study period to ensure that the observed effects could be attributed solely to the treatment under investigation. Conversely, several exclusion criteria were applied to maintain the study's rigor and protect participant health: Individuals under the age of 18, pregnant or breastfeeding women, history of autoimmune diseases, intake of immunosuppressants or anti-inflammatory medications at the time of the study initiation, permanent facial implants, such as polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) or silicone, history of temporary or semi-permanent skin fillers in their face within the last 12 months. By establishing these strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study aimed to create a homogeneous participant group, thereby ensuring reliable and applicable results for the target population.

2.3. Product and Solution Specifications

Rennova Elleva® (Rennova, Goiânia, Brazil) is a sterile lyophilized preparation containing 210 mg of poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), 132 mg of carboxymethylcellulose, and 178 mg of pyrogen-free mannitol. It is designed for deep dermal, subcutaneous, or supraperiosteal injection.[

22]

To prepare the solution, 12 mL of sterile distilled water and 2 mL of lidocaine without a vasoconstrictor are added to the Rennova Elleva® vial. The vial is then placed in the Rennova Mixer 2.0 (Rennova, Goiânia, Brazil), a device used by healthcare professionals, and shaken horizontally at a speed of 2000 oscillations per minute for 1 minute to ensure thorough product homogenization.

From the prepared solution, a portion containing 90 mg of PLLA is utilized for treating the temple and neck regions. To achieve this, 6 mL of the prepared solution (which contains 90 mg of PLLA) is re-diluted to 18 mL, reducing the PLLA concentration to 5 mg/mL. Specifically, 15 mg of PLLA is used for each temple, 30 mg for the submental region, and 30 mg for the cervical region.

2.4. Procedure

The procedure began with cleansing the skin using a 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine solution. Following this, a 4% lidocaine-based anesthetic cream was applied to the treatment areas and left in place for 30 minutes to ensure adequate numbing, after which the cream was carefully removed. A 22G 50 mm cannula (Rennova, Goiânia, Brazil) was selected for the injections, with the entry point created using a 21G needle inserted at a 30-45 degree angle to the skin surface.

For the temple region treatment, the entry point was precisely positioned at the intersection of the middle and anterior thirds of the zygomatic arch. This strategic placement is crucial to avoid complications associated with the superficial temporal artery, which typically lies more laterally. For the neck region treatment, an entry point was made just below the chin for the submental area, and another entry point was centrally located at the level of the cricoid cartilage for treating the cervical region. The injection technique employed was linear retrograde injections without bolus administration, ensuring even distribution of the product along the treated areas. This approach follows the fanning technique, which is designed to cover a broader area more evenly. The targeted layer for product application was within the subcutaneous fat. All injections were carried out by the same experienced dermatologist to maintain consistency and precision in the procedure. Immediately after the injections, a vigorous massage using a 2% chlorhexidine degerming solution was performed to aid in the even distribution of the injected material. Patients were instructed to continue this massage regimen at home, performing the massage 5 times a day for 5 minutes each session over the next 5 days. This post-procedure care is vital for optimizing the results and ensuring the even dispersion of the product. To protect the entry points and prevent infection, a sterile occlusive dressing was applied to each site.

2.5. Clinical Evaluation

Clinical evaluations were conducted with each patient at six (monthly) intervals: Day (D)0, D30, D60, D90, D120, and D150. At each of these follow-up time points, a detailed anamnesis and a thorough physical examination was performed to monitor for possible adverse events. This included a close inspection of the treated areas to assess the condition of the skin, any changes in texture or appearance, and signs of inflammation or infection. Palpation of the facial skin was also conducted to check for any unusual lumps, tenderness, or other abnormalities that might indicate a complication. In addition, patients’ weights were measured using a regular digital scale on D0 and D150 to evaluate any potential gain during these data collection endpoints that could interfere with the clinical assessment. Height was reported by patients and this information was recorded on D0.

2.6. Ultrasound Evaluation

All ultrasound-based measurements were conducted by the same investigator (M.C.), a board-certified dermatologist and radiologist, to ensure consistency in the measurements and clinical assessments throughout the study. The ultrasound device utilized in this study was a Logiq e (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), a high-resolution equipment with high frequency linear probe, hockey stick–shaped (upper frequency range, 8–18 MHz), always applying its maximum frequency of 18 MHz. The ultrasound images were recorded in grayscale. Patients were seated at a 45°C upright position during the ultrasound imaging and measurement process. The transducer was positioned in a thick layer of contact gel (Aquasonic Clear Ultrasound Gel, Parker Laboratories Inc., Fairfield, NJ, USA) without direct skin contact to avoid compression of the facial soft tissues.

2.7. Patient Diary

Each patient received a diary to subjectively assess any adverse effects during the first 30 days post-procedure. They were instructed to document specific injection-related symptoms or signs, including "redness," "pain," "hardening," "swelling," "lumps," "bruising," and "skin discoloration." Additionally, patients were asked to rate the intensity of these symptoms as mild, moderate, or severe. These diaries were collected and analyzed during the D30 visit to evaluate the presence and severity of any adverse effects.

2.8. Subject Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (S-GAIS)

The Subject Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (S-GAIS)[

23] was used to evaluate patient satisfaction at two key points: D90 and D150. The GAIS is a five-point scale designed to measure the overall aesthetic improvement in a patient's appearance compared to their pre-treatment state. The scale ranges from exceptional improvement (1) and very improved (2), to improved (3), unaltered (4), and worsened (5) (

Table 1).

2.9. Physician Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale Assessment (P-GAIS)

In addition to the S-GAIS, the Physician Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (P-GAIS) was used to evaluate patient aesthetic improvement by two independent evaluators at both 90 and 150 days after injection. The P-GAIS system is scored analogue to the S-GAIS.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Differences between follow-up periods within the investigated groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To examine the relationships between the investigated parameters, bivariate correlation analysis was performed using Spearman's correlation coefficient (rs). All statistical calculations were conducted using SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A probability level of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for guiding conclusions. Results are presented as mean values with their respective standard deviations (mean ± SD), unless otherwise noted.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

In our study, a total of n=16 female patients of Hispanic ethnic background with an average age of 50.19 years (11.3) [range: 37-72 years] and an average BMI of 22.80 (2.2) [range: 18.4 – 26.2] at the start of the study were included.

3.2. Patient Diary

All patients included in this study completed the patient diary. Eight patients (50.0%) reported mild injection site reactions, and one patient (6.3%) reported a moderate site reaction. Redness at the injection site was reported in 5 patients (31.3%), with all cases being mild and transient in nature. The duration of mild injection site redness was 2.20 (1.6) days and was located in the temple and the neck in three and two patients, respectively. Pain at the injection site was reported in seven cases (43.8%), with all cases being mild. The average duration of mild injection site pain was 3.57 (2.4) days and was located in the neck in three patients, in the temple in two patients, and in both regions in two patients. Hardening at the injection site was reported in two cases (12.5%), with all cases being mild. The average duration of mild injection site hardening was 1.0 (0.0) day and was located in the neck in one patient and in the temple in one patient. Swelling at the injection site was reported in two cases (12.5%), with one case being mild and one case being moderate. The mild injection site reaction was located in the temple and lasted 1 day while the moderate reaction lasted 3 days without location specification. Mild lump formation at the injection site was reported in one case (6.3%) and was located in the neck with a duration of 1 day. Bruises at the injection site were reported in 3 cases (18.9%), with all cases being mild. The average duration of mild injection site bruising was 4.67 (4.6) days and was located in the neck in one patient, in the temple in one patient, and in both regions in one patient. Mild skin discoloration at the injection site was reported in 1 case and was located in the temple. All injection site reactions are summarized in

Table 2.

3.3. Subject Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale Assessment (S-GAIS)

At 90 days, the mean patient-assessed GAIS was 3.1 (SD: 0.86), indicating an overall perception of "improved" aesthetic appearance. By 150 days, the mean rating improved to 2.5 (SD: 0.97, p = 0.12), reflecting a "very improved" aesthetic outcome. Spearman's correlation analysis showed no significant association between weight change and S-GAIS scores at 90 days (ρ = 0.084, p = 0.80) or 150 days (ρ = -0.27, p = 0.40). Detailed results are presented in

Table 3.

3.4. Physician Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale Assessment (P-GAIS)

Blind evaluator 1 assessed GAIS scores at 90 days post-injection, yielding means of 3.3 (SD: 0.90) for the temple and 3.1 (SD: 0.94) for the neck. At 150 days, scores were 2.7 (SD: 0.82, p = 0.16) for the temple and 2.5 (SD: 1.2, p = 0.035) for the neck. Similarly, blind evaluator 2 reported mean scores of 3.1 (SD: 0.54) for the temple and 2.5 (SD: 0.82) for the neck at 90 days, with further improvements at 150 days to 2.3 (SD: 0.82, p = 0.005) for the temple and 2.0 (SD: 0.94, p = 0.014) for the neck.

Spearman's correlation analysis revealed no statistically significant relationship between weight change and P-GAIS scores for either evaluator. Correlations of scores by blind evaluator 1 and weight change revealed weak correlations at 90 days after injection in both temple (ρ = 0.016, p = 0.96) and neck (ρ = -0.041, p = 0.91) regions, as well as at 150 days after injection in both temple (ρ = 0.044, p = 0.90) and neck (ρ = 0.36, p = 0.31) regions. Correlations of scores by blind evaluator 2 and weight change revealed positive trends at 90 days after injection in both temple (ρ = 0.30, p = 0.37) and neck (ρ = 0.041, p = 0.91) regions, as well as at 150 days after injection in both temple (ρ = 0.30, p = 0.35) and neck (ρ = 0.15, p = 0.69) regions. Although not statistically significant, weight increase was associated with poorer P-GAIS evaluation.

Interrater reliability of the P-GAIS scores was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation. For the measurements 90 days after injection, a moderate positive correlation was observed in the temple region (ρ = 0.41,

p = 0.21) and a moderate-to-strong correlation in the neck region (ρ = 0.53,

p = 0.094), although neither correlation reached statistical significance. In contrast, measurements 150 after injection demonstrated negligible agreement in the Temple region (ρ = -0.093,

p = 0.79) and a weak-to-moderate correlation in the Neck region (ρ = 0.33,

p = 0.35). These findings indicate limited and inconsistent interrater reliability across timepoints and anatomical regions. Detailed results are summarized in

Table 3.

3.5. Clinical Evaluation

In the clinical evaluations, no major adverse events were reported.

3.6. Ultrasound Examination

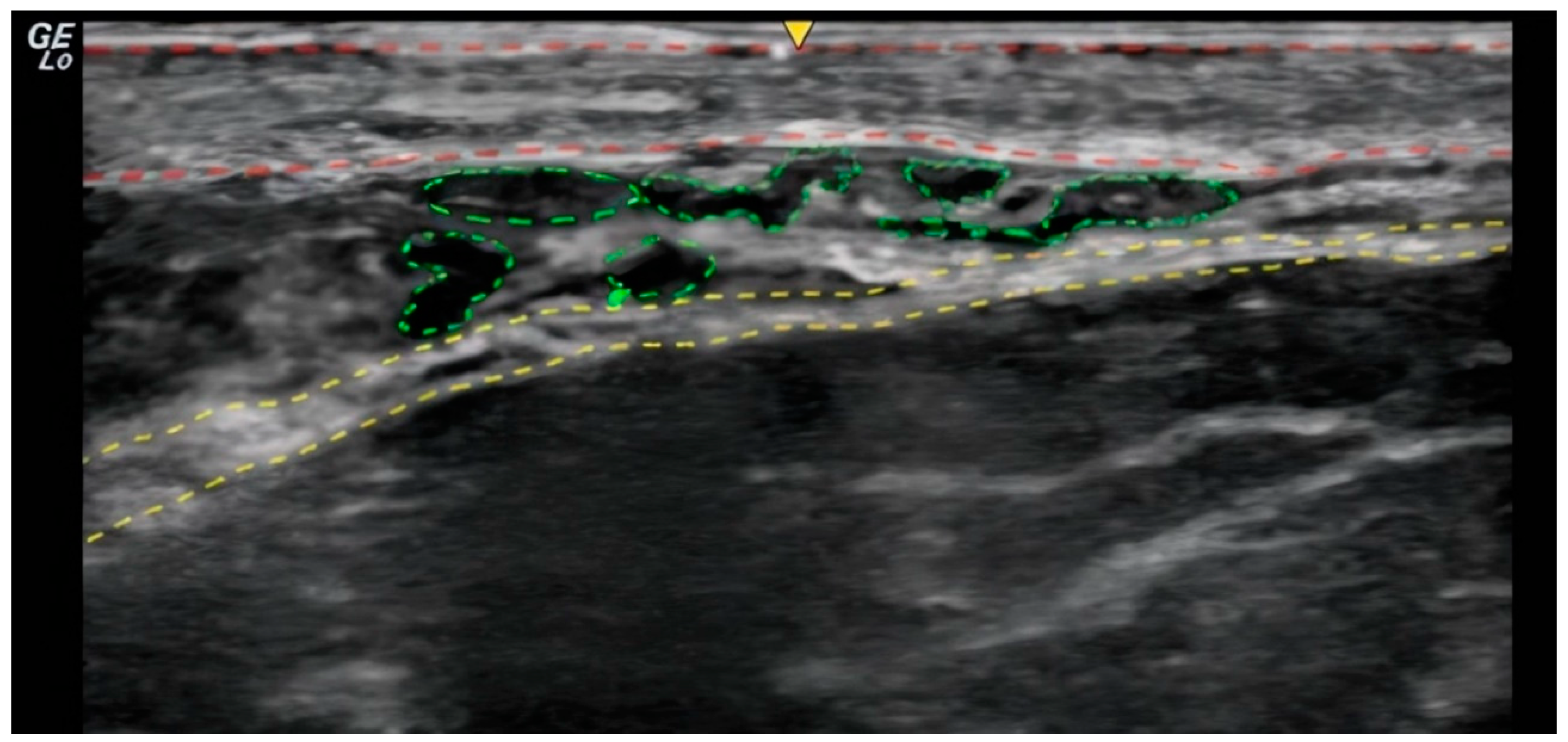

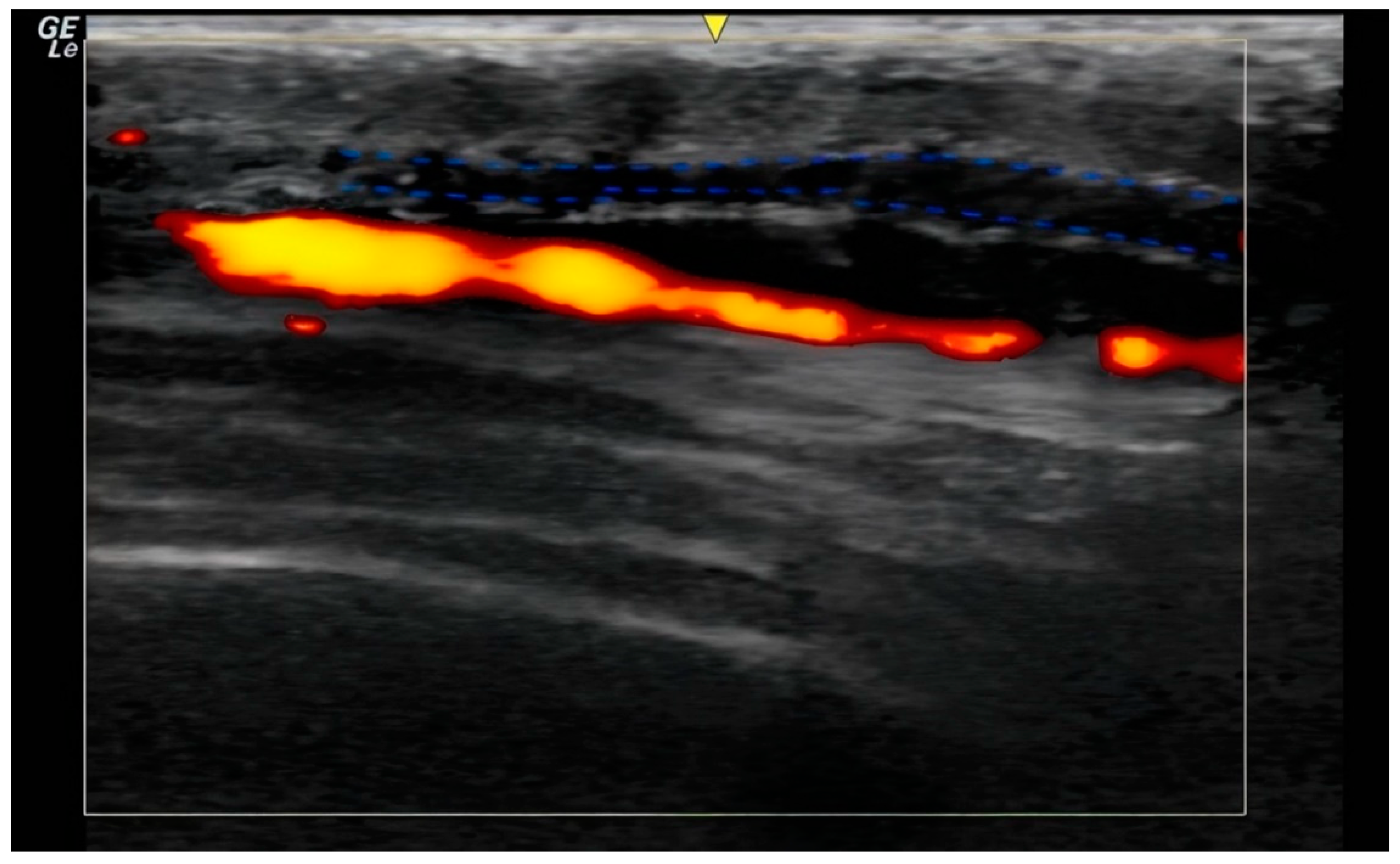

In the ultrasound examination, the correct placement of the product was confirmed in all cases and no irregularities regarding the injection site anatomy were found. (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Although often overlooked by patients as contributing factors to overall facial aesthetics, experienced aesthetic practitioners typically incorporate treatments of the neck and temples in a holistic approach to full-face rejuvenation.[

24] However, there is a scarcity of clinical studies investigating the efficacy and safety of soft tissue fillers in these regions. To address this knowledge gap, we herein introduced and evaluated an injection technique using hyperdiluted Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA). Our approach aimed to address the unique anatomical challenges of the temple and neck areas, such as varying thickness of the skin and the underlying soft tissues.[

25,

26] By tailoring the concentration of PLLA to these anatomical characteristics, we hypothesized that our technique would not only warrant high safety but also sustained patient satisfaction. Notably, when evaluating the outcomes, the authors primarily relied on the patient’s perception and assessment, for both efficacy (i.e., S-GAIS) and safety profile (i.e., patient diary), thereby moving away from the often-biased injector-centered perspective and returning to the core of aesthetic medicine: the patient's experience.

Patient satisfaction was assessed by patients using the 5-point S-GAIS from 1 (“exceptional improvement”) to 5 (“worsened”) (

Table 1). The average rating was 3.1 at 90 days, equating to an “improved” aesthetic appearance. Interestingly, the clinical results not only remained stable but also improved over a longer follow-up period, with an average rating of 2.5 at 150 days, thereby approaching a “very improved” rating defined as “2” by S-GAIS. Put differently, 81.5% (13) of patients reported at least an “improved” (i.e., ≥ 3) aesthetic appearance at 90 days, which yet again increased to 87.5% (14) at 150 days. A similar trend can be observed in the P-GAIS, where scoring by both evaluators showed improvements at 150 days compared to 90 days after injection. Moreover, no significant correlation could be established between weight gain over the study period and changes in S- and P-GAIS. A recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials involving patients treated with tissue fillers for the nasolabial fold area revealed that pooled patient satisfaction was highest during the initial follow-up examination and then progressively decreased.[

27] On the contrary, our finding of gradually increasing patient satisfaction highlights both the longevity and the beneficial aesthetic effects of the hyperdiluted PLLA injections over time. This may be mainly attributed to the collagen-inducing capacities of PLLA, which promotes tissue remodeling and stepwise improvements in skin quality. As PLLA microparticles are gradually resorbed by the body, they stimulate fibroblasts to produce new collagen, increasing skin thickness and firmness.[

5,

11,

12] This process continues over several months, echoing in higher patient satisfaction at the 150-day mark.[

28] To capitalize on these effects, precise product placement in the desired layer and the employed injection technique is essential: Ultrasound-guided subcutaneous placement using a retrograde fanning injection technique ensures optimal contact between the product and the dermis, thereby stimulating collagen synthesis in dermal fibroblasts (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).[

29]

From a safety standpoint, no major adverse events were recorded through a clinical expert lens. Injection site reactions, mostly mild, were reported by half of the patients. The most common reactions included pain (seven patients) and redness (five patients) at the injection site. Less commonly reported reactions included bruising (three patients), swelling (two patients), hardening (two patients), lump formation (one patient), and skin discoloration (one patient) (

Table 2). It is worth noting that this, at first glance, relatively high rate of these minor adverse effects is likely due to the methodology of the study, whereby patients were vigilant and meticulously recorded any change in their condition. Monitoring and documenting symptoms via a patient diary increases the likelihood of capturing even the slightest variations in health status that might otherwise go unnoticed by clinical experts.[

30] Studies relying on the latter would typically only report adverse events when they are exceptional or outside the norm of daily observations. This “complication rate”, therefore, rather reflects comprehensive patient-centered data collection rather than a high incidence of clinically significant issues. Importantly, with the exception of one moderate injection site swelling, all reactions were mild and transient. The injection site reactions appear to be consistent with those reported in previous studies on PLLA and other injectable treatments, suggesting that they are more related to the injection procedure itself rather than the product used.[

31,

32,

33] The use of ultrasound examinations in our study further confirmed the absence of adverse events such as injury of neurovascular structures, providing additional reassurance regarding the safety of our technique.

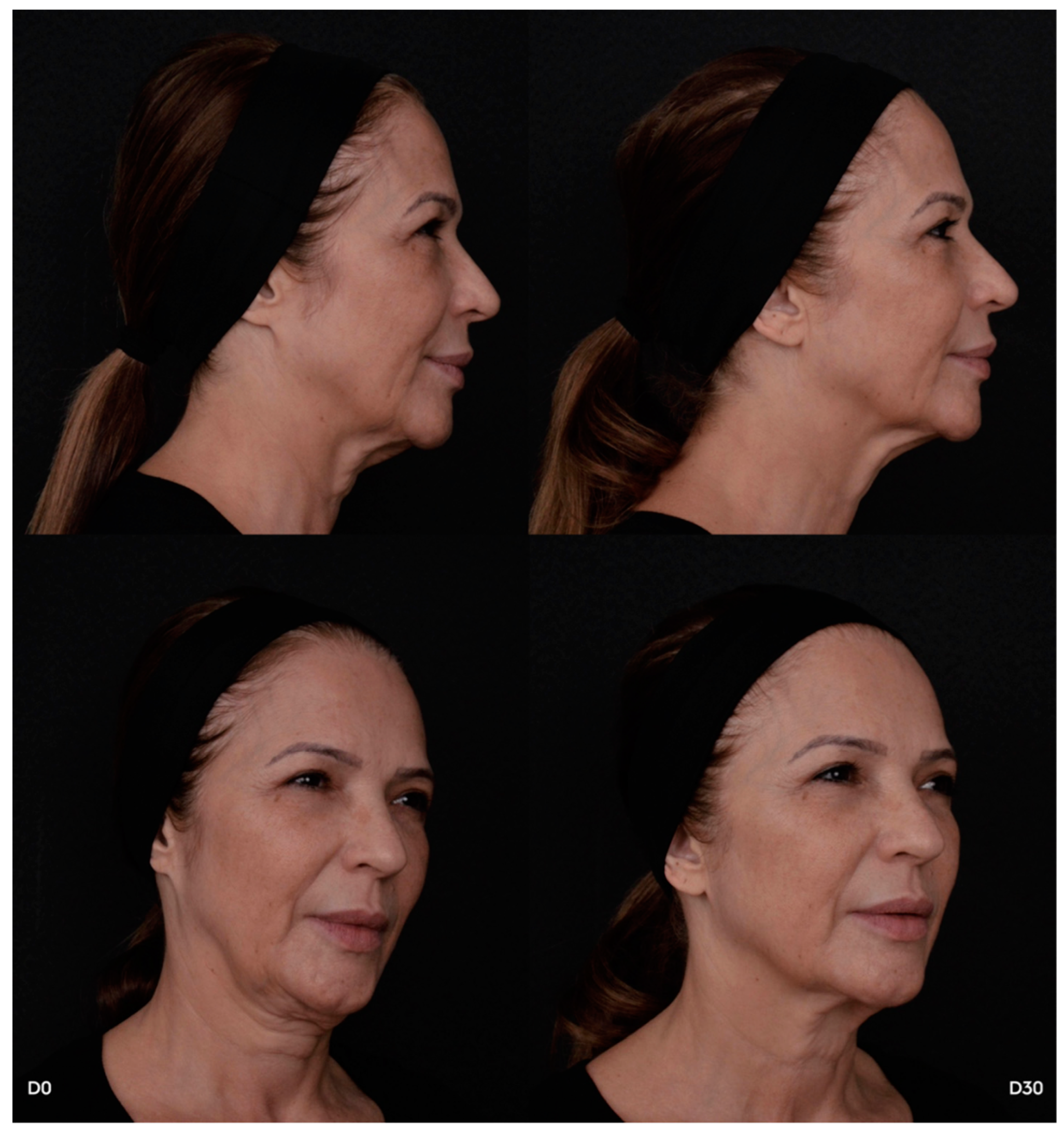

In summary, treating the temple and neck area with hyper-diluted PLLA is a safe and effective option for facial rejuvenation, yielding high levels of patient satisfaction and low rates of clinical adverse effects. Even if patients may report minor symptoms after treatment, these are usually short-lived and do not compromise the overall positive result. The anatomically aligned approach ensures even distribution of PLLA according to the structural characteristics of different skin regions, minimizing complications and maximizing aesthetic outcomes (

Figure 3). The stability and gradual increase of S-GAIS ratings over time emphasize the long-lasting efficacy of PLLA-based soft tissue filler injections.

For patients, understanding the safety and efficacy of customized PLLA injections in anatomically challenging areas such as the temples and neck can provide reassurance and inform their choices about aesthetic treatments. For providers, our study offers practical insights into how adjusting PLLA concentrations to suit the anatomical and structural nuances of each target area can enhance treatment outcomes and reduce the risk of complications. In fact, on broader scale, the implications of our findings extend beyond the specific areas treated in this study. The concept of tailoring collagen biostimulator concentrations to the anatomical characteristics of different skin regions can also be applied to other areas. This personalized approach to aesthetic medicine underscores the importance of considering individual anatomical differences when designing treatment protocols.

5. Limitations

The study's findings should be interpreted considering its inherent limitations. First, the data collection relied heavily on subjective self-reporting by participants, which may have led to some adverse events being either overreported or unrecognized. Second, the study sample was limited in size and drawn exclusively from the private healthcare sector, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results to the broader population. Third, the study included only female participants, which means that the results presented herein need to be validated in male patients, who typically have different skin characteristics that could affect treatment outcomes.[

34] Fourth, the follow-up period of 150 days does not account for all long-term effects and satisfaction, which are, however, crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the treatment's ultimate efficacy and safety. Lastly, the exclusion of individuals with certain medical conditions and those using specific medications may have created a more homogeneous sample, but it also limits the applicability of the findings to a wider, more diverse patient population.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that injections of hyper-diluted Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA) are safe and effective treatments for facial rejuvenation of the temple and neck areas, offering sustained patient satisfaction and minimal adverse effects. The gradual improvement in patient satisfaction, as reflected by increasing S-GAIS ratings, underscores the long-term benefits of this approach, likely due to the collagen-stimulating properties of PLLA. Importantly, the tailored injection technique, which accounts for the unique anatomical characteristics of these regions, minimizes adverse effects while maximizing results. This study not only provides valuable insights for practitioners but also reinforces the importance of customized treatment strategies in aesthetic medicine. Future research should continue to explore the anatomically adjusted injection of collagen biostimulator in other challenging areas to further refine and expand this promising approach.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.F.B, C.S., and T.C.N.J.; Methodology, B.S.F.B, and T.C.N.J; Statistical Analysis, B.S.F.B., C.S., and T.C.N.J; Writing – original draft, B.S.F.B. and T.C.N.J; Writing – review and editing, C.S., C.M.O.L.d.N., L.G.B., M.C.Z., and G.L.T.A.; Supervision, B.S.F.B. and T.C.N.J.

Funding

The authors received financial support from Rennova® for the research and publication of this article. The products utilized in this study were donated by the injectors for the purposes of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Bruna S. F. Bravo is a medical consultant and speaker for Rennova®, Allergan Aesthetics, Merz Aesthetics®, and L'Oréal. Thamires Cavalcante, Maria C. Zafra, and Mariana Calomeni are medical speakers for Rennova®.

References

- Attenello, N.H.; Maas, C.S. Injectable fillers: review of material and properties. Facial Plast Surg FPS. 2015;31(1):29-34. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Van Abel, D. Neocollagenesis in human tissue injected with a polycaprolactone-based dermal filler. J Cosmet Laser Ther Off Publ Eur Soc Laser Dermatol. 2015;17(2):99-101. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.; Guana, A.; Volk, A.; Daro-Kaftan, E. Single-arm study for the characterization of human tissue response to injectable poly-L-lactic acid. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2013;39(6):915-922. [CrossRef]

- Plastic Surgery Statistics. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Accessed July 6, 2024. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics.

- Fitzgerald, R.; Bass, L.M.; Goldberg, D.J.; Graivier, M.H.; Lorenc, Z.P. Physiochemical Characteristics of Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA). Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(suppl_1):S13-S17. [CrossRef]

- Vleggaar, D. Facial volumetric correction with injectable poly-L-lactic acid. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1511-1517; discussion 1517-1518. [CrossRef]

- Gogolewski, S.; Jovanovic, M.; Perren, S.M.; Dillon, J.G.; Hughes, M.K. Tissue response and in vivo degradation of selected polyhydroxyacids: polylactides (PLA), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHB/VA). J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(9):1135-1148. [CrossRef]

- Lemperle, G.; Morhenn, V.; Charrier, U. Human histology and persistence of various injectable filler substances for soft tissue augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27(5):354-366; discussion 367. [CrossRef]

- Stein, P.; Vitavska, O.; Kind, P.; Hoppe, W.; Wieczorek, H.; Schürer, N.Y. The biological basis for poly-L-lactic acid-induced augmentation. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78(1):26-33. [CrossRef]

- Hanke, C.W.; Redbord, K.P. Safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid in HIV lipoatrophy and lipoatrophy of aging. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2007;6(2):123-128.

- Ratner, B.D.; Bryant, S.J. Biomaterials: where we have been and where we are going. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:41-75. [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, K.; Dorizas, A.; Lorenc, P.; Sadick, N.S. Randomized, Controlled, Multicentered, Double-Blind Investigation of Injectable Poly-L-Lactic Acid for Improving Skin Quality. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2019;45(5):718-724. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H.; Alhajj, M.; Fakoya, A.O.; Sharma, S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed August 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/.

- Christen, M.O. Collagen Stimulators in Body Applications: A Review Focused on Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA). Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:997-1019. [CrossRef]

- Vanaman, M.; Fabi, S.G. Décolletage: Regional Approaches with Injectable Fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):276S-281S. [CrossRef]

- Zac, R.I.; Da Costa, A. Poly-L-Lactic Acid for the Neck. In: Costa AD, ed. Minimally Invasive Aesthetic Procedures : A Guide for Dermatologists and Plastic Surgeons. Springer International Publishing; 2020:529-532. [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, R.; Hexsel, D. Poly-L-lactic acid for neck and chest rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2009;35(8):1228-1237. [CrossRef]

- Vleggaar, D. Poly-L-lactic acid: consultation on the injection techniques. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2006;20 Suppl 1:17-21. [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, T.G.; Kachare, M.D. The Utilization of Poly-l-Lactic Acid as a Safe and Reliable Method for Volume Maintenance After Facelift Surgery With Fat Grafting. Aesthetic Surg J Open Forum. 2022;4:ojac014. [CrossRef]

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2014;13(4 Suppl):s44-51.

- Palm, M.D.; Woodhall, K.E.; Butterwick, K.J.; Goldman, M.P. Cosmetic use of poly-l-lactic acid: a retrospective study of 130 patients. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2010;36(2):161-170. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.L.; Teodoro MRF de, M. Protocol for the Use of Poly-L-Lactic Acid (Elleva and Elleva X) for Skin Flaccidity in Body Areas. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2023;14(2):1-9.

- Narins, R.S.; Brandt, F.; Leyden, J.; Lorenc, Z.P.; Rubin, M.; Smith, S. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2003;29(6):588-595. [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, A.; Forte, R. Cosmetic use of polylactic acid: report of 568 patients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(4):239-248. [CrossRef]

- Ingallina F, Alfertshofer MG, Schelke L, et al. The Fascias of the Forehead and Temple Aligned-An Anatomic Narrative Review. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2022;30(2):215-224. [CrossRef]

- Minelli, L.; van der Lei, B.; Mendelson, B.C. The Deep Fascia of the Head and Neck Revisited: Relationship with the Facial Nerve and Implications for Rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;153(6):1273-1288. [CrossRef]

- Stefura T, Kacprzyk A, Droś J, et al. Tissue Fillers for the Nasolabial Fold Area: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45(5):2300-2316. [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Adelnia, H.; Ta, H.T. Collagen and the effect of poly-L-lactic acid based materials on its synthesis. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(17):5714-5731. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Dong, C. Poly-L-Lactic acid increases collagen gene expression and synthesis in cultured dermal fibroblast (Hs68) through the TGF-β/Smad pathway. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(4):1213-1219. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Stone, A.A. Ambulatory and diary methods can facilitate the measurement of Patient Reported Outcomes. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2016;25(3):497-506. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, B.S.F.; Carvalho R de, M. Safety in immediate reconstitution of poly-l-lactic acid for facial biostimulation treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(5):1435-1438. [CrossRef]

- Sapra, S.; Stewart, J.A.; Mraud, K.; Schupp, R. A Canadian study of the use of poly-L-lactic acid dermal implant for the treatment of hill and valley acne scarring. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2015;41(5):587-594. [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, H.S. The safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid on sunken cheeks in Asians. J Cosmet Laser Ther Off Publ Eur Soc Laser Dermatol. 2014;16(4):180-184. [CrossRef]

- Rahrovan, S.; Fanian, F.; Mehryan, P.; Humbert, P.; Firooz, A. Male versus female skin: What dermatologists and cosmeticians should know. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(3):122-130. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).