I. Introduction

The global irnnsition towards renewable energy sources (RES) has spurred the advancement of photovoltaic (PV) panels. Notably, the production costs of electricity generated from PV panels have markedly decreased,

\vhile simultaneously achieving higher energy conversion efficiencies. Specifically, the levelized cost of electricity for large-scale PV panels witnessed a 73% reduction between 2010 and 2017. This combination of reduced costs and enhanced efficiency has positioned PV panels as a competitive alternative for RES adoption in numerous countries.However, due to the reliance of PV panel energy output on varying weather conditions such as cloud cover and solar irradiance, the stability of energy production remains uncertain. Consequently, comprehending and managing this output variability is of paramount interest to various stakeholders in the energy market. Transmission system operators aim to balance the grid by accurately predicting PV panel energy output, as generating excess or insufficient electricity often results in penalty fees. On89 the other end of the spectrum, electricity traders focus on longer timeframes, primarily day-ahead forecasts, since most electricity trading occurs in the day-ahead market. Hence, the profitability of these endeavors hinges on the capability to precisely forecast the fluctuating energy output from solar PV panels. As more countries opt to invest in RES, the utilization of solar PV panels is anticipated to continue its upvv’ard trajectory. Consequently, the demand for effective methods to forecast PV energy output is poised to increase. Despite the clear demand for accurate and efficient PV pane] energy frirecasts, the solution remains intricate. The current research within this domain grapples with numerous complexities. One prominent challenge is the inherent variability in weather conditions, vd1ich poses difficulties for precise weather forecasting.

Concurrently with the growing need for PV power forecasting solutions, the adoption of machine learning (ML) techniques has gained traction in recent years, surpassing traditional time series predictive models. Although ML techniques are not novel, the improvement in computational capabilities and the greater availability ofhigh quality data have rendered these techniques highly effective frir forecasting. This prompts an intriguing avenue of investigation in the realm of solar power output prediction using machine learning techniques and ensemble techniques.

II. Feature Enginnerin in Solar Forecasting

Feature engineering plays a crucial role in improving the accuracy and reliability of solar forecasting models. Solar forecasting aims to predict the amount of solar energy that will be generated by photovoltaic (PV) systems based on various factors. Here are some important features and techniques used in feature engineering for solar forecasting:

Relative Humidity:Relative humidity holds significance in solar forecasting due to its impact on solar panel efficiency and solar radiation. Including relative humidity data in forecasting models enhances the accuracy of calculating available solar irradiance, estimating cloud cover effects on solar radiation, considering pollution and dust effects on panel performance, and predicting efficiency reductions due to moisture accumulation. Incorporating relative humidity in solar forecasting aids in optimizing solar energy generation and informs operational decisions effectively.

Temperature:Temperature plays a crucial role in solar forecasting as it affects solar panel performance and efficiency. Elevated temperatures can lead to reduced panel efficiency due to altered electrical conductivity. Integrating temperature data into solar forecasting models helps gauge potential effects on solar energy production, leading to improved optimization and planning of solar power systems.

Wind Speed: Wind speed does not directly correlate with solar forecasting. While solar forecasting centers on estimating solar irradiance based on cloud cover, atmospheric conditions, and panel efficiency, wind speed pertains to wind power forecasting for predicting electricity generation from wind turbines. Although wind speed might indirectly influence solar forecasting under certain circumstances (e.g., cloud movement or dust dispersion effects), it remains a non-core variable in solar forecasting models.

Cloud Cover:Cloud cover holds pivotal importance in solar forecasting models, ensuring accurate predictions of solar energy production. Clouds obstruct sunlight and significantly diminish solar irradiance at the Earth’s surface. Integration of cloud cover data into forecasting models aids operators in estimating reductions in solar irradiance, facilitating adjustments to energy generation strategies. This fosters precise solar energy forecasts, enabling adept planning and management of solar power systems.

Angle of Incidence:The angle of incidence governs how sunlight strikes solar panels, impacting energy capture and efficiency. Factoring the angle of incidence into solar forecasting models results in more precise estimates of solar energy generation. This approach optimizes solar panel positioning and tilt for maximum efficiency.

ZenithAngle:The zenith angle is vital in solar forecasting, representing the angle between the sun and a vertical line from the observer to the sun. It influences solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface and significantly influences energy production. Incorporating the zenith angle in forecasting models allows accurate estimation of available solar irradiance, thereby enhancing energy generation strategies.

AzimuthAngle:The azimuth angle holds importance in solar forecasting, referring to the sun’s horizontal direction relative to an observer or solar panel. It helps determine the sun’s position in the sky, crucial for estimating solar energy generation. By considering the azimuth angle, forecasting models predict solar irradiance and optimize panel positioning and orientation to maximize energy production.

III. Machine Learning Models

J\fachine learning stands as a pivotal segment within the realm of artificial intelligence and computer science. Its core focus revolves around harnessing data and algorithms to enmlate the learning process of humans, progressively boning its precision over time. Embedded,vithin the burgeoning field of data science. machine learning employs statistical techniques to train algorithms for the purpose of making classifications or predictions.

These algorithms vvield the pm,ver to address an array of business challenges, spanning Regression, Classification, Forecasting, Clustering, and Associations, among others. Specifically, Regression analysis constitutes a statistical approach geared towards modeling tbe interplay between dependent (target) and independent (predictor) variables, often encompassing multiple independent variables. This method oiters insight into how the dependent variabks value evolves in relation to an independent variable, w-hile other predictors remain constant. Its prowess lies in predicting continuous real~world values, encompassing aspects sucb as temperature, age, salary, and price.

Regression analysis serves as an indispensable tool that unveils correlations between variables and facilitates the anticipation of continuous output variables, predicated on one or more predictor variables. Its primary utilities encompass prediction, forecasting, time series modeling, and discerning causal-effect linkages between variables.

A. Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression serves as a valuable tool for gauging the intricate connections between two or more independent variables and a sole dependent variable. This method finds its utility in scenarios vdiere a comprehensive understanding is sought, such as evaluating the impact of factors like rainfall, temperature, and fortilizer quantity on crop growth.

This approach caters to two primary inquiries:

The strength of the relationship among multiple independent variables and a single dependent variable, exemplified by the interplay of rainfall, temperature, and fertilizer quantity on crop grmvth.

The projected value of the dependent variable given specific values of the independent variables. For instance, it can predict crop yield based on distinct levels of rainfall, temperature, and fertilizer application.

The mathematical foundation of multiple linear regression is encapsulated by the foHmving formula:

\Vhere:

- -

y stands for the predicted value of the dependent variable.

- -

f3o signifies they-intercept, representing the value ofy when aU other factors are zero.

- -

B, to Bk represent the regression coefficients associated vvith each independent variable (xi to Xk).

- -

i.:: denotes the model error, porirnying the degree of variation in our estimations.

In the quest to determine the optima] line of fit for each independent variable, multiple linear regresston involves three crucial computations:

Deriving regression coefficients that minimize the overall model error.

Calculating the t statistic of the overarching model.

Assessing the corresponding p value, which gauges the likelihood of the t statistic arising due to chance, assuming tbe null hypothesis that no relationship exists between the independent and dependent variables.

This pmcess extends to the calculation of the t statistic and p value for every regression coefficient integrated into the model.

B. Ridge Regression

In the realm of ordinaiy multiple linear regression, a set of p predictor variables collaborates with a response variable to formulate a model in the structure of:

Y =Bo-:- fhX1 + r)2X2 + ··” + BpXp + £

Unpacking the terminology:

- -

Y denotes the response variable.

- -

XJ stands for the jth predictor variable.

- -

p j represents the average influence on Y when a one-unit increase is observed in XJ, \vhile keeping other predictors constant”

- -

i.:: represents the eITor term.

To compute the values of po, Bi, f.:b, .. _, BP, the least squares method comes into play, aiming to rninirnize the summation of squared residuals (RSS):

Breaking down the fbrmula:

- -

:E signifies the sunm1ation operation.

- -

Yi represents the actual response value for the ith observation.

- -

Yi symbolizes the predicted response value generated by the multiple linear regression model.

However, the situation becomes intricate when predictor variables showcase significant correlation, vvhich leads to the emergence of multicollinearity. This phenomenon can render the coefficient estimates of the model unstable, introducing a high degree of variability.

To address this challenge without entirely discarding particular predictor variables, an alternative technique known as ridge regression comes into play. Ridge regression embarks on the task of minimizing the ensuing expresswn:

Here:

- -

j ranges from 1 to p.

- -

I, (lambda) assumes a non-negative value.

The supplementary term vvithin the equation is tenned a “shrinkage penalty.’’ When ;, equals 0, this penalty component holds no sway, causing ridge regression to yield coefficient estimates akin to those of the least squares approach. However, as ’A, ascends towards infinity, the influence of the shrinkage penalty gains prominence, compelling the coefficient estimates of ridge regression to gradually approach zero.

Tn practical application, predictor variables bearing lesser influence on the model tend to converge towards zero at an accelerated rate due to the intrinsic shrinkage impact.

C. Lasso Regression

ln the context of ordinary multiple linear regression, a collection of p predictor variables and a response variable combine to constrnct a model characterized by the equation:

Y = Bo+ B1X1 + B,X2 + ... + BpXp + S

The key elements in this equation are:

- -

Y: Represents the response variable.

- -

XJ: Denotes the jth predictor variable.

- -

f3j: Signifies the average impact on Y resulting from a one-unit increase in Xj, keeping aU other predictors constant.

- -

s: Stands for the error term.

The values of Po, f31, Pz, “ .., f\1 are determined through the utilization of the least squares method, which aims to minimize the sum of squared residuals (RSS):

RSS = I{yi - 5\)2

In this equation:

- -

I: represents the summation symbol.

- -

Yi signifies the actual response value for the ith observation.

- -

Yi stands fiff the predicted response value derived from the multiple linear regression model.

However, situations arise where predictor variables exhibit strnng correlation, leading to the emergence of multicollinearity. This phenmnenon can result in unreliable coefficient estirnates for the model, with an increased potential for high variance. In essence, when the model is applied to new, previously unseen data, its performance is likely to be suhpar.

One approach to address this challenge is by employing lasso regression, which endeavors to minimize the foUowing expression:

Here:

- -

j ranges from 1 to p.

- -

I, (lambda) assumes a non-negative value.

The additional term within the equation is referred to as a “shrinkage penalty.’° vVhen ;.., equals 0, this penalty term holds no impact, rendering lasso regression equivalent to the coefficient estimates obtained through the least squares method.

However, as ““ progressively increases towards infinity, the influence of the shrinkage penalty intensifies. Consequently, predictor variables deemed less significant in the model experience a substantial shrinkage effect, moving them towards zero. In certain cases, some predictor variables might even be eliminated from the _model entirely.

D. Decision Tree Regression

The term “decision tree” aptly reflects its operational principle based on conditions. This method boasts efficiency and employs robust algorithms for predictive analysis. It comprises fundamental components: internal nodes, branches, and terminal nodes. In the context of a decision tree, each internal node conducts a “test” on an attribute, with branches indicating the outcomes of these tests, while every leaf node signifies a class label. Its versatility is evident as it caters to both classification and regression tasks, constituting two essential types of supervised learning algorithms. However, the sensitivity of decision trees to their training data is noteworthy - even minor alterations in the training set can lead to significant variations in the resulting tree structures.

Certainly, let’s delve into the intuition and mathematical theory behind Decision Tree Regression (DTR). Intuition:

Think of a decision tree as a series of questions that help you arrive at a decision. In the context of regression, the goal is to predict a continuous output value for a given set of input features. Each internal node of the tree poses a question based on a specific feature, and depending on the answer, you move to one of the child nodes. The leaf nodes provide the predicted output values.

Mathematical Theory:

At each internal node, the algorithm chooses the feature and threshold that best splits the data into subsets. The splitting is determined by a criterion that aims to minimize the variance (or another suitable measure) of the target values within each subset. In the case of regression, a common splitting criterion is to minimize the mean squared error (MSE), which can be defined as follows for a given node N:

[ MSE(N) = \frac{l}{INI} \sum_{i \in N} (y_i- \bar{y}_N)l’2]

Here, \( y_i \) represents the target value of the i-th data point in node N, and \( \bar{y}_N \) is the mean of the target values in node N.

2. [“l/i>fff..: r· rfli {:,3

When a leaf node is created, it’s assigned a constant value that represents the prediction for all data points falling into that leaf For regression, this value is typically the average (or median) of the target values within the leaf

The process of building a decision tree is recursive. Starting from the root node, the algorithm selects the best feature and threshold for splitting the data. Then, it moves to the child nodes and repeats the process until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., maximum tree depth, minimum number of samples per leaf).

Decision trees have a tendency to overfit the training data if they become too deep. Overfitting refers to the model capturing noise in the data instead of the underlying patterns. Pruning is a technique to address this by removing or collapsing nodes that do not contribute significantly to the model’s performance on validation data.

E. Support Vector Regression

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is built on the principles of Support Vector Machines (SVM) with some nuanced distinctions. Rather than finding a linear or non-linear decision boundary, as in classification SVM, SVR aims to establish a curve that captures relationships between data points for regression tasks. Unlike using the curve as a decision boundary, SVR employs the curve to determine how well the curve aligns with the position of data points. Support Vectors, crucial to SVR, aid in identifying the closest match between the curve and data points.

Here is a summarized rendition of the SVR process:

- 3.

-

Data Collection:

Gathering a training set composed of samples that serve as the basis for prediction. It’s important that the features in the training set appropriately cover the domain of interest since SVR interpolates only within this domain.

- 4.

-

Kernel Selection:

Choosing a suitable kernel, such as Sigmoid, Polynomial, Gaussian, etc., based on the problem’s nature. Kernels have hyperparameters that require tuning. Here, the Gaussian Kernel is taken as an example.

- 5.

-

Creation of Correlation Matrix:

Constructing a correlation matrix by evaluating pairs of data points from the training set. Regularization is introduced on the diagonal. This yields a semidefinite matrix representing correlations in a higher-dimensional space than the original training data.

- 6.

-

Solving for Estimator:

Solving for the coefficients a in the equation:

Where

y=Ka,

y represents vector values corresponding to the training set,

K is the correlation matrix, and

a is the set of coefficients to be determined. Efficient methods like QR/Cholesky can be used to invert the correlation matrix.

- 7.

-

Forming the Estimator:

Once a is known, the estimator can be formulated using the coefficients and the chosen kernel. For test points, the estimator calculates y* using a and the kernel function. The result of this estimation is

IV. Ensemble Learning Models

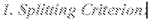

A. Random Forest

Random forest, as its name suggests, comprises an enormous amount of individual decision trees that work as a group or as they say, an ensemble. Every individual decision tree in the random forest lets out a class prediction and the class with the most votes is considered as the model’s prediction.

Random forest uses this by permitting every individual tree to randomly sample from the dataset with replacement, bringing about various trees. This is known as bagging.Random Forest has multiple decision trees as base learning models. We randomly perform row sampling and feature sampling from the dataset forming sample datasets for every model. This part is called Bootstrap.

Assumptions.for Random Forest

Since the random forest combines multiple trees to predict the class of the dataset, it is possible that some decision trees may predict the correct output, while others may not. But together, all the trees predict the correct output. Therefore, below are two assumptions for a better Random forest classifier:

There should be some actual values in the feature variable of the dataset so that the classifier can predict accurate results rather than a guessed result.

The predictions from each tree must have very low correlations.

Why use Random Forest?

Below are some points that explain why we should use the Random Forest algorithm:

It takes less training time as compared to other algorithms.

It predicts output with high accuracy, even for the large dataset

It runs efficiently.It can also maintain accuracy when a large proportion of data is missing.

How does Random Forest algorithm work?

Random Forest works in two-phase first is to create the random forest by combining N decision tree, and second is to make predictions for each tree created in the first phase.

The Working process can be explained in the below steps and diagram:

Step-1: Select random K data points from the training set.

Step-2: Build the decision trees associated with the selected data points (Subsets).

Step-3: Choose the number N for decision trees that you want to build.

Step-4: Repeat Step I & 2.

Step-5: For new data points, find the predictions of each decision tree, and assign the new data points to the category that wins the majority votes.

Figure 1.

Random Forest Regression Model.

Figure 1.

Random Forest Regression Model.

B. Bagging Regressor

The Bagging Regressor serves as an ensemble meta-estimator, functioning by training base regressors on randomly chosen subsets of the original dataset. These individual models’ predictions are then combined, either by averaging or voting, to generate the final prediction. This technique effectively mitigates the variance of a primary estimator (like a decision tree) by infusing randomness during its construction process and subsequently forming an ensemble. Referred to as the “bagged regressor” or “bootstrap aggregating regressor,” this ensemble learning algorithm enhances prediction accuracy in regression tasks. It’s an adaptation of the bagging concept, tailored for regression scenarios. The fundamental concept involves training several regression models on distinct subsets of training data, enabling them to capture various patterns and minimize the influence of outliers. This process results in a robust ensemble that contributes to more accurate predictions.

C. ADA Boost Regressor

Adaboost, short for “Adaptive Boosting,” was one of the earliest boosting techniques that gained widespread popularity. Introduced by Freund and Schapire in 1997, it involves adjusting sample weights dynamically during training rather than relying on a fixed learning rate. This dynamic approach, which adapts the weights, is why it’s termed “adaptive.” It leads to the creation of a boosting regressor that consistently outperforms a simple base estimator. Adaboost combines multiple basic learning models (called “Weak Learners”) to construct a powerful regressor.

To develop the Adaboost.R2 algorithm, we start by defining the weak learner, loss function, and the available dataset. N represents the total samples, and the ensemble comprises M weak learners, indexed as n=l..N and m=l..M.

Equations (1), (2), and (3) define the data, weak learner model, and loss function, respectively. Here, xn represents rows in matrix X with d features, and yn are scalar values in vector y.

The training process involves sequentially training weak learners fin on data (Xm,ym ), sampled from (X,y) with replacement. Sample weights w are updated to place emphasis on previous mistakes. A model confidence measure m is assigned to the mth weak learner to blend it with the ensemble. This process is illustrated for a small ensemble (M=4) in Figure 2.12.

The training steps are:

Initialize sample weights as wnl =I for n=l..N.

For m=l..M, calculate:

Sample probabilities pn = wnm / In wnm for all n.

Sample data (Xm ,ym ) by selecting N samples from (X,y) using pn

Fit weak learner fin to (Xm ,ym ).

Compute loss in for each sample using predictions y’ from fin and adhering to equation (3).

Compute average loss i- and terminate if i- 0.5, as indicated in step 4.

Calculate confidence measure m = i- I (I - i-).

Update sample weights wnm+ I = wnm m I-in

Step 6 emphasizes larger differences between observations and predictions in the updated weights. This trains subsequent weak learners to focus on previous model mistakes.

Predictions for a given input x* are generated by considering predictions from each weak learner and calculating an ensemble prediction based on the confidence measures. The smallest Kth machine’s prediction that meets a certain condition becomes the ensemble prediction, noted as yK. This value represents a weighted median of the predicted values ym.

D. Gradient Boosting Regressor

Gradient Boosting is a robust boosting algorithm that fuses weak learners into potent ones by minimizing a loss function, such as mean squared error or cross-entropy, of the preceding model’s predictions using gradient descent. In each iteration, it calculates the gradient of the loss function concerning the current ensemble’s predictions and then trains a new weak model to minimize this gradient. The new model’s predictions are integrated into the ensemble, and this cycle continues until a stopping condition is met.

In contrast to AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting doesn’t modify training instance weights. Instead, it trains each predictor using the residual errors from the previous one as labels. A technique called Gradient Boosted Trees employs a base learner like CART (Classification and Regression Trees). The process is illustrated in Figure 2.13, where an ensemble of M trees is trained. Tree l is created using feature matrix X and labels y. The predictions yl(hat) help compute the residual errors r1. Tree2 is trained using X and the r1 residuals as labels. The process repeats for all M trees.

A significant parameter in this method is the “Shrinkage,” where the prediction of each tree is scaled after being multiplied by the learning rate (eta) within the range of Oto 1. Balancing eta and the number of estimators is vital reducing the learning rate should be compensated by increasing estimators to maintain model performance.

The Gradient Boosting Algorithm’s steps are as follows:

Stq-,: ] :Given input X and target Y with N samples, aim to learn the function f(x) that maps X to y. Boosted trees comprise the sum of trees. The loss function quantifies the discrepancy between actual and predicted values.

Sk:p 2:The objective is to minimize the loss function L(f) with respect to f

J: Steepest Descent:For M-stage gradient boosting, steepest descent identifies where is a constant step length, and gim is the gradient of loss function L(f).

Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) is a widely used machine learning algorithm that merges weak predictive models, usually decision trees, to create a robust predictive model. Here are advantages and disadvantages of employing Gradient Boosting Regressor.

VII. Results and Discussion

This portion provides an overview of the outcomes and a discussion of the conducted experiments.

A. Machine Learning Models

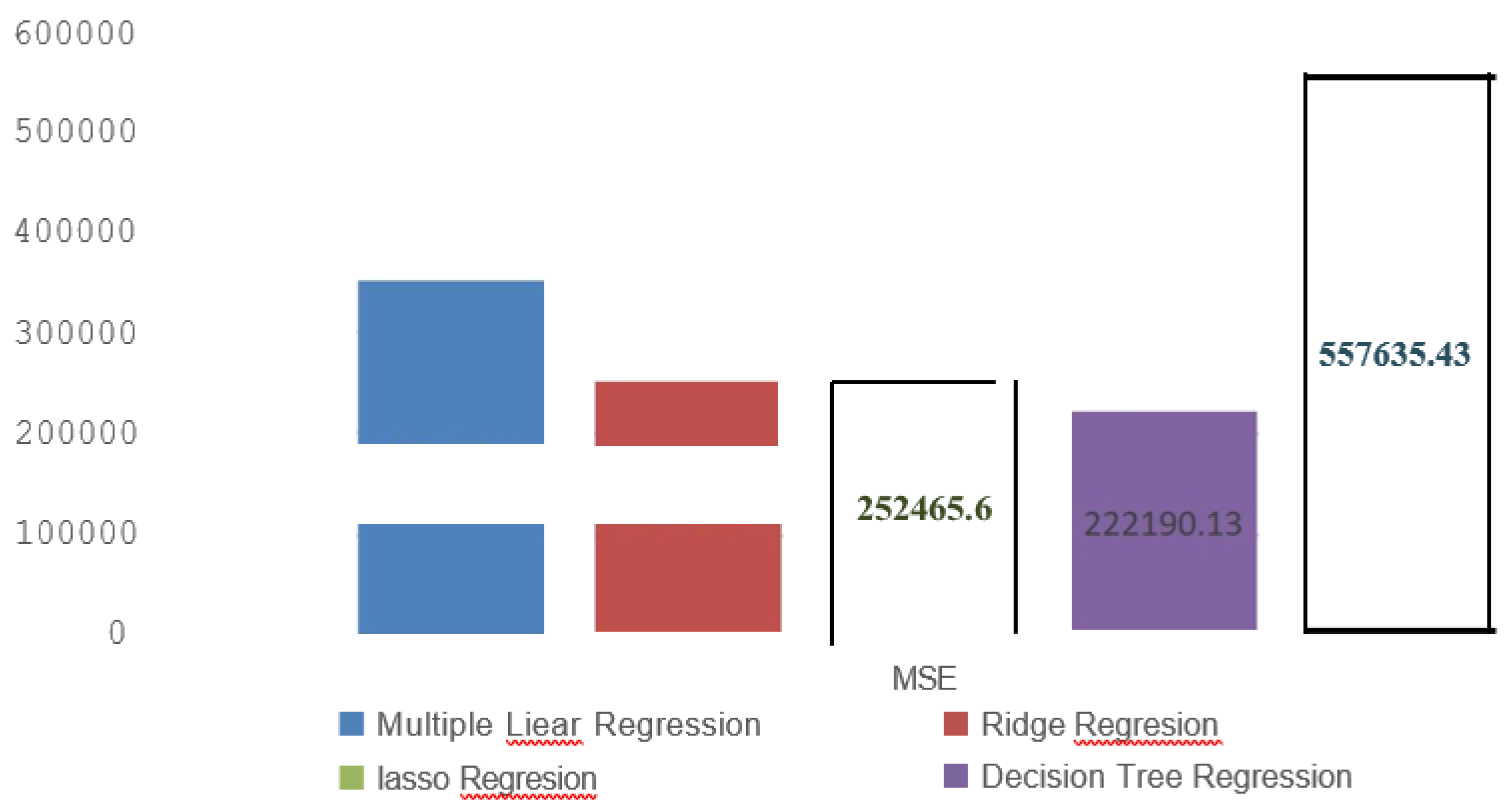

The machine learning models employed in this study involved creating simple forecasts based on the assumption of slow changes or persistence in daily solar PV power production. As a result of these simplistic assumptions, the performance of these models was not anticipated to be highly accurate. This observation is evident from the outcomes presented in figure-2,3,4,5 depicting the Mean Square Error(MSE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error(MAE) and the Coefficient ofDetermination(W’2) for model evaluations.

The MSE is the average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values. It’s a measure of the average magnitude of prediction errors. A lower MSE is preferable, indicating that the algorithm’s predictions are closer to the actual values. In the hypothetical comparison, Decision Tree Regression(DTR) demonstrates the best performance with the lowest MSE, indicating that its predictions have the smallest squared errors on average. Decision Tree Regression, with the highest MSE, has predictions with larger squared errors on average.

Figure 2.

MSE comparison of Machine Learning models.

Figure 2.

MSE comparison of Machine Learning models.

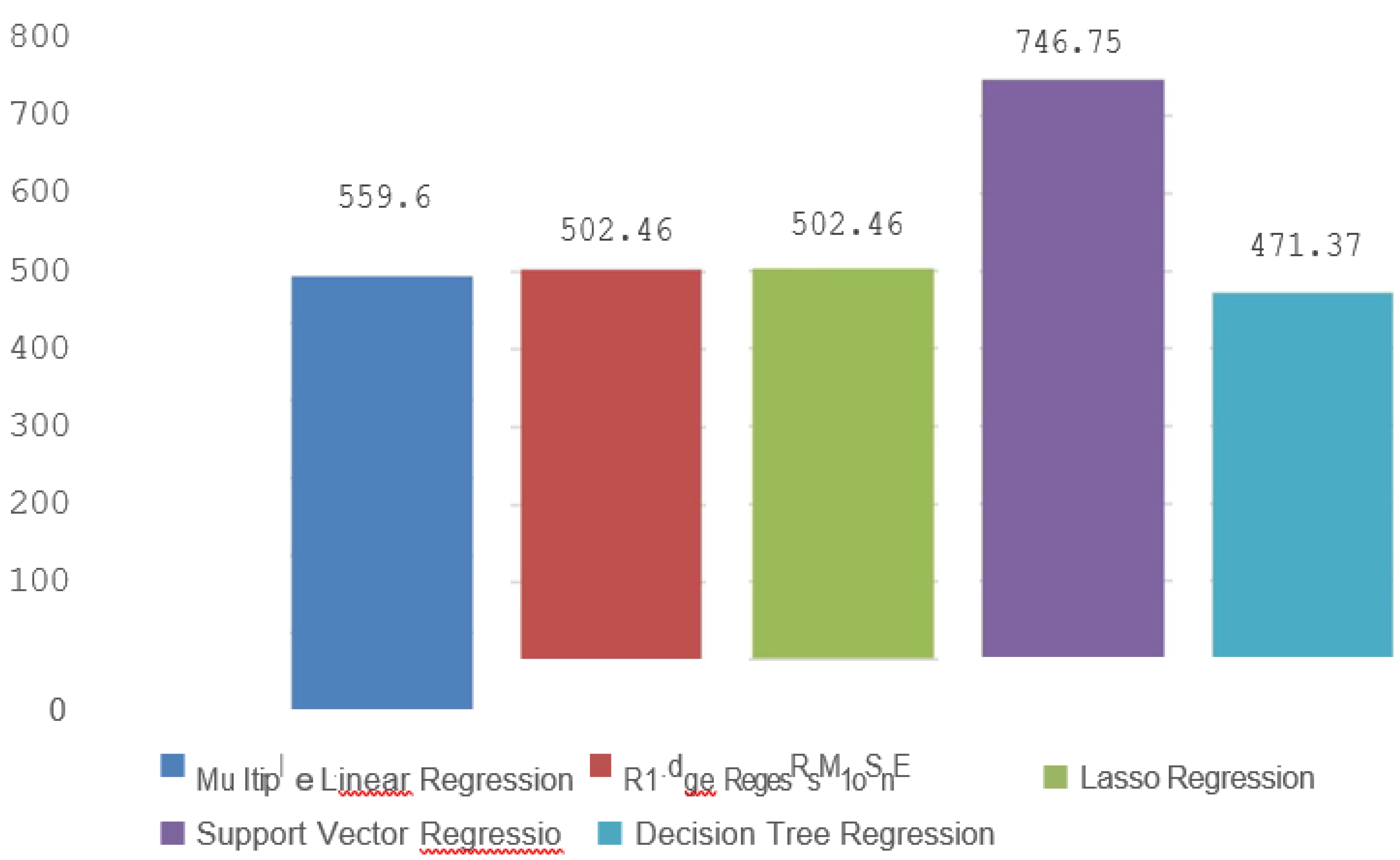

The RMSE is a widely-used metric that represents the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and actual values. A lower RMSE indicates better predictive accuracy, as it signifies that the algorithm’s predictions are closer to the true values. In the hypothetical comparison, Decision Tree Regression(DTR) has the lowest RMSE, suggesting that it is able to capture the data’s variations more accurately than the other algorithms. On the other hand, Support Vector Regression(SVR) has the highest RMSE, suggesting that its predictions exhibit more variability from the actual values.

Figure 3.

RMSE comparision of Machine Learning modes.

Figure 3.

RMSE comparision of Machine Learning modes.

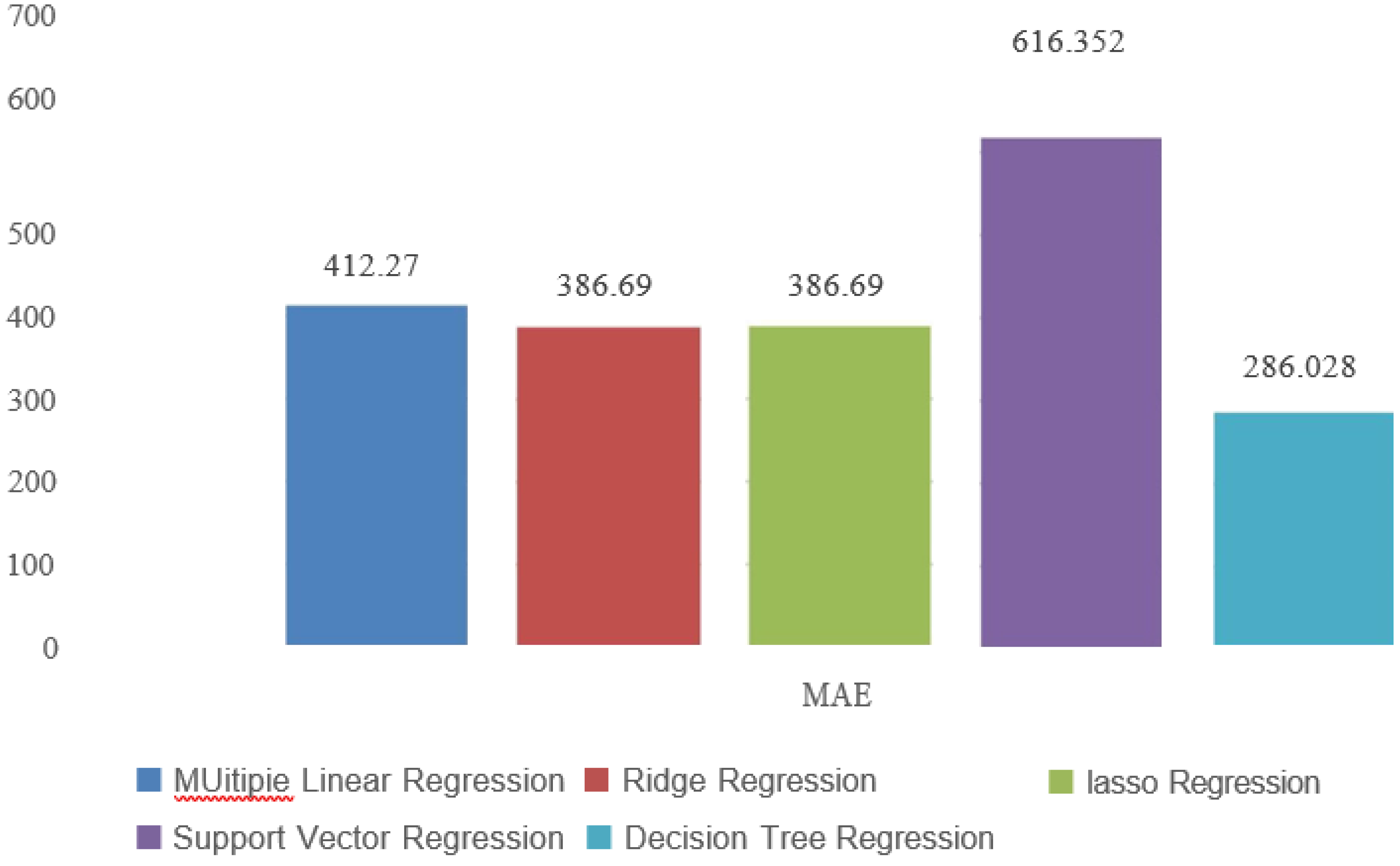

The MAE measures the average absolute differences between predicted and actual values. Unlike squared error metrics, MAE gives equal weight to all errors regardless of their magnitude. A lower MAE suggests better predictive accuracy. In our comparison, Decision Tree Regression(DTR) has the lowest MAE, indicating that its predictions are, on average, closer to the true values compared to the other algorithms. Support Vector Regression has the highest MAE, implying that its predictions deviate more in terms of absolute value.

Figure 4.

MAE comparison of Machine Leaming models.

Figure 4.

MAE comparison of Machine Leaming models.

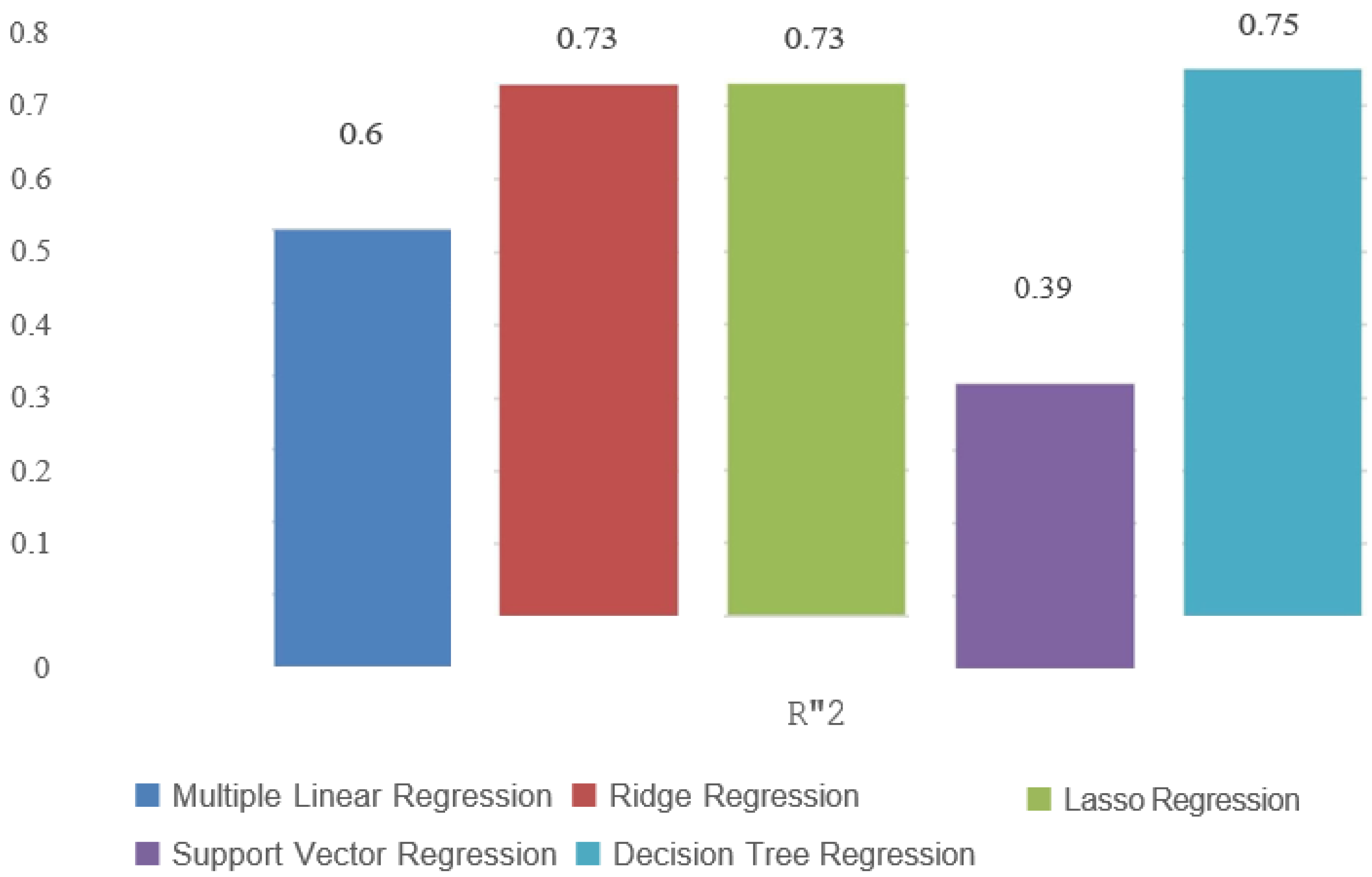

The R-squared represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. A higher R-squared value indicates a better fit of the model to the data. In the hypothetical comparison, SVR has the highest R-squared value, suggesting that it explains a larger proportion of the variance in the target variable compared to the other algorithms. This indicates that the Decision Tree Regression(DTR) model captures more of the underlying relationships within the data. Conversely, Support Vector Regression(SVR) has the lowest R-squared, implying that it might not be capturing the complex patterns present in the data as effectively as the other algorithms.

Figure 5.

W’2 comparison of Machine Learning Models.

Figure 5.

W’2 comparison of Machine Learning Models.

In this hypothetical scenario, we can observe that:

- -

Decision Tree Regression(DTR) has the lowest RMSE, MSE, and MAE values, indicating better predictive accuracy compared to other algorithms.

- -

MLR, Ridge, and Lasso have fairly similar performance in terms ofRMSE, MSE, and MAE, with Ridge slightly outperforming Lasso.

- -

Support Vector Regression(SVR) has higher RMSE, MSE, and MAE values, indicating that it might not be capturing the underlying patterns as effectively as the linear-based methods or SVR.

- -

Decision Tree Regression also has the highest R-squared value, implying a better fit to the data compared to other algorithms.

In summary, the choice of regression algorithm depends on the specific trade-offs you want to make between accuracy, interpretability, and complexity. Decision Tree Regression(DTR) seems to perform well in this hypothetical scenario across all metrics, indicating a balance between accurate prediction and model fit. However, it’s important to validate these findings on real-world data and consider other factors such as model interpretability and computational complexity before making a final decision.

B. Ensemble Learning Models

Ensemble methods in machine learning consistently outperform individual ML models, showcasing their remarkable ability to enhance predictive capabilities. These techniques harness the collective intelligence of diverse models, resulting in a significant boost in accuracy and a deeper understanding ofintricate data relationships. The synergy achieved through ensemble methods enables them to effectively navigate complex patterns that might elude standalone models.

Consequently, ensemble techniques stand as a formidable approach in elevating the performance and reliability of predictive modeling, showcasing their superiority in the realm of machine learning.As a result of these simplistic assumptions, the performance ofthese models was not anticipated to be highly accurate. This observation is evident from the outcomes presented in figure-6,7,8,9 depicting the Mean Square Error(MSE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error(MAE) and the Coefficient ofDetermination(W’2) for model evaluations.

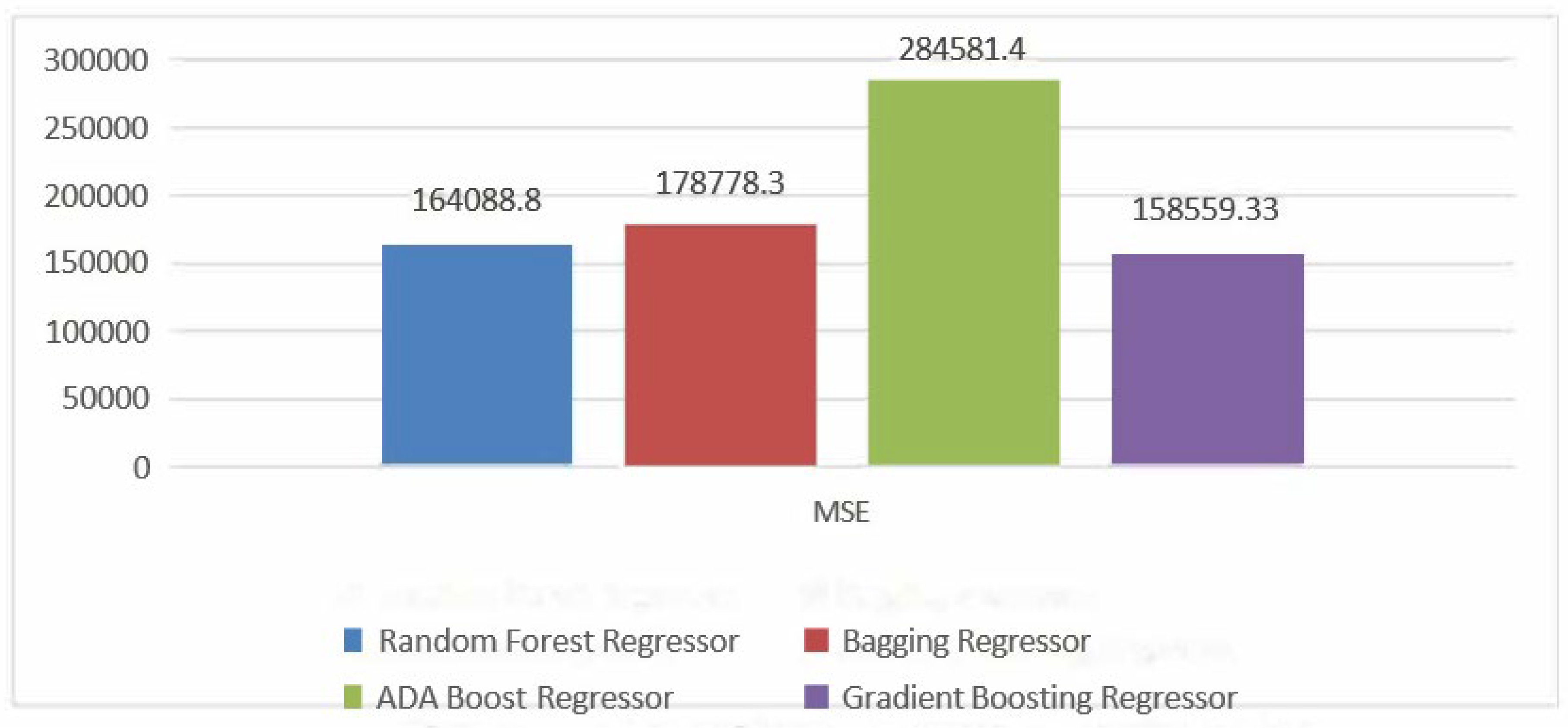

The MSE is the average ofthe squared differences between predicted and actual values. It’s a measure ofthe average magnitude ofprediction errors. A lower MSE is preferable, indicating that the algorithm’s predictions are closer to the actual values. In the hypothetical comparison from figure-6, Gradient Boostig Regressor(GBR) demonstrates the best performance with the lowest MSE, indicating that its predictions have the smallest squared errors on average. ADA Boost Regressor, with the highest MSE, has predictions with larger squared errors on average.

Figure 6.

MSE comparision ofEnsemble Learning models.

Figure 6.

MSE comparision ofEnsemble Learning models.

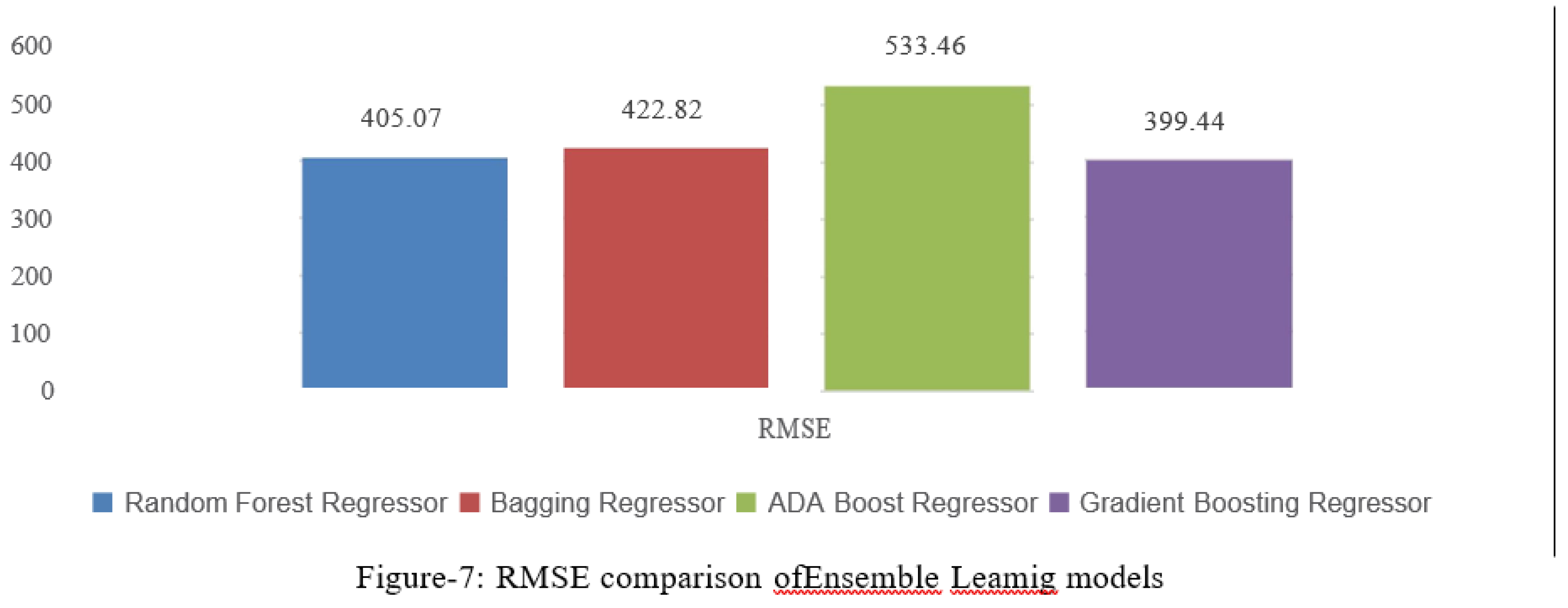

RMSE is a widely-used metric that represents the square root ofthe average squared differences between predicted and actual values. A lower RMSE indicates better predictive accuracy, as it signifies that the algorithm’s predictions are closer to the true values. In the hypothetical comparison from figure-7, Gradient Boosting Regressor has the lowest RMSE, suggesting that it is able to capture the data variations more accurately than the other algorithms. On the other hand, ADA Boost Regressor has the highest RMSE, suggesting that its predictions exhibit more variability from the actual values.

Figure 7.

RMSE comparison ofEnsemble Leamig models.

Figure 7.

RMSE comparison ofEnsemble Leamig models.

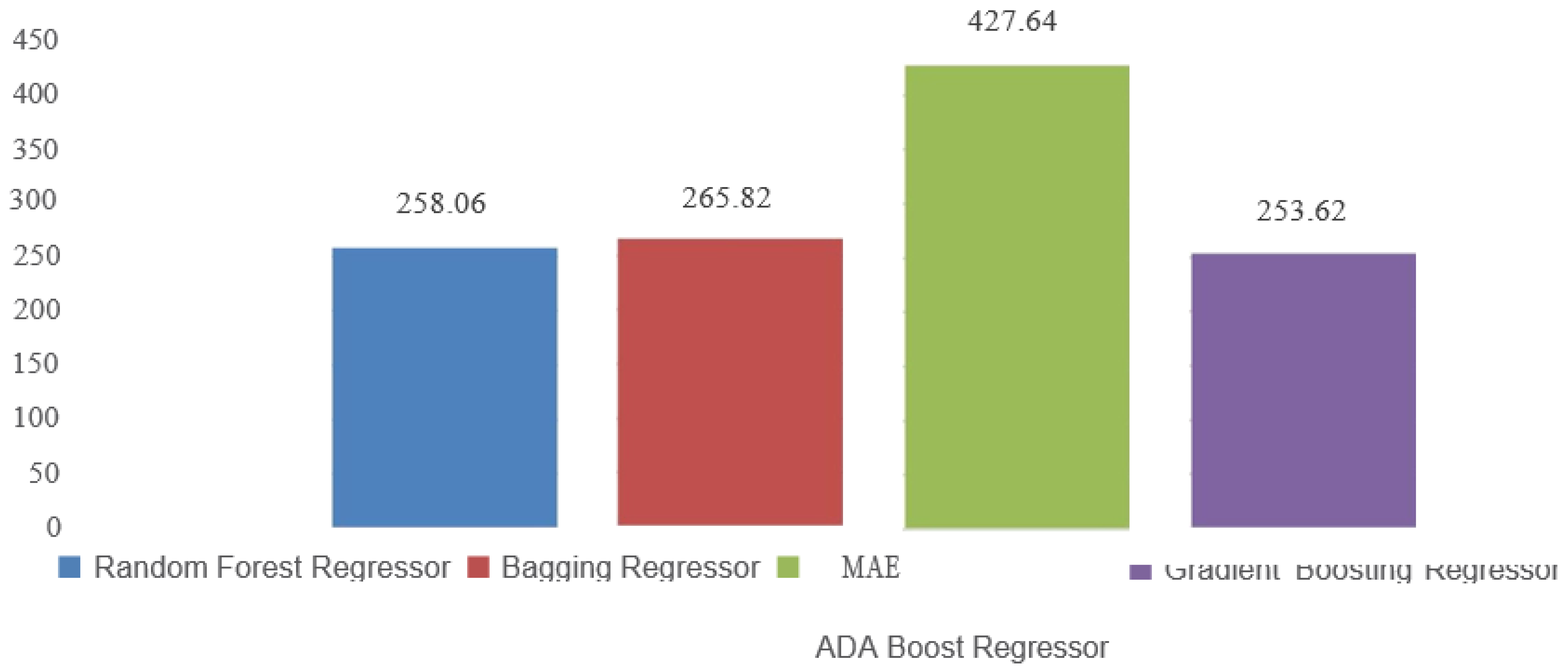

MAE measures the average absolute differences between predicted and actual values. Unlike squared error metrics, MAE gives equal weight to all errors regardless of their magnitude. A lower MAE suggests better predictive accuracy. In our comparison from figure-8, Gradient Boosting Regressor has the lowest MAE, indicating that its predictions are, on average, closer to the true values compared to the other algorithms. ADA Boost Regressor has the highest MAE, implying that its predictions deviate more in terms of absolute value.

Figure 8.

MAE comparision of Ensemble Leaming models.

Figure 8.

MAE comparision of Ensemble Leaming models.

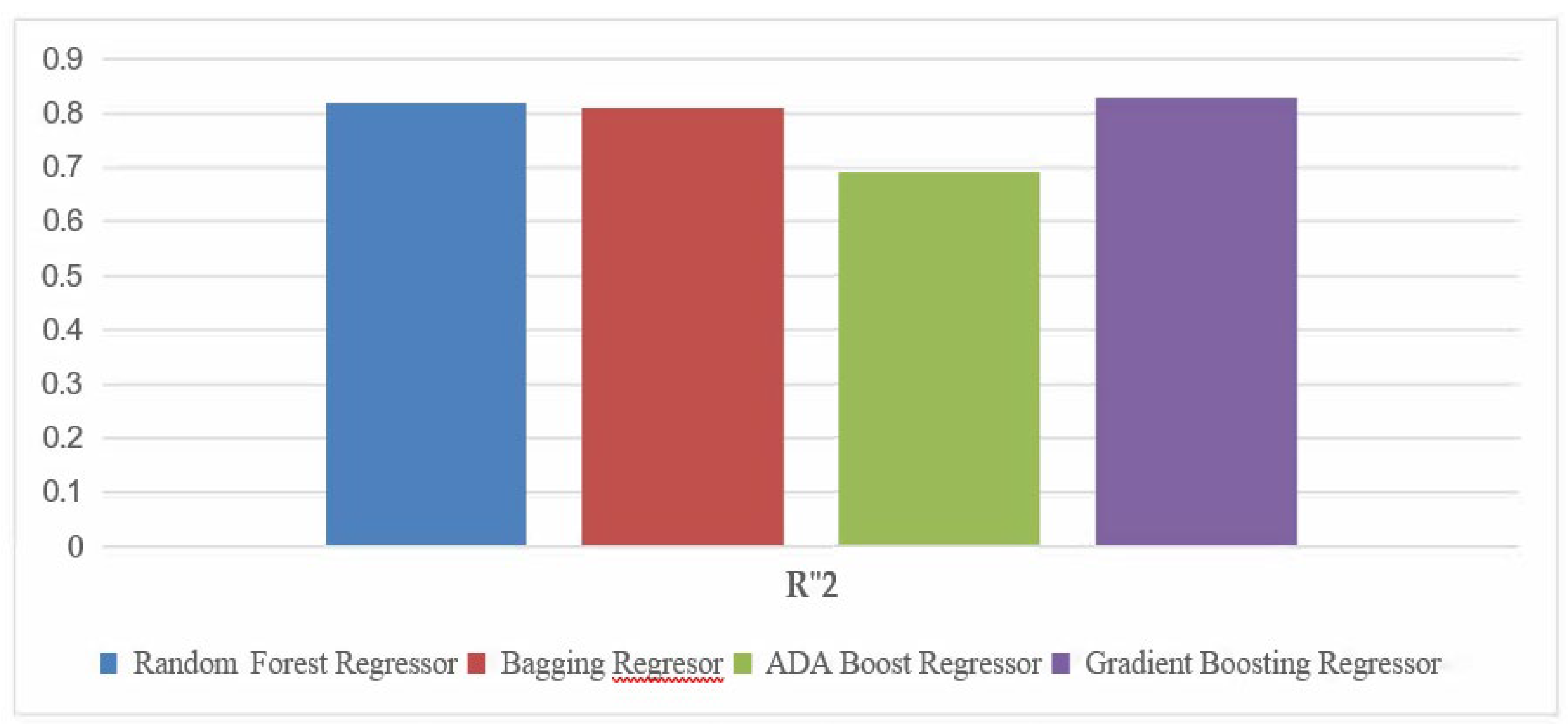

R-squared represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. A higher R-squared value indicates a better fit of the model to the data. In the hypothetical comparison, SVR has the highest R-squared value, suggesting that it explains a larger proportion of the variance in the target variable compared to the other algorithms. This indicates that the SVR model captures more of the underlying relationships within the data. Conversely, Decision Tree Regression has the lowest R-squared, implying that it might not be capturing the complex patterns present in the data as effectively as the other algorithms.

Figure 9.

W’2 comparision ofEnsemble Learning Models.

Figure 9.

W’2 comparision ofEnsemble Learning Models.

In this hypothetical scenario, we can observe that:

- -

Gradient Boosting Regressor has the lowest RMSE, MSE, and MAE values, indicating better predictive accuracy compared to other algorithms.

- -

ADA Boost Regressor has higher RMSE, MSE, and MAE values, indicating that it might not be capturing the underlying patterns as effectively as the linear-based methods or SVR.

- -

Gradient Boostig Regressor also has the highest R-squared value, implying a better fit to the data compared to other algorithms.

In summary, the choice of regression algorithm depends on the specific trade-offs you want to make between accuracy, interpretability, and complexity. Decision Tree Regression(DTR) seems to perform well in this hypothetical scenario across all metrics, indicating a balance between accurate prediction and model fit. However, it’s important to validate these findings on real-world data and consider other factors such as model interpretability and computational complexity before making a final decision.

Comparison

In this section we will compare all performance metrics from the results section. In given below table all the machine learning and ensemble model performance metrics are compared and best method is concluded based on the the Mean Square Error(MSE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error(MAE) and the Coefficient ofDetermination(W’2) for model evaluations.

Table 2.

comparison of performance metrics of machine learning and Ensemble Learning models.

Table 2.

comparison of performance metrics of machine learning and Ensemble Learning models.

| MODEL |

MSE |

RMSE |

MAE |

W’2 |

| MULTIPLE LINEAR REGRESSION |

352465.7 |

559.6 |

412.27 |

0.6 |

| RIDGE REGRESSION |

252465.6 |

502.46 |

386.69 |

0.73 |

| LASSO REGRESSION |

252465.6 |

502.46 |

386.69 |

0.73 |

| SUPPORT VECTOR REGRESSION |

557635.43 |

746.75 |

616.352 |

0.39 |

| DECISION TREE REGRESSION |

222190.13 |

471.370 |

286.028 |

0.75 |

| RANDOM FOREST REGRESSION |

164088.8 |

405.07 |

258.06 |

0.82 |

| BAGGING REGRESSOR |

178778.3 |

422.82 |

265.82 |

0.81 |

| ADA BOOST REGRESSOR |

284581.40 |

533.46 |

427.64 |

0.69 |

| GRADIENT BOOSTING REGRESSOR |

158559.33 |

399.44 |

253.62 |

0.83 |

From the table we can conclude that the ensemble models performed better compared to the normal machine learning methods from the Table 9.1 we can say that Gradient boosting regressor is best model for this data set because it has high R6/\2 value of 0.83 and low MSE,RMSE and MAE values of 158559.33, 399.4 and 253.62.

VIII. Conclusion

This projected presented a comprehensive and comparative anlysis on Machine Learning (ML) based models on solar power forecasting. The work provided an overview of factors affecting solar PV power forecasting. These factors are weather conditions and forecasting horizons. From the weather conditions aspect, the effectiveness of solar PV systems is dependent on many factors including the amount of solar irradiance and ambient temperature which are subject to weather conditions. Accurate weather forecasting can be used to improve the ability to predict the power output of PV systems, and the meteorological variables that have the greatest impact on PV power can vary depending on the location of the solar power plant. ML algorithms used in solar PV power forecasting and a description of commonly used performance metrics used for solar PV power forecasting. The presented ML algorithms are Multiple Linear Regression, Ridge regression, Lasso Regression, Decision Tree Regression, Support Vector Regression, Ensemble models such as Random Forest, Bagging Regressor, ADA Boost regressor and Gradient Boosting Regressor. The commonly used ML performance evaluation metrics are provided in chapter 3. Finally, a comparison of ML models based on performance metrics compared against each other. Using the solar PV power forecasting performance metrics presented in TABLE 9.1, findings from the simulation work show that ensemble models performed better than the machine learning methods. The gradient boosting regressor model has high R/\2 value of 0.83 and low RMSE, MSE, MAE values of 399.44, 159559.33, 253.62 compared to all models and this method is concluded as best model for solar power forecasting.

IX. Future Scope

In the future, there are several areas that could be explored further in the field of photovoltaic (PV) forecasting. The accuracy of PV forecasting is essential for ensuring the reliable and efficient operation of the electric grid or off-grid PV systems. Numerical weather prediction (NWP) models are one of the key factors in the accuracy of PV forecasting. To improve PV forecasting, future work should focus on enhancing NWP models by incorporating additional data sources and utilizing advanced machine learning algorithms. Additionally, developing more sophisticated physical models of atmospheric processes could also improve the accuracy of PV forecasting. As the use of PV systems for electricity generation continues to increase, there is an increasing need for accurate and

reliable PV forecasting. This will require the development of advanced data preprocessing techniques that can handle large and complex datasets. In addition, Time series forecasting plays a crucial role in solar power forecasting by leveraging historical data to predict future solar energy generation. It enables operators to optimize grid management, plan for fluctuations in solar output, and improve the overall efficiency of solar power plants. Various time series forecasting methods, such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), exponential smoothing (ETS), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and support vector regression (SVR), are commonly employed to model and predict solar power generation patterns accurately and enable effective decision-making in the renewable energy sector.

References

- waone Gaboitaolelwe, Adamu Murtala Zungeru, Abid Yahya,” Machine Learning Based Solar PhotovoltaicPower Forecasting: A Review and Comparison”. [CrossRef]

- Rai, A. Srivastava, and K. C. Jana, “An empirical analysis of machine learning algorithms for solar power forecasting in a high dimensional uncertain environment,” IETE Tech. Rev., pp. 1-16, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghazi and K. Ip, “The effect ofweather conditions on the efficiency ofPV panels in the southeast ofU.K.,” Renew. Energy, vol. 69, pp. 50-59, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Comprehensive examination of solar panel design: A focus on thermal dynamics.

- Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, J. Kleissl, C. A. Gueymard, H. T. C. Pedro, and C. F. M. Coimbra, “History and trends in solar irradiance and PV power forecasting: A preliminary assessment and review using text mining,’’ Sol. Energy, vol. 168, pp. 60-101, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Leva, A. Dolara, F. Grimaccia, M. Mussetta, and E. Ogliari, “Analysis and validation of 24 hours ahead neural network forecasting of photovoltaic output power,” Math. Comput. Simul., vol. 131, pp. 88-100, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. V. Pombo, H. W. Bindner, S. V. Spataru, P. E. S0rensen, and P. Bacher, “Increasing the accuracy of hourly multi-output solar power forecast with physics-informed machine learning,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 3, p. 749, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, H., Hodge, B.-M., & Karimzadeh “Solar Power Forecasting: A Review of State-of-the-Art Methodologies” (2020). [CrossRef]

- Inman, R. H., & Pedro, H. T. C.”Machine Leaming for Solar Power Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review” (2020). [CrossRef]

- Amjady, N., & Keynia, “An Overview of Solar Power Forecasting and Prediction Intervals” (2020).

- Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 131, 110029. [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, J., & Fotuhi-Firuzabad,”Short-Term Solar Power Forecasting Using Machine Leaming Techniques” (2020), Energy Reports, 6, 1738-1753. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Strategic placement of charging stations for enhanced electric vehicle adoption in San Diego, California. Journal of Transportation Technologies, 14(1), Article 141005. [CrossRef]

- Swami, G., Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). PV capacity evaluation using ASTM E2848: Techniques for accuracy and reliability in bifacial systems. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, 15(9), Article 159012. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Numerical Weather Data.

Table 1.

Numerical Weather Data.

| Variable Name |

NWP |

Unit |

temperature_2_m_above_gnd relative_humidity_2_m_above_gn d

mean_sea_level_pressure_MSL total_precipitation_sfc

snowfall amount sfc

- -

total cloud cover sfc

- - -

high_cloud_cover_high_cld_lay

medium cloud cover mid cld la

- - - - -y low_cloud_cover_low_cld_lay

shortwave radiation backwards s

- - -

fc

wind_speed_ IO_m_above_gnd wind_direction_ IO_m_above_gnd wind_speed_80_m_above_gnd wind_direction_80_m_above_gnd

wind_speed_900_mb wind direction 900 mb

- - -

wind_gust_ IO_m_above_gnd

angle_of_incidence zenith

azimuth

generated_power kw |

Temperature At 2m Above Ground Relative Humidity At Above Ground

Mean Sea Level Pressure Total Precipitation Snowfall Amount

Total Cloud Cover High Cloud Cover Medium Cloud Cover

Low Cloud Cover

Short Wave Radiation Backwards

Wind Spedd At IOm Above Ground Wind Direction At IOm Above Ground Wind Speed 80m At Above Ground Wind Direction At 80m Above Ground

Wind Speed Wind Direction

Wind Gust At IOm Above Ground Angle Of Incidence

Zenith Azimuth

Generated power |

C

%

%

%

%

%

%

%

%W/m2

mis mis mis mis

mis mis mis

degree degree degree

KW |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

J: Steepest Descent:For M-stage gradient boosting, steepest descent identifies where is a constant step length, and gim is the gradient of loss function L(f).

J: Steepest Descent:For M-stage gradient boosting, steepest descent identifies where is a constant step length, and gim is the gradient of loss function L(f).