1. Introduction

Cortinarius sinensis L.H. Sun, T.Z. Wei & Y.J. Yao, which has been revised to

Calonarius sinensis [

1], is a well-known edible mushroom endemic in China. This famous mushroom is known as the "Helan Mountain Treasure" because of its large individuals, thick flesh, mellow taste, and rich nutrition. It is also a special gift given by local people to guests [

2]. This wild edible mushroom has a local name “Helan Mountain Zimogu” because of its purplish brown color in the Alashan League area of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, which indicated the long consume history of this mushroom and favorited by local people.

C. sinensis is the most popular edible mushroom in local regions, its price is becoming expensive because the wild resources have been decreasing. Many reasons resulted in the decline of its wild resources, firstly,

C. sinensis is an ectomycorrhizal fungus which form symbiosis with

Picea crassifolia Kom. [

3], it has not been successfully domesticated and cultivated so far; secondly, driven by economic interests, many local people and people from other places illegally enterred into Helan Mountain National Reserve during the fruting season to hunt the fruitbodies,

C. sinensis hunters even lived in simple tent hiding in dangerous steeps for few days, which resulted in the excessive collection of

C. sinensis wild resources ; thirdly,

C. sinensis hunters collected all sizes of fruitbodies including unmatured fruitbodies with unreleased spores, which resulted in the completely lost of the opportunity to reproduce, and the output declines year by year; fourthly, the moss layer which is rich under

P. crassifolia forest has been destroyed in big areas, resulting in the loss of humus and physical protection for the fruiting of

C. sinensis, in the continuous destruction of the ecological environment on which

C. sinensis depends; last but not least, climate change is playing the important role in the decline of

C. sinensis production, such as the less precipitation in winter and in spring, after many efforts only few fruitbody samples have been collected during the last two years (personal communication with local forest rangers of Helan Mountain National Reserve).

At present, C. sinensis have not been artificially cultivated, and wild resources alone are far from meeting the market demand. In the Alashan League area of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, there are many “Zimogu” noodle restaurants, which are popular in locals and tourists and run year-round, which means a large number of “Zimogu” are needed and stored during fruiting season, C. sinensis therefore from other distributed regions, such as Qilian Mountain of Qinghai Province and Gansu Province have been sold to the local markets of the Alashan League area of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It is interesting that the fresh fruitbodies of C. sinensis from Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain have large price differences, Helan Mountain Zimogu is three to six times more expensive than C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain, which resulted in the trade fraud in the local markets. C. sinensis hunters from Qilian Mountain transported the fresh fruitbodies overnight to the local market of Helan Mountain in Inner Mongolia, the traders sold them as Helan Mountain Zimogu. It is said by the local consumers from Inner Mongolia that Helan Mountain Zimogu tastes much better than C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain, there is yet no scientific data to prove this issue.

Determining the potential geographic distribution of one species and predicting how climate change would affect its geographic range are necessary and meaningful. The maximum entropy (MaxEnt) model has been widely applied in conservation biology, impact of global climate change on species distribution, and progress chemical biology and other fields [

4]. The protection and sustainable utilization of some edible mushrooms in China, including three in four macrofungi which were officially listed as key protected species by the State Council In July 2021, such as

Tricholoma matsutake [

5]

, Leucocalocybe mongolica [

6], and

Ophiocordyceps sinensis [

7], have been studied using MaxEnt model, which can be used as references for studies on other mushroom species. In this study, we study the potential geographic distribution of

C. sinensis and predict how climate change would affect its geographic range using MaxEnt model, and make its conservation strategies combing the nutrition contents and tast.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maxent Model

2.1.1. Geographic Distribution Data

The geographical distribution data of

C. sinensis was obtained from the published literature [

8].

2.1.2. Climatic Data

Contemporary climate data are based on climate data from 1970 to 2000, including 19 bioclimatic variables and elevation [

9]. The bioclimatic variables and corresponding elevation data[

9] with a spatial resolution of 5 arc minutes (ca. 10 km) were downloaded from the WorldClim database (

http://www.worldclim.org/) and used to map the potential distributions and identify the key variables. The future climate variables from 2021-2040 (2030s), 2041-2060 (2050s) and 2061-2080 (2070s) are selected. Future climate variables for the three periods were selected from the BCC-CSM2-MR model, which is capable of reasonably simulating regional climate change trends in China [

10]. This model can reflect the global energy balance, accurately reflect the complexity of regional climate change in China, and have high simulation accuracy for factors such as atmospheric temperature and precipitation [

11]. Future period data are projected using the four most recent IPCC SSPs (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5), which represent future climate scenarios with low to high carbon emissions, respectively [

12]. Future climate data using SDM Toolbox converted to the ASCII raster grid format in ArcGIS for MaxEnt modeling.

2.1.3. Species Distribution Modeling and Validation

The selected species geographic distribution data and climatic data were entered into the MaxEnt 3.4.4 to model the current and future potential habitats of

C. sinensis for MaxEnt modeling. The model parameters were set as follows: (1) 75 % of the geographical distribution data were randomly selected as training data, and the remaining 25 % were used as testing data (Pra manik et al., 2021); (2) the prediction results of the model were measured by the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC), and the Area Under Curve (AUC) was calculated to improve the accuracy [

13]; it is generally believed that an AUC value between 0.5 and 0.7 indicates a relatively low prediction accuracy of the model; a value between 0.7 and 0.9 represents a medium level of accuracy; and a value greater than 0.9 implies a high level of accuracy [

14,

15]; and the jackknife test was used to measure the contribution and importance of environmental factors to species potential distribution [

16]; (3)cross-validation was set in the replicated run type, and the model was set to run 10 times [

17]; (4) the Cloglog transform as a continuous index of habitat suitability was selected as the output format [

18], which provides predicted probabilities of presence between 0 and 1; (5) other parameters were set by default. Finally, the average result of the 10 cross-validation model runs was taken as the ultimate habitat suitability.

2.1.4. Classification and Area Statistics of Suitable Habitats

The average value of Maxent model after 10 times running (.asc format) was selected and loaded to ArcGIS. Then, the reclassify tool was used to divide the suitable habitats of C. sinensis with natural breaks method, and the suitable habitats of C. sinensis were divided into 5 grades: non, low, medium, high and the most suitable habitats. And calculate the area of suitable habitats for each grade.

2.1.5. Suitable Habitats Migration and Centroid Migration

Meanwhile, in order to clarify the trend of changes in the spatial pattern of suitable habitat under current and future climate scenarios, the Intersect tool in Overlay in Analysis tool was used to analyze the spatial changes of suitable habitat, including unchanged habitat, expansion and contraction.

The suitable habitats under future climate conditions were reclassified and calculated using the mean center tool in ArcGIS toolbox to get the center of the suitable habitats under this climate condition. Using Merge tool of Geoprocessing, the changes of the centroid of the potential suitable habitat of C. sinensis under different climate conditions in the future were obtained compared with the current period, so as to reflect the impact of future climate change on the distribution of the habitat of C. sinensis.

2.2. Nutrition Ingredient Analysis

2.2.1. Sample Collection

The fruitbodies of C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain National Nature Reserve and Helan Mountain National Nature Reserve were collected in August 2023 and identified by the Laboratory of Microbial Resources and Synthetic Biology of the College of Life Sciences, Inner Mongolia University.

The fruitbodies collected from Qilian Mountain was named Q, and its samples were Q1, Q2 and Q3 respectively. The fruitbodies collected from Helan Mountain was named H, and its samples were H1, H2 and H3, respectively. All fruitbodies were dried in an oven at 70°C for 2 hours, then grinded, and filtered through a screen with a diameter of 0.5mm.

2.2.2. Detecting Methods

The relevant nutritional indexes of wild edible fungi were determined according to the national standard method with three replication(

Table 1). The protein content was determined in accordance with GB 5009.5 - 2016 National Food Safety Standard - Determination of Protein in Foods. The fat content was determined in accordance with GB 5009.6 - 2016 National Food Safety Standard - Determination of Crude Fat in Foods. The Crude fiber content was determined in accordance with GB/T 5009.10-2003 determination of crude fiber in vegetable foods. The amino acid content was determined in accordance with GB 5009.124 - 2016 National Food Safety Standard - Determination of Amino Acids in Foods.

2.2.3. Amino Acid Determination Index

The Taste Activity Value (TAV) is the ratio of the amount of each tasting substance in a sample to its corresponding Taste Threshold [

19]. It is generally believed that when TAV is greater than 1, this flavor substance has a significant effect on the taste of the sample. And the larger the value, the greater the contribution. On the contrary, when the ratio is less than 1, it indicates that the taste substance has little contribution to the taste, and the taste effect is not significant. TAV is widely used in the study of various food flavors [

20].

2.3. Data Analysis

The data (dried weight) was analyzed using SPSS, with independent samples t-test conducted. The results of the significance analysis were processed using the Bioinfo Intelligent Cloud(

https://www.bic.ac.cn/BIC/#/).

3. Results

3.1. MaxEnt Modeling

3.1.1. Model Performance Optimization and Calculation

The lambdas files described all the predictor variables for Maxent models of

C. sinensis (Appendix S1). The models for

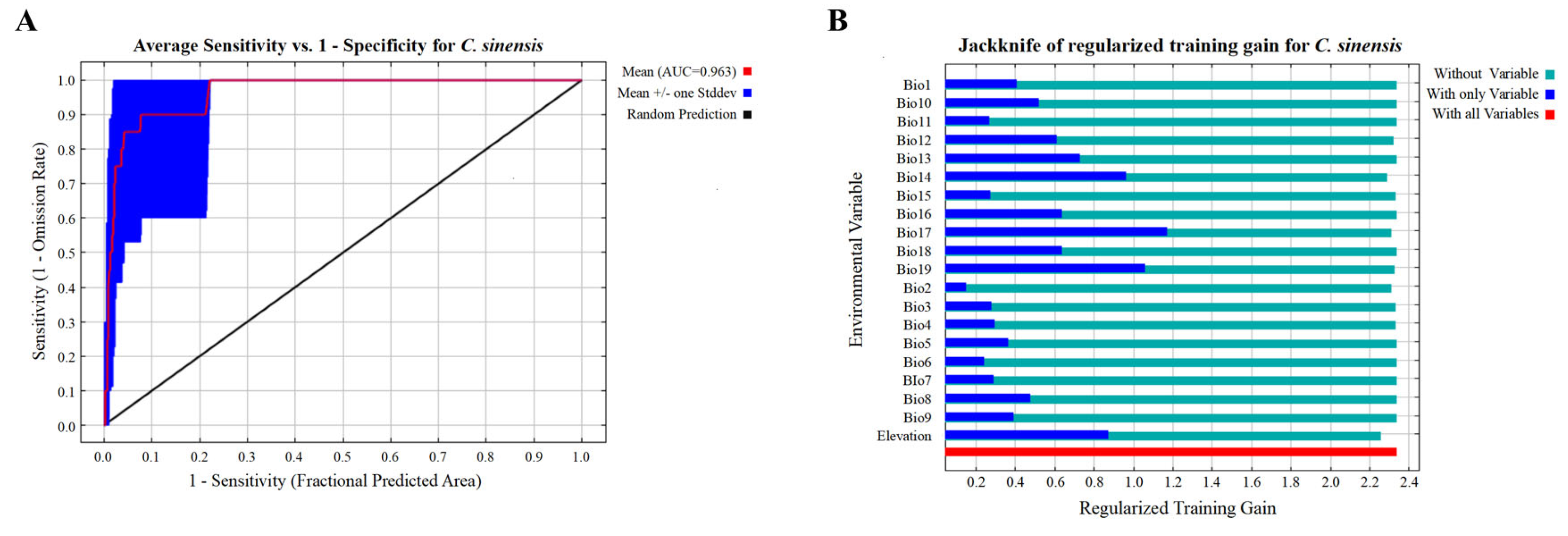

C. sinensis performed excellently, yielding high training and test AUC values, and mean AUC by 10-crossvalidation replicates. The mean AUC value of the ROC curve of the 10-crossvalidation replicates running training set was 0.963, and the AUC value was close to 1 (

Figure 1A). The standard deviation is 0.061. The above results show that MaxEnt model has excellent prediction results and high reliability.

3.1.2. Main Environmental Variables and Response Curves

The geographical distribution of C. sinensis is affected by many environmental factors. Percentage contribution of environmental factors refers to the contribution of environmental factors to the geographical distribution of species when Maxent model analyzing the action scale of environmental variables and the interaction between environmental variables. The Permutation importance of an environmental factor indicates the degree of dependence of the model on the environmental factor in the prediction process, and the higher the score, the greater the contribution of the factor to the species distribution.

In the MaxEnt model, the Jackknife test showed that precipitation of driest quarter had the highest gain, followed by precipitation of coldest quarter and precipitation of driest month when only a single variable has been selected (

Figure 1B). The main environmental variables affecting the distribution of

C. sinensis are precipitation in driest month, elevation and average annual precipitation according to the assessment of percent contribution of various environmental variables to the distribution of

C. sinensis (

Table 2). Among them, precipitation of driest month and elevation had great influence on the distribution of

C. sinensis, contributing 35.9% and 34.3%, annual precipitation contributed 13.7%. According to the evaluation of Permutation importance of various environmental variables affecting the distribution of

C. sinensis, precipitation of coldest quarter and annual precipitation, and precipitation of coldest quarter reached an exaggerated 66.7%. Combining Jackknife test, Percent contribution and Permutation importance, it was concluded that precipitation of coldest quarter, precipitation of driest month, elevation, precipitation of driest quarter and annual precipitation were the main factors affecting the potential suitable distribution of

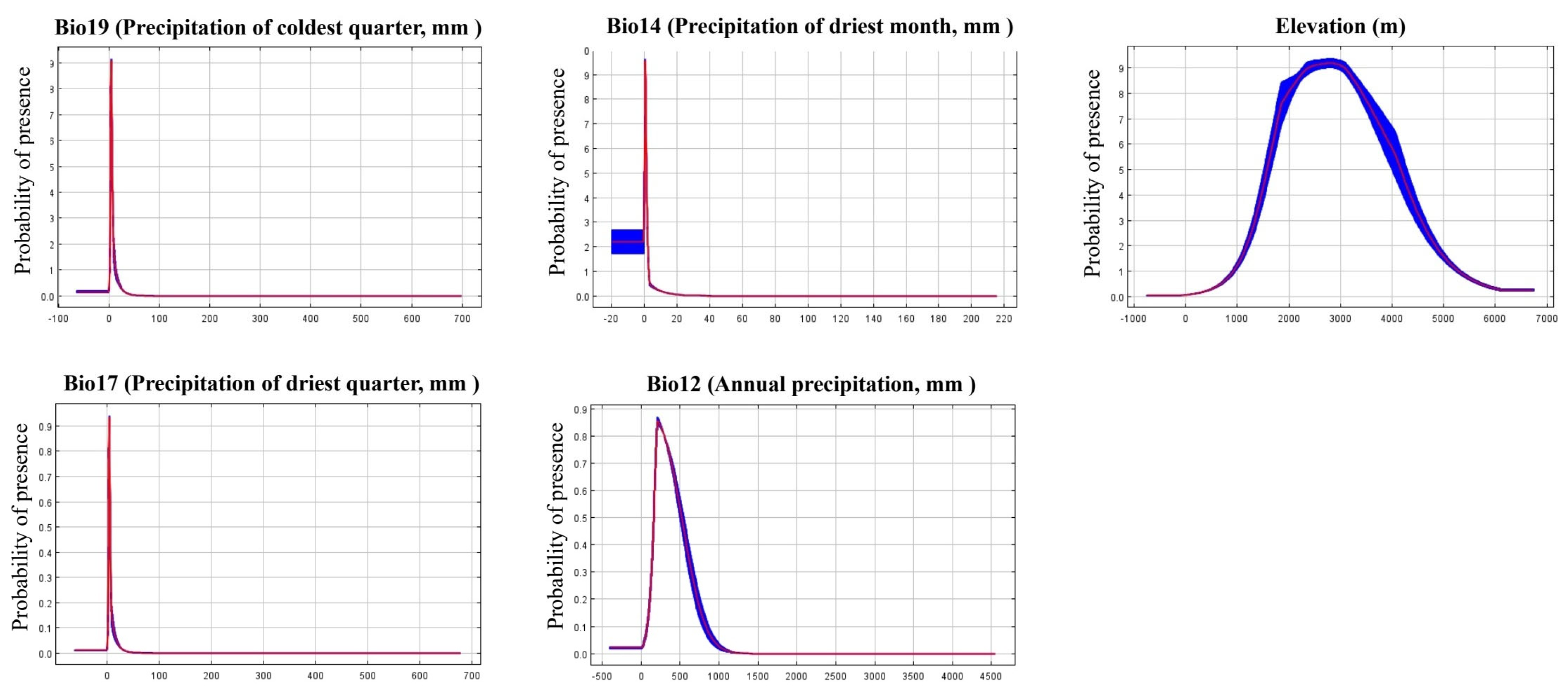

C. sinensis. Based on the MaxEnt model, the response curves of five leading environmental variables to

C. sinensis were obtained (

Figure 2). It was concluded that when precipitation of coldest quarter reached 5.238mm, precipitation of driest month reached 1.059mm, elevation reached 2636m, precipitation of driest quarter reached 5.120mm, and annual precipitation reached 342.6mm, the existence probability of

C. sinensis is high, which is suitable for the distribution of

C. sinensis.

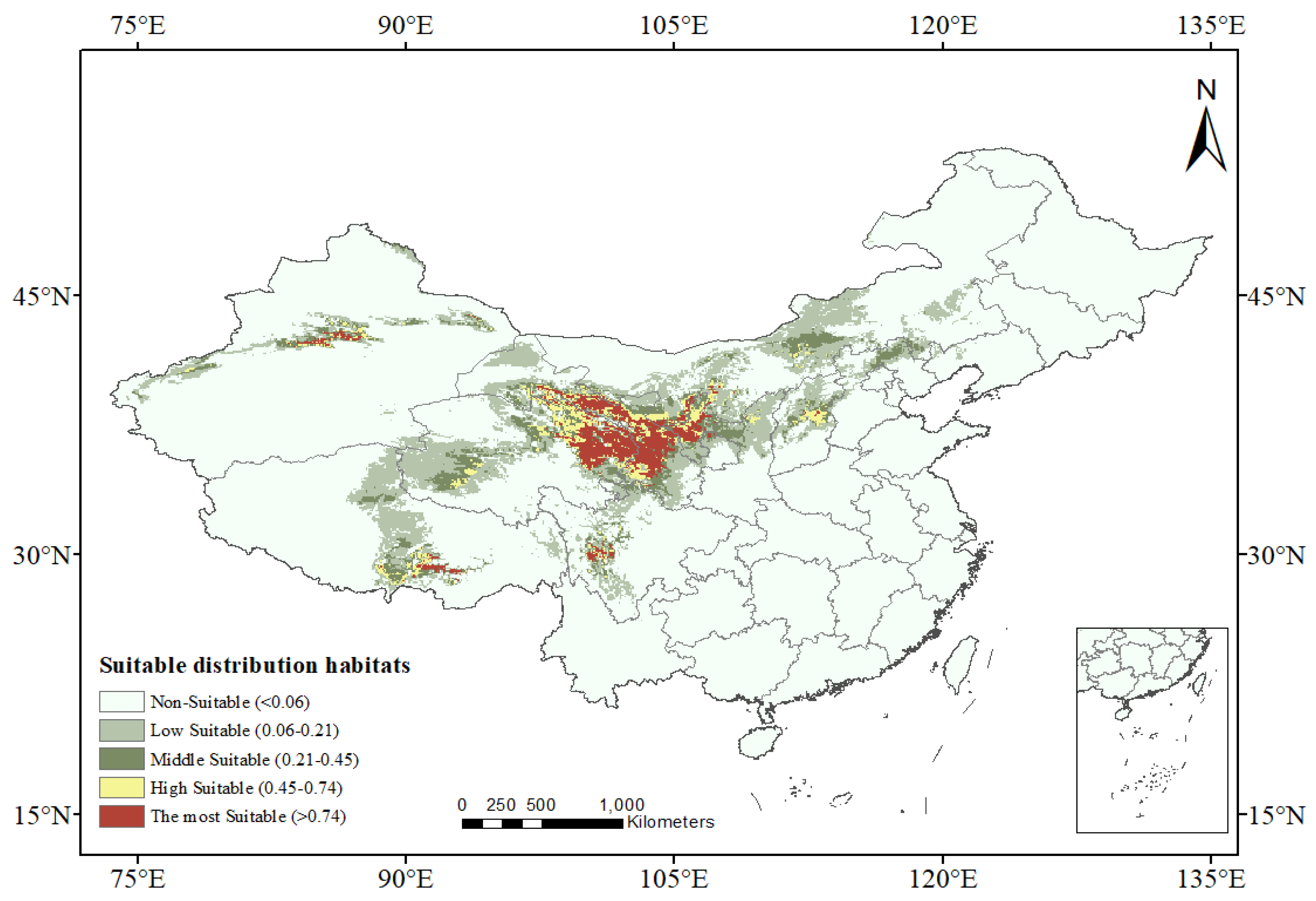

3.1.3. Distribution and Area of Suitable Habitats

The predicted potential geographical distribution showed that the most suitable habitats for the growth of

C. sinensis mainly concentrated in the Helan Mountains and Qilian Mountains, and distributed in the eastern part of Qinghai, the central part of Gansu, the central part of Ningxia, and the border of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia. In addition, western Sichuan, parts of Xinjiang and Tibet also appeared to be suitable habitats for

C. sinensis (

Figure 3).

Based on the probability of presence indicated with P, combing with the actual distribution of C. sinensis, the potential suitable habitats were divided into the following four

grades: the non-suitable habitats (0.00≤P<0.06), the area not suitable for the growth of C. sinensis; the low suitable habitats (0.06≤P<0.21), may be the existence of C. sinensis in this area; the middle suitable habitats (0.21≤P<0.45), C. sinensis could grow in this area, but the growth condition was not good; the high suitable habitats (0.45≤P<0.74), the area was highly suitable for the growth of C. sinensis; most suitable habitats (0.74≤P<1), the most suitable habitats for the growth of C. sinensis. The total areas of the high suitable habitats and the most suitable habitats were about 320,000 square kilometers.

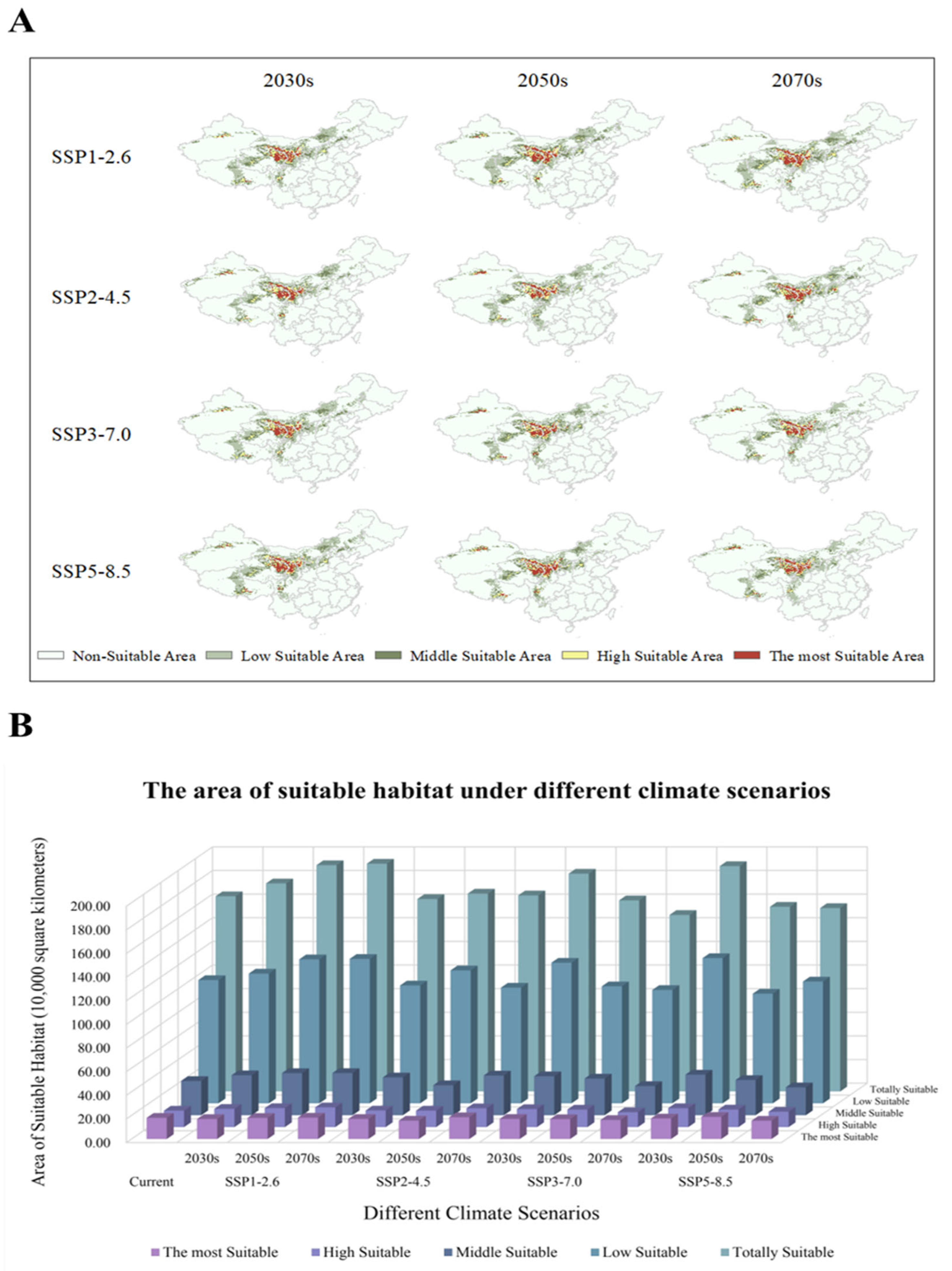

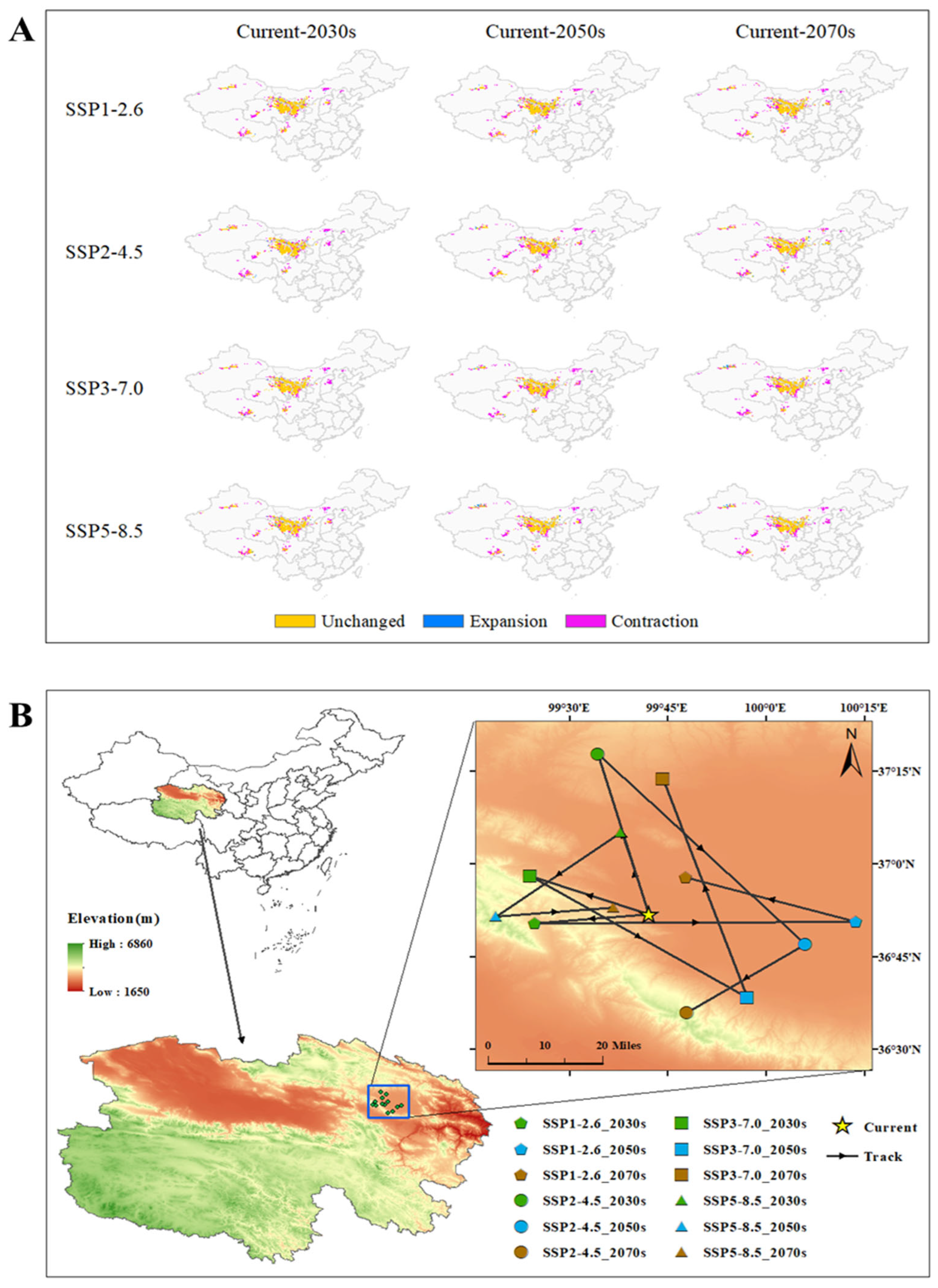

3.1.4. Predicted Distribution of Suitable Habitats under Future Climate Conditions

Under the future climate conditions, the distribution of the suitable areas of

C. sinensis is similar to that of current (

Figure 4A), mainly distributed in eastern Qinghai, central Gansu, Ningxia and western Sichuan. There was no significant change in the area of suitable habitats under different climate scenarios (

Figure 4B). The area of the suitable habitat in the SSP1-2.6 scenario was larger than that in the current scenario, and gradually increased from 2030s to 2070s, it had little change in SSP2-4.5 scenario compared with the current, it decreased gradually from 2030s to 2070s under the SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5. Compared with the current, most of the future high and most suitable areas (P>0.45) overlapped with the present (

Figure 5A), and there is no obvious expansion. The contracted areas were mainly in central Inner Mongolia, central and eastern Shanxi, southwestern Qinghai, southern Gansu and southwestern Tibet. In each of the four climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, SSP5-8.5), each phase (2030s, 2050s, 2070s), the area of contraction exceeds 150,000 square kilometers. Under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, the shrinkage area of 2070s is the largest, with 189,100 square kilometers. The expansion area is concentrated in about 10,000 square kilometers. Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the 2050s will have the largest expansion area of 16,400 square kilometers.

Figure 5B showed the current centroid of the suitable habitat and the future migration of the centroid of the suitable habitat. At present and in the future, the centroid of the suitable habitat is concentrated at the junction of Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. In the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the centroid migrates to the west of the current center of mass during the 2070s. In the remaining scenarios, they are located east of the current centroid.

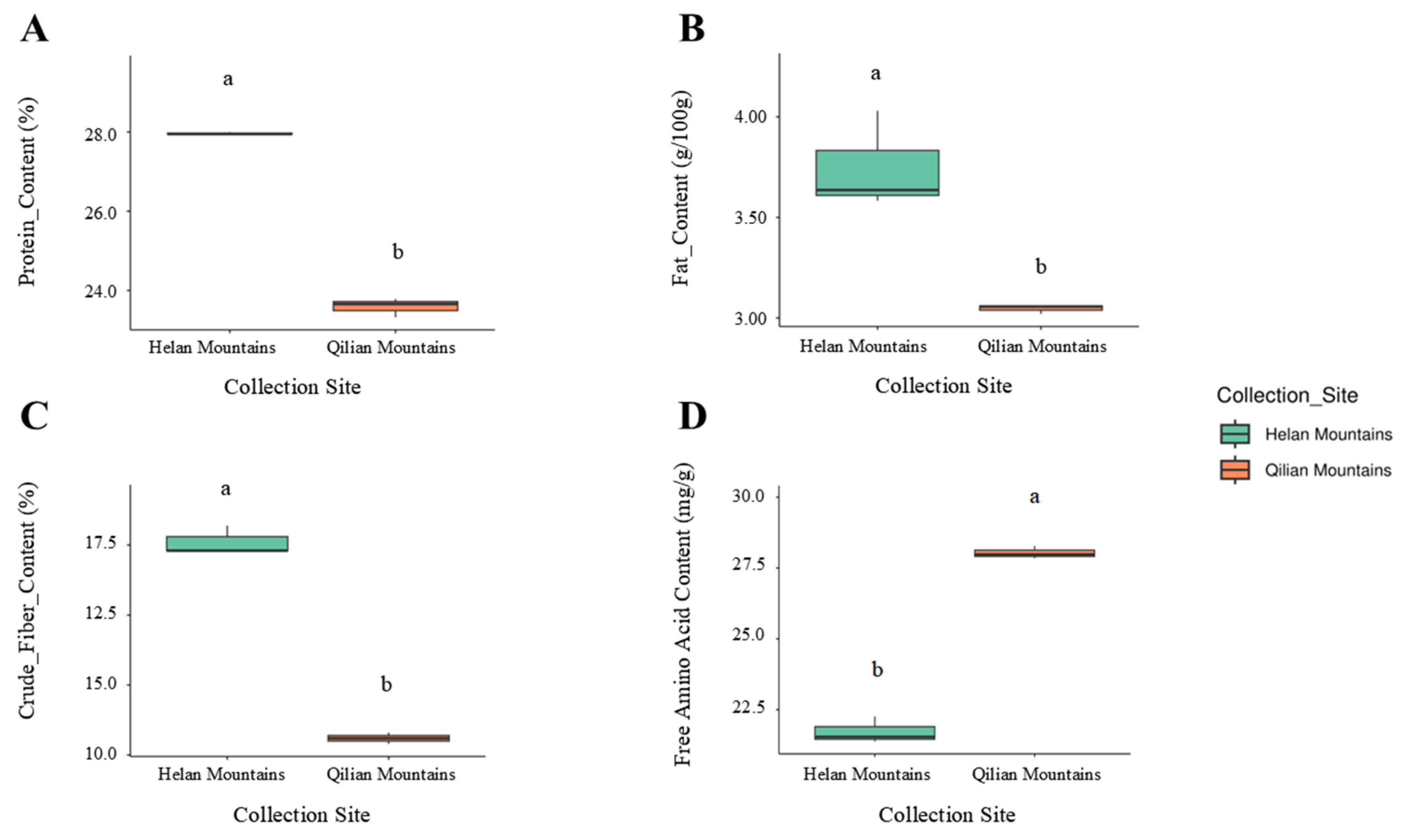

3.2. Contents of Nutrition

3.2.1. Main Nutrients

After testing, the protein content of

C. sinensis in Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain was 27.96 and 23.59 g/100g (dry weight), respectively, with significant difference (p < 0.05) (

Figure 6A). The fat content of the fruitbodies in the two regions was 3.75% and 3.05% (dry weight), respectively, with significant difference (p < 0.05) (

Figure 6B). The crude fiber content of the fruitbodies in the two regions was 17.633 and 10.60 g/100g (dry weight), respectively, with significant difference (p < 0.05) (

Figure 6C). The content of the above three nutrients was higher in the fruitbodies of Helan Mountain. The protein content of the fruitbodies in both regions exceeded 20%, and the content in the fruitbodies of Helan Mountain was close to 30%. The fat content of the fruitbodies in both regions was less than 5%. The crude fiber content of the fruitbodies in both regions was higher than 10%, and the content in the fruitbodies of Helan Mountain was close to 20%. In terms of the content of the above three nutrients, the fruitbodies of

C. sinensis in Helan Mountain are relatively more nutritious.

3.2.2. Free Amino Acid Content and the Effect on Taste

The results of amino acid determination showed that the total free amino acids of

C. sinensis from Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain were significantly different (

Figure 6D). The free amino acids of

C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain was significantly higher than that from Helan Mountain. The content, taste threshold, taste attribute and TAV of

free amino acids were shown in

Table 3. Glu, Thr and Arg were the three amino acids with the highest content, accounting for more than 60% of the total free amino acid content. The difference was that the TAV value of glutamic acid of

C. sinensis from Helan Mountain reached 18.90, which had a significant effect on the flavor taste of fruitbodies. The Glu and Arg values of

C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain were 14.80 and 14.52, respectively, which had significant effects on the flavor and bitter taste of fruitbodies. In addition, the TAV values of His, Val and Lys, which are bad taste amino acids, were higher in

C. sinensis from Qilian Mountain than in that from Helan Mountain.

4. Discussion

4.1. MaxEnt Modeling

In recent years, the MaxEnt model has been increasingly applied in studies such as predicting the potential distribution and adaptability evaluation of rare and endangered species. The analysis of suitable habitat prediction can provide information for exploring the distribution of wild resources of

C. sinensis, and offer a reference for demarcating nature reserves for in - situ protection of

C. sinensis and protecting its wild resources. The MaxEnt model performed excellently in predicting the suitable habitats of

C. sinensis. The average AUC value of the ROC curve for the training set in 10-fold cross-validation was 0.963, with a standard deviation of 0.061. This result indicates that the model has a good fit to the data and a high prediction accuracy. Consistent with numerous published related studies, the MaxEnt model also achieved high AUC values in predicting the distributions of fungi such as

Phellinus spp. [

21] and

Tricholoma matsutake [

5], further confirming its effectiveness and applicability in fungal species distribution research. This model can integrate multiple environmental variables and simulate the relationships between species and the environment through complex algorithms, providing a scientific and reliable technical means for studying the potential distribution of

C. sinensis.

4.2. Main Environmental Variables

Comprehensively considering factors such as Jackknife test, Percent contribution, and Permutation importance, the results show that precipitation has a significant impact on the potential suitable distribution of

C. sinensis. Our model prediction is consistent with the result by Hu et al. [

22]that the occurrence of

C. sinensis is closely related to the rainfall in forest areas. As an ectomycorrhizal fungus, the growth of

C. sinensis is not only related to environmental factors but also closely related to host plants, which is significantly different from saprophytic fungi [

23]. Field surveys have shown that

C. sinensis grows in forests of the genera

Picea and

Larix [

24], especially in

Picea crassifolia forests. This study reports that

C. sinensis mainly grows at an altitude of approximately 2,636 m. This is also consistent with the altitude of

Picea crassifolia distribution in Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain, the main producing areas of

C. sinensis [

25,

26], further testifying to the accuracy and scientific nature of the MaxEnt model prediction results.

The physiological and ecological characteristics of C. sinensis itself also affect its distribution. Its growth has specific requirements for host trees, soil conditions, etc., which limit its survival and reproduction in certain areas. In research and conservation work, it is necessary to comprehensively consider these characteristics to develop more effective conservation measures.

In addition to environmental factors, human interference is also an important factor affecting the distribution of

C. sinensis. Fruitbody hunting of unmatured

C. sinensis results in reducing the resource of

C. sinensis. At the same time, the picking process seriously damages the moss under the

Picea forest, affecting the nutrient structure of the humus layer under the forest and also having a certain impact on the growth of

C. sinensis [

22].

4.3. Distribution and Suitable Habitat Areas

The MaxEnt model prediction shows that the optimal suitable habitats of C. sinensis are mainly concentrated in the Helan Mountain, Qilian Mountain, and other places, including eastern Qinghai, central Gansu, and other regions. There are records of the natural distribution of C. sinensis in these areas, which is consistent with the results of the optimal suitable habitats predicted in this study. The optimal suitable habitats of C. sinensis also appear in Xinjiang (Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture and Turpan City), Tibet(the Xigaze area), and other places where there are no natural distribution records, needs more researches in those areas. Based on the probability of presence, the suitable habitats are divided into different grades, the total areas of highly suitable and optimal suitable habitats is approximately 320,000 square kilometers under the current climate background.

Under future climate scenarios, although the overall distribution pattern of

C. sinensis is similar to the current one, the area will change. The area increases under the SSP1 - 2.6 scenario, while it may increase or decrease under other scenarios compared with the current climate conditions. Under future climate conditions, the contraction area of suitable habitats generally exceeds 150,000 square kilometers, and the expansion area is concentrated and small. The research of Rong et al. [

27] on the suitable area of

Picea crassifolia shows that under future climate scenarios, the suitable area of

Picea crassifolia forest is gradually decreasing. This is consistent with our predicted trend. Although the future climate scenarios we choose are different, this is consistent with the negative impact of global warming on the species distribution range. The centroid of the suitable habitats migrates under different scenarios. As an ectomycorrhizal fungus, the growth of

C. sinensis is closely related to its host. Therefore, when predicting the suitable habitats of

C. sinensis under future climate conditions, it is possible to predict the future distribution of its host, such as

Picea crassifolia, and combine the two for a comprehensive analysis of the suitable habitats.

4.4. Nutritional Components

The nutritional composition of fruitbodies determines their utilization value (Analysis of Nutritional and Functional Components and Antioxidant Activities of Fruitbodies of Seven Edible and Medicinal Fungi). Fruitbodies of

C. sinensis from both study areas are characterized by high protein, low fat, and high crude fiber. These characteristics endow

C. sinensis with healthy advantages such as high nutritional value, being less likely to cause weight gain, and being beneficial for digestion. The protein content of

C. sinensis from both areas exceeds 20%, with that from Helan Mountain approaching 30%; the fat content is less than 5%; and the crude fiber content is higher than 10%, with that from Helan Mountain approaching 20%. However, the contents of crude protein, fat, and crude fiber in the fruitbodies of

C. sinensis from Helan Mountain are significantly higher than those from Qilian Mountain. This difference may be caused by the differences in the physical and chemical properties of the soil in the shady slopes of

Picea crassifolia forests in Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain [

28,

29].

Based on the analysis of free amino acid of C. sinensis from Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain, expecially the TAV values, the reason why C. sinensis from Helan Mountain are more preferable than that from Qilian Mountain could be easily revealled. There is a significant difference in the total amount of free amino acids in the fruitbodies from both areas, and the content of each free amino acid also varies greatly. The TAV values of the off - flavor amino acids His, Val, and Lys in the fruitbodies from Qilian Mountain are higher, and the TAV value of Glu, which can enhance the freshness, is lower compared with that from Helan Mountain, which may be one reason for the relatively poor flavor of the fruitbodies in this area, and could give the support on the dietary preferences for the local consumers in Inner Mongolia.

Most aromatic compounds in food are fat-soluble, and fat acts as a carrier for these flavor substances [

30]. When the fat content is reduced or removed, the perception of taste in the food system will change significantly [

31]. The fat content in the fruitbodies of

C. sinensis in the Qilian Mountains is significantly lower than that in the Helan Mountains, which may be another reason why the taste of

C. sinensis in the Qilian Mountains is relatively less appealing. Meanwhile, as the fat content decreases, the salty, sour, sweet, and bitter tastes in food become more pronounced [

32]. Under the combined influence of lower fat content and higher levels of off-flavor amino acids, the flavor and texture of

C. sinensis in the Qilian Mountains may be inferior to those in the Helan Mountains.

Combing the prediction of geographic distribution and how climate change would affect the geographic range, we proposed in this study that the consume history and dietary preferences should be taken into consideration when formulating protection strategies for edible ectomycorrhizal mushrooms to develop comprehensive conservation strategies in the future.

5. Conclusions

C. sinensis is deeply loved by people in Northwest China due to its unique flavor and nutritional properties. However, under the influence of natural and human factors, its wild resources have sharply declined. In order to further study the current and future distributions of C. sinensis and explore the internal reasons for market demand, we predicted the suitable growth areas of C. sinensis and detected the nutritional components of the fruitbodies collected from the Helan Mountain and Qilian Mountain, which are the main producing areas of C. sinensis. The experimental results show that the suitable growth areas of C. sinensis are mainly concentrated in the adjacent areas at the junctions of Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia and Inner Mongolia. Under future climate conditions, the overall trend of the distribution of suitable growth areas remains unchanged, but the total area shows a downward trend. The determination of nutritional components indicates that the differences in fat content and the contents of flavor - enhancing amino acids may be the reasons why the C. sinensis in the Qilian Mountain tastes inferior to those in the Helan Mountain. Our research provides referable results and new ideas for formulating protection strategies for C. sinensis. However, in this study, the research object, C. sinensis, is an ectomycorrhizal fungus. When predicting its suitable growth areas, we did not consider its host, which may have a certain impact on the accuracy of the prediction of suitable growth areas. At the same time, in the future, it is possible to further detect the contents of different fatty acids in fat to make a more comprehensive judgment on the taste and flavor of the fruitbodies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and J.W.; methodology, Q.L. and J.W.; software, Q.L.; validation, Q.L. and J.W.; formal analysis, Q.L., J.W. and X.L.; investigation, J.W.; resources, L.Y., X.W.; data curation, Q.L. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, Q.L. and J.W.; visualization, Q.L. and X.L.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, Q.L. and J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W., L.Y., X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 32460793), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Alxa League (Project No.: 2020YLAGSC09), and the Platform Construction Project of the Education Department of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, namely "Inner Mongolia Engineering Technology Research of Germplasm Resources Conversation and Utilization" (Project No.: 21400 - 222526).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support for this work from the Innovation Team of Inner Mongolia University

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liimatainen, K.; Kim, J.T.; Pokorny, L.; Kirk, P.M.; Dentinger, B.; Niskanen, T. Taming the Beast: A Revised Classification of Cortinariaceae Based on Genomic Data. Fungal Divers. 2022, 112, 89–170. [CrossRef]

- Dai X.; Du F.; Liang Y.; Zhu X. Scientific Name Recognition of Helanshan Zimogu. Edible Fungi China 2022, 41, 7–10. [CrossRef]

- Xie M. Taxonomic, Molecular Phylogenetic and Biogeographic Studies of Cortinarius in China. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Normal University: Changchun, Jilin, China, 2022.

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum Entropy Modeling of Species Geographic Distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, H.; Gao, B.; Gu, W. Prediction of the Potential Geographic Distribution of the Ectomycorrhizal Mushroom Tricholoma Matsutake under Multiple Climate Change Scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46221. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bao, Q.; Bao, Y.; Wei, J. Prediction of Potential Suitable Distribution of <italic>Leucocalocybe Mongolica</Italic> Based on MaxEnt Model. Mycosystema 2023, 42, 2141–2151. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Niyati, N.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Chinese Caterpillar Fungus (Ophiocordyceps Sinensis) in China: Current Distribution, Trading, and Futures under Climate Change and Overexploitation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142548. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-S. Fungal Diversity Notes 1277–1386: Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Contributions to Fungal Taxa. Fungal Divers. 2020.

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very High Resolution Interpolated Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Zhao, L.; Tan, G.-R.; Shen, X.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Li, Q.-Q.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of Multidimensional Simulations of Summer Air Temperature in China from CMIP5 to CMIP6 by the BCC Models: From Trends to Modes. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 28–41. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yu, R.; Lu, Y.; Jie, W.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xin, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. BCC-CSM2-HR: A High-Resolution Version of the Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 2977–3006. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Xin, X. Short Commentary on CMIP6 Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP). Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2019, 15, 519. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Kong, Z. Simulation and Analysis of Red-Crowned Crane Habitat Suitability Using Maximum Entropy and Information Entropy Models. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110999. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Ferrier, S. An Evaluation of Alternative Algorithms for Fitting Species Distribution Models Using Logistic Regression. Ecol. Model. 2000, 128, 127–147. [CrossRef]

- Wang R.; Wang M.; Luo J.; Liu Y.; Wu S.; Wen G.; Li Q. The Analysis of Climate Suitability and Regionalization of Actinidia deliciosa by Using MaxEnt Model in China. J. YUNNAN Agric. Univ. Sci. 2019, 34, 522–531.

- Duan, H.; Xia, S.; Hou, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X. Conservation Planning Following Reclamation of Intertidal Areas throughout the Yellow and Bohai Seas, China. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 3787–3801. [CrossRef]

- Vollering, J.; Halvorsen, R.; Auestad, I.; Rydgren, K. Bunching up the Background Betters Bias in Species Distribution Models. ECOGRAPHY 2019, 42, 1717–1727. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudik, M.; Schapire, R.E.; Blair, M.E. Opening the Black Box: An Open-Source Release of Maxent. ECOGRAPHY 2017, 40, 887–893. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-W.; Zhang, M. Non-Volatile Taste Active Compounds in the Meat of Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir Sinensis). Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1200–1205. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Su, J.; Liu, X.; Yan, D.; Lin, Y. Taste Evaluation of Non-Volatile Taste Compounds in Bivalve Mollusks from Beibu Gluf, Guangxi. Food Sci. 2012, 33, 165–168.

- Yuan, H.-S.; Wei, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-G. Maxent Modeling for Predicting the Potential Distribution of Sanghuang, an Important Group of Medicinal Fungi in China. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 140–145. [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Su, Y. Current Situation of Cortinarius Sp. Resources in Helan Mountain and Protection Countermeasures. J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 90–93.

- Hall, I.R.; Yun, W.; Amicucci, A. Cultivation of Edible Ectomycorrhizal Mushrooms. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 433–438. [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wei, T.; Ji, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Research Progress on Taxonomy System and Species Diversity of Cortinarius. J. Fungal Res. 2023, 21, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, F.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qi, W. Omni-Directional Distribution Patterns of Montane Coniferous Forest in the Helan Mountains of China. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 724–733. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Webb, A.A.; Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, S.; Yu, P. Influence of Climatic and Geographic Factors on the Spatial Distribution of Qinghai Spruce Forests in the Dryland Qilian Mountains of Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 1007–1017. [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Zhao, C.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zang, F.; Guo, Z.; Mao, Y.; Wang, L. Modeling the Effect of Climate Change on the Potential Distribution of Qinghai Spruce (Picea Crassifolia Kom.) in Qilian Mountains. Forests 2019, 10, 62. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B. The relationships between carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus in plants, soil nutrients and slope in different forest types in the Helan Mountains. Shengtaixue Zazhi 2024, 43, 3324–3332. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lei, L.; Liu, X.; Jin, M.; Zhang, X.; Jing, W. Soil Physicochemical Properties of Picea Crassifolia Forest in Eastern Qilian Mountains. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2011, 31, 72–75. [CrossRef]

- Yackinous, C.; Guinard, J.-X. Flavor Manipulation Can Enhance the Impression of Fat in Some Foods. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 909–914. [CrossRef]

- Carrapiso, A.I. Effect of Fat Content on Flavour Release from Sausages. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 396–403. [CrossRef]

- Tingting, M.; Xing, Z.; Zhenyou, L.U.; Buji, W.E.I.; Hanfeng, Z.O.U.; Liuxiang, Q.I.N.; Li, L.U.; Bingyan, P.A.N. Reviews of Effects of Fat on the Flavor and System Stability of Low-Fat Plant Protein Beverage. Food Mach. 2019, 35, 220–225. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).