Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Geometric Means of Physical Quantities and Constants of Nature

- (a)

- The speed of light c imposed by the vacuum is the G-M average of the reciprocals of the vacuum permittivity and the vacuum permeability , viz.whereas the other G-M defines the impedance of free space .

- (b)

- (c)

- Because of equation (2), the Compton length is also the G-M of the three well-known atomic length scales, viz.

1.2. The Well-Known Long-Range Conservative Forces

1.3. Setbacks Preventing Progress Toward Force Unification

- (a)

- The field constants G and K have been disregarded or summarily dismissed precisely because they do not vary. We bring them back and follow them closely in this work.

- (b)

- The gravitational and Coulomb forces have been considered together in relativistic spacetimes (e.g., Refs. [17,18,19]), but these descriptions do not capture the notion of a combined conservative field generated by mass and charge and acting on to masses and/or charges. Specifically, such combinations of forces are incapable of describing the forcing of masses by charges and vice versa. We endeavor to remedy the situation in this work.

- (c)

-

The current descriptions of the physical principles at their most basic level are not uniformly understood, and this precludes a concise account of certain fundamental concepts, as they apply to different contexts [2,3]. For instance:

- (i)

- It is not clear across realms that the vacuum’s resistive constants (permittivity), (permeability), and (impedance) are always imprinted by the vacuum with a geometric factor of that is characteristic of free 3D space. For instance, there is not a single equation of physics in which is not divided by [20], yet the 3D geometric imprint was entirely ignored and alone was declared to be the actual universal constant dictated by the vacuum.

- (ii)

- It is certainly not appreciated that Dirac’s constant [21,22] can only describe effects in 2D spaces (because of the attached factor), and its ad hoc implementation into the fine-structure constant and other intrinsically 3D physical constants has destroyed their underlying 3D geometries, rendering such constants unusable and/or misleading. In our treatments, we use Planck’s constant h to define such 3D constants (e.g., in equation (3)) with immediate results that clearly make physical sense [1,2,3].

- (iii)

-

Certain relationships between fundamental constants have remained undetected until recently [3]:

- ①

- The ohmic resistance in the Planck system of units, viz. , is precisely equal to the impedance of free space (properly imprinted by the 3D geometric factor of ).

- ②

- The weak coupling constant of electroweak theory is equal to , where the fine-structure constant is defined in terms of Planck’s h, as in equation (3).

- ③

- ④

- For completeness, the above numerical concurrence can be extended to also include Coulomb’s constant K and the speed of light c, viz.

- ⑤

- ⑥

- Remarkably, the square root of also has another meaning: the numerical value of C [6] is clearly related to the value of the Boltzmann constant which, in turn, appears in the definition of the entropy of an ideal gas of temperature T [29]. We have determined that , when is expressed in MeV [6] (that is, ), and that when is expressed in the SI unit of MJ .

- ⑦

- The above G-M (or ) that appears in the metric system is highly unusual and warrants further investigation. To our knowledge, this is the first ever occurrence in physics where multiplies (or, equivalently, Coulomb’s constant K divides ). For this reason, we are not surprised that the numerical value (i.e., the SI ‘strength’) of this G-M appears also as a scale in another physical context (the Boltzmann entropy of states in classical thermodynamics [29,30]).

1.4. Outline

2. Cross-Forcing by Masses on to Charges and by Charges on to Masses

2.1. Dimensional Analysis of Cross-Forces

2.2. The Equations of the Two Conservative Cross-Forces

2.3. The G-M Constant

2.4. The Sources of the Cross-Field

3. Constants of Nature Produced by G-M Averaging of Known Constants

3.1. The Geometric Means of G and

3.2. The Geometric Means of and

3.2.1. The G-M Constant

- (a)

- The attractive Newtonian force between two masses separated by distance r has the same magnitude as the repulsive Coulomb force between two electrons or protons at the same distance r, viz.

- (b)

- The repulsive cross-force of mass on to an electron at distance r (or the attractive reaction force on to ) has the same magnitude as the repulsive Coulomb force between two electrons or protons at distance r, viz.

- (a)

- First, is scaled down to the much smaller (subatomic) mass MeV/ [2] by the dimensionless constant , where the normalized gravitational constant [3] is given byand it represents the ratio of the gravitational to the electrostatic energy between two electrons separated by any distance r. The numerical value of was obtained from the new value of Newton’s G (equation (15)) and the CODATA values of e and [6], and it is precise to 10 significant digits.

- (b)

- Second, equation (25) indicates that is also scaled down to by . Mass was first obtained in Ref. [2] from an altogether different perspective, and it was expressed in atomic units (GeV/). The argument was that, if the gravitational coupling constant is running at higher energies, then meets the fine-structure constant (i.e., ) at the critical mass GeV/. Thus, the critical mass may also be determined from equation (26) by letting and .

3.2.2. The G-M Constant

- “When a numerological formula is proposed, then we may ask whether it is correct. The notion of exact correctness has a clear meaning when the formula is purely mathematical, but otherwise some clarification is required. I think an appropriate definition of correctness is that the formula has a good explanation, in a Platonic sense, that is, the explanation could be based on a good theory that is not yet known but ‘exists’ in the universe of possible reasonable ideas.”

3.3. The G-M That Produces the Weak Coupling Constant and the Second G-M

3.3.1. The Weak Coupling Constant as a G-M

3.3.2. The Second G-M and Associated Planck Units

3.3.3. Distinguished Electromagnetic Planck Units

- (a)

-

The unit of capacitance is , where is a scaling coefficient of the G-M. Substituting from equation (39), we find for the Planck capacitance the equivalent relationThis relation should be compared to the Schwarzschild-like equation in the Planck system of units, and these two equations also imply that .

- (b)

- The unit of magnetic flux is , where is a scaling coefficient of the G-M, which also represents the Planck unit of electric resistance . We have previously identified with the impedance of free space properly imprinted by the 3D geometric term of , viz. [3]. Thus, the unit of magnetic flux can cast in the simple form

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- An investigation of cross-forces in a combined gravitational and electrostatic field yields physically understood results. The new coupling constant that also balances the units in the equations of these cross-forces is the G-M of the known constants G (Newton’s constant) and K (Coulomb’s constant). Thus, there is no need to introduce yet another independent constant to describe cross-interactions between masses and charges and vice versa (Section 2).

- (2)

- G-M averaging is pervasive in nature and in physics. Nature uses G-Ms in abundance to generate new universal constants, and physicists have used G-Ms (heretofore unknowingly) to define many (if not all) physical variables conveniently used in our explorations of the contents of the universe (Section 1 and Section 3).

- (3)

- By delineating nature’s G-Ms, we get a bird’s eye view at her mathematical prowess [1,2,3,9]. More than that, we have discovered that nature uses the same numerical values (‘strengths’) in what we perceive as disjoint physical contexts (Section 3 and Ref. [3]). In retrospect, how could nature have possibly done otherwise? Different numbers exist to describe differing strengths of various agents (and physical thresholds), but each agent should consistently exert the same level of strength across different settings in the same system of units and measurements. In this respect, the SI system of units is self-consistent (unlike the cgs system), as it does not reset the values of various physical constants for the sake of convenience.

- (4)

- Application of the same numerical value in different settings has led us to derive the following equivalent strengths of universal constants irrespective of their units in the metric (SI) system: MOND critical acceleration with ; MOND universal constant with ; effective gravitational constant with . Furthermore, several physically important G-Ms of natural constants were found to be related to Planck units (Section 3.2 and Section 3.3).

- (5)

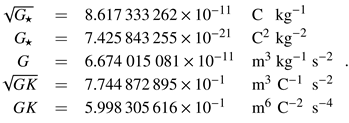

- The above numerical equivalence of to a submultiple of allows for the determination of several fundamental constants to an unprecedented precision of 10 significant digits:

- (6)

- We have shown that using ℏ in physics begs for insurmountable trouble. The composite constant that presently is carries an imprint of 2D geometry (), which is inappropriate in 3D settings and damages all man-made definitions that use ℏ in various physical settings (e.g., the fine-structure constant and the gravitational coupling constant, but not their very useful ratio (equation (26)) in which ℏ fortuitously cancels out). Thus, the important relations concerning G-Ms that we have described in this work do not present themselves in the contemporary equations of physics written in terms of ℏ.

- (7)

- Some equations in which appears have previously issued a fair warning that no-one noticed. In this context where the 3D constant appears self-consistently, we mentioned the examples of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and the ring singularity in the Kerr-Newman metric (see bottom of Section 3.2.2).

- (8)

- Reverting back to Planck’s h yields immediately spectacular results: the electroweak theory needs only one fundamental constant, the fine-structure constant , since the weak coupling constant is simply equal to (see top of Section 3). Experimenters who measure these constants individually by various methods should take notice.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CODATA | Committee On Data |

| G-M | Geometric Mean |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| MOND | Modified Newtonian Dynamics |

| PDG | Particle Data Group |

| SI | Système International d’unités |

References

- Christodoulou, D. M., & Kazanas, D. 2023, Varying-G gravity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 519, 1277.

- Christodoulou, D. M., & Kazanas, D. 2023, The upgraded Planck system of units that reaches from the known Planck scale all the way down to subatomic scales. Astronomy, 2, 235. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, D. M., & Kazanas, D. 2025, Introducing the effective gravitational constant 4πε0G. Axioms, 00, 00.

- Lie, S. 1881, On integration of a class of linear partial differential equations by means of definite integrals. Archiv. Math. Nat., 6, 328.

- Abramowitz, M., & Stegun, I. A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1972, p. 10, item 3.1.6.

- Tiesinga, E., Mohr, P. J., Newell, D. B., & Taylor, B. N. 2021, CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018. Rev. Mod. Phys., 93, 025010. [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. 1899, About irreversible radiation processes. Sitzungsberichte Der Preuss. Akad. Wiss., 440.

- Planck, M. 1900, Ueber irreversible Strahlungsvorgänge. Ann. Phys., 4, S.69.

- Christodoulou, D. M., O’Leary, J., Melatos, A., Kimpson, T., Bhattacharya, S., Laycock, S. G. T. O’Neill, N. J., Meyers, P. M., & Kazanas, D. 2025, Magellanic accretion-powered pulsars studied via an unscented Kalman filter. Astrophys. J., 00, 00.

- Melatos, A., O’Neill, N. J., Meyers, P. M., & O’Leary, J. 2023, Tracking hidden magnetospheric fluctuations in accretion-powered pulsars with a Kalman filter. Astrophys. J., 944, 64. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, J., Melatos, A., O’Neill, N. J., et al. 2024, Measuring the magnetic dipole moment and magnetospheric fluctuations of SXP 18.3 with a Kalman filter. Astrophys. J., 965, 102. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, J., Melatos, A., Kimpson, T., et al. 2024, Measuring the magnetic dipole moment and magnetospheric fluctuations of accretion-powered pulsars in the Small Magellanic Cloud with an unscented Kalman filter. Astrophys. J., 971, 126. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, J., Melatos, A., Kimpson, T., et al. 2025, Observing Rayleigh-Taylor stable and unstable accretion through a Kalman filter analysis of X-ray pulsars in the Small Magellanic Cloud. Astrophys. J., 981, 150. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. 1907, Über das Relativitätsprinzip und die aus demselben gezogenen folgerungen. Jahrbuch der Radioaktivität und Elektronik, 4, 411.

- Einstein, A. 1925, Einheitliche Feldtheorie von Gravitation und Elektrizität. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vol. 1, 414.

- Paulson, S., Gleiser, M., Freese, K., & Tegmark, M. 2015, The unification of physics: the quest for a theory of everything. Ann. NY Acad. Sci., 1361, 18. [CrossRef]

- Misner, C. W., Thorne, K. S., & Wheeler, J. A. Gravitation. W. H. Freeman & Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973.

- Mannheim, P. D., & Kazanas, D. 1991, Solutions to the Reissner-Nordström, Kerr, and Kerr-Newman problems in fourth-order conformal Weyl gravity. Phys. Rev. D, 44, 417. [CrossRef]

- Bakopoulos, A., & Kanti, P. 2014, From GEM to electromagnetism. Gen. Relativ. Grav., 46, 1742. [CrossRef]

- Balanis, C. A. Antenna theory. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005.

- Dirac, P. A. M. 1926, On the theory of quantum mechanics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, 112, 661.

- Dirac, P. A. M. 1928, The quantum theory of the electron. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, 117, 610.

- Milgrom, M. 1983a, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophys. J., 270, 365. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. 1983b, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics – Implications for galaxies. Astrophys. J., 270, 371.

- Milgrom, M. 1983c, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics: Implications for galaxy systems. Astrophys. J., 270, 384.

- Famaey, B., & McGaugh, S. S. 2012, Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND): Observational phenomenology and relativistic extensions. Living Rev. Rel., 15, 10. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. 2014, MOND laws of galactic dynamics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 437, 2531. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. 2015, MOND theory. Can. J. Phys., 93, 107.

- Boltzmann, L. Vorlesungen über gastheorie. Part 1, J. A. Barth: Leipzig, Germany, 1896.

- Planck, M. Vorlesungen über die theorie der wärmestrahlung. J. A. Barth: Leipzig, Germany, 1913.

- Zyla, P. A., et al (Particle Data Group) 2020, Review of particle physics. Prog Theor Exp Phys, 2020(8), 083C01.

- Workman, R. L., Burkert, V. D., Crede, V., et al. [Particle Data Group] 2022, Review of particle physics. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys., 2022(8), 083C01.

- Navas, S., Amsler, C., Gutsche, T. et al. [Particle Data Group] 2024, Review of particle physics. Phys. Rev. D, 110, 030001.

- Wikipedia 2025a, Reissner-Nordström metric. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reissner%E2%80%93Nordstr%C3%B6m_metric (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Wikipedia 2025b, Black hole electron. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_hole_electron (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Good, I. J. A quantal hypothesis for hadrons and the judging of physical numerology. In G. R. Grimmett and D. J. A. Welsh (eds.) Disorder in Physical Systems. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990, p. 141.

- Kazanas, D., Papadopoulos, D., & Christodoulou, D. M. 2022, Gravity beyond Einstein? Yes, but in which direction? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 380, 20210367. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia 2025c, Uncertainty principle. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_principle (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Wikipedia 2025d, Kerr-Newman metric. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerr%E2%80%93Newman_metric (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Elert, G. 2025, The physics hypertextbook. URL: https://physics.info/planck/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Wikipedia 2025e, Planck units. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planck_units (accessed on 18 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).